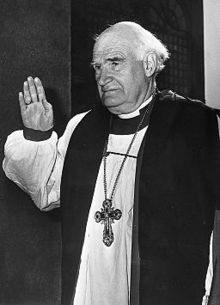

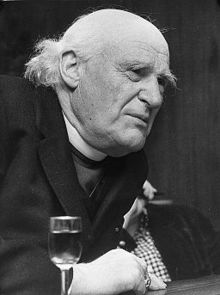

Michael Ramsey

Michael Ramsey | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

| |

| Church | Church of England |

| Diocese | Canterbury |

| Appointed | 31 May 1961 |

| In office | 1961–1974 |

| Predecessor | Geoffrey Fisher |

| Successor | Donald Coggan |

| Other post(s) | Primate of All England |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 23 September 1928(deacon) 22 September 1929(priest) byAlbert David |

| Consecration | 29 September 1952(bishop) byCyril Garbett |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Arthur Michael Ramsey 14 November 1904 |

| Died | 23 April 1988(aged 83) Oxford,Oxfordshire,England |

| Buried | Canterbury Cathedral |

| Nationality | British |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Parents | Arthur Stanley Ramsey& Agnes Wilson |

| Spouse | Joan Hamilton |

| Previous post(s) | Bishop of Durham(1952–1956) Archbishop of York(1956–1961) |

| Signature | |

Arthur Michael Ramsey, Baron Ramsey of Canterbury,PC(14 November 1904 – 23 April 1988) was a BritishChurch of Englandbishop andlife peer.He served as the 100thArchbishop of Canterbury.He was appointed on 31 May 1961 and held the office until 1974, having previously been appointedBishop of Durhamin 1952 and theArchbishop of Yorkin 1956.

He was known as a theologian, educator, and advocate of Christian unity.[1]

Early life[edit]

Ramsey was born inCambridge,England in 1904. His parents wereArthur Stanley Ramsey(1867–1954) and Mary Agnes Ramsey née Wilson (1875–1927); his father was aCongregationalistand mathematician and his mother was a socialist andsuffragette.[2]He was educated atSandroyd School,Wiltshire,King's College School, Cambridge,[3]Repton School(where the headmaster was a futureArchbishop of Canterbury,Geoffrey Francis Fisher) andMagdalene College, Cambridge,where his father was president of the college. At university he was president of theCambridge Union Societyand his support for theLiberal Partywon him praise fromH. H. Asquith.[4]

Ramsey's elder brother,Frank P. Ramsey(1903–1930), was amathematicianandphilosopher(of atheist convictions).[5]He was something of a prodigy who, when only 19, translatedWittgenstein'sTractatusinto English.[6]

During his time in Cambridge, Ramsey came under the influence of theAnglo-Catholicdean ofCorpus Christi College,Edwyn Clement Hoskyns.On the advice ofEric Milner-Whitehe trained atCuddesdon,where he became friends withAustin Farrerand was introduced toOrthodox Christianideas byDerwas Chitty.[7]He graduated in 1927 with a First-class degree in Theology.[8]

Ordained ministry[edit]

Ramsey was ordained in 1928 and became a curate inLiverpool,where he was influenced byCharles Raven.[2]

After this he became a lecturer to ordination candidates at theBishop's HostelinLincoln.During this time he published a book,The Gospel and the Catholic Church(1936). He then ministered atSt Botolph's Church, Bostonand atSt Bene't's Church,Cambridge, before being offered a canonry atDurham Cathedraland theVan Mildert Chair of Divinityin the Department of Theology atDurham University.After this, in 1950, he became theRegius Professor of Divinityat Cambridge, but left to become a bishop after only a short time in office.[9]

Ramsey married Joan A. C. Hamilton (1910–1995) at Durham in the early summer of 1942.[10][11]

Episcopal ministry[edit]

In 1952, he was appointedBishop of Durham.He was consecrated a bishop byCyril Garbett,Archbishop of York,atYork MinsteronMichaelmas(29 September) that year[12](by which hiselectionto the See of Durham must have already beenconfirmed). In 1956 he becameArchbishop of Yorkand, in 1961,Archbishop of Canterbury.[8]During his time as archbishop he travelled widely and saw the creation of theGeneral Synod.Retirement ages for clergy were cut from 75 to 70.[13]

Theology and churchmanship[edit]

Ramsey’s “life was rooted in prayer, worship and a sense of the reality of God, yet this was all tempered with a sense of humour which prevented it from ever degenerating into pomposity or unreal pietism. This spiritual depth was just as important for his leadership in an unsettled time as was his intellectual and theological power.”[14]

In a lecture on Ramsey,John Macquarrieasked, “what kind of theologian was he?” and answered that “he was thoroughly Anglican.” Macquarrie explained that Ramsey's theology is (1) “based on the scriptures”, (2) the church's “tradition”, and (3) “reason and conscience”. Ramsey held to theAnglo-Catholictradition, but he appreciated other points of view. This was especially true after he became a bishop who ministered to diverse Anglicans.[14]

As an Anglo-Catholic with anonconformistbackground, Ramsey had a broad religious outlook. He had a particular regard for theEastern Orthodoxconcept of "glory", and his favourite book he had written was his 1949 workThe Transfiguration.[2]

Ramsey's first reaction toJ. A. T. Robinson'sHonest to God(1963) was hostile.[14]However, he soon published a short response entitledImage Old and New,in which he engaged seriously with Robinson's ideas.[2]

Conscious always of the atheism which his short-lived brother Frank had espoused, he maintained a lifelong respect for honest unbelief, and considered that such unbelief would not automatically be a barrier to salvation.[2]Acting on his respect for beliefs other than his, Ramsey made a barefoot visit to the grave of Mahatma Gandhi.[15]

Although he disagreed with a lot ofKarl Barth's thinking, his relations with him were warm.[2]

Following observations of a religious mission at Cambridge, he had an early dislike of evangelists and mass rallies, which he feared relied too much on emotion. This led him to be critical ofBilly Graham,although the two later became friends and Ramsey even took to the stage at a Graham rally inRio de Janeiro.[2]One of his later books,The Charismatic Christ(1973), engaged with thecharismatic movement.

Ramsey believed there was no decisive theological argument against women priests, although he was not entirely comfortable with this development. The first women priests in theAnglican Communionwere ordained during his time as Archbishop of Canterbury.[2]In retirement he received communion from a woman priest in the United States.[15]

Ecumenical activities[edit]

Ramsey was active in theecumenicalmovement, and while Archbishop of Canterbury in 1966 he metPope Paul VIin Rome, where the Pope presented him with the episcopal (bishop's) ring he had worn asArchbishop of Milan.[16]The two prelates issued "The Common Declaration by Pope Paul VI and the Archbishop of Canterbury Dr Michael Ramsey". In it they said that their meeting "marks a new stage in the development of fraternal relations, based upon Christian charity, and of sincere efforts to remove the causes of conflict and to re-establish unity."[17]

Ramsey preached at the Roman CatholicSt Patrick's Cathedralin New York City in 1972. It was the first time that a leader of the Anglican Communion had done so.[18]However, while fostering ties with the Roman Catholic Church, Ramsey criticised the Pope's 1968 encyclicalHumanae Vitaeagainst birth control.[18]

These warm relations with Rome caused Ramsey to be dogged by protests by fundamentalist Protestants, particularlyIan Paisley.[15]

Ramsey encouraged efforts to promote closerrelations between Anglicans and Orthodox.[14]He enjoyed friendship with the OrthodoxPatriarch of Constantinople,Athenagoras,andAlexius,Patriarch of Moscow.[2]

As Archbishop of Canterbury, Ramsey served as president of theWorld Council of Churches(1961–68).[1]However, he opposed the granting of aid money by the World Council of Churches to guerrilla groups.[2]

Ramsey's willingness to talk to officially sanctioned churches in theEastern Blocled to criticisms fromRichard Wurmbrand.[15]

He also supportedefforts to unitethe Church of England with theMethodist Churchand was disappointed when the plans fell through.[2]

Politics[edit]

Before entering the clergy, Michael Ramsey had participated in the Liberal Party. In 1925, Ramsey travelled with the debate club and spoke at multiple venues in the United States. Upon his return, he heardLord Hugh Cecilremark that the Church was the place to go for those who wanted to help people, and Ramsey heard that as his vocation from God. He had sympathies with liberal politics for the rest of his life and admiredH. H. Asquith.[19][20]He became close friends with party leaderJeremy Thorpe.Ramsey and his wife Joan were godparents of Thorpe's son Rupert, whom Ramsey baptized in 1969, and Ramsey officiated at Thorpe's second marriage toMarion Stein.Both Ramsey and Thorpe had lost family members to car collisions: Ramsey's mother in 1927 and Thorpe's first wife Caroline in 1970.

Ramsey disliked the power of the government over the church. "Establishment has never been one of my enthusiasms," he said, and "he was not at ease with the royal family."[2]He supported thedecriminalisation of homosexualityin the 1960s, which brought him enemies in theHouse of Lords.[2][18]

In 1965, "he outraged right-wingers when he declared that under certain circumstances, there would be Christian justice in using British troops to overthrow the white-minority regime [ofIan Smith] inRhodesia."[18]This was responded to by a government member saying: "This is a fine time to sing 'Onward Christian soldiers,shoot your kith and kin.' "[21]He also called theVietnam Wara "futility".[18]Regarding Africa, Ramsey opposed curbs on immigration to the UK ofKenyan Asians,which he saw as a betrayal by Britain of a promise. He was againstapartheid,and he left an account of a very frosty encounter withJohn Vorster.[2]In 1970, Ramsey attacked apartheid, saying that it was "being increased by more ruthless actions” and describing it as an "abuse of power at the expense of others".[18]He was also a critic of the Chilean dictatorAugusto Pinochet.[2]

Later life[edit]

After retiring as Archbishop of Canterbury on 15 November 1974[22]he was created alife peer,asBaron Ramsey of Canterbury,ofCanterburyin Kent, enabling him to remain in theHouse of Lordswhere he had previously sat as one of theLords Spiritual.

Although retired, Ramsey remained active, "a fact reflected in his writing of four books and numerous additional undertakings".[23]

He went to live first at Cuddesdon, where he did not settle particularly well, and then for a number of years back in Durham, where he was regularly seen slowly making his way through thecathedral,and talking to students. A benevolent and popular figure, he occasionally participated in services there, notably giving an address at the 1984 dedication of theMarks & Spencerfinanced Daily Bread window, on the topic of St Michael.[24]However, Durham's hills were rather steep for him and he and Lady Ramsey accepted the offer of a flat atBishopthorpein York by then archbishopJohn Habgood.They stayed there just over a year, moving finally to St John's Home, attached to theAll Saints' SistersinCowley, Oxford,where he died in April 1988.[2]

During his retirement, he also spent several terms atNashotah House,an Anglo-Catholic seminary of the Episcopal Church in Wisconsin where he was much beloved by students. A first-floor flat was designated "Lambeth West" for his personal use. A stained-glass window in the Chapel, bears his image and the same inscription as is on the memorial near his grave.[2]The window (placed in the chapel by the class of 1976 who were among his first students at Nashotah) also includes a miniature image of the Bishop and his wife Joan. Ramsey Hall at Nashotah House was named in his honor, and is a residence for students and families. The Board of Directors of Nashotah House also presents, from time to time, the Michael Ramsey award for distinguished mission or ecumenical service in the Anglican Communion.

Ramsey's funeral was held inCanterbury Cathedralon 3 May. He was cremated and his ashes buried in the cloister garden at the cathedral, not far from the grave ofWilliam Temple.His wife's ashes were also buried there. On the memorial stone are inscribed words fromSt Irenaeus:"The Glory of God is the living man; And the life of man is the vision of God." A side chapel at Canterbury Cathedral was subsequently dedicated to Ramsey's memory, situated next to a similar memorial chapel to Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher.[2]Ramsey had no children. Lady Ramsey died on 17 February 1995 and was buried alongside her husband.

Honours[edit]

Ramsey received numerous honours, he was an honorary fellow of Magdalene College and Selwyn College, Cambridge, and of Merton College, Keble College, and St Cross College, Oxford. He was made an honorary master of the bench, Inner Temple in 1962; was a trustee of the British Museum from 1963 to 1969; and made an honorary Fellow of the British Academy in 1983. He held honorary degrees from Durham, Leeds, Edinburgh, Cambridge, Hull, Manchester, London, Oxford, Kent, and Keele and from a number of overseas universities.”[23]

Legacy[edit]

Dr Sam Brewitt-Taylor, a historian at Lincoln College, University of Oxford,[25]holds that “there is much more historical and theoretical work to be done before Ramsey’s legacy can be properly ascertained.”[26]

Ramsey's name has been given toRamsey House,a residence ofSt Chad's College,University of Durham.He was a Fellow and Governor of the college (resident for a period) and he regularly worshipped and presided at the college's daily Eucharist. A building is also named after him atCanterbury Christ Church University.AhouseatTenison's Schoolis named in his honour. He also gave his name to the former Archbishop Michael Ramsey Technology College (from September 2007St Michael and All Angels Church of England Academy) in Farmers' Road,Camberwell,South East London.[27]

An annual Michael Ramsey Lecture on an appropriate theological topic is delivered atLittle St Mary's, Cambridgein early November.

Michael Ramsey Prize for theological writing launched in 2005 and awarded every three years.[28]

Items found in River Wear[edit]

In October 2009 it was reported byMaev Kennedythat two divers had found a number of gold and silver items in theRiver WearinDurhamwhich were subsequently discovered to have come from Ramsey's personal collection, including items presented to him from dignitaries around the world while he was Archbishop of Canterbury. It is unclear how they came to be in the river. The divers were licensed by the dean and chapter of the cathedral as the owners of the land around the stretch of the river where the items were found. The current legal ownership of the items is yet to be determined. The cathedral was planning an exhibition relating to Ramsey's life in 2010 and a new stained-glass window dedicated to him by artistTom Denny.[29]

The two amateur divers, brothers Gary and Trevor Bankhead, found a total of 32 religious artefacts in theRiver Wearin Durham during a full underwater survey of the area aroundPrebends Bridge.The underwater survey commenced in April 2007 and took two and half years to complete. The finds were individually handed over to the resident archaeologist fromDurham Cathedralto formally record where and when they were found.[30]

Works[edit]

Books

- The Gospel and the Catholic Church(1936)

- The Resurrection of Christ(1945)

- The Glory of God and the Transfiguration of Christ(1949)

- F. D. Maurice and the Conflicts of Modern Theology(1951)

- Durham Essays and Addresses(1956)

- From Gore to Temple(1960)

- Introducing the Christian Faith(1961)

- Image Old and New(1963)

- Canterbury Essays and Addresses(1964)

- Sacred and Secular(1965) (Scott Holland Memorial Lectures,1964)

- God, Christ and the World(1969)

- The Future of the Christian Churchwith Cardinal Suenens (1971)

- The Christian Priest Today(1972)

- Canterbury Pilgrim(1974)

- Holy Spirit(1977)

- Jesus and the Living Past(1980)

- Be Still and Know(1982)

- The Anglican Spirit,ed. Dale D. Coleman (1991/2004)

Works online

- “Faith and Society: an Address to the Church Union School of Sociology, 1955"

- “Unity, Truth and Holiness” (no date).

- “Constantinople and Canterbury: A Lecture in the University of Athens" (1962)

- “Sermons Preached by the Most Reverend and Right Honorable Arthur Michael Ramsey, Lord Archbishop of Canterbury in New York City, 1962.”

- “Sermon Preached at Canterbury Cathedral” 1968.

- “Address by the Archbishop of Canterbury to the meeting of the Joint Anglican/Orthodox Steering Committee at Lambeth, 1974.”

- “Charles C. Grafton, Bishop and Theologian,” Lecture at Nashotah House Theological Seminary, 1967.

References[edit]

- ^ab"Michael Ramsey, Baron Ramsey of Canterbury".Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica Academic(Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016. Web).

- ^abcdefghijklmnopqrWilkinson, Alan. "Ramsey, (Arthur) Michael, Baron Ramsey of Canterbury (1904–1988)".Oxford Dictionary of National Biography(online ed.). Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40002.(Subscription orUK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^Henderson, R. J. (1981).A History of King's College Choir School Cambridge.King's College Choir School. p. 42.ISBN978-0950752808.

- ^Comerford, Patrick."Where part of Salvation is for sale at £2 and Oliver Cromwell is among the saints".Retrieved18 October2019.

- ^"A Field Guide to the English Clergy' Butler-Gallie, F p. 103: London, Oneworld Publications, 2018ISBN9781786074416

- ^Coleman, Dale (2019).Revelation: The Education of a Priest.Wipf and Stock. pp. 171–180.

- ^Alec R. Vidler,Scenes From a Clerical Life: an Autobiography(Collins, 1977), 102.

- ^abDouglas Dales, editor,Glory Descending: Michael Ramsey and His Writings,(Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2005), xxii.

- ^"Ramsey of Canterbury, Arthur Michael Ramsey, Baron".

- ^"Index entry".FreeBMD.Office for National Statistics.Retrieved8 June2023.

- ^Webster, Alan (18 February 1995)."Obituary:Joan Ramsey".The Independent.Archivedfrom the original on 14 May 2022.

- ^"Consecration of the new Bishop of Durham".Church Times.No. 4678. 3 October 1952. p. 693.ISSN0009-658X.Retrieved26 December2016– via UK Press Online archives.

- ^"Toledo Blade – Google News Archive Search".news.google.com.Retrieved18 October2019.

- ^abcd"Arthur Michael Ramsey: Life and Times, by John Macquarrie (1990)".anglicanhistory.org.

- ^abcdPeter John Moses,History Guide Book: Archbishops of Canterbury(Evangelical Bible College of Western Australia, 2009), 47–48.

- ^Allen, John L. Jr. (10 October 2003)."Word From Rome: No Nobel of John Paul; Catholics, Anglicans determined to keep talking; An interview with Cardinal Theodore McCarrick; Personnel changes in the curia".National Catholic Reporter.Vol. 3, no. 7.Retrieved8 June2023.

- ^"Common Declaration of Pope Paul VI and Archbishop Michael Ramsey".www.vatican.va.

- ^abcdefHevesi, Dennis (24 April 1988)."Lord Ramsey, 83, Dies in Britain; Former Archbishop of Canterbury".The New York Times.

- ^Ramsey, Michael (2004).The Anglican Spirit.Church Publications. pp. xi–xiii.ISBN978-1-59628-004-5.

- ^Chadwick, Owen (1990).Michael Ramsey: A Life.Oxford. pp.23–24.ISBN0-19-826189-6.

- ^"28 Oct 1965, Page 24 - The Akron Beacon Journal at Newspapers.com".Newspapers.com.Retrieved14 March2021.

- ^"Primate's last consecration".Church Times.No. 5828. 25 October 1974. p. 1.ISSN0009-658X.Retrieved27 August2019– via UK Press Online archives.

- ^ab"Arthur Michael Ramsey Baron Ramsey Of Canterbury".www.encyclopedia.com.Retrieved18 October2019.

- ^"Durham World Heritage Site".Durham World Heritage Site.Durham Cathedral.Retrieved5 May2023.

- ^"History".www.lincoln.ox.ac.uk.Retrieved18 October2019.

- ^Dr Sam Brewitt-Taylor, review ofArchbishop Ramsey: The Shape of the Church,(review no. 1884) DOI: 10.14296/RiH/2014/1884 Date accessed: 17 March 2016.

- ^Welcome from the Executive Principal, St. Michael and All Angels Academy newsletter, August 2007Archived2 December 2007 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Michael Ramsey Prize".Michael Ramsey Prize.Archbishop of Canterbury. Archived fromthe originalon 1 May 2023.Retrieved12 July2023.

- ^Kennedy, Maev (22 October 2009)."Durham Cathedral divers discover gold and silver treasure trove in riverbed".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved8 February2023.

- ^Stokes, Paul (23 October 2009)."Archbishop's treasure found in river".The Daily Telegraph.ISSN0307-1235.Retrieved18 October2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Owen Chadwick.Michael Ramsey: A Life.Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990.ISBN0-19-826189-6

- Dales, Douglas J., 'Glory – the Spiritual Theology of Michael Ramsey(Canterbury Press, Norwich, 2003)

- Dales, Douglas J.,(ed. with Geoffrey Rowell, John Habgood, & Rowan Williams) 'Glory Descending – Michael Ramsey and His Writings(Canterbury Press, Norwich/Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 2005)

- Jared C. Cramer.Safeguarded by Glory: Michael Ramsey's Ecclesiology and the Struggles of Contemporary Anglicanism.Lexington Books, 2010.ISBN0-7391-4271-2

- Michael De-la-Noy,Michael Ramsey: A Portrait.HarperCollins 1990.ISBN0-00-627567-2

- J.B. Simpson.The Hundredth Archbishop of Canterbury.New York, 1962.

- Christopher Martin (ed.),Great Christian Centuries to Come. Essays in honour of A. M. RamseyLondon, 1974

- Robin Gill and Lorna Kendall (eds),Michael Ramsey as TheologianLondon, 1995

- Peter Webster,Archbishop Ramsey. The shape of the church.Farnham: Ashgate (now Routledge), 2015.

- Michael Ramsey,The Anglican Spirit,edited, annotated, and introduced by Dale Coleman, Cowley Publications,1991. Reissued by Church Publications, 2004, as a Seabury Classic, with a Foreword by Archbishop Rowan Williams.

External links[edit]

- 1904 births

- 1988 deaths

- People educated at Sandroyd School

- 20th-century Anglican archbishops

- Academics of Durham University

- English Anglican theologians

- Alumni of Magdalene College, Cambridge

- Alumni of Ripon College Cuddesdon

- Regius Professors of Divinity (University of Cambridge)

- Anglo-Catholic bishops

- Archbishops of Canterbury

- Archbishops of York

- Bishops of Durham

- Crossbench life peers

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Nashotah House faculty

- People educated at Repton School

- Ordained peers

- Clergy from Cambridge

- Presidents of the Cambridge Union

- Burials at Canterbury Cathedral

- 20th-century English theologians

- English Anglo-Catholics

- Anglo-Catholic theologians

- Staff of Lincoln Theological College

- Honorary Fellows of the British Academy

- Life peers created by Elizabeth II

- 20th-century Anglican theologians

- Ramsey family