Intrusive rock

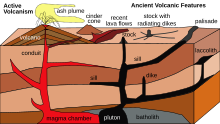

Intrusive rockis formed whenmagmapenetrates existing rock, crystallizes, and solidifies underground to formintrusions,such asbatholiths,dikes,sills,laccoliths,andvolcanic necks.[1][2][3]

Intrusion is one of the two waysigneous rockcan form. The other isextrusion,such as avolcanic eruptionor similar event. An intrusion is any body of intrusive igneous rock, formed from magma that cools and solidifies within the crust of theplanet.In contrast, anextrusionconsists of extrusive rock, formed above the surface of the crust.

Some geologists use the termplutonic rocksynonymously with intrusive rock, but other geologists subdivide intrusive rock, by crystal size, into coarse-grained plutonic rock (typically formed deeper in theEarth's crustin batholiths orstocks) and medium-grainedsubvolcanic or hypabyssal rock(typically formed higher in the crust in dikes and sills).[4]

Classification[edit]

Because the solidcountry rockinto which magma intrudes is an excellent insulator, cooling of the magma is extremely slow, and intrusive igneous rock is coarse-grained (phaneritic). However, the rate of cooling is greatest for intrusions at relatively shallow depth, and the rock in such intrusions is often much less coarse-grained than intrusive rock formed at greater depth. Coarse-grained intrusive igneous rocks that form at depth within the Earth are calledabyssalorplutonicwhile those that form near the surface are calledsubvolcanicorhypabyssal.[4]

Plutonic rocks are classified separately from extrusive igneous rocks, generally on the basis of theirmineralcontent. The relative amounts ofquartz,alkali feldspar,plagioclase,andfeldspathoidare particularly important in classifying intrusive igneous rocks, and most plutonic rocks are classified by where they fall in theQAPF diagram.Dioriticandgabbroicrocks are further distinguished by whether the plagioclase they contain issodium-rich, and sodium-poor gabbros are classified by their relative contents of variousiron- ormagnesium-rich minerals (maficminerals) such asolivine,hornblende,clinopyroxene,and orthopyroxene, which are the most common mafic minerals in intrusive rock. Rareultramafic rocks,which contain more than 90% mafic minerals, andcarbonatiterocks, containing over 50% carbonate minerals, have their own special classifications.[5][6]

Hypabyssal rocks resemble volcanic rocks more than they resemble plutonic rocks, being nearly as fine-grained, and are usually assigned volcanic rock names. However,dikesofbasalticcomposition often show grain sizes intermediate between plutonic and volcanic rock, and are classified asdiabasesor dolerites. Rare ultramafic hypabyssal rocks calledlamprophyreshave their own classification scheme.[7]

Characteristics[edit]

Intrusive rocks are characterized by largecrystalsizes, and as the individual crystals are visible, the rock is calledphaneritic.[8]There are few indications of flow in intrusive rocks, since their texture and structure mostly develops in the final stages of crystallization, when flow has ended.[9]Contained gases cannot escape through the overlying strata, and these gases sometimes formcavities,often lined with large, well-shaped crystals. These are particularly common in granites and their presence is described asmiarolitic texture.[10]Because their crystals are of roughly equal size, intrusive rocks are said to beequigranular.[11]

Plutonic rocks are less likely than volcanic rocks to show a pronouncedporphyritictexture, in which a first generation of large well-shaped crystals are embedded in a fine-grained ground-mass. The minerals of each have formed in a definite order, and each has had a period of crystallization that may be very distinct or may have coincided with or overlapped the period of formation of some of the other ingredients. Earlier crystals originated at a time when most of the rock was still liquid and are more or less perfect. Later crystals are less regular in shape because they were compelled to occupy the spaces left between the already-formed crystals. The former case is said to beidiomorphic(orautomorphic); the latter isxenomorphic.

There are also many other characteristics that serve to distinguish plutonic from volcanic rock. For example, the alkali feldspar in plutonic rocks is typicallyorthoclase,while the higher-temperature polymorph,sanidine,is more common in volcanic rock. The same distinction holds fornephelinevarieties.Leuciteis common in lavas but very rare in plutonic rocks.Muscoviteis confined to intrusions. These differences show the influence of the physical conditions under which crystallization takes place.[12]

Hypabyssal rocks show structures intermediate between those ofextrusiveand plutonic rocks. They are very commonly porphyritic,vitreous,and sometimes evenvesicular.In fact, many of them arepetrologicallyindistinguishable from lavas of similar composition.[12][7]

Occurrences[edit]

Plutonic rocks form 7% of the Earth's current land surface.[13]Intrusions vary widely, from mountain-range-sizedbatholithsto thinveinlikefracturefillings ofapliteorpegmatite.

- Batholith:a large irregular discordant intrusion

- Chonolith:an irregularly-shaped intrusion with a demonstrable base

- Cupola:a dome-shaped projection from the top of a large subterranean intrusion

- Dike:a relatively narrow tabular discordant body, often nearly vertical

- Laccolith:concordant body with roughly flat base andconvextop, usually with a feeder pipe below

- Lopolith:concordant body with roughly flat top and a shallow convex base, may have a feeder dike or pipe below

- Phacolith:a concordant lens-shaped pluton that typically occupies the crest of ananticlineor trough of asyncline

- Volcanic pipeorvolcanic neck:tubular, roughly vertical body that may have been a feeder vent for avolcano

- Sill:a relatively thin tabular concordant body intruded along bedding planes

- Stock:a smaller irregular discordant intrusive

- Boss: a small stock

See also[edit]

- Ellicott City Granodiorite

- Guilford Quartz Monzonite

- Pluton emplacement

- Norbeck Intrusive Suite

- Subvolcanic rock

- Tuolumne Intrusive Suite

- Volcanic rock

- Woodstock Quartz Monzonite

References[edit]

- ^Intrusive Rocks:Intrusive rocks,accessdate: March 27, 2017.

- ^Igneous intrusive rocks:Igneous intrusive rocksArchived2018-05-12 at theWayback Machine,accessdate: March 27, 2017.

- ^Britannica.com:intrusive rock | geology | Britannica.com,accessdate: March 27, 2017.

- ^abPhilpotts, Anthony R.; Ague, Jay J. (2009).Principles of igneous and metamorphic petrology(2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 52.ISBN9780521880060.

- ^Le Bas, M. J.; Streckeisen, A. L. (1991). "The IUGS systematics of igneous rocks".Journal of the Geological Society.148(5): 825–833.Bibcode:1991JGSoc.148..825L.CiteSeerX10.1.1.692.4446.doi:10.1144/gsjgs.148.5.0825.S2CID28548230.

- ^"Rock Classification Scheme - Vol 1 - Igneous"(PDF).British Geological Survey: Rock Classification Scheme.1:1–52. 1999.

- ^abPhilpotts & Ague 2009,p. 139.

- ^Blatt, Harvey; Tracy, Robert J. (1996).Petrology: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic(2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. 12–13.ISBN0716724383.

- ^Philpotts & Ague 2009,p. 48.

- ^Blatt & Tracy 1996,p. 44.

- ^rocks and minerals:Geology - rocks and minerals,accessdate: March 28, 2017.

- ^abOne or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in thepublic domain:Flett, John Smith (1911). "Petrology".InChisholm, Hugh(ed.).Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 327.

- ^Wilkinson, Bruce H.; McElroy, Brandon J.; Kesler, Stephen E.; Peters, Shanan E.; Rothman, Edward D. (2008). "Global geologic maps are tectonic speedometers—Rates of rock cycling from area-age frequencies".Geological Society of America Bulletin.121(5–6): 760–779.doi:10.1130/B26457.1.