Jutland

Jutland(Danish:Jylland[ˈjyˌlænˀ],Jyske HalvøorCimbriske Halvø;German:Jütland,Kimbrische HalbinselorJütische Halbinsel) is a peninsula ofNorthern Europethat forms the continental portion ofDenmarkand part of northernGermany(Schleswig-Holstein). It stretches from theGrenenspit in the north to the confluence of theElbeand theSudein the southeast. The historic southern border river of Jutland as a cultural-geographical region, which historically also includedSouthern Schleswig,is theEider.The peninsula, on the other hand, also comprises areas south of theEider:Holstein,theformer duchyofLauenburg,and most ofHamburgandLübeck.

Jutland's geography is flat, with comparatively steep hills in the east and a barely noticeable ridge running through the center. West Jutland is characterised by open lands,heaths,plains, andpeatbogs,while East Jutland is more fertile with lakes and lush forests. The southwestern coast is characterised by theWadden Sea,a large unique international coastal region stretching through Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands. The peninsula's longest river is theEider,that rises close to the Baltic but flows in the direction of the North Sea due to a moraine, while theGudenåis the longest river of Denmark. In order for ships not having to go around the whole peninsula to reach the Baltic, theKiel Canal,the world's busiest artificial waterway, that crosses the peninsula in the south, has been constructed. Jutland is connected toFunenby theOldandNew Little Belt Bridge,and Funen in turn is connected toZealandandCopenhagenby theGreat Belt Bridge.

Etymology[edit]

Jutland is known by several different names, depending on the language and era, includingGerman:Jütland[ˈjyːtlant];Old English:Ēota land[ˈeːotɑˌlɑnd],known anciently as the Cimbric Peninsula or Cimbrian Peninsula (Latin:Cimbricus Chersonesus;Danish:den Cimbriske Halvøorden Jyske Halvø;German:Kimbrische HalbinselorJütische Halbinsel). The names are derived from theJutesand theCimbri,respectively.

Geography[edit]

Distinction between the Jutland peninsula and Jutland[edit]

The Jutland peninsula reaches from the sandbar spit ofGrenenon theNorth Jutlandic Islandin the north, to the banks of theElbein the south. The peninsula is also called theCimbric peninsula.

Jutland as a cultural-geographical term mostly only refers to the Danish part of the peninsula, fromGrenento the Danish-German border. Sometimes, the northern part ofSchleswig-Holsteindown to theEider(Southern Schleswig), is also included in the cultural-geographical definition of Jutland, because the Eider was historically the southern border of Denmark and the cultural and linguistic boundary between theNordic countriesand Germany fromc.850 to 1864.

In Denmark, the termJyllandcan refer both to the whole peninsula and to the region between Grenen and either the Danish-German border or the Eider.

In Germany, however, the peninsula as a whole is only referred to asKimbrische HalbinselorJütische Halbinsel,while the termJütlandis reserved solely for the cultural-geographical definition of Jutland.

Maritime border[edit]

The Jutlandpeninsulais bounded by theNorth Seato the west, theSkagerrakto the north, theKattegatto the northeast, and theBaltic Seato the southeast. The peninsula's Kattegat and Baltic coastline stretches fromGrenendown to the mouth of theTraveinLübeck-Travemünde,and its Skagerrak and North Sea coastline runs from Grenen until down to theGeesthachtbarrage east ofHamburg,which is defined as the point where theLower Elbe(Unterelbe) and the estuary of the Elbe, that are subject to the tides, begin. The part of the Baltic Sea the peninsula is bounded by is referred to asda:Bælthavetin Danish andde:Beltseein German, a designation deriving from theGreat,Little,andFehmarnbelts, while the Baltic Sea as a whole is calledØstersøenandOstsee,respectively.

Land border[edit]

The peninsula's land border in the southeast and south is constituted by a string of several rivers and lakes: from the mouth of theTraveatLübeck-Travemündeup to the mouth of theWakenitzinto the Trave (in Lübeck), from there up the Wakenitz until its outflow from lakeRatzeburger See,then through lake Kleiner Küchensee to the mouth of thede:Schaalseekanalinto lake Großer Küchensee, from there along the canal through lakes Salemer See, Pipersee and Phulsee to lakeSchaalsee,on fromZarrentin am Schaalseealong the outflow of lake Schaalsee, theSchaale,until its mouth into theSudeatTeldau,then along the Sude until its confluence with the Elbe atBoizenburg,and further on along the Elbe, until theGeesthachtbarrage east ofHamburg,where the tide-dependent estuary of the Elbe begins.

Travemünde→Trave→Wakenitz→Ratzeburger See→Kleiner Küchensee→Großer Küchensee→Schaalsee canal→Salemer See→Pipersee→Phulsee→Schaalsee→Schaale→Sude→ElbeatBoizenburg→beginning of the estuary of the Elbe at theGeesthachtbarrage

Subregions (from south to north)[edit]

Lauenburg[edit]

Lauenburg is the southeasternmost area ofSchleswig-Holstein.It exists administratively as the district ofHerzogtum Lauenburg(Duchy of Lauenburg), the surface of which is equal to the territory of the formerDuchy of Saxe-Lauenburg,which historically did not belong to Holstein. The Duchy of Lauenburg existed since 1296, and when it was absorbed by theKingdom of Prussiaand became part of the PrussianProvince of Schleswig-Holsteinin 1876, the new district was allowed to keep the name "duchy" in its name as a reminiscence to its ducal past, and today it is the only district in Germany with such a designation. The region is named for its former capital, the town ofLauenburg on the Elbe,but its seat is now atRatzeburg.Lauenburg is crossed by theElbe–Lübeck Canal,that connects the Elbe at Lauenburg to the Baltic at Lübeck, and there are over 50 lakes in the area, many of which are part of theLauenburg Lakes Nature Park.

Hamburg[edit]

Hamburg is its own city-state and does not belong to Schleswig-Holstein. The northelbishdistricts ofHamburgthat are on the Jutland peninsula are historically part of the region ofStormarn.The former border rivers of Stormarn are theStörandKrückauin the northwest, theTraveandBillein the east, and theElbein the south. There exists also adistrict of Stormarnnortheast of Hamburg in Schleswig-Holstein. But this district does not cover the entire area of the historic region of Stormarn, and while those parts of Stormarn now lying in Schleswig-Holstein are nowadays considered parts of Holstein, the areas of Stormarn today in the city-state of Hamburg, are not.

Holstein[edit]

The bulk of the southernmost areas of the Jutland peninsula belongs toHolstein,stretching from the Elbe in the south to theEiderin the north. Subregions of Holstein areDithmarschenon the North Sea side,Stormarnat the centre, andWagriaon the Baltic side. There is an area in Holstein calledHolstein Switzerlandbecause of its comparable higher hills. The largest amount of lakes on the Jutland peninsula can be found in Holstein, the ten largest lakes being theGroßer Plöner See(which is also the largest lake on the whole Jutland peninsula),Selenter See,Kellersee,Dieksee,Lanker See,Behler See,Postsee,Kleiner Plöner See,Großer Eutiner See,and the Stocksee. One of the world's most frequented artificial waterways, theKiel Canal,runs through the Jutland peninsula in Holstein, connecting the North Sea atBrunsbüttelto the Baltic atKiel-Holtenau.TheEideris the longest river of the Jutland peninsula. Holstein is one of the most populated subregions of the Jutland peninsula because of the densely populated area around Hamburg, which in large parts lies in Holstein.

Southern Schleswig[edit]

Between theEiderand the Danish-German border stretchesSouthern Schleswig.Notable subregions of Southern Schleswig are the peninsula ofEiderstedtandNorth Frisiaon the North Sea side, and the peninsulas ofDanish Wahld,Schwansen,andAngliaon the Baltic side. There is a considerable North Frisian minority inNorth Frisia,andNorth Frisianis an official language in the region. InAngliaandSchwansenon the other hand, there exist indigenous Danish minorities, with Danish being the second official language there. TheDanish Wahldonce formed a border forest between Danish and Saxon settlements. A system of Danish fortifications, theDanevirke,runs through Southern Schleswig, overcoming the drainage divide between Baltic (Schlei) and North Sea (Rheider Au). At the Baltic end of the Danevirke isHedeby,a former important Viking town.

Southern Jutland (Sønderjylland)[edit]

Between the Danish-German border and theKongeålies Southern Jutland (theSouth Jutland County), historically also known as Northern Schleswig. Northern and Southern Schleswig once formed the territory of the formerDuchy of Schleswig.The region is calledSønderjyllands Amtin Danish, and it is regarded as the northern part ofSønderjylland,which refers to the combined territory of Northern and Southern Schleswig.

Northern Jutland (Nørrejylland)[edit]

Northern Jutlandis the region between theKongeåand Jutland's northernmost point, theGrenenspit. In Danish, it is calledNørrejylland,and also encompasses theNorth Jutlandic Island(Danish:Nørrejyske ØorVendsyssel-Thy). Northern Jutland is traditionally subdivided into South Jutland (Sydjylland), West Jutland (Vestjylland), East Jutland (Østjylland), and North Jutland (Nordjylland). More recent is the designation Central Jutland (Midtjylland) for parts of traditionally West and East Jutish areas. Subregions of Northern Jutland include the peninsulas ofDjurslandwithMols,andSalling.Also in Northern Jutland is theSøhøjlandet,which is the highest elevated Danish region, and at the same time, the region with the highest density of lakes in Denmark. Denmark's longest river, theGudenå,flows through Northern Jutland.

South Jutland (Sydjylland)[edit]

South Jutland (Sydjylland) is the southernmost part of Northern Jutland. It is not to be confused with Southern Jutland (Sønderjylland), which is adjacent to South Jutland in the south. South Jutland stretches betweenSønderjyllandin the south, and the border between the two administrative regions ofSouthern DenmarkandCentral Jutlandin the north.

West Jutland (Vestjylland)[edit]

West Jutland (Vestjylland) is the central western part of Northern Jutland. It lies betweenBlåvandshukin the south, and theNissum Bredningin the north. It is north of South Jutland and west of East Jutland.

East Jutland (Østjylland)[edit]

East Jutland (Østjylland) is the central eastern part of Northern Jutland. It lies betweenSkærbækon theKolding Fjordin the south, and the end of theMariager Fjordin the north.Aarhus,the largest city completely on the Jutland peninsula, is in East Jutland.

Central Jutland (Midtjylland)[edit]

The concept of Central Jutland (Midtjylland) is of recent date, since a few decades ago it was usual to divide Northern Jutland into the traditional East and West Jutland (in addition to North and South Jutland), only. However, the term has been used in and aroundViborg,so that the people of Viborg could differentiate themselves from the populations to the east and west. The majority of what is today called Central Jutland is actually the traditional West Jutish culture and dialect area, i.e.Herning,Skive,Ikast,andBrande.By contrast,Silkeborgand the other areas east of the Jutish ridge are traditionally part of the East Jutish cultural area. A new meaning of Central Jutland is the entire area between North and South Jutland, corresponding roughly to theCentral Jutland Region.

North Jutland (Nordjylland)[edit]

While the term Northern Jutland (Danish:Nørrejylland) refers to the whole region betweenKongeåandGrenen,North Jutland (Danish:Nordjylland) only refers to the northernmost part of Northern Jutland, and encompasses the largest part ofHimmerland,the northernmost part of Crown Jutland (Kronjylland), the island ofMors(Morsø), and Jutland north of theLimfjord(theNorth Jutlandic Island,which is subdivided into the regions ofThy,Hanherred,andVendsyssel,the northernmost region of Jutland and Denmark).Nordjyllandis congruent with theNorth Jutland Region(Region Nordjylland).

Offshore Islands[edit]

The largest Kattegat and Baltic islands off Jutland areFunen,Als,Læsø,Samsø,andAnholtin Denmark, as well asFehmarnin Germany.

The islands ofLæsø,Anholt,andSamsøin theKattegat,andAlsat the rim of theBaltic Sea,are administratively and historically tied to Jutland, although the latter two are also regarded as traditional districts of their own. Inhabitants of Als, known asAlsinger,would agree to be South Jutlanders, but not necessarily Jutlanders.[citation needed]

The largest North Sea islands off the Jutish coast are theDanish Wadden Sea IslandsincludingRømø,Fanø,andMandøin Denmark, and theNorth Frisian IslandsincludingSylt,Föhr,AmrumandPellwormin Germany. On the German islands, someNorth Frisiandialects are still in use.

Human Geography[edit]

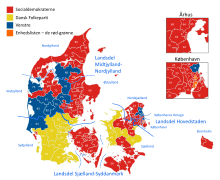

Administratively, the Jutland peninsula belongs to three German states and three Danish regions:

- most of the city-state ofHamburgexcept the boroughs south of theElbe

- almost the entire German state ofSchleswig-Holsteinexcept some parts of theHerzogtum Lauenburgdistrict east ofRatzeburger See,de:Schaalseekanal,andSchaalsee

- a very small part west of theSchaaleand north of theSudebelongs to the district ofLudwigslust-Parchimin the state ofMecklenburg-Vorpommern

- theRegion of Southern Denmark(Region Syddanmark) exceptFunenand the islands surrounding it

- theCentral Jutland Region(Region Midtjylland)

- theNorth Jutland Region(Region Nordjylland)[1]

Largest cities[edit]

The ten largest cities on the Jutland peninsula are:

- Hamburg(boroughs north of theElbe) 1,667,035

- Aarhus290,598

- Kiel247,717

- Lübeck218,095

- Aalborg120,914

- Flensburg92,550

- Norderstedt81,880

- Neumünster79,502

- Esbjerg71,921

- Randers64,057

Largest cities in the Danish part[edit]

- Aarhus290,598

- Aalborg120,914

- Esbjerg71,921

- Randers64,057

- Horsens63,162

- Kolding62,338

- Vejle61,310

- Herning51,193

- Silkeborg50,866

- Fredericia41,243

Aarhus,Silkeborg,Billund,Randers,Kolding,Horsens,Vejle,FredericiaandHaderslev,along with a number of smaller towns, make up the suggestedEast Jutland metropolitan area,which is more densely populated than the rest of Jutland, although far from forming one consistent city.

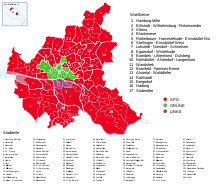

Largest cities in the German part[edit]

1.Hamburg(boroughs north of theElbe) 1,667,035

- Altona280,034,Bergedorf132,901,Eimsbüttel274,901,Hamburg-Nord322,564,Wandsbek453,086, and the quarters ofHamburg-Mittenorth of the Elbe:

2.Kiel247,717

3.Lübeck218,095

4.Flensburg92,550

5.Norderstedt81,880

6.Neumünster79,502

7.Elmshorn50,772

8.Pinneberg44,279

9.Wedel34,538

10.Ahrensburg34,509

Geology[edit]

This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(January 2017) |

Geologically,theMid Jutland Regionand theNorth Jutland Regionas well as theCapital Region of Denmarkare located in the north of Denmark which is rising because ofpost-glacial rebound.

Some circular depressions in Jutland may be remnants of collapsedpingosthat developed during theLast Ice Age.[2]

History[edit]

Jutland has historically been one of the threelands of Denmark,the other two beingScaniaandZealand.Before that, according toPtolemy,Jutland or theCimbric Chersonesewas the home ofTeutons,Cimbri,andCharudes.[citation needed]

ManyAngles,SaxonsandJutesmigrated fromContinental EuropetoGreat Britainstarting around 450 AD. The Angles gave their name to the new emerging kingdoms called England (i.e., "Angle-land" ). TheKingdom of Kentinsouth east Englandis associated with Jutish origins andmigration,also attributed byBedein theEcclesiastical History.[3]This is also supported by the archaeological record, with extensive Jutish finds inKentfrom thefifthandsixth centuries.[3]

Saxons andFrisiimigrated to the region in the early part of the Christian era. To protect themselves from invasion by the ChristianFrankishemperors, beginning in the5th century,thepaganDanes initiated theDanevirke,a defensive wall stretching from present-daySchleswigand inland halfway across the Jutland Peninsula.[citation needed]

The pagan Saxons inhabited the southernmost part of the peninsula, adjoining the Baltic Sea, until theSaxon Warsin 772–804 in theNordic Iron Age,whenCharlemagneviolently subdued them and forced them to be Christianised.Old Saxonywas politically absorbed into theCarolingian EmpireandAbodrites(orObotrites), a group ofWendishSlavswho pledged allegiance to Charlemagne and who had for the most partconverted to Christianity,were moved into the area to populate it.[4]Old Saxony was later referred to asHolstein.[citation needed]

In medieval times, Jutland was regulated by theLaw Code of Jutland(Jyske Lov). This civic code covered the Danish part of the Jutland Peninsula, i.e., north of theEider (river),Funenas well asFehmarn.Part of this area is now in Germany.[citation needed]

During the industrialisation of the 1800s, Jutland experienced a large and acceleratingurbanisationand many people from the countryside chose to emigrate. Among the reasons was a high and accelerating population growth; in the course of the century, the Danish population grew two and a half times to about 2.5 million in 1901, with a million people added in the last part of the 1800s. This growth was not caused by an increase in thefertility rate,but by better nutrition, sanitation, hygiene, and health care services. More children survived, and people lived longer and healthier lives. Combined with falling grain prices on the international markets because of theLong Depression,and better opportunities in the cities due to an increasing industrialisation, many people in the countryside relocated to larger towns or emigrated. In the later half of the century, around 300,000 Danes, mainly unskilled labourers from rural areas, emigrated to the US or Canada.[5]This amounted to more than 10% of the then total population, but some areas had an even higher emigration rate.[6][7]In 1850, the largest Jutland towns of Aalborg, Aarhus and Randers had no more than about 8,000 inhabitants each; by 1901, Aarhus had grown to 51,800 citizens.[8]

To speed transit between the Baltic and the North Sea, canals were built across the Jutland Peninsula, including theEider Canalin the late 18th century, and theKiel Canal,completed in 1895 and still in use.

In 1825, a severe North Sea storm on the west coast of Jutland breached the isthmus ofAgger Tangein theLimfjordarea, separating the northern part of Jutland from the mainland and effectively creating theNorth Jutlandic Island.The storm breach of Agger Tange created the Agger Channel, and another storm in 1862 created theThyborønChannel close by. The channels made it possible for ships to shortcut theSkagerrak Sea.The Agger Channel closed up again over the years, due to naturalsiltation,but the Thyborøn Channel widened and was fortified and secured in 1875.[9]

World War I and Battle of Jutland[edit]

Denmark was neutral during theFirst World War.However, an estimated 5,000 Danes living in North Slesvig were killed serving in the German army. The 1916Battle of Jutlandwas fought in the North Sea west of Jutland.[10]

World War II[edit]

Denmark had declared itself neutral, but was invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany within a few hours on 9 April 1940. Scattered fighting took place in South Jutland and in Copenhagen. Sixteen Danish soldiers were killed.[citation needed]

Some months before the invasion, Germany had considered only occupying the northern tip of Jutland with Aalborg airfield, but Jutland as a whole was soon regarded as of high strategic importance. Work commenced on extending theAtlantic Wallalong the entire west coast of the peninsula. Its task was to resist a potential allied attack on Germany by landing on the west coast of Jutland. TheHanstholmfortress at the northwestern promontory of Jutland became the largest fortification of Northern Europe. The local villagers were evacuated toHirtshals.Coastal areas of Jutland were declared a military zone where Danish citizens were required to carry identity cards, and access was regulated.[citation needed]

The small Danish airfield of Aalborg was seized as one of the first objects in the invasion by German paratroopers. The airfield was significantly expanded by the Germans in order to secure their traffic to Norway, and more airfields were built. Danish contractors and 50,000–100,000 workers were hired to fulfill the German projects. The alternative for workers was to be unemployed or sent to work in Germany. The fortifications have been estimated to be the largest construction project ever performed in Denmark at a cost of then 10 billion kroner, or 300-400 billion DKK today (45-60 billion USD or 40-54 billion euro in 2019). The Danish National Bank was forced to cover most of the cost.[11]After the war, the remaining German prisoners of war were recruited to perform extensivemine clearanceof 1.4 million mines along the coast.[citation needed]

Many of the seaside bunkers from World War II are still present at the west coast. Several of the fortifications in Denmark have been turned into museums, includingTirpitz Museumin Blåvand,Bunkermuseum Hanstholm,andHirtshals Bunkermuseum.

In Southern Jutland, parts of theGerman minorityopenly sided with Germany and volunteered for German military service. While some Danes initially feared a border revision, the German occupational force did not pursue the issue. In a judicial aftermath after the end of the war, many members of the German minority were convicted, and German schools were confiscated by Danish authorities.[citation needed]There were some instances of Danish mob attacks against German-minded citizens.[citation needed]In December 1945, the remaining part of the German minority issued a declaration of loyalty to Denmark and democracy, renouncing any demands for a border revision.[citation needed]

Culture[edit]

Up until theindustrialisationof the 19th century, most people in Jutland lived a rural life as farmers and fishers. Farming and herding have formed a significant part of the culture since the lateNeolithic Stone Age,and fishing ever since humans first populated the peninsula after the last Ice Age, some 12,000 years ago.[citation needed]

The local culture of Jutland commoners before industrial times was not described in much detail by contemporary texts. It was generally viewed with contempt by the Danish cultural elite in Copenhagen who perceived it as uncultivated, misguided or useless.[12]

While the peasantry of eastern Denmark was dominated by the upperfeudal class,manifested in large estates owned by families ofnoble birthand an increasingly subdued class of peasant tenants, the farmers of Western Jutland were mostly free owners of their own land or leasing it from the Crown, although under frugal conditions.[citation needed]Most of the less fertile and sparsely populated land of Western Jutland was never feudalised.[citation needed]East Jutland was more similar to Eastern Denmark in this respect.[citation needed]The north–south ridge forming the border between the fertile eastern hills and sandy western plains has been a significant cultural border until this day, also reflected in differences between the West and East Jutlandic dialect.[citation needed]

When the industrialisation began in the 19th century, the social order was upheaved and with it the focus of the intelligentsia and the educated changed as well.Søren Kierkegaard(1818–1855) grew up in Copenhagen as the son of a stern and religious West Jutlandic wool merchant who had worked his way up from a frugal childhood. The very urban Kierkegaard visited his sombre ancestral lands in 1840, then a very traditional society. Writers likeSteen Steensen Blicher(1782-1848) andH.C. Andersen(1805–1875) were among the first writers to find genuine inspiration in local Jutlandic culture and present it with affection and non-prejudice.[12]

Blicher was of Jutish origin and, soon after his pioneering work, many other writers followed with stories and tales set in Jutland and written in the homestead dialect. Many of these writers are often referred to as theJutland Movement,artistically connected through their engagement with publicsocial realismof the Jutland region.The Golden Age paintersalso found inspiration and motives in the natural beauty of Jutland, includingP. C. Skovgaard,Dankvart Dreyer,and art collective of theSkagen Painters.WriterEvald Tang Kristensen(1843-1929) collected and published extensive accounts on the local rural Jutlandicfolklorethrough many interviews and travels across the peninsula, including songs, legends, sayings and everyday life.[citation needed]

Peter Skautrup Centret atAarhus Universityis dedicated to collect and archive information on Jutland culture and dialects from before the industrialisation. The centre was established in 1932 by Professor in Nordic languagesPeter Skautrup(1896-1982).[13]

With the railway system, and later the automobile andmass communication,the culture of Jutland has merged with and formed the overall Danish national culture, although some unique local traits are still present in some cases. West Jutland is often claimed to have a mentality of self-sustainment, a superiorwork ethicand entrepreneurial spirit as well as slightly more religious and socially conservative values, and there are other voting patterns than in the rest of Denmark.[citation needed]

Dialect[edit]

The distinctiveJutish (or Jutlandic)dialectsdiffer substantially from the standardDanish language,especially those in the West Jutland and South Jutland parts. The Peter Skautrup Centre maintains and publishes an official dictionary of the Jutlandic dialects.[14]Dialect usage, although in decline, is better preserved in Jutland than in eastern Denmark, and Jutlander speech remains a stereotype among manyCopenhagenersand eastern Danes.

Musicians and entertainersIb Grønbech[15][16][17][18]andNiels Hausgaard,both fromVendsysselin Northern Jutland, use a distinct Jutish dialect.[19]

In the southernmost and northernmost parts of Jutland, there are associations striving to conserve their respective dialects, including theNorth Frisian language-speaking areas inSchleswig-Holstein.[20]

Literature[edit]

In the Danish part of Jutland, literature tied to Jutland, and Jutland culture, grew significantly in the 19th and early 20th century. That was a time when large numbers of people migrated to the towns during the industrialisation, and there was a surge of nationalism as well as a quest for social reform during the public foundation of the modern democratic national state.[12]

Steen Steensen Blicherwrote about the Jutland rural culture of his times in the early 1800s. Through his writings, he promoted and preserved the various Jutland dialects, as inE Bindstouw,published in 1842.

Danish social realist and radical writerJeppe Aakjærused Jutlanders and Jutland culture in most of his works, for example inAf gammel Jehannes hans Bivelskistaarri. En bette Bog om stur Folk(1911), which was widely read in its time. He also translated poems ofRobert Burnsto his particular Central Western Jutish dialect.

Karsten Thomsen (1837–1889), an inn-keeper inFrøslevwith artistic aspirations, wrote warmly about his homestead of South Jutland, using the dialect of his region explicitly.

Two songs are often regarded as regional anthems of Jutland:Jylland mellem tvende have( "Jutland between two seas", 1859) byHans Christian AndersenandJyden han æ stærk aa sej( "The Jute, he is strong and tough", 1846) by Steen Steensen Blicher, the latter in dialect.

Jutland native Maren Madsen (1872-1965) emigrated to the American town ofYarmouth, Maine,in the late 19th century. She wrote a memoir documenting the transition,From Jutland's Brown Heather to the Land Across the Sea.[21]

PublisherFrederick William Anthoensenwas born inTorland,South Jutland. He moved to the United States with his parents in 1884.[22]

References[edit]

- ^"Region Nordjylland".Retrieved22 March2015.

- ^Svensson, Harald (1976). "Pingo problems in the Scandinavian countries".Biuletyn Peryglacjalny.26:33–40.

- ^abYorke, Barbara (1990).Kings and kingdoms of early Anglo-Saxon England.London: Seaby. p. 26.ISBN1-85264-027-8.OCLC26404222.

- ^Nugent, Thomas (1766).The History of Vandalia, Vol. 1.London. pp. 165–66.Retrieved6 January2017.

- ^Karen Lerbech (9 November 2019)."Da danskerne udvandrede"[When the Danes emigrated] (in Danish).Danmarks Radio(DR).Retrieved14 February2019.

- ^Henning Bender (20 November 2019)."Udvandringen fra Thisted amt 1868-1910"[The emigration from Thisted county 1868-1910] (in Danish). Historisk Årbog for Thy og Vester Hanherred 2009.Retrieved14 February2019.

- ^Kristian Hvidt (1972)."Mass Emigration from Denmark to the United States 1868-1914".American Studies in Scandinavia (Vol.5, No.2).Copenhagen Business School.Retrieved14 February2019.

- ^Erik Strange Petersen."Det unge demokrati, 1848-1901 - Befolkningsudviklingen"[The young democracy, 1848-1901 - The population trends] (in Danish). Aarhus University.Retrieved17 January2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^Bo Poulsen (22 August 2019)."Stormfloden i 1825, Thyborøn Kanal og kystsikring"[The flood in 1825, Thyborøn Channel and coastal protection].danmarkshistorien.dk(in Danish). Aarhus University.Retrieved13 June2020.

- ^"The Battle of Jutland".History Learning Site.Retrieved2016-07-27.

- ^Historien bag 10. batteri (in Danish)(History behind 10th battery), Vendsyssel Historic Museum

- ^abcInge Lise Pedersen."Jysk som litteratursprog"[Jutlandic as literary language](PDF)(in Danish). Peter Skautrup Centret.

- ^"Peter Skautrup Centret"(in Danish).Retrieved11 January2019.

- ^"Jysk Ordbog"(in Danish). Peter Skautrup Centret.Retrieved11 January2019.

- ^Evanthore Vestergard (2007).Beatleshår og behagesyge: bogen om Ib Grønbech(in Danish). Lindtofte.ISBN978-87-92096-08-1.

- ^"Musik og kærlighed på nordjysk"(in Danish). Appetize. 14 May 2018.Retrieved14 January2019.

- ^Ib Grønbechs whole catalog of songs are performed in his homestead dialect ofVendelbomål.(Maria Præst (1 April 2007)."Grønbechs genstart"(in Danish). Nordjyske. Archived fromthe originalon 15 January 2019.Retrieved15 January2019.)

- ^Palle W. Nielsen (18 July 2007)."Hvad med en onsdag aften med Ib Grønbech i Den Musiske Park?"[What about a Wednesday evening with Ib Grønbech in Den Musiske Park?] (in Danish). Nordjyske. Archived fromthe originalon 14 January 2019.Retrieved14 January2019.

- ^Dialect researcher brands Hausgaard as ambassador of dialects. (Josefine Brader (9 April 2014)."Hausgaard: Folk havde svært ved at forstå mig"[Hausgaard: People had a hard time understanding me] (in Danish). TV2 Nord.Retrieved15 January2019.)

- ^Levitz, David (17 February 2011)."Thirteen languages in Germany are struggling to survive, UNESCO warns".Deutsche Welle.Retrieved4 February2020.

- ^Bouchard, Kelley (March 2012)."Yarmouth history center to break ground in April".Portland Press Herald.

- ^Guide to the Fred Anthoensen Collection, 1901-1969–Bowdoin College

Sources[edit]

- .Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). 1911.