James Bond (literary character)

| James Bond | |

|---|---|

| James Bondcharacter | |

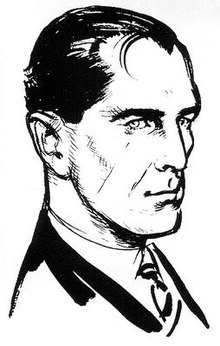

Ian Fleming's image of James Bond; commissioned to aid theDaily Expresscomic strip artists. | |

| First appearance | Casino Royale(1953) |

| Created by | Ian Fleming |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | 007 |

| Gender | Male |

| Title | Commander(Royal Naval Reserve) |

| Occupation | Intelligence agent |

| Family | Andrew Bond (father) Monique Delacroix Bond (mother) |

| Spouse | Teresa di Vicenzo(widowed) |

| Significantother | Kissy Suzuki |

| Children | James Suzuki |

| Relatives | Charmian Bond (aunt) Max Bond (uncle) James Bond Jr.(nephew) |

| Nationality | British |

CommanderJames BondCMGRNVRis a character created by the British journalist and novelistIan Flemingin 1953. He is theprotagonistof theJames Bondseries ofnovels,films,comicsandvideo games.Fleming wrote twelve Bond novels and two short story collections. His final two books—The Man with the Golden Gun(1965) andOctopussy and The Living Daylights(1966)—were published posthumously.

The character is aSecret Serviceofficer, code number007(pronounced "double-O[/oʊ/]-seven "), residing in London but active internationally. Bond was a composite character who was based on a number ofcommandoswhom Fleming knew during his service in theNaval Intelligence Divisionduring theSecond World War,to whom Fleming added his own style and a number of his own tastes. Bond's name may have been appropriated from theAmerican ornithologist of the same name,although it is possible that Fleming took the name from a Welsh agent with whom he served, James C. Bond. Bond has a number of consistent character traits which run throughout the books, including an enjoyment of cars, a love of food, drink and sex, and an average intake of sixty custom-made cigarettes a day.

Since Fleming's death in 1964, there have been other authorised writers of Bond material, includingJohn Gardner,who wrote fourteen novels and two novelizations;Raymond Benson,who wrote six novels, three novelizations and three short stories; andAnthony Horowitz,who has written three novels. There have also been other authors who wrote one book each:Kingsley Amis(under the pseudonym Robert Markham),Sebastian Faulks,Jeffery DeaverandWilliam Boyd.Additionally, a series of novels based on Bond's youth—Young Bond—was written byCharlie Higsonand laterStephen Cole.

As aspin-offfrom the original literary work,Casino Royale,a television adaptation was made, "Casino Royale",in which Bond was depicted as an American agent. Acomic stripseries also ran in theDaily Expressnewspaper. There have been twenty-seven Bond films;seven actors have played Bond in the films.

Background and inspiration[edit]

The central figure in Ian Fleming's work is the fictional character of James Bond, anintelligence officerin the "Secret Service".Bond is also known by his code number, 007, and was aRoyal Naval ReserveCommander.

James Bond is the culmination of an important but much-maligned tradition in English literature. As a boy, Fleming devoured theBulldog Drummondtales of Lieutenant ColonelHerman Cyril McNeile(aka "Sapper" ) and theRichard Hannaystories ofJohn Buchan.His genius was to repackage these antiquated adventures to fit the fashion of postwar Britain... In Bond, he created a Bulldog Drummond for thejet age.

William Cook in theNew Statesman[1]

During theSecond World War,Ian Fleming had mentioned to friends that he wanted to write a spy novel.[2]It was not until 1952, however, shortly before his wedding to his pregnant girlfriend,Ann Charteris,that Fleming began to write his first book,Casino Royale,to distract himself from his forthcoming nuptials.[3]Fleming started writing the novel at hisGoldeneye estatein Jamaica on 17 February 1952, typing out 2,000 words in the morning, directly from his own experiences and imagination.[4]He finished work on the manuscript in just over a month,[5]completing it on 18 March 1952.[6]Describing the work as his "dreadful oafish opus",[7]Fleming showed it to an ex-girlfriend, Clare Blanchard, who advised him not to publish it at all, but that if he did so, it should be under another name.[8]Despite that advice, Fleming went on to write a total of twelve Bond novels and two short story collections before his death on 12 August 1964.[9]The last two books—The Man with the Golden GunandOctopussy and The Living Daylights—were published posthumously.[10]

Inspiration for the character[edit]

Fleming based his creation on a number of individuals which he came across during his time in theNaval Intelligence Divisionduring the Second World War, admitting that Bond "was a compound of all the secret agents and commando types I met during the war".[11]Among those types were his brother,Peter,whom Fleming worshipped[11]and who had been involved in behind-the-lines operations in Norway and Greece during the war.[12]

Aside from Fleming's brother, a number of others also provided some aspects of Bond's make up, includingConrad O'Brien-ffrench,a skiing spy whom Fleming had met inKitzbühelin the 1930s,Patrick Dalzel-Job,who served with distinction in30 AUduring the war, andBill "Biffy" Dunderdale,station head of MI6 in Paris, who wore cuff-links and handmade suits and was chauffeured around Paris in aRolls-Royce.[11][13]Sir Fitzroy Macleanwas another figure mentioned as a possibility, based on his wartime work behind enemy lines in theBalkans,as was the MI6double agentDušan Popov.[14]

In 2016, aBBC Radio 4documentary explored the possibility that the character of Bond was created by 20th Century author and mentor to Fleming,Phyllis Bottomein her 1946 novel,The Lifeline.Distinct similarities between the protagonist inThe Lifeline,Mark Chalmers, and Bond have been highlighted by spy writerNigel West.[15]

Origins of the name[edit]

Fleming took the name for his character from that of the AmericanornithologistJames Bond,aCaribbeanbird expert and author of the definitivefield guideBirds of the West Indies;Fleming, a keenbirdwatcherhimself, had a copy of Bond's guide and he later explained to the ornithologist's wife that "It struck me that this brief, unromantic, Anglo-Saxon and yet very masculine name was just what I needed, and so a second James Bond was born".[16]

When I wrote the first one in 1953, I wanted Bond to be an extremely dull, uninteresting man to whom things happened; I wanted him to be a blunt instrument... when I was casting around for a name for my protagonist I thought by God, [James Bond] is the dullest name I ever heard.

Ian Fleming,The New Yorker,21 April 1962[17]

On another occasion Fleming said: "I wanted the simplest, dullest, plainest-sounding name I could find, 'James Bond' was much better than something more interesting, like 'Peregrine Carruthers'. Exotic things would happen to and around him, but he would be a neutral figure—an anonymous, blunt instrument wielded by a government department."[18]After Fleming met the ornithologist and his wife, he described them as "a charming couple who are amused by the whole joke".[19]In the first draft ofCasino Royalehe decided to use the name James Secretan as Bond's cover name while on missions.[20]

In 2018, it was reported that the name could have emerged from a former member of theSpecial Operations Executive,James Charles Bond, who had, according to released military records, served under Fleming.[21][22]

Bond's code number—007—was assigned by Fleming in reference to one of British naval intelligence's key achievements ofFirst World War:the breaking of the German diplomatic code.[23]One of the German documents cracked and read by the British was theZimmermann Telegram,which was coded 0075,[24]and which was one of the factors that led to the US entering the war.

Characterisation[edit]

Appearance[edit]

Facially, Bond resembles the composer, singer and actorHoagy Carmichael.InCasino Royale,Vesper Lyndremarks, "Bond reminds me rather of Hoagy Carmichael, but there is something cold and ruthless." Likewise, inMoonraker,Special BranchOfficerGala Brandthinks that Bond is "certainly good-looking... Rather like Hoagy Carmichael in a way. That black hair falling down over the right eyebrow. Much the same bones. But there was something a bit cruel in the mouth, and the eyes were cold."[25]Others, such as journalistBen Macintyre,identify aspects of Fleming's own looks in his description of Bond.[26]General references in the novels describe Bond as having "dark, rather cruel good looks".[27]

In the novels (notablyFrom Russia, with Love), Bond's physical description has generally been consistent: slim build; a 3 in (76 mm) long, thin vertical scar on his right cheek; blue-grey eyes; a "cruel" mouth; short, black hair, a comma of which rests on his forehead. Physically he is described as 1.83 m (6 ft 0 in) in height and 76 kg (168 lb) in weight.[27]DuringCasino Royale,a SMERSH agent carves the RussianCyrillicletter "Ш" (SH) (forShpion:"Spy" ) into the back of Bond's right hand; by the start ofLive and Let Die,Bond has had askin graftto hide the scars.[28]

Background[edit]

Early life[edit]

In Fleming's stories, Bond is in his mid-to-late thirties, but does not age.[29]InMoonraker,he admits to being eight years shy of mandatory retirement age from the 00 section—45—which would mean he was 37 at the time.[30]Fleming did not provide Bond's date of birth, butJohn Pearson's fictional biography of Bond,James Bond: The Authorized Biography of 007,gives him a birth date of 11 November 1920,[31]while a study by Bond scholar John Griswold puts the date at 11 November 1921.[32]According to Griswold, the Fleming novels take place between around May 1951,[33]to February 1964, by which time Bond was aged 42.[34]

If the quality of these books, or their degree of veracity, had been any higher, the author would certainly have been prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act. It is a measure of the disdain in which these fictions are held at the Ministry, that action has not yet—I emphasize the qualification—been taken against the author and publisher of these high-flown and romanticized caricatures of episodes in the career of an outstanding public servant.

You Only Live Twice,Chapter 21: Obit:[35]

Fleming wroteOn Her Majesty's Secret ServicewhileDr. Nowas being filmed in Jamaica and was influenced by the casting of Scottish actorSean Conneryto give Bond Scottish ancestry.[36]It was not until the penultimate novel,You Only Live Twice,that Fleming gave Bond a more complete sense of family background, using a fictional obituary, purportedly fromThe Times.[37]The novel reveals Bond’s parents were Andrew Bond, ofGlencoe,and Monique Delacroix, of theCanton de Vaud.[38]The book was the first to be written after the release ofDr. Noin cinemas and Connery's depiction of Bond affected Fleming's interpretation of the character, to give Bond a sense of humour that was not present in the previous stories.[39]Bond spends much of his early life abroad, becoming multilingual in German and French because of his father's work as aVickersarmaments company representative. Bond is orphaned at age 11 after his parents are killed in amountain climbingaccident in theAiguilles RougesnearChamonix.[40]

After the death of his parents, Bond went to live with his aunt, Miss Charmian Bond, in the village ofPett Bottom,where he completed his early education. Later, he briefly attendedEton Collegeat "12 or thereabouts", but was expelled after twohalvesbecause of girl trouble with a maid.[37]After being sent down from Eton, Bond was sent toFettes Collegein Scotland, his father's school.[38]On his first visit toParisat the age of 16, Bond lost hisvirginity,later reminiscing about the event in "From a View to a Kill".[41]Fleming referenced his own upbringing for his creation, with Bond alluding to briefly attending theUniversity of Geneva[42](as did Fleming), before being taught to ski inKitzbühel(as was Fleming) by Hannes Oberhauser, who is later killed in "Octopussy".[43][41]

Bond joined theSecret Servicein 1938–as described by a Russian dossier about him inFrom Russia, with Love.[33]He spent two months in 1939 at theMonte Carlo Casinowatching a Romanian group cheating before he and theDeuxième Bureauclosed them down.[43]Bond's obituary inYou Only Live Twicestates that he joined "a branch of what was subsequently to become theMinistry of Defence"in 1941, where he rose to the rank of principal officer.[44][38]The same year he became alieutenantin theRoyal Naval Volunteer Reserve,ending the war as a commander.[43]

At the start of Fleming's first book,Casino Royale,Bond is already a 00 agent, having been given the position after killing two enemy agents, a Japanese spy on the thirty-sixth floor of theRCA BuildingatRockefeller Center(then housing the headquarters ofBritish Security Co-ordination– BSC) in New York City and aNorwegiandouble agent who had betrayed two British agents; it is suggested by Bond scholar John Griswold that these were part of Bond's wartime service withSpecial Operations Executive,a British Second World War covert military organisation.[45]Bond is made aCompanion of the Order of St Michael and St Georgein either 1953–as described by a Russian dossier about Bond inFrom Russia, with Love—or 1954, as described by Bond's obituary inYou Only Live Twice.[46]

Personal life[edit]

Bond lives in a flat off theKing's RoadinChelsea.Continuation authorsJohn PearsonandWilliam Boydboth identify the location as Wellington Square. The former believed the address was No. 30, and the latter No. 25.[47]His flat is looked after by an elderly Scottish housekeeper namedMay.May's name was taken from May Maxwell, the housekeeper of Fleming's close friend, the American Ivar Bryce.[48]In 1955 Bond earned around £2,000 a yearnet(equivalent to £66,000 in 2023); although when on assignment, he worked on an unlimited expense account.[49]Much of Fleming's own daily routine while working atThe Sunday Timeswas woven into the Bond stories,[50]and he summarised it at the beginning ofMoonraker:

... elastic office hours from around ten to six; lunch, generally in the canteen; evenings spent playing cards in the company of a few close friends, or atCrockford's;or making love, with rather cold passion, to one of three similarly disposed married women; weekends playing golf for high stakes at one of the clubs near London.

Moonraker,Chapter 1: Secret paper-work[51]

Only once in the series does Fleming have a partner for Bond in his flat, with the arrival ofTiffany Case,following Bond's mission to the US inDiamonds Are Forever.By the start of the following book,From Russia, With Love,Case has left to marry an American.[49]Bond is married only once, inOn Her Majesty's Secret Service,toTeresa "Tracy" di Vicenzo,but their marriage ends tragically when she is killed on their wedding day by Bond'snemesisErnst Stavro Blofeld.[52]

In the penultimate novel of the series,You Only Live Twice,Bond suffers fromamnesiaand has a relationship with anAmadiving girl,Kissy Suzuki.As a result of the relationship, Kissy becomes pregnant, although she does not reveal this to Bond before he leaves the island.[53]

Tastes and style[edit]

Drinks[edit]

Fleming biographerAndrew Lycettnoted that, "within the first few pages [ofCasino Royale] Ian had introduced most of Bond's idiosyncrasies and trademarks ", which included his looks, his Bentley and his smoking and drinking habits.[54]The full details of Bond'smartiniwere kept until chapter seven of the book and Bond eventually named it "The Vesper",after his love interestVesper Lynd.

'A dry martini,' he said. 'One. In a deepchampagne goblet.'

'Oui, monsieur.'

'Just a moment. Three measures ofGordon's,one ofvodka,half a measure ofKina Lillet.Shake it very well until it's ice-cold, then add a large thin slice oflemon peel.Got it?'

'Certainly monsieur.' The barman seemed pleased with the idea.

'Gosh, that's certainly a drink,' said Leiter.

Bond laughed. 'When I'm... er... concentrating,' he explained, 'I never have more than one drink before dinner. But I do like that one to be large and very strong and very cold, and very well-made. I hate small portions of anything, particularly when they taste bad. This drink's my own invention. I'm going to patent it when I think of a good name.'

Casino Royale,Chapter 7: Rouge et Noir[55]

Bond's drinking habits run throughout the series of books. During the course ofOn Her Majesty's Secret Servicealone, Bond consumes forty-six drinks:Pouilly-Fuissé,RiquewihrandMarsalawines, most of a bottle of Algerian wine, some 1953Château Mouton Rothschildclaret,along withTaittingerandKrugchampagnes andBabycham;for whiskies he consumes threebourbonand waters, half a pint of I.W. Harper bourbon,Jack Daniel'swhiskey, two double bourbons on the rocks, two whisky and sodas, two neat scotches and one glass of neat whisky; vodka consumption totalled four vodka and tonics and three double vodka martinis; other spirits included two double brandies with ginger ale, a flask ofEnzian schnapsand a double gin: he also washes this down with four steins of German beer.[56][57]Bond's alcohol intake does not seem to affect his performance.[58]

Regarding non-alcoholic drinks, Bond eschews tea, calling it "mud" and blaming it for the downfall of theBritish Empire.He instead prefers to drink strong coffee.[59]

Food[edit]

When in England and not on a mission, Bond dines as simply as Fleming did on dishes such as grilled sole,oeufs en cocotteand coldroast beefwithpotato salad.[60]When on a mission, however, Bond eats more extravagantly.[61]This was partly because in 1953, whenCasino Royalewas published, many items of food were still rationed in the UK,[1]and Bond was "the ideal antidote to Britain's postwar austerity, rationing and the looming premonition of lost power".[62]This extravagance was more noteworthy with his contemporary readers for Bond eating exotic, local foods when abroad,[63]at a time when most of his readership did not travel abroad.[64]

On 1 April 1958 Fleming wrote toThe Manchester Guardianin defence of his work, referring to that paper's review ofDr. No.[18]While referring to Bond's food and wine consumption as "gimmickery", Fleming bemoaned that "it has become an unfortunate trade-mark. I myself abhor Wine-and-Foodmanship. My own favourite food is scrambled eggs."[18]Fleming was so keen on scrambled eggs that he used his short story, "007 in New York",to provide his favourite recipe for the dish: in the story, this came from the housekeeper of Fleming's friend Ivar Bryce, May, who gave her name to Bond's own housekeeper.[48]Academic Edward Biddulph observed that Fleming fully described seventy meals within the book series and that while a number of these had items in common—such as scrambled eggs and steaks—each meal was different from the others.[65]

Smoking[edit]

Bond is a heavy smoker, at one point smoking 70 cigarettes a day.[66]Bond has his cigarettes custom-made by Morland of Grosvenor Street, mixing Balkan and Turkish tobacco and having a higher nicotine content than normal; the cigarettes have three gold bands on the filter.[67]Bond carried his cigarettes in a widegunmetalcigarette case which carried fifty; he also used a black oxidisedRonsonlighter.[68]The cigarettes were the same as Fleming's, who had been buying his at Morland since the 1930s; the three gold bands on the filter were added during the war to mirror his naval Commander's rank.[67]On average, Bond smokes sixty cigarettes a day, although he cut back to around twenty-five a day after his visit to a health farm inThunderball:[68]Fleming himself smoked up to 80 cigarettes a day.[69]

Drugs[edit]

Bond occasionally supplements his alcohol consumption with the use of other drugs, for both functional and recreational reasons:Moonrakersees Bond consume a quantity of theamphetamine benzedrineaccompanied by champagne, before his bridge game withSir Hugo Drax(also consuming a carafe of vintage Riga vodka and a vodka martini);[70]he also uses the drug for stimulation on missions, such as swimming across Shark Bay inLive and Let Die,[71]or remaining awake and alert when threatened in the Dreamy Pines Motor Court inThe Spy Who Loved Me.[49]

Cars[edit]

Bond was a car enthusiast and took great interest in his vehicles. InMoonraker,Fleming writes that "Bond had once dabbled on the fringe of the racing world",[72]implying Bond had raced in the past. Over the course of the 14 books, Bond owns three cars, all Bentleys. For the first three books of the series, Bond drives a supercharged 1930Bentley 4½ Litre,painted battleship grey, that he bought in 1933. During the War he kept the car in storage. He wrecks this car in May 1954 during the events ofMoonraker.[citation needed]

Bond subsequently purchases aBentley Mark VIdrophead coupé, using the money he won from Hugo Drax atBlades.This car is also painted battleship grey and has dark blue upholstery. Fleming refers to this car as a 1953 model, even though the last year for the mark was 1952. It is possible the 1953 year refers to the coachwork, which in this case would probably make it aGraber-bodied car.[citation needed]

InThunderball,Bond buys the wreck of aBentley R-Type Continentalwith a sports saloon body and 4.5 L engine. Produced between 1952 and 1955, Bentley built 208 of these cars, 193 of which hadH. J. Mullinerbodies. Bond's car would have been built before July 1954, as the engines fitted after this time were 4.9 L. Fleming curiously calls this car a "Mark II", a term which was never used. Bond replaces the engine with a Mark IV 4.9 L and commissions a body from Mulliners that was a "rather square convertible two-seater affair." He paints this car battleship grey and upholsters it in black. Later, against the advice of Bentley, he adds an Arnott supercharger. In 1957 Fleming had written to Rolls-Royce's Chairman,Whitney Straight,to get information about a new car for Bond. Fleming wanted the car to be a cross between aBentley Continentaland aFord Thunderbird.Straight pointed Fleming to chassis number BC63LC, which was probably the inspiration for the vehicle that ended up in the book. This car had been delivered in May 1954 to a Mr Silva as a Mulliner-bodied coupé. After he rolled the car and wrecked the body, Silva commissioned Mulliner to convert it to a drophead. However, Mulliner's price was too high and Silva eventually had the body built by Henri Chapron, with the work completed in July 1958. In 2008 the coachwork on this car was modified to match the proposed Mulliner conversion more closely.[73][failed verification]

-

1930 4.5 Litre Blower Bentley

-

1951 Bentley Mark VI with 1953 Graber body

-

Bentley R-Type Continental

Attitudes[edit]

According to academicJeremy Black,Bond is written as a complex character, even though he was also often the voice of Fleming's prejudices.[74]Throughout Fleming's books, Bond expressesracist,sexistandhomophobicattitudes.[75]The output of these prejudices, combined with the tales of Bond's actions, led journalistYuri Zhukovto write an article in 1965 for theSovietdaily newspaperPravda,describing Bond's values:

James Bond lives in a nightmarish world where laws are written at the point of a gun, where coercion and rape are considered valour and murder is a funny trick... Bond's job is to guard the interests of the property class, and he is no better than the youthsHitlerboasted he would bring up like wild beasts to be able to kill without thinking.

Yuri Zhukov,Pravda,30 September 1965.[76]

Black does not consider Bond to be the unthinking wild beast Zhukov writes about, however.[76]InFrom Russia, with Love,Bond watchesKerim Beyshoot the Bulgarian killer Krilencu and Bond observes that he had never killed anyone in cold blood.[77]In "The Living Daylights"Bond deliberately misses his target, realising the sniper he has been sent to kill is not a professional, but simply a beautiful female cello player.[78]Bond settles this in his mind by thinking that "It wasn'texactlymurder. Pretty near it, though. "[79]Goldfingeropens with Bond thinking through the experience of killing a Mexican assassin days earlier.[80]He is philosophical about it:

It was part of his profession to kill people. He had never liked doing it and when he had to kill he did it as well as he knew how and forgot about it. As a secret agent who held the rare double-O prefix—the licence to kill in the Secret Service—it was his duty to be as cool about death as a surgeon. If it happened, it happened. Regret was unprofessional—worse, it was a death-watch beetle in the soul.

Goldfinger,Chapter 1: Reflections in a Double Bourbon[81]

In response to a reviewer's criticism of Bond as villainous, Fleming said in a 1964Playboyinterview that he did not consider his character to be particularly evil or good: "I don't think that he is necessarily a good guy or a bad guy. Who is? He's got his vices and very few perceptible virtues except patriotism and courage, which are probably not virtues anyway... But I didn't intend for him to be a particularly likeable person." Fleming agreed with some critics' characterisation of Bond as an unthinking killer, but expressed that he was a product of his time: "James Bond is a healthy, violent, noncerebral man in his middle-thirties, and a creature of his era. I wouldn't say he's particularly typical of our times, but he's certainlyofthe times. "[82]

Another general attitude and prejudice of Fleming's that Bond gives voice to includes his approach tohomosexuality.While Fleming had a number of gay friends, includingNoël Cowardand his editor,William Plomer,he said that his books were "written for warm-bloodedheterosexuals".[83]His attitude went further, with Bond opining that homosexuals were "a herd of unhappy sexual misfits – barren and full of frustrations, the women wanting to dominate and the men to be nannied", adding that "he was sorry for them, but he had no time for them."[84]

Abilities[edit]

FromCasino RoyaletoFrom Russia, with LoveBond's preferred weapon is a.25 ACP Berettaautomatic pistol carried in a light-weightchamois leatherholster.[85]However, Fleming was contacted by a Bond enthusiast and gun expert,Geoffrey Boothroyd,who criticised Fleming's choice of firearm for Bond[86]and suggested aWalther PPK7.65mm instead.[87]Fleming used the suggestion inDr. No,also taking advice that it should be used with theBerns-Martintriple draw shoulder holster.[88]By way of thanks, the Secret Service Armourer who gives Bond his gun was given the nameMajor Boothroyd,and is introduced byM,Chief of the Secret Intelligence Service,as "the greatest small-arms expert in the world".[87]

I wish to point out that a man in James Bond's position would never consider using a.25 Beretta. It's really a lady's gun – and not a very nice lady at that! Dare I suggest that Bond should be armed with a.38 or a nine millimetre – let's say a German Walther PPK? That's far more appropriate.

Geoffrey Boothroyd,letter to Ian Fleming, 1956[89]

Kingsley Amis, inThe James Bond Dossier,noted that although Bond is a very good shot and the best in the Secret Service, he is still beaten by the instructor, something that added realism to Bond's character.[90]Amis identified a number of skills where Bond is very good, but is still beatable by others. These included skiing, hand-to-hand combat (elaborated in the SMERSH dossier on Bond inFrom Russia, With Loveas proficiency inboxingwith a good practical knowledge ofjudoholds), underwater swimming and golf.[91]Driving was also an ability Amis identified where Bond was good, but others were better;[91]one of those who is a better driver than Bond is SirHugo Drax,who causes Bond to write off his battleship-grey superchargedBentley 4½ Litre.[92]Bond subsequently drives a Mark II Continental Bentley, which he uses in the remaining books of the series,[93]although he is issued anAston Martin DB Mark IIIwith a homing device during the course ofGoldfinger.[93]

Continuation Bond works[edit]

John Gardner[edit]

In 1981, writerJohn Gardnerwas approached by the Fleming estate and asked to write a continuation novel for Bond.[94]Although he initially almost turned the series down,[95]Gardner subsequently wrote 14 original novels and two novelizations of the films betweenLicence Renewedin 1981[96]andCOLDin 1996.[97]With the influence of the American publishers,Putnam's,the Gardner novels showed an increase in the number of Americanisms used in the book, such as a waiter wearing "pants", rather than trousers, inThe Man from Barbarossa.[94]James Harker, writing inThe Guardian,considered that the Gardner books were "dogged by silliness",[94]giving examples ofScorpius,where much of the action is set inChippenham,andWin, Lose or Die,where "Bond gets chummy with an unconvincingMaggie Thatcher".[94]Ill health forced Gardner to retire from writing the Bond novels in 1996.[98]

Gardner stated that he wanted "to bring Mr Bond into the 1980s",[99]although he retained the ages of the characters as they were when Fleming had left them.[44]Even though Gardner kept the ages the same, he made Bond grey at the temples as a nod to the passing of the years.[100]Other 1980s effects also took place, with Bond smoking low-tar cigarettes[101]and becoming increasingly health conscious.[102]

The return of Bond in 1981 saw media reports on the morepolitically correctBond and his choice of car—aSaab 900Turbo;[98]Gardner later put him in aBentley Mulsanne Turbo.[103]Gardner also updated Bond's firearm: under Gardner, Bond is initially issued with theBrowning 9mmbefore changing to aHeckler & Koch VP70and then aHeckler & Koch P7.[44]Bond is also revealed to have taken part in the 1982Falklands War.[104]Gardner updated Fleming's characters and used contemporary political leaders in his novels; he also used the high-tech apparatus ofQ Branchfrom the films,[105]although Jeremy Black observed that Bond is more reliant on technology than his own individual abilities.[106]Gardner's series linked Bond to the Fleming novels rather than the film incarnations and referred to events covered in the Fleming stories.[107]

Raymond Benson[edit]

Following the retirement of John Gardner,Raymond Bensontook over as Bond author in 1996; as the first American author of Bond it was a controversial choice.[108]Benson had previously written the non-fictionThe James Bond Bedside Companion,first published in 1984.[109]Benson's first work was ashort story,"Blast from the Past",published in 1997.[110]By the time he moved on to other projects in 2002, Benson had written six Bond novels, three novelizations and three short stories.[111]His final Bond work wasThe Man with the Red Tattoo,published in 2002.[112]

In Bond novels and their ilk, the plot must threaten not only our hero but civilization as we know it. The icing on the cake is using exotic locales that "normal people" only fantasize about visiting, and slipping in essential dollops of sex and violence to build interest.

Raymond Benson[113]

Benson followed Gardner's pattern of setting Bond in the contemporary timeframe of the 1990s[114]and, according to Jeremy Black, had more echoes of Fleming's style than John Gardner,[115]he also changed Bond's gun back to theWalther PPK,[110]put him behind the wheel of aJaguar XK8[103]and made him swear more.[116]James Harker noted that "whilst Fleming's Bond had been anExpressreader; Benson's is positivelyred top.He's the first to havegroup sex... and the first to visit a prostitute ",[94]whilst Black notes an increased level of crudity lacking in either Fleming or Gardner.[115]In a 1998 interview Benson described his version of Bond as a more ruthless and darker character, stating that "Bond is not a nice guy. Bond is a killer... He is ananti-hero."[117]

Others[edit]

Kingsley Amis[edit]

In 1967, four years after Fleming's death, his literary executors,Glidrose Productions,approachedKingsley Amisand offered him £10,000 (£229,261 in 2023 pounds[118]) to write the first continuation Bond novel.[94]The result wasColonel Sunpublished in 1968 under the pen-name Robert Markham.[119]Journalist James Harker noted that although the book was not literary, it was stylish.[94]Raymond Benson noted that Bond's character and events from previous novels were all maintained inColonel Sun,[120]saying "he is the same darkly handsome man first introduced inCasino Royale".[121]

Sebastian Faulks[edit]

After Gardner and Benson had followed Amis, there was a gap of six years untilSebastian Faulkswas commissioned by Ian Fleming Publications to write a new Bond novel, which was released on 28 May 2008, the one hundredth anniversary of Ian Fleming's birth.[122]The book—entitledDevil May Care—was published in the UK byPenguin Booksand byDoubledayin the US.[123]

Faulks ignored the timeframe established by Gardner and Benson and instead reverted to that used by Fleming and Amis, basing his novel in the 1960s;[114]he also managed to use a number of the cultural touchstones of the sixties in the book.[124]Faulks was true to Bond's original character and background too, and provided "a Flemingesque hero"[114]who drove a battleship grey 1967T-series Bentley.[103]

Jeffery Deaver[edit]

On 26 May 2011 American writerJeffery Deaver,commissioned by Ian Fleming Publications, releasedCarte Blanche.[125]Deaver restarted the chronology of Bond, separate from the timelines of any of the previous authors, by stating he was born in 1980;[126]the novel also saw Bond in a post-9/11agency, independent of eitherMI5or MI6.[127]

The films didn't influence me at all and nor did the continuation novels. I wanted to get back to the original Bond who's dark and edgy, has quite a sense of irony and humour and is extremely patriotic and willing to sacrifice himself for Queen and country. He is extremely loyal but he has this dark pall over him because he's a hired killer – and he wrestles with that. I've always found him to be quite a representative of the modern era.

Jeffery Deaver[128]

Whilst the chronology changed, Deaver included a number of elements from the Fleming novels, including Bond's tastes for food and wine, his gadgets and "the rather preposterous names of some of the female characters".[126]

William Boyd[edit]

In 2013William Boyd's continuation novel,Solo,was released; it ignored Deaver's new timeframe and was set in 1969.[129]

Anthony Horowitz[edit]

In September 2015 the authorAnthony HorowitzreleasedTrigger Mortis;a novel containing material written, but previously unreleased, by Fleming.[130]It is set in 1957, two weeks after the events of Fleming's novelGoldfinger.[131]

In May 2018 Horowitz releasedForever and a Day;again containing unreleased material from Fleming. It is set in 1950, before the events ofCasino Royale,and thoroughly details the events leading up to Bond's promotion to 00-status, and becoming the character he is by the original Fleming novel.[132]

Horowitz released a third Bond novel,With a Mind to Kill,in 2022.[citation needed]This novel is set after the events ofThe Man with the Golden Gunand features MI6 sending Bond back to Russia to infiltrate the same group that brainwashed him to try and kill M, planting fake evidence that Bond succeeded in his mission. Bond is able to eliminate the head of the group and thwart a planned assassination, but the novel ends with him deciding to leave the service as he has grown jaded with his own role in the work, to the extent that he is in a position where he could be the target of a sniper and he expresses no concern about his fate.

Young Bond[edit]

In 2005, the author and comedianCharlie HigsonreleasedSilverFin,the first of five novels and one short story in the life of a young James Bond;[133]his final work was the short story "A Hard Man to Kill",released as part of the non-fiction workDanger Society: The Young Bond Dossier,the companion book to the Young Bond series.[134]Young Bond is set in the 1930s, which would fit the chronology with that of Fleming.[135]

I deliberately steered clear of anything post-Fleming. My books are designed to fit in with what Fleming wrote and nothing else. I also didn't want to be influenced by any of the other books... for now my Bible is Fleming.

Charlie Higson[136]

Higson stated that he was instructed by the Fleming estate to ignore all other interpretations of Bond, except the original Fleming version.[137]As the background to Bond's childhood, Higson used Bond's obituary inYou Only Live Twiceas well as his own and Fleming's childhoods.[138]In forming the early Bond character, Higson created the origins of some of Bond's character traits, including his love of cars and fine wine.[137]

Steve Cole continued the Young Bond storyline with four more novels.[citation needed]Higson went on to write an adult Bond novel,On His Majesty's Secret Service.[139]

Adaptations[edit]

Adaptations of Bond started early in Fleming's writings, withCBSpaying him $1,000[140]($11,300 in 2023 dollars[141]) to adapt his first novel,Casino Royale,into aone-hour television adventure;[142]this was broadcast on 21 October 1954.[143]The Bond character, played byBarry Nelson,was changed to "Card Sense" Jimmy Bond, an American agent working for "Combined Intelligence".[144]

In 1957 theDaily Expressnewspaper adapted Fleming's stories intocomic stripformat.[145]In order to help the artists, Fleming commissioned a sketch to show how he saw Bond; illustratorJohn McLuskyconsidered Fleming's version too "outdated" and "pre-war" and changed Bond to give him a more masculine look.[146]

In 1962Eon Productions,the company of CanadianHarry Saltzmanand AmericanAlbert R. "Cubby" Broccolireleased the first cinema adaptation of a Fleming novel,Dr. No,featuringSean Conneryas007.[147]Connery was the first of seven actors to play Bond on the cinema screen, six of whom appeared in the Eon series of films. As well as looking different, each of the actors has interpreted the role of Bond in a different way. Besides Connery, Bond has been portrayed on film byDavid Niven,George Lazenby,Roger Moore,Timothy Dalton,Pierce BrosnanandDaniel Craig.[148]

See also[edit]

- List of James Bond vehicles

- Outline of James Bond

- List of James Bond novels and short stories

- Bibliography of works on James Bond

References[edit]

- ^abCook, William (28 June 2004). "Novel man".New Statesman.p. 40.

- ^Lycett, Andrew(2004)."Fleming, Ian Lancaster (1908–1964) (subscription needed)".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33168.Retrieved19 November2011.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^Bennett & Woollacott 2003,p. 1.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 4.

- ^"Ian Fleming".About Ian Fleming.Ian Fleming Publications.Archived fromthe originalon 15 August 2011.Retrieved7 September2011.

- ^Black 2005,p. 4.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 19.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 5.

- ^"Obituary: Mr. Ian Fleming".The Times.13 August 1964. p. 12.

- ^Black 2005,p. 75.

- ^abcMacintyre, Ben (5 April 2008). "Bond – the real Bond".The Times.p. 36.

- ^"Obituary: Colonel Peter Fleming, Author and explorer".The Times.20 August 1971. p. 14.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 68-9.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 54.

- ^"Did a woman inspire Ian Fleming's James Bond?".BBC.8 December 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 8 December 2016.

- ^"James Bond, Ornithologist, 89; Fleming Adopted Name for 007".The New York Times.17 February 1989.Retrieved22 August2019.

- ^Hellman, Geoffrey T.(21 April 1962)."James Bond Comes to New York".Talk of the Town.The New Yorker.p. 32.Archivedfrom the original on 21 January 2012.Retrieved9 September2011.

- ^abcFleming, Ian (5 April 1958). ""The Exclusive Bond" Mr. Fleming on his hero ".The Manchester Guardian.London, England. p. 4.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 230.

- ^O'Brien, Liam (14 April 2013)."'The name's Secretan... James Secretan': Early draft of Casino Royale reveals what Ian Fleming wanted to call his super spy ".The Independent on Sunday.Archivedfrom the original on 15 April 2013.

- ^"'Real-life James Bond' from Swansea given 007 gravestone ".BBC. 18 April 2019.Retrieved2 August2021.

- ^Malvern, Jack (6 October 2018)."The name's Bond: Welsh lollipop man with an unlikely claim to fame".The Times.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 65.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 190.

- ^Amis 1966,p. 35.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 51.

- ^abBenson 1988,p. 62.

- ^Pearson 2008,p. 215.

- ^Black 2005,p. 176.

- ^Fleming 2006c,p. 11.

- ^Pearson 2008,p. 21.

- ^Griswold 2006,p. 27.

- ^abGriswold 2006,p. 7.

- ^Griswold 2006,p. 33.

- ^Fleming 2006b,p. 256–259.

- ^Buckton 2021,p. 286.

- ^abBenson 1988,p. 59.

- ^abcChancellor 2005,p. 59.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 205.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 58.

- ^abBenson 1988,p. 60.

- ^Pearson 2008,p. 42.

- ^abcChancellor 2005,p. 61.

- ^abcBenson 1988,p. 61.

- ^Griswold 2006,p. 14.

- ^Griswold 2006,p. 4.

- ^Correspondent, David Sanderson, Arts."The spy who lived here: author finds 'James Bond's bolt-hole'".The Times.ISSN0140-0460.Retrieved2 February2021.

{{cite news}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abChancellor 2005,p. 113.

- ^abcBenson 1988,p. 71.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 58.

- ^Fleming 2006c,p. 10–11.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 205.

- ^Comentale, Watt & Willman 2005,p. 166.

- ^Lycett 1996,p. 257.

- ^Fleming 2006a,p. 52–53.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 178.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 90.

- ^Johnson, Graham; Guha, Indra Neil; Davies, Patrick (12 December 2013)."Were James Bond's drinks shaken because of alcohol induced tremor?".British Medical Journal.347(f7255). London, England: BMJ Group: f7255.doi:10.1136/bmj.f7255.PMC3898163.PMID24336307.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 88.

- ^Benson 1988,p. 67.

- ^Pearson 2008,p. 299.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 85-6.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 87.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 169.

- ^Biddulph, Edward (1 June 2009). ""Bond Was Not a Gourmet": An Archaeology of James Bond's Diet ".Food, Culture and Society.12(2). Abingdon, Oxfordshire:Taylor & Francis:134.doi:10.2752/155280109X368688.S2CID141936771.(subscription required)

- ^Cabrera Infante 1985,p. 212.

- ^abChancellor 2005,p. 70.

- ^abBenson 1988,p. 70.

- ^Burns, John F.(19 May 2008)."Remembering Fleming, Ian Fleming".The New York Times.New York City.Archivedfrom the original on 23 May 2013.Retrieved22 November2011.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 176.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 77.

- ^Moonraker,ch. 18.

- ^"1954 Bentley R Type Drophead Coupe / BC63LC Vehicle Information".

- ^Black 2005,p. 40.

- ^Selman, Matt (28 August 2008)."The Quantum of Racist".Time Magazine.New York City:Time, Inc.Archivedfrom the original on 15 July 2017.

- ^abBlack 2005,p. 82.

- ^Lindner 2009,p. 71.

- ^Black 2005,p. 83.

- ^Fleming 2006e,p. 96.

- ^Comentale, Watt & Willman 2005,p. 244.

- ^Fleming 2006d,p. 3.

- ^Golson 1983,pp. 52–53.

- ^Macintyre 2008,p. 160.

- ^Fleming 2006d,p. 300.

- ^Griswold 2006,p. 39–40.

- ^Chancellor 2005,p. 160.

- ^abMacintyre 2008,p. 132.

- ^Benson 1988,p. 15.

- ^"Bond's unsung heroes: Geoffrey Boothroyd, the real Q".The Daily Telegraph.21 May 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2015.Retrieved24 November2011.

- ^Amis 1966,p. 17.

- ^abAmis 1966,p. 18.

- ^Benson 1988,pp. 62–63.

- ^abBenson 1988,p. 63.

- ^abcdefgHarker, James (2 June 2011)."James Bond's changing incarnations".The Guardian.London, England.Archivedfrom the original on 13 March 2018.Retrieved27 March2018.

- ^Simpson 2002,p. 58.

- ^"Licence Renewed".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications. Archived fromthe originalon 27 December 2010.Retrieved23 November2011.

- ^"Cold".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications. Archived fromthe originalon 27 December 2010.Retrieved23 November2011.

- ^abRipley, Mike (2 November 2007)."Obituary: John Gardner: Prolific thriller writer behind the revival of James Bond and Professor Moriarty".The Guardian.London, England. p. 41.Archivedfrom the original on 30 April 2014.Retrieved24 November2011.

- ^Black 2005,p. 185.

- ^Benson 1988,p. 149.

- ^Fox, Margalit (29 August 2007)."John Gardner, Who Continued the James Bond Series, Dies at 80".The New York Times.New York City. p. 21.Archivedfrom the original on 23 May 2013.Retrieved25 November2011.

- ^Benson 1988,p. 151.

- ^abcDavis, Kylie (23 November 2007). "A Bond with the devil".The Sydney Morning Herald.Sydney, Australia: Fairfax Media. p. 8.

- ^Black 2005,p. 188.

- ^"Obituary: John Gardner".The Times.9 August 2007. p. 65.

- ^Black 2005,p. 191.

- ^Benson 1988,p. 152.

- ^Binyon, Michael (20 January 2011). "Sex, spies and sunblock: James Bond feels the heat".The Times.pp. 13–14.

- ^Raymond Benson."Books—At a Glance".RaymondBenson.com.Archivedfrom the original on 27 November 2011.Retrieved3 November2011.

- ^abSimpson 2002,p. 62.

- ^"Raymond Benson".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications. Archived fromthe originalon 27 December 2010.Retrieved23 November2011.

- ^"The Man with the Red Tattoo".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications. Archived fromthe originalon 27 December 2010.Retrieved23 November2011.

- ^Benson, Raymond(November 2010). "The 007 way to write a thriller: The author of 6 official James Bond novels offers a process for building a compelling tale".The Writer.123(11). Braintree, Massachusetts: Madavor Media: 24–26.ISSN0043-9517.

- ^abcDugdale, John (29 May 2011). "Spy another day".The Sunday Times.p. 40.

- ^abBlack 2005,p. 198.

- ^Simpson 2002,p. 63.

- ^Newton, Chris (22 November 1998)."Benson, Raymond Benson turns from 007 fan club to 007 author".Observer-Reporter.Washington, Pennsylvania: Observer Publishing Co.

- ^UKRetail Price Indexinflation figures are based on data fromClark, Gregory (2017)."The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)".MeasuringWorth.Retrieved7 May2024.

- ^"Colonel Sun".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications. Archived fromthe originalon 27 December 2010.Retrieved25 November2011.

- ^Benson 1988,p. 146.

- ^Benson 1988,p. 147.

- ^"Faulks pens new James Bond novel".BBC News.11 July 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 12 February 2009.Retrieved25 November2011.

- ^"Sebastian Faulks".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications. Archived fromthe originalon 27 December 2010.Retrieved25 November2011.

- ^Weisman, John (22 June 2008). "Close to 007 original, but not quite".The Washington Times.Washington, DC: The Washington Times, LLC.

- ^"James Bond book called Carte Blanche".BBC News.17 January 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 19 March 2012.Retrieved25 November2011.

- ^abHickman, Angela (25 June 2011). "In others' words; Many iconic literary characters outlive their creators, presenting a unique challenge to the next authors in line".National Post.p. WP4.

- ^"Jeffery Deaver".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications. Archived fromthe originalon 15 April 2012.Retrieved25 November2011.

- ^Stephenson, Hannah (28 May 2011). "The mantle of James Bond has been passed to thriller writer Jeffery Deaver".Norwich Evening News.

- ^"William Boyd takes James Bond back to 1960s in new 007 novel".BBC News.London.BBC.12 April 2012.Archivedfrom the original on 12 April 2012.Retrieved12 April2012.

- ^"Anthony Horowitz to write new James Bond novel".BBC News.2 October 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2015.

- ^Flood, Alison (28 May 2015)."New James Bond novel Trigger Mortis resurrects Pussy Galore".The Guardian.Retrieved28 September2021.

- ^"Forever and a Day by Anthony Horowitz review – a prequel to Casino Royale".The Guardian.23 May 2018.Retrieved23 May2018.

- ^"Charlie Higson".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2012.Retrieved28 November2011.

- ^"Danger Society: The Young Bond Dossier".Puffin Books: Charlie Higson.Penguin Books.Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2012.Retrieved2 November2011.

- ^"Young Bond books".The Books.Ian Fleming Publications.Archivedfrom the original on 27 December 2010.Retrieved27 November2011.

- ^Cox, John (23 February 2005)."The Charlie Higson CBn Interview".CommanderBond.net.Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2011.Retrieved27 November2011.

- ^abTurner, Janice(31 December 2005). "Man and boy".The Times.p. 14.

- ^Malvern, Jack. "Shaken and stirred: the traumatic boyhood of James Bond".The Times.p. 26.

- ^Ramachandran, Naman (31 March 2023)."New James Bond Story 'On His Majesty's Secret Service' Commissioned to Celebrate King Charles' Coronation".Variety.

- ^Black 2005,p. 14.

- ^1634–1699:McCusker, J. J.(1997).How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda(PDF).American Antiquarian Society.1700–1799:McCusker, J. J.(1992).How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States(PDF).American Antiquarian Society.1800–present:Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis."Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–".Retrieved29 February2024.

- ^Lindner 2009,p. 14.

- ^Britton 2004,p. 30.

- ^Benson 1988,p. 11.

- ^Jütting 2007,p. 6.

- ^Simpson 2002,p. 21.

- ^Sutton, Mike."Dr. No (1962)".Screenonline.British Film Institute.Archived fromthe originalon 3 March 2016.Retrieved4 November2011.

- ^Cork & Stutz 2007,p. 23.

Bibliography[edit]

- Amis, Kingsley (1966).The James Bond Dossier.London:Pan Books.

- Bennett, Tony; Woollacott, Janet (2003). "The Moments of Bond". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.).The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader.Manchester:Manchester University Press.ISBN978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Benson, Raymond(1988).The James Bond Bedside Companion.London:Boxtree Ltd.ISBN978-1-85283-233-9.

- Black, Jeremy(2005).The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen.University of Nebraska Press.ISBN978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Buckton, Oliver (2021).The World is Not Enough: A Biography of Ian Fleming.Rowman & Littlefield.ISBN978-1-53-813858-8.

- Britton, Wesley Alan (2004).Spy television(2 ed.).Greenwood Publishing Group.ISBN978-0-275-98163-1.

- Cabrera Infante, Guillermo(1985).Holy Smoke.New York:Harper & Row.ISBN978-0-06-015432-5.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005).James Bond: The Man and His World.London:John Murray.ISBN978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Comentale, Edward P; Watt, Stephen; Willman, Skip (2005).Ian Fleming & James Bond: the cultural politics of 007.Indiana University Press.ISBN978-0-253-21743-1.

- Cork, John; Stutz, Collin (2007).James Bond Encyclopedia.London:Dorling Kindersley.ISBN978-1-4053-3427-3.

- Fleming, Ian(2006a).Casino Royale.London:Jonathan Cape.ISBN978-0-14-102830-9.

- Fleming, Ian (2006b).You Only Live Twice.London: Jonathan Cape.ISBN978-0-14-102826-2.

- Fleming, Ian (2006c).Moonraker.London: Jonathan Cape.ISBN978-0-14-102833-0.

- Fleming, Ian (2006d).Goldfinger.London: Jonathan Cape.ISBN978-0-14-102831-6.

- Fleming, Ian (2006e).Octopussy and The Living Daylights.London: Jonathan Cape.ISBN978-0-14-102834-7.

- Golson, G. Barry (1983).The Playboy Interview Volume II.London: Perigee Books.ISBN978-0-399-50769-4.

- Griswold, John (2006).Ian Fleming's James Bond: Annotations And Chronologies for Ian Fleming's Bond Stories.AuthorHouse.ISBN978-1-4259-3100-1.

- Jütting, Kerstin (2007)."Grow Up, 007!" – James Bond Over the Decades: Formula Vs. Innovation.GRIN Verlag.ISBN978-3-638-85372-9.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009).The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader.Manchester University Press.ISBN978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Lycett, Andrew(1996).Ian Fleming.London: Phoenix.ISBN978-1-85799-783-5.

- Macintyre, Ben(2008).For Your Eyes Only.London:Bloomsbury Publishing.ISBN978-0-7475-9527-4.

- Pearson, John(2008).James Bond: The Authorised Biography.Random House.ISBN978-0-09-950292-0.

- Simpson, Paul (2002).The Rough Guide to James Bond.Rough Guides.ISBN978-1-84353-142-5.

External links[edit]

Media related toJames Bond (character)at Wikimedia Commons

Media related toJames Bond (character)at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related toJames Bondat Wikiquote

Quotations related toJames Bondat Wikiquote- Ian Fleming's 'Red Indians' – 30AU – Literary James Bond's Wartime unit

- Characters in British novels of the 20th century

- Male characters in literature

- Male characters in film

- Fictional assassins

- Fictional MI6 agents

- Fictional British spies

- Literary characters introduced in 1953

- Fictional commanders

- Fictional gamblers

- Fictional gunfighters

- Orphan characters in literature

- Fictional Royal Navy personnel

- Dynamite Entertainment characters

- James Bond characters

- Fictional contract bridge players

- Fictional Special Boat Service personnel

- Fictional Scottish people