Kerala model

TheKerala modelrefers to the practices adopted by theIndianstate ofKeralato further human development. It is characterised by results showing strong social indicators when compared to the rest of the country such as high literacy and life expectancy rates, highly improved access to healthcare, and low infant mortality and birth rates. Despite having a lower per capita income, the state is sometimes compared todeveloped countries.[1]These achievements along with the factors responsible for such achievements have been considered characteristic results of the Kerala model.[1][2]Academic literature discusses the primary factors underlying the success of the Kerala model as its decentralization efforts, the political mobilization of the poor, and the active involvement of civil society organizations in the planning and implementation of development policies.[3]

More precisely, the Kerala model has been defined as:

- A set of high materialquality of lifeindicators coinciding with low per-capita incomes, both distributed across nearly the entire population of Kerala.

- A set ofwealth and resource redistributionprogrammes that have largely brought about the high material quality-of-life indicators.

- High levels ofpolitical participationandactivismamong ordinary people along with substantial numbers of dedicated leaders at all levels. Kerala's mass activism and committed cadre are able to function within a large democratic structure, which their activism has served to reinforce.

History[edit]

The Kerala model originally differed from conventional development thinking which focuses on achieving highGDPgrowth rates, however, in 1990,PakistanieconomistMahbub ul Haqchanged the focus ofdevelopment economicsfromnational incomeaccounting to people centered policies. To produce theHuman Development Report(HDRs), Haq brought together a group of well-known development economists including:Paul Streeten,Frances Stewart,Gustav Ranis,Keith Griffin,Sudhir Anand, andMeghnad Desai.[4][5]

Economists have noted that despite low income rates, the state had high literacy rates, healthy citizens, and a politically active population. Researchers began to delve more deeply into what was going in the Kerala model, since human development indices seemed to show a standard of living which was comparable with life in developed nations, on a fraction of the income. The development standard in Kerala is comparable to that of many first world nations, and is widely considered to be the highest in India at that time.[6]

Despite having high standards of human development, the Kerala model ranks low in terms of industrial and economic development. The high rate of education in the region has resulted in a brain drain, with many citizens migrating to other parts of the world for employment. The job market in Kerala is forcing many to relocate to other places.

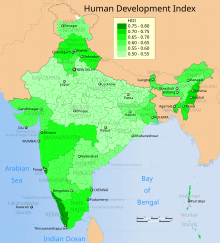

Human Development Index[edit]

The United Nations developed theHuman Development Index(HDI) in 1990 as a composite statistic used to rank countries by level of "human development" and separate developed (high development), developing (middle development), and underdeveloped (low development) countries. The HDI is used in the United Nations Development Programme's annual Human Development Reports and is composed from data on life expectancy, education and per-capita GDP (as an indicator of Standard of living) collected at the national level using a formula. This index, which has become one of the most influential and widely used indices to compare human development across countries, gave the Kerala model international recognition since Kerala has consistently had scores comparable to developed countries since the HDI's inception.[7][8]

In 2021, Kerala again tops the HDI among the Indian states with a score of 0.782, according to the Global Data Lab.[9]

Public health[edit]

History[edit]

Kerala's improved public health relative to other Indian states and countries with similar economic circumstances is founded on a long history of successful health-focused policies.[12][13]

One of the first key strategies Kerala implemented was making vaccinations mandatory for public servants, prisoners, and students in 1879 prior to Kerala becoming a state, when it was composed of autonomous territories. Moreover, the efforts of missionaries in setting up hospitals and schools in underserved areas increased access to health and education services.[12][14]Though class andcastedivisions were rigid and oppressive, a rise in subnationalism in the 1890s resulted in the development of a shared identity across class and caste groups and support for public welfare. Simultaneously, the growth in agriculture and trade in Kerala also stimulated government investment in transportation infrastructure. Thus, leaders in Kerala began increasing spending on health, education, and public transportation, establishing progressive social policies. By the 1950s, Kerala had a significantly higher life expectancy than neighboring states as well as the highest literacy rate in India.[12][15]

Once Kerala became a state in 1956, public scrutiny of schools and health care facilities continued to increase, along with residents' literacy and awareness of the necessity of access health services. Gradually, health and education became top priorities, which was unique to Kerala according to a local public health researcher.[12][16]The state's high minimum wages, road expansion, strong trade and labor unions, land reforms, and investment in clean water, sanitation, housing, access to food, public health infrastructure, and education all contributed to the relative success of Kerala's public health system.[12][17]In fact, declining mortality rates during this time period doubled the state's population,[12][18]and immunization services, infectious disease care, health awareness activities, and antenatal and postnatal services became more widely available.[12][17]In the 1970s, a decade before India initiated its national immunization program withWHO,Kerala launched an immunization program for infants and pregnant women.[12][19]In addition, smaller private medical institutions complemented the government's efforts to increase access to health services and provided specialized healthcare.[12][20]As a result, life expectancy continued to increase in Kerala, though household income remained low.[12][21]Thus, the concept of the "Kerala model" was coined by development researchers in Kerala in the 1970s and the state received international recognition for its health outcomes despite a relatively low per capita income.[12][22]

In the mid-1970s to the early 1990s, a fiscal crisis caused the government to reduce spending on health and other social services. Reductions in federal health spending also affected Kerala's health budget.[12][14]As a result, the quality and abilities of public healthcare facilities declined and residents protested.[12][23]Eventually, private health services began to take over, enabled by a lack of government regulation. In fact, by the mid-1980s, only 23% of households regularly utilized government health services, and from 1986 to 1996, private-sector growth significantly surpassed public-sector growth.[12][14][20]

In 1996, Kerala began to decentralize public healthcare facilities and fiscal responsibilities to local self-governments by implementing the People's Campaign for Decentralized Planning in response to public distrust and national recommendations.[12][13][19]For instance, new budgetary allocations gave local governments control of 35 to 40% of the state budget. Moreover, the campaign emphasized improving care and access, regardless of income level, caste, tribe, or gender, reflecting a goal of not just effective but also equitable coverage.[13][24]A three-tier system of self-governance was established, consisting of 900panchayats(villages), 152 blocks, and 14 districts.[13][25]The current healthcare system arose from local self-governments supporting the construction of sub-centers, primary health centers that support five to six sub-centers and serve a village, and community health centers.[13]The new system also allowed local self-governments to create hospital management committees and purchase necessary equipment.[12][19]

Present[edit]

The basis for the state's health standards is the state-wide infrastructure of primary health centers.[26]Under the current system, the primary health centers and sub-centers were brought under the jurisdiction of local self-governments to respond to local health needs and work more closely with local communities.[13][25]As a result, health outcomes and access to healthcare services have improved.[13][24]There are over 9,491 government and private medical institutions in the state, which have about 38000 beds for the total population, making the population to bed ratio 879—one of the highest in the country.[27][10]

There is an active, state-supported nutrition programme for pregnant and new mothers and about 99% of child births are institutional/hospital deliveries,[28]leading to infant mortality in 2018 being 7 per thousand,[29]compared to 28 in India, overall[30]and 18.9 for low- middle income countries generally.[31]The birth rate is 40 percent below that of the national average and almost 60 percent below the rate for impoverished countries in general. Kerala's birth rate is 14.1[32](per 1,000 people) and decreasing. India's rate is 17[33]the rate of the U.S. is 11.4.[34]Life expectancyat birth in Kerala is 77 years, compared to 70 years in India[35]and 84 years in Japan,[36]one of the highest in the world. Female life expectancy in Kerala exceeds that of the male, similar to that in developed countries.[37]Kerala's maternal mortality ratio is the lowest in India at 53 deaths per 100,000 live births.[35]

According to theIndia State Hunger Index,in 2009, Kerala was one of the four states where hunger was only moderate. The hunger index score of Kerala was 17.66 and was second only to Punjab, the state with the lowest hunger index. The nationwide hunger index of India was 23.31.[38]Despite the fact that Kerala has a relatively low dietary intake of 2,200 kilocalories per day, the infant-mortality rate and the percentage of the population facing severe undernutrition in Kerala is far lower than in other Indian states. In early 2000, more than a quarter of the population faced severe undernutrition in three states—Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh—though they had a higher average dietary intake than Kerala. Kerala's improved nutrition is primarily due to better healthcare access as well as greater equality in food distribution across different income groups and within families.[3]

| Medical Colleges | 34 |

| Hospitals | 1280 |

| Community Health Centres[10] | 229 |

| Primary Health Centres[10] | 933 |

| Sub Centres | 5380 |

| AYUSH Hospitals/Dispensary | 162/1473 |

| Total Beds | 38004 |

| Blood Banks | 169 |

District-wise Hospital Bed Population Ratio as per the 2011[39]

| District | Population Census(2011) | Number of beds | Population Bed Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alappuzha | 2127789 | 3424 | 621 |

| Ernakulam | 3282388 | 4544 | 722 |

| Idukki | 1108974 | 1096 | 1012 |

| Kannur | 2523003 | 2990 | 844 |

| Kasaragod | 1307375 | 1087 | 1203 |

| Kollam | 2635375 | 2388 | 1104 |

| Kottayam | 1974551 | 2817 | 701 |

| Kozhikode | 3086293 | 2820 | 1094 |

| Malappuram | 4112920 | 2503 | 1643 |

| Palakkad | 2809934 | 2622 | 1072 |

| Pathanamthitta | 1197412 | 1948 | 615 |

| Thiruvananthapuram | 3301427 | 4879 | 677 |

| Thrissur | 3121200 | 3519 | 887 |

| Wayanad | 817420 | 1367 | 598 |

| Total | 33406061 | 38004 | 879 |

The Health Index, ranking the performance of the States and the Union Territories in India in Health sector, published in June 2019 by the NITI Ayong, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and The World Bank has Kerala on top with an overall score of 74.01.Kerala has already achieved the SDG 2030 targets for Neonatal Mortality Rate, Infant Mortality Rate, Under-5 Mortality rate and Maternal Mortality Ratio.[40][41][42]

The Economist has recognized the Kerala government for providing palliative care policy (it is the only Indian state with such a policy) and funding for community-based care programmes. Kerala pioneereduniversal health carethrough extensive public health services.[43][44]Hans Roslingalso highlighted this when he said Kerala matches U.S. in health but not in economy and took the example ofWashington, D.C.which is much richer but less healthy compared to Kerala.[45][46]

Key Health Development indicators-Kerala & India

| Health Indicators | Kerala | India |

|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy at birth (Male)[35] | 74.39 | 69.51 |

| Life expectancy at birth (Female)[35] | 79.98 | 72.09 |

| Life expectancy at birth (Average)[35] | 77.28 | 70.77 |

| Birth rate (per 1,000 population) | 14.1[32] | 17.64[33] |

| Death rate (per 1,000 population) | 7.47[32] | 7.26[33] |

| Infant mortality rate (per 1,000 population) | 7[29] | 28[30] |

| Under 5-Mortality rate(per 1,000 live births)[28] | 10 | 36 |

| Maternal mortality ratio (per lakh live births)[35] | 53.49 | 178.35 |

| Indicators | 2020 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| Children in the age group 9–11 months Immunised(%) | 92 | |

| Notification rate of Tuberculosis per 1,00,000 population | 75 | 71 |

| HIV Incidence per 1,000 uninfected population | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Suicide rate (per 1,00,000 population) | 24.30 | |

| Death rate due to road accidents per 1,00,000 population | 12.42 | |

| Institutional deliveries out of the total deliveries reported (%) | 99.90 | 74 |

| Monthly per capita out-of-pocket expenditure on health (%) | 17 | |

| Physicians, nurses and midwives per 10,000 population | 115 | 112 |

Education[edit]

Pallikkoodam,a school model started by Buddhists was prevalent in theMalabar region,Kingdom of Cochin,and Kingdom ofTravancore.This model was later acquired by Christian missionaries and paved the way for an educational revolution in Kerala by making education accessible to all, irrespective of caste or religion. Christian missionaries introduced Western education methods to Kerala. Communities such as Ezhavas, Nairs and Dalits were guided by monastic orders (calledashrams) and Hindu saints and social reformers such asSree Narayana Guru,Sree Chattampi SwamikalandAyyankali,who exhorted them to educate themselves by starting their own schools. That resulted in numerous Sree Narayana schools and colleges,Nair Service Societyschools. The teachings of these saints have also empowered the poor and backward classes to organize themselves and bargain for their rights. TheGovernment of Keralainstituted theAided Schoolsystem to help schools with operating expenses such as salaries for running these schools.[citation needed]

Kerala had been a notable centre ofVediclearning, having produced one of the most influential Hindu philosophers,Adi Shankaracharya.The Vedic learning of theNambudirisis an unaltered tradition that still holds today, and is unique for its orthodoxy, unknown to other Indian communities. However, in feudal Kerala, though only the Nambudiris received an education inVedas,other castes as well as women were open to receive education inSanskrit,mathematics andastronomy,in contrast to other parts of India.[citation needed]Tirunavayawas a centre of Vedic learning in early medieval period.Ponnaniin Kerala was a global centre ofIslamiclearning during the medieval period.

The upper castes, such asNairs,Tamil Brahmin,Ambalavasis,St Thomas Christians,as well as lower castes such asEzhavashad a strong history of Sanskrit learning. In fact, manyAyurvedicphysicians (such asItty Achudan) were from the lower-casteEzhavacommunity andMuslimcommunity (such as the father of renownedMappila PaattupoetMoyinkutty Vaidyar).Vaidyaratnam P. S. Warrierwas a prominent Ayurvedic physician. This level of learning by lower-caste people was not seen in other parts of India. Also, Kerala had been the site of the notableKerala Schoolwhich pioneered principles of mathematics and logic, and cemented Kerala's status as a place of learning.[citation needed]

The prevalence of education was not only restricted to males. In pre-colonial Kerala, women, especially those belonging to thematrilinealNaircaste, received an education in Sanskrit and other sciences, as well asKalaripayattu,a martial art. This was unique to Kerala, but was facilitated by the inherent equality shown by Kerala society to females and males,[citation needed]since Kerala society was largely matrilineal, as opposed to the rigid patriarchy in other parts of India which led to a loss of women's rights.[citation needed]

The rulers of the princely state ofTravancorealso were at the forefront in the spread of education. A school for girls was established by the Maharaja in 1859, which was an act unprecedented in the Indian subcontinent. In colonial times, Kerala exhibited little defiance against theBritish Raj.However, they had mass protests forsocial causessuch as rights for "untouchables"and education for all. Popular protest to hold public officials accountable is a vital part of life in Kerala.[47]

The following table shows the literacy rate of Kerala from 1951 to 2011, measured every decade:[48]

| Year | Literacy | Male | Female | Transgender/ Non-binary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 47.18 | 58.35 | 36.43 | |

| 1961 | 55.08 | 64.89 | 45.56 | |

| 1971 | 69.75 | 77.13 | 62.53 | |

| 1981 | 78.85 | 84.56 | 73.36 | |

| 1991 | 89.81 | 93.62 | 86.17 | |

| 2001 | 90.92 | 94.20 | 87.86 | |

| 2011 | 94.59 | 97.10 | 92.12 | 84.61[49] |

TheKerala State Literacy Mission Authority(KSLMA) had set up "continuing education programmes fortransgenders"(Samanwaya) to educate transgender people in Kerala who are ostracised by their family and society and "forced to go out of homes as they are harassed in schools, colleges and in society".[50][51]The Social Justice Department of Kerala has various welfare programmes for transgender people likeYatnam[52]which provides financial assistance for transgender students preparing for competitive exams,Varnamfor distance education programmes, there are also other financial assistant programmes for hostel facility[53]etc.[54][55][56]Although these policies help some of the transgender people positively they still face disproportionate amount of discrimination in their daily life which makes it harder for these policies to have a meaningful impact on the transgender community.[57][58][59][60]

Gender[edit]

Kerala has the highest score on theGender Development indexin India, as demonstrated by the relatively high literacy rate, sex ratio, and mean age at marriage for women, as well as low fertility and infant mortality rates compared to the rest of the country.[61][62][63][64]In fact, women in Kerala have played a crucial role in increasing the state's literacy rates, with the mobilization of educated, unemployed women making up two-thirds of volunteer teachers involved in the literacy drive during a 1990 campaign to eliminate illiteracy.[64]The literacy gap between males and females in India is lowest in Kerala, with the female literacy rate just 5% lower than that of males.[48]Moreover, as of 2021, the life expectancy for females is 79.98 years in Kerala compared to 72.09 years in India as a whole.[35]The infant mortality rate is 7 per 1,000 live births in Kerala,[29]as opposed to 28 in India.[30]Another indicator of gender equality and women's health is thematernal mortalityrate, which is 53.59 per 100,000 live births in Kerala and 178.35 in the rest of India.[35]

Historically, women in Kerala are thought to have possessed more autonomy relative to other Indian states, which is often attributed to itsmatrilinealstructure which ultimately changed into apatrilinealsystem in the 20th century.[65][66][67][64][68]Matriliny, in which property was inherited collectively through the female line, was largely practiced by the Hindu Nair caste as well as some other upper-caste Hindus such as the Ezhavas and even some Muslims, who are exclusively patriarchal in other parts of India.[64][68]However, Christian succession laws in the early 20th century in Kerala were severely restrictive against women. For instance, unmarried daughters could only claim between a quarter and a third of each son's share of paternal property, or 5,000 rupees, whichever was less, if the father died without making a will. In all other instances, daughters' inheritances were restricted to dowries. These laws were challenged whenMary Roy,aSyrian Christianwoman who had not received adowrysued her brother to gain equal access to their inheritance. She ultimately won the case and it was considered a landmark ruling for female succession. Beginning in the 1920s, the Hindu matriarchal system fragmented, especially once the Travancore Nayar Regulation Act of 1925 was passed, which was initiated by the British and began the transition to a strictly patriarchal structure.[64]By the 1970s, the matrilineal system had virtually disappeared and the Kerala family organization became exclusively patrilineal and women's rights to property were significantly restricted.[68]

Though women in Kerala are highly educated, recent studies have called attention to the "gender paradox" in Kerala, in which despite the literacy and education of women in Kerala, they are still oppressed in similar or greater regards by the patriarchy relative to other Indian states.[62][65]Societal and cultural norms are argued by scholars to continue to restrict women's freedoms and maintain their subservience to men both at home and in the labor market. High female unemployment rates, discrimination in the labor market, and elevated female suicide rates and gender-based violence, are all indicators of the "gender paradox" in Kerala.[62][64]In addition, the persistence of the long-standing tradition of dowry across lines of caste, class, and religion, and the finding that women do about twenty times as much housework as men in Kerala suggest the restricted autonomy and oppression that Kerala women continue to face.[64][69]Furthermore, economic participation and involvement of women is declining in Kerala, and male casual laborers receive almost double that of women.[70]However, some policies such as theMahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme(MGNREGS) andKudumbashreemicroenterprises have promoted female entrepreneurship, encouraged women's economic empowerment, and decreased gender disparities in Kerala, according to academic literature analyzing gender sensitive policies.[71]

State policy[edit]

In 1957 Kerala elected a communist government headed byEMS Namboothiripad,introduced the revolutionaryLand Reform Ordinance.The land reform was implemented by the subsequent government, which had abolishedtenancy,benefiting 1.5 million poor households. This achievement was the result of decades of struggle by Kerala's peasant associations. In 1967 in his second term asChief Minister,EMS again pushed for reform. The land reform initiative abolished tenancy andlandlordexploitation, effectivepublic food distributionthat provides subsidised rice to low-income households, protective laws for agricultural workers, pensions for retired agricultural laborers, and a high rate of government employment for members of formerlylower-castecommunities.[citation needed]

Indiais a multinational state home to provincial states with differing policies, and Kerala's place within thisfederalistsystem can be seen through analyses of itsregime type.Two coalitions containing all-India parties have alternately been in power in Kerala—not dissimilar to the neighboring South Indian state ofAndhra Pradesh.Kerala has a strongleftistmovement presence that has contributed to changes in the traditionalfeudal-castesystem in India.Democratizationof the state has surrounded significant increases in components ofwelfareand has led to a large social transformation since the early 20th century.[72]

Kerala andTamil Naduhave comparable increases in social development, albeit with Kerala to a much higher degree—yet Tamil Nadu has been ruled by Tamilnationalistparties for over half a century.[73]In comparison,West Bengalis seen as even stronger in terms of Leftist movement and governmental policy compared to Kerala yet is ranked far lower in disparities in rural areas, urban areas,scheduled castes, and scheduled tribes.Further, there is hardly any per capita consumption expenditure andliteracy levelsbetween Muslims and Hindus in Kerala—while Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, and the country as a whole have relatively high levels of disparities among the two predominant religious groups.[73]

Interestingly enough, those political radicals involved in the original social integration movements in Kerala were politically conservative. Nonetheless, the social discrimination due to caste of the early 20th century contributed to the cultural revolt andpolitical mobilizationof depressed castes. It was the success of these movements that allowed for the creation of Leftist movements that elevates the social status of lower classes as a whole.[74]

Gaps in the Kerala Model[edit]

Kerala has had consistently high levels of development when compared to the rest of the country. The state has the highest record of per capita consumer expenditure, and this level has been progressively increasing since 1993.[73]Kerala has now begun a high growth regime driven mainly by its service and construction industries. The all-India and statewise trend in the estimates of poverty headcount ratio (HCR) andGini coefficientshow that Kerala reduced its HCR by 10.3% between 1988-1993 and then again by another 12.2% in the 11 years proceeding until 2004–2005. Comparatively,Himachal Pradesh—which did not benefit from the same Gulf boom that Kerala did—reduced its post-reformrural povertyto a lower HCR of 10.9% in 2004–05. Moreover, though there was a marginal decline in the Gini coefficient for rural Kerala in 1993-1994 compared to previous years, there is a jump to 38.3% in 2004-2005—the highest figure compared to all-India figures and all other states. The urban Gini coefficient for Kerala in 2004-05 was 41%, second only to Chhattisgarh. Comparisons of scheduled tribes, castes, and religions also show growing income disparities, reflected by increasing incidence of suicides, family violence, gang activity, and alcoholism, among others.[75]

Even public provisioning of equitable access to healthcare and education, which are the foundation of the Kerala model, have decreased overall. The percentage ofpublic spendingon education to total government expenditure decreased from 29.28% in 1982–83 to 23.17% 1992-93 and 17.97% in 2005–06.[74]In terms of education, the educational expenditure size of 6% which Kerala followed in the 1960s and 70s declined to just over 4% in the 1980s and below that in 11 of the 16 years during the post-reform regime. While decline of public expenditure on education decreased during the pre-reform period (from 1980 to 1991) at a rate of 0.97% yearly, the post-reform period has seen an even sharper decline of 2.13% a year. With regard to public expenditure on health and family welfare, there too has been an equally sharp fall in spending, from 11.67% ofstate domestic product(SDP) to 1983–84 to 9.94% in 1989-90 and down to 6.36% in 2005–06.Social securityentitlements as a percentage of SDP fell significantly too, while it was increasing at a rate of 1.83% in the pre-reform period it fell to 0.15% during the reform period. Under the currentneoliberalregime there has been accelerated commercialization of the education and health sectors—which has altered the equity base of the Kerala model as a whole.[73]For example, the proportion of students atprivate unaided schoolsrose from 2.5% of the 5.9 million total student population in 1990–91 to 7.4% in 2005-06. This is coupled with a 7.5% of intake in government schools over the same time, and only those with the means to pay high fees can go to these private unaided schools.[75]

Themarine fishery sectorin Kerala is an example of the extent to which disparities still exist despite the Kerala Model's emphasis placed onequality.Though fish and fisheries have a very significant place within Kerala as a whole, fishing communities in Kerala have not benefited from state's overall efforts at improving quality of life nor the increased value of output in the sector. Data from 1965 to 1975 indicate an eleven-fold increase in the value of output from Rs 68.5 million to 741.4 million in current prices.[76]However, a major deceleration in the rate of increase of value of output is observed from 1975 to 1985 where the level grew from Rs 741.4 million to just Rs 906.4 million as a result of declining fish harvests and prices. While the net state domestic product has increased by about 18% in the same decade, the fishery sector product has decreased by 20% in comparison. This can be seen in the 29% increase in the gap between per capita state domestic product and product per fisherperson between 1975–76 and 1984–85.[76]Povertyis also prevalent in marine fishing communities that are often located on the geographical margins of the land who depend exclusive on the sea for their livelihood. These and other communities on the fringe of state borders have been left behind in the economic and socio-cultural progress that has been widely witnessed by the rest of the state. Poorquality of lifeand substandard conditions in marine fishing communities can be attributed specifically to the crowding of entire groups of people on the narrow strip of line along the length of Kerala's coastline: a total of 222 fishing villages along the state's 590 km coastline—none more than a half kilometer wide.[75]Population densityin marine fishing villages was measured to be around 2113 persons per square kilometer in 1981, compared to a state figure of 655 per square kilometer. Basic amenities such as electric lighting, access to running water, toilet facilities, etc. are also at far lower standards in these fishing villages when compared to the state as a whole. The lack of basic facilities andhygienehas led to rapid spread ofcontagious diseasesin these areas which express high levels of respiratory and skin infections, diarrheal disorders and hook worm infections to state a few. Though the all-Keralainfant mortality ratewas 17 per 1000 live births in 1991, the corresponding rate is 85 per 1000 births in marine fishing communities. There is also a clear gender bias evidenced by the sex ratio of 972 females to 1000 males in these communities, compared to the all-Kerala 1084:1000 ratio of females to males. Thus, marine fishing communities clearly represent an outlier community that has faced restricted levels of capabilities while the state of Kerala has seen progress overall.[76]

Opinions[edit]

British Green activistRichard Douthwaiteinterviewed a person who remembers once saying that "in some societies, very high levels – virtually First World levels – of individual and public health and welfare are achieved at as little as sixtieth of US nominal GDP per capita and used Kerala as an example".[77]: 310–312 Richard Douthwaite states that Kerala "is far more sustainable than anywhere in Europe or North America".[78]Kerala's unusual socioeconomic and demographic situation was summarized by author and environmentalistBill McKibben:[79]

Kerala, a state in India, is a bizarre anomaly among developing nations, a place that offers real hope for the future of the Third World. Though not much larger than Maryland, Kerala has a population as big as California's and a per capita annual income of less than $3000. But its infant mortality rate is very low, its literacy rate's among the highest on Earth, and its birthrate's below that of America's and falling faster. Kerala's residents live nearly as long as Americans or Europeans. Though mostly a land of paddy-covered plains, statistically Kerala stands out as the Mount Everest of social development; there's truly no place like it.[79]

Kerala continues to leadlow-income areascompared to the rest of India. Recent criticisms of the Kerala Model suggest that Kerala is losing its lead within India. K. K. George cites figures indicating that Punjab spends more per capita on education and that bothRajasthanandPunjabspend more per capita on health than Kerala. He also compares Kerala unfavorably withMaharashtra,Haryana,Madhya Pradesh,Nagaland,Rajasthan, andUttar Pradeshin pension payments todestitutes.These weaknesses should not be overlooked, but they remain minor compared with Kerala's continuing overall ability to deliver a high material quality of life to its people as the indicators show. Oommen and Anandaraj district-level profile (1996) found 9 of Kerala's 14 districts among the top 12 in all of India on a composite ofliteracy,life expectancy,and several economic variables. Kerala's lowest district ofMalappuramwas 31st on a list of 372 districts.[80]

The liberalization-cum-structural adjustment package of the Fund and the Bank presents a philosophy that asserts that the working masses need to make sacrifices today for the sake of providing incentives tocapitalistsfor higher growth, from which those sameworkerswould benefit later. This ‘trickle down’ effect emphasizes the means augmentingsupply-sidemeasures necessary for the success of the Kerala Model. Thus, there is an argument that Kerala itself is not self-sufficient but part of a larger region which has this characteristic. The ‘reforms’ observed, then, are more of a reflection of the structural changes made by theIndian economywhich has increased supply sideincentivesfor capitalists. This has led to a rise in the degree ofexploitationof the working people by cutting their so-calledsocial wageand wrecking the internal balance of the production-structure, which should be taken into consideration when looking at the Kerala Model as a worthwhile example for otherthird worldstates.[81]

References[edit]

- ^abParayil, Govindan (2000)."Introduction: Is Kerala's Development Experience a Model?".In Govindan Parayil (ed.).Kerala: The Development Experience: Reflections on Sustainability and Replicability.London: Zed Books.ISBN1-85649-727-5.Retrieved16 January2011.

- ^Franke, Richard W.; Barbara H. Chasin (1999)."Is the Kerala Model Sustainable? Lessons from the Past, Prospects for the Future".InM. A. Oommen(ed.).Rethinking Development: Kerala's Development Experience, Volume I.New Delhi: Institute of Social Sciences.ISBN81-7022-764-X.Retrieved16 January2011.

- ^abBanik, Dan (2011)."Poverty, Inequality, and Democracy: Growth and Hunger in India".Journal of Democracy.22(3): 90–104.doi:10.1353/jod.2011.0049.ISSN1086-3214.S2CID153698245.

- ^"Kerala Model & development".Dawn.com. Archived fromthe originalon 13 April 2010.Retrieved17 July2010.

- ^"KN Raj passes away".Oman Tribune. Archived fromthe originalon 15 July 2011.Retrieved17 July2010.

- ^Parayil, Govindan (December 1996)."The 'Kerala model' of development: Development and sustainability in the Third World".Third World Quarterly.17(5): 941–958.doi:10.1080/01436599615191.ISSN0143-6597.PMID12321040.

- ^"Human Development Index rose 21 per cent; Kerala tops chart".CNBC.21 October 2011.

- ^"HDI in India rises by 21%: Kerala leads the race".FirstPost. 21 October 2011.

- ^"Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab".globaldatalab.org.Retrieved13 September2021.

- ^abcd"Hospitals in the Country".pib.gov.in.Retrieved14 September2021.

- ^"Government Medical College,Thiruvananthapuram".tmc.kerala.gov.in.Retrieved14 September2021.

- ^abcdefghijklmnopMadore, Amy; Rosenberg, Julie; Dreisbach, Tristan; Weintraub, Rebecca (2018)."Positive Outlier: Health Outcomes in Kerala, India over Time".www.globalhealthdelivery.org.Retrieved1 May2022.

- ^abcdefg"Kerala, India: Decentralized governance and community engagement strengthen primary care".PHCPI.18 September 2015.Retrieved1 May2022.

- ^abcKutty, V R. (1 March 2000)."Historical analysis of the development of health care facilities in Kerala State, India".Health Policy and Planning.15(1): 103–109.doi:10.1093/heapol/15.1.103.PMID10731241.

- ^Singh, Prerna (2015),"How Subnationalism promotes Social Development",How Solidarity Works for Welfare,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 112–147,doi:10.1017/cbo9781107707177.004,ISBN9781107707177,retrieved1 May2022

- ^Bollini, P.; Venkateswaran, C.; Sureshkumar, K. (2004)."Palliative Care in Kerala, India: A Model for Resource-Poor Settings".Oncology Research and Treatment.27(2): 138–142.doi:10.1159/000076902.ISSN2296-5270.PMID15138345.S2CID3018086.

- ^abBoard., Kerala (India). Bureau of Economic Studies. Kerala (India). Bureau of Economics and Statistics. Kerala (India). State Planning.Kerala; an economic review.[Printed at the Govt. Press].OCLC1779459.

- ^body., Kerala (India). State Planning Board, issuing.Economic review...OCLC5974255.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abcThomas, M. Benson.Decentralisation and interventions in health sector: a critical inquiry into the experience of local self governments in Kerala.OCLC908377268.

- ^abCommission., India. Planning (2008).Kerala development report.Academic Foundation.ISBN978-81-7188-594-7.OCLC154667906.

- ^Board., Kerala (India). State Planning.Economic review, Kerala.State Planning Board, Kerala.OCLC966447651.

- ^Centre for Development Studies, United Nations (1975).Poverty, unemployment and development policy: a case study of selected issues with reference to Kerala.United Nations.OCLC875483852.

- ^"Remittances to Kerala: Impact on the Economy".Middle East Institute.Retrieved1 May2022.

- ^abElamon, Joy; Franke, Richard W.; Ekbal, B. (October 2004)."Decentralization of Health Services: The Kerala People's Campaign".International Journal of Health Services.34(4): 681–708.doi:10.2190/4l9m-8k7n-g6ac-wehn.ISSN0020-7314.PMID15560430.S2CID29112205.

- ^abVaratharajan, D (1 January 2004)."Assessing the performance of primary health centres under decentralized government in Kerala, India".Health Policy and Planning.19(1): 41–51.doi:10.1093/heapol/czh005.ISSN1460-2237.PMID14679284.

- ^"MISSION AND VISION – dhs".Retrieved14 September2021.

- ^abState Health Profile, National Health Authority, Government of India (January 2021)."State Health Profile-Kerala, National Health Authority, Government of India"(PDF).pmjay.gov.in/.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abcPARTNERSHIPS IN THE DECADE OF ACTION, SDG INDIA INDEX AND DASHBOARD 2020-2021 (4 March 2021)."SDG INDIA INDEX AND DASHBOARD 2020-2021-PARTNERSHIPS IN THE DECADE OF ACTION, NITI AYOG 2021"(PDF).www.niti.gov.in.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^abc"Reserve Bank of India - Publications".m.rbi.org.in.Retrieved13 September2021.

- ^abc"Mortality rate, infant (per 1,000 live births) - India | Data".data.worldbank.org.Retrieved13 September2021.

- ^"Mortality rate, neonatal (per 1,000 live births) - Low & middle income | Data".data.worldbank.org.Retrieved14 September2021.

- ^abcReport 2018, Government of Kerala, Annual Vital Statistics (2019)."ANNUAL VITAL STATISTICS REPORT – 2018, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala 2019"(PDF).www.ecostat.kerala.gov.in.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2 November 2021.Retrieved17 October2021.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^abc"Death rate, crude (per 1,000 people) - India | Data".data.worldbank.org.Retrieved13 September2021.

- ^"Birth rate, crude (per 1,000 people) - United States | Data".data.worldbank.org.Retrieved14 September2021.

- ^abcdefgh"GBD India Compare | IHME Viz Hub".vizhub.healthdata.org.Retrieved13 September2021.

- ^"Countries with highest life expectancy 2019".Statista.Retrieved14 September2021.

- ^"Kerala: A case study".Bill McKibben.

- ^"The India State Hunger Index: Comparisons of Hunger Across States"(PDF).2008. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 14 February 2009.

- ^Government of Kerala, Health at a Glance 2018 (2018)."Health at a Glance, 2018- Department of Health, Government of Kerala"(PDF).dhs.kerala.gov.in/.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Report on ranks of States and Union Territories, June 2019, Healthy States Progressive India (June 2019)."Healthy States Progressive India- Report on the Ranks of States and Union Territories, June 2019"(PDF).social.niti.gov.in/.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^"Kerala: the community model (Page No 24)"(PDF).The Economist.Retrieved25 July2010.

- ^"'The Economist' hails Kerala model ".The New Indian Express. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016.Retrieved25 July2010.

- ^"Universal healthcare: the affordable dream".The Guardian.6 January 2015.

- ^Kapur, Akash (1 September 1998)."Poor but Prosperous".The Atlantic.

- ^Rosling, Hans."Transcript of" Asia's rise -- how and when "".www.ted.com.

- ^"The Enigma of Kerala".9 October 2007.

- ^"How almost everyone in Kerala learned to read".The Christian Science Monitor.2005.

- ^ab"Education".Kerala Government. Archived fromthe originalon 26 July 2010.Retrieved17 July2010.

- ^"TransGender/Others - Census 2011 India".www.census2011.co.in.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^"Continuing Education programme for Transgenders".Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^"18 transgenders clear higher secondary course via Kerala's Samanwaya programme".OnManorama.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^"Social Justice, Kerala".sjd.kerala.gov.in.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^"Social Justice, Kerala".sjd.kerala.gov.in.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^"Social Justice, Kerala".sjd.kerala.gov.in.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^"Social Justice, Kerala".sjd.kerala.gov.in.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^"Social Justice, Kerala".sjd.kerala.gov.in.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^"Kerala govt failed in implementing transgender policy: Amicus curiae report".India Today.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^Ajith, Aishwarya (9 October 2022)."Slow But Steady: how Kerala's Transgender Policy has helped the Trans Community".Public Policy India.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^R, Dr Poornima (2022)."Through the Cracks of the Gendered World: A Critical Analysis of Kerala's Transgender Policy".Journal of Polity and Society.14(2).ISSN0976-0210.

- ^"Seven months in, Kerala's transgender policy still thicker on paper than in reality".The News Minute.13 June 2016.Retrieved15 April2023.

- ^Kumar, B. Pradeep (1 December 2020)."Does Gender Status Translate into Economic Participation of Women? Certain Evidence from Kerala"(PDF).Shanlax International Journal of Economics.1(9). Rochester, NY: 50–56.doi:10.34293/economics.v9i1.3546.S2CID229368586.SSRN3785204.

- ^abcMitra, Aparna; Singh, Pooja (December 2007)."Human Capital Attainment and Gender Empowerment: The Kerala Paradox".Social Science Quarterly.88(5): 1227–1242.doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00500.x.ISSN0038-4941.

- ^Parthiban, Dr Shahana A. M., Dr A. Sivakumar & Mr V. (25 June 2021).THE OPPORTUNITIES OF UNCERTAINTIES: FLEXIBILITY AND ADAPTATION NEEDED IN CURRENT CLIMATE Volume I (Social Science and ICT).Lulu Publication.ISBN978-1-300-39724-3.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^abcdefgChacko, Elizabeth (2003)."Marriage, Development, and the Status of Women in Kerala, India".Gender and Development.11(2): 52–59.doi:10.1080/741954317.ISSN1355-2074.JSTOR4030640.S2CID71356583.

- ^abHåberg, Ingunn (2020).Men: a missing factor in SDG 5? A study on gender equality in Kerala with a focus on men's attitudes towards women(MA). Oslo Metropolitan University.

- ^Erwér, Monica (2003).Challenging the genderparadox: women's collective agency in the transformation of Kerala politics.Dept. of Peace and Development Research, Göteborg University.OCLC61115319.

- ^Jeffrey, Robin (2016).Politics, Women and Well-Being: How Kerala Became 'a Model'.Palgrave Macmillan Limited.ISBN978-1-349-12252-3.OCLC1083463758.

- ^abcGrover, Shalini (4 May 2015)."Women, Gender, and Everyday Social Transformation in India".Gender & Development.23(2): 387–390.doi:10.1080/13552074.2015.1053296.ISSN1355-2074.S2CID141504763.

- ^Simister, John (April 2011)."Assessing the 'Kerala Model': Education is Necessary but Not Sufficient".Journal of South Asian Development.6(1): 1–24.doi:10.1177/097317411100600101.ISSN0973-1741.S2CID153551223.

- ^Pradeep Kumar, B (1 December 2020)."Does Gender Status Translate into Economic Participation of Women? Certain Evidence from Kerala".Shanlax International Journal of Economics.9(1): 50–56.doi:10.34293/economics.v9i1.3546.ISSN2582-0192.S2CID229368586.

- ^Ali, Hyfa M.; George, Leyanna S. (30 September 2019)."A qualitative analysis of the impact of Kudumbashree and MGNREGA on the lives of women belonging to a coastal community in Kerala".Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care.8(9): 2832–2836.doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_581_19.ISSN2249-4863.PMC6820395.PMID31681651.

- ^Chathukulam, Jos; Tharamangalam, Joseph (January 2021)."The Kerala model in the time of COVID19: Rethinking state, society and democracy".World Development.137:105207.doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105207.ISSN0305-750X.PMC7510531.PMID32989341.

- ^abcdOomen, T. K. (2009)."Development Policy and the Nature of Society: Understanding the Kerala Model".Economic and Political Weekly.44(13): 25–31.ISSN0012-9976.JSTOR40278657.

- ^abVéron, René (1 April 2001)."The" New "Kerala Model: Lessons for Sustainable Development".World Development.29(4): 601–617.doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00119-4.ISSN0305-750X.

- ^abcOommen, M. A. (2008)."Reforms and the Kerala Model".Economic and Political Weekly.43(2): 22–25.ISSN0012-9976.JSTOR40276897.

- ^abcKurien, John (1995)."The Kerala Model: Its Central Tendency and the Outlier".Social Scientist.23(1/3): 70–90.doi:10.2307/3517892.ISSN0970-0293.JSTOR3517892.

- ^Douthwaite R (1999).The Growth Illusion: How Economic Growth has Enriched the Few, Impoverished the Many, and Endangered the Planet.New Society Publishers. pp. 310–312.ISBN0-86571-396-0.Retrieved11 November2007.

- ^Heinberg R (2004).Powerdown: Options And Actions for a Post-Carbon World.New Society Publishers. p. 105.ISBN0-86571-510-6.Retrieved11 November2007.

- ^ab(McKibben 1999).

- ^Franke, Richard; Chasin, Barbara (August 1999). Parayil, Govindan (ed.)."Is the Kerala Model Sustainable? Lessons from the Past: Prospects for the Future"(PDF).montclair.edu.The Kerala Model of Development: Perspectives on Development and Sustainability: London: Zed Press.Archivedfrom the original on 24 August 1999.Retrieved22 February2022.

- ^Patnaik, Prabhat (1995)."The International Context and the" Kerala Model "".Social Scientist.23(1/3): 37–49.doi:10.2307/3517890.ISSN0970-0293.JSTOR3517890.

- Chandran, VP (2018).Mathrubhumi Yearbook Plus - 2019(Malayalam ed.). Kozhikode: P. V. Chandran, Managing Editor, Mathrubhumi Printing & Publishing Company Limited, Kozhikode.

- McKibben, Bill (October 1999)."Kerala, India".National Geographic Traveler.Archivedfrom the original on 13 April 2002.