Jordan

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan | |

|---|---|

| Motto:الله، الوطن، الملك Allāh, al-Waṭan, al-Malik "God, Country, King"[1] | |

| Anthem:السلام الملكي الأردني Al-Salām al-Malakī al-Urdunī "The Royal Anthem of Jordan" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Amman 31°57′N35°56′E/ 31.950°N 35.933°E |

| Official languages | Arabic[2] |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion | 1% others |

| Demonym(s) | Jordanian |

| Government | Unitaryparliamentaryconstitutional monarchy |

| Abdullah II | |

| Jafar Hassan | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from theUnited Kingdom | |

| 11 April 1921 | |

| 25 May 1946 | |

| 11 January 1952 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 89,342 km2(34,495 sq mi) (110th) |

• Water (%) | 0.6 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 11,484,805[3](84th) |

• 2015 census | 9,531,712[4] |

• Density | 114/km2(295.3/sq mi) (70th) |

| GDP(PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP(nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini(2011) | 35.4[6] medium inequality |

| HDI(2022) | high(99th) |

| Currency | Jordanian dinar(JOD) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +962 |

| ISO 3166 code | JO |

| Internet TLD | .jo .الاردن |

Website jordan.gov.jo | |

Jordan,[a]officially theHashemite Kingdom of Jordan,[b]is a country in theSouthern Levantregion ofWest Asia.Jordan is bordered bySyriato the north,Iraqto the east,Saudi Arabiato the south, andIsraeland theoccupiedPalestinian territoriesto the west. TheJordan River,flowing into theDead Sea,is located along the country's western border. Jordan has a small coastline along theRed Seain its southwest, separated by theGulf of AqabafromEgypt.Ammanis the country's capital andlargest city,as well as themost populous city in the Levant.

Modern-day Jordan has been inhabited by humans since thePaleolithicperiod. Three kingdoms emerged inTransjordanat the end of theBronze Age:Ammon,MoabandEdom.In the third century BC, theArabNabataeansestablishedtheir kingdomcentered inPetra.Later rulers of the Transjordan region include theAssyrian,Babylonian,Roman,Byzantine,Rashidun,Umayyad,Abbasid,and theOttomanempires. After the 1916Great Arab Revoltagainst the Ottomans duringWorld War I,the greaterSyria regionwaspartitioned,leading to theestablishmentof theEmirate of Transjordanin 1921, which became a British protectorate. In 1946, the country gained independence and became officially known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.[c]The countrycaptured and annexedtheWest Bankduring the1948 Arab–Israeli Waruntil it was occupied by Israelin 1967.Jordanrenouncedits claim to the territory to thePalestiniansin 1988 and signed apeace treaty with Israelin 1994.

Jordan is asemi-aridcountry, covering an area of 89,342 km2(34,495 sq mi) with a population of 11.5 million, making it theeleventh-most populous Arab country.The dominant majority, or around 95% of the country's population, isSunni Muslim,with the rest being mostlyArab Christian.Jordan was mostly unscathed by the violence that swept the region following theArab Springin 2010. From as early as 1948, Jordan has accepted refugees from multiple neighbouring countries in conflict. An estimated 2.1 millionPalestinian refugees,most of whom hold Jordanian citizenship, as well as 1.4 millionSyrian refugees,were residing in Jordan as of 2015.[4]The kingdom is also a refuge for thousands ofChristian Iraqisfleeing persecution.[8][9]While Jordan continues to accept refugees, the large Syrian influx during the 2010s has placed substantial strain on national resources and infrastructure.[10]

The sovereign state is aconstitutional monarchy,but the king holds wide executive and legislative powers. Jordan is a founding member of theArab Leagueand theOrganisation of Islamic Cooperation.The country has a highHuman Development Index,ranking 99th, and is considered a lower middle income economy. TheJordanian economy,one of the smallest economies in the region, is attractive to foreign investors based upon a skilled workforce.[11]The country is a major tourist destination, also attracting medical tourism with its well-developedhealth sector.[12]Nonetheless, a lack of natural resources, large flow of refugees, and regional turmoil have hampered economic growth.[13]

Etymology

Jordan takes its name from theJordan River,which forms much of the country's northwestern border.[14]While several theories for the origin of the river's name have been proposed, it is most plausible that it derives from theHebrewwordYarad (Hebrew:ירד),meaning "the descender", reflecting the river's declivity.[15]Much of the area that makes up modern Jordan was historically calledTransjordan,meaning "across the Jordan"; the term is used to denote the lands east of the river.[15]TheHebrew Bibleuses the termHebrew:עבר הירדן,romanized:Ever ha'Yarden,lit. 'The other side of the Jordan' for the area.[15]

Early Arab chronicles call the riverAl-Urdunn(a term cognate to the HebrewYarden).[16]Jund Al-Urdunnwas a military district around the river in the early Islamic era.[16]Later, during theCrusadesin the beginning of the second millennium, a lordship was established in the area under the name ofOultrejordain.[17]

History

Ancient period

The oldest known evidence ofhominidhabitation in Jordan dates back at least 200,000 years.[18]Jordan is a rich source ofPaleolithichuman remains (up to 20,000 years old) due to its location within theLevant,where variousmigrations out of Africaconverged,[19]and its more humid climate during theLate Pleistocene,which resulted in the formation of numerous remains-preserving wetlands in the region.[20]Past lakeshore environments attracted different groups of hominids, and several remains of tools dating from the Late Pleistocene have been found there.[19]Scientists have found the world's oldest known evidence of bread-making at a 14,500-year-oldNatufiansite in Jordan's northeastern desert.[21]

During theNeolithicperiod (10,000–4,500 BC), there was a transition there from ahunter-gathererculture to a culture with established populous agricultural villages.[22]'Ain Ghazal,one such village located at a site in the eastern part of present-dayAmman,is one of the largest known prehistoric settlements in theNear East.[23]Dozens of plaster statuesof the human form, dating to 7250 BC or earlier, have been uncovered there; they are one of the oldest large-scale representations of humans ever found.[24]During theChalcolithic period(4500–3600 BC), several villages emerged in Transjordan includingTulaylet Ghassulin theJordan Valley;[25]a series of circular stone enclosures in the eastern basalt desert from the same period have long baffled archaeologists.[26]

Fortified towns and urban centres first emerged in the southern Levant early in theBronze Age(3600–1200 BC).[27]Wadi Feynanbecame a regional centre for copper extraction: the metal was exploited on a large scale to produce bronze.[28]Trade and movement of people in the Middle East peaked, spreading cultural innovations and whole civilizations to spread.[29]Villages in Transjordan expanded rapidly in areas with reliable water-resources and arable land.[29]Ancient Egyptianpopulations expanded towards the Levant and came to control both banks of the Jordan River.[30]

During theIron Age(1200–332 BC), after the withdrawal of the Egyptians, Transjordan was home to the kingdoms ofAmmon,EdomandMoab.[31]These peoples spokeSemitic languagesof theCanaanite group;archaeologists have concluded that their polities were tribal kingdoms rather than states.[31]Ammon was located in the Amman plateau; Moab in the highlands east of the Dead Sea; and Edom in the area aroundWadi Arabain the south.[31]The northwestern region of the Transjordan, known then asGilead,was settled by theIsraelites.[32]The three kingdoms continually clashed with the neighbouring Hebrew kingdoms ofIsraelandJudah,centered west of the Jordan River.[33]One record of this is theMesha Stele,erected by the Moabite kingMeshain 840 BC; in an inscription on it, he lauds himself for the building projects that he initiated in Moab and commemorates his glory and his victory against the Israelites.[34]The stele constitutes one of the most important archeological parallels toaccounts recorded in the Bible.[35]At the same time, Israel and the Kingdom ofAram-Damascuscompeted for control of the Gilead.[36][37]

Around 740–720 BC, Israel and Aram-Damascus were conquered by theNeo-Assyrian Empire.The kingdoms of Ammon, Edom and Moab were subjugated but were allowed to maintain some degree of independence.[38]Then in 627 BC, following after the disintegration of the Assyrians' empire,Babylonianstook control of the area.[38]Although the kingdoms supported the Babylonians against Judah in the 597 BCsack of Jerusalem,they rebelled against Babylon a decade later.[38]The kingdoms were reduced tovassals,a status they retained under thePersianandHellenicempires.[38]By the beginning ofRoman rulearound 63 BC, the kingdoms of Ammon, Edom and Moab had lost their distinct identities and were assimilated into the Roman culture.[31]Some Edomites survived longer – driven by the Nabataeans, they had migrated to southernJudea,which became known asIdumaea;they were later converted toJudaismby theHasmoneans.[39]

Classical period

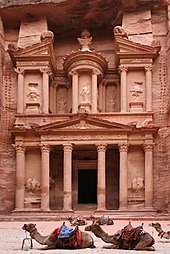

Alexander the Great'sconquestof the Persian Empire in 332 BC introducedHellenistic cultureto the Middle East.[40]After Alexander's death in 323 BC, theempire splitamong his generals, and in the end much of Transjordan was disputed between thePtolemiesbased in Egypt and theSeleucidsbased in Syria.[40]TheNabataeans,nomadic Arabs based south of Edom, managed to establish an independent kingdom in 169 BC by exploiting the struggle between the two Greek powers.[40]TheNabataean Kingdomcontrolled much of the trade routes of the region, and it stretched south along theRed Seacoast into theHejazdesert, up to as far north asDamascus,which it controlled for a short period (85–71 BC).[41]The Nabataeans massed a fortune from their control of the trade routes, often drawing the envy of their neighbours.[42]Petra, Nabataea's capital, flourished in the 1st century AD, driven by its extensive water irrigation systems and agriculture.[43]The Nabataeans were talentedstone carvers,building their most elaborate structure,Al-Khazneh,in the first century AD.[44]It is believed to be themausoleumof the Arab Nabataean KingAretas IV.[44]

Roman legions underPompeyconquered much of the Levant in 63 BC, inaugurating a period of Roman rule that lasted four centuries.[45]In 106 AD, EmperorTrajanannexed Nabataea unopposed and rebuilt theKing's Highwaywhich became known as theVia Traiana Novaroad.[45]The Romans gave the Greek cities of Transjordan—Philadelphia (Amman),Gerasa(Jerash),Gedara(Umm Quays),Pella(Tabaqat Fahl) andArbila(Irbid)—and other Hellenistic cities in Palestine and southern Syria, a level of autonomy by forming theDecapolis,a ten-city league.[46]Jerash is one of the best preserved Roman cities in the East; it was even visited by EmperorHadrianduring his journey to Palestine.[47]

In 324 AD, the Roman Empire split and the Eastern Roman Empire, later known as theByzantine Empire,continued to control or influence the region until 636.[48]Christianity hadbecome legal within the empire in 313after co-emperorsConstantineandLiciniussigned an edict of toleration.[48]In 380, theEdict of Thessalonicamade Christianity the official state religion. Transjordan prospered during the Byzantine era, and Christian churches were built throughout the region.[49]TheAqaba ChurchinAylawas built during this era; it is considered to be theworld's first purpose built Christian church.[50]Umm ar-Rasasin southern Amman contains at least 16 Byzantine churches.[51]Meanwhile, Petra's importance declined as sea trade routes emerged, and after a363 earthquakedestroyed many structures it declined further, eventually being abandoned.[44]TheSasanian Empirein the east became the Byzantines' rivals, andfrequent confrontationssometimes led to the Sasanids controlling some parts of the region, including Transjordan.[52]

Islamic era

In 629, during theBattle of Mu'tahin what is todayKarak Governorate,the Byzantines and theirArab Christian clients,theGhassanids,staved off an attack by a MuslimRashidunforce that marched northwards towards the Levant from the Hejaz.[53]The Byzantines however were defeated by the Muslims in 636 at the decisiveBattle of the Yarmukjust north of Transjordan.[53]Transjordan was an essential territory for the conquest of Damascus.[54]The Rashidun caliphate was followed by that of theUmayyads(661–750).[54]

Under the Umayyad Caliphate, severaldesert castleswere constructed in Transjordan, including:Qasr Al-MshattaandQasr Al-Hallabat.[54]TheAbbasid Caliphate's campaign to take over the Umayyad's began in a village in Transjordan known asHumayma.[55]The powerful749 earthquakeis thought to have contributed to the Umayyads'defeat by the Abbasids,who moved the caliphate's capital from Damascus toBaghdad.[55]During Abbasid rule (750–969), several Arab tribes moved northwards and settled in the Levant.[54]As had happened during the Roman era, growth of maritime trade diminished Transjordan's central position, and the area became increasingly impoverished.[56]After the decline of the Abbasids, Transjordan was ruled by theFatimid Caliphate(969–1070), then by theCrusaderKingdom of Jerusalem(1115–1187).[57]

The Crusaders constructed several castles as part of the Lordship of Oultrejordain, includingMontrealand Al-Karak.[58]During theBattle of Hattin(1187) nearLake Tiberiasjust north of Transjordan, the Crusaders lost toSaladin,the founder of theAyyubid dynasty(1187–1260).[59]The Ayyubids built theAjloun Castleand rebuilt older castles to be used as military outposts against the Crusaders.[59]Villages in Transjordan under the Ayyubids became important stops for Muslim pilgrims going toMeccawho travelled along the route that connected Syria to the Hejaz.[60]Several of the Ayyubid castles were used and expanded by theMamluks(1260–1516), who divided Transjordan between the provinces of Karak and Damascus.[61]During the next century Transjordan experiencedMongolattacks, but the Mongols were ultimately repelled by the Mamluks at theBattle of Ain Jalut(1260).[62]

In 1516 theOttoman Caliphate's forcesconquered Mamluk territory.[63]Agricultural villages in Transjordan witnessed a period of relative prosperity in the 16th century but were later abandoned.[64]Transjordan was of marginal importance to the Ottoman authorities.[65]As a result, Ottoman presence was virtually absent and reduced to annual tax collection visits.[64]

More ArabBedouintribes moved into Transjordan from Syria and the Hejaz during the first three centuries of Ottoman rule, including theAdwan,theBani Sakhrand theHoweitat.[66]These tribes laid claims to different parts of the region, and with the absence of a meaningful Ottoman authority, Transjordan slid into a state of anarchy that continued until the 19th century.[67]This led to a short-lived occupation by theWahhabiforces (1803–1812), an ultra-orthodox Islamic movement that emerged inNajd(in modern-day Saudi Arabia).[68]Ibrahim Pasha,son of thegovernorof theEgypt Eyalet,rooted out the Wahhabisunder the request of the Ottoman sultan by 1818.[69]

In 1833 Pasha turned on the Ottomans and established his rule over the Levant.[70]His policies led to the unsuccessfulpeasants' revolt in Palestinein 1834.[70]Transjordanian cities ofAs-Saltand Al-Karakwere destroyedby Pasha's forces for harboring apeasants' revolt leader.[70]Egyptian rule wasforcibly endedin 1841, with Ottoman rule restored.[70]Only after Pasha's campaign did the Ottoman Empire try to solidify its presence in theSyria Vilayet,which Transjordan was part of.[71]

A series of tax and land reforms (Tanzimat) in 1864 brought some prosperity back to agriculture and to abandoned villages; the end of virtual autonomy led a backlash in other areas of Transjordan.[71]MuslimCircassiansandChechens,fleeingRussian persecution,sought refuge in the Levant.[72]In Transjordan and with Ottoman support, Circassians first settled in the long-abandoned vicinity of Amman in 1867 and later in the surrounding villages.[72]The Ottoman authorities' establishment of its administration, conscription and heavy taxation policies led to revolts in the areas it controlled.[73]Transjordan's tribes in particular revolted during theShoubak(1905) and theKarak revolts(1910), which were brutally suppressed.[72]The construction of theHejaz Railwayin 1908—stretching across the length of Transjordan and linkingDamascuswithMedina—helped the population economically, as Transjordan became a stopover for pilgrims.[72]

Modern era

Increasing policies ofTurkificationand centralization adopted by the Ottoman Empire in the wake of the 1908Young Turk Revolutiondisenchanted the Arabs of the Levant, which contributed to the development of anArab nationalistmovement. These changes led to the outbreak of the 1916Arab RevoltduringWorld War I,which ended four centuries of stagnation under Ottoman rule.[72]The revolt was led bySharif Husseinof Mecca, scion of theHashemite familyof the Hejaz, and his sonsAbdullah,FaisalandAli.Locally, the revolt garnered the support of the Transjordanian tribes, including Bedouins, Circassians andChristians.[74]TheAllies of World War I,including Britain and France whose imperial interests converged with the Arabist cause, offered support.[75]The revolt started on 5 June 1916 from Medina and pushed northwards until the fighting reached Transjordan in theBattle of Aqabaon 6 July 1917.[76]The revolt reached its climax when Faisal entered Damascus in October 1918 and established an Arab-led military administration inOETA East,later declared as theArab Kingdom of Syria,both of which Transjordan was part of.[74]During this period, the southernmost region of the country, includingMa'anandAqaba,was alsoclaimed bythe neighbouringKingdom of Hejaz.

The nascent Hashemite Kingdom over theregion of Syriawas forced to surrender to French troops on 24 July 1920 during theBattle of Maysalun;[77]the French occupied only the northern part of Syria, leavingTransjordan in a period of interregnum.Arab aspirations failed to gain international recognition, due mainly to the secret 1916Sykes–Picot Agreement,which divided the region into French and British spheres of influence, and the 1917Balfour Declaration,in which Britain announced its support for the establishment of a "national home" for Jews in Palestine.[78]This was seen by the Hashemites and the Arabs as a betrayal of their previous agreements with the British,[79]including the 1915McMahon–Hussein Correspondence,in which the British stated their willingness to recognize the independence of a unified Arab state stretching fromAleppotoAdenunder the rule of the Hashemites.[80]

BritishHigh CommissionerHerbert Samueltravelled to Transjordan on 21 August 1920 to meet with As-Salt's residents. He there declared to a crowd of 600 Transjordanian notables that the British government would aid the establishment of local governments in Transjordan, which was to be kept separate from that of Palestine. The second meeting took place inUmm Qaison 2 September, where the British representative MajorFitzroy Somersetreceived a petition that demanded: an independent Arab government in Transjordan to be led by an Arab prince (emir); land sale in Transjordan toJewsbe stopped as well as the prevention of Jewish immigration there; that Britain establish and fund a national army; and that free trade be maintained between Transjordan and the rest of the region.[81]

Abdullah, the second son of Sharif Hussein,arrived from Hejaz by train in Ma'anin southern Transjordan on 21 November 1920 to redeem the Greater Syrian Kingdom his brother had lost.[82]Transjordan then was in disarray, widely considered to be ungovernable with its dysfunctional local governments.[83]Abdullah gained the trust of Transjordan's tribal leaders before scrambling to convince them of the benefits of an organized government.[84]Abdullah's successes drew the envy of the British, even when it was in their interest.[85]The British reluctantly accepted Abdullah as ruler of Transjordan after having given him a six-month trial.[86]In March 1921, the British decided to add Transjordan to theirMandate for Palestine,in which they would implement their "Sharifian Solution"policy without applying the provisions of the mandate dealing with Jewish settlement. On 11 April 1921 theEmirate of Transjordanwas established with Abdullah as emir.[87]

In September 1922, the Council of theLeague of Nationsrecognized Transjordan as a state under the terms of theTransjordan memorandum.[88][89]Transjordan remained a British mandate until 1946, but it had been granted a greater level of autonomy than the region west of the Jordan River.[90]Multiple difficulties emerged upon the assumption of power in the region by the Hashemite leadership.[91]In Transjordan, small localrebellions at Kurain 1921 and 1923 were suppressed by Abdullah's forces with the help of the British.[91]Wahhabis from Najd regained strength andrepeatedly raidedthe southern parts of his territory, seriously threatening the emir's position.[91]The emir was unable to repel those raids without the aid of the local Bedouin tribes and the British, who maintained a military base with a smallRoyal Air Forcedetachment close to Amman.[91]

Post-independence

TheTreaty of London,signed by the British government and the Emir of Transjordan on 22 March 1946, recognised the independence of the state.[92]On 25 May 1946, the day that the treaty was ratified by the Transjordan parliament, Transjordan was raised to the status of a kingdom under the name of theHashemite Kingdom of Jordanin Arabic, with Abdullah as its first king; although it continued to be referred to as the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan in English until 1949.[93][94]25 May is now celebrated as the nation'sIndependence Day,apublic holiday.[95]Jordan became a member of the United Nations on 14 December 1955.[96]

On 15 May 1948, as part of the1948 Arab–Israeli War,Jordan intervened inPalestinetogether with many other Arab states.[97]Following the war, Jordan controlled theWest Bank,and on 24 April 1950 Jordan formallyannexed these territoriesafter theJericho Conference.[98][99]In response, some Arab countries demanded Jordan's expulsion from theArab League.[98]On 12 June 1950, the Arab League declared that the annexation was a temporary, practical measure and that Jordan was holding the territory as a "trustee" pending a future settlement.[100]

King Abdullah was assassinated at theAl-Aqsa Mosquein 1951 by a Palestinian militant, amid rumors he intended to sign a peace treaty with Israel.[101]Abdullah was succeeded by his sonTalal,who established thecountry's modern constitutionin 1952.[102]Illness caused Talal to abdicate to his eldest sonHussein,[102]who ascended to the throne in 1953 at age 17.[101]Jordan witnessed great political uncertainty in the following period.[103]The 1950s was a period of political upheaval, asNasserismandPan-Arabismswept the Arab World.[103]On 1 March 1956, King HusseinArabized the command of the Armyby dismissing a number of senior British officers, an act made to remove remaining foreign influence in the country.[104]In 1958, Jordan and neighbouringHashemite Iraqformed theArab Federationas a response to the formation of the rivalUnited Arab Republicbetween Nasser's Egypt and Syria.[105]The union lasted only six months, being dissolved after Iraqi KingFaisal II(Hussein's cousin) was deposed by a bloodymilitary coup on 14 July 1958.[105]

Jordan signed a military pact with Egypt just before Israel launched a preemptive strike on Egypt to begin theSix-Day Warin June 1967, where Jordan and Syria joined the war.[106]The Arab states were defeated, and Jordan lost control of the West Bank to Israel.[106]TheWar of Attritionwith Israel followed, which included the 1968Battle of Karamehwhere the combined forces of theJordanian Armed Forcesand thePalestine Liberation Organization(PLO) repelled an Israeli attack on theKaramehcamp on the Jordanian border with the West Bank.[106]Despite the fact that the Palestinians had limited involvement against the Israeli forces, the events at Karameh gained wide recognition and acclaim in the Arab world.[107]As a result, there was an upsurge of support for Palestinian paramilitary elements (thefedayeen) within Jordan from other Arab countries.[107]The fedayeen activities soon became a threat to Jordan's rule of law.[107]In September 1970, the Jordanian army targeted the fedayeen and the resultant fighting led to the expulsion of Palestinian fighters from various PLO groups into Lebanon, in a conflict that became known asBlack September.[107]

In 1973, Egypt and Syria waged theYom Kippur Waron Israel, and fighting occurred along the 1967Jordan Rivercease-fire line.[107]Jordan sent a brigade to Syria to attack Israeli units on Syrian territory but did not engage Israeli forces from Jordanian territory.[107]At theRabat summit conferencein 1974, in the aftermath of the Yom-Kippur War, Jordan and the rest of the Arab League agreed that the PLO was the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people".[107]Subsequently, Jordanrenouncedits claims to the West Bank in 1988.[107]

At the1991 Madrid Conference,Jordan agreed to negotiate a peace treaty sponsored by the US and the Soviet Union.[107]TheIsrael–Jordan peace treatywas signed on 26 October 1994.[107]In 1997, in retribution fora bombing,Israeli agents entered Jordan using Canadian passports and poisonedKhaled Meshal,a seniorHamasleader living in Jordan.[107]Bowing to intense international pressure, Israel provided an antidote to the poison and released dozens of political prisoners, includingSheikh Ahmed Yassin,after King Hussein threatened to annul the peace treaty.[107]

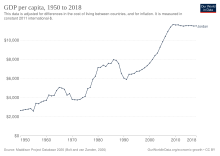

On 7 February 1999,Abdullah IIascended the throne upon the death of his father Hussein, who had ruled for nearly 50 years.[108]Abdullah embarked on economic liberalization when he assumed the throne, and his reforms led to an economic boom which continued until 2008.[109]Abdullah II has been credited with increasing foreign investment, improving public-private partnerships and providing the foundation forAqaba's free-trade zone and Jordan's flourishing information and communication technology sector.[109]He also set up five other special economic zones.[109]However, during the following years Jordan's economy experienced hardship as it dealt with the effects of theGreat Recessionand spillover from theArab Spring.[110]

Al-QaedaunderAbu Musab al-Zarqawi's leadership launchedcoordinated explosionsin three hotel lobbies in Amman on 9 November 2005, resulting in 60 deaths and 115 injured.[111]The bombings, which targeted civilians, caused widespread outrage among Jordanians.[111]The attack is considered to be a rare event in the country, and Jordan'sinternal securitywas dramatically improved afterwards.[111]No major terrorist attacks have occurred since then.[112]Abdullah and Jordan are viewed with contempt by Islamic extremists for the country's peace treaty with Israel, its relationship with the West, and its mostly non-religious laws.[113]

The Arab Spring were large-scale protests that erupted in theArab worldin 2011, demanding economic and political reforms.[114]Many of these protests tore down regimes in some Arab nations, leading to instability that ended with violent civil wars.[114]In response todomestic unrest,Abdullah replaced his prime minister and introduced reforms including reforming the constitution and laws governing public freedoms and elections.[114]Proportional representation was re-introduced to the Jordanian parliament in the2016 general election,a move which he said would eventually lead to establishing parliamentary governments.[115]Jordan was left largely unscathed from the violence that swept the region despite an influx of 1.4 million Syrian refugees into the natural resources-lacking country and the emergence of theIslamic State of Iraq and the Levant(ISIL).[115]

On 4 April 2021,19 people were arrested,includingPrince Hamzeh,the former crown prince of Jordan, who was placed under house arrest, after having been accused of working to "destabilize" the kingdom.

Geography

Jordan sits strategically at the crossroads of the continents of Asia, Africa and Europe,[116]in theLevantarea of theFertile Crescent,acradle of civilization.[117]Its area is 89,341 square kilometres (34,495 sq mi), and it is 400 kilometres (250 mi) long between its northernmost and southernmost points;Umm QaisandAqabarespectively.[14]The kingdom lies between29°and34° N,and34°and40° E.It is bordered bySaudi Arabiatothe southand the east,Iraqtothe north-east,Syriatothe north,andIsraelandPalestine(West Bank) to the west.

The east is an arid plateau irrigated byoasesand seasonal streams.[14]Major cities are overwhelmingly located on the north-western part of the kingdom with its fertile soils and relatively abundant rainfall.[118]These includeIrbid,JerashandZarqain the northwest, the capitalAmmanandAs-Saltin the central west, andMadaba,Al-Karakand Aqaba in the southwest.[118]Major towns in the east are the oasis towns ofAzraqandRuwaished.[117]

In the west, a highland area of arable land and Mediterranean evergreen forestry drops suddenly into theJordan Rift Valley.[117]The rift valley contains theJordan Riverand theDead Sea,which separates Jordan from Israel.[117]Jordan has a 26 kilometres (16 mi) shoreline on theGulf of Aqabain theRed Seabut is otherwise landlocked.[119]TheYarmuk River,an eastern tributary of the Jordan, forms part of the boundary between Jordan and Syria (including theGolan Heights) to the north.[119]The other boundaries are formed by several international and local agreements and do not follow well-defined natural features.[117]The highest point isJabal Umm al Dami,at 1,854 m (6,083 ft) above sea level, while the lowest is the Dead Sea −420 m (−1,378 ft), thelowest land point on Earth.[117]

Jordan has a diverse range of habitats, ecosystems and biota because of its varied landscapes and environments.[120]TheRoyal Society for the Conservation of Naturewas set up in 1966 to protect and manage Jordan's natural resources.[121]Nature reserves in Jordaninclude theDana Biosphere Reserve,theAzraq Wetland Reserve,theShaumari Wildlife Reserveand theMujib Nature Reserve.[121]

Climate

The climate varies greatly; generally, the further inland from the Mediterranean, there are greater contrasts in temperature and less rainfall.[14]The average elevation is 812 m (2,664 ft) above sea level.[14]The highlands above the Jordan Valley, mountains of the Dead Sea and WadiArabaand as far south as Ras Al-Naqab are dominated by aMediterranean climate,while the eastern and northeastern areas of the country are arid desert.[122]Although the deserts reach high temperatures, the heat is usually moderated by low humidity and a daytime breeze, while the nights are cool.[123]

Summers, lasting from May to September, are hot and dry, with temperatures averaging around 32 °C (90 °F) and sometimes exceeding 40 °C (104 °F) between July and August.[123]The winter, lasting from November to March, is relatively cool, with temperatures averaging around 11.08 °C (52 °F).[122]Winter also sees frequent showers and occasional snowfall in some western elevated areas.[122]

Biodiversity

Over 2,000 plant species have been recorded.[124]Many of the flowering plants bloom in the spring after the winter rains and the type of vegetation depends largely on the levels of precipitation. The mountainous regions in the northwest are clothed in forests, while further south and east the vegetation becomes more scrubby and transitions to steppe-type vegetation.[125]Forests cover 1.5 milliondunums(1,500 km2), less than 2% of Jordan, making Jordan among the world's least forested countries, the international average being 15%.[126]

Plant species and genera include theAleppo pine,Sarcopoterium,Salvia dominica,black iris,Tamarix,Anabasis,Artemisia,Acacia,Mediterranean cypressandPhoenecian juniper.[127]The mountainous regions in the northwest are clothed in natural forests ofpine,deciduous oak,evergreen oak,pistachioand wildolive.[128]Mammal and reptile species include, thelong-eared hedgehog,Nubian ibex,wild boar,fallow deer,Arabian wolf,desert monitor,honey badger,glass snake,caracal,golden jackaland theroe deer,among others.[129][130][131]Bird include thehooded crow,Eurasian jay,lappet-faced vulture,barbary falcon,hoopoe,pharaoh eagle-owl,common cuckoo,Tristram's starling,Palestine sunbird,Sinai rosefinch,lesser kestrel,house crowand thewhite-spectacled bulbul.[132]

Four terrestrial ecoregions lie with Jordan's borders:Syrian xeric grasslands and shrublands,Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests,Mesopotamian shrub desert,andRed Sea Nubo-Sindian tropical desert and semi-desert.[133]

Government and politics

Jordan is aunitary stateunder aconstitutional monarchy.Itsconstitution,adopted in 1952 and amended a number of times since, is the legal framework that governs the monarch, government, bicameral legislature and judiciary.[134]The king retains wide executive and legislative powers from thegovernmentandparliament.[135]The king exercises his powers through the government that he appoints for a four-year term, which is responsible before the parliament that is made up of two chambers: theSenateand theHouse of Representatives.The judiciary is independent according to the constitution but in practice often lacks independence.[134]

The king is thehead of stateandcommander-in-chiefof theArmed Forces.He can declare war and peace, ratify laws and treaties, convene and close legislative sessions, call and postpone elections, dismiss the government, and dissolve the parliament.[134]The appointed government can also be dismissed through a majorityvote of no confidenceby the elected House of Representatives. After a bill is proposed by the government, it must be approved by the House of Representatives then the Senate and becomes law after being ratified by the king. A royal veto on legislation can be overridden by atwo-thirds votein a joint session of both houses. The parliament also has the right ofinterpellation.[134]

The 65 members of the upper Senate are directly appointed by the king, the constitution mandates that they be veteran politicians, judges and generals who previously served in the government or in the House of Representatives.[136]The 130 members of the lower House of Representatives are elected throughparty-list proportional representationin 23 constituencies for a 4-year term.[137]Minimum quotas exist in the House of Representatives for women (15 seats, though they won 20 seats in the 2016 election), Christians (9 seats) andCircassiansandChechens(3 seats).[138]

Courts are divided into three categories: civil, religious, and special.[139]The civil courts deal with civil and criminal matters, including cases brought against the government.[139]The civil courts include magistrate courts, courts of first instance, courts of appeal,[139]high administrative courts which hear cases relating to administrative matters,[140]and the constitutional court which was set up in 2012 in order to hear cases regarding the constitutionality of laws.[141]AlthoughIslamis thestate religion,the constitution preservesreligiousand personal freedoms. Religious law only extends to matters of personal status such as divorce and inheritance in religious courts, and is partially based on Islamicsharialaw.[142]The special court deals with cases forwarded by the civil one.[143]

The monarch,Abdullah II,ascended to the throne in February 1999 after the death of his father KingHussein.Abdullah re-affirmed Jordan's commitment to thepeace treatywithIsraeland its relations with the United States. He refocused the government's agenda on economic reform during his first year. King Abdullah's eldest son,Prince Hussein,is the Crown Prince of Jordan.[144]The prime minister isJafar Hassanwho was appointed on 15 September 2024.[145]Abdullah had announced his intention to move Jordan to aparliamentary system,where the largest bloc in parliament forms a government. However, the underdevelopment of political parties in a country where tribal identity remains strong has hampered the effort.[146]Jordan has approximately 50 political parties representing nationalist, leftist, Islamist, and liberal ideologies.[147]Political parties contested one-fifth of the seats in the2016 elections,the remainder belonging to independent politicians.[148]

Freedom Houseranked Jordan as "Not Free" in theFreedom in the World2022 report.[149]Jordan ranked 94th globally in theCato Institute'sHuman Freedom Indexin 2021,[150]and ranked 58th in theCorruption Perceptions Indexissued byTransparency Internationalin 2021.[151]In the 2023Press Freedom IndexbyReporters Without Borders,Jordan ranked 146 out of 180 countries. The overall score for Jordan was 42.79, based on a scale from 0 (least free) to 105 (most free). The 2015 report noted "the Arab Spring and the Syrian conflict have led the authorities to tighten their grip on the media and, in particular, the Internet, despite an outcry from civil society".[152]Jordanian media consists of public and private institutions. Popular Jordanian newspapers includeAl Ghadand theJordan Times.Al-Mamlaka,Roya TVandJordan TVare some Jordanian television channels.[153]Internet penetration in Jordan reached 76% in 2015.[154]

Largest cities

The capital city isAmman,located in north-central Jordan.[155]

| Rank | Name | Governorate | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Amman  Zarqa |

1 | Amman | Amman Governorate | 1,812,059 |  Irbid  Russeifa | ||||

| 2 | Zarqa | Zarqa Governorate | 635,160 | ||||||

| 3 | Irbid | Irbid Governorate | 502,714 | ||||||

| 4 | Russeifa | Zarqa Governorate | 472,604 | ||||||

| 5 | Ar-Ramtha | Amman Governorate | 155,693 | ||||||

| 6 | Aqaba | Aqaba Governorate | 148,398 | ||||||

| 7 | Al-Mafraq | Mafraq Governorate | 106,008 | ||||||

| 8 | Madaba | Madaba Governorate | 105,353 | ||||||

| 9 | As-Salt | Balqa Governorate | 99,890 | ||||||

| 10 | Jerash | Jerash Governorate | 50,745 | ||||||

Administrative divisions

Jordan is divided into 12governorates(muhafazah) informally grouped into three regions: northern, central, southern. The governorates are divided intoliwaor districts, which are often further subdivided intoqdaor sub-districts.[157]Control for each administrative unit is in a "chief town" (administrative centre) known as anahia.[157]

| Map | Governorate | Capital | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern region | |||||

| 1 | Irbid | Irbid | 1,770,158 | ||

| 2 | Mafraq | Mafraq | 549,948 | ||

| 3 | Jerash | Jerash | 237,059 | ||

| 4 | Ajloun | Ajloun | 176,080 | ||

| Central region | |||||

| 5 | Amman | Amman | 4,007,256 | ||

| 6 | Zarqa | Zarqa | 1,364,878 | ||

| 7 | Balqa | As-Salt | 491,709 | ||

| 8 | Madaba | Madaba | 189,192 | ||

| Southern region | |||||

| 9 | Karak | Al-Karak | 316,629 | ||

| 10 | Aqaba | Aqaba | 188,160 | ||

| 11 | Ma'an | Ma'an | 144,083 | ||

| 12 | Tafilah | Tafila | 96,291 | ||

Foreign relations

The kingdom has followed a pro-Westernforeign policyand maintained close relations with the United States and the United Kingdom. During the firstGulf War(1990), these relations were damaged by Jordan's neutrality and its maintenance of relations with Iraq. Later, Jordan restored its relations with Western countries through its participation in the enforcement ofUN sanctions against Iraqand in the Southwest Asia peace process. After King Hussein's death in 1999, relations between Jordan and the Persian Gulf countries greatly improved.[158]

Jordan is a key ally of the US and UK and, together with Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, is one of only threeArab nationsto have signed peace treaties with Israel, Jordan's direct neighbour.[159]Jordan views an independent Palestinian state with the1967 bordersas part of thetwo-state solutionand of supreme national interest.[160]The ruling Hashemite dynasty has had custodianship over holy sites in Jerusalem since 1924, a position reinforced in the Israel–Jordan peace treaty. Turmoil in Jerusalem'sAl-Aqsamosque between Israelis and Palestinians created tensions between Jordan and Israel concerning the former's role in protecting the Muslim and Christian sites in Jerusalem.[161]

Jordan is a founding member of theOrganisation of Islamic Cooperationand of theArab League.[162][163]It enjoys "advanced status" with the European Union and is part of theEuropean Neighbourhood Policy,which aims to increase links between the EU and its neighbours.[164]Jordan andMoroccotried to join theGulf Cooperation Councilin 2011, but the Gulf countries offered a five-year development aid programme instead.[165]

Military

The first organised army in Jordan was established on 22 October 1920, named the "Arab Legion".[91]The Arab Legion grew from 150 men in 1920 to 8,000 in 1946.[166]Jordan's capture of the West Bank during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War proved that the Arab Legion, known today as the Jordan Armed Forces, was the most effective among the Arab troops involved in the war.[166]TheRoyal Jordanian Army,which boasts around 110,000 personnel, is considered to be among the most professional in the region and is particularly well-trained and organised.[166]The Jordanian military enjoys strong support and aid from the United States, the United Kingdom and France. This is due to Jordan's critical position in the Middle East.[166]The development ofSpecial Operations Forceshas been particularly significant, enhancing the capability of the military to react rapidly to threats to homeland security, as well as training special forces from the region and beyond.[167]Jordan provides extensive training to the security forces of several Arab countries.[168]

There are about 50,000 Jordanian troops working with the United Nations inpeacekeepingmissions across the world. Jordan ranks third internationally in participation in U.N. peacekeeping missions,[169]with one of the highest levels of peacekeeping troop contributions of all U.N. member states.[170]Jordan has dispatched several field hospitals to conflict zones and areas affected by natural disasters across the region.[171]

In 2014, Jordan joined an aerial bombardment campaign by an international coalition led by the United States against theIslamic Stateas part of its intervention in theSyrian Civil War.[172]In 2015, Jordan participated in theSaudi Arabian-led military intervention in Yemenagainst theHouthisand forces loyal to former PresidentAli Abdullah Saleh,who was deposed in the 2011 uprising.[173]

Law enforcement

Law enforcement is under the purview of thePublic Security Directorate(which includes approximately 50,000 persons) and theGeneral Directorate of Gendarmerie,both of which are subordinate to theMinistry of Interior.The first police force was organised after the fall of the Ottoman Empire on 11 April 1921.[174]Until1956police duties were carried out by the Arab Legion and theTransjordan Frontier Force.After that year the Public Safety Directorate was established.[174]The number of female police officers is increasing. In the 1970s, it was the first Arab country to include women in its police force.[175]Jordan's law enforcement was ranked 37th in the world and 3rd in the Middle East, in terms of police services' performance, by the 2016 World Internal Security and Police Index.[176][177]

Economy

Jordan is classified by theWorld Bankas a lower middle income country.[178]Approximately 15.7% of the population lives below the national poverty line as of 2018,[179]while almost a third fell below the national poverty line during some time of the year, known astransient poverty.[180]The economy, which has a GDP of $39.453 billion (as of 2016[update]),[5]grew at an average rate of 8% per annum between 2004 and 2008, and around 2.6% 2010 onwards.[14]GDP per capita rose by 351% in the 1970s, declined 30% in the 1980s, and rose 36% in the 1990s—currently $9,406 per capita bypurchasing power parity.[181]The Jordanian economy is one of the smallest economies in the region, and the country's populace suffers from relatively high rates of unemployment and poverty.[14]

The economy is relatively well diversified. Trade and finance combined account for nearly one-third of GDP; transportation and communication, public utilities, and construction account for one-fifth, and mining and manufacturing constitute nearly another fifth.[13]Netofficial development assistanceto Jordan in 2009 totalled US$761 million; according to the government, approximately two-thirds of this was allocated as grants, of which half was direct budget support.[182]

The official currency is theJordanian dinar,which is pegged to the International Monetary Fund'sspecial drawing rights,equivalent to an exchange rate of1 US$ ≡0.709 dinar, or approximately1 dinar ≡1.41044 dollars.[183]In 2000, Jordan joined theWorld Trade Organizationand signed theJordan–United States Free Trade Agreement,thus becoming the first Arab country to establish a free trade agreement with the United States. Jordan enjoys advanced status with the EU, which has facilitated greater access to export to European markets.[184]Due to slow domestic growth, high energy and food subsidies and a bloatedpublic-sectorworkforce, Jordan usually runs annualbudget deficits.[185]

TheGreat Recessionand the turmoil caused by theArab Springhave depressed GDP growth, damaging trade, industry, construction and tourism.[14]Tourist arrivals have dropped sharply since 2011.[186]Since 2011, thenatural gas pipelineinSinaisupplying Jordan from Egypt was attacked 32 times by Islamic State affiliates. Jordan incurred billions of dollars in losses because it had to substitute more expensive heavy-fuel oils to generate electricity.[187]In 2012, the government cut subsidies on fuel, increasing its price.[188]The decision, which was later revoked, caused large scale protests to break out across the country.[185][186]

Foreign debt in 2011 was $19 billion, representing 60% of its GDP. In 2016, the debt reached $35.1 billion representing 93% of its GDP.[110]This substantial increase is attributed to effects of regional instability causing a decrease in tourist activity, decreased foreign investments, increased military expenditures, attacks on Egyptian pipelines, the collapse of trade with Iraq and Syria, expenses from hosting Syrian refugees, and accumulated interest from loans.[110]According to the World Bank, Syrian refugees have cost Jordan more than $2.5 billion per year, amounting to 6% of the GDP and 25% of the government's annual revenue.[189]Foreign aid covers only a small part of these costs, 63% of the total costs are covered by Jordan.[190]An austerity programme was adopted by the government which aims to reduce thedebt-to-GDP ratioto 77 percent by 2021.[191]The programme succeeded in preventing the debt from rising above 95% in 2018.[192]

The proportion of well-educated and skilled workers is among the highest in the region in sectors such as ICT and industry, due to a relatively modern educational system. This has attracted large foreign investments and has enabled the country to export its workforce toPersian Gulf countries.[11]Flows ofremittancesgrew rapidly, particularly during the end of the 1970s and 1980s, and remains an important source of external funding.[193]Remittances were $3.8 billion in 2015, a notable rise compared to 2014 where remittances reached over $3.66 billion, making Jordan the fourth-largest recipient in the region.[194]

Transportation

Jordan is ranked as having the 35th best infrastructure in the world, one of the highest rankings in the developing world, according to the 2010 World Economic Forum's Index of Economic Competitiveness. This high infrastructural development is necessitated by its role as a transit country for goods and services mainly to Palestine and Iraq.[195]

According to data from the Ministry of Public Works and Housing, as of 2011[update],the road network consisted of 2,878 km (1,788 mi) of main roads; 2,592 km (1,611 mi) of rural roads and 1,733 km (1,077 mi) of side roads. TheHejaz railway,built during the Ottoman Empire which extended from Damascus to Mecca, will act as a base for future railway expansion plans. Currently, the railway has little civilian activity; it is primarily used for transporting goods. A national railway project is currently undergoing studies and seeking funding sources.[196]Amman has a network of public transportation buses including theAmman Busand theAmman Bus Rapid Transitand is connected to nearbyZarqathrough theAmman-Zarqa Bus Rapid Transit.

Jordan has three commercial airports, all receiving and dispatching international flights. Two are in Amman and the third is in Aqaba,King Hussein International Airport.Amman Civil Airportserves several regional routes and charter flights whileQueen Alia International Airportis the major international airport in Jordan and is thehubforRoyal Jordanian Airlines,theflag carrier.Queen Alia International Airport expansion was completed in 2013 with new terminals costing $700 million, to handle over 16 million passengers annually.[197]It is considered a state-of-the-art airport and was awarded 'the best airport by region: Middle East' for 2014 and 2015 byAirport Service Qualitysurvey, the world's leading airport passenger satisfaction benchmark programme.[198]

ThePort of Aqabais the only port in Jordan. In 2006, the port was ranked as being the "Best Container Terminal" in the Middle East byLloyd's List.The port was chosen because it a port for other neighbouring countries, its location is between four countries and three continents, it is an exclusive gateway for the local market, and it has been recenelty improved.[199]

Tourism

The tourism sector is considered a cornerstone of the economy and is a large source of employment, hard currency, and economic growth. In 2010, there were 8 million visitors to Jordan. The majority of tourists are from European and Arab countries.[12]Tourism has been severely affected by regional turbulence,[200]with the caused by the Arab Spring. Jordan experienced a 70% decrease in the number of tourists from 2010 to 2016;[201]tourist numbers started to recover in 2017.[201]

According to theMinistry of Tourism and Antiquities,Jordan is home to around 100,000 archaeological and tourist sites.[202]Some very well preserved historical cities includePetraandJerash,the former being the most popular tourist attraction and an icon of the kingdom.[201]As part of theHoly Land,there are numerous biblical sites, including:Al-Maghtas(a traditional location for theBaptism of Jesus),Mount Nebo,Umm ar-Rasas,MadabaandMachaerus.[203]Islamic sites include shrines of the prophetMuhammad's companions such asAbd Allah ibn Rawahah,Zayd ibn HarithahandMuadh ibn Jabal.[204]Ajloun Castle,built by Muslim Ayyubid leaderSaladinin the 12th century during his wars with the Crusaders, is also a popular tourist attraction.[116]

Modern entertainment, recreation and souqs in urban areas, mostly in Amman, also attract tourists. Recently, the nightlife in Amman, Aqaba and Irbid has started to emerge and the number of bars, discos and nightclubs is on the rise.[205]Alcohol is widely available in tourist restaurants, liquor stores and even some supermarkets.[206]Valleys includingWadi Mujiband hiking trails in different parts of the country attract adventurers. Hiking gaining popularity among tourists and locals. Places such as Dana Biosphere Reserve and Petra offer numerous signposted hiking trails. TheJordan Trail,a 650 km (400 mi) hiking trail stretching the entire country from north to south, crossing several attractions was established in 2015.[207]The trail aims to revive the tourism sector.[207]Moreover, seaside recreation is present on the shores of Aqaba and the Dead Sea through several international resorts.[208]

Jordan has been amedical tourismdestination in the Middle East since the 1970s. A study conducted byJordan's Private Hospitals Associationfound that 250,000 patients from 102 countries received treatment in Jordan in 2010, compared to 190,000 in 2007, bringing over $1 billion in revenue. Jordan is the region's top medical tourism destination, as rated by the World Bank, and fifth in the world overall.[209]The majority of patients come from Yemen, Libya and Syria because of the ongoing civil wars in those countries. Doctors and medical staff have gained experience in dealing with war patients through years of receiving such cases from various conflict zones in the region.[210]

Natural treatment methods can be found in bothMa'in Hot Springsand the Dead Sea. The Dead Sea is often described as a 'natural spa'. It contains 10 times more salt than the average ocean, which makes it impossible to sink in. The high salinity of the Dead Sea has been proven therapeutic for many skin diseases.[211]The uniqueness of this lake attracts several Jordanian and foreign vacationers, which boosted investments in the hotel sector in the area.[212]

Natural resources

Jordan is among the most water-scarce nations on Earth. At 97 cubic metres of water per person per year, it is considered to face "absolutewater scarcity"according to the Falkenmark Classification.[213]Scarce resources to begin with have been aggravated by the massive influx of Syrian refugees, many of whom face issues of access to clean water in informal settlements (see "Immigrants and Refugees" below).[214]Jordan shares both of its two main surface water resources, the Jordan and Yarmuk rivers, with neighbouring countries, adding complexity to water allocation decisions.[213]Water fromDisi aquiferand ten major dams historically played a large role in providing fresh water.[215]TheJawa Damin northeastern Jordan, which dates back to the fourth millennium BC, is the world's oldest dam.[216]

Natural gas was discovered in 1987; however, the estimated size of the reserve discovered was about 230 billioncubic feet,a minuscule quantity compared with its oil-rich neighbours. The Risha field, in the eastern desert beside the Iraqi border, produces nearly 35 million cubic feet of gas per day, which is sent to a nearby power plant to generate a small amount of Jordan's electricity needs.[217]This led to a reliance on importing oil to generate almost all of its electricity. Regional instability over the decades halted oil and gas supply to the kingdom from various sources, making it incur billions of dollars in losses. Jordan built aliquified natural gasport in Aqaba in 2012 to temporarily substitute the supply, while formulating a strategy to rationalize energy consumption and to diversify its energy sources.

Jordan receives 330 days of sunshine per year, and wind speeds reach over 7 m/s in the mountainous areas, so renewables proved a promising sector.[218]King Abdullah inaugurated large-scale renewable energy projects in the 2010s including the 117 MWTafila Wind Farm,the 53 MWShams Ma'an,and the 103 MWQuweirasolar power plants, with several more projects planned. By early 2019, it was reported that more than 1090 MW of renewable energy projects had been completed, contributing to 8% of Jordan's electricity up from 3% in 2011, while 92% was generated from gas.[219]After having initially set the percentage of renewable energy, Jordan aimed to generate by 2020 at 10%, the government announced in 2018 that it sought to beat that figure and aim for 20%.[220]

Jordan has the fifth largestoil-shalereserves in the world, which could be commercially exploited in the central and northwestern regions.[221]Official figures estimate reserves at more than 70 billion tonnes.Attarat Power Plant,its first oil-shale power plant, was commissioned 2023, with a 470 MW capacity.[222]Jordan also aims to benefit from its large uranium reserves by tapping nuclear energy. The original plan involved constructing two 1,000 MW reactors but has been scrapped because of financial constraints.[223]Currently, theAtomic Energy Commissionis considering buildingsmall modular reactorsinstead, whose capacities hover below 500 MW and can provide water sources throughdesalination.In 2018, the commission announced that Jordan was in talks with multiple companies to build its first commercial nuclear plant, a helium-cooled reactor that is scheduled for completion by 2025.[224]Phosphatemines in the south have made Jordan one of the largest producers and exporters of the mineral in the world.[225]

Industry

The industrial sector, which includes mining, manufacturing, construction, and power, accounted for approximately 26% of the GDP in 2004 (including manufacturing, 16.2%; construction, 4.6%; and mining, 3.1%). More than 21% of the labor force was employed in industry in 2002. In 2014, industry accounted for 6% of the GDP.[226]The main industrial products are potash, phosphates, cement, clothes, and fertilisers. The most promising segment of this sector is construction. Petra Engineering Industries Company, which is considered to be one of the main pillars of Jordanian industry, has gained international recognition with its air-conditioning units reachingNASA.[227]Jordan is now considered to be a leading pharmaceuticals manufacturer in theMENAregion led byHikma.[228]

The military industry thrived after theJordan Design and Development Bureaudefence company was established by King Abdullah II in 1999, to provide an indigenous capability for the supply of scientific and technical services to the Jordanian Armed Forces, and to become a global hub in security research and development. It manufactures all types of military products, many of which are presented at the bi-annually held international military exhibitionSOFEX.In 2015, the company exported $72 million worth of industries to over 42 countries.[229]

Science and technology

Science and technology is the fastest developing economic sector. This growth is occurring across multiple industries, including information and communications technology (ICT) and nuclear technology. Jordan contributes 75% of the Arabic content on the Internet.[231]In 2014, the ICT sector accounted for more than 84,000 jobs and contributed to 12% of the GDP. More than 400 companies are active in telecom, information technology, and video game development. 600 companies are operating in active technologies and 300 start-up companies.[231]Jordan was ranked 71st in theGlobal Innovation Indexin 2023, up from 86th in 2019.[232][233]

Nuclear science and technology are also expanding. TheJordan Research and Training Reactor,which was commissioned in 2016, is a 5 MW training reactor located at theJordan University of Science and TechnologyinAr Ramtha.[234]The facility is the first nuclear reactor in the country and will provide Jordan with radioactive isotopes for medical usage and provide training to students to produce a skilled workforce for the country's planned commercial nuclear reactors.[234]

Jordan also hosts theSynchrotron-Light for Experimental Science and Applications in the Middle East(SESAME) facility, which is the only particle accelerator in the Middle East, and one of only 60synchrotronradiation facilities in the world.[235]SESAME, supported byUNESCOandCERN,was opened in 2017 and allows for collaboration between scientists from various rival Middle Eastern countries.[235]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 200,000 | — |

| 1922 | 225,000 | +6.07% |

| 1948 | 400,000 | +2.24% |

| 1952 | 586,200 | +10.03% |

| 1961 | 900,800 | +4.89% |

| 1979 | 2,133,000 | +4.91% |

| 1994 | 4,139,500 | +4.52% |

| 2004 | 5,100,000 | +2.11% |

| 2015 | 9,531,712 | +5.85% |

| 2018 | 10,171,480 | +2.19% |

| Source: Department of Statistics[236] | ||

The 2015 census showed a population of 9,531,712 (female: 47%; males: 53%). Around 2.9 million (30%) were non-citizens, a figure including refugees and illegal immigrants.[4]There were 1,977,534 households in 2015, with an average of 4.8 persons per household (compared to 6.7 persons per household for the census of 1979).[4]Amman is one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities and one of the most modern in the Arab world.[237]The population of Amman was 65,754 in 1946, but exceeded 4 million by 2015.

Arabsmake up about 98% of the population. The remaining 2% consist largely of peoples from the Caucasus includingCircassians,Armenians,andChechens,along with smaller minority groups.[14]About 84.1% of the population live in urban areas.[14]

Refugees, immigrants and expatriates

Jordan was home to 2,175,491 Palestinian refugees as of December 2016; most of them had been granted Jordanian citizenship.[238]The first wave of Palestinian refugees arrived during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and peaked in the 1967 Six-Day War and the 1990 Gulf War. In the past, Jordan had given many Palestinian refugees citizenship, however recently citizenship is given only in rare cases. 370,000 of these Palestinians live in UNRWA refugee camps.[238]Following the capture of the West Bank by Israel in 1967, Jordan revoked the citizenship of thousands of Palestinians to thwart any attempt to permanently resettle from the West Bank to Jordan. West Bank Palestinians with family in Jordan or Jordanian citizenship were issued yellow cards guaranteeing them all the rights of citizenship if requested.[239]

Up to 1,000,000Iraqismoved to Jordan following the Iraq War in 2003,[240]and most of them returned; by 2015 their number was 130,911. Many Iraqi Christians (Assyrians/Chaldeans) however settled temporarily or permanently in Jordan.[241]Immigrants also include 15,000 Lebanese who arrived following the2006 Lebanon War.[242]Since 2010, over 1.4 millionSyrian refugeeshave fled to Jordan to escape the violence in Syria,[4]the largest population being in theZaatari refugee camp.The kingdom has continued to demonstrate hospitality, despite the substantial strain the flux of Syrian refugees places on Jordanian communities, as the vast majority of Syrian refugees do not live in camps. The refugee crisis effects include competition for job opportunities, water resources and other state provided services, along with the strain on the national infrastructure.[10]

In 2007 there were up to 150,000AssyrianChristians;most areEastern Aramaicspeaking refugees from Iraq.[243]Kurdsnumber some 30,000, and like the Assyrians, many are refugees from Iraq, Iran and Turkey.[244]Descendants ofArmeniansthat sought refuge in the Levant during the 1915Armenian genocidenumber approximately 5,000 persons, mainly residing in Amman.[245]A small number of ethnicMandeansalso reside in Jordan, again mainly refugees from Iraq.[246]Around 12,000Iraqi Christianshave sought refuge in Jordan after the Islamic State took the city ofMosulin 2014.[247]Several thousand Libyans, Yemenis and Sudanese have also sought asylum to escape instability and violence in their respective countries.[10]The 2015 census recorded 1,265,000 Syrians, 636,270 Egyptians, 634,182 Palestinians, 130,911 Iraqis, 31,163 Yemenis, 22,700 Libyans and 197,385 from other nationalities residing in the country.[4]

There are around 1.2 million illegal and 500,000 legal migrant workers and expatriates in the kingdom.[248]Thousands of foreign women, mostly from the Middle East and Eastern Europe, work in nightclubs, hotels and bars across the kingdom.[249][250][251]American and European expatriate communities are concentrated in the capital, as the city is home to many international organisations and diplomatic missions.[206]

Religion

Sunni Islamis the dominant religion. Muslims make up about 95% of the population; in turn, 93% of those self-identify as Sunnis.[252]There are also a small number ofAhmadiMuslims[253]and someShiites.Many Shia are Iraqi and Lebanese refugees.[254]Muslims who convert to another religion as well as missionaries from other religions face societal and legal discrimination.[255]

Jordan contains some of theoldest Christian communitiesin the world, dating as early as the 1st century AD after thecrucifixion of Jesus.[256]Christians today make up about 4% of the population,[257]down from 20% in 1930, though their absolute number has grown.[258]This is due to high immigration rates of Muslims into Jordan, higher emigration rates of Christians to theWest,and higher birth rates for Muslims.[259]Christians number around 250,000, all of whom are Arabic-speaking, according to a 2014 estimate by the Orthodox Church, though the study excluded minority Christian groups and the thousands of Western, Iraqi and Syrian Christians residing in Jordan.[257]Christians are well integrated in society and enjoy a high level of freedom.[260]Christians are also influential in the media.[261]

Smaller religious minorities includeDruze,BaháʼísandMandaeans.Most Druze live in Azraq, some villages on the Syrian border, and in Zarqa, while most Jordanian Baháʼís live in Adassiyeh bordering the Jordan Valley.[262]It is estimated that 1,400 Mandaeans live in Amman; they came from Iraq after the 2003 invasion fleeing persecution.[263]

Languages

The official language isModern Standard Arabic,a literary language taught in the schools.[264]Most Jordanians natively speak one of the non-standard Arabic dialects known asJordanian Arabic.Jordanian Sign Languageis the language of the deaf community. English, though without official status, is widely spoken throughout the country and is thede factolanguage of commerce and banking, as well as a co-official status in the education sector; almost all university-level classes are held in English, and almost all public schools teach English along with Standard Arabic.[264]Chechen,Circassian,Armenian,Tagalog,andRussianare popular among their communities.[265]Frenchis offered as an elective in many schools, mainly in the private sector.[264]Germanis an increasingly popular language; it has been introduced at a larger scale since the establishment of theGerman Jordanian Universityin 2005.[266]

Health and education

Life expectancy was around 74.8 years in 2017.[14]The leading cause of death is cardiovascular diseases, followed by cancer.[268]Childhood immunization rates have increased steadily over the past 15 years; by 2002 immunisations andvaccinesreached more than 95% of children under five.[269]In 1950,water and sanitationwas available to only 10% of the population; in 2015, it reached 98% of Jordanians.[270]

Health services are some of the best in the region.[271]Qualified medics, a favourable investment climate, and ecomonic stability hasave contributed to the success of this sector.[272]The health care system is divided between public and private institutions. On 1 June 2007,Jordan Hospital(as the biggest private hospital) was the first general specialty hospital to gain the international accreditationJCAHO.[269]TheKing Hussein Cancer Centeris a leading cancer treatment centre.[273]66% of Jordanians have medical insurance.[4]

The educational system comprises 2 years of pre-school education, 10 years of compulsory basic education, and two years of secondary academic or vocational education, after which the students sit for the General Certificate of Secondary Education Exam (Tawjihi)exams.[274]Primary education is free.[275]Scholars may attend either private or public schools. According to theUNESCO,the literacy rate in 2015 was 98.01% and is considered to be the highest in the Middle East and the Arab world, and one of the highest in the world.[267]UNESCO ranked Jordan's educational system 18th out of 94 nations for providing gender equality in education.[276]Jordan has the highest number of researchers in research and development per million people among all the 57 countries that are members of theOrganisation of Islamic Cooperation.There are 8,060 researchers per million people, while the world average is 2,532 per million.[277]

Jordan has 10 public universities, 19 private universities and 54 community colleges, of which 14 are public, 24 private and others affiliated with the Jordanian Armed Forces, the Civil Defense Department, the Ministry of Health and UNRWA.[278]There are over 200,000 students enrolled in universities each year. An additional 20,000 pursue higher education abroad primarily in the United States and Europe.[279]According to theWebometrics Ranking of World Universities,the top-ranking universities in the country are theUniversity of Jordan(UJ) (1,220th worldwide),Jordan University of Science & Technology(JUST) (1,729th) andHashemite University(2,176th).[280]UJ and JUST occupy 8th and 10th between Arab universities.[281]

Culture

Art and museums

Many institutions aim to increase cultural awareness ofJordanian artand to represent artistic movements in fields such as paintings, sculpture, graffiti and photography.[282]The art scene has been developing in the past few years,[283]and Jordan has been a haven for artists from surrounding countries.[284]In January 2016, for the first time ever, aJordanian filmcalledTheebwas nominated for theAcademy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film.[285]

The largest museum isThe Jordan Museum.It contains much of the valuable archaeological findings in the country, including some of theDead Sea Scrolls,the Neolithic limestone statues of'Ain Ghazaland a copy of theMesha Stele.[286]Most museums are located in Amman includingThe Children's Museum Jordan,The Martyr's Memorial and Museumand theRoyal Automobile Museum.Museums outside Amman include theAqaba Archaeological Museum.[287]TheJordan National Gallery of Fine Artsis a major contemporary art museum located in Amman.[287]

Music in Jordanis developing a lot of new bands and artists who are popular in the Middle East. Artists such asOmar Al-Abdallat,Toni Qattan,Diana KarazonandHani Mitwasihave increased the popularity of Jordanian music.[288]TheJerash Festivalis an annual music event that features popular Arab singers.[288]Pianist and composerZade Diranihas gained wide international popularity.[289]There is also an increasing growth of alternativeArabic rockbands, who are dominating the scene in the Arab world, including:El Morabba3,Autostrad,JadaL,Akher ZapheerandAziz Maraka.[290]

Jordan unveiled its first underwater military museum off the coast of Aqaba. Several military vehicles, including tanks, troop carriers and a helicopter are in the museum.[291]

Cuisine

As the eighth-largest producer ofolivesin the world,olive oilis the main cooking oil in Jordan.[292]A common appetizer ishummus,which is a puree ofchickpeasblended withtahini,lemon, and garlic.Ful medamesis another well-known appetiser. A typical worker's meal, it has since made its way to the tables of the upper class. A typicalmezeoften containskoubba maqliya,labaneh,baba ghanoush,tabbouleh,olivesandpickles.[293]Meze is generally accompanied by the Levantine alcoholic drinkarak,which is made from grapes and aniseed and is similar toouzo,rakıandpastis.Jordanian wineandbeerare also sometimes used. The same dishes, served without alcoholic drinks, can also be termed "muqabbilat" (starters) in Arabic.[206]

The most distinctive dish ismansaf,the national dish of Jordan. The dish is a symbol for hospitality and is influenced by the Bedouin culture. Mansaf is eaten on different occasions such as funerals, weddings and on religious holidays. It consists of a plate of rice with meat that was boiled in thick yogurt, sprinkled with pine nuts and sometimes herbs. As an old tradition, the dish is eaten using one's hands, but the tradition is not always used.[293]Simple fresh fruit is often served towards the end of a meal, but there is also dessert, such asbaklava,hareeseh,knafeh,halvaandqatayef,a dish made specially forRamadan.Drinking coffee and tea flavoured withna'naormeramiyyehis commonplace.[294]

Sports

While both team and individual sports are widely played, the kingdom has enjoyed its biggest international achievements intaekwondo.The highlight came at the2016 Rio Olympic GameswhenAhmad Abughaushwon Jordan's first ever medal[295]of any colour at the games by taking gold in the −67 kg weight.[296]Medals have continued to be won at world and Asian level in the sport since to establish taekwondo as the kingdom's favourite sport alongsidefootball[206]andbasketball.[297]

Football is the most popular sport.[298]Thenational football teamcame within a play-off of reaching the2014 FIFA World CupinBrazil,[299]but lost thetwo-legged tieagainstUruguay.[300]They previously reached the quarter-finals of theAFC Asian Cupin2004and2011,and lost in thefinalagainstQatarin2023.[301]

Jordan has a strong policy for inclusive sport and invests heavily in encouraging girls and women to participate in all sports. Thewomen's football teamgaining reputation,[302]and in March 2016 ranked 58th in the world.[303]In 2016, Jordan hosted theFIFA U-17 Women's World Cup,with 16 teams representing six continents. The tournament was held in four stadiums in the three Jordanian cities of Amman, Zarqa and Irbid. It was the first women's sports tournament in the Middle East.[304]

Basketball is another sport that Jordan continues to excel in, having qualified to theFIBA 2010 World Basketball Cupand more recently reaching the2019 World Cup in China.[305]Jordan came within a point of reaching the2012 Olympicsafter losing the final of the 2010 Asian Cup to China, 70–69, and settling for silver instead. Thenational basketball teamparticipates in various international and Middle Eastern tournaments. Local basketball teams include: Al-Orthodoxi Club, Al-Riyadi, Zain, Al-Hussein and Al-Jazeera.[306]

Boxing,karate,kickboxing,Muay Thai,andju-jitsuare also popular. Less common sports are also gaining popularity.Rugbyis increasing in popularity, a rugby union is recognized by the Jordan Olympic Committee which supervises three national teams.[307]Althoughcyclingis not widespread, the sport is developing as a lifestyle and a new way to travel especially among the youth.[308]In 2014, a NGOMake Life Skate Lifecompleted construction of the7Hills Skatepark,the first skatepark in the country located inDowntown Amman.[309]

See also

Notes

- ^Arabic:الأردن,romanized:al-Urdun[al.ʔʊr.dʊn]

- ^Arabic:المملكة الأردنية الهاشمية,romanized:al-Mamlaka al-Urduniyya al-Hāshimiyya

- ^The country became officially known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in Arabic; however, it continued to be referred to as the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan in English until 1949.

References

- ^Temperman, Jeroen (2010).State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law: Towards a Right to Religiously Neutral Governance.Brill. p. 87.ISBN978-90-04-18148-9.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2017.Retrieved12 June2018.

- ^"Jordanian Constitution".Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Constitutional Court.Archivedfrom the original on 12 August 2020.Retrieved31 August2020.

- ^"Population clock".Jordan Department of Statistics.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2019.Retrieved1 October2023.

- ^abcdefgGhazal, Mohammad (22 January 2016)."Population stands at around 9.5 million, including 2.9 million guests".The Jordan Times.Archivedfrom the original on 8 February 2018.Retrieved12 June2018.

- ^abcde"World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Jordan)".International Monetary Fund.10 October 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 30 October 2023.Retrieved14 October2023.

- ^"Gini index".World Bank.Archivedfrom the original on 9 February 2015.Retrieved12 June2018.

- ^"Human Development Report 2023/24"(PDF).United Nations Development Programme.13 March 2024.Archived(PDF)from the original on 13 March 2024.Retrieved13 March2024.

- ^"The Politics of Aid to Iraqi Refugees in Jordan".MERIP.20 September 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2022.Retrieved5 April2022.

- ^Frelick, Bill (27 November 2006).""The Silent Treatment": Fleeing Iraq, Surviving in Jordan ".Human Rights Watch.Archivedfrom the original on 5 April 2022.Retrieved5 April2022.

- ^abc"2015 UNHCR country operations profile – Jordan".UNHCR. Archived fromthe originalon 2 October 2014.Retrieved12 October2015.

- ^abEl-Said, Hamed; Becker, Kip (11 January 2013).Management and International Business Issues in Jordan.Routledge. p. 88.ISBN9781136396366.Archivedfrom the original on 28 November 2016.Retrieved15 June2016.

- ^ab"Jordan second top Arab destination to German tourists".Petra. Jordan News. 11 March 2016. Archived fromthe originalon 12 March 2016.Retrieved12 March2016.

- ^ab"Jordan's Economy Surprises".Washington Institute.29 June 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 10 October 2017.Retrieved9 April2016.

- ^abcdefghijk"The World Fact book – Jordan".CIA World Factbook.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2023.Retrieved15 June2018.

- ^abcMills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (1990).Mercer Dictionary of the Bible.Mercer University Press. pp. 466–467, 928.ISBN9780865543737.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2017.Retrieved15 June2018.

- ^abLe Strange, Guy (1890).Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A. D. 650 To 1500.Alexander P. Watt for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p.52.Archivedfrom the original on 5 October 2010.Retrieved15 June2018.

- ^Nicolle, David (1 November 2008).Crusader Warfare: Muslims, Mongols and the struggle against the Crusades.Hambledon Continuum. p. 118.ISBN9781847251466.Archivedfrom the original on 10 April 2023.Retrieved15 June2018.

- ^Patai, Raphael (8 December 2015).Kingdom of Jordan.Princeton University Press. pp. 23, 32.ISBN9781400877997.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2017.Retrieved16 June2018.

- ^abal-Nahar, Maysoun (11 June 2014)."The First Traces of Man. The Palaeolithic Period (<1.5 million – ca 20,000 years ago)".In Ababsa, Myriam (ed.).Atlas of Jordan.Contemporain publications. Presses de l'Ifpo. pp. 94–99.ISBN9782351594384.Archivedfrom the original on 15 June 2018.Retrieved16 June2018.

- ^Abu-Jaber, Nizar; Al Khasawneh, Sahar; Alqudah, Mohammad; Hamarneh, Catreena; Al-Rawabdeh, Abdulla; Murray, Andrew (1 November 2020)."Lake Elji and a geological perspective on the evolution of Petra, Jordan".Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology.557:109904.Bibcode:2020PPP...55709904A.doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109904.ISSN0031-0182.S2CID225003090.Retrieved6 December2022.