2009 Icelandic financial crisis protests

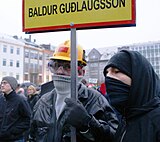

The2009–2011 Icelandic financial crisis protests,also referred to as theKitchenware,Kitchen ImplementorPots and Pans Revolution[1][2](Icelandic:Búsáhaldabyltingin), occurred in the wake of theIcelandic financial crisis.There had been regular and growing protests since October 2008 against theIcelandic government's handling of the financial crisis. The protests intensified on 20 January 2009 with thousands of people protesting at the parliament (Althing) inReykjavík.[3][4][5]These were at the time the largest protests in Icelandic history.[6]

Protesters were calling for the resignation of government officials and for new elections to be held.[7]The protests stopped for the most part with the resignation of the old government led by the right-wingIndependence Party.[8]A new left-wing government was formed after elections in late April 2009. It was supportive of the protestors and initiated a reform process that included the judicial prosecution before theLandsdómurof former Prime MinisterGeir Haarde.

Severalreferendumswere held to ask the citizens about whether to pay theIcesavedebt of their banks. From a complex and unique process, 25 common people, of no political party, were to be elected to form anIcelandic Constitutional Assemblythat would write a newConstitution of Iceland.After some legal problems, a Constitutional Council, which included those people, presented a Constitution Draft to the Iceland Parliament on 29 July 2011.[9]

Chronology

[edit]2008–2009: Protests and government change

[edit]

Concerned with the state of the Icelandic economy,Hörður Torfasonstaged a one-man protest in October 2008. Hörður stood "out on Austurvöllur with an open microphone and invited people to speak".[10]The following Saturday a more organised demonstration occurred, and participants established the Raddir fólksins. The group decided to stage a rally every Saturday until the government stepped down. Hörður led the protest from a stage near the front.[11][12]Speakers, voices of the people (Icelandic: Raddir fólksins) were: Andri Snær Magnason, author; Arndís Björnsdóttir, teacher; Björn Þorsteinsson, philosopher; Dagný Dimmblá, student; Einar Már Guðmundsson, writer; Gerður Kristný, writer; Gerður Pálmadóttir, business woman; Guðmundur Gunnarsson, president ofWriters' Union of Iceland(RSÍ);Halldóra Guðrún Ísleifsdóttir,teacher, artist, and graphic designer; Hörður Torfason, musician and trubator; Illugi Jökulsson, author; Jón Hreiðar Erlendsson; Katrín Oddsdóttir, lawyer; Kristín Helga Gunnarsdóttir, author; Kristín Tómasdóttir, health consultant; Lárus Páll Birgisson, orderly; Lilja Mósesdóttir, economist; Pétur Tyrfingsson, psychologist; Ragnheiður Gestsdóttir, author; Ragnhildur Sigurðardóttir, historian; Sigurbjörg Árnadóttir, journalist; Sindri Viðarsson, historian; Stefán Jónsson, teacher and theatre director; Viðar Þorsteinsson, philosopher; Þorvaldur Gylfason, economist; Þráinn Bertelsson, author. Formal address by Ernesto Ordiss, and Óskar Ástþórsson, kindergarten teacher. Impromptu speakers were Birgir Þórarinsson, Sturla Jónsson, and Kolfinna Baldvinsdóttir.[13]

The protests were a feature of the traditional New Year's Eve comedy revue,Áramótaskaupið,in 2008. The sketches included one ofJón Gnarrplaying a strait-laced middle-aged protester struggling to express his indignation at the crisis and eventually coming up with a sign readingHelvítis fokking fokk!!This phrase soon came to be used in real-life placards and wider discourses surrounding the protests.[14][15][16]

On 20 January 2009, the protests intensified into riots. Between 1,000 and 2,000 people clashed withriot police,who usedpepper sprayandbatons,around the building of the parliament (Althing), with at least 20 people being arrested and 20 more needing medical attention for exposure to pepper spray.[4][17]Demonstratorsbanged potsand honked horns to disrupt the year's first meeting of Prime MinisterGeir Haardeand theAlthing.Some broke windows of the parliament house, threwskyrand snowballs at the building, and threw smoke bombs into its backyard.[3][4][18]Theuse of pots and panssaw the local press refer to the event as the "Kitchenware Revolution".[19]

On 21 January 2009, the protests continued in Reykjavík, where the Prime Minister's car was pelted with snowballs, eggs and cans by demonstrators demanding his resignation.[20][21][22]Government buildings were surrounded by a crowd of at least 3,000 people, pelting them with paint and eggs, and the crowd then moved towards theAlthingwhere one demonstrator climbed the walls and put up a sign that read "Treason due to recklessness is still treason."[20][22]No arrests were reported.

On 22 January 2009, police usedtear gasto disperse people onAusturvöllur(the square in front of theAlthing), the first such use since the1949 anti-NATO protest.[23][24]Around 2,000 protesters had surrounded the building since the day before and they hurled fireworks, shoes, toilet paper, rocks, and paving stones at the building and its police guard. Reykjavík police chiefStefán Eiríkssonsaid that they tried to disperse a "hard core" of a "few hundred" with pepper spray before using the tear gas.[5]Stefán also commented that the protests were expected to continue, and that this represented a new situation for Iceland.[5]

Despite the announcement on 23 January 2009 of early Parliamentary elections (to be held on 25 April 2009) and the announcement of Prime MinisterGeir Haardethat he was withdrawing from politics due toesophageal cancerand would not be a candidate in those elections, protesters continued to fill the streets, calling for a new political scene and for immediate elections;[25]Haarde (Independence Party) announced on 26 January 2009 that he would hand in his resignation as PM shortly, after talks with theSocial Democratic Allianceon keeping the government intact had failed earlier the same day.[26]

The Social Democratic Alliance formed a new government on a minority coalition with theLeft-Green Movement,with the support of theProgressive Partyand theLiberal Party,which was sworn in on 1 February.[27][28]FormerSocial Affairs MinisterJóhanna Sigurðardóttirbecame Prime Minister. The three parties also agree to convene a constitutional assembly to discuss changes to theConstitution.[29]There was no agreement on the question of an early referendum on prospective EU and euro membership.[30]

Theparliamentary electionwas held inIcelandon 25 April 2009[31]followingstrong pressure from the publicas a result of theIcelandic financial crisis.[32]TheSocial Democratic Allianceand theLeft-Green Movement,which formed the outgoingcoalitiongovernment under Prime MinisterJóhanna Sigurðardóttir,both made gains and an overall majority of seats in theAlthing(Iceland's parliament). TheProgressive Partyalso made gains, and the newCitizens' Movement,formed after the January 2009 protests, gained four seats. The big loser was theIndependence Party,which had been in power for 18 years until January 2009: it lost a third of its support and nine seats in the Althing.

2009–2010: Citizen forums and constitutional changing

[edit]Taking its cue from nationwide protests and lobbying efforts by civil organisations, the new governing parties decided that Iceland's citizens should be involved in creating a new constitution and started to debate a bill on 4 November 2009 about that purpose. Parallel to the protests and parliament deliverance, citizens started to unite in grassroots-based think-tanks. A National Forum was organised on 14 November 2009 (Icelandic:Þjóðfundur 2009), in the form of an assembly ofIcelandiccitizens at theLaugardalshöllinReykjavík,by a group ofgrassrootscitizen movements such as Anthill. The Forum would settle the ground for the2011 Constitutional Assemblyand was streamed via the Internet to the public.

Fifteen hundred people were invited to participate in the assembly; of these, 1,200 were chosen at random from the national registry, while 300 were representatives of companies, institutions and other groups. Participants represented a cross section of Icelandic society, ranging in age from 18 to 88 and spanning all sixconstituencies of Iceland,with 73, 77, 89, 365 and 621 people attending from theNorthwest,Northeast,South,SouthwestandReykjavík(combined), respectively; 47% of the attendants were women, while 53% were men.

On 16 June 2010 the Constitutional Act was accepted by parliament and a new Forum was summoned.[33][34]The Constitutional Act prescribed that the participants of the Forum had to be randomly sampled from the National Population Register, "with due regard to a reasonable distribution of participants across the country and an equal division between genders, to the extent possible".[35]The National Forum 2010 was initiated by the government on 6 November 2010 and had 950 random participants, organized in subcommisions, which would present a 700-page document that would be the basis for constitutional changes, which would debate a future Constitutional Assembly. The Forum 2010 came into being due to the efforts of both governing parties and the Anthill group. A seven-headed Constitutional Committee, appointed by the parliament, was charged with the supervision of the forum and the presentation of its results, while the organization and facilitation of the National Forum 2010 was done by the Anthill group that had organized the first Forum 2009.

2010–2011: Constitutional Assembly and Council

[edit]The process continued in theelection of 25 peopleof no political affiliation on 27 November 2010. TheSupreme Court of Icelandlater invalidated the results of the election on 25 January 2011 following complaints about several faults in how the election was conducted,[36][37]but the Parliament decided that it was the way, and not the elects, that had been questioned, and also that those 25 elects would be a part of a Constitutional Council and thus the Constitutional change went on.[38]On 29 July 2011 the draft was presented to the Parliament.[9]

2012: Referendum on the new constitution

[edit]After the draft of the Constitution was presented on 29 July 2011, the Alþingi, the Icelandic parliament, finally agreed in a vote on 24 May 2012, with 35 in favor and 15 against, to organize an advisory referendum on the Constitutional Council's proposal for a new constitution no later than 20 October 2012. The only opposing parliament members were the former governing right party, the Independence Party. Also a proposed referendum on discontinuingthe accession talks with the European Unionby some parliamentaries of the governing left coalition was rejected, with 34 votes against and 25 in favour.[39]

-

18 October 2008

-

8 November 2008

-

15 November 2008

-

22 November 2008

-

1 December 2008

-

13 December 2008

-

20 December 2008

-

31 December 2008

-

3 January 2009

-

8 January 2009

-

10 January 2009

-

17 January 2009

-

20 January 2009

-

20 January 2009

-

21 January 2009

-

21 January 2009

-

24 January 2009

-

24 January 2009

-

26 January 2009

-

31 January 2009

Banking debt referendums

[edit]There were several referendums to decide about theIcesaveIcelandic bank debts. The firstIcesave referendum(Icelandic:Þjóðaratkvæðagreiðsla um Icesave), was held on 6 March 2010.[40]The referendum was resoundingly defeated, with 93% voting against and less than 2% in favor.

After the referendum, new negotiations commenced. On 16 February 2011 the Icelandic parliament agreed to a repayment deal to pay back the full amount starting in 2016, finalising before 2046, with a fixed interest rate of 3%.[41]The Icelandic president once again refused to sign the new deal on 20 February, calling for a new referendum.[42][43]Thus, asecond referendumwas held on 9 April 2011 also resulting in "no" victory with a lesser percentage.[44]After the referendum failed to pass, the British and Dutch governments said that they would take the case to theEuropean courts.[45]

PM trial

[edit]The Althing (Iceland's parliament) voted 33–30 to indict the former Prime MinisterGeir Haarde,but not the other ministers, on charges of negligence in office at a session on 28 September 2010.[46]He would stand trial before theLandsdómur,a special court to hear cases alleging misconduct in government office: it will be the first time theLandsdómurhas convened since it was established in the 1905Constitution.[47]

The trial began in Reykjavík on 5 March 2012.[48]Geir Haarde was found guilty on one of four charges on 23 April 2012, for not holding cabinet meetings on important state matters.[49]Landsdómur said Haarde would face no punishment, as this was a minor offence and the Icelandic State was ordered to pay all his legal expenses.[50]Haarde decided, as a matter of principle, to refer the whole case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg where it was eventually dismissed.[51]

Commentary

[edit]Roger BoyesofThe Timesargued the protests were part of a "new age of rebellion and riot" in Europe, in the background of similar protests caused by the financial crisis inLatvia,Bulgariaand thecivil unrest in Greece,triggered by the police killing a teenager, but with deeper roots related to the financial crisis.[52]

London School of Economicsprofessor Robert Wade said that Iceland's government would fall within the coming days andFredrik Erixonof the Brussels-basedEuropean Centre for International Political Economycompared the current situation with theFrench Revolution of 1789.[53]

Eirikur Bergmann, an Icelandic political scientist, wrote inThe Guardianthat "While Barack Obama was beingsworn into officeonCapitol Hillyesterday, the people of Iceland were starting the first revolution in the history of the republic. The word "revolution" might sound a bit of an overstatement, but given the calm temperament that usually prevails in Icelandic politics, the unfolding events represent, at the very least, a revolution in political activism. "[54]Valur Gunnarsson, also ofThe Guardian,writes that "Iceland's government was last night scrambling to avoid becoming the first administration to be ousted by the global financial crisis." He also writes that "The protesters have begun referring to their daily attempt to oust the government as a 'saucepan revolution', because of the noise-inducing pots and pans brought along to the protests."[55]

Eva Heiða Önnudóttir studied the demography of the protesters to see whether participants in the Austurvöllur protests came from groups with greater histories of political participation and greater access to political resources than non-participants, but found that this was not a determining factor: rather, participants were simply more likely to have a direct personal incentive to protest.[56]

Writing in the wake of the2013 Icelandic parliamentary election,which returned to power the parties most closely associated with Iceland's banking boom,Gísli Pálssonand E. Paul Durrenberger concluded that

While the grassroots movement that overthrew the government after the crash remains disillusioned and disappointed, its impact should not be under-estimated. One important development in its wake, and an important emerging theme for further research, is a series of experiments with direct democracy and social media. Soon after the crash, a crowd-sourcing company drew upon social media to prepare for a National Meeting (Þjóðfundur) of 1,000 participants for outlining a new constitution. While the end result of this work remains unclear, and much depends on the formal, indirect democracy of the Parliament, it seems safe to say that the public has been sensitized to new avenues for democracy and alerted to potential signs of corruption.[57]

See also

[edit]- 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis

- 2009 Iranian presidential election protests

- 2010–2011 Greek protests

- 15 October 2011 global protests

- 2011 Chilean protests

- 2011 Israeli social justice protests

- Spanish 15M Indignants movement

- 2011 United Kingdom anti-austerity protests

- 2012 Quebec student protests

- Arab Spring

- Impact of the Arab Spring

- "Occupy" protests

- Occupy Wall Street

- Protests of 1968

References

[edit]- ^Leigh Phillips (27 April 2009)."Iceland Turns Left and Edges Toward EU".Bloomberg Business Week.Archived fromthe originalon 23 July 2013.Retrieved20 October2011.

- ^Magnússon, Sigurdur:Wasteland With Words,2010. Reaktion Books, London. p. 265.

- ^abGunnarsson, Valur (21 January 2009)."Icelandic lawmakers return to work amid protests".Associated Press. Archived fromthe originalon 31 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^abc"Iceland protesters demand government step down".Reuters.20 January 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 3 February 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^abcGunnarsson, Valur; Lawless, Jill (22 January 2009)."Icelandic police tear gas protesters".Associated Press. Archived fromthe originalon 31 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^Önnudóttir, Eva H. (19 December 2016)."The" Pots and Pans "protests and requirements for responsiveness of the authorities".Icelandic Review of Politics & Administration.12(2): 195–214.doi:10.13177/irpa.a.2016.12.2.1(inactive 18 April 2024).hdl:20.500.11815/230.ISSN1670-679X.

{{cite journal}}:CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - ^"Opposition attempts to call Iceland elections, bypassing PM".icenews.is. 22 January 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^Nyberg, Per (26 January 2009)."Icelandic government falls; asked to stay on".CNN.Archivedfrom the original on 29 January 2009.Retrieved31 January2009.

- ^ab"Stjórnlagaráð 2011 – English".Stjornlagarad.is. 29 July 2011.Retrieved18 October2011.

- ^Alda (4 February 2009)."We need far more radical changes".Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2020.Retrieved28 November2022.31 March 2009.

- ^Henley, John (1 December 2008)."Iceland has an unlikely new hero".The Guardian.UK. Archived fromthe originalon 3 February 2009.Retrieved31 March2009.31 March 2009.

- ^"Icelanders demand PM resignation, clash with police".Thomson Financial News. 22 November 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 31 March 2009.Retrieved31 March2009.31 March 2009.

- ^"Raddir Fólksins » Ávörp og ræður".raddirfolksins.info.Retrieved7 October2018.

- ^Jón Gnarr – Helvítis Fokking Fokk!.1 January 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^"Helvítis fokking fokk á forsíðu Hrunsins".visir.is.5 June 2009.

- ^Sellgren, Auður Inez (December 2014).Lokaverkefni: "Ekta upplifun?: Orðin ekta og gervi skoðuð með tilliti til mannsins" eftir Auður Inez Sellgren 1990 [2014] – Skemman(Thesis).hdl:1946/22190.

- ^"Iceland's capital rocked by protests".Radio Netherlands Worldwide.20 January 2009. Archived fromthe originalon 23 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^"Icelanders held over angry demo".BBC. 21 January 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^Ian Parker, Letter from Reykjavík, "Lost,"The New Yorker,9 March 2009, p. 39.

- ^abWaterfield, Bruno (21 January 2009)."Protesters pelt car of Icelandic prime minister".The Telegraph.UK.Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^"Protesters pelt Iceland PM's car".BBC. 21 January 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^abValdimarsson, Omar R.; Lannin, Patrick; Klesty, Victoria; Moskwa, Wojciech; Pollard, Niklas; Jones, Matthew (21 January 2009)."Iceland protests grow, premier vows to stay on".Reuters.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^"Táragasi beitt á Austurvelli"(in Icelandic). mbl.is. 22 January 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^Gunnarsson, Valur; Lawless, Jill (22 January 2009)."UN: Myanmar, China pushed high 2008 disaster toll".Associated Press. Archived fromthe originalon 31 January 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^McLaughlin, Kim (24 January 2009)."Protesters demand Iceland government quits now".International Herald Tribune.Archivedfrom the original on 2 February 2009.Retrieved31 January2009.

- ^Einarsdottir, Helga Kristin (26 January 2009)."Iceland's Ruling Coalition Splits Following Protests".Bloomberg.Retrieved31 January2009.

- ^New Iceland government under negotiation,IceNews, 27 January 2009, archived fromthe originalon 27 October 2012,retrieved17 October2011

- ^No new Icelandic government this weekend,IceNews, 31 January 2009, archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2012,retrieved17 October2011

- ^"Iceland to Convene Constitutional Parliament",Iceland Review,30 January 2009, archived fromthe originalon 23 February 2009,retrieved17 October2011

- ^"Iceland's Social Democrats Want a Vote on EU in May",Iceland Review,27 January 2009, archived fromthe originalon 17 February 2012,retrieved17 October2011

- ^Kosningar 9. maí og Geir hættir,RÚV,23 January 2009, archived fromthe originalon 9 August 2011,retrieved17 October2011.(in Icelandic)

- ^"Iceland announces early election",BBC News,23 January 2009,retrieved17 October2011

- ^"Act on a Constitutional Assembly"(PDF).16 June 2010.Archived(PDF)from the original on 28 May 2022.

- ^"Þjóðfundur 2010 – Fréttir – The main conclusions from the National Forum 2010".Thjodfundur2010.is.Retrieved18 October2011.

- ^Act on a Constitutional Assembly, Interim Provision

- ^"Kosning til stjórnlagaþings ógild".mbl.is.

- ^"Hæstiréttur Íslands".haestirettur.is.Archived fromthe originalon 22 January 2016.

- ^"Constitutional Assembly Elects Appointed to Council – Iceland Review O".Icelandreview.com. Archived fromthe originalon 28 February 2011.Retrieved18 October2011.

- ^"Referendum to Be Held on Icelandic Constitution".Iceland Review.Archived fromthe originalon 18 June 2012.Retrieved5 June2012.

- ^"Icesave referendum set for 6 March".BBC News.19 January 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 21 January 2010.Retrieved19 January2010.

- ^IJslandse parlement stemt in met Icesave-dealnu.nl, 16 February 2011

- ^Iceland president triggers referendum on Icesave repaymentsby Julia Kollewe,The Guardian20 February 2011

- ^President IJsland tekent Icesave-akkoord nietnu.nl, 20 February 2011

- ^"Iceland to hold April referendum on overseas bank compensation plan".Monsters and Critics. 25 February 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 27 February 2011.Retrieved12 April2011.

- ^"Iceland government says not threatened by referendum defeat".MSN. 11 April 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 4 April 2020.Retrieved11 April2011.

- ^"Iceland's Former PM Taken to Court".Iceland Review Online.28 September 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 25 March 2011.Retrieved28 September2010.

- ^"Islands tidligere statsminister stilles for riksrett".Aftenposten(in Norwegian). Oslo, Norway.NTB.28 September 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 1 October 2010.Retrieved28 September2010.

- ^Trial of Iceland ex-PM Haarde over 2008 crisis begins,BBC News, 5 March 2012

- ^National Public Radio[permanent dead link]23 April 2012 (Broken link)

- ^Iceland ex-PM Haarde 'partly' guilty over 2008 crisis,BBC News, 23 April 2012

- ^"HUDOC – European Court of Human Rights".

- ^Boyes, Roger (22 January 2009)."New age of rebellion and riot stalks Europe".The Times.London.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2009.Retrieved22 January2009.

- ^O'neil, Peter (23 January 2009)."European leaders fear civil unrest over economic woes".Ottawa Citizen.Archived fromthe originalon 31 January 2009.Retrieved31 January2009.

- ^Bergmann, Eirikur (21 January 2009)."The heat is on – Iceland's government is on the point of collapse as angry protesters stake out the parliament in Reykjavík".The Guardian.UK.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2009.Retrieved31 January2009.

- ^Gunnarsson, Valur (22 January 2009)."Iceland's coalition struggles to survive protests".The Guardian.UK.Archivedfrom the original on 25 January 2009.Retrieved31 January2009.

- ^Eva Heiða Önnudóttir (2011)."Búsáhaldabyltingin: Pólitískt jafnræði og þátttaka almennings í mótmælum – Rannsóknir í félagsvindum: Stjórnmálafræðideild,12 "(PDF).pp. 36–44. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 March 2016.Retrieved3 September2015.

- ^Gísli Pálsson and E. Paul Durrenberger, "Introduction: The Banality of Financial Evil", inGambling Debt: Iceland's Rise and Fall in the Global Economy,ed. by E. Paul Durrenberger and Gisli Palsson (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2015), pp. xiii—xxix (p. xxvii).