Madhhab

| Part ofa serieson Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

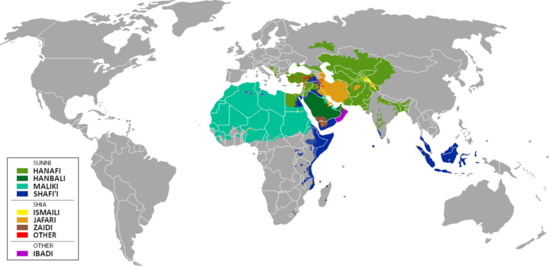

Amadhhab(Arabic:مَذْهَب,romanized:madhhab,lit. 'way to act',IPA:[ˈmaðhab],pl.مَذَاهِب,madhāhib,[ˈmaðaːhib]) refers to any school of thought withinIslamic jurisprudence.The majorSunnimadhhabareHanafi,Maliki,Shafi'iandHanbali.[1]They emerged in the ninth and tenth centuries CE and by the twelfth century almost all jurists aligned themselves with a particularmadhab.[2]These four schools recognize each other's validity and they have interacted in legal debate over the centuries.[2][1]Rulings of these schools are followed across the Muslim world without exclusive regional restrictions, but they each came to dominate in different parts of the world.[2][1]For example, the Maliki school is predominant in North and West Africa; the Hanafi school in South and Central Asia; the Shafi'i school in East Africa and Southeast Asia; and the Hanbali school in North and Central Arabia.[2][1][3]The first centuries of Islam also witnessed a number of short-lived Sunnimadhhabs.[4]TheZahirischool, which is considered to be endangered, continues to exert influence over legal thought.[4][1][2]The development ofShialegal schools occurred along the lines of theological differences and resulted in the formation of theJa'farimadhhab amongstTwelver Shias,as well as theIsma'iliandZaidimadhhabsamongstIsma'ilisandZaidisrespectively, whose differences from Sunni legal schools are roughly of the same order as the differences among Sunni schools.[4][3]TheIbadilegal school, distinct from Sunni and Shiamadhhabs,is predominant in Oman.[1]Unlike Sunnis, Shias, and Ibadis,non-denominational Muslimsare not affiliated with anymadhhab.[5][6][7]

The transformations of Islamic legal institutions in the modern era have had profound implications for themadhhabsystem. With the spread of codified state laws in the Muslim world, the influence of themadhhabsbeyond personal ritual practice depends on the status accorded to them within the national legal system. State law codification commonly drew on rulings from multiplemadhhabs,and legal professionals trained in modern law schools have largely replaced traditionalulamaas interpreters of the resulting laws.[2]In the 20th century, some Islamic jurists began to assert their intellectual independence from traditionalmadhhabs.[8]With the spread ofSalafiinfluence andreformistcurrents in the 20th century; a handful of Salafi scholars have asserted independence from being strictly bound by the traditionallegal mechanismsof the four schools. Nevertheless, the majority of Sunni scholarship continues to upholdpost-classicalcreedal belief in rigorously adhering (Taqlid) to one of the four schools in all legal details.[9]

TheAmman Message,which was endorsed in 2005 by prominent Islamic scholars around the world, recognized fourSunnischools (Hanafi,Maliki,Shafi'i,Hanbali), twoShiaschools (Ja'fari,Zaidi), theIbadischool and theZahirischool.[10]The Muslim schools of jurisprudence are located inPakistan,Iran,Bangladesh,India,Indonesia,Nigeria,Egypt,Turkey,Afghanistan,Kazakhstan,Russia,China,thePhilippines,Algeria,Libya,Saudi Arabiaand multiple other countries.

"Ancient" schools

[edit]According toJohn Burton,"modern research shows" that fiqh was first "regionally organized" with "considerable disagreement and variety of view". In the second century of Islam, schools of fiqh were noted for the loyalty of their jurists to the legal practices of their local communities, whetherMecca,Kufa,Basra,Syria, etc.[11](Egypt's school inFustatwas a branch of Medina's school of law and followed such practices—up until the end of the 8th century—as basing verdict on one single witness (not two) and the oath of the claimant. Its principal jurist in the second half of the 8th century was al-Layth b. Sa'd.)[Note 1]Al-Shafiʽiwrote that, "every capital of the Muslims is a seat of learning whose people follow the opinion of one of their countrymen in most of his teachings".[15][16]The "real basis" of legal doctrine in these "ancient schools" was not a body of reports of Muhammad's sayings, doings, silent approval (the ahadith) or even those of his Companions, but the "living tradition" of the school as "expressed in the consensus of the scholars", according to Joseph Schacht.[17]

Al-Shafi‘i and after

[edit]It has been asserted thatmadhahibwere consolidated in the 9th and 10th centuries as a means of excluding dogmatic theologians, government officials and non-Sunni sects from religious discourse.[18]Historians have differed regarding the times at which the various schools emerged. One interpretation is that Sunni Islam was initially[when?]split into four groups: theHanafites,Malikites,Shafi'itesandZahirites.[19]Later, theHanbalitesandJariritesdeveloped two more schools; then various dynasties effected the eventual exclusion of the Jarirites;[20]eventually, the Zahirites were also excluded when theMamluk Sultanateestablished a total of four independentjudicial positions,thus solidifying the Maliki, Hanafi, Shafi'i and Hanbali schools.[18]During the era of theIslamic Gunpowders,theOttoman Empirereaffirmed the official status of these four schools as a reaction to Shi'ite Persia.[21]Some are of the view that Sunni jurisprudence falls into two groups:Ahl al-Ra'i( "people of opinions", emphasizing scholarly judgment and reason) andAhl al-Hadith( "people of traditions", emphasizing strict interpretation of scripture).[22]

10th centuryShi'itescholarIbn al-Nadimnamed eight groups: Maliki, Hanafi, Shafi'i, Zahiri,Imami Shi'ite,Ahl al-Hadith, Jariri andKharijite.[20][23]Abu Thawralso had a school named after him. In the 12th century Jariri and Zahiri schools were absorbed by the Shafi'i and Hanbali schools respectively.[24]Ibn Khaldundefined only three Sunnimadhahib:Hanafi, Zahiri, and one encompassing the Shafi'i, Maliki and Hanbali schools as existing initially,[25][26]noting that by the 14th-century historian theZahirischool had become extinct,[27][28]only for it to be revived again in parts of the Muslim world by the mid-20th century.[29][30][31]

Historically, thefiqhschools were often in political and academic conflict with one another, vying for favor with the ruling government in order to have their representatives appointed to legislative and especially judiciary positions.[21]

Modern era

[edit]The transformations of Islamic legal institutions in the modern era have had profound implications for themadhhabsystem. Legal practice in most of the Muslim world has come to be controlled by government policy and state law, so that the influence of themadhhabsbeyond personal ritual practice depends on the status accorded to them within the national legal system. State law codification commonly utilized the methods oftakhayyur(selection of rulings without restriction to a particularmadhhab) andtalfiq(combining parts of different rulings on the same question). Legal professionals trained in modern law schools have largely replaced traditionalulemaas interpreters of the resulting laws. Global Islamic movements have at times drawn on differentmadhhabsand at other times placed greater focus on the scriptural sources rather than classical jurisprudence. The Hanbali school, with its particularly strict adherence to the Quran and hadith, has inspired conservative currents of direct scriptural interpretation by theSalafiandWahhabimovements.[2]In the 20th century many Islamic jurists began to assert their intellectual independence from traditional schools of jurisprudence.[8]Examples of the latter approach include networks of Indonesian ulema and Islamic scholars residing in Muslim-minority countries, who have advanced liberal interpretations of Islamic law.[2]

Schools

[edit]

Generally, Sunnis will follow one particularmadhhabwhich varies from region to region, but also believe thatijtihadmust be exercised by the contemporary scholars capable of doing so. Most rely ontaqlid,or acceptance of religious rulings and epistemology from a higher religious authority in deferring meanings of analysis and derivation of legal practices instead of relying on subjective readings.[33][34]

Experts and scholars offiqhfollow theusul(principles) of their ownmadhhab,but they also study theusul,evidences, and opinions of othermadhahib.

Sunni

[edit]Sunnischools of jurisprudence are each named after the classical jurist who taught them. The four primary Sunni schools are theHanafi,Shafi'i,MalikiandHanbalirites. TheZahirischool remains in existence but outside of the mainstream, while theJariri,Laythi,Awza'i,andThawrischools have become extinct.

The extant schools share most of their rulings, but differ on the particular practices which they may accept as authentic and the varying weights they give toanalogicalreason and pure reason.

Orthodox Sunni schools

[edit]The 4 major and 1 minor schools of thought are accepted by most scholars in most parts of the world. The Zahiri is not always accepted.

Hanafi

[edit]TheHanafischool was founded byAbu Hanifa an-Nu‘man.It is followed by Muslims in the Levant, Central Asia, Afghanistan,Pakistan,most ofIndia,Bangladesh,Northern Egypt, Iraq and Turkey and the Balkans and by most of the Muslim communities ofRussiaandChina.There are movements within this school such asBarelvisandDeobandi,which are concentrated in South Asia.

Maliki

[edit]TheMalikischool is based on thejurisprudenceofImam Malik ibn Anas.It has also been called "School of Medina" because the school was based inMedinaand the Medinian community.

It is followed by Muslims inNigeria,Algeria,North Africa,West Africa,United Arab Emirates,Kuwait,Bahrain,Upper Egypt,and in parts ofSaudi Arabia.

TheMurabitun World Movementfollows thisschoolas well. In the past, it was also followed in parts ofEurope under Islamic rule,particularlyIslamic Spainand theEmirate of Sicily.

Shafi'i

[edit]TheShafi'ischool is based upon the jurisprudence ofImam Muhammad ibn Idris ash-Shafi'i.It is followed by Muslims in theHejazregion ofSaudi Arabia,Upper Egypt,Ethiopia,Eritrea,Swahili coast,Indonesia,Malaysia,Jordan,Palestine,Philippines,Singapore,Somalia,Sri Lanka,Thailand,Yemen,Kurdistan,andsouthern India(such as theMappilasofKeralaand theKonkani Muslims). MostChechensandDagestanipeople also follow theShafi'ischool. It is the official school followed by the governments ofBruneiandMalaysia.TheShafi'ischool is also large inIraqandSyria.

Hanbali

[edit]TheHanbalischool is based on the jurisprudence ofImam Ahmad ibn Hanbalwho had been a student ofImam al-Shafi.

It is followed by Muslims inQatar,most ofSaudi Arabiaand minority communities inSyriaandIraq.There are movements that are highly influenced byHanbalifiqh such asSalafismandWahhabismconcentrated inSaudi Arabia.

Zahiri

[edit]TheZahirischool was founded byDawud al-Zahiri.It is followed by minority communities inMoroccoandPakistan.In the past, it was also followed by the majority of Muslims inMesopotamia,Portugal,theBalearic Islands,North Africaand parts ofSpain.

Shia

[edit]Ja'fari

[edit]TwelverShia adhere to theJa'faritheological school associated withJa'far al-Sadiq.In this school, the time and space boundrulingsof early jurists are taken more seriously, and the Ja'fari school uses theintellectinstead of analogy when establishing Islamic laws, as opposed to common Sunni practice.[citation needed]

Subgroups

[edit]- Usulism:forms the overwhelming majority within the Twelver Shia denomination.[citation needed]They follow aMarja-i Taqlid[clarification needed]on the subject oftaqlidand fiqh. They are concentrated in Iran, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, India, Iraq, and Lebanon.[citation needed]

- Akhbarism:similar to Usulis, however rejectijtihadin favor of hadith. Concentrated in Bahrain.[citation needed]

- Shaykhism:an Islamic religious movement founded byShaykh Ahmadin the early 19th centuryQajar dynasty,Iran, now retaining a minority following in Iran and Iraq.[citation needed]It began from a combination of Sufi and Shia and Akhbari doctrines. In the mid 19th-century many Shaykhis converted to theBábíandBaháʼíreligions, which regard Shaykh Ahmad highly.[citation needed]

Ismaili

[edit]IsmailiMuslims follow their own school in the form of theDaim al-Islam,a book on the rulings of Islam. It describes manners and etiquette, includingIbadatin the light of guidance provided by the Ismaili Imams. The book emphasizes what importance Islam has given to manners and etiquette along with the worship of God, citing the traditions of the first four Imams of the Shi'a Ismaili Fatimid school of thought.

Subgroups

[edit]- Nizari:the largest branch (95%) ofIsmaili,they are the only Shia group to have their absolute temporal leader in the rank of Imamate, which is invested in theAga Khan.Nizārī Ismailis believe that the successor-Imām to theFatimidcaliphMa'ad al-Mustansir Billahwas his elder sonal-Nizār.WhileNizārībelong to the Ja'fari jurisprudence, they adhere to the supremacy of "Kalam",in the interpretation of scripture, and believe in the temporal relativism of understanding, as opposed to fiqh(traditionallegalism),which adheres to anabsolutismapproach torevelation.

- Tāyyebī Mustā'līyyah: theMusta'aligroup of Ismaili Muslims differ from the Nizāriyya in that they believe that the successor-Imām to the Fatimid caliph, al-Mustansir, was his younger son al-Mustaʻlī, who was made Caliph by the Fatimad RegentAl-Afdal Shahanshah.In contrast to the Nizaris, they accept the younger brother al-Mustaʻlī over Nizār as their Imam. The Bohras are an offshoot of theTaiyabi,which itself was an offshoot of the Musta'ali. The Taiyabi, supporting another offshoot of the Musta'ali, theHafizibranch, split with the Musta'ali Fatimid, who recognizedAl-Amiras their last Imam. The split was due to the Taiyabi believing thatAt-Tayyib Abi l-Qasimwas the next rightful Imam afterAl-Amir.TheHafizithemselves however consideredAl-Hafizas the next rightful Imam afterAl-Amir.The Bohras believe that their 21st Imam, Taiyab abi al-Qasim, went into seclusion and established the offices of theDa'i al-Mutlaq(الداعي المطلق), Ma'zoon (مأذون) and Mukasir (مكاسر). The Bohras are the only surviving branch of the Musta'ali and themselves have split into theDawoodi Bohra,Sulaimani,Alavi Bohra,and other smaller groups.

Zaidi

[edit]ZaidiMuslims also follow their own school in the form of the teachings ofZayd ibn Aliand ImamAbu Hanifa.In terms of law, the Zaidi school is quite similar to the Hanafi school from Sunni Islam.[35]This is likely due to the general trend of Sunni resemblance within Zaidi beliefs. After the passing of Muhammad, ImamJafar al-Sadiq,ImamZayd ibn Ali,ImamsAbu Hanifaand ImamMalik ibn Anasworked together inAl-Masjid an-Nabawiin Medina along with over 70 other leading jurists and scholars.[citation needed]Jafar al-SadiqandZayd ibn Alidid not themselves write any books.[citation needed]But their views are Hadiths in the books written by ImamsAbu Hanifaand ImamMalik ibn Anas.Therefore, theZaydisto this day and originally theFatimids,used the Hanafi jurisprudence, as do most Sunnis.[36][better source needed][37][38][better source needed]

Ibadi

[edit]TheIbadischool of Islam is named afterAbd-Allah ibn Ibadh,though he is not necessarily the main figure of the school in the eyes of its adherents. Ibadism is distinct from both Sunni and Shi'ite Islam not only in terms of its jurisprudence, but also its core beliefs.IbadiIslam is mostly practiced inOman,withOmanbeing the only country in the world where Ibadis form a sizable minority of the population. Other populations of Ibadis also reside in Libya, Algeria, Tunisia and Zanzibar in Tanzania.[39]

Amman Message

[edit]TheAmman Messagewas a statement, signed in 2005 in Jordan by nearly 200 prominent Islamic jurists, which served as a "counter-fatwa" against a widespread use oftakfir(excommunication) byjihadistgroups to justifyjihadagainst rulers of Muslim-majority countries. The Amman Message recognized eight legitimate schools of Islamic law and prohibited declarations of apostasy against them.[40][41][10]

- Hanafi(Sunni)

- Maliki(Sunni)

- Shafi'i(Sunni)

- Hanbali(Sunni)

- Ja'fari(Shia)

- Zaidiyyah(Shia)

- Ibadiyyah

- Zahiriyah

The statement also asserted thatfatwascan be issued only by properly trained muftis, thereby seeking to delegitimize fatwas issued by militants who lack the requisite qualifications.[41]

See also

[edit]- Sharia(Islamic law)

- Schools of Islamic theology

- Islamic schools and branches

- Fiqh

- Ikhtilaf

- Ijtihad

- Taqlid

- Verse of Obedience

- Uli al-amr

- Istihsan

- Qiyas

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It is usually assumed that no regional school developed in Egypt (unlike in Syria, Iraq and the Hijaz). Joseph Schacht states that the legal milieu ofFustat(ancient Cairo) was a branch of the Medinan school of law.[12]Regarding judicial practices, the qadis (judges) of Fustat resorted to the procedure called "al-yamin ma'a l-shahid",that is, the ability of the judge to base his verdict on one single witness and the oath of the claimant, instead of two witnesses as was usually required. Such a procedure was quite common under the early Umayyads, but by the early Abbasid period it had disappeared in Iraq and it was now regarded as the'amal( "good practice" ) of Medina. Up until the end of the 8th century, the qadis of Fustat were still using this "Medinan" procedure and differentiated themselves from Iraqi practices. From a doctrinal point of view, however, the legal affiliation of Egypt could be more complex. The principal Egyptian jurist in the second half of the 8th century is al-Layth b. Sa'd.[13]The only writing of his that has survived is a letter he wrote to Malik b. Anas, which has been preserved by Yahya b. Ma'in and al-Fasawi. In this letter, he proclaims his theoretical affiliation to the Medinan methodology and recognizes the value of the'amal.Nevertheless, he distances himself from the Medinan School by opposing a series of Medinan legal views. He maintains that the common practice in other cities is also valuable, and thus implicitly defends the Egyptians' adherence to their own local tradition. Thus it is possible that, even though it did not develop into a formal school of law, a specific Egyptian legal milieu was distinct of the Medinan School in the 8th century.[14]

Citations

[edit]- ^abcdefRabb, Intisar A. (2009). "Fiqh". InJohn L. Esposito(ed.).The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World.Oxford:Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001.ISBN9780195305135.

- ^abcdefghHussin, Iza(2014). "Sunni Schools of Jurisprudence". In Emad El-Din Shahin (ed.).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics.Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/acref:oiso/9780199739356.001.0001.ISBN9780199739356.

- ^abVikør, Knut S. (2014)."Sharīʿah".InEmad El-Din Shahin(ed.).The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics.Oxford University Press. Archived fromthe originalon 2 February 2017.Retrieved3 September2014.

- ^abcCalder, Norman (2009)."Law. Legal Thought and Jurisprudence".In John L. Esposito (ed.).The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World.Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived fromthe originalon 21 November 2008.

- ^Tan, Charlene (2014).Reforms in Islamic Education: International Perspectives.A&C Black.ISBN9781441146175.

This is due to the historical, sociological, cultural, rational and non-denominational (non-madhhabi) approaches to Islam employed at IAINs, STAINs, and UINs, as opposed to the theological, normative and denominational approaches that were common in Islamic educational institutions in the past

- ^Rane, Halim, Jacqui Ewart, and John Martinkus. "Islam and the Muslim World." Media Framing of the Muslim World. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2014. 15-28

- ^Obydenkova, Anastassia V. "Religious pluralism in Russia." Politics of religion and nationalism: Federalism, consociationalism and secession, Routledge (2014): 36-49

- ^abMessick, Brinkley; Kéchichian, Joseph A. (2009)."Fatwā. Process and Function".In John L. Esposito (ed.).The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World.Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived fromthe originalon 20 November 2015.

- ^Auda, Jasser (2007). "5: Contemporary Theories in Islamic Law".Maqasid al-SharÏah as Philosophy of Islamic Law: A Systems Approach.669, Herndon, VA 20172, USA: The International Institute of Islamic Thought. pp. 143–145.ISBN978-1-56564-424-3.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ab"Amman Message – The Official Site".

- ^Burton,Islamic Theories of Abrogation,1990:p.13

- ^J. Schacht,The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1950), p. 9

- ^R.G. Khoury, "Al-Layth Ibn Sa'd (94/713–175/791), grand maître et mécène de l’Egypte, vu à travers quelques documents islamiques anciens",Journal of Near Eastern Studies40, 1981, p. 189–202

- ^Mathieu Tillier, "Les "premiers" cadis de Fusṭāṭ et les dynamiques régionales de l'innovation judiciaire (750–833)",Annales Islamologiques,45 (2011), p. 214–218

- ^Schacht, Joseph (1959) [1950].The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence.Oxford University Press. p. 246.

- ^Shafi'i.Kitab al-Ummvol. vii.p. 148. Kitab Ikhtilaf Malid wal-Shafi'i.

- ^Schacht, Joseph (1959) [1950].The Origins of Muhammadan Jurisprudence.Oxford University Press. p. 98.

- ^ab"Law, Islamic".Encyclopedia.com.Retrieved13 March2012.

- ^Mohammad Sharif Khan and Mohammad Anwar Saleem,Muslim Philosophy And Philosophers,pg. 34.New Delhi:Ashish Publishing House, 1994.

- ^abChristopher Melchert,The Formation of the Sunni Schools of Law:9th–10th Centuries C.E., pg. 178. Leiden:Brill Publishers,1997.

- ^abChibli Mallat,Introduction to Middle Eastern Law,pg. 116.Oxford:Oxford University Press,2007.ISBN978-0-19-923049-5

- ^Murtada Mutahhari,The Role of Ijtihad in Legislation,Al-Tawhidvolume IV, No.2, Publisher:Islamic Thought FoundationArchived14 March 2012 at theWayback Machine

- ^Devin J. Stewart,THE STRUCTURE OF THE FIHRIST: IBN AL-NADIM AS HISTORIAN OF ISLAMIC LEGAL AND THEOLOGICAL SCHOOLS,International Journal of Middle East Studies,v.39, pg.369–387,Cambridge University Press,2007

- ^Crone, Patricia (2013).The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought.Princeton University Press.p. 498.ISBN978-0691134840.Retrieved13 May2015.

- ^Ignác Goldziher,The Zahiris,pg. 5. Trns. Wolfgang Behn, intro.Camilla Adang.Volume three of Brill Classics in Islam.Leiden:Brill Publishers,2008.ISBN9789004162419

- ^Meinhaj Hussain, A New Medina,The Legal System,Grande Strategy, 5 January 2012

- ^Wolfgang, Behn (1999).The Zahiris.BRILL. p. 178.ISBN9004026320.Retrieved11 May2015.

- ^Berkey, Jonathon (2003).The Formation of Islam.Cambridge University Press. p. 216.ISBN9780521588133.Retrieved11 May2015.

- ^Daniel W. Brown,Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought:Vol. 5 of Cambridge Middle East Studies, pgs. 28 and 32.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1996.ISBN9780521653947

- ^M. Mahmood,The Code of Muslim Family Laws,pg. 37. Pakistan Law Times Publications, 2006. 6th ed.

- ^Hassan Ahmed Ibrahim, "An Overview of al-Sadiq al-Madhi's Islamic Discourse." Taken fromThe Blackwell Companion to Contemporary Islamic Thought,pg. 172. Ed. Ibrahim Abu-Rabi'.Hoboken:Wiley-Blackwell,2008.ISBN9781405178488

- ^Jurisprudence and Law – IslamReorienting the Veil, University of North Carolina (2009)

- ^"Salafi Publications | on Ijtihad and Taqlid".

- ^"On Islam, Muslims and the 500 most influential figures"(PDF).

- ^Article by Sayyid 'Ali ibn 'Ali Al-Zaidi, التاريخ الصغير عن الشيعة اليمنيين (A short History of the Yemenite Shi‘ites, 2005)

- ^El-Gamal, Mahmoud A. (3 July 2006).Islamic Finance.Cambridge University Press.ISBN9781139457163.

- ^Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla (12 May 2008).The Encyclopedia of the Arab-Israeli Conflict: A Political, Social, and...Abc-Clio.ISBN9781851098422.

- ^[better source needed]Wehrey, Frederic M.; Kaye, Dalia Dassa; Guffrey, Robert A.; Watkins, Jessica; Martini, Jeffrey (2010).The Iraq Effect.Rand Corporation.ISBN9780833047885.

- ^"UNHCR Web Archive".

- ^Hendrickson, Jocelyn (2013). "Fatwa". In Gerhard Böwering, Patricia Crone (ed.).The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought.Princeton University Press.

- ^abDallal, Ahmad S.; Hendrickson, Jocelyn (2009)."Fatwā. Modern usage".In John L. Esposito (ed.).The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World.Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived fromthe originalon 20 November 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Burton, John (1990).The Sources of Islamic Law: Islamic Theories of Abrogation(PDF).Edinburgh University Press.ISBN0-7486-0108-2.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 January 2020.Retrieved21 July2018.

- Branon Wheeler,Applying the Canon in Islam: The Authorization and Maintenance of Interpretive Reasoning in Ḥanafī Scholarship,SUNY Press,1996.

Further reading

[edit]- Haddad, Gibril F.(2007).The Four Imams and Their Schools.London: Muslim Academic Trust.

External links

[edit] Media related toMadhhabat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toMadhhabat Wikimedia Commons