Maralinga Tjarutja

| Maralinga Tjarutja South Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

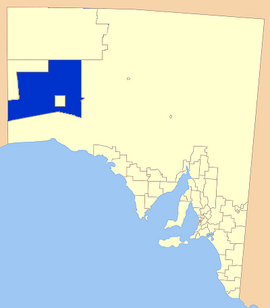

Location of the Maralinga Tjarutja Council | |||||||||||||||

| Population | 96 (LGA2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 0.001/km2(0.0026/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 2006 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 102,863.6 km2(39,715.9 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Council seat | Ceduna(outside Council area) | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Eyre Western[2] | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Flinders | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Grey | ||||||||||||||

| Website | Maralinga Tjarutja | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

TheMaralinga Tjarutja,orMaralinga Tjarutja Council,is the corporation representing the traditionalAnanguowners of the remote western areas ofSouth Australiaknown as the Maralinga Tjarutja lands. The council was established by theMaralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act 1984.The area is one of the four regions of South Australia classified as anAboriginal Council(AC), and its official consideration as alocal government areadiffers between federal and state sources.

TheAboriginal Australianpeople whose historic rights over the area have been officially recognised belong to the southern branch of thePitjantjatjara people.The land includes a large area of land contaminated byBritish nuclear testing in the 1950s,for which the inhabitants were eventually compensated in 1991.

There is a community centre atOak Valley,840 km (520 mi) NW ofCeduna,and close historical and kinship links with theYalata350 km (220 mi) south, and thePila Ngurucentre ofTjuntjuntjara370 km (230 mi) to their west.[3]

Languages and peoples

[edit]The Maralinga Tjarutja people belong to a generalWestern Desert ecological zonesharing cultural affinities with thePitjantjatjara,YankunytjatjaraandNgaanyatjarrato their north and thePila Nguruof the spinifex plains to their west, They speak dialects ofPitjantjatjaraandYankunytjatjara.[4]

Ecology and cultural beliefs

[edit]The termmaralingais not of local origin. It is a term chosen from the Garig or Garik dialect of the now-extinctNorthern TerritoryIlgar language,signifying "field of thunder/thunder", and was selected to designate the area whereatomic bomb testingwas to be undertaken by the then Chief Scientist of theDepartment of Supply,W. A. S. Butement.[5]The land was covered inspinifex grasses[6]and good red soil (parna wiru) furnishing fine camping.[7]

Waterholes (kapi) have a prominent function in their mythology: they are inhabited by spirit children and thought of as birth places, and control of them demarcate the various tribal groups.[8]According toRonald Berndt,one particular water snake,Wanampi,tutelage spirit over native doctors, whose fertility function appears to parallel in some respects that of theRainbow serpentofArnhem Landmyth, was regarded as the creator of thesekapi,and figured prominently in male initiation ceremonies.[9]

Contact

[edit]OoldeaorYuldi/Yutulynga/Yooldool(the place of abundant water) sits on a permanent undergroundaquifer.[4]The area is thought to have been originally part ofWiranguland, lying on its northern border,[10]though it fell within the boundaries of aKokathaemu totem group. It served several Aboriginal peoples, furnishing them with aceremonial site,trade node and meeting place for other groups, from the northeast who would travel several hundred miles to visit kin. Among the peoples who congregated there were tribes from the Kokatha andNgaleanorthern groups and Wirangu of south-east andMirningsouth-west.[11]By the timeDaisy Bates(1919–1935) took up residence there it was thought that earlier groups had disappeared, replaced by an influx ofspinifex peoplefrom the north. By her time, theTrans-Australian Railwayroute had just been completed, coinciding with a drought that drew theWestern desert peoplesto the depot at Ooldea.[11][12]

Beginning in the 1890s, there was a gradual encroachment by pastoralists up to the southern periphery of theNullarbor Plain,but the lack of adequate water to sustain stock maintained the region relatively intact from intense exploitation.[12]In 1933 the United Aborigines Missions established itself there, drawing substantial numbers of desert folk to the site for food and clothing, and four years later, the government established a 2,000-square-mile (5,200 km2) reserve.[12]In 1941, the anthropologistsRonaldandCatherine Berndtspent several months in the Aboriginal camp at the water soak and mission, and in the following three-year period (1942–1945) wrote one of the first scientific ethnographies of an Australian tribal group, based on his interviews in a community of some 700 desert people.[13]Traditional life still continued since Ooldea lay on the fringe of the desert, and incoming Aboriginal people could return to their old hunting style.

Nuclear testing, dispossession and return

[edit]When theAustralian Governmentdecided in the early 1950s to set aside theEmu FieldandMaralingain the area forBritish nuclear testing,the community at Ooldea was forcibly removed from the land and resettled further south atYalata,in 1952. Road blocks and soldiers barred any return.[6]

Yalata, bordering on theNullarbor Plainoffered a totally differentecologicalenvironment; in place of thespinifexplains to the north, the Maralinga Tjaruta people found an arid stone plain, with poor thin soil and a powdery limestone that kicked up a grey dust when disturbed. Their word for "grey", namelytjilpialso signified the greying elders of a tribe, and the Aboriginal residents of Yalata called the new areaparna tjilpi,the "grey earth/ground", suggesting that their forced relocation to Yalata went concomitantly with ageing towards death.[14]

Between 1956 and 1957, seven atomic bombs were exploded on Maralinga land. In further minor trials from 1957 to 1962,plutoniumwas dispersed widely over much of the area.[15]Compensation in 1993 ofA$13.5 millionwas determined after three elders flew to London and presented samples of the contaminated soil in London in October 1991.[16]

In 1962, the long-servingPremier of South Australia,Sir Thomas Playford,made a promise that their traditional lands would be restored to the people displaced at Yalata sometime in the future.[17]Under the administration of his successorFrank Walsh,short two-week long bush trips were permitted, enabling them to re-connect with their traditional lifestyles.[14]As negotiations got underway in the 1980s, the Indigenous peoples started setting upoutstationsnear their original lands. With the passage of theMaralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act 1984under PremierJohn Bannon's government, the Maralinga Tjarutja securedfreehold titlein 1984, and the right to developmental funds from the State and Federal governments. They completed a move back into the area, to a new community calledOak Valleyin March 1985.[18]

Under an agreement between the governments of the United Kingdom and Australia in 1995, efforts were made to clean up the Maralinga site, being completed in 1995. Tonnes of soil and debris contaminated withplutoniumanduraniumwere buried in two trenches about 16 metres (52 ft) deep.[19]The effectiveness of the cleanup has been disputed on a number of occasions.[20][21]

In 2003 South Australian PremierMike Rannopened a new school costingA$2,000,000atOak Valley.The new school replaced two caravans with no running water or air-conditioning, a facility that had been described as the "worst school in Australia".[22]

In May 2004, following the passage of special legislation, Rann fulfilled a pledge he had made to Maralinga leaderArchie Bartonas Aboriginal Affairs Minister in 1991,[23]by handing back title to 21,000 square kilometres (8,100 sq mi) of land to the Maralinga Tjarutja andPila Ngurupeople. The land, 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) north-west of Adelaide and abutting theWestern Australiaborder, is now known asMamungari Conservation Park.It includes theSerpentine Lakesand was the largest land return since PremierJohn Bannon's hand over of Maralinga lands in 1984. The returned lands included the sacredOoldeaarea, which also included the site ofDaisy Bates' mission camp.[24]

In 2014, the last part of the land remaining in theWoomera Prohibited Area,known as "Section 400", was excised and returned to free access.[25]

Maralinga Tjarutja Council

[edit]The Maralinga Tjarutja Council is an incorporated body constituted by the traditional Yalata and Maralinga owners to administer the lands granted to them under theMaralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act 1984(SA).[26]The head office is inCeduna.

The Maralinga Tjarutja and the Pila Nguru (orSpinifex people) also jointly own and administer the 21,357.85-square-kilometre (8,246.31 sq mi)Mamungari Conservation Park,which area is contained in the area total for the council area.Emu Fieldis now part of the council area, too, while the 3,300-square-kilometre (1,300 sq mi)Maralingaarea is still a roughly square-shapedenclavewithin the council area.

The land surveyed and known as Section 400, 120 km2(46 sq mi) within the Taranaki Plumes,[27]was returned toTraditional Ownershipin 2007. This land includes the area of land occupied by the Maralinga Township and the areas in which atomic tests were carried out by the British and Australian governments.

The final part of the 1,782 km2(688 sq mi) former nuclear test site was returned in 2014.[28]

Documentary film

[edit]Maralinga Tjarutja,a May 2020 television documentary film directed byLarissa Behrendtand made byBlackfella FilmsforABC Television,tells the story of the people of Maralinga. It was deliberately broadcast around the same time that the drama seriesOperation Buffalo[29]was on, to give voice to the Indigenous people of the area and show how it disrupted their lives.[30][31]Screenhubgave it 4.5 stars, calling it an "excellent documentary".[32]The film shows the resilience of the Maralinga Tjarutja people, in which theelders"reveal a perspective ofdeep timeand an understanding of place that generates respect for the sacredness of both ", their ancestors having lived in the area for millennia.[33]Despite the callous disregard for their occupation of the land shown by the British and Australians involved in the testing, the people have continued to fight for their rights to look after thecontaminated land.[34]

The film, which was produced byDarren Dale,won the 2020AACTA Awardfor Best Direction in Nonfiction Television and the Silver Award for Documentary (Human Rights) at the 2021New York FestivalsTV & Film Awards.[35][36]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^Australian Bureau of Statistics(28 June 2022)."Maralinga Tjarutja (Local Government Area)".Australian Census 2021 QuickStats.Retrieved28 June2022.

- ^GoSA.

- ^School Context Statement 2015,p. 11.

- ^abMazel 2006,p. 161.

- ^Mazel 2006,p. 169.

- ^abPalmer 1990,p. 172.

- ^Palmer 1990,p. 173.

- ^Thurnwald 1951,pp. 385–386.

- ^Berndt 1974,p. 6.

- ^Hercus 1999,p. 3.

- ^abReece 2007,pp. 79–80.

- ^abcMazel 2006,p. 162.

- ^Palmer 1990,p. 181.

- ^abPalmer 1990,pp. 172–173.

- ^Cross 2005,p. 83.

- ^Cross 2005,p. 87.

- ^Mazel 2006,pp. 167–168.

- ^Palmer 1990,pp. 172–175–176.

- ^"Minister backs Maralinga clean-up".The Sydney Morning Herald.7 March 2003.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^"Maralinga".Australian Nuclear and Uranium Sites.23 July 2011.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^Ladd, Mike (23 March 2020)."The lesser known history of the Maralinga nuclear tests - and what it's like to stand at ground zero".ABC News (Radio National).Australian Broadcasting Corporation.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^ABC News 2003.

- ^The Age 2004.

- ^"Maralinga hand-over prompts celebration".The Age.25 August 2004.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^"Minister for Defence and Minister for Indigenous Affairs – Joint Media Release – Part of Maralinga Lands excised for traditional owners at Woomera".Australian Government Department of Defence.3 June 2014.Retrieved5 August2019.

- ^Maralinga Tjarutja 1984.

- ^Mazel 2006,p. 175.

- ^Sydney Morning Herald 2014.

- ^Mathieson, Craig (24 June 2020)."You won't be bored watching Operation Buffalo but you may be confused".The Sydney Morning Herald.Retrieved9 July2020.

- ^"When the dust settles, culture remains: Maralinga Tjarutja".indigenous.gov.au.Australian Government. 22 May 2020.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^"Maralinga Tjarutja".ABC iview.6 March 2018.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^Campbell, Mel (11 June 2020)."TV Review: Maralinga Tjarutja paints a full picture".screenhub Australia.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^Broderick, Mick (4 June 2020)."Sixty years on, two TV programs revisit Australia's nuclear history at Maralinga".The Conversation.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^Marsh, Walter (22 May 2020)."The story of Maralinga is much more than a period drama".The Adelaide Review.Retrieved13 September2020.

- ^"About: Staff: Darren Dale: Managing Director /Producer".Blackfella Films.Retrieved17 November2021.

- ^Knox, David (16 October 2021)."Aussies win at New York Festivals TV & Film Awards".TV Tonight.Retrieved17 November2021.

Sources

[edit]- Berndt, Ronald Murray(1941). "Tribal Migrations and Myths Centering on Ooldea, South Australia".Oceania.12(1): 1–20.doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1941.tb00343.x.

- Berndt, Ronald Murray(1974).Australian Aboriginal Religion.Brill Archive.ISBN9789004037281.

- Cross, Roger (2005) [First published 2003]."British Nuclear Tests and the Indigenous People of Australia".In Barnaby, Frank; Holdstock, Douglas (eds.).The British Nuclear Weapons Programme, 1952-2002.Routledge.pp. 75–88.ISBN978-1-135-76197-4.

- "Eyre Western SA Government region"(PDF).The Government of South Australia.Retrieved10 October2014.

- Hercus, Luise Anna (1999).A Grammar of the Wirangu Language from the West Coast of South Australia.Pacific linguistics.ISBN978-0-858-83505-4.

- "Homeland ceded to traditional owners".The Sydney Morning Herald.5 November 2014.

- "Maralinga hand-over prompts celebration".The Age.AAP. 25 August 2004.

- "Maralinga students welcome new school".ABC News.4 May 2003.

- "Maralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act 1984".Australasian Legal Information Institute. 1984.

- Mazel, Odette (2006)."Returning Parna Wiru: Restitution of the Maralinga Lands to the Traditional owners".In Langton, Marcia; Mazel, Odette; Palmer, Lisa; Shain, Kathryn; Tehan, Maureen (eds.).Settling with Indigenous People: Modern Treaty and Agreement-making in South Australia.Federation Press. pp. 159–180.ISBN978-1-862-87618-7.

- Palmer, Kingsley (1990)."Government policy and Aboriginal aspirations: self-management at Yalata".In Tonkinson, Robert; Howard, Michael (eds.).Going it Alone?: Prospects for Aboriginal Autonomy; Essays in Honourt of Ronald and Catherine Berndt.Aboriginal Studies Press. pp. 165–183.ISBN978-0-855-75566-9.

- Reece, Bob (2007).Daisy Bates: Grand Dame of the Desert.National Library of Australia.ISBN978-0-642-27654-4.

- "School Context Statement"(PDF).Department for Education and Child Development, Government of South Australia. August 2015. pp. 1–11. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 18 February 2017.Retrieved22 October2016.

- Thurnwald, Richard(1951).Des Menschengeistes Erwachen, Wachsen und Irren: Versuch einer Paläopsychologie von Naturvölkern mit Einschluss der archaischen Stufe und der allgemein menschlichen Züge.Duncker & Humblot.

- Yu, Sarah (1999).Ngapa Kunangkul: Living Water.University of Western Australia.CiteSeerX10.1.1.555.6295.

Further reading

[edit]- Pedler, Emma (22 August 2002)."Returning the Maralinga Tjarutja Lands".Statewide Afternoons, ABC South Australia.ABC.

External links

[edit]- Maralinga Tjarutja

- Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements (ATNS) project:

- Hansard extract from South Australian House of Assembly, 15 October 2003, of Second Reading Speech on co-management of the unnamed conservation park[permanent dead link]