Magnus Liber

MSF | |

| Author | Anonymous |

|---|---|

| Language | Latin |

| Subject | Musical score |

| Published | 13th century |

| Publication place | France |

| Website | digitalcommons |

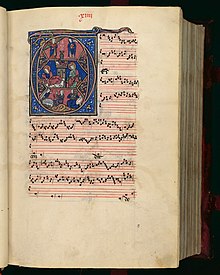

TheMagnus LiberorMagnus liber organi(English translation:Great Book of Organum), written inLatin,is a repertory ofmedieval musicknown asorganum.This collection of organum survives today in three major manuscripts. This repertoire was in use by theNotre-Dame schoolcomposers working inParisaround the end of the twelfth and beginning of the thirteenth centuries, though it is well agreed upon by scholars thatLeonincontributed a bulk of the organum in the repertoire. This large body of repertoire is known from references to a"magnum volumen"byJohannes de Garlandiaand to a"Magnus liber organi de graduali et antiphonario pro servitio divino"by theEnglishmusic theorist known asAnonymous IV.[1][2]Today it is known only from later manuscripts containing compositions named in Anonymous IV's description. TheMagnus Liberis regarded as one of the earliest collections of polyphony.

Surviving Manuscripts

[edit]TheMagnus Liber organimost likely to have originated in Paris and is known today from only a few surviving manuscripts and fragments, and there are records of at least seventeen lost versions.[1]Today its contents can be inferred from the three surviving major manuscripts:

- Florence Manuscript [F](I-FlPluteo 29.1,Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Florence) 1,023 compositions | 1250 A.D.[3]

- Wolfenbüttel 677 [W1](Wolfenbüttel Cod. Guelf. 628 Helmst.) Saint Andrews, Scotland | 1250 A.D.[3]

- Wolfenbüttel 1099 [W2](Wolfenbüttel Cod. Guelf. 1099 Helmst.) French manuscript | after 1250 A.D.[3]

These three manuscripts date from later than the originalMagnus Liber,but careful study has revealed many details regarding origin and development.[4]"Evidence of lost Notre Dame manuscripts, including the names of their owners, is plentiful indeed",[1]tracing back to year 1456 when manuscriptFfirst appeared in the library ofPiero de' Medici.Of the two others, referred to asW1&W2,both in theHerzog August Bibliothek (Ducal Library),the first is thought to have originated in the cathedralprioryof St Andrews, Scotland, and less is known aboutW2.Catalogues referring to other lost copies attest to the wide diffusion through Western Europe of the repertoire later calledars antiqua.

Heinrich Husmann summarizes that "these manuscripts, then, do not represent any more the original state of theMagnus Liber,but rather enlarged forms of it, differing from each other. In fact, these manuscripts embody different stylistic developments of theMagnus Liberitself, particularly in the field of composition mentioned by Anonymous IV, theclausula.This is born out by the differing versions of the discantus parts ".[5]Husmann also notes that a comparison of the repertory contained in the three manuscripts shows there "are a great many pieces common to all three sources" and that "the most reasonable attitude is obviously to consider the pieces in common to all three sources as the original body, consequently as the trueMagnus Liber organi ".[5]

Contributors to the Liber

[edit]It is unknown whether theMagnusLiberhad one sole contributor, though it is noted by scholars that large parts were composed byLéonin(1135–c.1200) and this conclusion is drawn from the writings of Anonymous IV.[3]Though it is a controversial topic among scholars, some believe parts of theMagnus Liber organimay have been revised byPérotin(fl. 1200), while others such as Heinrich Husmann note that the finding is from 'the rather slim report of Anonymous IV' and that 'as for its connections with Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, the name of Pérotin alone is adduced' in connection with his books having only beenused.This 'by no means confirms that Pérotin himself was active at Notre Dame, or anywhere else in Paris for that matter'.[6]

The music from theLiberhas been published in modern times byWilliam Waite(1954),[7]Hans Tischler(1989),[8]and by Edward Roesner (1993–2009).[9]

Styles and Genres of the Repertoire

[edit]

Theearly musicof Notre Dame cathedral represents a transitional time for Western culture. This time of change coincided with the architectural innovation that produced the structure of the Cathedral itself (earliest start of construction in 1163). A handful of surviving manuscripts demonstrate the evolution ofpolyphonicelaboration of the liturgicalplainchantthat was used at the cathedral every day throughout the year. While the concept of combining voices in harmony to enrich plainsong chant was not new, there lacked the established and codifiedmusical theorytechniques to enable the rational construction of such pieces.

TheMagnus Liberrepresents a step in the development ofWestern musicbetweenplainchantand the intricatepolyphonyof the later thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (seeMachautandArs Nova). The music of theMagnus Liberdisplays a connection to the emergingGothicstyle of architecture; just as ornatecathedralswere built to house holyrelics,organa were written to elaborateGregorian chant,which too was considered holy.

The innovations at Notre Dame consisted of a system ofmusical notationwhich included patterns of short and longmusical notesknown as longs andbreves.[10]This system is referred to as mensural music as it demonstrates the beginning of "measured time" in music, organizing lengths of pitches within plainchant and later, themotetgenre. In the organi of theMagnus Liber,one voice sang the notes of the Gregorian chant elongated to enormous length called the tenor (from Latin 'to hold'), but was also known as thevox principalis.As many as three voices, known as thevox organalis(orvinnola vox,the "vining voice" ) were notated above the tenor, with quicker lines moving and weaving together, a style also known asflorid organum.[11]The development from a single line of music (monophony) to one where multiple lines all carried the same weight (polyphony) is shown through the writing of organa. The practice of keeping a slow moving "tenor" line continued into secular music, and the words of the original chant survived in some cases as well. One of the most common genres in theMagnus Liberis theclausula,which are "sections where, indiscantstyle, the tenor uses rhythmic patterns as well as the upper part ".[5]These sections of polyphony were substituted into longer organa. The extant manuscripts provide a number of notational challenges for modern editors since they contain only the polyphonic sections to which the monophonic chant must be added.

References

[edit]- ^abcBaltzer, Rebecca A. (1987-07-01)."Notre Dame Manuscripts and Their Owners: Lost and Found".Journal of Musicology.5(3): 380–399.doi:10.2307/763698.ISSN0277-9269.JSTOR763698.

- ^Roesner, Edward H. (September 2001)."Who 'Made' the Magnus Liber?".Early Music History.20.doi:10.1017/S0261127901001061.ISSN0261-1279.S2CID190695312.

- ^abcdWright, Craig M. (1989).Music and ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500-1550.Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-24492-7.OCLC18521286.

- ^Smith, Norman E. (January 1973)."Interrelationships among the Graduals of the Magnus Liber Organi".Acta Musicologica.45(1): 73–97.doi:10.2307/932223.JSTOR932223.

- ^abcHusmann, Heinrich; Briner, Andres P. (1963-07-01)."The Enlargement of the Magnus liber organi and the Paris Churches St. Germain l'Auxerrois and Ste. Geneviève-du-Mont".Journal of the American Musicological Society.16(2): 176–203.doi:10.2307/829940.ISSN0003-0139.JSTOR829940.

- ^Husmann, Heinrich (1963)."The Origin and Destination of the Magnus Liber Organi".The Musical Quarterly.XLIX(3): 311–330.doi:10.1093/mq/XLIX.3.311.ISSN0027-4631.

- ^Waite, William G. (1973) [1954].The rhythm of twelfth-century polyphony: its theory and practice.Léonin. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press.ISBN0-8371-6815-5.OCLC622500.

- ^Tischler, Hans (July 1977)."The Structure of Notre-Dame Organa".Acta Musicologica.49(2): 193–199.doi:10.2307/932589.JSTOR932589.

- ^Le Magnus liber organi de Notre-Dame de Paris.Roesner, Edward H. Monaco: Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre. 1993.ISBN2-87855-000-5.OCLC17699186.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^"Magnus liber".publications.cedarville.edu.Retrieved2020-12-09.

- ^Bradley, Catherine A. (2019)."Choosing a Thirteenth-Century Motet Tenor: From the Magnus liber organi to Adam de la Halle".Journal of the American Musicological Society.72(2): 431–492.doi:10.1525/jams.2019.72.2.431.hdl:10852/76335.ISSN0003-0139.S2CID202522259.

Further reading

[edit]- Chew, Geoffrey(Summer 1978). "AMagnus Liber OrganiFragment at Aberdeen ".Journal of the American Musicological Society.31(2): 326–343.doi:10.2307/831000.JSTOR831000.