Kobold

Akobold(kobolt,kobolde,kobolde,[2]cobold) is a general or generic name for thehousehold spiritinGerman folklore.Ahausgeist.

It may invisibly make noises (i.e., be apoltergeist), or helpfully perform kitchen chores or stable work. But it can be a prankster as well. It may expect a bribe or offering of milk, etc. for its efforts or good behaviour. When mistreated (cf. fig. right), its reprisal can be utterly cruel.[a]

Ahütchen(Low German:hodeken) meaning "little hat" is one subtype; this and other kobold sprites are known for its pointy red cap, such as theniss(cognate ofnisseof Norway) orpuk(cognate ofpuckfairy) which are attested in Northern Germany, alongsidedrak,a dragon-type name, as the sprite is sometimes said to appear as a shaft of fire, with what looks like a head. There is also the combined formNis Puk.

A house spriteHinzelmannis a shape-shifter assuming many forms, such as a feather or animals. The name supposedly refers to it appearing in cat-form, Hinz[e] being an archetypical cat name. The similarly namedHeinzelmänchenof Cologne (recorded 1826) is distinguished from Hinzelmann.[7]

TheSchratis cross-categorized as a wood sprite and a house sprite, and some regional examples correspond to kobold, e.g.,Upper Franconiain northern Bavaria.[8][10]The kobold is sometimes conflated with the mine demonkobelorBergmännlein/Bergmännchen,whichParacelsusequated with the earth elementalgnome.It is generally noted that there can be made no clear demarcation between a kobold and nature spirits.[11]

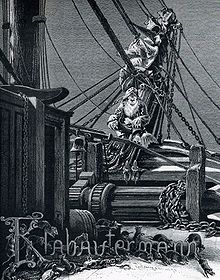

TheKlabautermannaboard ships are sometimes classed as a kobold.

Overview

[edit]A kobold is known by various names (discussed under§ Subtypes). As a household spirit, it may perform chores such as tidying the kitchen, but can be prankish, and when mistreated can resort to retribution, sometimes of the utmost cruelty. It is often said to require the household to put out sweet milk (and bread, bread soup) as offering to keep it in good behaviour.

The legend of the house sprite's retribution is quite old. The tale of thehütchen(orhodekinin Low German, meaning "little hat"; tale retold as GrimmsDeutsche SagenNo. 74) is set in the historical background after c. 1130, and attested in a work c. 1500.[b]This sprite that haunted the castle of the Bishop ofHildesheim,[c]retaliated against a kitchen boy who splashed filthy water on it (Cf. fig. top right) by leaving the lad'sdismemberedbody cooking in a pot. Likewise the residentChimmekenof Mecklenburg Castle, in 1327, allegedly chopped up a kitchen boy into pieces after he took and drank the milk offered to the sprite, according to an anecdote recorded by historianThomas Kantzow(d. 1542).

The story of the "multi-formed"Hinzelmann(GrimmsDSNo. 75)[12]features a typical house sprite, tidying the kitchen, repaying insolence, etc. Though normally invisible, it is ashapeshifteras its byname suggests. When the lord ofHudemühlen Castleflees toHanover,the sprite transforms into a feather to follow the horse carriage. It also appears as a marten and serpent after attempts at expelling it.

A kobold by the similar name Heinzchen was recorded byMartin Luther.Although a group of house sprite names (Heinz, Heinzel, Heinzchen, Heinzelman, Hinzelman, Hinzemännchen, etc.) are considered to derive fromdiminutive pet nameof "Heinrich", the name Hinzelmann goes deeper, and alludes to the spirit appearing in the guise of a cat, the name Hinz[e] being an archetypical name for cats. Also Hinzelmann andHeinzelmänchenof Cologne are considered different house sprites altogether, the latter categorized as one of "literary" nature.[7]The house sprite names Chim or Chimken, Chimmeken, etc. are diminutive informal names of Joachim.

But its true form is often said to be that of a small child, sometimes only felt to be as such by the touch of the hand, but sometimes a female servant eager to see it is shown a dead body of a child (cf. Hinzelmann). The folklore was current in some regions, e.g. Vogtland that the kobold was the soul of a child who died unbaptized. The Grimms (Deutsche Sagen) also seconded the notion of "kobold" appearing as a child wearing a pretty jacket, butJacob Grimm(Deutsche Mythologie) stated contrarily that kobolds are red-haired and red-bearded, without examples. Later commentators noted that the house spritePetermännchensports a long, white beard. TheKlabautermannis red-haired and white-bearded according to a published source.[d]

The kobold often has the tendency to wear red pointy hats, a widely disseminated mark of European household spirits under other names such as the Norwegiannisse;the North or Northeastern German kobolds named Niss or Puk (cog.puck) are prone to wearing such caps. The combined formNis Pukis also known. In the north the house sprite may be known by the dragon-like namedrak,said to appear in a form like a fire shaft.

Sometimes household sprites manifests as a noisemaker (poltergeist). It may first be such a rattler, then an invisible speaker, then a sprite doing chores, etc. and gradually making its presence and personality more clear (seeHintzelmanntale). In some regions, the kobold is held to be the soul of a prematurely killed child (§ True identity as child's ghost).

They may be hard to eradicate, but it is often said that a gift of an article of clothing will cause them to leave.[e][14][17]

Theklopferis a "noisemaker" orpoltergeisttype of kobold name, while thepoppeleandbutz(which Grimm and others considered to be noise inspired) are classed as names referring to a doll or figurine.[4]

The namekobolditself might be classed in this "doll" type group, as the earliest instances of use of the wordkoboldin 13th centuryMiddle High Germanrefers jokingly to figurines made of wood or wax,[18][19]and the word assumptively also meant "household spirit" in MHG,[21]and certainly something of a "household deity" in the post-medieval period (gloss dated 1517).[23]

The etymology ofkoboldthat Grimm supported derived the word from Latincobalus(Greekκόβαλος,kobalos),[24]but this was alsoGeorg Agricola's Latin/Greek cypher forkobel,syn.Bergmännleindenoting mine spirits, i.e.gnome.[28]This Greek etymology has been superseded by the Germanic one explaining the word as the compoundkob/kof'house, chamber' +walt'power, authority' (cf.cobalt#etymology).

Thegütelhas a variantheugütel,ahayloftor stable kobold, which tampers with horses.

Nomenclature and origins

[edit]The "kobold" is defined as the well-knownhousehold spirit,descended from household gods and hearth deities, according to Grimms' dictionary.[30]

However,Middle High German"kóbolt, kobólt"is defined as" wooden or waxen figures of a fairyish (neckische) house spirit ", used in jest.[31]

Kobold as generic term

[edit]

The term "kobold" was being used as general or generic term for "house spirit" known by other names even before Grimm, e.g.,Erasmus Francisci(1690) who discusses thehütchentale under the section on "Kobold".[32][f]The bookHintzelmann(published 1701, second edition 1704) published by an anonymous author based on the diaries of Pastor Feldmann (fl. 1584–1589)[33]also used "kobold" and "poltergeist" in commentary,[34]but this cannot be considered an independent source since the book cites Erasmus Francisci elsewhere.[35][g]Both these were primary sources for the kobold tales in Grimms'Deutsche Sagen,No. 74, 75.

Praetorius (1666) discussed the household spirit under names such asHausmann(dat. pl.haußmännern[sic], kobold, gütgen, and Latin equivalents.[36]

Steier (1705) glossing kobold as "Spiritus familiaris"[37]perhaps indicates kobold being considered a generic term.

Glossed sources

[edit]It is a relatively latevocabulariuswherekobelteis glossed as (i.e., analogized as) the Roman house and hearth deities "Lares"andPenates,as in Trochus (1517),[23]or "kobold" with "Spiritus familiaris"as in Steier (1705).[37]

While the term "kobold" is attested inMiddle High Germanglossaries,[31]they may not corroborate a "house spirit" meaning. The termskobulttogether withbancstichil, alp, moreto glossprocubusinDiefenbach's[38]source (Breslauer'sVocabularius,1340[39])[40]may (?) suggest "kobold" being regarded more like analpandmarewhich are dream demons.

But indications are that these Germanic household deities were current in the older periods, attested by Anglo-Saxoncofgodu(glossed "penates" )[18][20]and Old High German (Old Frankish)Old High German:hûsing, herdgotafor house or hearth deities also glossed aspenates.[43]

- (Middle High German location spiritstetewalden)

There is an attestation to akobold-like name for a house or location spirit, given asstetewalden[44]by Frater Rudolfus of the 13th century,[45]meaning "ruler of the site" (genius loci).[6][46]

Ur-origins

[edit]Otto Schraderalso observed that "cult of the hearth-fire" developed into "tutelary house deities, localized in the home", and the German kobold and the Greekagathós daímōnboth fit this evolutionary path.[49][52]

Etymology

[edit]Thekobaltetymology as consisting ofkob"chamber" +walt"ruler, power, authority", with the meaning of "household spirit"has been advanced by various authors, as early asChristian W. M. Grein(1861–1864) who postulated a form*kobwalt,and quoted in Grimms' dictionary.[20]Other writers such as Müller-Fraureuth (1906) also weighed in on the question of its etymology.[53][55]

Other linguists such asOtto Schrader(1908) suggested ancestral (Old High German)*kuba-walda"the one who rules the house".[47]Dowden (2002) offers the hypothetical precursor*kofewalt.[51]

Thekob/kub/kuf-root is possibly related toOld Norse/Icelandic:kofe"chamber",[53][56]orOld High German:chubisi"house".[56]and the English word "cove" in the sense of 'shelter'.[53][h][i]

This is now accepted as the standard etymology.[58][11]Even though the Grimm were aware of it,[59]Jacob Grimm seemingly endorsed a different etymology (§ Grimm's alternate etymology), though this eventually got displaced.[54][60]

Kobold as doll

[edit]There are no attested uses of the word "kobold" (Middle High German:kobolt) prior to the 13th century. Grimm opines that earlier uses may have existed, but remain undiscovered or lost.[61][j]

The earliest known uses of the wordkoboldin 13th centuryMiddle High Germanrefer jokingly to figurines made of wood or wax.[18][19]The exemplum inKonrad von Würzburg's poem (<1250) refers to a man as worthless as a kobold-doll made fromboxwood.[62][k]

This use does not directly support the notion of the kobold being regarded as a spirit or deity. The scenario conjectured by Grimm (seconded byKarl Simrockin 1855) was that home sprites used to be carved from wood or wax and set up in the house, as objects of earnest veneration, but as the age progressed, they degraded into humorous or entertaining pieces of décor.[64][66]

- (Stringed puppet)

ThekoboltandTatrmannwere also boxwood puppets manipulated by wires, which performed in puppet theater in the medieval period, as evident from example usage.[67][68]The travelingjuggler(‹See Tfd›German:Gaukler) of yore used to make a kobold doll appear out of their coats, and make faces with it to entertain the crowd.[69][67]

Thomas Keightleycomments that legends and folklore about kobolds can be explained as "ventriloquism and the contrivances of servants and others".[70]

The 17th century expressionto laugh like a koboldmay refer to these dolls with their mouths wide open, and it may mean "to laugh loud and heartily".[71]

- (Dumb doll insult)

There are other medieval literary examples usingkoboldortatrmannas a metaphor for mute or dumb human beings.[72]

Note that some of the kobold synonyms are specifically classified asKretinnamen,under the slander for stupidity category in theHdA,as aforementioned.[73]

Grimm's alternate etymology

[edit]Joseph Grimm inTeutonic Mythologygave the etymology ofkobold/koboltas derived from Latincobalus(pl.cobali) or rather its antecedent Greekkoba'los(pl.kobaloi;Ancient Greek:Κόβαλος,plural:Κόβαλοι) meaning "joker, trickster".[l][79][m]The final-olthe explained as typicalGerman languagesuffix for monsters and supernaturals.[80]

The derivation ofkoboldfrom Greekkobalosis not original to Grimm, and he creditsLudwig Wachler(1737).[82][83]

Thus the generic "goblin"[42]is a cognate of "kobold" according to Grimm's etymology, and perhaps even a descendant word deriving from "kobold".[51][84]TheDutchkabout,kabot,kabouter,kaboutermanneken,etc., were also regarded as deriving fromcabolusby Grimm, citing Dutch linguistCornelis Kiliaan.[85][24]

Conflation with mine spirit

[edit]Jacob Grimm certainly knew thatkobelandBergmännlein(=Bergmännchen[n]) were the proper terms Agricola used for "mine spirits" since hisDeutsche Mythologiequoted these terms fromGeorgius Agricola(16th cent.) in the annotation volume.[86][o]

But Grimms' dictionary, while admitting that the mine spirit went by the namekobel,considered that word merely to be a variant or offshoot ofkobold(for the house spirit). The dictionary stated under "kobold" thatkobelmust be a diminutive cognateNebenform).[88]And under "kobalt" it considered the name ofcobaltore derived from the supposed mischief caused by thekoboldorBergmännchen(mountain manikin, mountain spirit) in these mines.[89]

Thus unsurprisingly, later writers have continued referring to mine spirits as "kobolds", or to consider "kobold" to be both house spirit and mine spirit in a wider sense[92](cf.§ Literary references,§ Fantasy novels and anime). The conflation between kobold "house spirit" andkobel"mine spirit", German linguistPaul Kretschmer(1928) recapped the later "standard" etymology ofkoboldderived fromkoben"chamber' +walt"ruler, power, authority", and observed that this original sense of "house spirit" (Hausgeist) underwent a meaning-shift or conflation with "mine spirits".

Visitors from mines

[edit]SpiritualistEmma Hardinge Britten(1884) recorded a story about a "kobolds" in the mines who communicated with local German residents (ofHarz Mountains?) using banging sounds, and fulfilled the promise to visit their homes. Extracted as real-life experience from a Mrs. Kalodzky, who was visiting peasants named Dorothea and Michael Engelbrecht.[93]As promised, these kobolds appeared in the house in shadow as small human-like figures "more like a little image carved out of black shining wood".[94][p]The informant claims she and her husband[q]have both seen the beings since, and described them as "diminutive black dwarfs about two or three feet in height, and at that part which in the human being is occupied by the heart, they carry the round luminous circle", and the sighting of the circle is more common than the dwarfish beings.[91]

Subtypes

[edit]- (Other house spirits)

A.![]() [Doll] Güttel,[97]Poppele[100].

[Doll] Güttel,[97]Poppele[100].

B.![]() [Cretin] Schretzelein[103]

[Cretin] Schretzelein[103]

C.![]() a) [Apparel] Hüdeken[104]b) [Beastform] Hinzelmann,[106]Kazten-veit[107]

a) [Apparel] Hüdeken[104]b) [Beastform] Hinzelmann,[106]Kazten-veit[107]

D.![]() [Noise] Klopfer[109]

[Noise] Klopfer[109]

E.![]() [Person name] Chimmeken[111]Woltken, Chimken[113]Niß-Puk[115][s]

[Person name] Chimmeken[111]Woltken, Chimken[113]Niß-Puk[115][s]

G.![]() [Demon] Puk[117]

[Demon] Puk[117]

H.![]() [Literary] Heinzelmänchen[118]

[Literary] Heinzelmänchen[118]

I.![]() [Dragon] Drak.[122]Alrun[124][126]

[Dragon] Drak.[122]Alrun[124][126]

The termkoboldhas slipped into becoming a generic term, translatable asgoblin,so that all manners of household spirits (hausgeister) became classifiable as "types" of kobold. Such alternate names for thekoboldhouse sprite are classified by type of naming (A. As doll, B. As pejoratives for stupidity, C. Appearance-based, D. Characteristics-based, E. Diminutivepet namebased), etc., in theHandwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens(HdA).[t][4]

A geographical map of Germany labeled with the different regional appellations has appeared in a 2020 publication.[6]

Grimm, after stating that the list of kobold (or household spirit) in German lore can be long, also adds the namesHütchenandHeinzelmann.[127]

Doll or puppet names

[edit]The termkoboldin its earliest usage suggest it to be a wooden doll (Cf. §Origins under§ Doll or idolbelow). A synonym for kobold in that sense includesTatrmann,which is also attested in the medieval period.[62]

What is clear is that these kobold dolls were puppets used in plays and by travelling showmen, based on 13th century writings. They were also known astatrmannand described as manipulated by wires. Either way, the idol or puppet was invoked rhetorically in writing by theminstrels,etc. to mockclergymenor other people.[128]

The household spirit namespoppeleandbutzwere thought by Grimm to derive from noise-making,[129]but theHdAconsiders them to be doll names. Thepoppeleis thought to be the German wordPuppefor doll.[130]The termButzmeanwhile could refer to a "tree trunk", and by extension either "overgrown" or "little", or "stupid" thus is cross-categorized as an example of "cretin names" (category B).[4][131]Ranke suggests the meaning ofKlotz( "klutz, hunk of wood" ) or a "small being", with a "noisemaker ghost" is possible by descent from MHGbôzen"to beat, strike".[132]

While the MHG dictionary definesButzeas a "knocking[-sound making] kobold" or poltergeist, or frightening form,[133]Grimm thinks that all MHG usage treatsbutzeas a type of bogey orscarecrow(Popanz und Vogelscheuch).[134]So in some sense,Butz[e] is simply a generic bogeyman (German:Butzemann). Andbutz[e], while nominally a kobold (house spirit), is almost a generic term for all kinds of spectres in the Alps region.[132]

TheEast Central Germannamegütelorgüttel(diminutive of "god", i.e. "little god", var.heugütel[96][15]) has been suggested as a kobold synonym of the fetish figurine type.[135]Grimm knew the term but placed the discussion of it under the "Wild man of the woods"section[136]conjecturing the use ofgüttelas synonymous togötze(i.e., sense of 'idol') in medievalheroic legend.[137][138]The termgütelanswers to Agricola'sguteli(in Latin) as an alternate common name for the mine spirit (bergmännlein).[26][95]

Mandrake root dolls

[edit]

TheHdAcategorizesAlruneas a dragon name.[139]In English, "mandrake" is easily seen as a "-drake" or "dragon" name. In German, a reference needs be made to the Latin formmandragorawhere-dragoracame to be regarded as meaning a dragon.[140]

Since the mandrake do not natively grown in Germany, the so-calledAlrunedolls were manufactured out of the available roots such asbryonyof the gourd family,gentian,andtormentil(Blutwurz).[140]: 316 The lore surrounding them is thus more like a charm whose possession brought luck and fortune, supposedly through the agency of some spirit,[140]: 319 rather than a house-haunting kobold. The alraune doll was also known by names such asglücksmännchen(generic name for such dolls[141]) andgalgenmännlein.[141][140]It is a mistake to consider such alraun dolls as completely equivalent to the kobald, the household spirit, in Grimm's opinion.[143]

But the kobold kind known as Alrune (alrûne) did indeed exist locally in the folklore of the north, inSaterland,Lower Saxony.[144][145]Alrune was also recognized as a kobold-name in Friesland.[145][u][v]

Cretin names

[edit]The aforementionedbutzmay allude to a wooden object, or a "dolt" by extension. TheSchrat(Schratte) is also formally categorized as a "cretin name" type of kobold nomenclature in theHdA.[4]However, the termSchratand its variants has remained current in the sense of "house spirit" only in certain parts such as "southeast Germany": more specifically northern Bavaria including theUpper Palatinate,Fichtel Mountains,Vogtland(into Thuringia), and Austria (StyriaandCarinthia) according to the various sources theHdAcites.[148]

The tale "Schrätel und wasserbär" (kobold and polar bear) had been recorded inMiddle High German,[149]and is recognized as a "genuine" kobold tale.[9]The tale is set in Denmark, whose king received the gift of a polar bear and lodges at a peasant's house infested by a "schretel". But the it is driven away by the ferocious bear, which the spirit thinks is a "big cat".[149]Obviously Scandinavian origin is suspected, with the Norwegian version retaining the polar bear which turns into other beasts in Central European variants.[150]Old Norse/Icelandicskrattimeaning "sorcerer, giant" has been listed as cognate forms.[151]

There exists a version of this water-bear tale, set inBad Berneck im Fichtelgebirge,Upper Franconia,where aholzfräuleinhas been substituted for the schrätel, and the haunting occurring at a miller's, and the "big cat" dispatching the spirit.[152]Still, the formsschrezalaandschretseleinseemed to be current around Fichtelgebirge (Fichtel Mountains), or at least in Upper Franconia region as a sprit haunting a house or stable.[154]Theschrezalaform is recognized in Vogtland also.[13]

Thusschretzeleinis marked in Upper Franconia (aroundHof, Bavaria) in the location map above, based on additional sources.[155][156]Aschretzchenreputedly haunted a household atKremnitzmühlenearTeuschnitz,Upper Franconia, and tended to cattle, washed the dishes, and put out the fire. But when the mistress of the house well-intendedly gave the gift of clothing to the spirit who looked like a six-year oldragamuffin,it exclaimed it had been now been given payment and must now leave.[13][e]However, the formsschrägele, schragerlnare marked in Upper Franconia andschretzeleininLower Franconiaon Schäfer et al.'s map.[6]

Forms ofschratas kobold also occurs in Poland asskrzat,glossed in a c. 1500 dictionary as a household spirit (duchy rodowe), also known by variantskrot.[158]The Czech forms (standardized asškrat, škrátek, škrítek) could mean a kobold, but could also denote a "mine spirit" or ahag.[160]

Pet names

[edit]There is a roster of names of kobolts or little folk derived from shortened affectionate forms of human names, including Chimken (Joachim), Wolterken (Walter), Niss (Nils).[161][162]

While Heinz is categorized as C subtype "beast-shape name" in the HdA (Cf.§ Cat-shape,below), and the form Heinzchen mentioned by Martin Luther[163][164]is unacknowledged, these are also explained as Heinz group of names, i.e., affectionate shortened forms of Heinrich, as commentated on by Grimm under such kobold names as Heinze (alsoheinzelman, hinzelman, hinzemännchen).[165]

The koboldHeinzelmännchen(another diminutive of Heinrich[161]) is particularly associated with Cologne,[3]is actually separated out as a "Category H Literary name" in the HdA,[166]apparently regarded as a late literary invention or reconstruction.[169]The Heinzelmännchen is also clearly distinguished from the Hinzelmann in current scholarship, according to modern linguistElmar Seebold,[3]though they may have beeninterchangeably discussed in the past. Accordingly, a mix of heinzelman, hinzelman "were given as" pet name (shortened human name) "type of kobold names by Grimm,[165](cf.§ Heinzelmännchenbelow and the daughter articleHeinzelmännchen).

Chimke (var. Chimken, Chimmeken), diminutive ofJoachimis aNiederdeutschfor apoltergeist;the story of "Chimmeken" dates to c. 1327 and recorded inThomas Kantzow's Pomeranian chronicle (cf.§ Offerings and retributions).[110][170]Chimgen (Kurd Chimgen[173]), and Chim are other forms.[174][175][176][178]

Wolterken, also Low German, is diminutive for Walther, and another piece of household spirit of thepet nametype,Wolterkenglossed as "lares" and attested together with "chimken"and"hußnißken"inSamuel Meiger(1587)Panurgia lamiarum.[179][165][180][w][181]

Nis (Niß) is also explained to be a northern pet name for Nils.[139]

Apparel names

[edit]Under the classification of household spirit names based on appearance, a subcategory collects names based on apparel, especially the hat (classification C. a), under which are listedHütchen, Timpehut, Langhut,etc. and evenHellekeplein,[139]: 35) [182]which is one of the names of a cap orcloak of invisibility.[183]To this group belongs theLow Saxonformhôdekin(Low German:Hödekin) of the house sprite Hütchen fromHildesheim,which wears a felt hat (Latin:pileus).[x][188][189][190]Grimm also adds the namesHopfenhütel, Eisenhütel.[191]

Cat-shape

[edit]

It should be noted as a preface that the koboldHinzelmannor Hintzelmann[105]is completely distinguishable from the "literary" kobold Heinzelmännchen according to modern scholarship[3](cf.§ Heinzelmännchen).

And while the name Heinzelmann (Heinzelmännchen) is forged from diminutives of Heinrich,[161]more importantly, the names Hinzelmann, Heinzelman (orHinzelman, Hinzemännchen,etc.,) are names alluding to the kobold's frequent cat-like shape or transformation, and categorized Under type C "Appearance-based", subtype "beast-shape based names" in the HdA.[139]The analysis is expounded upon by Jacob Grimm, who notes that Hinze was the name of the cat in theReineke(German version ofReynard the Fox) so it was the common pet name for cats. Thus hinzelman, hinzemännchen are recognized as cat-based names, to be grouped withkatermann(fromkater"tom cat") which may be precursor totatermann.[193][139]

Thekatzen-veitnamed after a cat is categorized by Grimm as a "wood sprite", but also discussed under kobold,[194]and classed as a "cat appearance" type kobold name (category C b) inHdA.[139]Grimm localized thekatzen-veitatFichtelberg,[193]andPrateoriusalso recognized this as the lore of theVogtlandregion,[195]though Praetorius's work published (1692) under the pseudonym Lustigero Wortlibio claimskatzen-veitto be a famous "cabbage spirit" in the Hartzewalde (inElbingerode,now part ofOberharz am Brockenin theHarzmountains, cf. map).[195]

TheHitzelmannthat hauntedHudemühlen Castlein Lower Saxony was described at length by Pastor FeldmannDer vielförmige Hintzelmann(1704). As the title suggests, this Hinzelmann was a many and varied shapeshifter, transforming into a white feather,[196]or a marten, or a serpent.[197](cf.§ Animal form).

The kobold appears in the guise of a cat to eat thepanadabribe, in Saintine's version.[198]

Poltergeists

[edit]TheHdA’s category D consists of kobold names from their behavioural characteristics, and other than some non-German sprites discussed, these are mainly thepoltergeists,or noise-making spirits and names after their favourite dish.[139]The poltergeists include theklopfer( "knocker" ),[108][99]hämmerlein,[199]etc.[139]

Some poltergeists have been assumed to be named after their noise-making nature in the past, but whichHdAcategorizes otherwise as puppet names. So rather than takingpoppeleto be a form ofPuppe"doll", Grimm argued that the poltergeistpophart(orpopart)[202]andpoppele(regionally alsopopel, pöpel, pöplemann, popanz,etc.) were related to verbpopernmeaning to 'soft-knock or thump repeatedly' (orpopeln,boppeln"noisemaking"[200]), with a side meaning of a 'muffled (masked, covered-up) ghost to frighten children'.[203]

Likewise, though Grimm thoughtbutzwas reference to noise,[204]whilebutzseems to refer to a "tree trunk" and thus classed as A for doll-name byHdA.[139][131]

Rumpelstilzchenof Grimms' KHM No. 55 (as well as the Rumpelstilt mentioned byJohann Fischart[205]) are discussed as a poltergeist type of kobold by Grimm as well,[99]though not formally admitted under this poltergeist category of kobold names in the HdA. The name Rumpelstilts is composed ofRumpelmeaning "(crumpled) noise" andStilz, Stiltwith several meanings such as "stilts",a pair of poles used as extension of legs.[206]

Milk-lovers

[edit]In category D, there are names deriving from their favorite food being the bowl of milk, namelynapfhans( "Potjack" )[99]and the Swissbecklimeaning "milk vat" (cf.§ Offerings and retributions).[139]

Heinzelmännchen

[edit]

The Heinzelmännchen of Cologne resemble short, naked men. Like typical house sprites, they were said to perform household chores such as baking bread, laundry, etc. But they remained beyond sight of humans.[207][208]According toErnst Weyden(1826), bakers in the city until the late 18th century never needed hired help because, each night, the kobolds known made as much bread as a baker could need. However, the people of the various shops could not suppress their curiosity at seeing them, and the schemes to see them. A tailor's wife strewed peas on the stairs to trip them so she could see them. Such endeavors caused the sprites to disappear at all the shops in Cologne, before around the year 1780.[210]

This house sprite is included as kobold, but is considered a literary retelling, based on the fact the knowledge about the sprite had been spread byAugust Kopisch's ballad (1836).[211]

Miscellaneous

[edit]Other house spirits categorized as "K. Other names" by theHdAaremönch,: 74 herdmannl,schrackagerl.[212]Themönchlore is widespread from Saxony to Bavaria.[213]

King Goldemar, king of dwarfs, is also re-discussed under the household spirit commentary by Grimm, presumably because he became a guest to the human king Neveling von Hardenberg at hisCastle Hardensteinfor three years,[214]making a dwarf sort of a household spirit on a limited-term basis.

For cognate beings of kobolds or house spirits in non-German cultures, see§ Parallels.

Characteristics

[edit]

The kobold is linked to a specific household.[215]Some legends claim that every house has a resident kobold, regardless of its owners' desires or needs.[216]The means by which a kobold enters a new home vary from tale to tale.

Should someone take pity on a kobold in the form of a cold, wet creature and take it inside to warm it, the spirit takes up residence there.[217]A tradition fromPerlebergin northern Germany says that a homeowner must follow specific instructions to lure a kobold to their house. They must go onSt John's Daybetween noon and one o'clock, into the forest. When they find an anthill with a bird on it, they must say a certain phrase, which causes the bird to transform into a small human. The figure then leaps into a bag carried by the homeowner, and they can then transfer the kobold to their home.[218]Even if servants come and go, the kobold stays.[215]

House kobolds usually live in the hearth area of a house,[219]although some tales place them in less frequented parts of the home, in the woodhouse,[220]in barns and stables, or in the beer cellar of an inn. At night, such kobolds do chores that the human occupants neglected to finish before bedtime:[219]They chase away pests, clean the stables, feed and groom the cattle and horses, scrub the dishes and pots, and sweep the kitchen.[221][222]Other kobolds help tradespeople and shopkeepers.

Kobolds are spirits and, as such, part of a spiritual realm. However, as with other European spirits, they often dwell among the living.[223][224]The spirit's doings, and how humans interact will be discussed further below (§ Activities and interactions)

Kobolds can take on the appearance of children, be dressed a certain way, or manifest as non-human animals, fire, humans, and objects.[223]This is further discussed below (§ Physical description)

Physical description

[edit]

There seems to be contradictory opinion on whether a kobold should be generally regarded as boyish looking, or more elderly and bearded. An earlier edition (1819) of theBrockhaus Enzyklopädiegives the childlike description,[225]however, a later edition (1885) amends to the view of an elderly looking kobold, with a beard.[226]Yet actual instances of a bearded household kobold seems to concentrate on one lone example.[227]

The lore that a kobold, when spotted is often seen as a young child wearing a pretty jacket is presented in GrimmsDeutsche Sagen(1816), No.71 "Kobold".[228]And a cherubic, winged child illustration occurs in the 1704 printed book narrative of the kobold,Hintzelmann(cf. right).

The bearded look was underscored byJacob Grimm'sDeutsche Mythlogiewhere the kobold was ascribed red hair and beard, without specific examples.[229][y]Simrock summarized that "they" (apparently applying broadly to dwarfs, house spirits, wood sprites, and subterranean folk tend to have red hair and red beard,[z]as well as red clothing.[230]The example ofPetermännchenof Schwerin[230]is a story that mentions its white beard,[231][aa]and an instance of a kobold from Mecklenburg, with long white beard and wearing a hood (Kapuze) mentioned by Golther[234]is in fact Petermännchen also.[235]Theklabautermannwhich some reckon to be a ship-kobold[236][237]has been purported to have a fiery red head of hair and white beard.[238]

On the kobold assuming the guise of small children, there is a piece of lore that the kobolds are the spirits of dead children and often appear with a knife that represents the means by which they were put to death.[239][240][241]Cf.§ True identity as child's ghost

Other tales describe kobolds appearing as herdsmen looking for work[217]and little, wrinkled old men in pointed hoods.[219]

One 19th century source claimed mine kobolds with black skin were seen by her and her husband multiple times. (cf.§ Visitors from mines).[91]

Red cap

[edit]Kobolds supposedly also tend to wear a pointy red hat, though Grimm acknowledges that the "red peaky cap" is also the mark of the Norwegiannisse.[229]Grimm mentions the spirit known ashütchen(meaning "little hat" offelt,[188]cf.§ Apparel names) immediately after, perhaps as an example of such a cap-wearer.

The kobold wearing a red cap and protective pair of boots is reiterated by, e.g.,Wolfgang Golther.[242]Grimm describes household spirits owning fairy shoes or fairy boots, which permits rapid travel over difficult terrain, and compares it to theleague bootsof fairytale.[243]

There is lore concerning the infant-sizedniss-puk(Niß Puk, Nisspukvar.Neß Puk,wherePukis cognate to Englishpuck) wearing (pointed) red caps localized in various part of the province ofSchleswig-Holstein,in northernmost Germany adjoining Denmark.[244][245][s]

Karl Müllenhoffprovided the "kobold" lore of theSchwertmannof Schleswig-Holstein,[248]in his collection of Schleswig-Holstein legends, this tale localized atRethwisch, Steinburg(Krempermarsch).[249]The Schwertmann was said to dwell in adönnerkuhle(ordonnerloch,[246]"thunder pit", i.e., pit in the ground said to be caused by lightning[250]), which Müllenhoff insists was a "large water pit".[ab][249]It would emerge from this pit-hole and perpetrate mischief on villagers, but could also (try to) be helpful. It could appear in the guise of fire, and appreciated the gift of shoes, though his burning feet quickly turns them into tatters.[249][ac]According to supposed eyewitness accounts by people inStapelholmthe Niß Puk[ad]was no larger than a 1 or 1 1/2 year old infant (some say 3-year old)[ae]and had a "large head and long arms, and small but bright cunning eyes",[af]and wore "red stockings and a long grey or green tick coat..[and] red, peaked cap".[ag][112][252]

The lore of the house koboldpuk[ah]was also current farther east inPomerania,including now PolishFarther Pomerania.[253]The kobold-niss-pukwas regarded as wearing a "red jacket and cap" in westernUckermark.[254]The tale ofpûkstold in Swinemünde (nowŚwinoujście)[ai]held that a man's luck ran out when he rebuilt his house and the blessing passed on to his neighbor who reused the old beams. The pûks was witnessed wearing acocked hat(aufgekrämpten Hut), red jacket with shiny buttons.[255]

Invisibility and true form

[edit]

The normal invisibility of theChimgen(orChim) kobold is explained in legend which tells of a female servant taking a fancy to her house's kobold and asking to see him. The kobold refuses, claiming that to look upon him would be terrifying. Undeterred, the maid insists, and the kobold tells her to meet him later—and to bring along a pail of cold water. The kobold waits for the maid, nude and with a butcher knife in his back. The maid faints at the sight, and the kobold wakes her with the cold water. And she never wished to see the Chimgen[173]ever again.[256][257]

In one variant, the maid urges her favourite kobold named Heinzchen to see him in his natural state, and is then led to the cellar, where she is shown a dead baby floating in a cask full of blood; years before, the woman had borne a bastard child, killed it, and hidden it in such a cask.[163][258][259]

True identity as child's ghost

[edit]Saintine follows the story above with a piece of lore that kobolds are regarded as (ghosts of) infants, and the tail ( "caudal appendage" ) that they have represent the knife used to kill them.[260]What Praetorius (1666) stated was that the goblin haunting a house often appeared in the guise of children with knives stuck in their backs, revealing them to be ghosts of children murdered in that manner.[239]

The lore that the kobold's true identity is the soul of a child who died unbaptized was current in the Vogland (including such belief held for the gutel of Erzgebirge).[16]Like the soul, the kobold can assume any shape, even "sheer fire".[261]

Cf. Grimm, the lore that unbaptized children becomepilweisse(bilwis)[aj][264]Also, thede:Irrlicht(≈ will-o'-the-wisp), calledDickepôtenlocally in the southern Altmark, were said to be the souls of unbaptized children.[265][269]

Goldemar's traces

[edit]AlthoughKing Goldemar(or Goldmar), a famous kobold fromCastle Hardenstein,had hands "thin like those of a frog, cold and soft to the feel", he never showed himself.[270]King Goldemar was said to sleep in the same bed with Neveling von Hardenberg. He demanded a place at the table and a stall for his horses.[270]The master ofHudemühlen Castle,where Heinzelmann lived, convinced the kobold to let him touch him one night.

When a man threw ashes and tares about to try to see King Goldemar's footprints, the kobold cut him to pieces, put him on a spit, roasted him, boiled his legs and head, and ate him.[271]

Fire phenomena

[edit]

The kobold is said to appear as an oscillating fire-pillar ( "stripe" ) with a part resembling a head, but appears in the guise of a black cat when it lands and is no longer airborne (Altmark,Saxony).[120]Benjamin Thorpe likens this to similar lore about thedråk( "drake" ) in Swinemünde (nowŚwinoujście), Pomerania.[120]

A legend from the same period taken fromPechüle,nearLuckenwald,says that adrak(apparently corrupted fromDrachemeaning "drake" or "dragon"[272]) or kobold flies through the air as a blue stripe and carries grain. "If a knife or a fire-steel be cast at him, he will burst, and must let fall what which he is carrying".[254]Some legends say the fiery kobold enters and exits a house through the chimney.[268]Legends dating to 1852 from westernUckermarkascribe both human and fiery features to the kobold; he wears a red jacket and cap and moves about the air as a fiery stripe.[254]Such fire associations, along with the namedrake,may point to a connection between kobold and dragon myths.[268]

Afire drakecould also refer to thewill-o'-the-wispduring theShakespeareanperiod.[273][274]And "fire drake" was used as shorthand fordråkof Pomerania[ak]by literary scholarGeorge Lyman Kittredge,[al]who went on to explain, that the German wisps, calledIrrlichtorFeuermann( "fiery man" ) are conflate with, or rather indistinguishable from the German fire-drakes (dråk).[275]To theIrrlichtis attached a folk belief about the fire-light being the soul of unbaptized children[277]a motif already noted for the kobold. And the cited story of theFeuermann(Lausitzlegend) explains it to be a wood-kobold (Waldkobold) which sometimes entered houses and dwelled in the fireplace or chimney, like theWendish"drake".[278]

But theHdAdoes not furnish kobold names for "fire" or "wisp", and instead,Dråk, Alf, Rôdjacktewhich are said to fly through air like an enflamed hay-pole (Wiesbaum) laden with grain or gold (according to Pommeranian lore)[279][280]have all been categorized under the "I dragon names" category.[281]The connection between the fiery drak and the dragon-associated name in the Austrian dialectTragerlforshooting staris commented on by Ranke.[280](cf.§ Animal formbelow for lore of kobolds hatching from eggs, thus leading to comparisons withbasilisksand dragons).

Animal form

[edit]Other kobolds appear as non-human animals.[223]FolkloristD. L. Ashlimanhas reported kobolds appearing as wet cats and hens.[217]

In Pomerania there are several tales specimens that a kobold,puk,orrôdjakte/rôdjacktehatches from a yolk-less chicken egg (Spâei, Sparei),[116][284]and in other tales, a kobold (aka "redjacket" ) appears in a cat's guise[285]or apukappears as a hen.[286][287]

The comparison is readily made to the legend of the hen-hatchedbasilisk,and Polívka makes further comparisons to lore involving hens and dragons.[288]

Thorpe has recorded that the people of Altmark believed that kobolds appeared as black cats while walking the earth.[289]The kobold Hinzelmann could appear as a blackmarten(‹See Tfd›German:schwartzen Marder) and a large snake.[105]: 111 [290]

One lexicon glosses the French term for werewolf,loup-garou,as kobold.[292]This is somewhat underscored by the remark thatwerewolftransformation was considered an ability of sorcerers withunibrow,which was a physical mark shared with the Schratel spirit (as wood sprite).[293]

These do not comprise an exhaustive list of what forms the kobold can take on. Thehinzelmannbesides the cat appears as a "dog, hen, red or black bird, buck goat, dragon, and a fiery or bluish form", according to an old encyclopedic entry.[226]Ranke (1910) gave a similar list for kobold transformations which includesbumblebee(Hummel).[261]

Activities and interactions

[edit]Offerings and retributions

[edit]A kobold expects to be fed in the same place at the same time each day.[221]

But it is known that the kobold becomes extremely dedicated to caring for its household, performing the chores and services in its maintenance, as in the case of the Hinzelmann.[294]The association between kobolds and work gave rise to a saying current in 19th-century Germany that a woman who worked quickly "had the kobold" ( "sie hat den Kobold" ).[295][296]

Legends tell of slighted kobolds becoming quite malevolent and vengeful,[219][221]afflicting errant hosts with supernatural diseases, disfigurements, and injuries.[297]Their pranks range from beating the servants to murdering those who insult them.[298][299]

In the story of the Chimmeken of theMecklenburg Castle,(supra,dated 1327 given by Kantzow) the milk customarily put for the sprite by the kitchen was stolen by a kitchen-boy (Küchenbube), and the spirit consequently left the boy's dismembered body in a kettle of hot water.[110][301][161]In comparison, a more amicablepückanecdotally served monks at Mecklenburg monastery, bargaining for multicolored tunic with lots of bells in return for his services.[303]

A similar story of the vengefulHüdeken[188](var.Hütgin[am]) occurs in a chronicle ofHildesheim,c. 1500.[305][306][308][310][311]A preceding tale whereHüdekenserves as messenger following an assassination of c. 1132 explains the historical background, whereby the Bishop of Hildesheim assumes control of Winzenburg Castle.[312]TheHüdeken(also Hödekin) exacted veneance on the kitchen boy of the castle who splashed filthy water[316]by strangling the lad in his sleep and leaving the severed body parts cooking in a pot over the fire. When the head cook complained about the prank, the Hüdeken squeezed venomoustoadblood onto the meat being prepared for the bishop. Later he led the cook to an illusory bridge plunging him into the moat.[319][320][322][323]Some versions add that the Bishop in the end used the power of his spells (Beschwörung) to get rid of the Hödeken.[325]

According toMax Lüthi,the household spirits' being ascribed such abilities reflect the fear of the people who believe in them.[297]

The bribe left to the household spirit was a combination of milk and bread according to multiple sources. In the printed edition ofDer vielförmige Hintzelmann(1704), Hintzelmann was supposed to be provided with a bowl of sweet milk with white bread crumbled over it (as illustrated in the book).[326][327]The offering was to be milk andSemmel(bread roll) also according to a lexicon forAltmark.[329]The offering was described aspanada(bread [and milk] soup) in the French retelling by Saintine.[177]

NovelistHeinrich Heinenoted in connection with the present (Hildesheim) tale that the favourite food was thegruelfor the Scandinaviannisse.[330]

Other dairy lore

[edit]As a sort of the reverse of the offering, one tradition claims that the kobold will strew wood chips (sawdust,Sägespäne) about the house and putting dirt or cow manure in the milk cans. And if the master of the house leaves the wood chips and drinks the soiled milk, the kobold is pleased and takes up residence at the household.[295][331][332]

The bribe put out for the kobold may be butter, for example, the Niß Puk of the Bombüll farmstead atWiedinghardein Schleswieg-Holstein would tend to themilchcows,but demanded a morsel of butter on a plate each evening, and the Puk would choke the best milking cow if it was not provided.[333]

According to the lore fromSouth Tyrol(now part of Italy), the Stierl farmstead atTemplate:Ilmmexperienced the trouble where the farmer's wife could not makebutterfor all her churning in the bucket (Kübel).[an]The farmer decided it was the doings of a kobold, and went down to the basement where lived Kröll Anderle who was learned in the magic books,[ao]and Anderle gave instructions to dip a glowing hot skewer into the liquid while churning the bucket under the eaves, which succeeded. But the kobold driven out repaid the farmer's wife with a hot log leaving her a permanent burn injury.[334]

Good-evil duality

[edit]Archibald MacLarenhas attributed kobold behaviour to the virtue of the homeowners; a virtuous house has a productive and helpful kobold; a vice-filled one has a malicious and mischievous pest. If the hosts give up those things to which the kobold objects, the spirit ceases its annoying behaviour.[335]Hinzelmann punished profiligacy and vices such as miserliness and pride;[336]for example, when the haughty secretary of Hudemühlen was sleeping with the chamber maid, the kobold interrupted a sexual encounter and hit the secretary with a broom handle[337][338]King Goldemar revealed the secret transgressions of clergymen, much to their chagrin.[270]

Even friendly kobolds are rarely completely good,[339]and house kobolds may do mischief for no particular reason. They hide things, push people over when they bend to pick something up, and make noise at night to keep people awake.[340][341]The kobold Hödeken of Hildesheim roamed the walls of the castle at night, forcing the watch to be constantly vigilant.[320]A kobold in a fishermen's house on theWendish Spree,about aGerman mile(7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi)) from theKöpenickquarter of Berlin, reportedly moved sleeping fishermen so that their heads and toes lined up.[342][343]King Goldemar enjoyed strumming the harp and playing dice.[270]

Good fortune

[edit]A kobold can bring wealth to his household in the form of grain and gold.[217]In this function it often is calledDrak.A legend fromSaterlandandEast Frieslandtells of a kobold called theAlrûn(which is the German term formandrake). In the tale from Nordmohr/Nortmoor,E. Friesland, now Low Saxony) despite standing only about a foot tall, the creature could carry a load of rye in his mouth for the people with whom he lived and did so daily as long as he received a meal of biscuits (Zwieback) and milk.[125][145]Kobolds bring good luck and help their hosts as long as the hosts take care of them.

The kobold Hödekin, who lived with the bishop of Hildesheim in the 12th century, once warned the bishop of a murder. When the bishop acted on the information, he was able to take over the murderer's lands and add them to his bishopric.[320]

The house-spirit in some areas were calledAlrûn( "mandrake" ), though this was also the name of a trinket sold in bottles,[344]which instead of being genuine mandrake could be any doll shaped from some plant root.[141]And the sayingto have an Alrûn in one's pocketmeans "to have luck at play".[145]However, kobold gifts may be stolen from the neighbours; accordingly, some legends say that gifts from a kobold are demonic or evil.[217]Nevertheless, peasants often welcome this trickery and feed their kobold in the hopes that it continue bringing its gifts.[51]A family coming into unexplained wealth was often attributed to a new kobold moving into the house.[217]

Eradication

[edit]Folktales tell of people trying to rid themselves of mischievous kobolds. In one tale, a man with a kobold-haunted barn puts all the straw onto a cart, burns the barn down, and sets off to start anew. As he rides away, he looks back and sees the kobold sitting behind him. "It was high time that we got out!" it says.[345]A similar tale fromKöpenicktells of a man trying to move out of a kobold-infested house. He sees the kobold preparing to move too and realises that he cannot rid himself of the creature.[346]

Exorcismby a Christian priest works in some tales; in certain versions of the Hödekin in the kitchen of the castleenfeoffedto the Bishop of Hildesheim, the bishop managed to exorcise Hödekin using church-spells.[325][314][ap]The attempts to expel the Hintzelmann from the Castle Hudemühlen by a nobleman and later by an exorcist trying to use a book of holy spells were foiled, it later left of its own will.[347]

Insulting a kobold may drive it away, but not without a curse; when someone tried to see his true form, Goldemar left the home and vowed that the house would now be as unlucky as it had been fortunate under his care.[348]

Other specialized kobolds

[edit]Other than the mine spirit kobold above, there are others "house spirits" that haunt shops, ships, etc. places of various professions.

TheKlabautermann(cf. also§ Klabautermannbelow) is a kobold from the beliefs of fishermen and sailors of theBaltic Sea.[349]Adalbert Kuhnrecognized in northern Germany the formKlabåtersmanneken(syn.Pûkse) which hauntedmillsand ships, subsisted on the milk put out for them, and in return performed chores such as milking cows, grooming horse, helping the kitchen, or scrubbing the ship.[350]

Thebieresel,sometimes called a type of kobold live in breweries and the beer cellars of inns or pubs, bring beer into the house, clean the tables, and wash the bottles, glasses and casks. The family must leave a can of beer,[351][352]or a portion of their supper for thebieresel(cf.Hödfellow) and must treat the kobold with respect, never mocking or laughing at the creature.

Klabautermann

[edit]

TheKlabautermannis a spirit that dwells in ships, according to the beliefs of the seafaring folk around theBaltic Seain Germany and Netherlands, etc.[353]The spirit has been classed as a ship-kobold[237][236]and is sometimes even called a "kobold".[353]The Klabautermann typically appears as a small, pipe-smoking humanlike figure wearing a red or grey jacket,[354]or yellow attire, wearing nightcap-style sailor's hat[236]or a pair of yellow hoses andriding boots,and a "steeple-crowned" pointy hat.[238]

Klabautermanns may be benevolent and aid the ship's crews in their tasks, but also be a menace or nuisance.[354][357]For example, it may help pump water from the hold, arrange cargo, and hammer at holes until they can be repaired.[357]But they can pull pranks with the tackle lines as well.[357]

The Klabautermann is associated with the wood of the ship on which it lives. It enters the ship via the wood used to build it, and it may appear as a ship's carpenter.[354]It is said that if an unbaptized child is buried in a heath under a tree, and that timber is used to build a ship, the child's soul will become the klabautermann which will inhabit that ship.[237]

Parallels

[edit]Kobold beliefs mirror legends of similar creatures in other regions of Europe, and scholars have argued that the names of creatures such asgoblinsandkaboutersderive from the same roots askobold.This may indicate a common origin for these creatures, or it may represent cultural borrowings and influences of European peoples upon one another. Similarly, subterranean kobolds may share their origins with creatures such asgnomesanddwarves.

Sources equate the domestic kobold with creatures such as the Danishnis[331][314]and Swedishtomte,[358]Scottishbrownie,[331][359]the Devonshirepixy,[359]Englishboggart,[314]and Englishhobgoblin.[331]

If the definition of kobold is extended beyond the house sprite and extended to mine spirits and subterranean dwellers (akagnomes), then the parallels to mine-kobolds can be recognized in the Cornishknockerand the Englishbluecap[360]as well as the Welshcoblynau.[361]

Irish writerThomas Keightleyargued that the German kobold and the Scandinaviannispredate the Irishfairyand the Scottishbrownieand influenced the beliefs in those entities, but modern folkloristRichard Mercer Dorsonnoted Keightley's bias as a strong adherent of Grimm, embracing the thesis of regarding ancient Teutonic mythology as underlying all sorts of folklore.[362]

British antiquarian Charles Hardwick ventured a theory that the spirits like the kobold in other cultures, such as the Scottishbogie,Frenchgoblin,and EnglishPuckwere also etymologically related.[364]In keeping with Grimm's definition, thekobaloiwere spirits invoked (i.e., used asinvective?) by such tongue-wagging rogues.[74]

A parallel to thebieresel[non-primary source needed]may be the English legend, first appearing in the 19th century, concerning a house spirit namedHodfellowthat resided at theFremlin's BreweryinMaidstone,Kent,England who was wont to either assist the company's workers or hinder their efforts depending on whether he was being paid his share of the beer.[365]

Thezashiki-warashi(lit. 'sitting-room lad') ofJapanese folkloreparallels the kobold.[366][367]Many points of commonality have been pointed out, for instance, the house inhabited by the sprite flourishes, but will fall to ruin once it leaves. Thewarashiis also of prankish nature,[368]but does not actually help out with household chores.[368]Both sprites can be appeased by offerings of favorite food, which isazuki-meshi( "adzukirice ") for the Japanese version.[368]

In culture

[edit]Literary references

[edit]German writers have long borrowed from German folklore and fairy lore for both poetry and prose. Narrative versions of folktales and fairy tales are common, and kobolds are the subject of several such tales.[369] The kobold is invoked byMartin Lutherin hisBible,translates the HebrewlilithinIsaiah34:14 askobold.[370][371]

InJohann Wolfgang von Goethe'sFaust,the kobold represents theGreek elementof earth.[372]This merely goes to show that Goethe saw fit to substitute "kobold" for the gnome of the earth, one ofParacelsus's four spirits.[373]InFaustPart II, v. 5848, Goethe usesGütchen(syn.Güttelabove) as synonym for his gnome.[95][374]

Theatrical and musical works

[edit]A kobold is musically depicted inEdvard Grieg's lyric piece, opus 71, number 3.

Der Kobold,Op. 3, is also Opera in Three Acts with text and music bySiegfried Wagner;his third opera and it was completed in 1903.

The kobold charactersPittiplatschoccurs in modern East German puppet theatre..Pumucklthe kobold originated as a children's radio play series (1961).

Games and D&D literature

[edit]Kobolds also appear in many modern fantasy-themed games likeClash of ClansandHearthstone,usually as a low-power or low-level enemy. They exist as a playable race in theDark Age of Camelotvideo game. They also exist as a non-playable rat-like race in theWorld of Warcraftvideo game series, and also feature in tabletop games such asMagic: The Gathering.InDungeons & Dragons,thekoboldappears as an occasionally playable race of lizard-like beings. InMight and Magicgames (notablyHeroes VII), they are depicted as being mouse-dwarf hybrids.

Fantasy novels and anime

[edit]The fantasy novelRecord of Lodoss Waradapted into anime depicts kobolds as dog-like, based on earlier versions ofDungeons & Dragons,resulting in many Japanese media depictions doing the same.

In the novelAmerican Gods,byNeil Gaiman,Hinzelmann is portrayed as an ancient kobold[48]who helps the city of Lakeside in exchange for killing one teenager once a year.

In the novelThe Spirit RingbyLois McMaster Bujold,mining kobolds help the protagonists and display a fondness for milk. In an author's note, Bujold attributes her conception of kobolds to theHerbert HooverandLou Henry Hoovertranslation ofDe re metallica.

See also

[edit]- Friar Rush– Medieval Low German legend

- Gremlin– Fictional mischievous creature

- Hödekin– Sprite of German folklore

- Kobold (Dungeons & Dragons)– Fictional species in Dungeons & Dragons

- Gütel– Domestic and mining sprite from German folklore

- Niß Puk– Legendary creature in Danish, Frisian and German mythology

- Yōsei– Spiritlike creature from Japanese folklore

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^i.e., cut up into pieces and left in a kettle or pot.

- ^Grimm's version combines multiple sources, includingErasmus Francisci(1690) which includes the tale under the header of "kobold".

- ^It is not a sprite of Hildesheim strictly speaking. The events of c. 1130 made a count lose his fiefdom and Winzenburg castle, which was then awarded to the bishopric of Hildesheim.

- ^Additional examples exist if the bergmännlein (mountain, or mine spirits) are admitted as "kobolds".

- ^abStith-Thompson'smotif indexF405.11. "House spirit leaves when gift of clothing is left for it".

- ^Francisi is one of the sources for Grimm'sDSNo. 74Hütchen'.

- ^And since Francisci dates much later than the Pastor Feldmann to have known the work, it must have been interpolated by the anonymous editor.

- ^Müller-Fraureuth (1906) wrote that the formkobesurvives in modern German "Schweinekoben",[53]meaning "pig stall", and that the true original etymology contained the stem-Holdas a name for "demon".[53]

- ^Yiddish linguistPaul Wexler(2002), discussing Germanhold"beautiful" tangentially notes the etymology ofkoboldcould derive fromkoben"pigsty"+hold"stall spirit". He also suggests -Hold for demon and "Holle" may be grouped as related terms, and notes pre-Christian tradition of girls offering twisted knots of hair toFrau Holle;in the subsequent entry he notes twisted bread (challah bread) may have something to do with Frau Holle, but this origin is masked by using a spelling suggestive of Hebrew origins.[57]

- ^If there were attested OHG form, they would not need to be reconstructed.

- ^Konrad's poem above seems to be a more complicated double metaphor to theluhs(Luchs,"lynx", conceived of as ahybridof fox and wolf, and therefore unable to breed) deriding someone as reproductivelysterileand deceitful, just like a kobold doll.[63]

- ^Although Grimm'sTeutonic Mythologyglossed the wordcobalusas "Schalk"and this got translated as 'rogue',Liddell and Scottactually gives "impudent rogue, arrant knave",[74]which is pointed out as being dated: here, "joker" would be appropriate in present-day colloquy.[75]Others suggest "trickster".[76]

- ^Grimm also characterizes kobold as a "tiny tricky home-sprite" and comments at length on its laughter.[24]Note that the cobali are described as having the habit to "mimic men", "laugh with glee, and pretend to do much, but really do nothing", and "throw pebbles at the workmen" doing no real harm.[26]

- ^-lein, -chen are the commonest German diminutives

- ^The source was Agricola'sDe animatibus(1549), but Grimm attributed it to a different work,de re metallica Libri XIIdue to confusion. Basically Agricola wrote in Latin any German terms were Latinized or Graecized (thus "cobalos" ).[25]}[26]So to know the actual German terms ( "kobel" ), one needed to consult the glossary[87]The glossary was later attached to a 1657 omnibus edition consisting of an excerpt ofDe animatibusadded tode re metallicain XII books, which is clearly Basel 1657 edition Grimm is citing.[27]

- ^For Further description of "mine kobolds" akaBerggeist[er]given by Britten, cf.Gnome#Communication through noises.

- ^Mr. Kalodzky, who taught at the Hungarian School of Mines.

- ^Compare published map by Schäfer et al. (2000)[6]

- ^abNiss is categorized E "pet name",[139]while Puck is considered G. "devil name" by the HdA.[166]

- ^The remaining categories are: F.Rufname(proper first name) G. Devil-name (incl. Puck) H. Literary name (e.g. Gesamtname), I. Dragon name (incl. Alf, Alber, Drak, Alrun, Tragerl, Herbrand K. Different names (Mönch).

- ^Thorpe cites Grimm'sDMso he realizes this is a term for a plant root (kräuzer).[146]

- ^In the south, "Heinzelmännchen"confusingly carries the different meaning of mandrake root (‹See Tfd›German:Alraun,Alraunwurzel).[3]Perhaps this explains why Arrowsmith lists mandrake names (Allerünken, Alraune, Galgenmännlein) as synonyms for kobold in the south.[147]

- ^Classified as "E. pet name (German:Kosenamen)" type names in theHdA.

- ^Rather thanHödekinbeing strictly correct, the vowel "ö" actually occurs as Early modern German "o with e above" in Praetorius, and transcribed that way by Wyl.

- ^A cursory search of GrimmsDSdo not reveal bearded household kobolds. The legends with bearded manikins are No. 37 "Die Wichtlein [oder Bergmännlein]" (mine spirit), 145 Das Männlein auf dem Rücken (manikin forces piggyback, from Praetorius), 314 Das Fräulein vom Willberg (in a cave, one with a beard grown through stone table).

- ^Simrock also registers connection with the red hair and beard of Donar/Þórrgod of thunder.

- ^Simrock connects "Hans Donnerstag" with Donner/thunder, but this brief tale concerns a suitor who keeps his name secret (motif ofRumpelstiltskin[232]) and the tale gives no description of her finacé whom she discovers to be a dwarf or a "subterranean".[233]

- ^"Wassergrube",p. 601.

- ^Note that the English translation of the essay "tales from his own collection, no. 346{ [sic].. "is a misprint for No. 348"Der Teufel in Flehdeis localized inRehm-Flehde-Bargenin theDithmarschen.[251]In the Beowulf essay Müllenhoff also cites "Der Dränger"(" the presser ", No. 347), said to breach dams, localized around the mouth of theEider,close to e.g. Stapelholm.

- ^Müllenhoff:‹See Tfd›German:Leute aus.. Stapelholm, die den Niß Puk gesehen haben.. "

- ^Müllenhoff, "430. Die Wolterkens":"nicht größer als ein oder anberthalbjähriges Kind sei. Andre sagen, er sei so gross wie ein dreijähriges".

- ^Müllenhoff: "Er hat einen grosen Kopf und lange Arme, aber kleine, helle, kluge Augen".

- ^Müllenhoff: "trägt er ein paar rothe Strümpfe,.. lange graue oder grüne Zwillichjacke und.. rothe spitze Mütze ".

- ^Alsodrak

- ^Cf. Drak lore of this city under§ Fire phenomena.

- ^The "Pilweise of Lauban"[262]is regarded as being related to the stable-kobold,schretelein.[263]Cf.Schrat.

- ^Kitteredge citesJahn (1886)Volkssagen aus Pommern und Rügen', pp. 105ff, 110, etc.

- ^Just as Ashliman used "drake" for the Pomeraniandrak.

- ^"Hütgin" used jocularly as salutation to wife: "tibi uxorem.. commendo".Variant spelling ignored in Eng. tr.

- ^This is similar to the lore that the mine-kobold (properlykobel) was thought responsible for swapping silver with then worthless cobalt; the silver-mining operation also involved used of the bucketKübel,which Muerller-Fraureuth conjecturesd was the root of the sprite's namekobel.[53]

- ^Of this character, there is a separate legend, "109. Vom Kröll Anderle" is told in Heyl, p. 290.

- ^Not in the Praetorius's version, quoted by Heine.[221]

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^abEvans, M. A. B.(1895)."The Kobold and the Bishop of Hidesheim's Kitchen-boy".Nymphs, Nixies and Naiads: Legends of the Rhine.Illustrated by William A. McCullough. New York: G.P. Putnam's sons. p. 33.ISBN9780738715490.

- ^abcdeGrimms;Hildebrand, Rudolf(1868).Deutsches Wörterbuch,Band 5, s.v. "Kobold"

- ^abcdeKluge, Friedrich;Seebold, Elmar,eds. (2012) [1899]."Heinzelmännchen".Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache(25 ed.). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 406.ISBN9783110223651.

- ^abcdefWeiser-Aall, Lily(1987) [1933]. "Kobold". InBächtold-Stäubli, Hanns[in German];Hoffmann-Krayer, Eduard(eds.).Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens.Vol. Band 5 Knoblauch-Matthias. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 31–33.ISBN3-11-011194-2.

- ^Lecouteux, Claude(2016)."BERGMÄNNCHEN (Bergmännlein, Bergmönch, Knappenmanndl, Kobel, Gütel; gruvråin Sweden) ".Encyclopedia of Norse and Germanic Folklore, Mythology, and Magic.Simon and Schuster.ISBN9781620554814.

- ^abcdefSchäfer, Florian[in German];Pisarek, Janin[in German];Gritsch, Hannah (2020)."2. Die Geister des Hauses. § Der Kobold".Hausgeister!: Fast vergessene Gestalten der deutschsprachigen Märchen- und Sagenwelt.Köln:Böhlau Verlag.p. 34.ISBN9783412520304.

- ^abHeinz- and Hinzelmann once treated as interchangeable by Grimm, and by others likeThomas Keightleyfollowing his footsteps. However, and the entry for "Heinzelmänchen" in theEtymologisches Wörterbuchexplains the distinction.[3]Heinzelmänchen, is in the "kobold" article forHandwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens,but classified neither under "C, Appearance-based names" with the cat-name Hinzelmann nor under "E pet names/shortened affectionate names of people", but under H. literary names.[4]Lecouteux's dictionary gives "Heinzelmännchen" as one "coined from first names", and groups it with Wolterken, Niss, Chimken (all kobold names),[5]in contrast to HdA. Note a recent publication has a "Kobold" chapter has included a map of Germany plotting subtype kobold names for each region, but the Cologne area is left blank.[6]

- ^abRanke, Kurt(1987) [1936]. "Schrat, Schrättel (Schraz, Schrätzel)". InBächtold-Stäubli, Hanns[in German];Hoffmann-Krayer, Eduard(eds.).Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens.Vol. Band 7 Pflügen-Signatur. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1285–1286.ISBN3-11-011194-2.

- ^abRanke (1936),p. 1288.

- ^The area is described as "southeastern Germany", with the cited sources pointing to the general area of Northern Bavarian including theUpper PalatinateontoVogtlandwhich extends to Thuringia.[9](Cf.Schratand§ Cretin namesbelow)

- ^abLurker, Manfred (2004)."Fairy of the Mine".The Routledge Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, Devils and Demons(3 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 103.ISBN0-415-34018-7.

- ^The Grimms abridge the single printed source,Der vielförmige Hintzelmann,Feldmann (1704).

- ^abcFentsch, Eduard (1865)."4ter Abschnitt. Volkssage und Volksglaube in Oberfranken".InRiehl, Wilhelm Heinrich(ed.).Bavaria: Landes- und volkskunde des königreichs Bayern.Vol. 3. München: J. G. Cotta. pp. 305–307.

- ^Clothing to theschretzchenofKremnitzmühle[13]

- ^abcMeiche (1903)"389. Noch mehr von Heugütel", pp. 292–293

- ^abRanke (1910),pp. 149–150.

- ^Slippers to theheugütel(heigidle) of Erzgebirge/Vogtland.[15][16]

- ^abcdefLexer(1878). "kóbolt, kobólt",Mittelhochdeutsches Handwörterbuch

- ^abGrimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),pp. 500–501.

- ^abcGrein, Christian W. M.(1861–1864)Sprachschaß der angelsächsischen Dichter1:167, quoted also in GrimmsDW"Kobold" III. 2).

- ^Since it is only attested only as "idolum" (in one of Diefenbach's sources), etc. among MHG glosses.[18]But the Anglo-Saxon formcofgoduglossed as "penates"(household deity) bolsters the possibility thatkoboltor some MHG cognate form corresponded to it.[18][20]

- ^Trochus, Balthasar (1517). "Sequuntur multorum deorum nomina..".Vocabulorum rerum promptuariu[m].Leipzig: Lottherus. p. A5.

- ^abTrochus, Balthasar (1517),page A5[22]reads "lares foci sunt vulgo kobelte" as requoted in GrimmsDW"Kobold" III. 2).[2]Laresbeing household or hearth goddesses. The same work has an entry for "Lares/Penates",pp. O5–O6, discussing the household sacred beings using a mix of German, and including mention ofHutchenas a small shack or hutch.

- ^abcGrimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),p. 502.

- ^abAgricola, Georgius(1614). "37". In Johannes Sigfridus (ed.).Georgii Agricolae De Animantibus subterraneis.Witebergæ: Typis Meisnerianis. pp. 78–79.

- ^abcdAgricola, Georgius(1912).Georgius Agricola De Re Metallica: Tr. from the 1st Latin Ed. of 1556 (Books I–VIII).Translated byHoover, Herbert ClarkandLou Henry Hoover.London: The Mining Magazine. p. 217, n26.;Second Part,Books IX–XII

- ^abAgricola, Georgius(1657) [1530]."Animantium nomina latina, graega, q'ue germanice reddita, quorum author in Libro de subterraneis animantibus meminit".Georgii Agricolae Kempnicensis Medici Ac Philosophi Clariss. De Re Metallica Libri XII.: Quibus Officia, Instrumenta, Machinae, Ac Omnia Denique Ad Metallicam Spectantia, Non Modo Luculentissime describuntur; sed & per effigies, suis locis insertas... ita ob oculos ponuntur, ut clarius tradi non possint.Basel: Sumptibus & Typis Emanuelis König. p. [762].

Dæmonum:Dæmon subterraneus trunculentus:bergterufel;mitisbergmenlein/kobel/guttel

- ^AgricolaDe Animantibus subterraneis,[25]Eng. tr.,[26]compared with Latin-German gloss to the work.[27]

- ^Grimm,Deutsches Wörterbuch,Band 5, s.v. "Kobold"

- ^GrimmDW"kobold", I gives definition, III gives origins.[29]

- ^abLexer, Max (1872)Mittelhochdeutsches Handwörterbuchs.v. "kóbolt, kobólt"

- ^abFrancisci, Erasmus(1690).Der Höllische Proteus; oder, Tausendkünstige Versteller: vermittelst Erzehlung der vielfältigen Bildverwechslungen erscheinender Gespenster, werffender und poltrender Geister, gespenstischer Vorzeichen der Todes-Fälle, wie auch andrer abentheurlicher Händel, arglistiger Possen, und seltsamer...Nürnberg: In Verlegung W.M. Endters. p. 793 (pp. 792–798).

- ^Kiesewetter (1890),pp. 9–10.

- ^Feldmann (1704),Cap. VI, p. 77 And Cap. II, p. 27, where "Feld-Teufel.. Kobolte" are mentioned.

- ^Feldmann (1704),pp. 230, 251, 254.

- ^Praetorius (1666),p. 359;Praetorius (1668),p. 311

- ^abStieler, Kaspar von(1705) s.v.Spiritus familiaris",Des Spatens Teutsche Sekretariat-Kunst2:1060: "ein Geist in eineme Ringe, Gäcklein oder Haaren"

- ^s.v. "*Procubare",Diefenbach, Lorenz(1867).Novum glossarium latino-germanicum,p. 304. Citing '7V. vrat. sim.9

- ^Diefenbach, Lorenz(1867)Novum glossarium latino-germanicum"Quellen",p. xxii

- ^Cited in Lexer, "kobolt".[18]

- ^Notker(1901).Fleischer, Ida Bertha Paulina[in German](ed.).Die Wortbildung bei Notker und in den verwandten Werken: eine Untersuchung der Sprache Notkers mit besonderer Rücksicht auf die Neubildungen...Göttingen: Druck der Dieterich'schen Univ.-Buchdruckerei (W. Fr. Kaestner). p. 20.

- ^abGrimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),p. 500.

- ^Old High Germanhûsingis glossed as LatinpenatesinNotker,[41]cited by Grimm.[42]

- ^Weiser-Aall (1933),p. 29.

- ^Franz, Adolf ed. (1906), Frater Rudolfus (c. 1235-1250)De officio cherubyn,p. 428

- ^Johansons, Andrejs[in Latvian](1962)."Der Kesselhaken im Volksglauben der Letten".Zeitschrift für Ethnologie.87:74.

- ^abSchrader, Otto(1906)."Aryan Religion".Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics.Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 24.;(1910) edition

- ^abMüller-Olesen, Max F. R. (2012)."Ambiguous Gods: Mythology, Immigration, and Assimilation in Neil Gaiman'sAmerican Gods(2001) and 'The Monarch of the Glen' (2004) ".In Bright, Amy (ed.)."Curious, if True": The Fantastic in Literature.Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 136 and note15.ISBN9781443843430.

- ^Schrader (2003) [1908], p. 24[47]also quoted by Olesen (2012),[48]but the latter appears to be synthesis and not direct quoting.

- ^MacLaren (1857),p. xiii.

- ^abcdDowden, Ken(2000).European Paganism.London: Routledge. pp. 229–230.ISBN0-415-12034-9.;reprinted in: Dowden, Ken(2013) [2000].European Paganism.Taylor & Francis. pp. 229–230.ISBN9781134810215.

- ^Also repeated in other sources such as MacLaren[50]and Dowden (2000)[51]

- ^abcdefMüller-Fraureuth, Karl (1906)."Kap. 14".Sächsische Volkswörter: Beiträge zur mundartlichen Volkskunde.Dresden: Wilhelm Baensch. pp. 25–26.ISBN978-3-95770-329-3.

- ^abcGlasenapp (1911),p. 134.

- ^Also Glasenapp (1911) surveys the etymological considerations,[54]and Kretschmer (1928) weighing in on kobold vs. gnome (mine spirit) names (virunculus montanos, etc.) as cited elsewhere.

- ^abJohansson, Karl Ferdinand (1893)."Sanskritische Etymologien".Indogermanische Forschungen.2:50.

- ^Wexler, Paul(2002).Trends in Linguistics:Two-tiered Relexification in Yiddish: Jews, Sorbs, Khazars, and the Kiev-Polessian Dialect.Walter de Gruyter.ISBN3-11-017258-5.p. 289.

- ^Kluge, Friedrich;Seebold, Elmar,eds. (2012) [1899]."Kobold".Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache(25 ed.). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 510.ISBN9783110223651.

- ^Namely throughGrein(1861–1864), which the Grimms knew and quoted for the etymology of kobolt as "hauses walten"in the Grimms' dictionary entry for" Kobold ", II b).

- ^Kretschmer, Paul(1928)."Weiteres zur Urgeschichte der Inder".Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete der indogermanischen Sprachen.55.p. 89 and p. 87, n2.

- ^Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),p. 500: "possibly earlier, if only we had authorities". Cf. note 4.

- ^abcGrimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),p. 501.

- ^Katalog der Texte. Älterer Teil (G - P),s.v., "KoarW/7/15",citing Schröder 32, 211. Horst Brunner ed.

- ^Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),pp. 500, 501 "for fun"; and notes, vol. 4,Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1888),p. 1426

- ^abSimrock, Karl Joseph(1887) [1855].Handbuch der deutschen Mythologie: mit Einschluss der nordischen(6 ed.). A. Marcus. p. 451.

- ^Simrock: "zuletzt mehr zum Scherz oder zur Zierdelately more as joke or for decor "[65]

- ^abGrässe, Johann Georg Theodor(1856)."Zur Geschichte des Puppenspiels".Die Wissenschaften im neunzehnten Jahrhundert, ihr Standpunkt und die Resultate ihrer Forschungen: Eine Rundschau zur Belehrung für das gebildete Publikum.1.Romberg: 559–660.

- ^Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),p. 501, citingWahtelmaere140, "rihtet zuo mit den snüeren die tatermanne" alludes to it being "guid[ed].. with strings".

- ^Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),pp. 501–502.

- ^Keightley (1850),p. 254.

- ^Grimm (1875),1:415:lachen als ein kobold,p. 424 "koboldische lachen";Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),p. 502 "laugh like a kobold", p. 512 tr. as "goblin laughter".

- ^Other examples: Satire of the clergy as "wooden bishop", or "wooden sexton".[65]A man in silence is likened to a mute doll,[62]hence the comparison of a kobold struck dumb and the wooden bishop (citing Mîsnaere inAmgb(Altes meistergesangbuchin Myllers sammlung) 48a). A man hearing confession compared to kobold, in aFastnachtspiel.[2]

- ^Weiser-Aall (1933),pp. 31–32.

- ^abLiddell and Scott (1940).A Greek–English Lexicon.s.v. "koba_l-os, ho".Revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.ISBN0-19-864226-1.Online version retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^Tordoff, Robert (2023).Aristophanes: Cavalry.Leipzig: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 46–47.ISBN9781350065703.

- ^Hawhee, Debra (2020).Rhetoric in Tooth and Claw: Animals, Language, Sensation.University of Chicago Press. p. 60.ISBN9780226706771.

- ^Horton, Michael(2024)."Chapter 3. Shaman to Sage § Assimilation to an Erstwhile Minor Shamanic Deity".Shaman and Sage: The Roots of "Spiritual but Not Religious" in Antiquity.Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.ISBN9781467467902.

- ^Lockwood, William Burley(1987).German Today: The Advanced Learner's Guide.Clarendon Press. pp. 29, 32.ISBN9780198158042.

- ^Aristotle describes an owl as both a mime and akobalos( "trickster" ).[77]Older German-English dictionaries defineSchalkas "rogue" or "wag", again, dated terms, whereas "scamp,joker "is given by a later linguist.[78]Glasenapp believedcobalusmeant a professional joker, buffoon, sycophant.[54]

- ^Grimm & Stallybrass tr. (1883),p. 500;Grimm (1875),pp. 415–416

- ^abKiliaan, Cornelis(1620) [1574]Etymologicum teutonicae linguaes.v.kabouter-manneken

- ^Grimm,DW"kobold" III 1) and III 2) b),[2]He also acknowledgesCornelis Kilian[1574] dated earlier, though technically that was an etymological solution for "kabouter-manneken" derived fromcobalus/κόβαλος.[81]

- ^Glasenapp (1911),p. 132.

- ^Knapp 62.

- ^KKiliaan, Cornelis(1574)[81]cited by GrimmsDW"Kobold" III 3) b) c)

- ^Grimm (1878)DM3:129,Anmerkungen zu S. 377; Grimm (1888),Teut. Myth.4:1414

- ^Library of the Surgeon General's Office(1941)."Agricola".Index-catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon General's Office, United States Army (Army Medical Library)(4 ed.). U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 24–28.

- ^GrimmsDW"kobold", III. ursprung, nebenformen, 3) a) gives among theNebennamekobel,regarding it as a diminutive.[2]

- ^Grimms;Hildebrand, Rudolf(1868).Deutsches Wörterbuch,Band 5, s.v. "Kobalt"

- ^Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham(1898)."Cobalt".Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Giving the Derivation, Source, Or Origin of Common Phrases, Allusions, and Words that Have a Tale to Tell.Vol. 1 (new, revised, corrected, and enlarged ed.). London: Cassell. p. 267.

- ^abcdeBritten, Emma Hardinge(1884).Nineteenth century miracles, or, Spirits and their work in every country of the earth: a complete historical compendium of the great movement known as "modern spiritualism".New York: Published by William Britten: Lovell & Co. pp. 32–33.

- ^e.g.,Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable,[90]spiritualistEmma Hardinge Britten[91]

- ^On the three first days after our arrival, we only heard a few dull knocks, sounding in and about the mouth of the mine, as if produced by some vibrations or very distant blows... "[91]

- ^

We were about to sit down to tea when Mdlle. Gronin called our attention to the steady light, round, and about the size of a cheese plate, which appeared suddenly on the wall of the little garden directly opposite the door of the hut in which we sat.