Austroasiatic languages

| Austroasiatic | |

|---|---|

| Austro-Asiatic | |

| Geographic distribution | Southeast,SouthandEast Asia |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primarylanguage families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Austroasiatic |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-5 | aav |

| Glottolog | aust1305(Austroasiatic) |

| |

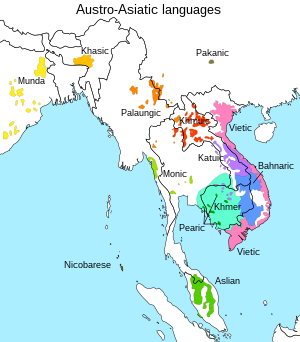

TheAustroasiatic languages[note 1](/ˌɒstroʊ.eɪʒiˈætɪk,ˌɔː-/OSS-troh-ay-zhee-AT-ik, AWSS-) are a largelanguage familyspoken throughoutMainland Southeast Asia,South AsiaandEast Asia.These languages are natively spoken by the majority of the population inVietnamandCambodia,and by minority populations scattered throughout parts ofThailand,Laos,India,Myanmar,Malaysia,Bangladesh,Nepal,andsouthern China.Approximately 117 million people speak an Austroasiatic language, of which more than two-thirds areVietnamesespeakers.[1]Of the Austroasiatic languages, onlyVietnamese,Khmer,andMonhave lengthy, established presences in the historical record. Only two are presently considered to be thenational languagesof sovereign states: Vietnamese in Vietnam, and Khmer in Cambodia. The Mon language is a recognized indigenous language in Myanmar and Thailand, while theWa languageis a "recognized national language" in the de facto autonomousWa Statewithin Myanmar.Santaliis one ofthe 22 scheduled languages of India.The remainder of the family's languages are spoken by minority groups and have no official status.

Ethnologueidentifies 168 Austroasiatic languages. These form thirteen established families (plus perhapsShompen,which is poorly attested, as a fourteenth), which have traditionally been grouped into two, as Mon–Khmer,[2]andMunda.However, one recent classification posits three groups (Munda, Mon-Khmer, andKhasi–Khmuic),[3]while another has abandoned Mon–Khmer as a taxon altogether, making it synonymous with the larger family.[4]

Austroasiatic languages appear to be the extantautochthonous languagesin mainland Southeast Asia, with the neighboringKra–Dai,Hmong-Mien,Austronesian,andSino-Tibetan languageshaving arrived via later migrations.[5]

Etymology[edit]

The nameAustroasiaticwas coined byWilhelm Schmidt(German:austroasiatisch) based onauster,theLatinword for "South" (but idiosyncratically used by Schmidt to refer to the southeast), and "Asia".[6]Despite the literal meaning of its name, only three Austroasiatic branches are actually spoken in South Asia:Khasic,Munda,andNicobarese.

Typology[edit]

Regarding word structure, Austroasiatic languages are well known for having an iambic"sesquisyllabic"pattern, with basic nouns and verbs consisting of an initial, unstressed, reducedminor syllablefollowed by a stressed, full syllable.[7]This reduction of presyllables has led to a variety of phonological shapes of the same original Proto-Austroasiatic prefixes, such as the causative prefix, ranging from CVC syllables to consonant clusters to single consonants among the modern languages.[8]As for word formation, most Austroasiatic languages have a variety of derivational prefixes, many haveinfixes,but suffixes are almost completely non-existent in most branches except Munda, and a few specialized exceptions in other Austroasiatic branches.[9]

The Austroasiatic languages are further characterized as having unusually large vowel inventories and employing some sort ofregistercontrast, either betweenmodal(normal) voice andbreathy(lax) voice or between modal voice andcreaky voice.[10]Languages in the Pearic branch and some in the Vietic branch can have a three- or even four-way voicing contrast.

However, some Austroasiatic languages have lost the register contrast by evolving more diphthongs or in a few cases, such as Vietnamese,tonogenesis.Vietnamese has been so heavily influenced by Chinese that its original Austroasiatic phonological quality is obscured and now resembles that of South Chinese languages, whereas Khmer, which had more influence from Sanskrit, has retained a more typically Austroasiatic structure.

Proto-language[edit]

Much work has been done on the reconstruction ofProto-Mon–KhmerinHarry L. Shorto'sMon–Khmer Comparative Dictionary.Little work has been done on theMunda languages,which are not well documented. With their demotion from a primary branch, Proto-Mon–Khmer becomes synonymous with Proto-Austroasiatic. Paul Sidwell (2005) reconstructs the consonant inventory of Proto-Mon–Khmer as follows:[11]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | *p | *t | *c | *k | *ʔ |

| voiced | *b | *d | *ɟ | *ɡ | ||

| implosive | *ɓ | *ɗ | *ʄ | |||

| Nasal | *m | *n | *ɲ | *ŋ | ||

| Liquid | *w | *l,*r | *j | |||

| Fricative | *s | *h | ||||

This is identical to earlier reconstructions except for*ʄ.*ʄis better preserved in theKatuic languages,which Sidwell has specialized in.

Internal classification[edit]

Linguists traditionally recognize two primary divisions of Austroasiatic: theMon–Khmer languagesofSoutheast Asia,Northeast Indiaand theNicobar Islands,and theMunda languagesofEastandCentral Indiaand parts ofBangladeshandNepal.However, no evidence for this classification has ever been published.

Each of the families that is written in boldface type below is accepted as a valid clade.[clarification needed]By contrast, the relationshipsbetweenthese families within Austroasiatic are debated. In addition to the traditional classification, two recent proposals are given, neither of which accepts traditional "Mon–Khmer" as a valid unit. However, little of the data used for competing classifications has ever been published, and therefore cannot be evaluated by peer review.

In addition, there are suggestions that additional branches of Austroasiatic might be preserved in substrata ofAcehnesein Sumatra (Diffloth), theChamic languagesof Vietnam, and theLand Dayak languagesof Borneo (Adelaar 1995).[12]

Diffloth (1974)[edit]

Diffloth's widely cited original classification, now abandoned by Diffloth himself, is used inEncyclopædia Britannicaand—except for the breakup of Southern Mon–Khmer—inEthnologue.

- Austro‑Asiatic

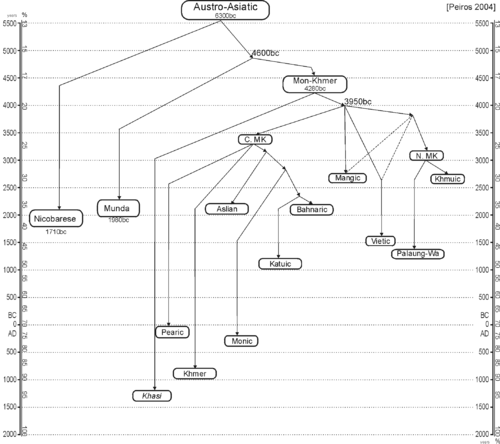

Peiros (2004)[edit]

Peiros is alexicostatisticclassification, based on percentages of shared vocabulary. This means that languages can appear to be more distantly related than they actually are due tolanguage contact.Indeed, when Sidwell (2009) replicated Peiros's study with languages known well enough to account for loans, he did not find the internal (branching) structure below.

Diffloth (2005)[edit]

Difflothcompares reconstructions of various clades, and attempts to classify them based on shared innovations, though like other classifications the evidence has not been published. As a schematic, we have:

| Austro‑Asiatic | |

Or in more detail,

- Austro‑Asiatic

- Munda languages(India)

- Koraput:7 languages

- Core Munda languages

- Kharian–Juang:2 languages

- North Munda languages

- Korku

- Kherwarian:12 languages

- Khasi–Khmuic languages(Northern Mon–Khmer)

- Nuclear Mon–Khmer languages

- Khmero-Vietic languages (Eastern Mon–Khmer)

- Vieto-Katuic languages?[13]

- Vietic:10 languages of Vietnam and Laos, includingMuongandVietnamese,which has the most speakers of any Austroasiatic language.

- Katuic:19 languages of Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand.

- Khmero-Bahnaric languages

- Vieto-Katuic languages?[13]

- Nico-Monic languages (Southern Mon–Khmer)

- Nicobarese:6 languages of theNicobar Islands,a territory of India.

- Asli-Monic languages

- Aslian:19 languages of peninsular Malaysia and Thailand.

- Monic:2 languages, theMon languageof Burma and theNyahkur languageof Thailand.

- Khmero-Vietic languages (Eastern Mon–Khmer)

- Munda languages(India)

Sidwell (2009–2015)[edit]

Paul Sidwell(2009), in alexicostatisticalcomparison of 36 languages which are well known enough to exclude loanwords, finds little evidence for internal branching, though he did find an area of increased contact between the Bahnaric and Katuic languages, such that languages of all branches apart from the geographically distantMundaand Nicobarese show greater similarity to Bahnaric and Katuic the closer they are to those branches, without any noticeable innovations common to Bahnaric and Katuic.

He therefore takes the conservative view that the thirteen branches of Austroasiatic should be treated as equidistant on current evidence. Sidwell &Blench(2011) discuss this proposal in more detail, and note that there is good evidence for a Khasi–Palaungic node, which could also possibly be closely related to Khmuic.[5]

If this would the case, Sidwell & Blench suggest that Khasic may have been an early offshoot of Palaungic that had spread westward. Sidwell & Blench (2011) suggestShompenas an additional branch, and believe that a Vieto-Katuic connection is worth investigating. In general, however, the family is thought to have diversified too quickly for a deeply nested structure to have developed, since Proto-Austroasiatic speakers are believed by Sidwell to have radiated out from the centralMekongriver valley relatively quickly.

Subsequently, Sidwell (2015a: 179)[14]proposed thatNicobaresesubgroups withAslian,just as how Khasian and Palaungic subgroup with each other.

Austroasiatic:Mon–Khmer

|

|

A subsequent computational phylogenetic analysis (Sidwell 2015b)[15]suggests that Austroasiatic branches may have a loosely nested structure rather than a completely rake-like structure, with an east–west division (consisting of Munda, Khasic, Palaungic, and Khmuic forming a western group as opposed to all of the other branches) occurring possibly as early as 7,000 years before present. However, he still considers the subbranching dubious.

Integrating computational phylogenetic linguistics with recent archaeological findings, Paul Sidwell (2015c)[16]further expanded his Mekong riverine hypothesis by proposing that Austroasiatic had ultimately expanded intoIndochinafrom theLingnanarea ofsouthern China,with the subsequent Mekong riverine dispersal taking place after the initial arrival of Neolithic farmers from southern China.

Sidwell (2015c) tentatively suggests that Austroasiatic may have begun to split up 5,000 years B.P. during theNeolithic transitionera ofmainland Southeast Asia,with all the major branches of Austroasiatic formed by 4,000 B.P. Austroasiatic would have had two possible dispersal routes from the western periphery of thePearl Riverwatershed ofLingnan,which would have been either a coastal route down the coast of Vietnam, or downstream through theMekong RiverviaYunnan.[16]Both the reconstructed lexicon of Proto-Austroasiatic and the archaeological record clearly show that early Austroasiatic speakers around 4,000 B.P. cultivated rice andmillet,kept livestock such as dogs, pigs, and chickens, and thrived mostly in estuarine rather than coastal environments.[16]

At 4,500 B.P., this "Neolithic package" suddenly arrived in Indochina from the Lingnan area without cereal grains and displaced the earlier pre-Neolithic hunter-gatherer cultures, with grain husks found in northern Indochina by 4,100 B.P. and in southern Indochina by 3,800 B.P.[16]However, Sidwell (2015c) found that iron is not reconstructable in Proto-Austroasiatic, since each Austroasiatic branch has different terms for iron that had been borrowed relatively lately from Tai, Chinese, Tibetan, Malay, and other languages.

During theIron Ageabout 2,500 B.P., relatively young Austroasiatic branches in Indochina such asVietic,Katuic,Pearic,andKhmerwere formed, while the more internally diverseBahnaricbranch (dating to about 3,000 B.P.) underwent more extensive internal diversification.[16]By the Iron Age, all of the Austroasiatic branches were more or less in their present-day locations, with most of the diversification within Austroasiatic taking place during the Iron Age.[16]

Paul Sidwell (2018)[17]considers the Austroasiatic language family to have rapidly diversified around 4,000 years B.P. during the arrival of rice agriculture in Indochina, but notes that the origin of Proto-Austroasiatic itself is older than that date. The lexicon of Proto-Austroasiatic can be divided into an early and late stratum. The early stratum consists of basic lexicon including body parts, animal names, natural features, and pronouns, while the names of cultural items (agriculture terms and words for cultural artifacts, which are reconstructible in Proto-Austroasiatic) form part of the later stratum.

Roger Blench(2017)[18]suggests that vocabulary related to aquatic subsistence strategies (such as boats, waterways, river fauna, and fish capture techniques) can be reconstructed for Proto-Austroasiatic. Blench (2017) finds widespread Austroasiatic roots for 'river, valley', 'boat', 'fish', 'catfish sp.', 'eel', 'prawn', 'shrimp' (Central Austroasiatic), 'crab', 'tortoise', 'turtle', 'otter', 'crocodile', 'heron, fishing bird', and 'fish trap'. Archaeological evidence for the presence of agriculture in northernIndochina(northern Vietnam, Laos, and other nearby areas) dates back to only about 4,000 years ago (2,000 BC), with agriculture ultimately being introduced from further up to the north in the Yangtze valley where it has been dated to 6,000 B.P.[18]

Sidwell (2022)[19][20]proposes that the locus of Proto-Austroasiatic was in theRed River Deltaarea about 4,000-4,500 years before present, instead of the Middle Mekong as he had previously proposed. Austroasiatic dispersed coastal maritime routes and also upstream through river valleys. Khmuic, Palaungic, and Khasic resulted from a westward dispersal that ultimately came from the Red Valley valley. Based on their current distributions, about half of all Austroasiatic branches (including Nicobaric and Munda) can be traced to coastal maritime dispersals.

Hence, this points to a relatively late riverine dispersal of Austroasiatic as compared toSino-Tibetan,whose speakers had a distinct non-riverine culture. In addition to living an aquatic-based lifestyle, early Austroasiatic speakers would have also had access to livestock, crops, and newer types of watercraft. As early Austroasiatic speakers dispersed rapidly via waterways, they would have encountered speakers of older language families who were already settled in the area, such as Sino-Tibetan.[18]

Sidwell (2018)[edit]

Sidwell (2018)[21](quoted in Sidwell 2021[22]) gives a more nested classification of Austroasiatic branches as suggested by his computational phylogenetic analysis of Austroasiatic languages using a 200-word list. Many of the tentative groupings are likelylinkages.PakanicandShompenwere not included.

| Austroasiatic | |

Possible extinct branches[edit]

Roger Blench(2009)[23]also proposes that there might have been other primary branches of Austroasiatic that are now extinct, based onsubstrateevidence in modern-day languages.

- Pre-Chamiclanguages(the languages of coastal Vietnam before the Chamic migrations). Chamic has various Austroasiatic loanwords that cannot be clearly traced to existing Austroasiatic branches (Sidwell 2006, 2007).[24][25]Larish (1999)[26]also notes thatMoklenic languagescontain many Austroasiatic loanwords, some of which are similar to the ones found in Chamic.

- Acehnesesubstratum(Sidwell 2006).[24]Acehnese has many basic words that are of Austroasiatic origin, suggesting that either Austronesian speakers have absorbed earlier Austroasiatic residents in northern Sumatra, or that words might have been borrowed from Austroasiatic languages in southern Vietnam – or perhaps a combination of both. Sidwell (2006) argues that Acehnese and Chamic had often borrowed Austroasiatic words independently of each other, while some Austroasiatic words can be traced back to Proto-Aceh-Chamic. Sidwell (2006) accepts that Acehnese and Chamic are related, but that they had separated from each other before Chamic had borrowed most of its Austroasiatic lexicon.

- Borneansubstrate languages(Blench 2010).[27]Blench cites Austroasiatic-origin words in modern-day Bornean branches such asLand Dayak(Bidayuh,Dayak Bakatiq,etc.),Dusunic(Central Dusun,Visayan,etc.),Kayan,andKenyah,noting especially resemblances withAslian.As further evidence for his proposal, Blench also cites ethnographic evidence such as musical instruments in Borneo shared in common with Austroasiatic-speaking groups in mainland Southeast Asia. Adelaar (1995)[28]has also noticed phonological and lexical similarities betweenLand DayakandAslian.Kaufman (2018) presents dozens of lexical comparisons showing similarities between various Bornean and Austroasiatic languages.[29]

- Lepchasubstratum( "Rongic").[30]Many words of Austroasiatic origin have been noticed inLepcha,suggesting aSino-Tibetansuperstrate laid over an Austroasiatic substrate. Blench (2013) calls this branch "Rongic"based on the Lepcha autonymRóng.

Other languages with proposed Austroasiatic substrata are:

- Jiamao,based on evidence from the register system of Jiamao, aHlailanguage (Thurgood 1992).[31]Jiamao is known for its highly aberrant vocabulary in relation to otherHlai languages.

- Kerinci:van Reijn (1974)[32]notes that Kerinci, aMalayiclanguage of centralSumatra,shares many phonological similarities with Austroasiatic languages, such assesquisyllabicword structure and vowel inventory.

John Peterson (2017)[33]suggests that "pre-Munda"(" proto- "in regular terminology) languages may have once dominated the easternIndo-Gangetic Plain,and were then absorbed by Indo-Aryan languages at an early date as Indo-Aryan spread east. Peterson notes that easternIndo-Aryan languagesdisplay many morphosyntactic features similar to those of Munda languages, while western Indo-Aryan languages do not.

Writing systems[edit]

Other than Latin-based alphabets, many Austroasiatic languages are written with theKhmer,Thai,Lao,andBurmesealphabets. Vietnamese divergently had an indigenous script based on Chinese logographic writing. This has since been supplanted by the Latin alphabet in the 20th century. The following are examples of past-used alphabets or current alphabets of Austroasiatic languages.

- Chữ Nôm[34]

- Khmer alphabet[35]

- Khom script(used for a short period in the early 20th century for indigenous languages in Laos)

- Old Mon script

- Mon script

- Pahawh Hmongwas once used to writeKhmu,under the name "Pahawh Khmu"

- Tai Le(Palaung,Blang)

- Tai Tham(Blang)

- Ol Chiki alphabet(Santalialphabet)[36]

- Mundari Bani(Mundarialphabet)

- Warang Citi(Hoalphabet)[37]

- Ol Onal(Bhumijalphabet)

- Sorang Sompeng alphabet(Soraalphabet)[38]

External relations[edit]

Austric languages[edit]

Austroasiatic is an integral part of the controversialAustric hypothesis,which also includes theAustronesian languages,and in some proposals also theKra–Dai languagesand theHmong–Mien languages.[39]

Hmong-Mien[edit]

Several lexical resemblancesare found between the Hmong-Mien and Austroasiatic language families (Ratliff 2010), some of which had earlier been proposed byHaudricourt(1951). This could imply a relation or early language contact along theYangtze.[40]

According to Cai (et al. 2011),Hmong–Mienpeople aregeneticallyrelated to Austroasiatic speakers, and their languages were heavily influenced bySino-Tibetan,especiallyTibeto-Burman languages.[41]

Indo-Aryan languages[edit]

It is suggested that the Austroasiatic languages have some influence onIndo-Aryan languagesincludingSanskritand middle Indo-Aryan languages. Indian linguistSuniti Kumar Chatterjipointed that a specific number of substantives in languages such asHindi,PunjabiandBengaliwere borrowed fromMunda languages.Additionally, French linguistJean Przyluskisuggested a similarity between the tales from the Austroasiatic realm and the Indian mythological stories ofMatsyagandha(Satyavati fromMahabharata) and theNāgas.[42]

Austroasiatic migrations and archaeogenetics[edit]

Mitsuru Sakitanisuggests thatHaplogroup O1b1,which is common in Austroasiatic people and some other ethnic groups insouthern China,and haplogroup O1b2, which is common in today'sJapaneseandKoreans,are the carriers of early rice agriculture from southern China.[43]Another study suggests that the haplogroup O1b1 is the major Austroasiatic paternal lineage and O1b2 the "para-Austroasiatic" lineage of theKoreansandYayoi people.[44]

A full genomic study by Lipson et al. (2018) identified a characteristic lineage that can be associated with the spread of Austroasiatic languages in Southeast Asia and which can be traced back to remains of Neolithic farmers fromMán Bạc(c. 2000 BCE) in theRed River Deltain northern Vietnam, and to closely relatedBan Chiangand Vat Komnou remains inThailandandCambodiarespectively. This Austroasiatic lineage can be modeled as a sister group of theAustronesian peopleswith significant admixture (ca. 30%) from a deeply diverging eastern Eurasian source (modeled by the authors as sharing some genetic drift with theOnge,a modernAndamanese hunter-gatherer group) and which is ancestral to modern Austroasiatic-speaking groups of Southeast Asia such as theMlabriand theNicobarese,and partially to the Austroasiatic Munda-speaking groups of South Asia (e.g.theJuang). Significant levels of Austroasiatic ancestry were also found in Austronesian-speaking groups ofSumatra,Java,andBorneo.[45][note 3]Austroasiatic-speaking groups in southernChina(such as theWaandBlanginYunnan) predominatly carry the same Mainland Southeast Asian Neolithic farmer ancestry, but with additional geneflow from northern and southern East Asian lineages that can be associated with the spread ofTibeto-BurmanandKra-Dai languages,respectively.[47]

Migration into India[edit]

According to Chaubey et al., "Austro-Asiatic speakers in India today are derived from dispersal fromSoutheast Asia,followed by extensive sex-specific admixture with local Indian populations. "[48]According to Riccio et al., theMunda peoplesare likely descended from Austroasiatic migrants from Southeast Asia.[49]

According to Zhang et al., Austroasiatic migrations from Southeast Asia into India took place after theLast Glacial Maximum,circa 10,000 years ago.[50]Arunkumar et al., suggest Austroasiatic migrations from Southeast Asia occurred into Northeast India 5.2 ± 0.6 kya and into East India 4.3 ± 0.2 kya.[51]

Notes[edit]

- ^Sometimes alsoAustro-AsiaticorAustroasian

- ^Earlier classifications by Sidwell had lumpedMangandPakanictogether into aMangicsubgroup, but Sidwell currently considers Mang and Pakanic to each be independent branches of Austroasiatic.

- ^Austroasiatic-related ancestry had been detected before also in other ethnic groups of theSunda Islands(e.g.Javanese,Sundanese,andManggarai).[46]

References[edit]

- ^"Austroasiatic".www.languagesgulper.com.Archivedfrom the original on 29 March 2019.Retrieved15 October2017.

- ^Bradley (2012) notes,MK in the wider sense including the Munda languages of eastern South Asia is also known as Austroasiatic.

- ^Diffloth 2005

- ^Sidwell 2009

- ^abSidwell, Paul, and Roger Blench. 2011. "The Austroasiatic Urheimat: the Southeastern Riverine HypothesisArchived18 November 2017 at theWayback Machine."Enfield, NJ (ed.)Dynamics of Human Diversity,317–345. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- ^Schmidt, Wilhelm (1906). "Die Mon–Khmer-Völker, ein Bindeglied zwischen Völkern Zentralasiens und Austronesiens ('[The Mon–Khmer Peoples, a Link between the Peoples of Central Asia and Austronesia')".Archiv für Anthropologie.5:59–109.

- ^Alves 2014,p. 524.

- ^Alves 2014,p. 526.

- ^Alves 2014, 2015

- ^Diffloth, Gérard (1989)."Proto-Austroasiatic creaky voice."Archived25 August 2015 at theWayback Machine

- ^Sidwell (2005),p. 196.

- ^Roger Blench,2009. Are there four additional unrecognised branches of Austroasiatic?Presentation at ICAAL-4, Bangkok, 29–30 October. Summarized in Sidwell and Blench (2011).

- ^abSidwell (2005) casts doubt on Diffloth's Vieto-Katuic hypothesis, saying that the evidence is ambiguous, and that it is not clear where Katuic belongs in the family.

- ^Sidwell, Paul. 2015a. "Austroasiatic classification." In Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015).The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages.Leiden: Brill.

- ^Sidwell, Paul. 2015b.A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the Austroasiatic languagesArchived15 December 2017 at theWayback Machine.Presented at Diversity Linguistics: Retrospect and Prospect, 1–3 May 2015 (Leipzig, Germany), Closing conference of the Department of Linguistics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ^abcdefSidwell, Paul. 2015c.Phylogeny, innovations, and correlations in the prehistory of Austroasiatic.Paper presented at the workshopIntegrating inferences about our past: new findings and current issues in the peopling of the Pacific and South East Asia,22–23 June 2015, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany.

- ^Sidwell, Paul. 2018.Austroasiatic deep chronology and the problem of cultural lexicon.Paper presented at the 28th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, held 17–19 May 2018 in Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

- ^abcBlench, Roger. 2017.Waterworld: lexical evidence for aquatic subsistence strategies in AustroasiaticArchived14 December 2017 at theWayback Machine.Presented at ICAAL 7, Kiel, Germany.

- ^Sidwell, Paul (28 January 2022). Alves, Mark; Sidwell, Paul (eds.)."Austroasiatic Dispersal: the AA" Water-World "Extended".Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society: Papers from the 30th Conference of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (2021).15(3): 95–111.doi:10.5281/zenodo.5773247.ISSN1836-6821.Archivedfrom the original on 30 January 2022.Retrieved14 February2022.

- ^Sidwell, Paul. 2021.Austroasiatic Dispersal: the AA "Water-World" ExtendedArchived17 February 2022 at theWayback Machine.SEALS 2021Archived16 December 2021 at theWayback Machine.(Video)Archived17 February 2022 at theWayback Machine

- ^Sidwell, Paul. 2018.Austroasiatic deep chronology and the problem of cultural lexiconArchived31 March 2023 at theWayback Machine.Paper presented at the 28th Annual Meeting of theSoutheast Asian Linguistics Society.Kaohsiung,Taiwan. (accessed 16 December 2020).

- ^Sidwell, Paul (9 August 2021). "Classification of MSEA Austroasiatic languages".The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia.De Gruyter. pp. 179–206.doi:10.1515/9783110558142-011.ISBN9783110558142.S2CID242599355.

- ^Blench, Roger. 2009. "Are there four additional unrecognised branches of Austroasiatic?Archived3 March 2016 at theWayback Machine."

- ^abSidwell, Paul. 2006. "Dating the Separation of Acehnese and Chamic By Etymological Analysis of the Aceh-Chamic LexiconArchived8 November 2014 at theWayback Machine."In TheMon-Khmer Studies Journal,36: 187–206.

- ^Sidwell, Paul. 2007. "The Mon-Khmer Substrate in Chamic: Chamic, Bahnaric and Katuic ContactArchived16 June 2015 at theWayback Machine."In SEALS XII Papers from the 12th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2002, edited by Ratree Wayland et al.. Canberra, Australia, 113-128. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University.

- ^Larish, Michael David. 1999.The Position of Moken and Moklen Within the Austronesian Language Family.Doctoral dissertation, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa.

- ^Blench, Roger. 2010. "Was there an Austroasiatic Presence in Island Southeast Asia prior to the Austronesian Expansion?Archived31 March 2023 at theWayback Machine"InBulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association,Vol. 30.

- ^Adelaar, K.A. 1995.Borneo as a cross-roads for comparative Austronesian linguisticsArchived3 July 2018 at theWayback Machine.In P. Bellwood, J.J. Fox and D. Tryon (eds.), The Austronesians, pp. 81-102. Canberra: Australian National University.

- ^Kaufman, Daniel. 2018.Between mainland and island Southeast Asia: Evidence for a Mon-Khmer presence in Borneo.Ronald and Janette Gatty Lecture Series. Kahin Center for Advanced Research on Southeast Asia, Cornell University. (handoutArchived18 February 2023 at theWayback Machine/slidesArchived18 February 2023 at theWayback Machine)

- ^Blench, Roger. 2013.Rongic: a vanished branch of AustroasiaticArchived9 August 2018 at theWayback Machine.m.s.

- ^Thurgood, Graham. 1992. "The aberrancy of the Jiamao dialect of Hlai: speculation on its origins and historyArchived30 January 2018 at theWayback Machine".In Ratliff, Martha S. and Schiller, E. (eds.),Papers from the First Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society,417–433. Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies.

- ^van Reijn, E. O. (1974). "Some Remarks on the Dialects of North Kerintji: A link with Mon-Khmer Languages."Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society,31, 2: 130–138.JSTOR41492089.

- ^Peterson, John (2017). "The prehistorical spread of Austro-Asiatic in South AsiaArchived11 April 2018 at theWayback Machine".Presented at ICAAL 7, Kiel, Germany.

- ^"Vietnamese Chu Nom script".Omniglot.com.Archivedfrom the original on 2 February 2012.Retrieved11 March2012.

- ^"Khmer/Cambodian alphabet, pronunciation and language".Omniglot.com. Archived fromthe originalon 13 February 2012.Retrieved11 March2012.

- ^"Santali alphabet, pronunciation and language".Omniglot.com.Archivedfrom the original on 5 November 2010.Retrieved11 March2012.

- ^Everson, Michael(19 April 2012)."N4259: Final proposal for encoding the Warang Citi script in the SMP of the UCS"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022.Retrieved20 August2016.

- ^"Sorang Sompeng script".Omniglot.com. 18 June 1936.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2021.Retrieved11 March2012.

- ^Reid, Lawrence A. (2009). "Austric Hypothesis". In Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.).Concise Encyclopaedia of Languages of the World.Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 92–94.

- ^Haudricourt, André-Georges. 1951.Introduction à la phonologie historique des langues miao-yaoArchived22 April 2019 at theWayback Machine[An introduction to the historical phonology of the Miao-Yao languages].Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient44(2). 555–576.

- ^Consortium, the Genographic; Li, Hui; Jin, Li; Huang, Xingqiu; Li, Shilin; Wang, Chuanchao; Wei, Lanhai; Lu, Yan; Wang, Yi (31 August 2011)."Human Migration through Bottlenecks from Southeast Asia into East Asia during Last Glacial Maximum Revealed by Y Chromosomes".PLOS ONE.6(8): e24282.Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624282C.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024282.ISSN1932-6203.PMC3164178.PMID21904623.

- ^Lévi, Sylvain; Przyluski, Jean; Bloch, Jules (1993).Pre-Aryan and Pre-Dravidian in India.Asian Educational Services. p. 4,15.ISBN9788120607729.Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023.Retrieved15 October2020.

- ^Kỳ cốc mãn 『DNA・ khảo cổ ・ ngôn ngữ の học tế nghiên cứu が kỳ す tân ・ nhật bổn liệt đảo sử 』 ( miễn thành xuất bản 2009 niên )

- ^Robbeets, Martine; Savelyev, Alexander (21 December 2017).Language Dispersal Beyond Farming.John Benjamins Publishing Company.ISBN9789027264640.Archivedfrom the original on 31 March 2023.Retrieved15 October2020.

- ^Lipson M, Cheronet O, Mallick S, Rohland N, Oxenham M, Pietrusewsky M, et al. (2018)."Ancient genomes document multiple waves of migration in Southeast Asian prehistory".Science.361(6397): 92–95.Bibcode:2018Sci...361...92L.doi:10.1126/science.aat3188.PMC6476732.PMID29773666.

- ^Lipson, Mark; Loh, Po-Ru; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Ko, Ying-Chin; Stoneking, Mark; Berger, Bonnie; Reich, David (19 August 2014)."Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia".Nature Communications.5:4689.Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4689L.doi:10.1038/ncomms5689.PMC4143916.PMID25137359.

- ^Guo, Jianxin; Wang, Weitao; Zhao, Kai; Li, Guangxing; He, Guanglin; Zhao, Jing; Yang, Xiaomin; Chen, Jinwen; Zhu, Kongyang; Wang, Rui; Ma, Hao (2022)."Genomic insights into Neolithic farming-related migrations in the junction of east and southeast Asia".American Journal of Biological Anthropology.177(2): 328–342.doi:10.1002/ajpa.24434.ISSN2692-7691.S2CID244155341.Archivedfrom the original on 5 January 2022.Retrieved5 January2022.

In our study, we found the sharing of a large amount of ancestry (>50%) among the Vietnam Late Neolithic ancients, Wa_L and Blang_X, indicating the Yunnan Austroasiatic populations had been influenced both linguistically and genetically by the expansion of Austroasiatic groups from mainland SEA.

- ^Chaubey et al. 2010,p. 1013.

- ^Riccio, M. E.; et al. (2011). "The Austroasiatic Munda population from India and Its enigmatic origin: a HLA diversity study".Human Biology.83(3): 405–435.doi:10.3378/027.083.0306.JSTOR41466748.PMID21740156.S2CID39428816.

- ^Zhang 2015.

- ^Arunkumar, G.; et al. (2015)."A late Neolithic expansion of Y chromosomal haplogroup O2a1-M95 from east to west".Journal of Systematics and Evolution.53(6): 546–560.doi:10.1111/jse.12147.S2CID83103649.

Sources[edit]

- Adams, K. L. (1989).Systems of numeral classification in the Mon–Khmer, Nicobarese and Aslian subfamilies of Austroasiatic.Canberra, A.C.T., Australia: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University.ISBN0-85883-373-5

- Alves, Mark J. (2014). "Mon-Khmer". In Rochelle Lieber; Pavel Stekauer (eds.).The Oxford Handbook of Derivational Morphology.Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 520–544.

- Alves, Mark J. (2015). Morphological functions among Mon-Khmer languages: beyond the basics. In N. J. Enfield & Bernard Comrie (eds.),Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia: the state of the art.Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton, 531–557.

- Bradley, David (2012). "Languages and Language Families in ChinaArchived30 April 2017 at theWayback Machine",in Rint Sybesma (ed.),Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics.

- Chakrabarti, Byomkes.(1994).A Comparative Study of Santali and Bengali.

- Chaubey, G.; et al. (2010)."Population Genetic Structure in Indian Austroasiatic Speakers: The Role of Landscape Barriers and Sex-Specific Admixture".Mol Biol Evol.28(2): 1013–1024.doi:10.1093/molbev/msq288.PMC3355372.PMID20978040.

- Diffloth, Gérard.(2005). "The contribution of linguistic palaeontology and Austro-Asiatic". in Laurent Sagart, Roger Blench and Alicia Sanchez-Mazas, eds.The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics.77–80. London: Routledge Curzon.ISBN0-415-32242-1

- Filbeck, D. (1978).T'in: a historical study.Pacific linguistics, no. 49. Canberra: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University.ISBN0-85883-172-4

- Hemeling, K. (1907).Die Nanking Kuanhua.(German language)

- Jenny, Mathias andPaul Sidwell,eds (2015).The Handbook of Austroasiatic LanguagesArchived5 March 2015 at theWayback Machine.Leiden: Brill.

- Peck, B. M., Comp. (1988).An Enumerative Bibliography of South Asian Language Dictionaries.

- Peiros, Ilia. 1998.Comparative Linguistics in Southeast Asia.Pacific Linguistics Series C, No. 142. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Shorto, Harry L. edited by Sidwell, Paul, Cooper, Doug and Bauer, Christian (2006).A Mon–Khmer comparative dictionaryArchived9 August 2018 at theWayback Machine.Canberra: Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics.ISBN0-85883-570-3

- Shorto, H. L.Bibliographies of Mon–Khmer and Tai Linguistics.London oriental bibliographies, v. 2. London: Oxford University Press, 1963.

- Sidwell, Paul(2005)."Proto-Katuic Phonology and the Sub-grouping of Mon–Khmer Languages"(PDF).In Paul Sidwell (ed.).SEALSXV: papers from the 15th meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistic Society.Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.Archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022.Retrieved11 March2020.

- Sidwell, Paul (2009).Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: history and state of the art.LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics. Vol. 76. Munich: Lincom Europa.ISBN978-3-929075-67-0.[permanent dead link]

- Sidwell, Paul (2010)."The Austroasiatic central riverine hypothesis"(PDF).Journal of Language Relationship.4:117–134.Archived(PDF)from the original on 30 January 2022.Retrieved28 October2011.

- van Driem, George. (2007). Austroasiatic phylogeny and the Austroasiatic homeland in light of recent population genetic studies.Mon-Khmer Studies, 37,1–14.

- Zide, Norman H., and Milton E. Barker. (1966)Studies in Comparative Austroasiatic Linguistics,The Hague: Mouton (Indo-Iranian monographs, v. 5.).

- Zhang; et al. (2015)."Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro-Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent".Scientific Reports.5:1548.Bibcode:2015NatSR...515486Z.doi:10.1038/srep15486.PMC4611482.PMID26482917.

Further reading[edit]

- Sidwell, Paul; Jenny, Mathias, eds. (2021).The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia(PDF).De Gruyter.doi:10.1515/9783110558142.hdl:2262/97064.ISBN978-3-11-055814-2.S2CID242359233.Archived(PDF)from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Mann, Noel, Wendy Smith and Eva Ujlakyova. 2009.Linguistic clusters of Mainland Southeast Asia: an overview of the language families.Archived24 March 2019 at theWayback MachineChiang Mai: Payap University.

- Mason, Francis(1854). "The Talaing Language".Journal of the American Oriental Society.4:277, 279–288.JSTOR592280.

- Sidwell, Paul (2013). "Issues in Austroasiatic Classification".Language and Linguistics Compass.7(8): 437–457.doi:10.1111/lnc3.12038.

- Sidwell, Paul. 2016.Bibliography of Austroasiatic linguistics and related resourcesArchived24 March 2019 at theWayback Machine.

- E. K. Brown (ed.) Encyclopedia of Languages and Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier Press.

- Gregory D. S. Anderson and Norman H. Zide. 2002. Issues in Proto-Munda and Proto-Austroasiatic Nominal Derivation: The Bimoraic Constraint. In Marlys A. Macken (ed.) Papers from the 10th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University, South East Asian Studies Program, Monograph Series Press. pp. 55–74.

External links[edit]

- Swadesh lists for Austro-Asiatic languages(from Wiktionary'sSwadesh-list appendix)

- Mon–Khmer.comLectures byPaul Sidwell

- Mon–Khmer Languages ProjectatSEAlang

- Munda Languages ProjectatSEAlang

- RWAAI(Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- RWAAI Digital Archive

- Michel Ferlus's recordings of Mon-Khmer (Austroasiatic) languagesArchived9 February 2019 at theWayback Machine(CNRS)