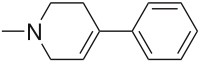

MPTP

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.044.475 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine |

PubChemCID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard(EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H15N | |

| Molar mass | 173.259g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 40 °C (104 °F; 313 K)[2] |

| Boiling point | 128 to 132 °C (262 to 270 °F; 401 to 405 K) 12 Torr[1] |

| Slightly soluble | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704(fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in theirstandard state(at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

MPTP(1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) is anorganic compound.It is classified as atetrahydropyridine.It is of interest as aprecursorto theneurotoxinMPP+,which causes permanent symptoms ofParkinson's diseaseby destroying dopaminergicneuronsin thesubstantia nigraof thebrain.It has been used to study disease models in various animals.[3][4]

While MPTP itself has nopsychoactiveeffects, the compound may be accidentally produced during the manufacture ofMPPP,a synthetic opioiddrugwith effects similar to those ofmorphineandpethidine(meperidine). The Parkinson-inducing effects of MPTP were first discovered following accidental injection as a result of contaminated MPPP.

Toxicity[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(December 2022) |

Injection of MPTP causes rapid onset ofParkinsonism,hence users of MPPP contaminated with MPTP will develop these symptoms.

MPTP itself is not toxic, but it is alipophiliccompound and can therefore cross theblood–brain barrier.Once inside the brain, MPTP is metabolized into the toxiccation1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium(MPP+)[5]by the enzymemonoamine oxidase B(MAO-B) ofglial cells,specifically astrocytes. MPP+kills primarilydopamine-producingneuronsin a part of the brain called thepars compactaof thesubstantia nigra.MPP+interferes withcomplex Iof theelectron transport chain,a component ofmitochondrialmetabolism, which leads to cell death and causes the buildup offree radicals,toxic molecules that contribute further to cell destruction.

Because MPTP itself is not directly harmful, toxic effects of acute MPTP poisoning can be mitigated by the administration ofmonoamine oxidase inhibitors(MAOIs) such asselegiline.MAOIs prevent the metabolism of MPTP to MPP+by inhibiting the action of MAO-B, minimizing toxicity, and preventing neural death.

Dopaminergic neurons are selectively vulnerable to MPP+because DA neurons exhibit dopaminereuptakewhich is mediated by DAT, which also has high-affinity for MPP+.[6]Thedopamine transporterscavenges for excessive dopamine at the synaptic spaces and transports them back into the cell. Even though this property is exhibited by both VTA and SNc neurons, VTA neurons are protective against MPP+insult due to the expression of calbindin. Calbindin regulates the availability of Ca2+ within the cell, which is not the case in SNc neurons due to their high-calcium-dependent autonomous pacemaker activity.

The gross depletion of dopaminergic neurons severely affectscorticalcontrol of complex movements. The direction of complex movement is based from the substantia nigra to theputamenandcaudate nucleus,which then relay signals to the rest of the brain. This pathway is controlled via dopamine-using neurons, which MPTP selectively destroys, resulting, over time, in parkinsonism.

MPTP causes Parkinsonism inprimates,including humans.Rodentsare much less susceptible. Rats are almost immune to the adverse effects of MPTP. Mice were thought to only suffer from cell death in the substantia nigra (to a differing degree according to the strain of mice used) but do not show Parkinsonian symptoms;[7]however, most of the recent studies indicate that MPTP can result in Parkinsonism-like syndromes in mice (especially chronic syndromes).[8][9]It is believed that the lower levels of MAO-B in the rodent brain's capillaries may be responsible for this.[7]

Discovery in users of illicit drugs[edit]

The neurotoxicity of MPTP was hinted at in 1976 after Barry Kidston, a 23-year-old chemistry graduate student inMaryland,US, synthesized MPPP with MPTP as a major impurity and self-injected the result. Within three days he began exhibiting symptoms of Parkinson's disease. TheNational Institute of Mental Healthfound traces of MPTP and otherpethidineanalogsin his lab. They tested the substances on rats, but due to rodents' tolerance for this type of neurotoxin, nothing was observed. Kidston's Parkinsonism was treated withlevodopabut he died 18 months later from acocaineoverdose. Upon autopsy,Lewy bodiesand destruction of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra were discovered.[10][11]

In 1983, four people inSanta Clara County, California,US, were diagnosed with Parkinsonism after having used MPPP contaminated with MPTP, and as many as 120 were reported to have been diagnosed with Parkinson's symptoms.[12]The neurologistJ. William Langstonin collaboration with NIH tracked down MPTP as the cause, and its effects on primates were researched. After performing neural grafts of fetal tissue on three of the patients atLund University HospitalinSweden,the motor symptoms of two of the three patients were successfully treated, and the third showed partial recovery.[13][14]

Langston documented the case in his 1995 bookThe Case of the Frozen Addicts,[15]which was later featured in twoNOVAproductions byPBS,re-aired in the UK on theBBCscience seriesHorizon.[16]

Contribution of MPTP to research into Parkinson's disease[edit]

Langstonet al.(1984) found that injections of MPTP insquirrel monkeysresulted in Parkinsonism, symptoms of which were subsequently reduced bylevodopa,the drug-of-choice in the treatment of Parkinson's disease along withcarbidopaandentacapone.The symptoms and brain structures of MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease are fairly indistinguishable to the point that MPTP may be used to simulate the disease in order to study Parkinson's disease physiology and possible treatments within the laboratory. Mouse studies have shown that susceptibility to MPTP increases with age.[17]

Knowledge of MPTP and its use in reliably recreating Parkinson's disease symptoms in experimental models has inspired scientists to investigate the possibilities of surgically replacing neuron loss through fetal tissue implants,subthalamicelectrical stimulationandstem cellresearch, all of which have demonstrated initial provisional successes.

It has been postulated that Parkinson's disease may be caused by minute amounts of MPP+-like compounds from ingestion or exogenously through repeated exposure and that these substances are too minute to be detected significantly by epidemiological studies.[18]

In 2000, another animal model for Parkinson's disease was found. It was shown that thepesticideandinsecticiderotenonecauses Parkinsonism in rats by killing dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Like MPP+,rotenone also interferes withcomplex Iof theelectron transport chain.[19]

Synthesis and uses[edit]

MPTP was first synthesized as a potentialanalgesicin 1947 by Zieringet al.by reaction ofphenylmagnesium bromidewith1-methyl-4-piperidinone.[20]It was tested as a treatment for various conditions, but the tests were halted when Parkinson-like symptoms were noticed in monkeys. In one test of the substance, two of six human subjects died.[21]

MPTP is used in industry as a chemical intermediate; thechlorideof the toxic metabolite MPP+,cyperquat,has been used as aherbicide.[21]While cyperquat is not used anymore, the closely related substanceparaquatis still being used as a herbicide in some countries.

In popular culture[edit]

- In the novelNeuromancer,authored byWilliam Gibson,MPTP is used as a means of inducing Parkinsonism in another character.

- MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease is featured in theLaw & Orderepisode "Stiff."

- In Roger Williams' novelThe Metamorphosis of Prime Intellectthe protagonist administers MPTP to the anti-heroine’s former nurse, who had stolen her painkillers in life, doing so as a means of neurodegenerative torture.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Buchi, I. J. (1952). "Synthese und analgetische Wirkung einiger 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-piperidin-(4)-alkylsulfone. 1. Mitteilung".Helvetica Chimica Acta.35(5): 1527–1536.doi:10.1002/hlca.19520350514.

- ^"1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine".ChemIDplus.

- ^Duty, Susan; Jenner, Peter (2011)."Animal models of Parkinson's disease: A source of novel treatments and clues to the cause of the disease".British Journal of Pharmacology.164(4): 1357–1391.doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01426.x.PMC3229766.PMID21486284.

- ^Narmashiri, Abdolvahed; Abbaszadeh, Mojtaba; Ghazizadeh, Ali (2022). "The effects of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) on the cognitive and motor functions in rodents: A systematic review and meta-analysis".Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.140:104792.doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104792.PMID35872230.S2CID250929452.

- ^Frim, D. M.; Uhler, T. A.; Galpern, W. R.; Beal, M. F.; Breakefield, X. O.; Isacson, O. (1994)."Implanted fibroblasts genetically engineered to produce brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevent 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium toxicity to dopaminergic neurons in the rat".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.91(11): 5104–5108.Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.5104F.doi:10.1073/pnas.91.11.5104.PMC43940.PMID8197193.

- ^Richardson, Jason (2005)."Richardson, Jason R., et al." Paraquat neurotoxicity is distinct from that of MPTP and rotenone ".Toxicological Sciences.88(1): 193–201.doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfi304.PMID16141438.

- ^abLangston, J. W. (2002)."Chapter 30 The Impact of MPTP on Parkinson's Disease Research: Past, Present, and Future".In Factor, S. A.; Weiner, W. J. (eds.).Parkinson's Disease. Diagnosis and Clinical Management.Demos Medical Publishing.

- ^"Parkinson's Disease Models"(PDF).Neuro Detective International.Retrieved2012-03-06.

- ^Luo Qin; Peng Guoguang; Wang Jiacai; Wang Shaojun (2010)."The Establishment of Chronic Parkinson's Disease in Mouse Model Induced by MPTP".Journal of Chongqing Medical University.2010(8): 1149–1151.Retrieved2012-03-06.

- ^Fahn, S. (1996). "Book Review -- The Case of the Frozen Addicts: How the Solution of an Extraordinary Medical Mystery Spawned a Revolution in the Understanding and Treatment of Parkinson's Disease".The New England Journal of Medicine.335(26): 2002–2003.doi:10.1056/NEJM199612263352618.

- ^Davis GC, Williams AC, Markey SP, Ebert MH, Caine ED, Reichert CM, Kopin IJ (1979). "Chronic parkinsonism secondary to intravenous injection of meperidine analogs".Psychiatry Research.1(3): 249–254.doi:10.1016/0165-1781(79)90006-4.PMID298352.S2CID44304872.

- ^"Bogus Heroin Brings Illness on the Coast".The New York Times.9 December 1983.Retrieved3 September2023.

- ^"Success reported using fetal tissue to repair a brain".The New York Times.26 November 1992.

- ^"How tainted drugs" froze "young people—but kickstarted Parkinson's research".Ars Technica.Retrieved21 May2016.

- ^Langston, J. W.;Palfreman, J.(May 1995).The Case of the Frozen Addicts.Pantheon Books.ISBN978-0-679-42465-9.

- ^"The Case of the Frozen Addicts" first broadcast 7 April 1986 and "Awakening the Frozen Addicts" first broadcast 4 January 1993. SeeList of Horizon episodes

- ^Jackson-Lewis, V.; Przedborski, S. (2007). "Protocol for the MPTP Mouse Model of Parkinson's Disease".Nature Protocols.2(1): 141–151.doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.342.PMID17401348.S2CID39743261.

- ^"Pesticides and Parkinson's Disease - A Critical Review"(PDF).Institute of Environment and Health,Cranfield University.October 2005. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on February 27, 2008.

- ^"Summary of the Article by Dr. Greenamyre on Pesticides and Parkinson's Disease".National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 9 February 2005. Archived fromthe originalon October 16, 2007.

- ^Lee, J.; Ziering, A.; Heineman, S. D.; Berger, L. (1947). "Piperidine Derivatives. Part II. 2-Phenyl- and 2-Phenylalkyl-Piperidines".Journal of Organic Chemistry.12(6): 885–893.doi:10.1021/jo01170a021.PMID18919741.

- ^abVinken, P. J.; Bruyn, G. W. (1994).Intoxications of the Nervous System.Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 369.ISBN978-0-444-81284-1.

External links[edit]

- Langston, J. William; Ballard, Philip; Tetrud, James W.; Irwin, Ian (25 February 1983). "Chronic Parkinsonism in Humans Due to a Product of Meperidine-Analog Synthesis".Science.219(4587): 979–980.Bibcode:1983Sci...219..979L.doi:10.1126/science.6823561.JSTOR1690734.PMID6823561.S2CID31966839.

- "Surprising Clue to Parkinson's".Time Magazine.24 June 2001. Archived fromthe originalon March 30, 2005.

- "How a Junkie's Brain Helps Parkinson's Patients".Wired.21 September 2007.

- Erowid MPTP Vault- Contains information regarding MPTP as a neurotoxin

- PBSNOVAepisode, "The Case of the Frozen Addict"https://openvault.wgbh.org/catalog/V_474CF2C8A20B4173988486AC4C605A3C

- "The MPTP Story" by J. William Langston.nih.gov.