Le génie du mal

| Le génie du mal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Guillaume Geefs |

| Year | 1848 |

| Type | white marble |

| Location | St. Paul's Cathedral,Liège |

Le génie du mal(orTheGeniusof EvilorThe Spirit of Evil), known informally in English asLuciferorThe Lucifer of Liège[1]is a religious sculpture executed in white marble and installed in 1848 by theBelgianartistGuillaume Geefs.Francophoneart historians often refer to the figure as anange déchu,a "fallen angel".

The sculpture is located in the elaboratepulpitofSt. Paul's Cathedral,Liège,and depicts a classically attractive man chained, seated, and nearlynudebut for drapery gathered over his thighs, his full length ensconced within amandorlaofbatwings. Geefs' work replaces an earlier sculpture created for the space by his younger brotherJoseph Geefs,L'ange du mal,which was removed from the cathedral because of its distracting allure and "unhealthy beauty".[2]

Two spirits, one site

[edit]Le génie du malis set within an opennicheformed at the base of twin ornate staircases carved withgothicfloralmotifs.[3]The curved railing of thesemi-spiral stairsreiterates the arc of the wings, which are retracted and cup the body. The versions by Guillaume and Joseph are strikingly similar at first glance and appear inspired by the samehuman model.For each, the fallen angel sits on a rock, sheltered by his folded wings; his uppertorso,arms, and legs are nude, his center-parted hairnape-length. The veined, membranous wings are articulated like a bat's, with a prominent thumb claw; the knobby, sinewyolecranoncombines bat and humananatomyto create an illusion ofrealism.[4]A brokensceptreand stripped-offcrownare held at the righthip.A tear runs from the angel's left eye. The white-marble sculpturesoccupy approximately the samedimensions,delimited by the space; Guillaume's measures 165 by 77 by 65 cm, or nearly five-and-a-half feet in height, with Joseph's only slightly larger at 168.5 by 86 by 65.5 cm.[5]

The commission

[edit]

In 1837, Guillaume Geefs was put in charge of designing the elaborate pulpit for St. Paul's, the theme of which was "the Triumph of Religion over the Genius of Evil". Geefs had come to prominence creatingmonumentalandpublic sculpturesin honor of political figures, expressing and capitalizing on thenationalistspirit that followedBelgian independence in 1830.Techniques ofrealismcoupled withNeoclassicalrestraint discipline any tendency towardRomantic heroismin these works, but Romanticism was to express itself more strongly in the Lucifer project.[6]

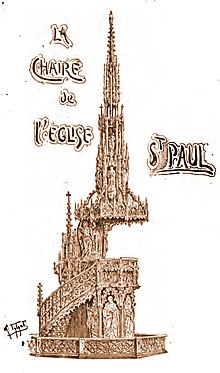

From the outset, sculpture was an integral part of Geefs' pulpit design, which featured representations of the saintsPeter,Paul,Hubertthe firstBishop of Liège,andLambert of Maastricht.A drawing of the pulpit by the Belgian illustratorMédard Tytgat,published in 1900, shows the front;Le génie du malwould be located at the base of the stairs on the opposite side, but the book in which the illustration appears omits mention of the work.[7]

The commission was originally awarded to Geefs' younger brother Joseph, who completedL'ange du malin 1842 and installed it the following year. It generated controversy at once and was criticized for not representing aChristianideal.[8]The cathedral administration declared that "this devil is too sublime."[9]The local press intimated that the work was distracting the "pretty penitent girls" who should have been listening to the sermons.[10]Bishop van Bommelsoon ordered the removal ofL'ange du mal,and the building committee passed the commission for the pulpit sculpture to Guillaume Geefs, whose version was installed at the cathedral permanently in 1848.[11]

Reception

[edit]Joseph exhibited his sculpture atAntwerpin 1843, along with four other works: a sculpture group calledThe Dream,and the individual statuesSt.Philomena,Faithful Love,andThe Fisherman's Orphan.[12]Known both asL'ange du mal(Angel of Evil) andLe génie du mal,the controversial piece was later received into the collections of theRoyal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium,where it has remained as of 2009.[13]

Joseph's work was admired at the highest levels of society.Charles Frederick,Grand DukeofSaxe-Weimar,ordered a marble replica as early as 1842.[14]The deracinated original was purchased for 3,000florinsbyWilliam II, King of the Netherlands,and was dispersed with the rest of his collection in 1850 following his death. In 1854, the artist sold aplaster castof the statue toBaron Bernard August von Lindenau,[15]the German statesman, astronomer, and art collector for whom theLindenau-Museum Altenburgis named.[16]The success of the work elevated Joseph Geefs to the top tier of sculptors in his day.[17]

L'ange du malis among six statues featured in a painting byPierre Langlet,The Sculpture Hall of the Brussels Museum(Salle de sculpture du Musée de Bruxelles,1882), along withLove and Maliceby another of the six Geefs sculptor-brothers, Jean.[18]It was not uniformly admired even as a work of art. When it appeared in an 1862 international exhibition, the reviewer criticized Geefs' work as "gentle and languid" and lacking in "muscle", "a devil sick...: the sting of Satan is taken out."[19]

'This devil is too sublime'

[edit]

Other than thevespertilionidwings, the fallen angel of Joseph Geefs[20]takes a completely human form, made manifest by itsartistic near-nudity.A languid scarf skims the groin, the hips are bared, and the open thighs form an avenue that leads to shadow.[21]The serpentine curve of waist and hip is given compositional play in relation to the wing-arcs. The torso is fit but youthful; smooth and graceful, almostandrogynous.The angel's expression has been described as "serious, somber, even fierce,"[22]and the cast-down gaze directs the viewer's eye along the body and thighs to the parted knees. The most obvious satanic element in addition to the wings is thesnakeuncoiling across the base of the rock.L'ange du malhas been called "one of the most disturbing works of its time."[23]

Joseph's sculptures are "striking for their perfect finish and grace, their elegant and even poetic line," but while exhibiting these qualities in abundance,L'ange du malis exceptional within the artist's body of work for its subject matter:[24]

It compellingly illustrates the Romantic era's attraction to darkness and the abyss, and the rehabilitation of the rebellious fallen angel. Thechiropteralwings, far from inspiring revulsion, form a frame that enhances the beauty of a youthful body.[25]

As a sort of "wingedAdonis",[26]the fallen angel can be seen as developing from Geefs' early nudeAdonis allant à la chasse avec son chien(Adonis Goes Hunting with His Hound).[27]The composition ofL'ange du malhas been compared to that ofJean-Jacques Feuchère's small bronzeSatan(1833),with Geefs' angel notably "less diabolic".[28]The humanizing of Lucifer through nudity is characteristic also of the Italian sculptorCostantino Corti's colossal work, executed a few years after the Geefs' versions. Corti depicts his Lucifer as frontally nude, though shielded discreetly by the pinnacle of rock he straddles, and framed with the feathered wings of his angel origin.[29]

Chained genius

[edit]

In contrast to Joseph's work, Guillaume'sgénieshows less flesh and is marked more strongly by sataniciconographyas neither human nor angelic. Whether Guillaume succeeded in removing the "seductive" elements may be a matter of individual perception.

Guillaume shifts the direction of the fallen angel's gaze so that it leads away from the body, with Lucifer's knees drawn together protectively. The drapery hangs from behind the right shoulder, pools on the right side, and undulates thickly over the thighs, concealing the hips, not quite covering the navel. At the same time, the flesh that remains exposed is resolutely modeled, particularly in the upper arms, pectorals, and calves, to reveal a more defined, muscled masculinity. The uplifted right arm allows the artist to explore the patterned tensions of theserratus anterior muscles,and the gesture and the angle of the head suggest that thegénieis warding off "divine chastisement".[30]

Symbols of Lucifer

[edit]Guillaume added several details to enhance the Luciferian iconography and the theme of punishment: at the angel's feet, the dropped "forbidden fruit",anapplewith bite marks, along with the broken-off tip of the sceptre, the stellarfinialof which marksLucifer as the Morning Star of classical tradition.Thenailsare narrow and elongated, like talons.[31]

A pair of horns may be intended to further dehumanize the figure, while introducing another note ofambiguity.Horns are animalistic markers of the satanic or demonic, but in a parallel tradition of religious iconography, "horns" represent points of light. Gods from antiquity who personify celestial phenomena such as the Sun or stars are crowned with rays, and some depictions ofMoses,the most famous being thesculptureofMichelangelo,are carved with "horns" similar to those of Geefs' Lucifer; seeHorns of Moses.

Promethean Lucifer

[edit]

But the most apparent departure fromL'ange du malis the placing of Lucifer inbondage,with his right ankle and left wrist chained. In 19th-century reinterpretations ofancient GreekandChristian myths,Lucifer was often cast as aPrometheanfigure, drawing on a tradition that the fallen angel was chained inHelljust as theTitanhad been chained andtorturedon the rock byZeus:"The samePrometheuswho is taken as ananalogueof thecrucified Christis regarded also as a type of Lucifer, "wroteHarold Bloomin remarks onMary Shelley's 19th-century classicFrankenstein,subtitledThe Modern Prometheus.[32]InA.H. Krappe'sfolklorictypology, Lucifer conforms to a type that includes Prometheus and the GermanicLoki.[33]

Guillaume Geefs' addition of fetters, with the swagged chain replacing the sneering serpent in Joseph's version, displays the angel's defeat in pious adherence to Christian ideology. At the same time, the titanic struggle of the tortured genius to free himself frommetaphoricalchains was a motif of Romanticism,[34]which took hold in Belgium in the wake of theRevolution of 1830.The Belgians had just secured their own "liberation"; over the ensuing two decades, there had been a craze for public sculpture, by the Geefs brothers and others, that celebrated the leaders of independence. The magnificently human figure of the iconic rebel who failed might have been expected to elicit a complex or ambivalent response.[35]The suffering face of thegénie,stripped of the angry hauteur ofL'ange du mal,has been read as expressing remorse and despair; a tear slips from the left eye.[36]

Sister of angels

[edit]In a 1990 essay, Belgian art historianJacques Van Lennepdiscussed how the conception ofLe génie du malwas influenced byAlfred de Vigny's long philosophical poemÉloa, ou La sœur des anges( "Eloa, or the Sister of Angels" ), published in 1824, which explored the possibility of Lucifer's redemption through love.[37]In this "lush and lyrical" narrative poem, Lucifer sets out to seduce the beautiful Eloa, an angel born from a tear shed byChristat the death ofLazarus.The Satanic lover is "literally a handsome devil, physically dashing, intellectually agile, irresistibly charismatic in speech and manner": in short, aRomantic hero."Since you are so beautiful," the naïve Eloa says, "you are no doubt good."

Lucifer declares that "I am he whom one loves and does not know,"[38]and says he weeps for the powerless and grants them the occasional reprieve of delight or oblivion. Despite Eloa's attempt to reconcile him with God, Lucifer cannot set aside his destructive pride. In the end, Eloa's love condemns her to Hell with Lucifer, and his triumph over her only brings him sadness.[39]

Himmelsweg

[edit]In 1986, the Belgian artistJacques CharliermadeLe génie du mala focal point of hisinstallationHimmelsweg( "Road to Heaven" ). A framed photograph of the sculpture hangs over a slender pedestal table that is draped with a black cloth. A transparent case on the table contains three books: aCarmelitestudy on the subject ofSatan,a scientific treatise onair,and a memorial of theBelgian Jewskilled atAuschwitz.On the lower shelf of the table areshackles.

Charlier has described his use ofLe génie du malas "a Romantic image that speaks to us ofseduction,evil,and thesinof forgetting. "The German title of the work refers to theNazieuphemism or "cold joke" for the access ramp that led to thegas chambers:"The Road to Paradise leads to Hell;the Fallis so close toredemption."[40]

References

[edit]- ^"Le génie du mal" could also be translated asEvil GeniusorEvil Spirit.Frenchgéniein this sense can overlap in meaning with its Englishcognate"genie".Geefs may have had in mind theKantian conception of genius,which influencedRomanticismin the 19th century.

- ^In French,beauté malsaine:Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium,Le génie du malby Joseph Geefs, Fabritius online cataloguedescription.Archived2011-07-16 at theWayback Machine[dead link]

- ^The sculpture may be viewed in its architectural settingonline,and at an angle showing thestained glasswindowsalso online.The view with stained glass windows is preserved also at theWebCitearchive.

- ^Soo Yang Geuzaine et Alexia Creusen, "Guillaume Geefs:Le Génie du Mal(1848) à la cathédrale Saint-Paul de Liège, "Vers la modernité. Le XIXesiècle au Pays de Liège,online catalogueof an exhibition presented by the University of Liège from 5 October 2001 to 20 January 2002.

- ^Michael Palmeret al.,500 chefs-d'oeuvre de l'art belge du XVesiècle à nos jours(Éditions Racine, n.d.), p. 203 [ online.]

- ^Geuzaine and Creusen,Vers la modernité;Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium,19th-century sculpture collectiononline introduction.Archived2009-03-22 at theWayback Machine

- ^Illustration byMédard Tytgatin Eloi Bartholeyns,Guillaume Geefs: sa vie et ses œuvres(Brussels: Schaerbeek, 1900), pp. 105 and 112.

- ^Ne rendant pas l'idée chrétienne:quoted by Vicky Chris,TrekLens.Archived2017-11-15 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Ce diable-là est trop sublime": originally quoted inL'Émancipation,4 August 1844, as cited byJacques Van Lennep,La Sculpture belge au xixe siècle, exposition organisée à Bruxelles du 5 octobre au 15 décembre 1990, La Générale de banque, Bruxelles(Exhibition catalogue, 1990); Geuzaine and Creusen,Vers la modernité.

- ^Edmond Marchal, "Étude sur la vie et les œuvres de Joseph-Charles Geefs,"Annuaire de l'Académie Royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique(Brussels, 1888), p. 316.

- ^Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, FabritiuscatalogueArchived2011-07-16 at theWayback Machine,from Francisca Vandepitte,Le Romantisme en Belgique. Entre réalités, rêves et souvenirs (exposition): Bruxelles, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique; Espace Culturel ING; Musée Antoine Wiertz, 18.03–31.07.2005(Brussels, 2005), p. 109.

- ^Marchal,Annuairep. 315.

- ^Joseph's work is often referred to asL'ange du mal,but its formal title according to the Royal Museums' online 19th-century sculpturecatalogueArchived2009-03-22 at theWayback MachineremainsLe génie du mal.The common titleL'ange du malis used in this article to distinguish Joseph's sculpture from that of Guillaume.

- ^As of 2009, this copy remains in the collections of theGoetheGoethe-Nationalmuseum,Weimar.

- ^Royal Museums, Fabritius description; Edmond Marchal,La sculpture et les chefs-d'œuvre de l'orfèvrerie belges(Brussels, 1895), p. 684online;Michael Palmeret al.,500 chefs-d'oeuvre de l'art belge du XVesiècle à nos jours(Éditions Racine, n.d.), p. 203online.

- ^"Das Lindenau-Museum Altenburg"(in German). Archived fromthe originalon April 20, 2009.

- ^"Une légtimate admiration accueillit cette œuvre. Le plus grand succès répondit à l'attente de l'artiste et plaça celui-ci au premier rang des statuaires de ce temps": Marchal,Annuairep. 315.

- ^Françoise Roberts-Jones-Popelier,Chronique d'un musée: Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelles(Pierre Mardaga, 1987), p. 31online,with the painting reproduced on p. 32.Love and Maliceby Jean Geefs may be viewedonline.Archived2011-07-16 at theWayback Machine

- ^J. Beavington Atkinson, "Modern Sculpture of All Nations in the Exhibition,"The Art Journal Illustrated Catalogue of the International Exhibition 1862p. 318.

- ^In Dutch and German sources, the artist's name may appear as Jozef Geefs.

- ^For better angles on the compositional treatment of the drapery in relation to the groin, see500 chefsanddetail.More information available on the photodetail.

- ^500 chefs-d'oeuvre de l'art belgep. 203. The angel's facial expression may not be apparent in the photograph that illustrates this article; viewanother angle.

- ^Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, 19th-century sculpture collectiononline introduction.Archived2009-06-24 at theWayback Machine

- ^500 chefs-d'oeuvre de l'art belgep. 203.

- ^"Elle illustre en effet l'attrait de l'époque romantique pour les ténèbres, l'abîme, et sa réhabilitation de l'ange rebelle déchu. Les ailes de chéiroptère loin d'inspirer la révulsion, forme un écrin mettant en valeur la beauté d' un corps juvénile": Vicky Chris,TrekLensArchived2017-11-15 at theWayback Machine,with a side view of the photo showing the exposure of the hip.

- ^Royal Museums of Fine Arts, FabritiusLe génie du mal.Archived2011-07-16 at theWayback Machine

- ^Royal Museums of Fine Arts, FabritiusAdonis allant à la chasse.Archived2011-07-16 at theWayback Machine

- ^Didier Rykner, review of the exhibition "Le romantisme en Belgique. Entre réalités, rêves et souvenirs," 18 March–31 July 2005 at theRoyal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium,Brussels, and Espace Culturel ING,La Tribune de l'Art,13 April 2005online.Archived2009-11-28 at theWayback MachineFeuchère'sSatanexists in multiple copies. The 1833 original ofSatanheld by theLouvreis not on public display, but may be viewedonline.As of 30 April 2009, an 1836 version was on public display at theLos Angeles County Museum of Art;it may be viewed among the museum'sonline collections.Archived2011-06-04 at theWayback MachineFor the version at the Royal Museum in Brussels, search Feuchère in the museum'sdatabase.Archived2009-03-23 at theWayback Machine

- ^See article onCostantino Cortifor an engraving ofLucifer.

- ^Geuzaine and Creusen,Vers la modernité.

- ^Geuzaine and Creusen,Vers la modernité.

- ^Harold Bloom,1965 afterword republished in the Signet Classic 2000 edition ofMary Shelley'sFrankenstein,p. 201online.The literature on the connection between Lucifer and Prometheus made in 19th-century art and literature is vast. See, for instance, discussion ofGoetheand theGnosticLucifer in Steven M. Wasserstrom,Religion after Religion: Gershom Scholem, Mircea Eliade, and Henry Corbin at Eranos(Princeton University Press, 1999), p. 210ff.online.Discussion of Lucifer inStrindberg'sCoram Populoin Harry Gilbert Carlson,Out of Inferno: Strindberg's Reawakening as an Artist(University of Washington Press, 1996), pp. 103–106online.The association of Lucifer withPrometheusand other mythological figures such asLokiwas a particular feature of 19th-centurytheosophyand the esoteric writings ofH.P. Blavatsky;seeThe Secret Doctrine(London, 1893), vol. 2, p. 296online.The Promethean qualities of Lucifer are a standard theme inMiltonstudies; seeLucifer and Prometheusfor a perspective onParadise Lost.

- ^Lois Bragg,Oedipus Borealis: The Aberrant Body in Old Icelandic Myth and Saga(Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004), pp. 132–133, particularly point 7online.

- ^Pam Morris,Realism(Routledge, 2003), p. 52online.

- ^Royal Museum of Fine Arts,"Romanticism."Archived2009-06-24 at theWayback Machine

- ^Geuzine and Creusen,Vers la modernité.

- ^Jacques Van LennepArchived2009-05-31 at theWayback Machine,La Sculpture belge au xixe siècle, exposition organisée à Bruxelles du 5 octobre au 15 décembre 1990, La Générale de banque, Bruxelles(Exhibition catalogue, 1990), as cited by Geuzaine and Creusen,Vers la modernité.Although in origin Lucifer and Satan may be distinct beings,Eloadraws on a literary tradition thatconflatesthe two figures.

- ^In French,Je suis celui qu'on aime et qu'on ne connaît pas.

- ^Elizabeth Cheresh Allen,A Fallen Idol Is Still a God:Lermontovand the Quandaries of Cultural Transition(Stanford University Press, 2007), pp. 89–90online;Miriam Van Scott,The Encyclopedia of Hell(Macmillan, 1999), p. 103online.

- ^Nadja Vilenne galerie,HimmelswegArchived2008-07-04 at theWayback Machine,with artist interview conducted by R.Vandersanden; gallery news blogged by Jean-Michel Botquin, EnglishversionArchived2008-07-04 at theWayback Machine,13 March 2008. On the wordHimmelwegorHimmelsweg,see Carrie Supple,From Prejudice to Genocide: Learning about the Holocaust(Trentham Books, 1993, 2nd ed.), p. 167online;Kate Millett,The Politics of Cruelty: An Essay on the Literature of Political Imprisonment(W.W. Norton, 1995), p. 59online;see also "The Cold Joke and Desecration" inJonathan Glover,Humanity: A Moral History of the Twentieth Century(Yale University Press, 2000), p. 341M1 online.

Selected bibliography

[edit]- Soo Yang Geuzaine et Alexia Creusen, "Guillaume Geefs:Le Génie du Mal(1848) à la cathédrale Saint-Paul de Liège, "Vers la modernité. Le XIXe siècle au Pays de Liège,exhibition presented by the University of Liège, 5 October 2001 to 20 January 2002online catalogue.

- Michael Palmeret al.,500 chefs-d'oeuvre de l'art belge du XVesiècle à nos jours(Éditions Racine, n.d.), p. 203online.

- Edmond Marchal, "Étude sur la vie et les œuvres de Joseph-Charles Geefs,"Annuaire de l'Académie Royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique(Brussels, 1888).

- Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium,Le génie du malby Joseph Geefs, Fabritiusonline catalogue.

External links

[edit]- Guillaume Geefs'Le génie du malmay be viewed online in itsarchitectural context;also angle showing thestained glass

- Joseph Geefs,L'ange du mal(asLe génie du mal)full view;hands detail;side view

- Himmelsweginstallation of Jacques Charlier,Nadja Vilenne galerie