Memento mori

Memento mori(Latin for "remember (that you have) to die" )[2]is an artistic or symbolictropeacting as a reminder of the inevitability ofdeath.[2]The concept has its roots in the philosophers ofclassical antiquityandChristianity,and appeared infunerary artand architecture from the medieval period onwards.

The most commonmotifis a skull, often accompanied by bones. Often this alone is enough to evoke the trope, but other motifs include a coffin,hourglass,or wilting flowers to signify the impermanence of life. Often these function within a work whose main subject is something else, such as a portrait, but thevanitasis an artistic genre where the theme of death is the main subject. TheDanse Macabreand death personified with a scythe as theGrim Reaperare even more direct evocations of the trope.

Pronunciation and translation

[edit]In English, the phrase is typically pronounced/məˈmɛntoʊˈmɔːri/,mə-MEN-tohMOR-ee.

Mementois the2nd person singularactivefutureimperativeofmeminī,'to remember, to bear in mind', usually serving as a warning: "remember!"Morīis thepresentinfinitiveof thedeponent verbmorior'to die'.[3]Thus, the phrase literally translates as "you must remember to die" but may be loosely rendered as "remember death" or "remember that you die".[4]

History of the concept

[edit]In classical antiquity

[edit]The philosopherDemocritustrained himself by going into solitude and frequenting tombs.[5]Plato'sPhaedo,where the death ofSocratesis recounted, introduces the idea that the proper practice of philosophy is "about nothing else but dying and being dead".[6]

TheStoicsofclassical antiquitywere particularly prominent in their use of this discipline, andSeneca's letters are full of injunctions to meditate on death.[7]The StoicEpictetustold his students that when kissing their child, brother, or friend, they should remind themselves that they are mortal, curbing their pleasure, as do "those who stand behind men in their triumphs and remind them that they are mortal".[8]The StoicMarcus Aureliusinvited the reader (himself) to "consider how ephemeral and mean all mortal things are" in hisMeditations.[9][10]

In some accounts of theRoman triumph,a companion orpublic slavewould stand behind or near thetriumphant generalduring the procession and remind him from time to time of his own mortality or prompt him to "look behind".[11]A version of this warning is often rendered into English as "Remember, Caesar, thou art mortal", for example inFahrenheit 451.

In early Christianity

[edit]Several passages in the Old Testament urge a remembrance of death. InPsalm 90,Moses prays that God would teach his people "to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom" (Ps. 90:12). InEcclesiastes,the Preacher insists that "It is better to go to the house of mourning than to go to the house of feasting, for this is the end of all mankind, and the living will lay it to heart" (Eccl. 7:2). In Isaiah, the lifespan of human beings is compared to the short lifespan of grass: "The grass withers, the flower fades when the breath of the LORD blows on it; surelythe people are grass"(Is. 40:7).

The expressionmemento morideveloped with the growth of Christianity, which emphasizedHeaven,Hell,Hadesand salvation of the soul in theafterlife.[12] The 2nd-century Christian writerTertullianclaimed in hisApologeticus,that during atriumphal procession,a victorious general had someone standing behind him, holding a crown over his head and whispering: "Respice post te. Hominem te esse memento. Memento mori."(" Look after yourself. Remember you're a man. Remember you will die. "). Though in modern times this has become a standardtrope,in fact no other ancient authors confirm this, and it may have been Christian moralizing on Tertullians part rather than an accurate historical report.[13]

In Europe from the medieval era to the Victorian era

[edit]Christian Theology

[edit]The thought was then utilized in Christianity, whose strong emphasis ondivine judgment,heaven,hell,and thesalvation of the soulbrought death to the forefront of consciousness.[14]In the Christian context, thememento moriacquires a moralizing purpose quite opposed to thenunc est bibendum(now is the time to drink) theme ofclassical antiquity.To the Christian, the prospect of death serves to emphasize the emptiness and fleetingness of earthly pleasures, luxuries, and achievements, and thus also as an invitation to focus one's thoughts on the prospect of the afterlife. A Biblical injunction often associated with thememento moriin this context isIn omnibus operibus tuis memorare novissima tua, et in aeternum non peccabis(theVulgate's Latin rendering ofEcclesiasticus7:40,"in all thy works be mindful of thy last end and thou wilt never sin." ) This finds ritual expression in the rites ofAsh Wednesday,when ashes are placed upon the worshipers' heads with the words, "Remember Man that you are dust and unto dust, you shall return."

Memento morihas been an important part ofasceticdisciplines as a means of perfecting the character by cultivating detachment and other virtues, and by turning the attention towards theimmortalityof the soul and the afterlife.[15]

Architecture

[edit]

The most obvious places to look formemento morimeditations are in funeral art andarchitecture.Perhaps the most striking to contemporary minds is thetransiorcadaver tomb,a tomb that depicts the decayedcorpseof the deceased. This became a fashion in the tombs of the wealthy in the fifteenth century, and surviving examples still offer a stark reminder of the vanity of earthly riches. Later,Puritantomb stonesin the colonial United States frequently depicted winged skulls, skeletons, orangelssnuffing out candles. These are among the numerousthemes associated with skull imagery.

Another example ofmemento moriis provided by the chapels of bones, such as theCapela dos OssosinÉvoraor theCapuchin Cryptin Rome. These are chapels where the walls are totally or partially covered by human remains, mostly bones. The entrance to the Capela dos Ossos has the following sentence: "We bones, lying here bare, await yours."

Visual art

[edit]

Timepieces have been used to illustrate that the time of the living on Earth grows shorter with each passing minute. Publicclockswould be decorated with mottos such asultima forsan( "perhaps the last" [hour]) orvulnerant omnes, ultima necat( "they all wound, and the last kills" ). Clocks have carried the mottotempus fugit,"time flees". Old striking clocks often sportedautomatawho would appear and strike the hour; some of the celebrated automaton clocks fromAugsburg,Germany, had Death striking the hour. Private people carried smaller reminders of their own mortality.Mary, Queen of Scotsowned a large watch carved in the form of asilverskull, embellished with the lines ofHorace,"Pale death knocks with the same tempo upon the huts of the poor and the towers of Kings."

In the late 16th and through the 17th century,memento morijewelry was popular. Items includedmourning rings,[16]pendants,lockets,andbrooches.[17]These pieces depicted tiny motifs of skulls, bones, and coffins, in addition to messages and names of the departed, picked out inprecious metalsandenamel.[17][18]

During the same period there emerged the artistic genre known asvanitas,Latin for "emptiness" or "vanity". Especially popular inHollandand then spreading to otherEuropean nations,vanitas paintings typically represented assemblages of numerous symbolic objects such as human skulls, guttering candles, wilting flowers, soap bubbles, butterflies, and hourglasses. In combination, vanitas assemblies conveyed the impermanence of human endeavours and of the decay that is inevitable with the passage of time. See also the themes associated withthe image of the skull.The 2007screenprintby the street-artistBanksy"Grin Reaper" features theGrim Reaperwith acid-house smiley face sitting on a clock demonstrating death awaiting us all.[19]

Literature

[edit]Memento moriis also an important literary theme. Well-known literary meditations on death in English prose include SirThomas Browne'sHydriotaphia, Urn BurialandJeremy Taylor'sHoly Living and Holy Dying.These works were part of aJacobeancult of melancholiathat marked the end of theElizabethan era.In the late eighteenth century, literaryelegieswere a common genre;Thomas Gray'sElegy Written in a Country ChurchyardandEdward Young'sNight Thoughtsare typical members of the genre.

In the European devotional literature of the Renaissance, theArs Moriendi,memento morihad moral value by reminding individuals of their mortality.[20]

Music

[edit]Apart from the genre ofrequiemand funeral music, there is also a rich tradition ofmemento moriin theEarly Musicof Europe. Especially those facing the ever-present death during the recurringbubonic plaguepandemicsfrom the 1340s onward tried to toughen themselves by anticipating the inevitable inchants,from the simpleGeisslerliederof theFlagellantmovement to the more refined cloistral or courtly songs. The lyrics often looked at life as a necessary and god-givenvale of tearswith death as a ransom, and they reminded people to lead sinless lives to stand a chance atJudgment Day.The following two Latin stanzas (with their English translations) are typical ofmemento moriin medieval music; they are from thevirelaiAd Mortem Festinamusof theLlibre Vermell de Montserratfrom 1399:

Vita brevis breviter in brevi finietur, |

Life is short, and shortly it will end; |

Danse macabre

[edit]Thedanse macabreis another well-known example of thememento moritheme, with its dancing depiction of theGrim Reapercarrying off rich and poor alike. This and similar depictions of Death decorated many European churches.

Gallery

[edit]-

Romanmosaicrepresenting theWheel of Fortunewhich, as it turns, can make the rich poor and the poor rich; in effect, both states are very precarious, with death never far and life hanging by a thread: when it breaks, the soul flies off. And thus are all made equal. (Collezionipompeiane.Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli)

-

Prince of OrangeRené of Châlondied in 1544 at age 25. His widow commissioned sculptor Ligier Richier to represent him in theCadaver Tomb of René of Chalon,which shows him offering his heart to God, set against the painted splendour of his former worldly estate. (Church of Saint-Étienne,Bar-le-Duc)

-

French 16th/17th-centuryivorypendant,Monkand Death, recalling mortality and the certainty of death (Walters Art Museum)

-

Memento mori ring, with enameled skull and "Die to Live" message (between 1500 and 1650,British Museum,London)

-

Memento mori in the form of a small coffin, 1700s, wax figure on silk in a wooden coffin (Museum Schnütgen, Cologne, Germany)

-

Mourning brooch with plaited hair, 1843 (Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira,New Zealand)

-

Alarm clock, mounted on model of coffin, probably English, 1840–1900 (Science Museum, London)

-

Still Life: An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Lifeis a Dutchvanitaswhich follows the memento mori theme.

-

Hans Holbein'sThe Ambassadorsincludes a distorted image of a skull across the bottom of the painting.

The salutation of the Hermits of St. Paul of France

[edit]Memento moriwas the salutation used by theHermits of St. Paul of France(1620–1633), also known as the Brothers of Death.[21]It is sometimes claimed that theTrappistsuse this salutation, but this is not true.[22]

In Puritan America

[edit]

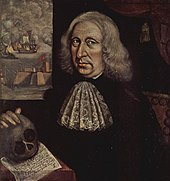

Colonial American artsaw a large number ofmemento moriimages due toPuritaninfluence. The Puritan community in 17th-century North America looked down upon art because they believed that it drew the faithful away from God and, if away from God, then it could only lead to the devil. However, portraits were considered historical records and, as such, they were allowed.Thomas Smith,a 17th-century Puritan, fought in many naval battles and also painted. In his self-portrait, we see these pursuits represented alongside a typical Puritanmemento moriwith a skull, suggesting his awareness of imminent death.

The poem underneath the skull emphasizes Thomas Smith's acceptance of death and of turning away from the world of the living:

Why why should I the World be minding, Therein a World of Evils Finding. Then Farwell World: Farwell thy jarres, thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs. Truth Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternall Drawes to him my heart, By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne me (after Grace) with Glory.

Mexico's Day of the Dead

[edit]

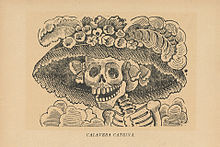

Muchmemento moriart is associated with theMexican festivalDay of the Dead,including skull-shaped candies and bread loaves adorned with bread "bones".

This theme was also famously expressed in the works of the Mexican engraverJosé Guadalupe Posada,in which people from various walks of life are depicted as skeletons.

Another manifestation ofmemento moriis found in the Mexican "Calavera", a literary composition in verse form normally written in honour of a person who is still alive, but written as if that person were dead. These compositions have a comedic tone and are often offered from one friend to another duringDay of the Dead.[23]

Contemporary culture

[edit]Roman Krznaricsuggests Memento Mori is an important topic to bring back into our thoughts and belief system; "Philosophers have come up with lots of what I call 'death tasters' – thought experiments for seizing the day."

These thought experiments are powerful to get us re-oriented back to death into current awareness and living with spontaneity.Albert Camusstated "Come to terms with death, thereafter anything is possible."Jean-Paul Sartreexpressed that life is given to us early, and is shortened at the end, all the while taken away at every step of the way, emphasizing that the end is only the beginning every day.[24]

Similar concepts across cultures

[edit]In Buddhism

[edit]The Buddhist practicemaraṇasatimeditates on death. The word is aPālicompound ofmaraṇa'death' (anIndo-Europeancognate of Latinmori) andsati'awareness', so very close tomemento mori.It is first used in early Buddhist texts, thesuttapiṭakaof thePāli Canon,with parallels in theāgamasof the "Northern" Schools.

In Japanese Zen and samurai culture

[edit]In Japan, the influence ofZenBuddhist contemplation of death on indigenous culture can be gauged by the following quotation from the classic treatise onsamuraiethics,Hagakure:[25]

The Way of the Samurai is, morning after morning, the practice of death, considering whether it will be here or be there, imagining the most sightly way of dying, and putting one's mind firmly in death. Although this may be a most difficult thing, if one will do it, it can be done. There is nothing that one should suppose cannot be done.[26]

In the annual appreciation ofcherry blossomand fall colors,hanamiandmomijigari,it was philosophized that things are most splendid at the moment before their fall, and to aim to live and die in a similar fashion.[citation needed]

In Tibetan Buddhism

[edit]

In Tibetan Buddhism, there is a mind training practice known asLojong.The initial stages of the classic Lojong begin with 'The Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind', or, more literally, 'Four Contemplations to Cause a Revolution in the Mind'.[citation needed]The second of these four is the contemplation on impermanence and death. In particular, one contemplates that;

- All compounded things are impermanent.

- The human body is a compounded thing.

- Therefore, death of the body is certain.

- The time of death is uncertain and beyond our control.

There are a number of classic verse formulations of these contemplations meant for daily reflection to overcome our strong habitual tendency to live as though we will certainly not die today.

Lalitavistara Sutra

[edit]The following is from theLalitavistara Sūtra,a major work in the classical Sanskrit canon:

ज्वलितं त्रिभवं जरव्याधिदुखैः मरणाग्निप्रदीप्तमनाथमिदम्। |

Beings are ablaze with the sufferings of sickness and old age, |

The Udānavarga

[edit]A very well known verse in the Pali, Sanskrit and Tibetan canons states [this is from the Sanskrit version, theUdānavarga:

सर्वे क्षयान्ता निचयाः पतनान्ताः समुच्छ्रयाः | |

All that is acquired will be lost |

Shantideva, Bodhicaryavatara

[edit]Shantideva,in theBodhisattvacaryāvatāra'Bodhisattva's Way of Life' reflects at length:

कृताकृतापरीक्षोऽयं मृत्युर्विश्रम्भघातकः। |

Death does not differentiate between tasks done and undone. |

In more modern Tibetan Buddhist works

[edit]In a practice text written by the 19th century Tibetan masterDudjom Lingpafor seriousmeditators,he formulates the second contemplation in this way:[29][30]

On this occasion when you have such a bounty of opportunities in terms of your body, environment, friends, spiritual mentors, time, and practical instructions, without procrastinating until tomorrow and the next day, arouse a sense of urgency, as if a spark landed on your body or a grain of sand fell in your eye. If you have not swiftly applied yourself to practice, examine the births and deaths of other beings and reflect again and again on the unpredictability of your lifespan and the time of your death, and on the uncertainty of your own situation. Meditate on this until you have definitively integrated it with your mind... The appearances of this life, including your surroundings and friends, are like last night's dream, and this life passes more swiftly than a flash of lightning in the sky. There is no end to this meaningless work. What a joke to prepare to live forever! Wherever you are born in the heights or depths of saṃsāra, the great noose of suffering will hold you tight. Acquiring freedom for yourself is as rare as a star in the daytime, so how is it possible to practice and achieve liberation? The root of all mind training and practical instructions is planted by knowing the nature of existence. There is no other way. I, an old vagabond, have shaken my beggar's satchel, and this is what came out.

The contemporary Tibetan master,Yangthang Rinpoche,in his short text 'Summary of the View, Meditation, and Conduct':[31]

།ཁྱེད་རྙེད་དཀའ་བ་མི་ཡི་ལུས་རྟེན་རྙེད། །སྐྱེ་དཀའ་བའི་ངེས་འབྱུང་གི་བསམ་པ་སྐྱེས། །མཇལ་དཀའ་བའི་མཚན་ལྡན་གྱི་བླ་མ་མཇལ། །འཕྲད་དཀའ་བ་དམ་པའི་ཆོས་དང་འཕྲད། |

You have obtained a human life, which is difficult to find, |

The Tibetan Canon also includes copious materials on the meditative preparation for the death process and intermediate periodbardobetween death and rebirth. Amongst them are the famous "Tibetan Book of the Dead", in TibetanBardo Thodol,the "Natural Liberation through Hearing in the Bardo".

In Islam

[edit]The "remembrance of death" (Arabic:تذكرة الموت,Tadhkirat al-Mawt;deriving fromتذكرة,tadhkirah,Arabic formemorandumoradmonition), has been a major topic of Islamic spirituality since the time of the Islamic prophetMuhammadinMedina.It is grounded in theQur'an,where there are recurring injunctions to pay heed to the fate of previous generations.[32]Thehadithliterature, which preserves the teachings of Muhammad, records advice for believers to "remember often death, the destroyer of pleasures."[33]SomeSufishave been called "ahl al-qubur," the "people of the graves," because of their practice of frequenting graveyards to ponder on mortality and the vanity of life, based on the teaching of Muhammad to visit graves.[34]Al-Ghazalidevotes to this topic the last book of his "The Revival of the Religious Sciences".[35]

Iceland

[edit]TheHávamál( "Sayings of the High One" ), a 13th-century Icelandic compilation poetically attributed to the godOdin,includes two sections – the Gestaþáttr and the Loddfáfnismál – offering manygnomicproverbs expressing the memento mori philosophy, most famously Gestaþáttr number 77:

Deyr fé, |

Animals die, |

See also

[edit]- Gerascophobia(fear ofaging)

- Gerontophobia(fear ofelderly people)

- Carpe diem

- Et in Arcadia ego

- La Calavera Catrina

- Mono no aware

- Mortality salience

- Sic transit gloria mundi

- Tempus fugit

- Terror management theory

- Ubi sunt

- Vanitas

- YOLO (aphorism)

References

[edit]- ^Campbell, Lorne.Van der Weyden.London: Chaucer Press, 2004. 89.ISBN1904449247

- ^abLiterally 'remember (that you have) to die',Oxford English Dictionary,Third Edition, June 2001.

- ^Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short,A Latin Dictionary,ss.vv.

- ^Oxford English Dictionary,Third Edition,s.v.

- ^Diogenes LaertiusLives of the Eminent Philosophers,Book IX, Chapter 7, Section 38Archived5 January 2017 at theWayback Machine

- ^Phaedo,64a4.

- ^See hisMoral Letters to Lucilius.

- ^Discourses of Epictetus,3.24.

- ^Henry Albert Fischel,Rabbinic Literature and Greco-Roman Philosophy: A Study of Epicurea and Rhetorica in Early Midrashic Writings,E. J. Brill, 1973, p. 95.

- ^Marcus Aurelius,MeditationsIV. 48.2.

- ^Beard, Mary: The Roman Triumph, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., and London, England, 2007. (hardcover), pp. 85–92.

- ^"Final Farewell: The Culture of Death and the Afterlife".Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri. Archived fromthe originalon 6 June 2010.Retrieved13 January2015.

- ^Mary Beard,The Roman Triumph,Harvard University Press,2009,ISBN0674032187,pp. 85–92

- ^Christian Dogmatics, Volume 2 (Carl E. Braaten, Robert W. Jenson), page 583

- ^See Jeremy Taylor,Holy Living and Holy Dying.

- ^Taylor, Gerald; Scarisbrick, Diana (1978).Finger Rings From Ancient Egypt to the Present Day.Ashmolean Museum.p. 76.ISBN0900090545.

- ^ab"Memento Mori".Antique Jewelry University.Lang Antiques. n.d.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2020.Retrieved11 August2020.

- ^Bond, Charlotte (5 December 2018)."Somber" Memento Mori "Jewelry Commissioned to Help People Mourn".The Vintage News.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2020.Retrieved11 August2020.

- ^"Banksy Grin Reaper | Meaning & History".Andipa Editions.Archivedfrom the original on 1 September 2023.Retrieved1 September2023.

- ^Michael John Brennan, ed.,The A–Z of Death and Dying: Social, Medical, and Cultural Aspects,ISBN1440803447,s.v."Memento Mori", p. 307fands.v."Ars Moriendi", p. 44

- ^F. McGahan, "Paulists",The Catholic Encyclopedia,1912,s.v.Paulists

- ^E. Obrecht, "Trappists",The Catholic Encyclopedia,1912,s.v.Trappists

- ^Stanley Brandes. "Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond". Chapter 5: The Poetics of Death. John Wiley & Sons, 2009

- ^Macdonald, Fiona."What it really means to 'Seize the day'".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 17 June 2019.Retrieved16 June2019.

- ^"Hagakure: Book of the Samurai".www.themathesontrust.org.Archivedfrom the original on 28 February 2022.Retrieved28 February2022.

- ^"A Buddhist Guide to Death, Dying and Suffering".www.urbandharma.org.Archivedfrom the original on 4 August 2018.Retrieved28 February2022.

- ^"84000 Reading Room | The Play in Full".84000 Translating The Words of The Buddha.Archivedfrom the original on 1 March 2022.Retrieved10 May2020.

- ^Udānavarga, 1:22.

- ^"Foolish Dharma of an Idiot Clothed in Mud and Feathers, in 'Dujdom Lingpa's Visions of the Great Perfection, Volume 1', B. Alan Wallace (translator), Wisdom Publications".

An oral commentary by the translator is available on YouTubeArchived23 November 2022 at theWayback Machine - ^"Natural Liberation | Wisdom Publications".Archived fromthe originalon 31 March 2019.Retrieved2 June2022.

- ^The English text is availablehere.Archived2018-05-14 at theWayback MachineThe Tibetan text is availablehere.Archived30 August 2018 at theWayback MachineOral Commentary by a student of Rinpoche, B. Alan Wallace, is availablehere.Archived2 September 2018 at theWayback Machine

- ^For instance, sura "Yasin", 36:31, "Have they not seen how many generations We destroyed before them, which indeed returned not unto them?".

- ^"Riyad as-Salihin 579 – The Book of Miscellany – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)".sunnah.com.Archivedfrom the original on 28 February 2022.Retrieved28 February2022.

- ^"Sunan Abi Dawud 3235 – Funerals (Kitab Al-Jana'iz) – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)".sunnah.com.Archivedfrom the original on 28 February 2022.Retrieved28 February2022.

- ^Al-Ghazali on Death and the Afterlife, tr. byT.J. Winter.Cambridge,Islamic Texts Society,1989.

External links

[edit] Media related toMemento moriat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toMemento moriat Wikimedia Commons