Medicinal plants

Medicinal plants,also calledmedicinal herbs,have been discovered and used intraditional medicinepractices since prehistoric times.Plantssynthesize hundreds of chemical compounds for various functions, includingdefenseand protection againstinsects,fungi,diseases,andherbivorousmammals.[2]

The earliest historical records of herbs are found from theSumeriancivilization, where hundreds of medicinal plants includingopiumare listed on clay tablets,c. 3000 BC.TheEbers Papyrusfromancient Egypt,c. 1550 BC,describes over 850 plant medicines. The Greek physicianDioscorides,who worked in the Roman army, documented over 1000 recipes for medicines using over 600 medicinal plants inDe materia medica,c. 60 AD;this formed the basis ofpharmacopoeiasfor some 1500 years. Drug research sometimes makes use ofethnobotanyto search for pharmacologically active substances, and this approach has yielded hundreds of useful compounds. These include the common drugsaspirin,digoxin,quinine,andopium.The compounds found in plants are diverse, with most in four biochemical classes:alkaloids,glycosides,polyphenols,andterpenes.Few of these arescientifically confirmed as medicinesor used in conventional medicine.

Medicinal plants are widely used as folk medicine in non-industrialized societies, mainly because they are readily available and cheaper than modern medicines. The annual global export value of the thousands of types of plants with medicinal properties was estimated to be US$60 billion per year and growing at the rate of 6% per annum.[citation needed]In many countries, there is little regulation of traditional medicine, but theWorld Health Organizationcoordinates a network to encourage safe and rational use. The botanical herbal market has been criticized for being poorly regulated and containingplaceboandpseudoscienceproducts with no scientific research to support their medical claims.[3]Medicinal plants face both general threats, such asclimate changeandhabitat destruction,and the specific threat of over-collection to meet market demand.[3]

History

[edit]

Prehistoric times

[edit]Plants, including many now used asculinary herbsandspices,have been used as medicines, not necessarily effectively, from prehistoric times. Spices have been used partly to counterfood spoilagebacteria, especially in hot climates,[5][6]and especially in meat dishes that spoil more readily.[7]Angiosperms (flowering plants) were the original source of most plant medicines.[8]Human settlements are often surrounded by weeds used asherbal medicines,such asnettle,dandelionandchickweed.[9][10]Humans were not alone in using herbs as medicines: some animals such as non-humanprimates,monarch butterfliesandsheepingest medicinal plants when they are ill.[11]Plant samples from prehistoric burial sites are among the lines of evidence that Paleolithic peoples had knowledge of herbal medicine. For instance, a 60,000-year-old Neanderthal burial site, "Shanidar IV",in northern Iraq has yielded large amounts of pollen from eight plant species, seven of which are used now as herbal remedies.[12]Also, amushroomwas found in the personal effects ofÖtzi the Iceman,whose body was frozen in theÖtztal Alpsfor more than 5,000 years. The mushroom was probably used againstwhipworm.[13]

Ancient times

[edit]

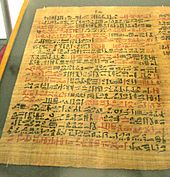

In ancientSumeria,hundreds of medicinal plants includingmyrrhandopiumare listed on clay tablets from around 3000 BC. Theancient EgyptianEbers Papyruslists over 800 plant medicines such asaloe,cannabis,castor bean,garlic,juniper,andmandrake.[14][15]

In antiquity, various cultures across Europe, including the Romans, Celts, and Nordic peoples, also practiced herbal medicine as a significant component of their healing traditions.

The Romans had a rich tradition of herbal medicine, drawing upon knowledge inherited from the Greeks and expanding upon it. Notable works include those of Pedanius Dioscorides, whose "De Materia Medica" served as a comprehensive guide to medicinal plants and remained influential for centuries.[16]Additionally, Pliny the Elder's "Naturalis Historia" contains valuable insights into Roman medical plant practices[17]

Among the Celtic peoples of ancient Europe, herbalism played a vital role in both medicine and spirituality. Druids, the religious leaders of the Celts, were reputed to possess deep knowledge of plants and their medicinal properties. Although written records are scarce, archaeological evidence, such as the discovery of medicinal plants at Celtic sites, provides insight into their herbal practices[18]

In the Nordic regions, including Scandinavia and parts of Germany, herbal medicine was also prevalent in ancient times. The Norse sagas and Eddic poetry often mention the use of herbs for healing purposes. Additionally, archaeological findings, such as the remains of medicinal plants in Viking-age graves, attest to the importance of herbal remedies in Nordic culture[19]

From ancient times to the present,Ayurvedic medicineas documented in theAtharva Veda,theRig Vedaand theSushruta Samhitahas used hundreds of herbs and spices, such asturmeric,which containscurcumin.[20]TheChinese pharmacopoeia,theShennong Ben Cao Jingrecords plant medicines such aschaulmoografor leprosy,ephedra,andhemp.[21]This was expanded in theTang dynastyYaoxing Lun.[22]In the fourth century BC,Aristotle's pupilTheophrastuswrote the first systematic botany text,Historia plantarum.[23]In around 60 AD, the Greek physicianPedanius Dioscorides,working for the Roman army, documented over 1000 recipes for medicines using over 600 medicinal plants inDe materia medica.The book remained the authoritative reference on herbalism for over 1500 years, into the seventeenth century.[4]

Middle Ages

[edit]

During the Middle Ages, herbalism continued to flourish across Europe, with distinct traditions emerging in various regions, often influenced by cultural, religious, indigenous, and geographical factors.

In theEarly Middle Ages,Benedictine monasteriespreserved medical knowledge inEurope,translating and copying classical texts and maintainingherb gardens.[24][25]Hildegard of BingenwroteCausae et Curae( "Causes and Cures" ) on medicine.[26]

In France, herbalism thrived alongside the practice of medieval medicine, which combined elements of Ancient Greek and Roman traditions. Catholic monastic orders played a significant role in preserving and expanding herbal knowledge. Manuscripts like the "Tractatus de Herbis" from the 15th century depict French herbal remedies and their uses.[27]Monasteries and convents served as centers of learning, where monks and nuns cultivated medicinal gardens. Likewise, in Italy, herbalism flourished with contribution Italian physicians like Matthaeus Platearius who compiled herbal manuscripts, such as the "Circa Instans," which served as practical guides for herbal remedies.[28]

In the Iberian Peninsula, the regions of the North remained independent during the period of Islamic occupation, and retained their traditional and indigenous medical practices. Galicia and Asturias, possessed a rich herbal heritage shaped by its Celtic and Roman influences. The Galician people were known for their strong connection to the land and nature and preserved botanical knowledge, with healers, known as "curandeiros" or "meigas," who relied on local plants for healing purposes[29]The Asturian landscape, characterized by lush forests and mountainous terrain, provided a rich source of medicinal herbs used in traditional healing practices, with "yerbatos," who possessed extensive knowledge of local plants and their medicinal properties[30]Barcelona, located in the Catalonia region of northeastern Spain, was a hub of cultural exchange during the Middle Ages, fostering the preservation and dissemination of medical knowledge. Catalan herbalists, known as "herbolarios," compiled manuscripts detailing the properties and uses of medicinal plants found in the region. The University of Barcelona, founded in 1450, played a pivotal role in advancing herbal medicine through its botanical gardens and academic pursuits.[31]

In Scotland and England, herbalism was deeply rooted in folk traditions and influenced by Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Norse practices. Herbal knowledge was passed down through generations, often by wise women known as "cunning folk." The "Physicians of Myddfai," a Welsh herbal manuscript from the 13th century, reflects the blending of Celtic and Christian beliefs in herbal medicine.[32]

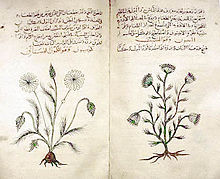

In theIslamic Golden Age,scholars translated many classical Greek texts including Dioscorides intoArabic,adding their own commentaries.[33] Herbalism flourished in the Islamic world, particularly inBaghdadand inAl-Andalus.Among many works on medicinal plants,Abulcasis(936–1013) ofCordobawroteThe Book of Simples,and Ibn al-Baitar (1197–1248) recorded hundreds of medicinal herbs such asAconitum,nux vomica,andtamarindin hisCorpus of Simples.[34]Avicennaincluded many plants in his 1025The Canon of Medicine.[35]Abu-Rayhan Biruni,[36]Ibn Zuhr,[37]Peter of Spain,andJohn of St Amandwrote furtherpharmacopoeias.[38]

Early Modern

[edit]

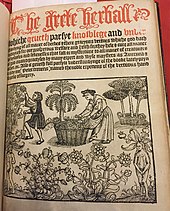

TheEarly Modernperiod saw the flourishing of illustratedherbalsacross Europe, starting with the 1526Grete Herball.John Gerardwrote his famousThe Herball or General History of Plantsin 1597, based onRembert Dodoens,andNicholas Culpeperpublished hisThe English Physician Enlarged.[39] Many new plant medicines arrived in Europe as products ofEarly Modern explorationand the resultingColumbian Exchange,in which livestock, crops and technologies were transferred between the Old World and the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. Medicinal herbs arriving in the Americas included garlic, ginger, and turmeric; coffee, tobacco and coca travelled in the other direction.[40][41] In Mexico, the sixteenth centuryBadianus Manuscriptdescribed medicinal plants available in Central America.[42]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]The place of plants in medicine was radically altered in the 19th century by the application ofchemical analysis.Alkaloidswere isolated from a succession of medicinal plants, starting withmorphinefrom thepoppyin 1806, and soon followed byipecacuanhaandstrychnosin 1817,quininefrom thecinchonatree, and then many others. As chemistry progressed, additional classes of potentially active substances were discovered in plants. Commercial extraction of purified alkaloids including morphine began atMerckin 1826.Synthesisof a substance first discovered in a medicinal plant began withsalicylic acidin 1853. Around the end of the 19th century, the mood of pharmacy turned against medicinal plants, asenzymesoften modified the active ingredients when whole plants were dried, and alkaloids and glycosides purified from plant material started to be preferred. Drug discovery from plants continued to be important through the 20th century and into the 21st, with important anti-cancer drugs fromyewandMadagascar periwinkle.[43][44][45]

Context

[edit]Medicinal plants are used with the intention of maintaining health, to be administered for a specific condition, or both, whether inmodern medicineor intraditional medicine.[3][46]TheFood and Agriculture Organizationestimated in 2002 that over 50,000 medicinal plants are used across the world.[47]TheRoyal Botanic Gardens, Kewmore conservatively estimated in 2016 that 17,810 plant species have a medicinal use, out of some 30,000 plants for which a use of any kind is documented.[48]

In modern medicine, around a quarter[a]of the drugs prescribed to patients are derived from medicinal plants, and they are rigorously tested.[46][49]In other systems of medicine, medicinal plants may constitute the majority of what are often informal attempted treatments, not tested scientifically.[50]TheWorld Health Organizationestimates, without reliable data, that some 80 percent of the world's population depends mainly on traditional medicine (including but not limited to plants); perhaps some two billion people are largely reliant on medicinal plants.[46][49]The use of plant-based materials including herbal or natural health products with supposed health benefits, is increasing in developed countries.[51]This brings attendant risks of toxicity and other effects on human health, despite the safe image of herbal remedies.[51]Herbal medicines have been in use since long before modern medicine existed; there was and often still is little or no knowledge of the pharmacological basis of their actions, if any, or of their safety. The World Health Organization formulated a policy on traditional medicine in 1991, and since then has published guidelines for them, with a series of monographs on widely used herbal medicines.[52][53]

Medicinal plants may provide three main kinds of benefit: health benefits to the people who consume them as medicines; financial benefits to people who harvest, process, and distribute them for sale; and society-wide benefits, such as job opportunities, taxation income, and a healthier labour force.[46]However, development of plants or extracts having potential medicinal uses is blunted by weak scientific evidence, poor practices in the process ofdrug development,and insufficient financing.[3][54]

Phytochemical basis

[edit]All plants produce chemical compounds which give them anevolutionaryadvantage, such asdefending against herbivoresor, in the example ofsalicylic acid,as ahormonein plant defenses.[55][56]These phytochemicals have potential for use as drugs, and the content and known pharmacological activity of these substances in medicinal plants is the scientific basis for their use in modern medicine, if scientifically confirmed.[3]For instance, daffodils (Narcissus) contain nine groups of alkaloids includinggalantamine,licensed for use againstAlzheimer's disease.The alkaloids are bitter-tasting and toxic, and concentrated in the parts of the plant such as the stem most likely to be eaten by herbivores; they may also protect againstparasites.[57][58][59]

Modern knowledge of medicinal plants is being systematised in the Medicinal Plant Transcriptomics Database, which by 2011 provided a sequence reference for thetranscriptomeof some thirty species.[60]Major classes of plantphytochemicalsare described below, with examples of plants that contain them.[8][53][61][62][63]

Alkaloids

[edit]Alkaloidsare bitter-tasting chemicals, very widespread in nature, and often toxic, found in many medicinal plants.[64]There are several classes with different modes of action as drugs, both recreational and pharmaceutical. Medicines of different classes includeatropine,scopolamine,andhyoscyamine(all fromnightshade),[65]the traditional medicineberberine(from plants such asBerberisandMahonia),[b]caffeine(Coffea),cocaine(Coca),ephedrine(Ephedra),morphine(opium poppy),nicotine(tobacco),[c]reserpine(Rauvolfia serpentina),quinidineandquinine(Cinchona),vincamine(Vinca minor), andvincristine(Catharanthus roseus).[63][68]

-

The alkaloidnicotinefromtobaccobinds directly to the body'sNicotinic acetylcholine receptors,accounting for its pharmacological effects.[69]

-

Deadly nightshade,Atropa belladonna,yieldstropane alkaloidsincludingatropine,scopolamineandhyoscyamine.[65]

Glycosides

[edit]Anthraquinoneglycosidesare found in medicinal plants such asrhubarb,cascara,andAlexandrian senna.[70][71]Plant-basedlaxativesmade from such plants includesenna,[72]rhubarb[73]andAloe.[63]

Thecardiac glycosidesare powerful drugs from medicinal plants includingfoxgloveandlily of the valley.They includedigoxinanddigitoxinwhich support the beating of the heart, and act asdiuretics.[55]

-

Thefoxglove,Digitalis purpurea,containsdigoxin,acardiac glycoside.The plant was used on heart conditions long before the glycoside was identified.[55][74]

Polyphenols

[edit]Polyphenolsof several classes are widespread in plants, having diverse roles in defenses against plant diseases and predators.[55]They include hormone-mimickingphytoestrogensand astringenttannins.[63][75]Plants containing phytoestrogens have been administered for centuries forgynecologicaldisorders, such as fertility, menstrual, and menopausal problems.[76]Among these plants arePuerariamirifica,[77]kudzu,[78]angelica,[79]fennel,andanise.[80]

Many polyphenolic extracts, such as fromgrape seeds,olivesormaritime pine bark,are sold asdietary supplementsandcosmeticswithout proof or legalhealth claimsfor medicinal effects.[81]InAyurveda,the astringent rind of thepomegranate,containing polyphenols calledpunicalagins,is used as a medicine, with no scientific proof of efficacy.[81][82]

-

Angelica,containingphytoestrogens,has long been used for gynaecological disorders.

Terpenes

[edit]Terpenesandterpenoidsof many kinds are found in a variety of medicinal plants,[84]and inresinousplants such as theconifers.They are strongly aromatic and serve to repel herbivores. Their scent makes them useful inessential oils,whether forperfumessuch asroseandlavender,or foraromatherapy.[63][85][86]Some have medicinal uses: for example,thymolis an antiseptic and was once used as avermifuge(anti-worm medicine).[87]

-

Theessential oilofcommon thyme(Thymus vulgaris), contains themonoterpenethymol,anantisepticandantifungal.[87]

In practice

[edit]

Cultivation

[edit]Medicinal plants demand intensive management. Different species each require their own distinct conditions of cultivation. TheWorld Health Organizationrecommends the use ofrotationto minimise problems with pests and plant diseases. Cultivation may be traditional or may make use ofconservation agriculturepractices to maintain organic matter in the soil and to conserve water, for example withno-till farmingsystems.[88]In many medicinal and aromatic plants, plant characteristics vary widely with soil type and cropping strategy, so care is required to obtain satisfactory yields.[89]

Preparation

[edit]

Medicinal plants are often tough and fibrous, requiring some form of preparation to make them convenient to administer. According to the Institute for Traditional Medicine, common methods for the preparation of herbal medicines includedecoction,powdering, and extraction with alcohol, in each case yielding a mixture of substances. Decoction involves crushing and then boiling the plant material in water to produce a liquid extract that can be taken orally or applied topically.[90]Powdering involves drying the plant material and then crushing it to yield a powder that can be compressed intotablets.Alcohol extraction involves soaking the plant material in cold wine or distilled spirit to form atincture.[91]

Traditionalpoulticeswere made by boiling medicinal plants, wrapping them in a cloth, and applying the resulting parcel externally to the affected part of the body.[92]

When modern medicine has identified a drug in a medicinal plant, commercial quantities of the drug may either besynthesisedor extracted from plant material, yielding a pure chemical.[43]Extraction can be practical when the compound in question is complex.[93]

Usage

[edit]

Plant medicines are in wide use around the world.[94]In most of the developing world, especially in rural areas, localtraditional medicine,including herbalism, is the only source of health care for people, while in thedeveloped world,alternative medicineincluding use ofdietary supplementsis marketed aggressively using the claims of traditional medicine. As of 2015, most products made from medicinal plants had not been tested for their safety and efficacy, and products that were marketed in developed economies and provided in the undeveloped world by traditional healers were of uneven quality, sometimes containing dangerous contaminants.[95]Traditional Chinese medicinemakes use of a wide variety of plants, among other materials and techniques.[96]Researchers fromKew Gardensfound 104 species used fordiabetesin Central America, of which seven had been identified in at least three separate studies.[97][98]TheYanomamiof the Brazilian Amazon, assisted by researchers, have described 101 plant species used for traditional medicines.[99][100]

Drugs derived from plants including opiates, cocaine and cannabis have both medical andrecreational uses.Different countries have at various times madeuse of illegal drugs,partly on the basis of the risks involved in takingpsychoactive drugs.[101]

Effectiveness

[edit]

Plant medicines have often not been tested systematically, but have come into use informally over the centuries. By 2007, clinical trials had demonstrated potentially useful activity in nearly 16% of herbal extracts; there was limited in vitro or in vivo evidence for roughly half the extracts; there was only phytochemical evidence for around 20%; 0.5% were allergenic or toxic; and some 12% had basically never been studied scientifically.[53]Cancer Research UK caution that there is no reliable evidence for the effectiveness of herbal remedies for cancer.[102]

A 2012phylogeneticstudy built a family tree down togenuslevel using 20,000 species to compare the medicinal plants of three regions, Nepal, New Zealand and the Cape of South Africa. It discovered that the species used traditionally to treat the same types of condition belonged to the same groups of plants in all three regions, giving a "strong phylogenetic signal".[103]Since many plants that yield pharmaceutical drugs belong to just these groups, and the groups were independently used in three different world regions, the results were taken to mean 1) that these plant groups do have potential for medicinal efficacy, 2) that undefined pharmacological activity is associated with use in traditional medicine, and 3) that the use of a phylogenetic groups for possible plant medicines in one region may predict their use in the other regions.[103]

Regulation

[edit]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has been coordinating a network called the International Regulatory Cooperation for Herbal Medicines to try to improve the quality of medical products made from medicinal plants and the claims made for them.[104]In 2015, only around 20% of countries had well-functioning regulatory agencies, while 30% had none, and around half had limited regulatory capacity.[95]In India, whereAyurvedahas been practised for centuries, herbal remedies are the responsibility of a government department,AYUSH,under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare.[105]

WHO has set out a strategy for traditional medicines[106]with four objectives: to integrate them as policy into national healthcare systems; to provide knowledge and guidance on their safety, efficacy, and quality; to increase their availability and affordability; and to promote their rational, therapeutically sound usage.[106]WHO notes in the strategy that countries are experiencing seven challenges to such implementation, namely in developing and enforcing policy; in integration; in safety and quality, especially in assessment of products and qualification of practitioners; in controlling advertising; in research and development; in education and training; and in the sharing of information.[106]

Drug discovery

[edit]

Thepharmaceutical industryhas roots in theapothecaryshops of Europe in the 1800s, where pharmacists provided local traditional medicines to customers, which included extracts like morphine, quinine, and strychnine.[107]Therapeutically important drugs likecamptothecin(fromCamptotheca acuminata,used in traditional Chinese medicine) andtaxol(from the Pacific yew,Taxus brevifolia) were derived from medicinal plants.[108][43]TheVinca alkaloidsvincristineandvinblastine,used as anti-cancer drugs, were discovered in the 1950s from the Madagascar periwinkle,Catharanthus roseus.[109]

Hundreds of compounds have been identified usingethnobotany,investigating plants used by indigenous peoples for possible medical applications.[110]Some important phytochemicals, includingcurcumin,epigallocatechin gallate,genisteinandresveratrolarepan-assay interference compounds,meaning thatin vitrostudies of their activity often provide unreliable data. As a result, phytochemicals have frequently proven unsuitable as the lead substances indrug discovery.[111][112]In the United States over the period 1999 to 2012, despite several hundred applications fornew drug status,only twobotanical drugcandidates had sufficient evidence of medicinal value to be approved by theFood and Drug Administration.[3]

The pharmaceutical industry has remained interested in mining traditional uses of medicinal plants in its drug discovery efforts.[43]Of the 1073 small-molecule drugs approved in the period 1981 to 2010, over half were either directly derived from or inspired by natural substances.[43][113]Among cancer treatments, of 185 small-molecule drugs approved in the period from 1981 to 2019, 65% were derived from or inspired by natural substances.[114]

Safety

[edit]

Plant medicines can cause adverse effects and even death, whether by side-effects of their active substances, by adulteration or contamination, by overdose, or by inappropriate prescription. Many such effects are known, while others remain to be explored scientifically. There is no reason to presume that because a product comes from nature it must be safe: the existence of powerful natural poisons like atropine and nicotine shows this to be untrue. Further, the high standards applied to conventional medicines do not always apply to plant medicines, and dose can vary widely depending on the growth conditions of plants: older plants may be much more toxic than young ones, for instance.[116][117][118][119][120][121]

Plant extracts may interact with conventional drugs, both because they may provide an increased dose of similar compounds, and because some phytochemicals interfere with the body's systems that metabolise drugs in the liver including thecytochrome P450system, making the drugs last longer in the body and have a cumulative effect.[122]Plant medicines can be dangerous during pregnancy.[123]Since plants may contain many different substances, plant extracts may have complex effects on the human body.[5]

Quality, advertising, and labelling

[edit]Herbal medicine anddietary supplementproducts have been criticized as not having sufficient standards or scientific evidence to confirm their contents, safety, and presumed efficacy.[124][125][126][127]Companies often make false claims about their herbal products promising health benefits that aren't backed by evidence to generate more sales. The market for dietary supplements and nutraceuticals grew by 5% during the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the United States taking action to stop the deceptive marketing of herbal products to combat the virus.[128][129]

Threats

[edit]Where medicinal plants are harvested from the wild rather than cultivated, they are subject to both general and specific threats. General threats includeclimate changeandhabitat lossto development and agriculture. A specific threat is over-collection to meet rising demand for medicines.[130]A case in point was the pressure on wild populations of the Pacific yew soon after news of taxol's effectiveness became public.[43]The threat from over-collection could be addressed by cultivation of some medicinal plants, or by a system of certification to make wild harvesting sustainable.[130]A report in 2020 by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew identifies 723 medicinal plants as being at risk of extinction, caused partly by over-collection.[131][114]

See also

[edit]- Australian Phytochemical Survey

- Ethnomedicine

- European Directive on Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products

- Plant Resources of Tropical Africa

Notes

[edit]- ^Farnsworth states that this figure was based on prescriptions from American community pharmacies between 1959 and 1980.[49]

- ^Berberine is the main active component of an ancient Chinese herbCoptis chinensisFrench, which has been administered for what Yin and colleagues state is "diabetes"for thousands of years, although with no sound evidence of efficacy.[66]

- ^Tobacco has "probably been responsible for more deaths than any other herb", but it was used as a medicine in the societies encountered by Columbus and was considered apanaceain Europe. It is no longer accepted as medicinal.[67]

References

[edit]- ^Lichterman BL (2004)."Aspirin: The Story of a Wonder Drug".British Medical Journal.329(7479): 1408.doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7479.1408.PMC535471.

- ^Gershenzon J, Ullah C (January 2022)."Plants protect themselves from herbivores by optimizing the distribution of chemical defenses".Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.119(4).Bibcode:2022PNAS..11920277G.doi:10.1073/pnas.2120277119.PMC8794845.PMID35084361.

- ^abcdefAhn K (2017)."The worldwide trend of using botanical drugs and strategies for developing global drugs".BMB Reports.50(3): 111–116.doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.3.221.PMC5422022.PMID27998396.

- ^abCollins M (2000).Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Traditions.University of Toronto Press.p. 32.ISBN978-0-8020-8313-5.

- ^abTapsell, L. C., Hemphill, I., Cobiac, L., et al. (August 2006)."Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future".Med. J. Aust.185(4 Suppl): S4–24.doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00548.x.hdl:2440/22802.PMID17022438.S2CID9769230.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-10-31.Retrieved2020-08-27.

- ^Billing J, Sherman PW (March 1998). "Antimicrobial functions of spices: why some like it hot".Quarterly Review of Biology.73(1): 3–49.doi:10.1086/420058.PMID9586227.S2CID22420170.

- ^Sherman PW, Hash GA (May 2001). "Why vegetable recipes are not very spicy".Evolution and Human Behavior.22(3): 147–163.doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(00)00068-4.PMID11384883.

- ^ab"Angiosperms: Division Magnoliophyta: General Features".Encyclopædia Britannica(volume 13, 15th edition).1993. p. 609.

- ^Stepp JR (June 2004). "The role of weeds as sources of pharmaceuticals".Journal of Ethnopharmacology.92(2–3): 163–166.doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.002.PMID15137997.

- ^Stepp JR, Moerman DE (April 2001). "The importance of weeds in ethnopharmacology".Journal of Ethnopharmacology.75(1): 19–23.doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00385-8.PMID11282438.

- ^Sumner, Judith (2000).The Natural History of Medicinal Plants.Timber Press.p. 16.ISBN978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^Solecki RS (November 1975). "Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq".Science.190(4217): 880–881.Bibcode:1975Sci...190..880S.doi:10.1126/science.190.4217.880.S2CID71625677.

- ^Capasso, L. (December 1998)."5300 years ago, the Ice Man used natural laxatives and antibiotics".Lancet.352(9143): 1864.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79939-6.PMID9851424.S2CID40027370.

- ^abSumner J (2000).The Natural History of Medicinal Plants.Timber Press.p. 17.ISBN978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^Petrovska 2012,pp. 1–5.

- ^Osbaldeston, Tess Anne. Dioscorides: De Materia Medica. Olms-Weidmann, 2000

- ^Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Harvard University Press, 1938-1963

- ^Ross, Anne. Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition. Constable, 1967

- ^Wills, Tarrin. "Herbal Medicine in the Viking Age." Viking Magazine, vol. 80, no. 3, 2017, pp. 22-27.

- ^Dwivedi G, Dwivedi S (2007).History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence(PDF).National Informatics Centre.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 10 October 2008.Retrieved8 October2008.

- ^Sumner J (2000).The Natural History of Medicinal Plants.Timber Press.p. 18.ISBN978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^Wu JN (2005).An Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica.Oxford University Press.p. 6.ISBN978-0-19-514017-0.

- ^Grene M (2004).The philosophy of biology: an episodic history.Cambridge University Press.p. 11.ISBN978-0-521-64380-1.

- ^Arsdall AV (2002).Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine.Psychology Press. pp. 70–71.ISBN978-0-415-93849-5.

- ^Mills FA (2000)."Botany".In Johnston, William M. (ed.).Encyclopedia of Monasticism: M-Z.Taylor & Francis.p. 179.ISBN978-1-57958-090-2.

- ^Ramos-e-Silva Marcia (1999). "Saint Hildegard Von Bingen (1098–1179)" The Light Of Her People And Of Her Time "".International Journal of Dermatology.38(4): 315–320.doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00617.x.PMID10321953.S2CID13404562.

- ^Givens, Jean A. "The Tractatus de Herbis: A Thirteenth-Century Herbal." The British Library, 1982.

- ^Givens, Jean A. "The Tractatus de Herbis: A Thirteenth-Century Herbal." The British Library, 1982

- ^Fernández, Marta. "The Herbalist in Galicia." Ethnobotany Research and Applications, vol. 8, 2010, pp. 263–277.

- ^Díaz-Puente, José Manuel, et al. "Traditional Medicine in Asturias (Northern Spain)." Journal of Ethnopharmacology, vol. 45, no. 2, 1995, pp. 67–74.

- ^Vallès, Joan. "Botany and Medicine in Medieval Barcelona." Dynamis, vol. 19, 1999, pp. 349–377.

- ^Lloyd, Robert, editor. "The Physicians of Myddfai." The Welsh MSS. Society, 1861.

- ^Castleman M (2001).The New Healing Herbs.Rodale. p.15.ISBN978-1-57954-304-4.;Collins M (2000).Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Traditions.University of Toronto Press.p. 115.ISBN978-0-8020-8313-5.;"Pharmaceutics and Alchemy".US National Library of Medicine.Archivedfrom the original on 5 January 2017.Retrieved26 January2017.;Fahd T.Botany and agriculture.p. 815.,inRashed R, Morelon R (1996).Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science: Astronomy-Theoretical and applied, v.2 Mathematics and the physical sciences; v.3 Technology, alchemy and life sciences.Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-02063-3.

- ^Castleman M (2001).The New Healing Herbs.Rodale. p.15.ISBN978-1-57954-304-4.

- ^Jacquart D (2008). "Islamic Pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Theories and Substances".European Review.16(2): 219–227 [223].doi:10.1017/S1062798708000215.

- ^Kujundzić, E., Masić, I. (1999). "[Al-Biruni--a universal scientist]".Med. Arh.(in Croatian).53(2): 117–120.PMID10386051.

- ^Krek M (1979). "The Enigma of the First Arabic Book Printed from Movable Type".Journal of Near Eastern Studies.38(3): 203–212.doi:10.1086/372742.S2CID162374182.

- ^Brater, D. Craig, Daly, Walter J. (2000). "Clinical pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Principles that presage the 21st century".Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics.67(5): 447–450 [448–449].doi:10.1067/mcp.2000.106465.PMID10824622.S2CID45980791.

- ^abSinger C(1923). "Herbals".The Edinburgh Review.237:95–112.

- ^Nunn N, Qian N (2010). "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas".Journal of Economic Perspectives.24(2): 163–188.CiteSeerX10.1.1.232.9242.doi:10.1257/jep.24.2.163.JSTOR25703506.

- ^Heywood VH (2012)."The role of New World biodiversity in the transformation of Mediterranean landscapes and culture"(PDF).Bocconea.24:69–93. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2017-02-27.Retrieved2017-02-26.

- ^Gimmel Millie (2008). "Reading Medicine In The Codex De La Cruz Badiano".Journal of the History of Ideas.69(2): 169–192.doi:10.1353/jhi.2008.0017.PMID19127831.S2CID46457797.

- ^abcdefAtanasov AG, Waltenberger B, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, Linder T, Wawrosch C, Uhrin P, Temml V, Wang L, Schwaiger S, Heiss EH, Rollinger JM, Schuster D, Breuss JM, Bochkov V, Mihovilovic MD, Kopp B, Bauer R, Dirsch VM, Stuppner H (December 2015)."Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review".Biotechnology Advances.33(8): 1582–1614.doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001.PMC4748402.PMID26281720.

- ^Petrovska BB (2012)."Historical review of medicinal plants' usage".Pharmacognosy Reviews.6(11): 1–5.doi:10.4103/0973-7847.95849.PMC3358962.PMID22654398.

- ^Price, J. R., Lamberton, J. A., Culvenor, C.C.J (1992),"The Australian Phytochemical Survey: historical aspects of the CSIRO search for new drugs in Australian plants. Historical Records of Australian Science, 9(4), 335–356",Historical Records of Australian Science,9(4), Australian Academy of Science: 335–356,doi:10.1071/hr9930940335,archivedfrom the original on 2022-01-21,retrieved2022-04-02

- ^abcdSmith-Hall, C., Larsen, H.O., Pouliot, M. (2012)."People, plants and health: a conceptual framework for assessing changes in medicinal plant consumption".J Ethnobiol Ethnomed.8:43.doi:10.1186/1746-4269-8-43.PMC3549945.PMID23148504.

- ^Schippmann U, Leaman DJ, Cunningham AB (12 October 2002)."Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity: Global Trends and Issues 2. Some Figures to start with..."Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Satellite event on the occasion of the Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome, 12–13 October 2002. Inter-Departmental Working Group on Biological Diversity for Food and Agriculture. Rome.Food and Agriculture Organization.Archivedfrom the original on 24 July 2017.Retrieved25 September2017.

- ^"State of the World's Plants Report - 2016"(PDF).Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2016. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 19 September 2017.Retrieved25 September2017.

- ^abcFarnsworth NR, Akerele O, Bingel AS, Soejarto DD, Guo Z (1985)."Medicinal plants in therapy".Bulletin of the World Health Organization.63(6): 965–981.PMC2536466.PMID3879679.

- ^Tilburt JC, Kaptchuk TJ (August 2008)."Herbal medicine research and global health: an ethical analysis".Bulletin of the World Health Organization.86(8): 577–656.doi:10.2471/BLT.07.042820.PMC2649468.PMID18797616.Archived fromthe originalon January 24, 2010.Retrieved22 September2017.

- ^abEkor M (2013)."The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety".Frontiers in Pharmacology.4(3): 202–4.doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00177.PMC3887317.PMID24454289.

- ^Singh A (2016).Regulatory and Pharmacological Basis of Ayurvedic Formulations.CRC Press. pp. 4–5.ISBN978-1-4987-5096-7.

- ^abcCravotto G, Boffa L, Genzini L, Garella D (February 2010)."Phytotherapeutics: an evaluation of the potential of 1000 plants".Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics.35(1): 11–48.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01096.x.PMID20175810.S2CID29427595.

- ^Berida T, Adekunle Y, Dada-Adegbola H, Kdimy A, Roy S, Sarker S (May 2024)."Plant antibacterials: The challenges and opportunities".Heliyon.10(10): e31145.doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31145.PMC11128932.PMID38803958.

- ^abcde"Active Plant Ingredients Used for Medicinal Purposes".United States Department of Agriculture.Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2018.Retrieved18 February2017.

Below are several examples of active plant ingredients that provide medicinal plant uses for humans.

- ^Hayat, S., Ahmad, A. (2007).Salicylic Acid – A Plant Hormone.Springer Science and Business Media.ISBN978-1-4020-5183-8.

- ^Bastida J, Lavilla R, Viladomat FV (2006). "Chemical and Biological Aspects ofNarcissusAlkaloids ". In Cordell GA (ed.).The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology.Vol. 63. pp. 87–179.doi:10.1016/S1099-4831(06)63003-4.ISBN978-0-12-469563-4.PMC7118783.PMID17133715.

- ^"Galantamine".Drugs.com. 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 14 October 2018.Retrieved17 March2018.

- ^Birks J (2006). Birks JS (ed.)."Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease".The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.2016(1): CD005593.doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005593.PMC9006343.PMID16437532.

- ^Soejarto DD (1 March 2011)."Transcriptome Characterization, Sequencing, And Assembly Of Medicinal Plants Relevant To Human Health".University of Illinois at Chicago.Archivedfrom the original on 20 April 2017.Retrieved26 January2017.

- ^Meskin, Mark S. (2002).Phytochemicals in Nutrition and Health.CRC Press. p. 123.ISBN978-1-58716-083-7.

- ^Springbob, Karen, Kutchan, Toni M. (2009)."Introduction to the different classes of natural products".In Lanzotti, Virginia (ed.).Plant-Derived Natural Products: Synthesis, Function, and Application.Springer. p. 3.ISBN978-0-387-85497-7.

- ^abcdefElumalai A, Eswariah MC (2012)."Herbalism - A Review"(PDF).International Journal of Phytotherapy.2(2): 96–105. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2017-02-17.Retrieved2017-02-17.

- ^Aniszewski, Tadeusz (2007).Alkaloids – secrets of life.Amsterdam:Elsevier.p. 182.ISBN978-0-444-52736-3.

- ^ab"Atropa Belladonna"(PDF).The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. 1998.Archived(PDF)from the original on 17 April 2018.Retrieved26 February2017.

- ^Yin J, Xing H, Ye J (May 2008)."Efficacy of Berberine in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes".Metabolism.57(5): 712–717.doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2008.01.013.PMC2410097.PMID18442638.

- ^Charlton A (June 2004)."Medicinal uses of tobacco in history".Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.97(6): 292–296.doi:10.1177/014107680409700614.PMC1079499.PMID15173337.

- ^Gremigni P, et al. (2003). "The interaction of phosphorus and potassium with seed alkaloid concentrations, yield and mineral content in narrow-leafed lupin (Lupinus angustifolius L.)".Plant and Soil.253(2): 413–427.doi:10.1023/A:1024828131581.JSTOR24121197.S2CID25434984.

- ^"Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Introduction".IUPHAR Database.International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology.Archivedfrom the original on 29 June 2017.Retrieved26 February2017.

- ^Wang, Zhe, Ma, Pei, He, Chunnian, Peng, Yong, Xiao, Peigen (2013)."Evaluation of the content variation of anthraquinone glycosides in rhubarb by UPLC-PDA".Chemistry Central Journal.7(1): 43–56.doi:10.1186/1752-153X-7-170.PMC3854541.PMID24160332.

- ^Chan K, Lin T (2009).Treatments used in complementary and alternative medicine.Side Effects of Drugs Annual. Vol. 31. pp. 745–756.doi:10.1016/S0378-6080(09)03148-1.ISBN978-0-444-53294-7.

- ^abHietala, P., Marvola, M., Parviainen, T., Lainonen, H. (August 1987). "Laxative potency and acute toxicity of some anthraquinone derivatives, senna extracts and fractions of senna extracts".Pharmacology & Toxicology.61(2): 153–6.doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1987.tb01794.x.PMID3671329.

- ^Akolkar, Praful (2012-12-27)."Pharmacognosy of Rhubarb".PharmaXChange.info.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-06-26.Retrieved2017-02-02.

- ^"Digitalis purpurea. Cardiac Glycoside".Texas A&M University.Archivedfrom the original on 2 July 2018.Retrieved26 February2017.

The man credited with the introduction of digitalis into the practice of medicine wasWilliam Withering.

- ^Da Silva C, et al. (2013)."The High Polyphenol Content of Grapevine Cultivar Tannat Berries Is Conferred Primarily by Genes That Are Not Shared with the Reference Genome".The Plant Cell.25(12): 4777–4788.doi:10.1105/tpc.113.118810.JSTOR43190600.PMC3903987.PMID24319081.

- ^Muller-Schwarze D (2006).Chemical Ecology of Vertebrates.Cambridge University Press. p. 287.ISBN978-0-521-36377-8.

- ^Lee, Y. S., Park J. S., Cho S. D., Son J. K., Cherdshewasart W., Kang K. S. (Dec 2002)."Requirement of metabolic activation for estrogenic activity of Pueraria mirifica".Journal of Veterinary Science.3(4): 273–277.CiteSeerX10.1.1.617.1507.doi:10.4142/jvs.2002.3.4.273.PMID12819377.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-04-19.Retrieved2019-04-19.

- ^Delmonte, P., Rader, J. I. (2006)."Analysis of isoflavones in foods and dietary supplements".Journal of AOAC International.89(4): 1138–46.doi:10.1093/jaoac/89.4.1138.PMID16915857.

- ^Brown D, Walton NJ (1999).Chemicals from Plants: Perspectives on Plant Secondary Products.World Scientific Publishing. pp. 21, 141.ISBN978-981-02-2773-9.

- ^Albert-Puleo, M. (Dec 1980). "Fennel and anise as estrogenic agents".Journal of Ethnopharmacology.2(4): 337–44.doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(80)81015-4.PMID6999244.

- ^abEuropean Food Safety Authority (2010)."Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to various food(s)/food constituent(s) and protection of cells from premature aging, antioxidant activity, antioxidant content and antioxidant properties, and protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061".EFSA Journal.8(2): 1489.doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1489.

- ^Jindal, K. K., Sharma, R. C. (2004).Recent trends in horticulture in the Himalayas.Indus Publishing.ISBN978-81-7387-162-7.

- ^Turner, J. V., Agatonovic-Kustrin, S., Glass, B. D. (August 2007). "Molecular aspects of phytoestrogen selective binding at estrogen receptors".Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences.96(8): 1879–85.doi:10.1002/jps.20987.PMID17518366.

- ^Wiart C (2014). "Terpenes".Lead Compounds from Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases.Elsevier Inc. pp. 189–284.doi:10.1016/C2011-0-09611-4.ISBN978-0-12-398373-2.

- ^Tchen TT (1965). "The Biosynthesis of Steroids, Terpenes and Acetogenins".American Scientist.53(4): 499A–500A.JSTOR27836252.

- ^Singsaas EL (2000)."Terpenes and the Thermotolerance of Photosynthesis".New Phytologist.146(1): 1–2.doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00626.x.JSTOR2588737.

- ^abc"Thymol (CID=6989)".NIH.Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2018.Retrieved26 February2017.

THYMOL is a phenol obtained from thyme oil or other volatile oils used as a stabilizer in pharmaceutical preparations, and as an antiseptic (antibacterial or antifungal) agent. It was formerly used as a vermifuge.

- ^"WHO Guidelines on Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP) for Medicinal Plants".World Health Organization. 2003. Archived fromthe originalon October 20, 2009.Retrieved26 February2017.

- ^Carrubba, A., Scalenghe, R. (2012). "Scent of Mare Nostrum ― Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs) in Mediterranean soils".Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture.92(6): 1150–1170.doi:10.1002/jsfa.5630.PMID22419102.

- ^Yang Y (2010)."Theories and concepts in the composition of Chinese herbal formulas".Chinese Herbal Formulas.Elsevier Ltd.: 1–34.doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-3132-8.00006-2.ISBN9780702031328.Retrieved18 April2020.

- ^Dharmananda S (May 1997)."The Methods of Preparation of Herb Formulas: Decoctions, Dried Decoctions, Powders, Pills, Tablets, and Tinctures".Institute of Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-10-04.Retrieved2017-09-27.

- ^Mount T (20 April 2015)."9 weird medieval medicines".British Broadcasting Corporation.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2017.Retrieved27 September2017.

- ^Pezzuto JM (January 1997). "Plant-derived anticancer agents".Biochemical Pharmacology.53(2): 121–133.doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(96)00654-5.PMID9037244.

- ^"Traditional Medicine. Fact Sheet No. 134".World Health Organization. May 2003. Archived fromthe originalon 27 July 2008.Retrieved26 February2017.

- ^abChan M (19 August 2015)."WHO Director-General addresses traditional medicine forum".WHO. Archived fromthe originalon August 22, 2015.

- ^"Traditional Chinese Medicine: In Depth (D428)".NIH. April 2009.Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2017.Retrieved26 February2017.

- ^Giovannini P."Managing diabetes with medicinal plants".Kew Gardens.Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2017.Retrieved3 October2017.

- ^Giovannini P, Howes MJ, Edwards SE (2016)."Medicinal plants used in the traditional management of diabetes and its sequelae in Central America: A review".Journal of Ethnopharmacology.184:58–71.doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.02.034.PMID26924564.S2CID22639191.Archivedfrom the original on 2022-06-07.Retrieved2020-08-27.

- ^Milliken W (2015)."Medicinal knowledge in the Amazon".Kew Gardens.Archivedfrom the original on 2017-10-03.Retrieved2017-10-03.

- ^Yanomami, M. I., Yanomami, E., Albert, B., Milliken, W, Coelho, V. (2014).Hwërɨ mamotima thëpë ã oni. Manual dos remedios tradicionais Yanomami[Manual of Traditional Yanomami Medicines]. São Paulo: Hutukara/Instituto Socioambiental.

- ^"Scoring drugs. A new study suggests alcohol is more harmful than heroin or crack".The Economist.2 November 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2018.Retrieved26 February2017.

"Drug harms in the UK: a multi-criteria decision analysis", by David Nutt, Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips, on behalf of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs.The Lancet.

- ^"Herbal medicine".Cancer Research UK.Archivedfrom the original on 29 May 2019.Retrieved7 July2019.

There is no reliable evidence from human studies that herbal remedies can treat, prevent or cure any type of cancer. Some clinical trials seem to show that certain Chinese herbs may help people to live longer, might reduce side effects, and help to prevent cancer from coming back. This is especially when combined with conventional treatment.

- ^abSaslis-Lagoudakis CH, Savolainen V, Williamson EM, Forest F, Wagstaff SJ, Baral SR, Watson MF, Pendry CA, Hawkins JA (2012)."Phylogenies reveal predictive power of traditional medicine in bioprospecting".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.109(39): 15835–40.Bibcode:2012PNAS..10915835S.doi:10.1073/pnas.1202242109.PMC3465383.PMID22984175.

- ^"International Regulatory Cooperation for Herbal Medicines (IRCH)".World Health Organization. Archived fromthe originalon September 1, 2013.Retrieved2 October2017.

- ^Kala CP, Sajwan BS (2007). "Revitalizing Indian systems of herbal medicine by the National Medicinal Plants Board through institutional networking and capacity building".Current Science.93(6): 797–806.JSTOR24099124.

- ^abcWorld Health Organization (2013).WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023(PDF).World Health Organization.ISBN978-92-4-150609-0.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2017-11-18.Retrieved2017-10-03.

- ^"Emergence of Pharmaceutical Science and Industry: 1870-1930".Chemical & Engineering News.Vol. 83, no. 25. 20 June 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 10 November 2018.Retrieved2 October2017.

- ^Heinrich M, Bremner P (March 2006). "Ethnobotany and ethnopharmacy--their role for anti-cancer drug development".Current Drug Targets.7(3): 239–245.doi:10.2174/138945006776054988.PMID16515525.

- ^Moudi M, Go R, Yien CY, Nazre M (November 2013)."Vinca Alkaloids".International Journal of Preventive Medicine.4(11): 1231–1235.PMC3883245.PMID24404355.

- ^Fabricant, D. S., Farnsworth, N. R. (March 2001)."The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery".Environ. Health Perspect.109(Suppl 1): 69–75.doi:10.1289/ehp.01109s169.PMC1240543.PMID11250806.

- ^Baell J, Walters MA (24 September 2014)."Chemistry: Chemical con artists foil drug discovery".Nature.513(7519): 481–483.Bibcode:2014Natur.513..481B.doi:10.1038/513481a.PMID25254460.

- ^Dahlin JL, Walters MA (July 2014)."The essential roles of chemistry in high-throughput screening triage".Future Medicinal Chemistry.6(11): 1265–90.doi:10.4155/fmc.14.60.PMC4465542.PMID25163000.

- ^Newman DJ, Cragg GM (8 February 2012)."Natural Products As Sources of New Drugs over the 30 Years from 1981 to 2010".Journal of Natural Products.75(3): 311–35.doi:10.1021/np200906s.PMC3721181.PMID22316239.

- ^ab"State of the World's Plants and Fungi 2020"(PDF).Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.2020.Archived(PDF)from the original on 5 October 2020.Retrieved30 September2020.

- ^Freye E (2010). "Toxicity of Datura Stramonium".Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs.Springer. pp. 217–218.doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2448-0_34.ISBN978-90-481-2447-3.

- ^Ernst E (1998)."Harmless Herbs? A Review of the Recent Literature"(PDF).The American Journal of Medicine.104(2): 170–178.doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00397-5.PMID9528737.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2019-11-05.Retrieved2013-11-28.

- ^Talalay P (2001)."The importance of using scientific principles in the development of medicinal agents from plants".Academic Medicine.76(3): 238–47.doi:10.1097/00001888-200103000-00010.PMID11242573.

- ^Elvin-Lewis M (2001). "Should we be concerned about herbal remedies".Journal of Ethnopharmacology.75(2–3): 141–164.doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00394-9.PMID11297844.

- ^Vickers, A. J. (2007)."Which botanicals or other unconventional anticancer agents should we take to clinical trial?".J Soc Integr Oncol.5(3): 125–9.PMC2590766.PMID17761132.

- ^Ernst, E. (2007). "Herbal medicines: balancing benefits and risks".Dietary Supplements and Health.Novartis Foundation Symposia. Vol. 282. Novartis Foundation Symposium. pp. 154–67, discussion 167–72, 212–8.doi:10.1002/9780470319444.ch11.ISBN978-0-470-31944-4.PMID17913230.

- ^Pinn G (November 2001). "Adverse effects associated with herbal medicine".Aust Fam Physician.30(11): 1070–5.PMID11759460.

- ^Nekvindová J, Anzenbacher P (July 2007). "Interactions of food and dietary supplements with drug metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes".Ceska Slov Farm.56(4): 165–73.PMID17969314.

- ^Born D, Barron ML (May 2005). "Herb use in pregnancy: what nurses should know".MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs.30(3): 201–6.doi:10.1097/00005721-200505000-00009.PMID15867682.S2CID35882289.

- ^Barrett, Stephen (23 November 2013)."The herbal minefield".Quackwatch. Archived fromthe originalon 18 August 2018.Retrieved17 November2017.

- ^Zhang J, Wider B, Shang H, Li X, Ernst E (2012). "Quality of herbal medicines: Challenges and solutions".Complementary Therapies in Medicine.20(1–2): 100–106.doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2011.09.004.PMID22305255.

- ^Morris CA, Avorn J (2003). "Internet marketing of herbal products".JAMA.290(11): 1505–9.doi:10.1001/jama.290.11.1505.PMID13129992.

- ^Coghlan ML, Haile J, Houston J, Murray DC, White NE, Moolhuijzen P, Bellgard MI, Bunce M (2012)."Deep Sequencing of Plant and Animal DNA Contained within Traditional Chinese Medicines Reveals Legality Issues and Health Safety Concerns".PLOS Genetics.8(4): e1002657.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002657.PMC3325194.PMID22511890.

- ^Lordan R (2021)."Dietary supplements and nutraceuticals market growth during the coronavirus pandemic - implications for consumers and regulatory oversight".Pharmanutrition.18.Elsevier Public Health Emergency Collection: 100282.doi:10.1016/j.phanu.2021.100282.PMC8416287.PMID34513589.

- ^"United States Files Enforcement Action to Stop Deceptive Marketing of Herbal Tea Product Advertised as Covid-19 Treatment".United States Department of Justice.Department of Justice. 3 March 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 3 October 2022.Retrieved3 October2022.

- ^abKling J (2016). "Protecting medicine's wild pharmacy".Nature Plants.2(5): 16064.doi:10.1038/nplants.2016.64.PMID27243657.S2CID7246069.

- ^Briggs H (30 September 2020)."Two-fifths of plants at risk of extinction, says report".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2020.Retrieved30 September2020.

![The opium poppy Papaver somniferum is the source of the alkaloids morphine and codeine.[63]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Opium_poppy.jpg/160px-Opium_poppy.jpg)

![The alkaloid nicotine from tobacco binds directly to the body's Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, accounting for its pharmacological effects.[69]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Nicotine.svg/143px-Nicotine.svg.png)

![Deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna, yields tropane alkaloids including atropine, scopolamine and hyoscyamine.[65]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Atropa_belladonna_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-018.jpg/104px-Atropa_belladonna_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-018.jpg)

![Senna alexandrina, containing anthraquinone glycosides, has been used as a laxative for millennia.[72]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Senna_alexandrina_Mill.-Cassia_angustifolia_L._%28Senna_Plant%29.jpg/161px-Senna_alexandrina_Mill.-Cassia_angustifolia_L._%28Senna_Plant%29.jpg)

![The foxglove, Digitalis purpurea, contains digoxin, a cardiac glycoside. The plant was used on heart conditions long before the glycoside was identified.[55][74]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Digitalis_purpurea2.jpg/90px-Digitalis_purpurea2.jpg)

![Digoxin is used to treat atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter and sometimes heart failure.[55]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Digoxin.svg/200px-Digoxin.svg.png)

![Polyphenols include phytoestrogens (top and middle), mimics of animal estrogen (bottom).[83]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Phytoestrogens2.png/160px-Phytoestrogens2.png)

![The essential oil of common thyme (Thymus vulgaris), contains the monoterpene thymol, an antiseptic and antifungal.[87]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Thymian.jpg/181px-Thymian.jpg)

![Thymol is one of many terpenes found in plants.[87]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Thymol2.svg/97px-Thymol2.svg.png)