Leading tone

Inmusic theory,aleading tone(also calledsubsemitoneorleading notein the UK) is anoteorpitchwhichresolvesor "leads" to a note onesemitonehigher or lower, being a lower and upper leading tone, respectively. Typically,theleading tone refers to the seventhscale degreeof amajor scale(![]() ), amajor seventhabove thetonic.In themovable do solfègesystem, the leading tone is sung assi.

), amajor seventhabove thetonic.In themovable do solfègesystem, the leading tone is sung assi.

A leading-tone triad is atriadbuilt on the seventh scale degree in a major key (viioinRoman numeral analysis), while a leading-tone seventh chord is aseventh chordbuilt on the seventh scale degree (viiø7).Walter Pistonconsiders and notates viioas V0

7,an incompletedominant seventh chord.[1](For the Roman numeral notation of these chords, seeRoman numeral analysis.)

Note

[edit]Seventh scale degree (or lower leading tone)

[edit]Typically, when people speak oftheleading tone, they mean the seventh scale degree (![]() ) of the major scale, which has a strong affinity for and leads melodically to thetonic.[2]It is sung assiinmovable-do solfège.For example, in the F major scale, the leading note is the note E.

) of the major scale, which has a strong affinity for and leads melodically to thetonic.[2]It is sung assiinmovable-do solfège.For example, in the F major scale, the leading note is the note E.

As adiatonic function,the leading tone is the seventh scale degree of anydiatonic scalewhen the distance between it and the tonic is a singlesemitone.In diatonic scales in which there is awhole tonebetween the seventh scale degree and the tonic, such as theMixolydian mode,the seventh degree is called thesubtonic.However, in modes without a leading tone, such asDorianand Mixolydian, a raised seventh is often featured during cadences,[3]such as in theharmonic minor scale.

A leading tone outside of the current scale is called asecondaryleading tone,leading to asecondary tonic.It functions to brieflytonicizea scale tone (usually the 5th degree)[4]as part of asecondary dominantchord. In the second measure ofBeethoven'sWaldstein Sonata(shown below), the F♯'s function as secondary leading tones, which resolve to G in the next measure.[4]

Descending, or upper, leading tone

[edit]

By contrast, a descending, or upper, leading tone[5][6]is a leading tone that resolvesdown,as opposed to the seventh scale degree (alowerleading tone) which resolves up. The descending, or upper, leading tone usually is a lowered second degree (♭![]() ) resolving to the tonic, but the expression may at times refer to a♭

) resolving to the tonic, but the expression may at times refer to a♭![]() resolving to the dominant.[citation needed]In German, the termGegenleitton( "counter leading tone" ) is used byHugo Riemannto denote the descending or upper leading-tone (♭

resolving to the dominant.[citation needed]In German, the termGegenleitton( "counter leading tone" ) is used byHugo Riemannto denote the descending or upper leading-tone (♭![]() ),[7]butHeinrich Schenkerusesabwärtssteigenden Leitton[8]( "descending leading tone" ) to mean the descending diatonicsupertonic(♮

),[7]butHeinrich Schenkerusesabwärtssteigenden Leitton[8]( "descending leading tone" ) to mean the descending diatonicsupertonic(♮![]() ).)

).)

Thetritone substitution,chord progression ii–subV–I on C (Dm–Db7–C), results in an upper leading note.

Analysis

[edit]According toErnst Kurth,[9]themajorandminor thirdscontain "latent" tendencies towards theperfect fourthand whole tone, respectively, and thus establishtonality.However,Carl Dahlhaus[10]contests Kurth's position, holding that this drive is in fact created through or with harmonic function, a root progression in another voice by a whole tone or fifth, or melodically (monophonically) by the context of the scale. For example, the leading tone of alternating C chord and F minor chords is either the note E leading to F (if F is tonic), or A♭leading to G (if C is tonic).

In works from the 14th- and 15th-century Western tradition, the leading tone is created by the progression from imperfect to perfect consonances, such as a major third to a perfect fifth or minor third to a unison.[citation needed]The same pitch outside of the imperfect consonance is not a leading tone.

Forte claims that the leading tone is only one example of a more general tendency: the strongest progressions, melodic and harmonic, are byhalf step.[11]He suggests that one play a G major scale and stop on the seventh note (F♯) to personally experience the feeling of lack caused by the "particularly strong attraction" of the seventh note to the eighth (F♯→G'), thus its name.

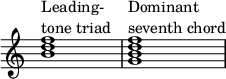

Leading-tone triad

[edit]A leading-tone chord is a triad built on the seventh scale degree in major and the raised seventh-scale-degree in minor. The quality of the leading-tone triad isdiminishedin both major and minor keys.[12]For example, in both C major and C minor, it is a B diminished triad (though it is usually written infirst inversion,as described below).

According to John Bunyan Herbert, (who uses the term "subtonic",which later came to usually refer to a seventh scale degree pitched a whole tone below the tonic note),

The subtonic [leading-tone] chord is founded upon seven (the leading tone) of the major key, and is a diminished chord... The subtonic chord is very much neglected by many composers, and possibly a little overworked by others. Its occasional use gives character and dignity to a composition. On the whole, the chord has a poor reputation. Its history, in brief, seems to be: Much abused and little used.[13]

Function

[edit]The leading-tone triad is used in several functions. It is commonly used as apassing chordbetween aroot positiontonic triad and a first inversion tonic triad:[14]that is, "In addition to its basic function of passing between I and I6,VII6has another important function: it can form a neighboring chord to I or I6."[15]In that instance, the leading-tone triad prolongs tonic through neighbor and passing motion. The example below shows two measures from the fourth movement ofBeethoven'sPiano Sonata No. 3 in C major, Op. 2[16]in which a leading-tone triad functions as a passing chord between I and I6.

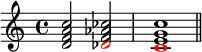

The leading-tone triad may also be regarded as an incompletedominant seventh chord:"A chord is called 'Incomplete' when its root is omitted. This omission occurs, occasionally, in the chord of the dom.-seventh, and the result is a triad upon the leading tone."[17]

Some sources say the chord is not a chord; some argue it is an incomplete dominant seventh chord, especially when the diminished triad is written in its first inversion (resembling asecond inversiondominant seventh without a root):[13]

The subtonic [i.e. leading-tone] chord is a very common chord and a useful one. The triad differs in formation from the preceding six [major and minor diatonic] triads. It is dissonant and active... a diminished triad. The subtonic chord belongs to the dominant family. The factors of the triad are the same tones as the three upper factors of the dominant seventh chord and progress in the same manner. These facts have led many theorists to call this triad a 'dominant seventh chord without root.'... The subtonic chord in both modes has suffered much criticism from theorists although it has been and is being used by masters. It is criticized as being 'overworked', and that much can be accomplished with it with a minimum of technique.[18]

For example, viio6often substitutes for V4

3,which it closely resembles, and its use may be required in situations byvoice leading:"In a strict four-voice texture, if the bass is doubled by the soprano, the VII6[viio6] is required as a substitute for the V4

3".[19]

Voice leading

[edit]Since the leading-tone triad is a diminished triad, it is usually found in itsfirst inversion:[20][21]According to Carl Edward Gardner, "The first inversion of the triad is considered, by many, preferable toroot position.The second inversion of the triad is unusual. Some theorists forbid its use. "[22]

In afour-part chorale texture,the third of the leading-tone triad isdoubledin order to avoid adding emphasis on thetritonecreated by the root and the fifth. Unlike a dominant chord where the leading tone can be frustrated and not resolve to the tonic if it is in an inner voice, the leading tone in a leading-tone triad must resolve to the tonic. Commonly, the fifth of the triad resolves down since it is phenomenologically similar to the seventh in adominant seventh chord.All in all, the tritone resolvesinwardif it is written as adiminished fifth(m. 1 below) andoutwardif it is written as anaugmented fourth(m. 2).

Leading-tone seventh chord

[edit]

The leading-tone seventh chords are viiø7and viio7,[24]thehalf-diminishedanddiminished seventh chordson the seventh scale degree (![]() ) of the major andharmonic minor.For example, in C major and C minor, the leading-tone seventh chords are B half-diminished (B–D–F–A) and B diminished (B–D–F–A♭), respectively.

) of the major andharmonic minor.For example, in C major and C minor, the leading-tone seventh chords are B half-diminished (B–D–F–A) and B diminished (B–D–F–A♭), respectively.

Leading-tone seventh chords were not characteristic of Renaissance music but are typical of the Baroque and Classical period. They are used more freely in Romantic music but began to be used less in classical music as conventions of tonality broke down. They are integral to ragtime and contemporary popular and jazz music genres.[25]

Composers throughout thecommon practice periodoften employedmodal mixturewhen using the leading-tone seventh chord in a major key, allowing for the substitution of the half-diminished seventh chord with the fully diminished seventh chord (by lowering its seventh). This mixture is commonly used when the leading-tone seventh chord is functioning as asecondary leading-tone chord.

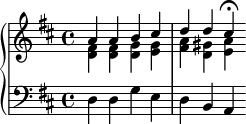

The example below shows fully diminished seventh chords in the key of D major in the right hand in the third movement ofMozart'sPiano Sonata No. 5in G major.[26]

Function

[edit]The leading-tone seventh chord has adominantfunctionand may be used in place of V or V7.[27]Just as viiois sometimes considered an incomplete dominant seventh chord, a leading-tone seventh chord is often considered a "dominant ninth chordwithout root ".[28][20])

For variety, leading-tone seventh chords are frequentlysubstitutedfordominant chords,with which they have three common tones:[23]"The seventh chord founded upon the subtonic [in major]... is occasionally used. It resolves directly to the tonic... This chord may be employed without preparation."[29]

Voice leading

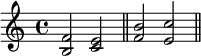

[edit]In contrast to leading-tone triads, leading-tone seventh chords appear inroot position.The example below shows leading-tone seventh chords (in root position) functioning as dominants in areductionof Mozart'sDon Giovanni,K. 527, act 1, scene 13.[30]

François-Joseph Fétistunes the leading-tone seventh in major 5:6:7:9.[31]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Goldman 1965,17.

- ^Benward and Saker 2003,203.

- ^Benward and Saker 2009,4.

- ^abBerry 1987,55.

- ^abBerger 1987,148.

- ^Coker 1991,50.

- ^Riemann 1918,113–114.

- ^Schenker 1910,pp. 143–145.

- ^Kurth 1913,119–736.

- ^Dahlhaus 1990,44–47.

- ^Forte 1979,11–2.

- ^Benjamin, Horvit & Nelson 2008,106.

- ^abHerbert 1897,102.

- ^abForte 1979,122.

- ^Aldwell, Schachter, and Cadwallader 2010,138.

- ^Forte 1979,169.

- ^Goetschius 1917,72, §162–163, 165.

- ^Gardner 1918,48, 50.

- ^Forte 1979,168.

- ^abGoldman 1965,72.

- ^Root 1872,315.

- ^Gardner 1918,48–49.

- ^abBenward and Saker 2003,217.

- ^Benward and Saker 2003,218–219.

- ^Benward and Saker 2003,220–222.

- ^Benward and Saker 2003,218.

- ^Benjamin, Horvit & Nelson 2008,128.

- ^Gardner 1918,49.

- ^Herbert 1897,135.

- ^Benward and Saker 2003,219.

- ^Fétis & Arlin 1994,139n9.

Sources

- Aldwell, Edward,Carl Schachter,and Allen Cadwallader (2010).Harmony and Voice-Leading,fourth edition. New York: Schirmer/Cengage Learning.ISBN978-0-495-18975-6

- Benjamin, Thomas; Horvit, Michael; and Nelson, Robert (2008).Techniques and Materials of Music.7th edition. Thomson Schirmer.ISBN978-0-495-18977-0.

- Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003).Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I,seventh edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0-07-294262-0.

- Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2009).Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. II,Eighth edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0-07-310188-0.

- Berger, Karol(1987).Musica Ficta: Theories of Accidental Inflections in Vocal Polyphony from Marchetto da Padova to Gioseffo Zarlino.Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-32871-3(cloth);ISBN0-521-54338-X(pbk).

- Berry, Wallace (1976/1987).Structural Functions in Music.Dover.ISBN0-486-25384-8.

- Coker, Jerry(1991).Elements of the Jazz Language for the Developing Improvisor.Miami, Florida: CCP/Belwin.ISBN1-57623-875-X.

- Dahlhaus, Carl(1990).Studies on the Origin of Harmonic Tonality,trans. Robert O. Gjerdingen. Princeton: Princeton University Press.ISBN0-691-09135-8.

- Fétis, François-Josephand Arlin, Mary I. (1994).Esquisse de l'histoire de l'harmonie.ISBN978-0-945193-51-7.

- Forte, Allen(1979).Tonal Harmony.Third edition. Holt, Rinhart, and Winston.ISBN0-03-020756-8.

- Gardner, Carl Edward (1918).Music Composition: A New Method of Harmony.Carl Fischer. [ISBN unspecified].

- Goetschius, Percy(1917).The Theory and Practice of Tone-Relations: An Elementary Course of Harmony,21st edition. New York: G. Schirmer.

- Goldman, Richard Franko(1965).Harmony in Western Music.Barrie & Jenkins/W. W. Norton.ISBN0-214-66680-8.

- Herbert, John Bunyan (1897).Herbert's Harmony and Composition.Fillmore Music.

- Kurth, Ernst(1913).Die Voraussetzungen der theoretischen Harmonik und der tonalen Darstellungssysteme.Bern: Akademische Buchhandlung M. Drechsel. Unaltered reprint edition, with an afterword by Carl DahlhausMunich: E. Katzbichler, 1973.ISBN3-87397-014-7.

- Riemann, Hugo.Handbuch der Harmonie und Modulationslehre,Berlin, Max Hesses, 6th edition, 1918

- Root, George Frederick(1872).The Normal Musical Hand-book.J. Church. [ISBN unspecified].

- Schenker, Heinrich(1910).Kontrapunkt(in German). Vol. I. Vienna:Universal Edition.

- Schenker, Heinrich (1987).Counterpoint.Vol. I. Translated by John Rothgeb; Jürgen Thym. New York: Schirmer.ISBN9780028732206.

Further reading

[edit]- Kostka, Stefan;Payne, Dorothy (2004).Tonal Harmony(5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.ISBN0-07-285260-7.OCLC51613969.

- Schenker, Heinrich.Free Composition,Ernst Oster transl., New York, Longman, 1979

- Stainer, John,and William Alexander Barrett (eds.) (1876).A Dictionary of Musical Terms.London: Novello, Ewer and Co. New and revised edition, London: Novello & Co, 1898.

![{

#(set-global-staff-size 18)

{ \new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative c {

\once\override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #4

\clef bass \time 4/4

\tempo "Allegro con brio" 4 = 176

\override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #2.5

r8\pp <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e>

<c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> <c e> <d fis> <d fis>

<d g>4.( b'16 a) g8 r r4

\clef treble \grace { cis''8( } d4~)( d16 c b a g4-.) r4

}

>>

\new Staff { \relative c, {

\clef bass

c8 <c g'> <c g'> <c g'> <c g'> <c g'> <c g'> <c g'>

<c g'> <c g'> <c g'> <c g'> <c g'> <c g'> <c a'> <c a'>

<b g'> <b g'> <b g'> <b g'> <b g'> <b g'> <b g'> <b g'>

<b g'> <b g'> <b g'> <b g'> <b g'>[ <b g'> <b g'> <b g'>]

} }

>> } }](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/k/ikv1pfpwwh1sdhp2m5cyizf603i6mmc/ikv1pfpw.png)

![\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\relative c' {

\clef treble \key g \major \time 3/8

\set Score.currentBarNumber = #64

\bar ""

<e e'>8 e'16[ dis fis e]

\once \override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #3.5 g16([\p e cis bes)] \once \override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #3.5 a8\f

g'16([ e cis bes)] \once \override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #3.5 a8\f

g'16([ e cis bes)] \once \override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #3.5 a8\f

g'16([ e cis bes)] \once \override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #3.5 a8\f

r r <d fis a>\f

}

>>

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative c' {

\clef bass \key g \major \time 3/8

R4.

r8 r \clef treble <cis e g>

r8 r <cis e g>

r8 r <cis e g>

r8 r <cis e g>

\clef bass \once \override DynamicLineSpanner.staff-padding = #3.5 d,16([^\p fis a d)] fis8

}

>>

>>](https://upload.wikimedia.org/score/r/8/r80zzk8k1cf9j4isv5iqnbao6yv86vh/r80zzk8k.png)