Mandala

Amandala(Sanskrit:मण्डल,romanized:maṇḍala,lit. 'circle',[ˈmɐɳɖɐlɐ]) is a geometric configuration of symbols. In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for establishing asacred spaceand as an aid tomeditationandtranceinduction. In theEastern religionsofHinduism,Buddhism,JainismandShintoit is used as a map representing deities, or especially in the case of Shinto, paradises,kamior actual shrines.[1][2]

Hinduism[edit]

In Hinduism, a basic mandala, also called ayantra,takes the form of a square with four gates containing a circle with acenter point.Each gate is in the general shape of a T.[3]Mandalas often haveradialbalance.[4]

Ayantrais similar to a mandala, usually smaller and using a more limited colour palette. It may be a two- or three-dimensional geometric composition used insadhanas,puja or meditative rituals, and may incorporate amantrainto its design. It is considered to represent the abode of the deity. Eachyantrais unique and calls the deity into the presence of the practitioner through the elaborate symbolic geometric designs. According to one scholar, "Yantras function as revelatory symbols of cosmic truths and as instructional charts of the spiritual aspect of human experience"[5]

Many situateyantrasas central focus points for Hindu tantric practice.Yantrasare not representations, but are lived, experiential,nondualrealities. As Khanna describes:

Despite its cosmic meanings ayantrais a reality lived. Because of the relationship that exists in theTantrasbetween the outer world (the macrocosm) and man's inner world (the microcosm), every symbol in ayantrais ambivalently resonant in inner–outer synthesis, and is associated with the subtle body and aspects of human consciousness.[6]

The term 'mandala' appears in theRigvedaas the name of the sections of the work, andVedic ritualsuse mandalas such as theNavagrahamandala to this day.[7]

Buddhism[edit]

Vajrayana[edit]

InVajrayanaBuddhism, mandalas have been developed also intosandpainting.They are also a key part ofAnuttarayoga Tantrameditation practices.[8]

Visualisation of Vajrayana teachings[edit]

The man mandala can be shown to represent in visual form the core essence of theVajrayanateachings. The mandala represents the nature of the Pure Land, Enlightened mind.

An example of this type of mandala isVajrabhairava mandalaa silk tapestry woven with gilded paper depicting lavish elements like crowns and jewelry, which gives a three-dimensional effect to the piece.[9][10]

Mount Meru[edit]

A mandala can also represent the entire universe, which is traditionally depicted withMount Meruas theaxis mundiin the center, surrounded by the continents.[11]One example is theCosmological Mandala with Mount Meru,asilktapestryfrom theYuan dynastythat serves as a diagram of the Tibetan cosmology, which was given to China from Nepal and Tibet.[12][13]

Wisdom and impermanence[edit]

In the mandala, the outer circle of fire usually symbolises wisdom. The ring of eightcharnel grounds[14]represents theBuddhistexhortation to be always mindful of death, and the impermanence with whichsamsarais suffused: "such locations were utilized in order to confront and to realize the transient nature of life".[15]Described elsewhere: "within a flaming rainbow nimbus and encircled by a black ring ofdorjes,the major outer ring depicts the eight great charnel grounds, to emphasize the dangerous nature of human life ".[16]Inside these rings lie the walls of the mandala palace itself, specifically a place populated by deities andBuddhas.

Five Buddhas[edit]

One well-known type of mandala is the mandala of the "Five Buddhas", archetypal Buddha forms embodying various aspects of enlightenment. Such Buddhas are depicted depending on the school ofBuddhism,and even the specific purpose of the mandala. A common mandala of this type is that of theFive Wisdom Buddhas(a.k.a. FiveJinas), the BuddhasVairocana,Aksobhya,Ratnasambhava,AmitabhaandAmoghasiddhi.When paired with another mandala depicting theFive Wisdom Kings,this forms theMandala of the Two Realms.

Practice[edit]

Mandalas are commonly used by tantric Buddhists as an aid to meditation.

The mandala is "a support for the meditating person",[17]something to be repeatedly contemplated to the point of saturation, such that the image of the mandala becomes fully internalised in even the minutest detail and can then be summoned and contemplated at will as a clear and vivid visualized image. With every mandala comes what Tucci calls "its associated liturgy... contained in texts known astantras",[18]instructing practitioners on how the mandala should be drawn, built and visualised, and indicating themantrasto be recited during its ritual use.

By visualizing "pure lands", one learns to understand experienceitselfas pure, and as the abode of enlightenment. The protection that we need, in this view, is from our own minds, as much as from external sources of confusion. In many tantric mandalas, this aspect of separation and protection from the outer samsaric world is depicted by "the four outer circles: the purifying fire of wisdom, thevajracircle, the circle with the eight tombs, the lotus circle ".[17]The ring ofvajrasforms a connected fence-like arrangement running around the perimeter of the outer mandala circle.[19]

As a meditation on impermanence (a central teaching ofBuddhism), after days or weeks of creating the intricate pattern of asand mandala,the sand is brushed together into a pile and spilled into a body of running water to spread the blessings of the mandala.

Kværne[20]in his extended discussion ofsahaja,discusses the relationship ofsadhanainteriority and exteriority in relation to mandala thus:

...external ritual and internal sadhana form an indistinguishable whole, and this unity finds its most pregnant expression in the form of the mandala, the sacred enclosure consisting of concentric squares and circles drawn on the ground and representing that adamant plane of being on which the aspirant to Buddha hood wishes to establish himself. The unfolding of the tantric ritual depends on the mandala; and where a material mandala is not employed, the adept proceeds to construct one mentally in the course of his meditation. "[21]

Offerings[edit]

A "mandala offering"[22]inTibetan Buddhismis a symbolic offering of the entire universe. Every intricate detail of these mandalas is fixed in the tradition and has specific symbolic meanings, often on more than one level.

Whereas the above mandala represents the pure surroundings of a Buddha, this mandala represents the universe. This type of mandala is used for the mandala-offerings, during which one symbolically offers the universe to the Buddhas or to one's teacher. Within Vajrayana practice, 100,000 of these mandala offerings (to create merit) can be part of the preliminary practices before a student even begins actual tantric practices.[23]This mandala is generally structured according to the model of the universe as taught in a Buddhist classic text theAbhidharma-kośa,withMount Meruat the centre, surrounded by the continents, oceans and mountains, etc.

Theravada Buddhism[edit]

Various Mandalas are described in manyPali Buddhist texts.Some of the examples of theTheravadaBuddhist Mandalas are:

- Mandala of Eight Disciplesof Buddha describing theShakyamuni Buddhaat center and Eight great disciple in eight major directions.

- Mandala of Buddhasis the mandala consisting of nine major Buddhas of the past and the presentGautama Buddhaoccupying the ten directions.

- Mandala of Eight Devisincludes the eight Devis occupying and protecting the eight corners of the Universe.

InSigālovāda Sutta,Buddha describes the relationships of a commonlay personsin Mandala style.

Shingon Buddhism[edit]

One Japanese branch of Mahayana Buddhism –ShingonBuddhism – makes frequent use of mandalas in its rituals as well, though the actual mandalas differ. When Shingon's founder,Kūkai,returned from his training in China, he brought back two mandalas that became central to Shingon ritual: theMandala of the Womb Realmand theMandala of the Diamond Realm.

These two mandalas are engaged in theabhisekainitiation rituals for new Shingon students, more commonly known as theKechien Kanjō(Kết duyên quán đỉnh). A common feature of this ritual is to blindfold the new initiate and to have them throw a flower upon either mandala. Where the flower lands assists in the determination of whichtutelary deitythe initiate should follow.

Nichiren Buddhism[edit]

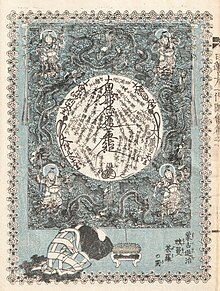

The mandala inNichiren Buddhismis amoji-mandala(Văn tự mạn đà la), which is a paperhanging scrollor wooden tablet whose inscription consists ofChinese charactersandmedieval-Sanskrit scriptrepresenting elements of the Buddha'senlightenment,protective Buddhist deities, and certain Buddhist concepts. Called theGohonzon,it was originally inscribed byNichiren,the founder of this branch ofJapanese Buddhism,during the late 13th Century. TheGohonzonis the primary object of veneration in some Nichiren schools and the only one in others, which consider it to be the supreme object of worship as the embodiment of the supremeDharmaand Nichiren's inner enlightenment. The seven charactersNamu Myōhō Renge Kyō,considered to be the name of the supreme Dharma, as well as theinvocationthat believers chant, are written down the center of all Nichiren-sectGohonzons,whose appearance may otherwise vary depending on the particular school and other factors.[citation needed]

Pure Land Buddhism[edit]

Mandalas have sometimes been used inPure Land Buddhismto graphically representPure Lands,based on descriptions found in theLarger Sutraand theContemplation Sutra.The most famous mandala in Japan is theTaima mandala,dated to about 763 CE. The Taima mandala is based on theContemplation Sutra,but other similar mandalas have been made subsequently. Unlike mandalas used inVajrayanaBuddhism, it is not used as an object of meditation or for esoteric ritual. Instead, it provides a visual representation of the Pure Land texts, and is used as a teaching aid.[citation needed]

Also inJodo ShinshuBuddhism,Shinranand his descendant,Rennyo,sought a way to create easily accessible objects of reverence for the lower-classes of Japanese society. Shinran designed a mandala using a hanging scroll, and the words of thenembutsu(Niệm phật) written vertically. This style of mandala is still used by someJodo ShinshuBuddhists in home altars, orbutsudan.[citation needed]

Bodhimandala[edit]

Bodhimaṇḍala is a term inBuddhismthat means "circle ofawakening".[24]

Sand mandalas[edit]

Sand mandalasare colorful mandalas made from sand that are ritualistically destroyed. They originated in India in the 8th–12th century but are now practiced in Tibetan Buddhism.[25]Each mandala is dedicated to specific deities. In Buddhism Deities represent states of the mind to be obtained on the path to enlightenment, the mandala itself is representative of the deity's palace which also represents the mind of the deity.[25]Each mandala is a pictorial representation of atantra.for the process of making Sand mandalas they are created by monks who have trained for three–five years in a monastery.[26]These sand mandalas are made to be destroyed to symbolize impermanence, the Buddhist belief that death is not the end, and that one's essence will always return to the elements. It is also related to the belief that one should not become attached to anything.[27]To create these mandalas, the monks first create a sketch,[28]then take colorful sand traditionally made from powdered stones and gems into copper funnels called Cornetts[26]and gently tap sand out of them to create the sand mandala. Each color represents attributes of deities. While making the mandalas the monks will pray and meditate, each grain of sand represents a blessing.[27]Monks will travel to demonstrate this art form to people, often in museums.

Western psychological interpretations[edit]

The re-introduction of mandalas into modern Western thought is largely credited to psychologistCarl Gustav Jung.In his exploration of the unconscious through art, Jung observed the common appearance of a circle motif across religions and cultures. He hypothesized that the circle drawings reflected the mind's inner state at the moment of creation and were a kind of symbolic archetype in the collective unconscious. Familiarity with the philosophical writings of India prompted Jung to adopt the word "mandala" to describe these drawings created by himself and his patients. In his autobiography, Jung wrote:

I sketched every morning in a notebook a small circular drawing, [...] which seemed to correspond to my inner situation at the time. [...] Only gradually did I discover what the mandala really is: [...] the Self, the wholeness of the personality, which if all goes well is harmonious.

— Carl Jung,Memories, Dreams, Reflections,pp. 195–196. p.232 Vintage books revised edition (Doubleday)

When I began drawing the mandalas, however, I saw that everything, all the paths I had been following, all the steps I had taken, were leading back to a single point—namely, to the mid-point. It became increasingly plain to me that the mandala is the center. It is the exponent of all paths. It is the path to the center, to individuation....I saw that here the goal had been revealed. One could not go beyond the center. The center is the goal, and everything is directed toward that center. Through this dream I understood that the self is the principle and archetype of orientation and meaning. Therein lies its healing function. For me, this insight signified an approach to the center and therefore to the goal.

— Carl Jung,Memories, Dreams, Reflections,pp. 233-235 Vintage Books revised edition (Doubleday)

Jung claimed that the urge to make mandalas emerges during moments of intense personal growth. He further hypothesized their appearance indicated a "profound re-balancing process" is underway in the psyche; the result of the process would be a more complex and better integrated personality.

The mandala serves a conservative purpose – namely, to restore a previously existing order. But it also serves the creative purpose of giving expression and form to something that does not yet exist, something new and unique. [...] The process is that of the ascending spiral, which grows upward while simultaneously returning again and again to the same point.

— Marie-Louise von Franz,InMan and His Symbols(C. G. Jung, Ed.), p. 225,

American art therapist Joan Kellogg later created the MARI card test, afree response measure,based on Jung's work.[29]

Transpersonal psychologistDavid Fontanaproposed that the symbolic nature of a mandala may help one "to access progressively deeper levels of the unconscious, ultimately assisting the meditator to experience a mystical sense of oneness with the ultimate unity from which the cosmos in all its manifold forms arises."[30]

In architecture[edit]

Buddhist architectureoften applied mandala as the blueprint or plan to design Buddhist structures, includingtemple complexand stupas.[citation needed]A notable example of mandala in architecture is the 9th centuryBorobudurin Central Java, Indonesia. It is built as a largestupasurrounded by smaller ones arranged on terraces formed as astepped pyramid,and when viewed from above, takes the form of a gianttantric Buddhistmandala, simultaneously representing the Buddhist cosmology and the nature of mind.[31]Other temples from the same period that also have mandala plans includeSewu,PlaosanandPrambanan.Similar mandala designs are also observable in Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar.

-

Aerial view of theBoudhanath stuparesembles a mandala

-

Borobudur ground plan taking the form of a Mandala

-

7th century buddhist monastery in Bangladesh.Somapura Mahavihara

In science[edit]

Circular diagrams are often used inphylogenetics,especially for the graphical representation of phylogenetic relationships.Evolutionary treesoften encompass numerous species that are conveniently shown on a circular tree, with images of the species shown on the periphery of a tree. Such diagrams have been called phylogenetic mandalas.[32]

In art[edit]

Mandala as an art form first appeared in Buddhist art that were produced in India during the first century B.C.E.[33]These can also be seen inRangolidesigns in Indian households.

In archaeology[edit]

One of the most intense archaeological discoveries in recent years that could redefine the history of eastern thought and tradition of mandala is the discovery of five giant mandalas in the valley ofManipur,India, made with Google Earth imagery. Located in the paddy field in the west ofImphal,the capital of Manipur, the Maklang geoglyph is perhaps the world's largest mandala built entirely of mud. The site wasn't discovered until 2013 as its whole structure could only be visible via Google Earth satellite imagery. The whole paddy field, locally known asBihu Loukon,is now protected and announced as historical monument and site by the government of Manipur in the same year. The site is situated 12 km aerial distance fromKanglawith the GPS coordinates of 24° 48' N and 93° 49' E. It covers a total area of around 224,161.45 square meters. This square mandala has four similar protruding rectangular ‘gates’ in the cardinal directions guarded each by similar but smaller rectangular ‘gates’ on the left and right. Within the square there is an eight petalled flower or rayed-star, recently called as Maklang ‘Star fort’ by the locals, in the centre covering a total area of around 50,836.66 square meters. The discovery of other five giant mandalas in the valley of Manipur is also made with Google Earth. The five giant mandalas, viz., Sekmai mandala, Heikakmapal mandala, Phurju twin mandalas and Sangolmang mandala are located on the western bank of the Iril River.[34]Another two fairly large mandala shaped geoglyph at Nongren and Keinou are also reported from Manipur valley, India, in 2019. They are named as Nongren mandala and Keinou mandala.[35]

In politics[edit]

TheRajamandala(orRaja-mandala;circle of states) was formulated by theIndianauthorKautilyain his work on politics, theArthashastra(written between 4th century BCE and 2nd century BCE). It describes circles of friendly and enemy states surrounding the king's state.[36]

In historical, social and political sense, the term "mandala" is also employed to denote traditionalSoutheast Asian political formations(such as federation of kingdoms or vassalized states). It was adopted by 20th century Western historians from ancient Indian political discourse as a means of avoiding the term 'state' in the conventional sense. Not only did Southeast Asian polities not conform to Chinese and European views of a territorially defined state with fixed borders and a bureaucratic apparatus, but they diverged considerably in the opposite direction: the polity was defined by its centre rather than its boundaries, and it could be composed of numerous other tributary polities without undergoing administrative integration.[37]Empires such asBagan,Ayutthaya,Champa,Khmer,SrivijayaandMajapahitare known as "mandala" in this sense.

In contemporary use[edit]

Fashion designerMandali Mendrilladesigned an interactive art installation called Mandala of Desires (Blue Lotus Wish Tree) made in peace silk and eco friendly textile ink, displayed at theChina Art Museumin Shanghai in November 2015. The pattern of the dress was based on the Goloka Yantra mandala, shaped as a lotus with eight petals. Visitors were invited to place a wish on the sculpture dress, which will be taken to India and offered to a genuine livingWish Tree.[38][39]

Gallery[edit]

-

Cosmological mandala with Mount Meru,silk tapestry, China via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Vajrabhairava mandala,silk tapestry, China via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

A diagramic drawing of theSri Yantra,showing the outside square, with four T-shaped gates, and the central circle

-

Painted 19th centuryTibetanmandala of theNaropatradition,Vajrayoginistands in the center of two crossed red triangles,Rubin Museum of Art

-

PaintedBhutaneseMedicine Buddhamandala withthe goddess Prajnaparamitain center, 19th century,Rubin Museum of Art

-

Mandala of the SixChakravartins

-

Vajravarahimandala

-

Jaincosmological diagrams and text.

-

Mandala painted by a patient of Carl Jung

-

Kalachakra mandala in a special glass pavilion. Buddhist pilgrims bypass the pavilion in a clockwise direction three times.Buryatiya, July 16, 2019

-

Mandala in Maitighar, Kathmandu, Nepal

See also[edit]

- Shamsa– Intricately decorated rosette or medallion which is used in many contexts, including manuscripts, carpets, ornamental metalwork and architectural decoration such as the underside of domes

- Architectural drawing– Technical drawing of a building (or building project)

- Astrological symbols– Symbols denoting astrological concepts

- Bhavacakra– A symbolic representation of cyclic existence

- Chakra– Subtle body psychic-energy centers in the esoteric traditions of Indian religions

- Dharmachakra– Symbol in Dharmic religions

- Form constant– Recurringly observed geometric pattern

- Ganachakra– Tantric assemblies or feasts

- Great chain of being– Cosmological hierarchy of all matter and life

- Luoshu Square– Chinese name for a specific 3x3 magic square occurring in legendary accounts of the creation of Chinese writing and culture

- Hilya– artwork depicting the appearance of character of Muhammad

- Khorlo

- Ley line– Straight alignments between historic structures and landmarks

- Magic circle– Protective device in ritual magic

- Mandylion– A painting of Jesus Christ's face

- Namkha– Tibetan form of yarn or thread cross

- Religious art– Art with religious subjects

- Shri Yantra– Form of mystical diagram used in the Shri Vidya school of Hinduism

- Sriramachakra– Device used in astrolgy in Tamil Nadu

- Tree of life (Kabbalah)– Diagram used in various mystical traditions

- Yantra– Mystical diagram in Tantric traditions

Citations[edit]

- ^"mandala".Merriam–Webster Online Dictionary. 2008.Archivedfrom the original on 2018-12-26.Retrieved2008-11-19.

- ^Tanabe, Willa Jane (2001). "Japanese Mandalas: Representations of Sacred Geography".Japanese Journal of Religious Studies.28(1/2): 186–188.JSTOR30233691.

- ^"Kheper,The Buddhist Mandala – Sacred Geometry and Art".Archived fromthe originalon 2011-05-14.Retrieved2010-05-08.

- ^www.sbctc.edu (adapted)."Module 4: The Artistic Principles"(PDF).Saylor.org.Archived(PDF)from the original on 20 January 2013.Retrieved2 April2012.

- ^Khanna Madhu,Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity.Thames and Hudson, 1979, p. 12.

- ^Khanna, Madhu,Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity.Thames and Hudson, 1979, pp. 12-22

- ^"Handbook to the Study of the Rigveda: Part II-The Seventh Mandala of the Rig Veda".INDIAN CULTURE.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-10-15.Retrieved2022-10-10.

- ^"Mandala in Buddhism | Buddhist Art".www.buddhist-art.com.Retrieved2024-03-14.

- ^"Vajrabhairava Mandala".The Metropolitan Museum of Art.Archivedfrom the original on 2 December 2017.Retrieved19 November2017.

- ^Watt, James C.Y. (1997).When Silk was Gold: Central Asian and Chinese Textiles.New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 95.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-12-19.Retrieved2017-11-19.

- ^Mipham (2000) pp. 65,80

- ^"Cosmological Mandala with Mount Meru".The Metropolitan Museum of Art.Archivedfrom the original on 5 December 2017.Retrieved19 November2017.

- ^Watt, James C.Y. (2010).The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty.New York: Yale University Press. p. 247.Archivedfrom the original on 7 December 2017.Retrieved19 November2017.

- ^O'Donnell, Julie; White, Pennie; Oellien, Rilla; Halls, Evelin (13 August 2003)."A Monograph on a Vajrayogini Thanka Painting".Consultant: John D. Hughes. Archived fromthe originalon 13 August 2003.

- ^Camphausen, Rufus C."Charnel- and Cremation Grounds".Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2016.Retrieved10 October2016.

- ^"Tibet and the Himalayas".Sootze Oriental Antiques.Archived fromthe originalon 2006-03-03.Retrieved2006-11-25.

- ^ab"Mandala".Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2016.Retrieved10 October2016.

- ^"The Mandala in Tibet".Archivedfrom the original on 13 August 2016.Retrieved10 October2016.

- ^"Mandala".Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2016.Retrieved10 October2016.

- ^Per Kvaerne 1975: p. 164

- ^Kvaerne, Per (1975).On the Concept of Sahaja in Indian Buddhist Tantric Literature. (NB: article first published inTemenosXI (1975): pp.88-135). Cited in: Williams, Jane (2005).Buddhism: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies, Volume 6.Routledge. ISBN 0-415-33226-5, ISBN 978-0-415-33226-2.Routledge.ISBN9780415332323.Archivedfrom the original on September 25, 2021.RetrievedApril 16,2010.

- ^"What Is a Mandala?".studybuddhism.com.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-09-17.Retrieved2016-06-06.

- ^"Preliminary practice (ngöndro) overview".September 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 4 July 2014.Retrieved10 October2016.

- ^Thurman, Robert.The Holy Teaching of Vimalakīrti: A Mahāyāna Scripture.1992. p. 120

- ^abBryant, Barry (1992).Wheel of time Sand Mandala.San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

- ^ab"Sand Painting: Sacred Art of Tibet.", directed by Sheri Brenner, produced by Sheri Brenner, Berkeley Media, 2002. Alexander Street,https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/sand-painting-sacred-art-of-tibet.

- ^ab"Sand mandala: Tibetan Buddhist ritual".YouTube.Wellcome Collection.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-07-15.Retrieved2021-07-21.

- ^"TIBETAN MONKS CREATE SAND MANDALA LIVE".The Rubin.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-07-15.Retrieved2021-07-21.

- ^Kellogg, Joan. (1984).Mandala: path of beauty.Lightfoot, VA: MARI.ISBN0-9631949-1-7.OCLC30430100.

- ^Fontana, David. (2006).Meditating with Mandalas: 52 New Mandalas to Help You Grow in Peace and Awareness.Duncan Baird.ISBN978-1-84-483117-3.

- ^A. Wayman (1981). "Reflections on the Theory of Barabudur as a Mandala".Barabudur History and Significance of a Buddhist Monument.Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press.

- ^Hasegawa, Masami (2017). "Phylogeny mandalas for illustrating the Tree of Life".Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.117:168–178.doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.11.001.PMID27816710.

- ^"Exploring the Mandala".Asia Society.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-02-14.Retrieved2021-03-15.

- ^Wangam, Somorjit (2018).World's Largest Mandalas from Manipur and Carl Jung's Archetype of the Self,p. 25-33. NeScholar, ed. Dr. R.K.Nimai Singh,Imphal.ISSN2350-0336.

- ^Wangam, Somorjit (2019).Emerging The Lost Civilization of The Manipur Valley,p. 30-39. NeScholar, ed. Dr. R.K.Nimai Singh,Imphal.ISSN2350-0336.

- ^Singh, Prof. Mahendra Prasad (2011).Indian Political Thought: Themes and ThinkersArchived2016-06-10 at theWayback Machine.Pearson Education India.ISBN8131758516.pp. 11-13.

- ^Dellios, Rosita (2003-01-01)."Mandala: from sacred origins to sovereign affairs in traditional Southeast Asia".Bond University Australia. Archived fromthe originalon 2015-02-03.Retrieved2011-12-11.

- ^"China Art Museum in Shanghai - Forms of Devotion".14 November 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2016.Retrieved10 October2016.

- ^"Haljinu" Mandala of Desires "dnevno posjećuje čak 30 000 ljudi!".3 December 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-12-22.Retrieved2015-12-15.

General sources[edit]

- Brauen, M. (1997).The Mandala, Sacred circle in Tibetan BuddhismSerindia Press, London.

- Bucknell, Roderick & Stuart-Fox, Martin (1986).The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism.Curzon Press: London.ISBN0-312-82540-4

- Cammann, S.(1950).Suggested Origin of the Tibetan Mandala PaintingsThe Art Quarterly, Vol. 8, Detroit.

- Cowen, Painton (2005).The Rose Window,London and New York, (offers the most complete overview of the evolution and meaning of the form, accompanied by hundreds of colour illustrations.)

- Crossman, Sylvie and Barou, Jean-Pierre (1995).Tibetan Mandala, Art & PracticeThe Wheel of Time, Konecky and Konecky.

- Fontana, David (2005). "Meditating with Mandalas", Duncan Baird Publishers, London.

- Gold, Peter(1994).Navajo & Tibetan sacred wisdom: the circle of the spirit.Inner Traditions/Bear.ISBN0-89281-411-X.Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International.

- Mipham, Sakyong Jamgön (2002)2000 Seminary Transcripts Book 1Vajradhatu PublicationsISBN1-55055-002-0

- Somorjit, Wangam (2018). "World's Largest Mandalas from Manipur and Carl Jung's Archetype of the Self", neScholar, vol.04, Issue 01, ed.Dr. R.K. Nimai SinghISSN2350-0336

- Tucci, Giuseppe (1973).The Theory and Practice of the Mandalatrans. Alan Houghton Brodrick, New York, Samuel Weisner.

- Vitali, Roberto (1990).Early Temples of Central TibetLondon, Serindia Publications.

- Wayman, Alex (1973)."Symbolism of the Mandala Palace"inThe Buddhist TantrasDelhi, Motilal Banarsidass.

Further reading[edit]

- Grotenhuis, Elizabeth Ten (1999). Japanese mandalas: representations of sacred geography, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press

- Kossak, S. (1998).Sacred visions: early paintings from central Tibet.New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.(see index)