Intracerebral hemorrhage

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cerebral haemorrhage, cerebral hemorrhage, intra-axial hemorrhage, cerebral hematoma, cerebral bleed, brain bleed, hemorrhagic stroke |

| |

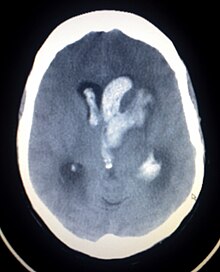

| CT scanof a spontaneous intracerebral bleed, leaking into thelateral ventricles | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery |

| Symptoms | Headache,one-sided numbness, weakness, tingling, or paralysis, speech problems, vision or hearing problems, dizziness or lightheadedness or vertigo, nausea/vomiting, seizures,decreased levelortotal loss of consciousness,neck stiffness,memory loss, attention and coordination problems, balance problems,fever,shortness of breath(when bleed is in the brain stem)[1][2] |

| Complications | Coma,persistent vegetative state,cardiac arrest(when bleeding is severe or in the brain stem),death |

| Causes | Brain trauma,aneurysms,arteriovenous malformations,brain tumors,hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic stroke[1] |

| Risk factors | High blood pressure,diabetes,high cholesterol,amyloidosis,alcoholism,low cholesterol,blood thinners,cocaineuse[2] |

| Diagnostic method | CT scan[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Ischemic stroke[1] |

| Treatment | Blood pressurecontrol, surgery,ventricular drain[1] |

| Prognosis | 20% good outcome[2] |

| Frequency | 2.5 per 10,000 people a year[2] |

| Deaths | 44% die within one month[2] |

Intracerebral hemorrhage(ICH), also known ashemorrhagic stroke,is a sudden bleeding intothe tissues of the brain(i.e. the parenchyma), into itsventricles,or into both.[3][4][1]An ICH is a type of bleeding within theskulland one kind ofstroke(ischemic stroke being the other).[3][4]Symptoms can vary dramatically depending on the severity (how much blood), acuity (over what timeframe), and location (anatomically) but can includeheadache,one-sided weakness,numbness, tingling, orparalysis,speech problems, vision or hearing problems, memory loss, attention problems, coordination problems, balance problems,dizzinessorlightheadednessorvertigo,nausea/vomiting, seizures,decreased level of consciousnessortotal loss of consciousness,neck stiffness,andfever.[2][1]

Hemorrhagic stroke may occur on the background of alterations to the blood vessels in the brain, such as cerebralarteriolosclerosis,cerebral amyloid angiopathy,cerebral arteriovenous malformation,brain trauma,brain tumorsand anintracranial aneurysm,which can cause intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage.[1]

The biggest risk factors for spontaneous bleeding arehigh blood pressureandamyloidosis.[2]Other risk factors includealcoholism,low cholesterol,blood thinners,andcocaineuse.[2]Diagnosis is typically byCT scan.[1]

Treatment should typically be carried out in anintensive care unitdue to strict blood pressure goals and frequent use of both pressors and antihypertensive agents.[1][5]Anticoagulationshould be reversed if possible andblood sugarkept in the normal range.[1]A procedure to place anexternal ventricular drainmay be used to treathydrocephalusor increasedintracranial pressure,however, the use ofcorticosteroidsis frequently avoided.[1]Sometimes surgery to directly remove the blood can be therapeutic.[1]

Cerebral bleeding affects about 2.5 per 10,000 people each year.[2]It occurs more often in males and older people.[2]About 44% of those affected die within a month.[2]A good outcome occurs in about 20% of those affected.[2]Intracerebral hemorrhage, a type of hemorrhagic stroke, was first distinguished from ischemic strokes due to insufficient blood flow, so called "leaks and plugs", in 1823.[6]

Epidemiology[edit]

The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage is estimated at 24.6 cases per 100,000 person years with the incidence rate being similar in men and women.[7][8]The incidence is much higher in the elderly, especially those who are 85 or older, who are 9.6 times more likely to have an intracerebral hemorrhage as compared to those of middle age.[8]It accounts for 20% of all cases ofcerebrovascular diseasein the United States, behindcerebral thrombosis(40%) andcerebral embolism(30%).[9]

Types[edit]

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage[edit]

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage(IPH) is one form ofintracerebral bleedingin which there is bleeding within brainparenchyma.[10]Intraparenchymal hemorrhage accounts for approximately 8-13% of allstrokesand results from a wide spectrum of disorders. It is more likely to result indeathor majordisabilitythanischemic strokeorsubarachnoid hemorrhage,and therefore constitutes an immediatemedical emergency.Intracerebral hemorrhages and accompanyingedemamay disrupt or compress adjacentbrain tissue,leading to neurological dysfunction. Substantial displacement of brain parenchyma may cause elevation ofintracranial pressure(ICP) and potentially fatalherniation syndromes.

Intraventricular hemorrhage[edit]

Intraventricular hemorrhage(IVH), also known asintraventricular bleeding, is ableedinginto the brain'sventricular system,where thecerebrospinal fluidis produced and circulates through towards thesubarachnoid space.It can result fromphysical traumaor fromhemorrhagic stroke.

30% of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) are primary, confined to the ventricular system and typically caused by intraventricular trauma, aneurysm, vascular malformations, or tumors, particularly of the choroid plexus.[11]However 70% of IVH are secondary in nature, resulting from an expansion of an existing intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage.[11]Intraventricular hemorrhage has been found to occur in 35% of moderate to severetraumatic brain injuries.[12]Thus the hemorrhage usually does not occur without extensive associated damage, and so the outcome is rarely good.[13][14]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

People with intracerebral bleeding have symptoms that correspond to the functions controlled by the area of the brain that is damaged by the bleed.[15]These localizing signs and symptoms can includehemiplegia(or weakness localized to one side of the body) and paresthesia (loss of sensation) including hemisensory loss (if localized to one side of the body).[7]These symptoms are usually rapid in onset, sometimes occurring in minutes, but not as rapid as the symptom onset inischemic stroke.[7]While the duration of onset not be as rapid, it is important that patients go to the emergency department as soon as they notice any symptoms as early detection and management of stroke may lead to better outcomes post-stroke than delayed identification.[16]

A mnemonic to remember the warning signs of stroke isFAST(facial droop, arm weakness, speech difficulty, and time to call emergency services),[17]as advocated by theDepartment of Health (United Kingdom)and theStroke Association,theAmerican Stroke Association,theNational Stroke Association(US), theLos Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)[18]and theCincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale(CPSS).[19]Use of these scales is recommended by professional guidelines.[20]FAST is less reliable in the recognition of posterior circulation stroke.[21]

Other symptoms include those that indicate a rise inintracranial pressurecaused by a large mass (due to hematoma expansion) putting pressure on the brain.[15]These symptoms includeheadaches,nausea, vomiting, a depressed level of consciousness, stupor and death.[7]Continued elevation in the intracranial pressure and the accompanying mass effect may eventually causebrain herniation(when different parts of the brain are displaced or shifted to new areas in relation to the skull and surroundingdura matersupporting structures). Brain herniation is associated withhyperventilation,extensor rigidity,pupillary asymmetry,pyramidal signs,comaand death.[10]

Hemorrhage into thebasal gangliaorthalamuscauses contralateral hemiplegia due to damage to theinternal capsule.[7]Other possible symptoms includegaze palsiesor hemisensory loss.[7]Intracerebral hemorrhage into thecerebellummay causeataxia,vertigo,incoordination of limbs and vomiting.[7]Some cases of cerebellar hemorrhage lead to blockage of thefourth ventriclewith subsequent impairment of drainage ofcerebrospinal fluidfrom the brain.[7]The ensuinghydrocephalus,or fluid buildup in theventriclesof the brain leads to a decreased level of consciousness,total loss of consciousness,coma,andpersistent vegetative state.[7]Brainstem hemorrhage most commonly occurs in theponsand is associated withshortness of breath,cranial nerve palsies,pinpoint (but reactive) pupils, gaze palsies, facial weakness,coma,andpersistent vegetative state(if there is damage to thereticular activating system).[7]

Causes[edit]

Intracerebral bleeds are the second most common cause ofstroke,accounting for 10% of hospital admissions for stroke.[23]High blood pressureraises the risks of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage by two to six times.[22]More common in adults than in children, intraparenchymal bleeds are usually due topenetrating head trauma,but can also be due to depressedskull fractures.Acceleration-deceleration trauma,[24][25][26]rupture of ananeurysmorarteriovenous malformation(AVM), and bleeding within atumorare additional causes.Amyloid angiopathyis not an uncommon cause of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients over the age of 55. A very small proportion is due tocerebral venous sinus thrombosis.[citation needed]

Risk factors for ICH include:[11]

- Hypertension(high blood pressure)

- Diabetes mellitus

- Menopause

- Excessivealcohol consumption

- Severemigraine

Hypertension is the strongest risk factor associated with intracerebral hemorrhage and long term control of elevated blood pressure has been shown to reduce the incidence of hemorrhage.[7]Cerebral amyloid angiopathy,a disease characterized by deposition ofamyloid betapeptides in the walls of the small blood vessels of the brain, leading to weakened blood vessel walls and an increased risk of bleeding; is also an important risk factor for the development of intracerebral hemorrhage. Other risk factors include advancing age (usually with a concomitant increase of cerebral amyloid angiopathy risk in the elderly), use ofanticoagulantsorantiplatelet medications,the presence of cerebral microbleeds,chronic kidney disease,and lowlow density lipoprotein(LDL) levels (usually below 70).[27][28]The direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) such as thefactor Xa inhibitorsordirect thrombin inhibitorsare thought to have a lower risk of intracerebral hemorrhage as compared to thevitamin K antagonistssuch aswarfarin.[7]

Cigarette smokingmay be a risk factor but the association is weak.[29]

Traumautic intracerebral hematomas are divided into acute and delayed. Acute intracerebral hematomas occur at the time of the injury while delayed intracerebral hematomas have been reported from as early as 6 hours post injury to as long as several weeks.[citation needed]

Diagnosis[edit]

Bothcomputed tomography angiography(CTA) andmagnetic resonance angiography(MRA) have been proved to be effective in diagnosing intracranial vascular malformations after ICH.[12]So frequently, a CT angiogram will be performed in order to exclude a secondary cause of hemorrhage[30]or to detect a "spot sign".

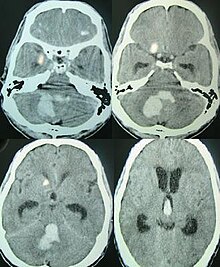

Intraparenchymal hemorrhagecan be recognized onCT scansbecause blood appears brighter than other tissue and is separated from the inner table of the skull by brain tissue. The tissue surrounding a bleed is often less dense than the rest of the brain because ofedema,and therefore shows up darker on the CT scan.[30]The oedema surrounding the haemorrhage would rapidly increase in size in the first 48 hours, and reached its maximum extent at day 14. The bigger the size of the haematoma, the larger its surrounding oedema.[31]Brain oedema formation is due to the breakdown of red blood cells, where haemoglobin and other contents of red blood cells are released. The release of these red blood cells contents causes toxic effect on the brain and causes brain oedema. Besides, the breaking down of blood-brain barrier also contributes to the odema formation.[13]

Apart from CT scans, haematoma progression of intracerebral haemorrhage can be monitored using transcranial ultrasound. Ultrasound probe can be placed at the temporal lobe to estimate the volume of haematoma within the brain, thus identifying those with active bleeding for further intervention to stop the bleeding. Using ultrasound can also reduces radiation risk to the subject from CT scans.[14]

Location[edit]

When due tohigh blood pressure,intracerebral hemorrhages typically occur in theputamen(50%) orthalamus(15%), cerebrum (10–20%), cerebellum (10–13%), pons (7–15%), or elsewhere in the brainstem (1–6%).[32][33]

Treatment[edit]

Treatment depends substantially on the type of ICH. RapidCT scanand other diagnostic measures are used to determine proper treatment, which may include both medication and surgery.

- Tracheal intubationis indicated in people with decreased level of consciousness or other risk of airway obstruction.[34]

- IV fluidsare given to maintainfluid balance,using isotonic rather than hypotonic fluids.[34]

Medications[edit]

Rapid lowering of the blood pressure usingantihypertensive therapyfor those withhypertensive emergencycan have higher functional recovery at 90 days post intracerebral haemorrhage, when compared to those who undergone other treatments such as mannitol administration, reversal of anticoagulation (those previously on anticoagulant treatment for other conditions), surgery to evacuate the haematoma, and standard rehabilitation care in hospital, while showing similar rate of death at 12%.[35]Early lowering of the blood pressure can reduce the volume of the haematoma, but may not have any effect against the oedema surrounding the haematoma.[36]Reducing the blood pressure rapidly does not causebrain ischemiain those who have intracerebral haemorrhage.[37]TheAmerican Heart AssociationandAmerican Stroke Associationguidelines in 2015 recommended decreasing the blood pressure to a SBP of 140 mmHg.[1]However, later reviews found unclear difference between intensive and less intensive blood pressure control.[38][39]

GivingFactor VIIawithin 4 hours limits the bleeding and formation of ahematoma.However, it also increases the risk ofthromboembolism.[34]It thus overall does not result in better outcomes in those without hemophilia.[40]

Frozen plasma,vitamin K,protamine,orplatelet transfusionsmay be given in case of acoagulopathy.[34]Platelets however appear to worsen outcomes in those with spontaneous intracerebral bleeding on antiplatelet medication.[41]

The specific reversal agentsidarucizumabandandexanet alfamay be used to stop continued intracerebral hemorrhage in people taking directly oral acting anticoagulants (such as factor Xa inhibitors or direct thrombin inhibitors).[7]However, if these specialized medications are not available,prothrombin complex concentratemay also be used.[7]

Only 7% of those with ICH are presented with clinical features of seizures while up to 25% of those have subclinical seizures. Seizures are not associated with an increased risk of death or disability. Meanwhile, anticonvulsant administration can increase the risk of death. Therefore, anticonvulsants are only reserved for those that have shown obvious clinical features of seizures or seizure activity onelectroencephalography(EEG).[42]

H2 antagonists or proton pump inhibitors are commonly given to try to preventstress ulcers,a condition linked with ICH.[34]

Corticosteroidswere thought to reduce swelling. However, in large controlled studies, corticosteroids have been found to increase mortality rates and are no longer recommended.[43][44]

Surgery[edit]

Surgery is required if thehematomais greater than 3 cm (1 in), if there is a structuralvascularlesionorlobarhemorrhagein a young patient.[34]

Acathetermay be passed into the brainvasculatureto close off or dilateblood vessels,avoiding invasive surgical procedures.[45]

Aspiration bystereotactic surgeryorendoscopicdrainage may be used inbasal gangliahemorrhages, although successful reports are limited.[34]

Acraniectomyholds promise of reduced mortality, but the effects of long‐term neurological outcome remain controversial.[46]

Prognosis[edit]

About 8 to 33% of those with intracranial haemorrhage have neurological deterioration within the first 24 hours of hospital admission, where a large proportion of them happens within 6 to 12 hours. Rate of haematoma expansion, perihaematoma odema volume and the presence of fever can affect the chances of getting neurological complications.[47]

The risk of death from an intraparenchymal bleed in traumatic brain injury is especially high when the injury occurs in thebrain stem.[48]Intraparenchymal bleeds within themedulla oblongataare almost always fatal, because they cause damage to cranial nerve X, thevagus nerve,which plays an important role inblood circulationand breathing.[24]This kind of hemorrhage can also occur in thecortexor subcortical areas, usually in thefrontalortemporal lobeswhen due to head injury, and sometimes in thecerebellum.[24][49]Larger volumes of hematoma at hospital admission as well as greater expansion of the hematoma on subsequent evaluation (usually occurring within 6 hours of symptom onset) are associated with a worse prognosis.[7][50]Perihematomal edema, or secondary edema surrounding the hematoma, is associated with secondary brain injury, worsening neurological function and is associated with poor outcomes.[7]Intraventricular hemorrhage, or bleeding into the ventricles of the brain, which may occur in 30–50% of patients, is also associated with long-term disability and a poor prognosis.[7]Brain herniation is associated with poor prognoses.[7]

For spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage seen on CT scan, the death rate (mortality) is 34–50% by 30 days after the injury,[22]and half of the deaths occur in the first 2 days.[51]Even though the majority of deaths occur in the first few days after ICH, survivors have a long-term excess mortality rate of 27% compared to the general population.[52]Of those who survive an intracerebral hemorrhage, 12–39% are independent with regard to self-care; others are disabled to varying degrees and require supportive care.[8]

References[edit]

- ^abcdefghijklmnHemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, Becker K, Bendok BR, Cushman M, et al. (Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing) (July 2015)."Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association".Stroke.46(7): 2032–2060.doi:10.1161/str.0000000000000069.PMID26022637.

- ^abcdefghijklCaceres JA, Goldstein JN (August 2012)."Intracranial hemorrhage".Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America.30(3): 771–794.doi:10.1016/j.emc.2012.06.003.PMC3443867.PMID22974648.

- ^ab"Brain Bleed/Hemorrhage (Intracranial Hemorrhage): Causes, Symptoms, Treatment".

- ^abNaidich TP, Castillo M, Cha S, Smirniotopoulos JG (2012).Imaging of the Brain, Expert Radiology Series,1: Imaging of the Brain.Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 387.ISBN978-1416050094.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-10-02.

- ^Ko SB, Yoon BW (December 2017)."Blood Pressure Management for Acute Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke: The Evidence".Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.38(6): 718–725.doi:10.1055/s-0037-1608777.PMID29262429.

- ^Hennerici M (2003).Imaging in Stroke.Remedica. p. 1.ISBN9781901346251.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-10-02.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrSheth KN (October 2022). "Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage".The New England Journal of Medicine.387(17): 1589–1596.doi:10.1056/NEJMra2201449.PMID36300975.S2CID253159180.

- ^abcvan Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ (February 2010). "Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis".The Lancet. Neurology.9(2): 167–176.doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70340-0.PMID20056489.S2CID25364307.

- ^Page 117 in:Schutta HS, Lechtenberg R (1998).Neurology practice guidelines.New York: M. Dekker.ISBN978-0-8247-0104-8.

- ^abKalita J, Misra UK, Vajpeyee A, Phadke RV, Handique A, Salwani V (April 2009)."Brain herniations in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage".Acta Neurologica Scandinavica.119(4): 254–260.doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01095.x.PMID19053952.S2CID21870062.

- ^abcFeldmann E, Broderick JP, Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, Brott T, et al. (September 2005)."Major risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage in the young are modifiable".Stroke.36(9): 1881–1885.doi:10.1161/01.str.0000177480.62341.6b.PMID16081867.

- ^abJosephson CB, White PM, Krishan A, Al-Shahi Salman R (September 2014)."Computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography for detection of intracranial vascular malformations in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2014(9): CD009372.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009372.pub2.PMC6544803.PMID25177839.

- ^abXi G, Hua Y, Bhasin RR, Ennis SR, Keep RF, Hoff JT (December 2001). "Mechanisms of edema formation after intracerebral hemorrhage: effects of extravasated red blood cells on blood flow and blood-brain barrier integrity".Stroke.32(12): 2932–2938.doi:10.1161/hs1201.099820.PMID11739998.S2CID7089563.

- ^abOvesen C, Christensen AF, Krieger DW, Rosenbaum S, Havsteen I, Christensen H (April 2014)."Time course of early postadmission hematoma expansion in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage".Stroke.45(4): 994–999.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003608.PMID24627116.S2CID7716659.

- ^abVinas FC, Pilitsis J (2006)."Penetrating Head Trauma".Emedicine.com.Archived fromthe originalon 2005-09-13.

- ^Colton K, Richards CT, Pruitt PB, Mendelson SJ, Holl JL, Naidech AM, et al. (February 2020)."Early Stroke Recognition and Time-based Emergency Care Performance Metrics for Intracerebral Hemorrhage".Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases.29(2): 104552.doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.104552.PMC6954314.PMID31839545.

- ^Harbison J, Massey A, Barnett L, Hodge D, Ford GA (June 1999). "Rapid ambulance protocol for acute stroke".Lancet.353(9168): 1935.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00966-6.PMID10371574.S2CID36692451.

- ^Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Schubert GB, Eckstein M, Starkman S (January 1998). "Design and retrospective analysis of the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)".Prehospital Emergency Care.2(4): 267–273.doi:10.1080/10903129808958878.PMID9799012.

- ^Kothari RU, Pancioli A, Liu T, Brott T, Broderick J (April 1999). "Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: reproducibility and validity".Annals of Emergency Medicine.33(4): 373–378.doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70299-4.PMID10092713.

- ^Meredith TL, Freed N, Soulsby C, Bay S (2009)."Clinical audit to assess implications of implementing National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline 32: Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at Barts and the London National Health Service (NHS) Trust 2007".Proceedings of the Nutrition Society.68(OCE1).doi:10.1017/s0029665109002080.ISSN0029-6651.

- ^Merwick Á, Werring D (May 2014)."Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke".BMJ.348(may19 33): g3175.doi:10.1136/bmj.g3175.PMID24842277.

- ^abcdYadav YR, Mukerji G, Shenoy R, Basoor A, Jain G, Nelson A (January 2007)."Endoscopic management of hypertensive intraventricular haemorrhage with obstructive hydrocephalus".BMC Neurology.7:1.doi:10.1186/1471-2377-7-1.PMC1780056.PMID17204141.

- ^Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. (January 2013)."Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association".Circulation.127(1): e6–e245.doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad.PMC5408511.PMID23239837.

- ^abcMcCaffrey P (2001)."CMSD 336 Neuropathologies of Language and Cognition".The Neuroscience on the Web Series.Chico: California State University. Archived fromthe originalon 2005-11-25.Retrieved19 June2007.

- ^"Overview of Adult Traumatic Brain Injuries"(PDF).Orlando Regional Healthcare, Education and Development.2004. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2008-02-27.Retrieved2008-01-16.

- ^Shepherd S (2004)."Head Trauma".Emedicine.com.Archived fromthe originalon 2005-10-26.Retrieved19 June2007.

- ^Ma C, Gurol ME, Huang Z, Lichtenstein AH, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. (July 2019)."Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of intracerebral hemorrhage: A prospective study".Neurology.93(5): e445–e457.doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007853.PMC6693427.PMID31266905.

- ^An SJ, Kim TJ, Yoon BW (January 2017)."Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Clinical Features of Intracerebral Hemorrhage: An Update".Journal of Stroke.19(1): 3–10.doi:10.5853/jos.2016.00864.PMC5307940.PMID28178408.

- ^Carhuapoma JR,Mayer SA,Hanley DF (2009).Intracerebral Hemorrhage.Cambridge University Press. p. 6.ISBN978-0-521-87331-4.

- ^abYeung R, Ahmad T, Aviv RI, de Tilly LN, Fox AJ, Symons SP (March 2009)."Comparison of CTA to DSA in determining the etiology of spontaneous ICH".The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques.36(2): 176–180.doi:10.1017/s0317167100006533.PMID19378710.

- ^Venkatasubramanian C, Mlynash M, Finley-Caulfield A, Eyngorn I, Kalimuthu R, Snider RW, Wijman CA (January 2011)."Natural history of perihematomal edema after intracerebral hemorrhage measured by serial magnetic resonance imaging".Stroke.42(1): 73–80.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.590646.PMC3074599.PMID21164136.

- ^Greenberg MS (2016).Handbook of Neurosurgery.Thieme.ISBN9781626232419.

- ^Prayson RA (2012).Neuropathology.Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 49.ISBN978-1437709490.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-03-12.

- ^abcdefgLiebeskind DS (7 August 2006)."Intracranial Haemorrhage: Treatment & Medication".eMedicine Specialties > Neurology > Neurological Emergencies.Archived fromthe originalon 2009-03-12.

- ^Anderson CS, Qureshi AI (January 2015)."Implications of INTERACT2 and other clinical trials: blood pressure management in acute intracerebral hemorrhage".Stroke.46(1): 291–295.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006321.PMID25395408.S2CID45730236.

- ^Anderson CS, Huang Y, Arima H, Heeley E, Skulina C, Parsons MW, et al. (February 2010)."Effects of early intensive blood pressure-lowering treatment on the growth of hematoma and perihematomal edema in acute intracerebral hemorrhage: the Intensive Blood Pressure Reduction in Acute Cerebral Haemorrhage Trial (INTERACT)".Stroke.41(2): 307–312.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561795.PMID20044534.S2CID5871420.

- ^Butcher KS, Jeerakathil T, Hill M, Demchuk AM, Dowlatshahi D, Coutts SB, et al. (March 2013)."The Intracerebral Hemorrhage Acutely Decreasing Arterial Pressure Trial".Stroke.44(3): 620–626.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000188.PMID23391776.S2CID54488358.

- ^Ma J, Li H, Liu Y, You C, Huang S, Ma L (2015). "Effects of Intensive Blood Pressure Lowering on Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials".Turkish Neurosurgery.25(4): 544–551.doi:10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.9270-13.0(inactive 31 January 2024).PMID26242330.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^Boulouis G, Morotti A, Goldstein JN, Charidimou A (April 2017). "Intensive blood pressure lowering in patients with acute intracerebral haemorrhage: clinical outcomes and haemorrhage expansion. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials".Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry.88(4): 339–345.doi:10.1136/jnnp-2016-315346.PMID28214798.S2CID25397701.

- ^Yuan ZH, Jiang JK, Huang WD, Pan J, Zhu JY, Wang JZ (June 2010). "A meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage without hemophilia".Journal of Clinical Neuroscience.17(6): 685–693.doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2009.11.020.PMID20399668.S2CID30590573.

- ^Eilertsen H, Menon CS, Law ZK, Chen C, Bath PM, Steiner T, Desborough M Jr, Sandset EC, Sprigg N, Al-Shahi Salman R (2023-10-23)."Haemostatic therapies for stroke due to acute, spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2023(10): CD005951.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005951.pub5.ISSN1469-493X.PMC10591281.PMID37870112.

- ^Fogarty Mack P (December 2014)."Intracranial haemorrhage: therapeutic interventions and anaesthetic management".British Journal of Anaesthesia.113(Suppl 2): ii17–ii25.doi:10.1093/bja/aeu397.PMID25498578.

- ^Roberts I, Yates D, Sandercock P, Farrell B, Wasserberg J, Lomas G, et al. (9 October 2016). "Effect of intravenous corticosteroids on death within 14 days in 10008 adults with clinically significant head injury (MRC CRASH trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial".Lancet.364(9442): 1321–1328.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17188-2.PMID15474134.S2CID30210176.

- ^Edwards P, Arango M, Balica L, Cottingham R, El-Sayed H, Farrell B, et al. (2005). "Final results of MRC CRASH, a randomised placebo-controlled trial of intravenous corticosteroid in adults with head injury-outcomes at 6 months".Lancet.365(9475): 1957–1959.doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66552-x.PMID15936423.S2CID27713031.

- ^"Cerebral Hemorrhages".Cedars-Sinai Health System.Archived fromthe originalon 2009-03-12.Retrieved25 February2009.

- ^Sahuquillo J, Dennis JA (December 2019)."Decompressive craniectomy for the treatment of high intracranial pressure in closed traumatic brain injury".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2019(12): CD003983.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003983.pub3.PMC6953357.PMID31887790.

- ^Lord AS, Gilmore E, Choi HA, Mayer SA (March 2015)."Time course and predictors of neurological deterioration after intracerebral hemorrhage".Stroke.46(3): 647–652.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007704.PMC4739782.PMID25657190.

- ^Sanders MJ, McKenna K (2001). "Chapter 22: Head and Facial Trauma".Mosby's Paramedic Textbook(2nd revised ed.). Mosby.

- ^Graham DI, Gennareli TA (2000). "Chapter 5". In Cooper P, Golfinos G (eds.).Pathology of Brain Damage After Head Injury(4th ed.). New York: Morgan Hill.

- ^Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Huster G (July 1993)."Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage. A powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality".Stroke.24(7): 987–993.doi:10.1161/01.STR.24.7.987.PMID8322400.S2CID3107793.

- ^Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, Hanley D, Kase C, Krieger D, et al. (June 2007)."Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in adults: 2007 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, High Blood Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group".Stroke.38(6): 2001–2023.doi:10.1161/strokeaha.107.183689.PMID17478736.

- ^Hansen BM, Nilsson OG, Anderson H, Norrving B, Säveland H, Lindgren A (October 2013)."Long term (13 years) prognosis after primary intracerebral haemorrhage: a prospective population based study of long term mortality, prognostic factors and causes of death".Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry.84(10): 1150–1155.doi:10.1136/jnnp-2013-305200.PMID23715913.S2CID40379279.Archivedfrom the original on 2014-02-22.