Kansai dialect

This article includes a list of generalreferences,butit lacks sufficient correspondinginline citations.(March 2008) |

| Kansai Japanese | |

|---|---|

| Quan tây biện | |

| Native to | Japan |

| Region | Kansai |

Japonic

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | kink1238 |

Kansai-dialect area | |

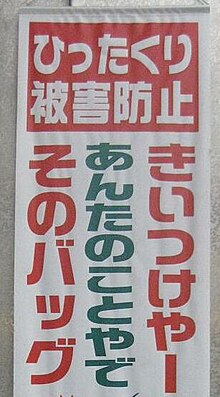

TheKansai dialect(Quan tây biện,Kansai-ben,also known asKansai-hōgen(Quan tây phương ngôn))is a group ofJapanese dialectsin theKansai region(Kinki region) of Japan. In Japanese,Kansai-benis the common name and it is calledKinki dialect(Cận kỳ phương ngôn,Kinki-hōgen)in technical terms. The dialects ofKyotoandOsakaare known asKamigata dialect(Thượng phương ngôn diệp,Kamigatakotoba,orKamigata-go(Thượng phương ngữ)),and were particularly referred to as such in theEdo period.The Kansai dialect is typified by the speech of Osaka, the major city of Kansai, which is referred to specifically asOsaka-ben.It is characterized as being both more melodic and harsher by speakers of the standard language.[1]

Background

[edit]Since Osaka is the largest city in the region and its speakers received the most media exposure over the last century, non-Kansai-dialect speakers tend to associate the dialect of Osaka with the entire Kansai region. However, technically, Kansai dialect is not a single dialect but a group of related dialects in the region. Each major city and prefecture has a particular dialect, and residents take some pride in their particular dialectal variations.

The common Kansai dialect is spoken inKeihanshin(the metropolitan areas of the cities of Kyoto, Osaka andKobe) and its surroundings, a radius of about 50 km (31 mi) around the Osaka-Kyoto area (seeregional differences).[2]This article mainly discusses variations in Keihanshin during the 20th and 21st centuries.

Even in the Kansai region, away from Keihanshin and its surrounding areas, there are dialects that differ from the characteristics generally considered to be Kansai dialect-like.TajimaandTango(exceptMaizuru) dialects in northwest Kansai are too different to be regarded as Kansai dialects and are thus usually included in theChūgoku dialect.Dialects spoken in SoutheasternKii PeninsulaincludingTotsukawaandOwaseare also far different from other Kansai dialects, and considered alanguage island.

TheShikoku dialectand theHokuriku dialectshare many similarities with the Kansai dialects, but are classified separately.

History

[edit]The Kansai dialect has over a thousand years of history. WhenKinaicities such asNaraand Kyoto were Imperial capitals, the Kinai dialect, the ancestor of the Kansai dialect, was thede factostandard Japanese. It had an influence on all of the nation including theEdodialect, the predecessor of modernTokyo dialect.The literature style developed by the intelligentsia inHeian-kyōbecame the model ofClassical Japanese language.

When the political and military center of Japan was moved toEdounder theTokugawa Shogunateand theKantō regiongrew in prominence, the Edo dialect took the place of the Kansai dialect. With theMeiji Restorationand the transfer of the imperial capital from Kyoto to Tokyo, the Kansai dialect became fixed in position as a provincial dialect. See alsoEarly Modern Japanese.

As the Tokyo dialect was adopted with the advent of a national education/media standard in Japan, some features and intraregional differences of the Kansai dialect have diminished and changed. However, Kansai is the second most populated urban region in Japan after Kantō, with a population of about 20 million, so Kansai dialect is still the most widely spoken, known and influential non-standard Japanese dialect. The Kansai dialect's idioms are sometimes introduced into other dialects and even standard Japanese. Many Kansai people are attached to their own speech and have strong regional rivalry against Tokyo.[3]

Since theTaishō period,themanzaiform of Japanese comedy has been developed in Osaka, and a large number of Osaka-based comedians have appeared in Japanese media with Osaka dialect, such asYoshimoto Kogyo.Because of such associations, Kansai speakers are often viewed as being more "funny" or "talkative" than typical speakers of other dialects. Tokyo people even occasionally imitate Kansai dialect to provoke laughter or inject humor.[4]

Phonology

[edit]In phonetic terms, Kansai dialect is characterized by strong vowels and contrasted with Tokyo dialect, characterized by its strong consonants, but the basis of the phonemes is similar. The specific phonetic differences between Kansai and Tokyo are as follows:[5]

Vowels

[edit]

- /u/is nearer to[u]than to[ɯ].

- In Standard,vowel reductionfrequently occurs, but it is rare in Kansai. For example, the polite copuladesu(です)is pronounced nearly as[des]in standard Japanese, but Kansai speakers tend to pronounce it distinctly as/desu/or even/desuː/.

- In some registers, such as informal Tokyo speech,hiatuses/ai,ae,oi/often fuse into/eː/,as inうめえ/umeː/andすげえ/suɡeː/instead ofChỉ い/umai/"yummy" andThê い/suɡoi/"great", but/ai,ae,oi/are usually pronounced distinctly in Kansai dialect. In Wakayama,/ei/is also pronounced distinctly; it usually fuses into/eː/in standard Japanese and almost all other dialects.

- A recurring tendency to lengthen vowels at the end ofmonomoraicnouns. Common examples are/kiː/forMộc/ki/"tree",/kaː/forVăn/ka/"mosquito" and/meː/forMục/me/"eye".

- Contrarily, long vowels in Standard inflections are sometimes shortened. This is particularly noticeable in the volitional conjugation of verbs. For instance,"Hành こうか?"/ikoːka/meaning "shall we go?" is shortened in Kansai to"Hành こか?"/ikoka/.The common phrase of agreement,"そうだ"/soːda/meaning "that's it", is replaced"そや"/soja/or even"せや"/seja/in Kansai.

- When vowels and semivowel/j/follow/i,e/,they sometimespalatalizewith/N/or/Q/.For example,"Hảo きやねん"/sukijaneN/"I love you" becomes' hảo っきゃねん'/suQkjaneN/,Nhật diệu nhật/nitijoːbi/"Sunday" becomes にっちょうび/niQtjoːbi/and chẩn やか/niɡijaka/"lively, busy" becomes にんぎゃか/niNɡjaka/.

Consonants

[edit]

- The syllable ひ/hi/is nearer to[hi]than to[çi].

- Theyotsuganaare two distinct syllables, as they are in Tokyo, but Kansai speakers tend to pronounce じ/zi/and ず/zu/as[ʑi]and[zu]in place of Standard[dʑi]and[dzɯ].

- Intervocalic/ɡ/is pronounced either[ŋ]or[ɡ]in free variation, but[ŋ]is declining now.

- In a provocative speech,/r/becomes[r],similar to theTokyo Shitamachi dialect.

- The use of/h/in place of/s/.Somedebuccalizationof/s/is apparent in most Kansai speakers, but it seems to have progressed more in morphological suffixes and inflections than in core vocabulary. This process has produced はん/-haN/for さん-san"Mr., Ms.", まへん/-maheN/for ません/-maseN/(formal negative form), and まひょ/-mahjo/for ましょう/-masjoː/(formal volitional form), ひちや/hiti-ja/for chất ốc/siti-ja/"pawnshop", among other examples.

- The change of/m/and/b/in some words such as さぶい/sabui/for hàn い/samui/"cold".

- Especially in the rural areas,/z,d,r/are sometimes harmonized or metathesized. For example, でんでん/deNdeN/for toàn nhiên/zeNzeN/"never, not at all", かだら/kadara/or からら/karara/for thể/karada/"body". A play on words around these sound changes goes as follows: Điến xuyên の thủy ẩm んれ phúc らら hạ りや/joroɡawanomirunoNreharararakurarija/for điến xuyên の thủy ẩm んで phúc だだ hạ りや/jodoɡawanomizunoNdeharadadakudarija/"I drank water ofYodo Riverand have the trots ".[6]

- The/r/+ vowel in the verb conjugations is sometimes changed to/N/as well as colloquial Tokyo speech. For example, hà してるねん?/nanisiteruneN/"What are you doing?" often changes hà してんねん?/nanisiteNneN/in fluent Kansai speech.

Pitch accent

[edit]

Thepitch accentin Kansai dialect is very different from the standard Tokyo accent, so non-Kansai Japanese can recognize Kansai people easily from that alone. The Kansai pitch accent is called the Kyoto-Osaka type accent (Kinh phản thức アクセント,Keihan-shiki akusento) in technical terms. It is used in most of Kansai,Shikokuand parts of westernChūbu region.The Tokyo accent distinguishes words only bydownstep,but the Kansai accent distinguishes words also by initial tones, so Kansai dialect has more pitch patterns than standard Japanese. In the Tokyo accent, the pitch between first and secondmoraeusually changes, but in the Kansai accent, it does not always.

Below is a list of simplified Kansai accent patterns. H represents a high pitch and L represents a low pitch.

- High-initial accent(Cao khởi thức,kōki-shiki)or Flat-straight accent(Bình tiến thức,Heishin-shiki)

- The high pitch appears on the first mora and the others are low: H-L, H-L-L, H-L-L-L, etc.

- The high pitch continues for the set mora and the rest are low: H-H-L, H-H-L-L, H-H-H-L,etc.

- The high pitch continues to the last: H-H, H-H-H, H-H-H-H,etc.

- Low-initial accent(Đê khởi thức,teiki-shiki)or Ascent accent(Thượng thăng thức,Jōshō-shiki)

- The pitch rises drastically the middle set mora and falls again: L-H-L, L-H-L-L, L-L-H-L,etc.

- The pitch rises drastically the last mora: L-L-H, L-L-L-H, L-L-L-L-H,etc.

- If high-initial accent words or particles attach to the end of the word, all moras are low: L-L-L(-H), L-L-L-L(-H), L-L-L-L-L(-H)

- With two-mora words, there are two accent patterns. Both of these tend to be realized in recent years as L-H, L-H(-L).[7]

- The second mora rises and falls quickly. If words or particles attach to the end of the word, the fall is sometimes not realized: L-HL, L-HL(-L) or L-H(-L)

- The second mora does not fall. If high-initial words or particles attach to the end of the word, both moras are low: L-H, L-L(-H)

| Kansai | Tokyo | English | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hashi | Kiều | H-L | L-H(-L) | bridge |

| Trứ | L-H | H-L | chopsticks | |

| Đoan | H-H | L-H(-H) | edge | |

| Nihon | Nhật bổn | H-L-L | L-H-L | Japan |

| nihon | Nhị bổn | L-L-H | H-L-L | 2-hon |

| konnichi wa | Kim nhật は | L-H-L-L-H | L-H-H-H-H | good afternoon |

| arigatō | ありがとう | L-L-L-H-L | L-H-L-L-L | thanks |

Grammar

[edit]Many words and grammar structures in Kansai dialect are contractions of theirclassical Japaneseequivalents (it is unusual to contract words in such a way in standard Japanese). For example,chigau(to be different or wrong) becomeschau,yoku(well) becomesyō,andomoshiroi(interesting or funny) becomesomoroi.These contractions follow similar inflection rules as their standard forms sochauis politely saidchaimasuin the same way aschigauis inflected tochigaimasu.

Verbs

[edit]Kansai dialect also hastwo types of regular verb,Ngũ đoạngodan verbs(-uverbs) and nhất đoạnichidan verbs(-ruverbs), and two irregular verbs, lai る/kuru/( "to come" ) and する/suru/( "to do" ), but some conjugations are different from standard Japanese.

The geminated consonants found in godan verbs of standard Japanese verbal inflections are usually replaced with long vowels (oftenshortenedin 3 morae verbs) in Kansai dialect (See alsoOnbin,u-onbin). Thus, for the verb ngôn う/iu,juː/( "to say" ), the past tense in standard Japanese ngôn った/iQta/( "said" ) becomes ngôn うた/juːta/in Kansai dialect. This particular verb is a dead giveaway of a native Kansai speaker, as most will unconsciously say ngôn うて/juːte/instead of ngôn って/iQte/or/juQte/even if well-practiced at speaking in standard Japanese. Other examples of geminate replacement are tiếu った/waraQta/( "laughed" ) becoming tiếu うた/waroːta/or わろた/warota/and thế った/moraQta/( "received" ) becoming thế うた/moroːta/,もろた/morota/or even もうた/moːta/.

Anauxiliary verb] -てしまう/-tesimau/(to finish something or to do something in unintentional or unfortunate circumstances) is contracted to -ちまう/-timau/or -ちゃう/-tjau/in colloquial Tokyo speech but to -てまう/-temau/in Kansai speech. Thus, しちまう/sitimau/,or しちゃう/sitjau/,becomes してまう/sitemau/.Furthermore, as the verb しまう/simau/is affected by the same sound changes as in other ngũ đoạn godan verbs, the past tense of this form is rendered as -てもうた/-temoːta/or -てもた/-temota/rather than -ちまった/-timaQta/or -ちゃった/-tjaQta/:Vong れちまった/wasuretimaQta/or vong れちゃった/wasuretjaQta/( "I forgot [it]" ) in Tokyo is vong れてもうた/wasuretemoːta/or vong れてもた/wasuretemota/in Kansai.

The long vowel of the volitional form is often shortened; for example, sử おう/tukaoː/(the volitional form oftsukau) becomes sử お/tukao/,Thực べよう/tabejoː/(the volitional form of thực べる/taberu/) becomes thực べよ/tabejo/.The irregular verb する/suru/has special volitional form しょ ( う )/sjo(ː)/instead of しよう/sijoː/.The volitional form of another irregular verb lai る/kuru/is lai よう/kojoː/as well as the standard Japanese, but when lai る/kuru/is used as an auxiliary verb -てくる/-tekuru/,-てこよう/-tekojoː/is sometimes replaced with -てこ ( う )/-teko(ː)/in Kansai.

Thecausativeverb ending/-aseru/is usually replaced with/-asu/in Kansai dialect; for example, させる/saseru/(causative form of/suru/) changes さす/sasu/,Ngôn わせる/iwaseru/(causative form of ngôn う/juː/) changes ngôn わす/iwasu/.Its -te form/-asete/and perfective form/-aseta/change to/-asite/and/-asita/;they also appear in transitive ichidan verbs such as kiến せる/miseru/( "to show" ), e.g. Kiến して/misite/for kiến せて/misete/.

The potential verb endings/-eru/for ngũ đoạn godan and -られる/-rareru/for nhất đoạn ichidan, recently often shortened -れる/-reru/(ra-nuki kotoba), are common between the standard Japanese and Kansai dialect. For making their negative forms, it is only to replace -ない/-nai/with -ん/-N/or -へん/-heN/(SeeNegative). However, mainly in Osaka, potential negative form of ngũ đoạn godan verbs/-enai/is often replaced with/-areheN/such as hành かれへん/ikareheN/instead of hành けない/ikenai/and hành けへん/ikeheN/"can't go". This is because/-eheN/overlaps with Osakan negative conjugation. In western Japanese including Kansai dialect, a combination of an adverb よう/joː/and -ん/-N/negative form is used as a negative form of the personal impossibility such as よう ngôn わん/joːiwaN/"I can't say anything (in disgust or diffidence)".

Existence verbs

[edit]In Standard Japanese, the verbiruis used for reference to the existence of ananimateobject, andiruis replaced withoruinhumble languageand some written language. In western Japanese,oruis used not only in humble language but also in all other situations instead ofiru.

Kansai dialect belongs to western Japanese, but いる/iru/and its variation, いてる/iteru/(mainly Osaka), are used in Osaka, Kyoto, Shiga and so on. People in these areas, especially Kyoto women, tend to consider おる/oru/an outspoken or contempt word. They usually use it for mates, inferiors and animals; avoid using for elders (exception: respectful expressionorareruand humble expressionorimasu). In other areas such as Hyogo and Mie, いる/iru/is hardly used and おる/oru/does not have the negative usage. In parts of Wakayama, いる/iru/is replaced with ある/aru/,which is used for inanimate objects in most other dialects.

The verb おる/oru/is also used as asuffixand usually pronounced/-joru/in that case. In Osaka, Kyoto, Shiga, northern Nara and parts of Mie, mainly in masculine speech, -よる/-joru/shows annoying or contempt feelings for a third party, usually milder than -やがる/-jaɡaru/.In Hyogo, southern Nara and parts of Wakayama, -よる/-joru/is used for progressive aspect (SeeAspect).

Negative

[edit]In informal speech, the negative verb ending, which is -ない/-nai/in standard Japanese, is expressed with -ん/-N/or -へん/-heN/,as in hành かん/ikaN/and hành かへん/ikaheN/"not going", which is hành かない/ikanai/in standard Japanese. -ん/-N/is a transformation of the classical Japanese negative form -ぬ/-nu/and is also used for some idioms in standard Japanese. -へん/-heN/is the result of contraction and phonological change of はせん/-waseN/,the emphatic form of/-N/.-やへん/-jaheN/,a transitional form between はせん/-waseN/and へん/-heN/,is sometimes still used for nhất đoạn ichidan verbs. The godan verbs conjugation before-henhas two varieties: the more common conjugation is/-aheN/like hành かへん/ikaheN/,but-ehenlike hành けへん/ikeheN/is also used in Osaka. When the vowel before -へん/-heN/is/-i/,-へん/-heN/often changes to -ひん/-hiN/,especially in Kyoto. The past negative form is -んかった/-NkaQta/and/-heNkaQta/,a mixture of -ん/-N/or -へん/-heN/and the standard past negative form -なかった/-nakaQta/.In traditional Kansai dialect, -なんだ/-naNda/and -へなんだ/-henaNda/is used in the past negative form.

- Ngũ đoạn godan verbs: Sử う/tukau/( "to use" ) becomes sử わん/tukawaN/and sử わへん/tukawaheN/,Sử えへん/tukaeheN/

- Thượng nhất đoạn kami-ichidan verbs: Khởi きる/okiru/( "to wake up" ) becomes khởi きん/okiN/and khởi きやへん/okijaheN/,Khởi きへん/okiheN/,Khởi きひん/okihiN/

- one mora verbs: Kiến る/miru/( "to see" ) becomes kiến ん/miN/and kiến やへん/mijaheN/,Kiến えへん/meːheN/,Kiến いひん/miːhiN/

- Hạ nhất đoạn shimo-ichidan verbs: Thực べる/taberu/( "to eat" ) becomes thực べん/tabeN/and thực べやへん/tabejaheN/,Thực べへん/tabeheN/

- one mora verbs: Tẩm る/neru/( "to sleep" ) becomes tẩm ん/neN/and tẩm やへん/nejaheN/,Tẩm えへん/neːheN/

- s-irregular verb: する/suru/becomes せん/seN/and しやへん/sijaheN/,せえへん/seːheN/,しいひん/siːhiN/

- k-irregular verb: Lai る/kuru/becomes lai ん/koN/and きやへん/kijaheN/,けえへん/keːheN/,きいひん/kiːhiN/

- Lai おへん/koːheN/,a mixture けえへん/keːheN/with standard lai ない/konai/,is also used lately by young people, especially in Kobe.

Generally speaking, -へん/-heN/is used in almost negative sentences and -ん/-N/is used in strong negative sentences and idiomatic expressions. For example, -んといて/-Ntoite/or -んとって/-NtoQte/instead of standard -ないで/-naide/means "please do not to do"; -んでもええ/-Ndemoeː/instead of standard -なくてもいい/-nakutemoiː/means "need not do";-んと ( あかん )/-Nto(akaN)/instead of standard -なくちゃ ( いけない )/-nakutja(ikenai)/or -なければならない/-nakereba(naranai)/means "must do". The last expression can be replaced by -な ( あかん )/-na(akaN)/or -んならん/-NnaraN/.

Imperative

[edit]Kansai dialect has two imperative forms. One is the normal imperative form, inherited fromLate Middle Japanese.The -ろ/-ro/form for ichidan verbs in standard Japanese is much rarer and replaced by/-i/or/-e/in Kansai. The normal imperative form is often followed by よ/jo/or や/ja/.The other is a soft and somewhat feminine form which uses the adverbial(Liên dụng hình,ren'yōkei)(ます/-masu/stem), an abbreviation of adverbial(Liên dụng hình,ren'yōkei)+/nasai/.The end of the soft imperative form is often elongated and is generally followed by や/ja/or な/na/.In Kyoto, women often add よし/-josi/to the soft imperative form.

- godan verbs: Sử う/tukau/becomes sử え/tukae/in the normal form, sử い ( い )/tukai(ː)/in the soft one.

- Thượng nhất đoạn kami-ichidan verbs: Khởi きる/okiru/becomes khởi きい/okiː/(L-H-L) in the normal form, khởi き ( い )/oki(ː)/(L-L-H) in the soft one.

- Hạ nhất đoạn shimo-ichidan verbs: Thực べる/taberu/becomes thực べえ/tabeː/(L-H-L) in the normal form, thực べ ( え )/tabe(ː)/(L-L-H) in the soft one.

- s-irregular verb: する/suru/becomes せえ/seː/in the normal form, し ( い )/si(ː)/in the soft one.

- k-irregular verb: Lai る/kuru/becomes こい/koi/in the normal form, き ( い )/ki(ː)/in the soft one.

In the negative imperative mood, Kansai dialect also has the somewhat soft form which uses theren'yōkei+ な/na/,an abbreviation of theren'yōkei+ なさるな/nasaruna/.な/na/sometimes changes to なや/naja/or ないな/naina/.This soft negative imperative form is the same as the soft imperative and な/na/,Kansai speakers can recognize the difference by accent, but Tokyo speakers are sometimes confused by a commandnot to dosomething, which they interpret as an order todoit. Accent on the soft imperative form is flat, and the accent on the soft negative imperative form has a downstep beforena.

- Ngũ đoạn godan verbs: Sử う/tukau/becomes sử うな/tukauna/in the normal form, sử いな/tukaina/in the soft one.

- Thượng nhất đoạn kami-ichidan verbs: Khởi きる/okiru/becomes khởi きるな/okiruna/in the normal form, khởi きな/okina/in the soft one.

- Hạ nhất đoạn shimo-ichidan verbs: Thực べる/taberu/becomes thực べるな/taberuna/in the normal form, thực べな/tabena/in the soft one.

- s-irregular verb: する/suru/becomes するな/suruna/or すな/suna/in the normal form, しな/sina/in the soft one.

- k-irregular verb: Lai る/kuru/becomes lai るな/kuruna/in the normal form, きな/kina/in the soft one.

Adjectives

[edit]Thestemof adjective forms in Kansai dialect is generally the same as in standard Japanese, except for regional vocabulary differences. The same process that reduced the Classical Japanese terminal and attributive endings (し/-si/and き/-ki/,respectively) to/-i/has reduced also the ren'yōkei ending く/-ku/to/-u/,yielding such forms as tảo う/hajoː/(contraction of tảo う/hajau/) for tảo く/hajaku/( "quickly" ). Dropping the consonant from the final mora in all forms of adjective endings has been a frequent occurrence in Japanese over the centuries (and is the origin of such forms as ありがとう/ariɡatoː/and おめでとう/omedetoː/), but the Kantō speech preserved く/-ku/while reducing し/-si/and き/-ki/to/-i/,thus accounting for the discrepancy in the standard language (see alsoOnbin)

The/-i/ending can be dropped and the last vowel of the adjective's stem can be stretched out for a secondmora,sometimes with a tonal change for emphasis. By this process,omoroi"interesting, funny" becomesomorōandatsui"hot" becomesatsūorattsū.This use of the adjective's stem, often as an exclamation, is seen in classical literature and many dialects of modern Japanese, but is more often used in modern Kansai dialect.

There is not a special conjugated form for presumptive of adjectives in Kansai dialect, it is just addition of やろ/jaro/to the plain form. For example, an かろう/jasukaroː/(the presumptive form of an い/jasui/"cheap" ) is hardly used and is usually replaced with the plain form + やろ/jaro/likes an いやろ/jasuijaro/.Polite suffixes です/だす/どす/desu,dasu,dosu/and ます/-masu/are also added やろ/jaro/for presumptive form instead of でしょう/desjoː/in standard Japanese. For example, kim nhật は tình れでしょう/kjoːwaharedesjoː/( "It may be fine weather today" ) is replaced with kim nhật は tình れですやろ/kjoːwaharedesujaro/.

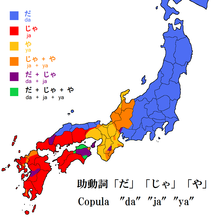

Copulae

[edit]

The standard Japanesecopuladais replaced by the Kansai dialect copulaya.The inflected forms maintain this difference, resulting inyarofordarō(presumptive),yattafordatta(past);darōis often considered to be a masculine expression, butyarois used by both men and women. The negative copulade wa naiorja naiis replaced byya naiorya arahen/arehenin Kansai dialect.Yaoriginated fromja(a variation ofdearu) in late Edo period and is still commonly used in other parts of western Japan likeHiroshima,and is also used stereotypically by old men in fiction.

Yaandjaare used only informally, analogically to the standardda,while the standarddesuis by and large used for the polite (teineigo) copula. For polite speech, -masu,desuandgozaimasuare used in Kansai as well as in Tokyo, but traditional Kansai dialect has its own polite forms.Desuis replaced bydasuin Osaka anddosuin Kyoto. There is another unique polite formomasuand it is often replaced byosuin Kyoto. The usage ofomasu/osuis same asgozaimasu,the polite form of the verbaruand also be used for polite form of adjectives, but it is more informal thangozaimasu.In Osaka,dasuandomasuare sometimes shortened todaandoma.Omasuandosuhave their negative formsomahenandohen.

| impolite | informal | polite1 | polite2 | polite formal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osaka | ja | ya | dasu | de omasu | de gozaimasu |

| Kyoto | dosu | ||||

When some sentence-final particles and a presumptive inflectionyarofollow -suending polite forms,suis often combined especially in Osaka. Today, this feature is usually considered to be dated or exaggerated Kansai dialect.

- -n'na (-su + na), emphasis. e.g.Bochi-bochi den'na.( "So-so, you know." )

- -n'nen (-su + nen), emphasis. e.g.Chaiman'nen.( "It is wrong" )

- -ngana (-su + gana), emphasis. e.g.Yoroshū tanomimangana.( "Nice to meet you" )

- -kka (-su + ka), question. e.g.Mōkarimakka?( "How's business?" )

- -n'no (-su + no), question. e.g.Nani yūteman'no?( "What are you talking about?" )

- -sse (-su + e, a variety of yo), explain, advise. e.g.Ee toko oshiemasse!( "I'll show you a nice place!" )

- -ssharo (-su + yaro), surmise, make sure. e.g.Kyō wa hare dessharo.( "It may be fine weather today" )

Aspect

[edit]In common Kansai dialect, there are two forms for thecontinuous and progressive aspects-teruand -toru;the former is a shortened form of -te irujust as does standard Japanese, the latter is a shortened form of -te oruwhich is common to other western Japanese. The proper use between -teruand -toruis same asiruandoru.

In the expression to the condition of inanimate objects, -taruor -taaruform, a shortened form of -te aru.In standard Japanese, -te aruis only used withtransitive verbs,but Kansai -taruor -taaruis also used withintransitive verbs.One should note that -te yaru,"to do for someone," is also contracted to -taru(-charuin Senshu and Wakayama), so as not to confuse the two.

Other Western Japanese as Chūgoku and Shikoku dialects has the discrimination ofgrammatical aspect,-yoruinprogressiveand -toruinperfect.In Kansai, some dialects of southern Hyogo and Kii Peninsula have these discrimination, too. In parts of Wakayama, -yoruand -toruare replaced with -yaruand -taaru/chaaru.

Politeness

[edit]

Historically, extensive use of keigo (honorific speech) was a feature of the Kansai dialect, especially in Kyōto, while the Kantō dialect, from which standard Japanese developed, formerly lacked it. Keigo in standard Japanese was originally borrowed from the medieval Kansai dialect. However, keigo is no longer considered a feature of the dialect since Standard Japanese now also has it. Even today, keigo is used more often in Kansai than in the other dialects except for the standard Japanese, to which people switch in formal situations.

In modern Kansai dialect, -haru(sometimes -yaharuexceptgodanverbs, mainly Kyōto) is used for showing reasonable respect without formality especially in Kyōto. The conjugation before -haruhas two varieties between Kyōto and Ōsaka (see the table below). In Southern Hyōgo, including Kōbe,-te yais used instead of -haru.In formal speech, -naharuand -haruconnect with -masuand -te yachanges -te desu.

-Haruwas originally a shortened form of -naharu,a transformation of -nasaru.-Naharuhas been dying out due to the spread of -harubut its imperative form -nahare(mainly Ōsaka) or -nahai(mainly Kyōto, also -nai) and negative imperative form -nasan'naor -nahan'nahas comparatively survived because -harulacks an imperative form. In more honorific speech,o- yasu,a transformation ofo- asobasu,is used especially in Kyōto and its original form is same to its imperative form, showing polite invitation or order.Oide yasuandokoshi yasu(more respectful), meaning "welcome", are the common phrases of sightseeing areas in Kyōto. -Te okun nahare(also -tokun nahare,-toku nahare) and -te okure yasu(also -tokure yasu,-tokuryasu) are used instead of -te kudasaiin standard Japanese.

| use | see | exist | eat | do | come | -te form | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| original | tsukau | miru | iru, oru | taberu | suru | kuru | -teru |

| o- yasu | otsukaiyasu | omiyasu | oiyasu | otabeyasu | oshiyasu | okoshiyasu, oideyasu | -toiyasu |

| -naharu | tsukainaharu | minaharu | inaharu | tabenaharu | shinaharu | kinaharu | -tenaharu |

| -haru in Kyōto | tsukawaharu | miharu | iharu iteharu (mainly Ōsaka) |

tabeharu | shiharu | kiharu | -taharu |

| -haru in Ōsaka | tsukaiharu | -teharu | |||||

| -yaharu | miyaharu | iyaharu yaharu |

tabeyaharu | shiyaharu shaharu |

kiyaharu kyaharu |

-teyaharu | |

| -te ya | tsukōte ya | mite ya | otte ya | tabete ya | shite ya | kite ya | -totte ya |

Particles

[edit]There is some difference in the particles between Kansai dialect and standard Japanese. In colloquial Kansai dialect, case markers(Cách trợ từ,kaku-joshi)are often left out especially theaccusative caseoand the quotation particlestoandte(equivalent tottein standard). The ellipsis oftoandtehappens only before two verbs:yū(to say) andomou(to think). For example,Tanaka-san to yū hito( "a man called Mr. Tanaka" ) can change toTanaka-san yū hito.Andto yūis sometimes contracted tochūortchūinstead ofte,tsūorttsūin Tokyo. For example,nanto yū koto da!ornante kotta!( "My goodness!" ) becomesnanchū kotcha!in Kansai.

The interjectory particle(Gian đầu trợ từ,kantō-joshi)naornaais used very often in Kansai dialect instead ofneorneein standard Japanese. In standard Japanese,naais considered rough masculine style in some context, but in Kansai dialectnaais used by both men and women in many familiar situations. It is not only used as interjectory particle (as emphasis for the imperative form, expression an admiration, and address to listeners, for example), and the meaning varies depending on context and voice intonation, so much so thatnaais called the world's third most difficult word to translate.[8]Besidesnaaandnee,noois also used in some areas, butnoois usually considered too harsh a masculine particle in modern Keihanshin.

Karaandnode,the conjunctive particles(Tiếp 続 trợ từ,setsuzoku-joshi)meaning "because," are replaced bysakaioryotte;niis sometimes added to the end of both, andsakaichanges tosakein some areas.Sakaiwas so famous as the characteristic particle of Kansai dialect that a special saying was made out of it: "Sakaiin Osaka andBerabōin Edo "(Đại phản さかいに giang hộ べらぼう,Ōsaka sakai ni Edo berabō)".However, in recent years, the standardkaraandnodehave become dominant.

Kateorkatteis also characteristic particle of Kansai dialect, transformation ofka tote.Katehas two usages. Whenkateis used with conjugative words, mainly in the past form and the negative form, it is the equivalent of the English "even if" or "even though", such asKaze hiita kate, watashi wa ryokō e iku( "Even if [I] catch a cold, I will go on the trip" ). Whenkateis used with nouns, it means something like "even", "too," or "either", such asOre kate shiran( "I don't know, either" ), and is similar to the particlemoanddatte.

Sentence final particles

[edit]Thesentence-final particles(Chung trợ từ,shū-joshi)used in Kansai differ widely from those used in Tokyo. The most prominent to Tokyo speakers is the heavy use ofwaby men. In standard Japanese, it is used exclusively by women and so is said to sound softer. In western Japanese including Kansai dialect, however, it is used equally by both men and women in many different levels of conversation. It is noted that the feminine usage ofwain Tokyo is pronounced with a rising intonation and the Kansai usage ofwais pronounced with a falling intonation.

Another difference in sentence final particles that strikes the ear of the Tokyo speaker is thenenparticle such asnande ya nen!,"you gotta be kidding!" or "why/what the hell?!", a stereotypetsukkomiphrase in the manzai. It comes fromno ya(particleno+ copulaya,alson ya) and much the same as the standard Japaneseno da(alson da).Nenhas some variation, such asneya(intermediate form betweenno yaandnen),ne(shortened form), andnya(softer form ofneya). When a copula precedes these particles,da+no dachanges tona no da(na n da) andya+no yachanges tona no ya(na n ya), butya+nendoes not change tona nen.No dais never used with polite form, butno yaandnencan be used with formal form such asnande desu nen,a formal form ofnande ya nen.In past tense,nenchanges to-ten;for example, "I love you" would besuki ya nenorsukkya nen,and "I loved you" would besuki yatten.

In the interrogative sentence, the use ofnenandno yais restricted to emphatic questions and involvesinterrogative words.For simple questions,(no) kais usually used andkais often omitted as well as standard Japanese, butnois often changednornon(somewhat feminine) in Kansai dialect. In standard Japanese,kaiis generally used as a masculine variation ofka,but in Kansai dialect,kaiis used as an emotional question and is mainly used for rhetorical question rather than simple question and is often used in the forms askaina(softer) andkaiya(harsher). Whenkaifollows the negative verb ending -n,it means strong imperative sentence. In some areas such as Kawachi and Banshu,keis used instead ofka,but it is considered a harsh masculine particle in common Kansai dialect.

The emphatic particleze,heard often from Tokyo men, is rarely heard in Kansai. Instead, the particledeis used, arising from the replacement ofzwithdin words. However, despite the similarity withze,the Kansaidedoes not carry nearly as heavy or rude a connotation, as it is influenced by the lesser stress on formality and distance in Kansai. In Kyoto, especially feminine speech,deis sometimes replaced withe.The particlezois also replaced todoby some Kansai speakers, butdocarries a rude masculine impression unlikede.

The emphasis ortag questionparticlejan kain the casual speech of Kanto changes toyan kain Kansai.Yan kahas some variations, such as a masculine variationyan ke(in some areas, butyan keis also used by women) and a shortened variationyan,just likejanin Kanto.Jan kaandjanare used only in informal speech, butyan kaandyancan be used with formal forms likesugoi desu yan!( "It is great!" ). Youngsters often useyan naa,the combination ofyanandnaafor tag question.

Vocabulary

[edit]

In some cases, Kansai dialect uses entirely different words. The verbhokasucorresponds to standard Japanesesuteru"to throw away", andmetchacorresponds to the standard Japanese slangchō"very".Chō,in Kansai dialect, means "a little" and is a contracted form ofchotto.Thus the phrasechō matte"wait a minute" by a Kansai person sounds strange to a Tokyo person.

Some Japanese words gain entirely different meanings or are used in different ways when used in Kansai dialect. One such usage is of the wordnaosu(usually used to mean "correct" or "repair" in the standard language) in the sense of "put away" or "put back." For example,kono jitensha naoshitemeans "please put back this bicycle" in Kansai, but many standard speakers are bewildered since in standard Japanese it would mean "please repair this bicycle".

Another widely recognized Kansai-specific usage is ofaho.Basically equivalent to the standardbaka"idiot, fool",ahois both a term of reproach and a term of endearment to the Kansai speaker, somewhat like Englishtwitorsilly.Baka,which is used as "idiot" in most regions, becomes "complete moron" and a stronger insult thanaho.Where a Tokyo citizen would almost certainly object to being calledbaka,being calledahoby a Kansai person is not necessarily much of an insult. Being calledbakaby a Kansai speaker is however a much more severe criticism than it would be by a Tokyo speaker. Most Kansai speakers cannot stand being calledbakabut don't mind being calledaho.

Well-known words

[edit]Here are some words and phrases famous as part of the Kansai dialect:

| Kansai dialect | accent | Standard Japanese | English | Note | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| akanorakahen | H-H-H, H-L-L-L | dame,ikemasen,shimatta | wrong, no good, must, oh no! | abbreviation of "rachi ga akanu";akimasenorakimahen(H-H-H-H-H) for polite speech;-ta(ra) akanmeans "must not...";-na akanand-nto akanmeans "must...". | Tabetara akan.= "You must not eat.":Tabena/Tabento akan= "You must eat." |

| aho,ahō | L-HL, L-H-L | baka | silly, idiot, fool | sometimes used friendly with a joke; this accompanies a stereotype thatbakais considered a much more serious insult in Kansai;Ahondara(L-L-L-H-L) is strong abusive form;Ahokusai(L-L-H-L-L) andAhorashii(L-L-H-L-L) are adjective form; originallyahauand said to derive from a Chinese wordA ngốc;ā dāiinMuromachi period.[9] | Honma aho ya naa.= "You are really silly." |

| beppin | H-H-H | bijin | beautiful woman | Originally written biệt phẩm, meaning a product of exceptional quality; extrapolated to apply to women of exceptional beauty, rewritten as biệt tần. Often appended with-san. | Beppin-san ya na.= "You are a pretty woman." |

| charinko,chari | jitensha | bicycle | said to derive either fromonomatopoeiaof the bell, or corrupted fromjajeongeo,aKoreanword for "bicycle" used byOsaka-born Koreans.Has spread out to most of Japan in recent decades. | Eki made aruite ikun?Uun, chari de iku wa.( "Are you walking to the station?" "No, I'm going by bike." ) | |

| chau | H-H | chigau,de wa nai,janai | that isn't it, that isn't good, nope, wrong | reduplicationchau chauis often used for informal negative phrase | Are, chauchau chau?Chau chau, chauchau chau n chau?= "It is aChow Chow,isn't it? "" No, it isn't a Chow Chow, is it? "(a famous pun with Kansai dialect) |

| dabo | L-HL | baka | silly, idiot, fool | used in Kobe and Banshu; harsher thanaho | |

| donai | H-H-H | donna,dō | how (demonstrative) | konaimeanskonna(such, like this);sonaimeanssonna(such, like it);anaimeansanna(such, like that) | Donai yatta?= "How was it?" |

| do | excessively (prefix) | often used with bad meanings; also used in several dialects and recently standard Japanese | do-aho= "terribly fool"do-kechi= "terribly miser" | ||

| dotsuku | H-H-H | naguru | to clobber somebody | do+tsuku( đột く; prick, push); alsodozuku | Anta, dotsuku de!= "Hey, I'll clobber you!" |

| donkusai | L-L-H-L-L | manuke,nibui | stupid, clumsy, inefficient, lazy | literally "slow-smelling" (ĐộnXú い) | |

| ee | L-H | yoi,ii | good, proper, all right | used only in Plain form; other conjugations are same asyoi(Perfective formyokattagenerally does not changeekatta); also used in other western Japan and Tohoku | Kakko ee de.= "You look cool." |

| egetsunai | H-H-H-L-L | akudoi,iyarashii,rokotsu-na | indecent, vicious, obnoxious | Egetsunai yarikata= "Indecent way" | |

| erai | H-L-L | erai,taihen | great, high-status, terrible, terribly | the usage as meaning "terrible" and "terribly" is more often in Kansai than in Tokyo; also sometimes used as meaning "tired" asshindoiin Chubu and western Japan | Erai kotcha!(<erai koto ja) = "It is a terrible/difficult thing/matter!" |

| gotsui | H-L-L | ikatsui,sugoi | rough, huge | a variation of the adjective formgottsuis used as "very" or "terribly" likemetcha | Gottsu ee kanji= "feelin' real good" |

| gyōsan | H-L-L-L or L-L-H-L | takusan | a lot of, many | alsoyōsan,may be a mixture ofgyōsanandyōke;also used in other western Japan;NgưỡngSơnin kanji | Gyōsan tabe ya.= "Eat heartily." |

| hannari | H-L-L-L or L-L-H-L | hanayaka,jōhin | elegant, splendid, graceful | mainly used in Kyoto | Hannari-shita kimono= "Elegant kimono" |

| hiku | H-H | shiku | to spread on a flat surface (e.g. bedding, butter) | A result of the palatalization of "s" occurring elsewhere in the dialect. | Futon hiitoite ya.= "Lay out the futons, will you?" |

| hokasu | H-H-H | suteru | to throw away, to dump | alsohoru(H-H). Note particularly that the phrase "gomi (o) hottoite"means" throw out the garbage "in Kansai dialect, but" let the garbage be "in standard Japanese. | Sore hokashitoite.= "Dump it." |

| honde | H-H-H | sorede | and so, so that (conjunction) | Honde na, kinō na, watashi na...= "And, in yesterday, I..." | |

| honnara,hona | H-H-L-L, H-L | (sore)dewa,(sore)ja,(sore)nara | then, in that case, if that's true (conjunction) | often used for informal good-by. | Hona mata.= "Well then." |

| honma | L-L-H, H-H-H | hontō | true, real | honma-mon,equivalent to Standardhonmono,means "genuine thing"; also used in other western Japan;BổnChânin kanji | Sore honma?= "Is that true?" |

| ikezu | L-H-L | ijiwaru | spiteful, ill-natured | Ikezu sentoitee na.= "Don't be spiteful to me." | |

| itemau,itekomasu | H-H-H-H, H-H-H-H-H | yattsukeru,yatchimau | to beat, to finish off | Itemau do, ware!= "I'll finish you off!" (typical fighting words) | |

| kamahenorkamehen | H-L-L-L | kamawanai | never mind; it doesn't matter | abbreviation of "kamawahen" | Kamahen, kamahen.= "It doesn't matter: it's OK." |

| kanawan | H-H-L-L | iya da,tamaranai | can't stand it; unpleasant; unwelcome | alsokanan(H-L-L) | Kō atsui to kanawan naa.= "I can't stand this hot weather." |

| kashiwa | L-H-L | toriniku | chicken (food) | compared the colour of plumage of chickens to the colour of leaves of thekashiwa;also used in other western Japan and Nagoya | Kashiwa hito-kire chōdai.= "Give me a cut of chicken." |

| kattaa shatsu,kattā | H-H-H L-L, H-L-L | wai shatsu( "Y-shirt" ) | dress shirt | wasei-eigo.originally a brand ofMizuno,a sportswear company in Osaka.kattaais apunof "cutter" and "katta"(won, beat, overcame). | |

| kettai-na | H-L-L-L | kimyō-na,hen-na,okashi-na,fushigi-na | strange | Kettai-na fuku ya na.= "They are strange clothes." | |

| kettakuso warui | H-H-H-H H-L-L | imaimashii,haradatashii | damned, stupid, irritating | kettai+kuso"shit" +warui"bad" | |

| kii warui | H-H H-L-L | kanji ga warui,iyana kanji | be not in a good feeling | kiiis a lengthened vowel form ofki(Khí). | |

| kosobaiorkoshobai | H-H-L-L | kusuguttai | ticklish | shortened form ofkosobayui;also used in other western Japan | |

| maido | L-H-L | dōmo | commercial greeting | the original meaning is "Thank you always".MỗiĐộin kanji. | Maido, irasshai!= "Hi, may I help you?" |

| makudo | L-H-L | makku | McDonald's | abbreviation ofmakudonarudo(Japanese pronunciation of "McDonald's" ) | Makudo iko.= "Let's go to McDonald's." |

| mebachiko | L-H-L-L | monomorai | stye | meibo(H-L-L) in Kyoto and Shiga. | |

| metchaormessaormutcha | L-H | totemo,chō | very | mostly used by younger people. alsobari(L-H) in southern Hyogo, adopted from Chugoku dialect. | Metcha omoroi mise shitteru de.= "I know a really interesting shop." |

| nanbo | L-L-H | ikura,ikutsu | how much, no matter how, how old, how many | transformation ofnanihodo(HàTrình); also used in other western Japan, Tohoku and Hokkaido. | Sore nanbo de kōta n?= "How much did you pay for it?" |

| nukui | H-L-L | atatakai,attakai | warm | also used in other western Japan | |

| ochokuru | H-H-H-H | karakau,chakasu | to make fun of, to tease | Ore ochokuru no mo eekagen ni see!= "That's enough to tease me!" | |

| okan,oton | L-H-L, L-H-L | okaasan,otōsan | mother, father | very casual form | |

| ōkini | H-L-H-L or L-L-H-L | arigatō | thanks | abbreviation of "ōki ni arigatō"(thank you very much,ōki nimeans "very much" ); of course,arigatōis also used; sometimes, it is used ironically to mean "No thank you"; alsoōkeni | Maido ōkini!= "Thanks always!" |

| otchan | H-H-H | ojisan | uncle, older man | a familiar term of address for a middle-aged man; also used as a first personal pronoun; the antonym "aunt, older woman" isobachan(also used in standard Japanese); alsoossanandobahan,but ruder thanotchanandobachan | Otchan, takoyaki futatsu!Aiyo!= (conversation with a takoyaki stall man) "Two takoyaki please, mister!" "All right!" |

| shaanai | H-H-L-L | shōganai,shikata ga nai | it can't be helped | also used some other dialects | |

| shibaku | H-H-H | naguru,tataku | to beat somebody (with hands or rods) | sometimes used as a vulgar word meaning "to go" or "to eat" such asChaa shibakehen?"Why don't you go to cafe?" | Shibaitaro ka!( <shibaite yarō ka) = "Do you want me to give you a beating?" |

| shindoi | L-L-H-L | tsukareru,tsurai,kurushii | tired, exhausted | change fromshinrō(Tân 労;hardship);shindoihas come to be used throughout Japan in recent years. | Aa shindo.= "Ah, I'm tired." |

| shōmonai | L-L-H-L-L | tsumaranai,omoshirokunai,kudaranai | dull, unimportant, uninteresting | change fromshiyō mo nai( sĩ dạng も vô い, means "There isn't anything" ); also used some other dialects | |

| sunmasenorsunmahen | L-L-L-L-H | sumimasen,gomen nasai | I'm sorry, excuse me, thanks | suman(H-L-L) in casual speech; alsokan'nin(KhamNhẫn,L-L-H-L) for informal apology instead of standardkanben(Khám biện) | Erai sunmahen.= "I'm so sorry." |

| taku | H-H | niru | to boil, to simmer | in standard Japanese,takuis used only for cooking rice; also used in other western Japan | Daikon yō taketa.= "Thedaikonwas boiled well. " |

| waya | H-L | mucha-kucha,dainashi,dame | going for nothing, fruitless | also used in other western Japan, Nagoya and Hokkaido | Sappari waya ya wa.= "It's no good at all." |

| yaru | H-H | yaru,ageru | to give (informal) | used more widely than in standard Japanese towards equals as well as inferiors; when used as helper auxiliaries, -te yaruusually shortened -taru | |

| yome | H-H | tsuma,okusan,kamisan,kanai | wife | originally means "bride" and "daughter-in-law" in standard, but an additional meaning "wife" is spread from Kansai; often used asyome-sanoryome-han | anta toko no yome-han= "your wife" |

| yōke | H-L-L | takusan | a lot of, many | change fromyokei( dư kế, means "extra, too many" ); a synonymous withgyōsan |

Pronouns and honorifics

[edit]Standard first-person pronouns such aswatashi,bokuandoreare also generally used in Kansai, but there are some local pronoun words.Watashihas many variations:watai,wate(both gender),ate(somewhat feminine), andwai(masculine, casual). These variations are now archaic, but are still widely used in fictitious creations to represent stereotypical Kansai speakers especiallywateandwai.Elderly Kansai men frequently usewashias well as other western Japan.Uchiis famous for the typical feminine first-person pronoun of Kansai dialect and it is still popular among Kansai girls.

In Kansai,omaeandantaare often used for the informal second-person pronoun.Anatais hardly used. Traditional local second-person pronouns includeomahan(omae+-han),anta-hanandansan(both areanta+-san,butanta-hanis more polite). An archaic first-person pronoun,ware,is used as a hostile and impolite second-person pronoun in Kansai.Jibun(Tự phân) is a Japanese word meaning "oneself" and sometimes "I", but it has an additional usage in Kansai as a casual second-person pronoun.

In traditional Kansai dialect, the honorific suffix-sanis sometimes pronounced -hanwhen -sanfollowsa,eando;for example,okaasan( "mother" ) becomesokaahan,andSatō-san( "Mr. Satō" ) becomesSatō-han.It is also the characteristic of Kansai usage of honorific suffixes that they can be used for some familiar inanimate objects as well, especially in Kyoto. In standard Japanese, the usage is usually considered childish, but in Kansai,o-imo-san,o-mame-sanandame-chanare often heard not only in children's speech but also in adults' speech. The suffix-sanis also added to some familiar greeting phrases; for example,ohayō-san( "good morning" ) andomedetō-san( "congratulations" ).

Regional differences

[edit]Since Kansai dialect is actually a group of related dialects, not all share the same vocabulary, pronunciation, or grammatical features. Each dialect has its own specific features discussed individually here.

Here is a division theory of Kansai dialects proposed by Mitsuo Okumura in 1968;[2]■ shows dialects influenced by Kyoto dialect and □ shows dialects influenced by Osaka dialect, proposed by Minoru Umegaki in 1962.[5]

- Inner Kansai dialect

- ■Kyoto dialect (southern part ofKyoto Prefecture,especially the city ofKyoto)

- Gosho dialect (old court dialect ofKyoto Gosho)

- Machikata dialect (Kyoto citizens' dialect including several social dialects)

- Tanba dialect (southeastern part of formerTanba Province)

- Southern Yamashiro dialect (southern part of formerYamashiro Province)

- □Osaka dialect (Osaka Prefecture,especially the city ofOsaka)

- Settsu dialect (Northern part of Osaka Prefecture, formerSettsu Province)

- Senba dialect (old merchant dialect in the central area of the city of Osaka)

- Kawachi dialect (eastern part of Osaka Prefecture, formerKawachi Province)

- Senshū dialect (southwestern part of Osaka Prefecture, formerIzumi Province)

- Settsu dialect (Northern part of Osaka Prefecture, formerSettsu Province)

- □Kobe dialect (the city ofKobe,Hyōgo Prefecture)

- □Northern Nara dialect (northern part ofNara Prefecture)

- ■Shiga dialect (main part ofShiga Prefecture)

- ■Iga dialect (northwestern part of Mie Prefecture, formerIga Province)

- ■Kyoto dialect (southern part ofKyoto Prefecture,especially the city ofKyoto)

- Outer Kansai dialect

- Northern Kansai dialect

- ■Tanba dialect (northern part of former Tanba Province andMaizuru)

- ■Southern Fukui dialect (southern part ofFukui Prefecture,formerWakasa ProvinceandTsuruga)

- ■Kohoku dialect (northeastern part of Shiga Prefecture)

- Western Kansai dialect

- □Banshū dialect (southwestern part of Hyōgo Prefecture, formerHarima Province)

- ■Tanba dialect (southwestern part of former Tanba Province)

- Eastern Kansai dialect

- ■Ise dialect (northern part of Mie Prefecture, formerIse Province)

- Southern Kansai dialect

- Kishū dialect (Wakayama Prefectureand southern part of Mie Prefecture, formerKii Province)

- Shima dialect (southeastern part of Mie Prefecture, formerShima Province)

- □Awaji dialect(Awaji Islandin Hyōgo Prefecture)

- Northern Kansai dialect

- Totsukawa-Kumano dialect (southern part ofYoshinoandOwase-Kumanoarea in southeasternKii Peninsula)

Osaka

[edit]Osaka-ben(Đại phản biện) is often identified with Kansai dialect by most Japanese, but some of the terms considered to be characteristic of Kansai dialect are actually restricted to Osaka and its environs. Perhaps the most famous is the termmōkarimakka?,roughly translated as "how is business?", and derived from the verbmōkaru( trữ かる), "to be profitable, to yield a profit". This is supposedly said as a greeting from one Osakan to another, and the appropriate answer is another Osaka phrase,maa, bochi bochi denna"well, so-so, y'know".

The idea behindmōkarimakkais that Osaka was historically the center of the merchant culture. The phrase developed among low-class shopkeepers and can be used today to greet a business proprietor in a friendly and familiar way but is not a universal greeting. The latter phrase is also specific to Osaka, in particular the termbochi bochi(L-L-H-L). This means essentially "so-so": getting better little by little or not getting any worse. Unlikemōkarimakka,bochi bochiis used in many situations to indicate gradual improvement or lack of negative change. Also,bochi bochi(H-L-L-L) can be used in place of the standard Japanesesoro soro,for instancebochi bochi iko ka"it is about time to be going".[10]

In the Edo period,Senba-kotoba( thuyền tràng ngôn diệp ), a social dialect of the wealthy merchants in thecentral business districtof Osaka, was considered the standard Osaka-ben. It was characterized by the polite speech based on Kyoto-ben and the subtle differences depending on the business type, class, post etc. It was handed down inMeiji,TaishōandShōwaperiods with some changes, but after thePacific War,Senba-kotoba became nearly an obsolete dialect due to the modernization of business practices. Senba-kotoba was famous for a polite copulagowasuorgoasuinstead of common Osakan copulaomasuand characteristic forms for shopkeeper family mentioned below.

| An example of forms of address for shopkeeper family in Senba[11] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Southern branches of Osaka-ben, such asSenshū-ben(Tuyền châu biện) andKawachi-ben(Hà nội biện), are famous for their harsh locution, characterized by trilled "r", the question particleke,and the second personware.The farther south in Osaka one goes, the cruder the language is considered to be, with the local Senshū-ben ofKishiwadasaid to represent the peak of harshness.[12]

Kyoto

[edit]

Kyōto-ben( kinh đô biện ) orKyō-kotoba(Kinh ngôn diệp) is characterized by development of politeness and indirectness expressions. Kyoto-ben is often regarded as elegant and feminine dialect because of its characters and the image ofGion'sgeisha(geiko-hanandmaiko-hanin Kyoto-ben), the most conspicuous speakers of traditional Kyoto-ben.[13]Kyoto-ben is divided into the court dialect calledGosho kotoba( ngự sở ngôn diệp ) and the citizens dialect calledMachikata kotoba( đinh phương ngôn diệp ). The former was spoken by court noble before moving the Emperor to Tokyo, and some phrases inherit at a fewmonzeki.The latter has subtle difference at each social class such as old merchant families atNakagyo,craftsmen atNishijinandgeikoatHanamachi(Gion,Miyagawa-chōetc.)

Kyoto-ben was thede factostandard Japanese from 794 until the 18th century and some Kyoto people are still proud of their accent; they get angry when Tokyo people treat Kyoto-ben as a provincial accent.[13]However, traditional Kyoto-ben is gradually declining except in the world ofgeisha,which prizes the inheritance of traditional Kyoto customs. For example, a famous Kyoto copuladosu,instead of standarddesu,is used by a few elders andgeishanow.[14]

The verb inflection-haruis an essential part of casual speech in modern Kyoto. In Osaka and its environs,-haruhas a certain level of politeness above the base (informal) form of the verb, putting it somewhere between the informal and the more polite-masuconjugations. However, in Kyoto, its position is much closer to the informal than it is to the polite mood, owing to its widespread use. Kyoto people, especially elderly women, often use -harufor their family and even for animals and weather.[15]

Tango-ben(Đan hậu biện) spoken in northernmost Kyoto Prefecture, is too different to be regarded as Kansai dialect and usually included in Chūgoku dialect. For example, the copulada,the Tokyo-type accent, the honorific verb ending -naruinstead of -haruand the peculiarly diphthong[æː]such as[akæː]forakai"red".

Hyogo

[edit]Hyōgo Prefectureis the largest prefecture in Kansai, and there are some different dialects in the prefecture. As mentioned above,Tajima-ben(Đãn mã biện) spoken in northern Hyōgo, formerTajima Province,is included inChūgoku dialectas well as Tango-ben. Ancient vowel sequence /au/ changed[oː]in many Japanese dialects, but in Tajima,TottoriandIzumodialects, /au/ changed[aː].Accordingly, Kansai wordahō"idiot" is pronouncedahaain Tajima-ben.

The dialect spoken in southwestern Hyōgo, formerHarima Provincealias Banshū, is calledBanshū-ben.As well as Chūgoku dialect, it has the discrimination of aspect,-yoruin progressive and-toruin perfect. Banshū-ben is notable for transformation of-yoruand-toruinto-yōand-tō,sometimes-yonand-ton.Another feature is the honorific copula-te ya,common inTanba,MaizuruandSan'yōdialects. In addition, Banshū-ben is famous for an emphatic final particledoiordoiyaand a question particlekeorko,but they often sound violent to other Kansai speakers, as well as Kawachi-ben.Kōbe-ben(Thần hộ biện) spoken inKobe,the largest city of Hyogo, is the intermediate dialect between Banshū-ben and Osaka-ben and is well known for conjugating-yōand-tōas well as Banshū-ben.

Awaji-ben(Đạm lộ biện) spoken inAwaji Island,is different from Banshū/Kōbe-ben and mixed with dialects of Osaka, Wakayama andTokushima Prefecturesdue to the intersecting location of sea routes in theSeto Inland Seaand theTokushima Domainrule in Edo period.

Mie

[edit]The dialect inMie Prefecture,sometimes calledMie-ben(Tam trọng biện), is made up ofIse-ben(Y thế biện) spoken in mid-northern Mie,Shima-ben(Chí ma biện) spoken in southeastern Mie andIga-ben(Y hạ biện) spoken in western Mie. Ise-ben is famous for a sentence final particlenias well asde.Shima-ben is close to Ise-ben, but its vocabulary includes many archaic words. Iga-ben has a unique request expression-te daakoinstead of standard-te kudasai.

They use the normal Kansai accent and basic grammar, but some of the vocabulary is common to theNagoya dialect.For example, instead of -te haru(respectful suffix), they have the Nagoya-style -te mieru.Conjunctive particlesdeandmonde"because" is widely used instead ofsakaiandyotte.The similarity to Nagoya-ben becomes more pronounced in the northernmost parts of the prefecture; the dialect ofNagashimaandKisosaki,for instance, could be considered far closer to Nagoya-ben than to Ise-ben.

In and aroundIse city,some variations on typical Kansai vocabulary can be found, mostly used by older residents. For instance, the typical expressionōkiniis sometimes pronouncedōkinain Ise. Near theIsuzu RiverandNaikū shrine,some old men use the first-person pronounotai.

Wakayama

[edit]Kishū-ben(Kỷ châu biện) orWakayama-ben( hòa ca sơn biện ), the dialect in old provinceKii Province,present-dayWakayama Prefectureand southern parts of Mie Prefecture, is fairly different from common Kansai dialect and comprises many regional variants. It is famous for heavy confusion ofzandd,especially on the southern coast. The ichidan verb negative form-noften changes-ranin Wakayama such astaberaninstead oftaben( "not eat" );-henalso changes-yanin Wakayama, Mie and Nara such astabeyaninstead oftabehen.Wakayama-ben has specific perticles.Yōis often used as sentence final particle.Rafollows the volitional conjugation of verbs asiko ra yō!( "Let's go!" ).Noshiis used as soft sentence final particle.Yashiteis used as tag question. Local words areakanainstead ofakan,omoshaiinstead ofomoroi,aga"oneself",teki"you",tsuremote"together" and so on. Wakayama people hardly ever use keigo, which is rather unusual for dialects in Kansai.

Shiga

[edit]Shiga Prefectureis the eastern neighbor of Kyoto, so its dialect, sometimes calledShiga-ben( tư hạ biện ) orŌmi-ben(Cận giang biện) orGōshū-ben( giang châu biện ), is similar in many ways to Kyoto-ben. For example, Shiga people also frequently use-haru,though some people tend to pronounce-aruand-te yaaruinstead of-haruand-te yaharu.Some elderly Shiga people also use-raruas a casual honorific form. The demonstrative pronounso-often changes toho-;for example,so yabecomesho yaandsore(that) becomeshore.InNagahama,people use the friendly-sounding auxiliary verb-ansuand-te yansu.Nagahama andHikonedialects has a unique final particlehonas well asde.

Nara

[edit]The dialect inNara Prefectureis divided into northern includingNara cityand southern includingTotsukawa.The northern dialect, sometimes calledNara-ben(Nại lương biện) orYamato-ben( đại hòa biện ), has a few particularities such as an interjectory particlemiias well asnaa,but the similarity with Osaka-ben increases year by year because of the economic dependency to Osaka. On the other hand, southern Nara prefecture is alanguage islandbecause of its geographic isolation with mountains.The southern dialectuses Tokyo type accent, has the discrimination of grammatical aspect, and does not show a tendency to lengthen vowels at the end of monomoraic nouns.

Example

[edit]An example of Kyoto women's conversation recorded in 1964:

| Original Kyoto speech | Standard Japanese | English |

|---|---|---|

| Daiichi, anta kyoo nande? Monossugo nagai koto mattetan e. | Daiichi, anata kyoo nande? Monosugoku nagai koto matteita no yo. | In the first place, today you... what happened? I've been waiting for a very long time. |

| Doko de? | Doko de? | Where? |

| Miyako hoteru no ue de. Ano, robii de. | Miyako hoteru no ue de. Ano, robii de. | At the top of the Miyako hotel. Uh, in the lobby. |

| Iya ano, denwa shitan ya, honde uchi, goji kitchiri ni. | Iya ano, denwa shitan da, sorede watashi, goji kitchiri ni. | Well, I called, just at 5 o'clock. |

| Okashii. Okashii na. | Okashii. Okashii na. | That's strange. Isn't that strange? |

| Hona tsuujihinkattan ya. | Jaa tsuujinakattan da. | And I couldn't get through. |

| Monosugo konsen shiteta yaro. | Monosugoku konsen shiteita desho. | The lines must have gotten crossed. |

| Aa soo ya. | Aa soo da yo. | Yes. |

| Nande yaro, are? | Nande daroo, are? | I wonder why? |

| Shiran. Asoko denwadai harootaharahen no chaunka te yuutetan e. Ookii shi. | Shiranai. Asoko denwadai o haratteinain janainoka tte itteita no yo. Ookii shi. | I don't know. "Maybe they haven't paid for the phone," I said. Because it's a big facility. |

| Soo ya. Mattemo mattemo anta kiihin shi, moo wasureteru shi, moo yoppodo denwa shiyo kana omotan ya kedo, moo chotto mattemiyo omotara yobidasahattan. | Soo da yo. Mattemo mattemo anata konai shi, moo wasureteiru shi, moo yoppodo denwa shiyoo kana to omottan da kedo, moo chotto mattemiyoo to omottara yobidashita no. | Yes. Even after I waited for a long time, you didn't come, so I thought you'd forgotten, so I thought about calling you, but just when I'd decided to wait a little longer the staff called my name. |

| Aa soo ka. Atashi. Are nihenme? Anta no denwa kiitan. | Aa soo. Watashi. Are nidome? Anata ga denwa o kiita no. | Is that so. I... Was it the second time when you heard about the phone? |

| Honma... Atashi yobidasaren no daikirai ya. | Honto.... Watashi yobidasareru no daikirai da. | Really, I hate having my name called out. |

| Kan'nin e. | Gomen ne. | Sorry. |

| Kakkowarui yaro. | Kakkowarui desho. | It's awkward, right? |

See also

[edit]Kansai dialect in Japanese culture

[edit]- Bunraku- a traditional puppet theatre played in Osaka dialect during the Edo period

- Kabuki- Kamigata style kabuki is played in Kansai dialect

- Rakugo- Kamigata style rakugo is played in Kansai dialect

- Mizuna-mizunais originally a Kansai word for Kanto wordkyōna

- Shichimi-shichimiis originally a Kansai word for Kanto wordnanairo

- Tenkasu-tenkasuis originally a Kansai word for Kanto wordagedama

- Hamachi-hamachiis originally a Kansai word for Kanto wordinada[16]

Related dialects

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Omusubi: Japan's Regional DiversityArchived2006-12-14 at theWayback Machine,retrieved January 23, 2007

- ^abMitsuo Okumura (1968).Kansaiben no chiriteki han'i(Quan tây biện の địa lý đích phạm 囲).Gengo seikatsu(Ngôn ngữ sinh hoạt)202 number. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo.

- ^Fumiko Inoue (2009).Kansai ni okeru hōgen to Kyōtsūgo(Quan tây における phương ngôn と cộng thông ngữ).Gekkan gengo(Nguyệt khan ngôn ngữ)456 number. Tokyo: Taishukan Shoten.

- ^Masataka Jinnouchi (2003).Studies in regionalism in communication and the effect of the Kansai dialect on it.

- ^abUmegaki (1962)

- ^Đại phản biện hoàn toàn マスター giảng tọa đệ tam thập tứ thoại よろがわ[Osaka-ben perfect master lecture No. 34 Yoro River] (in Japanese). Osaka Convention Bureau. Archived fromthe originalon March 20, 2016.RetrievedJuly 19,2015.

- ^NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute (1998). NHK nhật bổn ngữ phát âm アクセント từ điển(NHK Nihongo Hatsuon Akusento Jiten).pp149-150.ISBN978-4-14-011112-3

- ^"Congo word 'most untranslatable'".BBC News.June 22, 2004.RetrievedSeptember 19,2011.

- ^Osamu Matsumoto (1993). Toàn quốc アホ・バカ phân bố khảo ―はるかなる ngôn diệp の lữ lộ(Zenkoku Aho Baka Bunpu-kō).ISBN4872331168

- ^Kazuo Fudano (2006).Ōsaka "Honmamon" Kōza(Đại phản biện “ほんまもん” giảng tọa).Tokyo: Shinchosha

- ^Isamu Maeda (1977).Ōsaka-ben(Đại phản biện).Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun

- ^Riichi Nakaba (2005).Kishiwada Shonen Gurentai.Kodansha.ISBN4-06-275074-0

- ^abRyoichi Sato ed (2009). Đô đạo phủ huyện biệt toàn quốc phương ngôn từ điển(Todōfuken-betsu Zenkoku Hōgen Jiten).

- ^Nobusuke Kishie and Fumiko Inoue (1997). Kinh đô thị phương ngôn の động thái(Kyōto-shi Hōgen no Dōtai)

- ^Kayoko Tsuji (2009). “ハル” kính ngữ khảo kinh đô ngữ の xã hội ngôn ngữ sử(Haru Keigo-kō Kyōto-go no Shakaigengo-shi).ISBN978-4-89476-416-3.

- ^"Yellowtail - Sushi Fish".Sushiencyclopedia.RetrievedMarch 14,2016.

Bibliography

[edit]For non-Japanese speakers, learning environment of Kansai dialect is richer than other dialects.

- Palter, DC and Slotsve, Kaoru Horiuchi (1995).Colloquial Kansai Japanese: The Dialects and Culture of the Kansai Region.Boston: Charles E. Tuttle Publishing.ISBN0-8048-3723-6.

- Tse, Peter (1993).Kansai Japanese: The language of Osaka, Kyoto, and western Japan.Boston: Charles E. Tuttle Publishing.ISBN0-8048-1868-1.

- Takahashi, Hiroshi and Kyoko (1995).How to speak Osaka Dialect.Kobe: Taiseido Shobo Co. Ltd.ISBN978-4-88463-076-8

- Minoru Umegaki (Ed.) (1962). Cận kỳ phương ngôn の tổng hợp đích nghiên cứu(Kinki hōgen no sōgōteki kenkyū).Tokyo: Sanseido.

- Isamu Maeda (1965). Thượng phương ngữ nguyên từ điển(Kamigata gogen jiten).Tokyo: Tokyodo Publishing.

- Kiichi Iitoyo, Sukezumi Hino, Ryōichi Satō (Ed.) (1982). Giảng tọa phương ngôn học 7 - cận kỳ địa phương の phương ngôn -(Kōza hōgengaku 7 -Kinki chihō no hōgen-).Tokyo: Kokushokankōkai

- Shinji Sanada, Makiko Okamoto, Yoko Ujihara (2006). Văn いておぼえる quan tây ( đại phản ) biện nhập môn(Kiite oboeru Kansai Ōsaka-ben nyūmon).Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo Publishing.ISBN978-4-89476-296-1.

External links

[edit]- Kansai Dialect Self-study Site for Japanese Language Learner

- The Corpus of Kansai Vernacular Japanese

- The Kansai and Osaka dialects- nihongoresources.com

- Kansai Ben- TheJapanesePage.com

- Kansai Japanese Guide- Kansai-ben texts and videos made byRitsumeikan Universitystudents

- Osaka-ben Study Website,Kyoto-ben Study Website- U-biq

- A Course in Osaka-ben- Osaka city