Morrissey

Morrissey | |

|---|---|

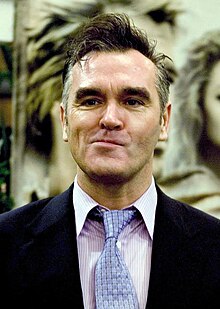

Morrissey in 2005 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Steven Patrick Morrissey |

| Born | 22 May 1959 Davyhulme,Lancashire, England |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Years active | 1976–present |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | morrisseycentral |

Steven Patrick Morrissey(/ˈmɒrɪsi/MORR-iss-ee;born 22 May 1959), knownmononymouslyasMorrissey,is an English singer and songwriter. He came to prominence as the frontman and lyricist of rock bandthe Smiths,who were active from 1982 to 1987. Since then, he has pursued a successful solo career. Morrissey's music is characterised by hisbaritonevoice and distinctive lyrics with recurring themes of emotional isolation, sexual longing, self-deprecating and dark humour, and anti-establishment stances.

Morrissey was born to working-classIrishimmigrants inDavyhulme,Lancashire,England; the family lived in Queen's Court near the Loreto convent inHulmeand his mother worked nearby at theHulme Hippodromebingo hall. They moved because of the 1960s demolitions of almost all the Victorian-era houses in Hulme, known as 'slum clearance', and he grew up in nearbyStretford.[5]As a child, he developed a love of literature,kitchen sink realism,and 1960s pop music. In the late 1970s, he fronted thepunk rockbandthe Nosebleedswith little success before beginning a career in music journalism and writing several books on music and film in the early 1980s. He formed the Smiths withJohnny Marrin 1982 and the band soon attracted national recognition fortheir eponymous debut album.As the band's frontman, Morrissey attracted attention for his trademarkquiffand witty and sardonic lyrics. Deliberately avoiding rock machismo, he cultivated the image of a sexually ambiguous social outsider who embraced celibacy. The Smiths released three further studio albums—Meat Is Murder,The Queen Is Dead,andStrangeways, Here We Come—and had a string of hit singles. The band were critically acclaimed and attracted a cult following. Personal differences between Morrissey and Marr resulted in the separation of the Smiths in 1987.

In 1988, Morrissey launched his solo career withViva Hate.This album and its follow-ups—Kill Uncle(1991),Your Arsenal(1992), andVauxhall and I(1994)—all did well on the UK Albums Chart and spawned multiple hit singles. He took onAlain WhyteandBoz Booreras his main co-writers to replace Marr. During this time his image began to shift into that of a burlier figure who toyed with patriotic imagery and working-class masculinity. In the mid-to-late 1990s, his albumsSouthpaw Grammar(1995) andMaladjusted(1997) also charted but were less well received. Relocating to Los Angeles, he took a musical hiatus from 1998 to 2003 before releasing a successful comeback album,You Are the Quarry,in 2004. Ensuing years saw the release of albumsRingleader of the Tormentors(2006),Years of Refusal(2009),World Peace Is None of Your Business(2014),Low in High School(2017),California Son(2019), andI Am Not a Dog on a Chain(2020), as well ashis autobiographyand his debut novel,List of the Lost(2015).

Highly influential, Morrissey has been credited as a seminal figure in the emergence ofindie pop,indie rock,andBritpop.In a 2006 poll for theBBC'sCulture Show,Morrissey was voted the second-greatest living British cultural icon.[6]His work has been the subject of academic study.[7][8]He has been a controversial figure throughout his music career due to his forthright opinions and outspoken nature, endorsing vegetarianism andanimal rightsandcriticising royaltyand prominent politicians. He has also supported far-right activism with regard to British heritage, and defended a particular vision ofnational identitywhile critiquing the effects of immigration on the UK.[9]

Early life[edit]

Childhood: 1959–1976[edit]

I lost myself in music at a very early age, and I remained there... I did fall in love with the voices I heard, whether they were male or female. I loved those people. I really, really did love those people. For what it was worth, I gave them my life... my youth. Beyond the perimeter of pop music there was a drop at the end of the world.

— Morrissey, 1991.[10]

Steven Patrick Morrissey was born on 22 May 1959[11]atPark HospitalinDavyhulme,Lancashire.[12]His parents, Elizabeth (néeDwyer) and Peter Morrissey,[12]wereIrish Catholics[13]who had emigrated toManchesterfromDublinwith his only sibling, elder sister Jacqueline, a year before his birth.[12]Morrissey claims he was named after American actorSteve Cochran,[14]although he may instead have been named in honour of his father's brother who died in infancy, Patrick Steven Morrissey.[15]His earliest home was acouncil houseat 17 Harper Street in the Queen's Square area ofHulme,inner Manchester, since demolished.[16][17][5]Living in that area as a child, he was deeply affected by theMoors murders,in which a number of local children were killed; the crimes had a lasting impression on him and would inspire the lyrics of the Smiths song "Suffer Little Children".[18]He also became aware of theanti-Irish sentimentin British society againstIrish immigrants to Britain.[19]In 1970, after the 'slum clearances' of Victorian-era houses in Hulme, the family moved to another council house at 384 King's Road inStretford.[20]

Following a primary education at St Wilfred's Primary School,[20]Morrissey failed his11-plusexam[21]and proceeded to St Mary's Secondary Modern School, an experience he found unpleasant.[22]He excelled at athletics,[23]though he was an unpopularlonerat the school.[24]He has been critical of his formal education, later stating, "The education I received was so basically evil and brutal. All I learnt was to have no self-esteem and to feel ashamed without knowing why."[23]He left school in 1975, having received no formal qualifications.[25]He continued his education atStretford Technical College,[25]where he gained threeO-Levelsin English literature, sociology, and the General Paper.[26]In 1975, he travelled to the U.S. to visit an aunt who lived inStaten Island.[5]The relationship between his parents was strained, and they ultimately separated in December 1976, with his father moving out of the family home.[27]

Morrissey's librarian mother encouraged her son's interest in reading.[28]He took an interest in feminist literature,[29]and particularly liked the Irish authorOscar Wilde,whom he came to idolise.[30]The young Morrissey was a fan of the television soap operaCoronation Street,which focused on working-class communities in Manchester; he sent proposed scripts and storylines to the show's production company,Granada Television,although all were rejected.[31]He was also a fan ofShelagh Delaney'sA Taste of Honeyand its1961 film adaptation,which was a drama focusing on working-class life inSalford.[32]Many of his later songs directly quotedA Taste of Honey.[33]

Of his youth, Morrissey has said, "Pop music was all I ever had, and it was completely entwined with the image of the pop star. I remember feeling the person singing was actually with me and understood me and my predicament."[34]He later revealed that the first record he purchased wasMarianne Faithfull's 1965 single "Come and Stay With Me".[35]He became aglam rockfan in the 1970s,[36]enjoying the work of English artists likeT. Rex,David BowieandRoxy Music.[37]He was also a fan of American glam rock artists such asSparks,Jobriathand theNew York Dolls.[38]He formed a British fan club for the latter, attracting members through small adverts in the back pages of music magazines.[39]It was through the New York Dolls' interest in female pop singers from the 1960s that Morrissey too developed a fascination for such artists,[40]includingSandie Shaw,Twinkle,andDusty Springfield.[41]

Early bands and published books: 1977–1981[edit]

Having left formal education, Morrissey proceeded through a series of jobs, as a clerk for the civil service and then theInland Revenue,[42]as a salesperson in arecord store,and as a hospital porter, before abandoning employment and claimingunemployment benefits.[43]He used much of the money from these jobs to purchase tickets for gigs, attending performances byTalking Heads,theRamones,andBlondie.[44]He regularly attended concerts, having a particular interest in the alternative and post-punk music scene.[45]Having met the guitaristBilly Duffyin November 1977, Morrissey agreed to become the vocalist for Duffy's punk bandthe Nosebleeds.[46]Morrissey co-wrote a number of songs with the band[47]— "Peppermint Heaven", "I Get Nervous" and "I Think I'm Ready for the Electric Chair"[46]—and performed with them in support slots forJilted Johnand thenMagazine.[40]The band soon disbanded.[48]

After the Nosebleeds' break-up, Morrissey followed Duffy to joinSlaughter & the Dogs,briefly replacing original singer Wayne Barrett. He recorded four songs with the band and they auditioned for a record deal in London. After the audition fell through, Slaughter & the Dogs became Studio Sweethearts, without Morrissey.[49]He came to be known as a minor figure within Manchester's punk community.[50]By 1981, he had become a close friend ofLinder Sterling,the frontwoman of punk-jazz ensembleLudus;her lyrics and style of singing both influenced him.[51]Through Sterling, he came to knowHoward DevotoandRichard Boon.[50]At the time, Morrissey's best male friend was James Maker; he would visit Maker in London or they would meet in Manchester, where they visited the city's gay bars and gay clubs, in one case having to escape from a gang ofgay bashers.[52]

Wanting to become a professional writer,[53]Morrissey considered a career in music journalism. He frequently wrote letters to the music press and was eventually hired by the weekly music review publicationRecord Mirror.[45]He wrote several short books for local publishing company Babylon Books: in 1981 it released a 24-page booklet he had written on the New York Dolls, which sold 3000 copies.[54]This was followed byJames Dean is Not Dead,about the late American film starJames Dean.[45]Morrissey had developed a love of Dean and had covered his bedroom with pictures of the dead film star.[55]

The Smiths[edit]

Establishing the Smiths: 1982–1984[edit]

In August 1978, Morrissey was briefly introduced to the 14-year-oldJohnny Marrby mutual acquaintances at aPatti Smithgig held at Manchester'sApollo Theatre.[47]Several years later, in May 1982, Marr turned up on the doorstep of Morrissey's house, there to ask Morrissey if he was interested in co-founding a band.[56]Marr had been impressed that Morrissey had authored a book on the New York Dolls,[57]and was inspired to turn up on his doorstep following the example ofJerry Leiber,who had formed his working partnership withMike Stollerafter turning up at the latter's door.[58]According to Morrissey: "We got on absolutely famously. We were very similar in drive."[59]The next day, Morrissey phoned Marr to confirm that he would be interested in forming a band with him.[60]Steve Pomfret—who had served as the band's first bassist—soon abandoned the band, to be replaced by Dale Hibbert.[61]Around the time of the band's formation, Morrissey decided that he would be publicly known only by his surname,[62]with Marr referring to him as "Mozzer" or "Moz".[63]In 1983, he forbade those around him from using the name "Steven", which he despised.[63]Morrissey was also responsible for choosing the band name of "the Smiths",[64]later informing an interviewer that "it was the most ordinary name and I thought it was time that the ordinary folk of the world showed their faces".[65]

Alongside developing their own songs, they also developed a cover ofthe Cookies' "I Want a Boy for My Birthday", the latter reflecting their deliberate desire to transgress established norms of gender and sexuality in rock in a manner inspired by the New York Dolls.[66]In August 1982, they recorded their first demo at Manchester's Decibel Studios,[67]and Morrissey took the demo recording toFactory Records,but they weren't interested.[68] In late summer 1982,Mike Joycewas adopted as the band's drummer after a successful audition.[69]In October 1982, they then gave their first public performance, as a support act forBlue Rondo à la Turkat Manchester'sThe Ritz.[70]Hibbert however was unhappy with what he perceived as the band's gay aesthetic; in turn, Morrissey and Marr were unhappy with his bass playing, and so he was removed from the band and replaced by Marr's old school friendAndy Rourke.[71]

After the record companyEMIturned them down,[72]Morrissey and Marr visited London to hand a cassette of their recordings toGeoff Travisof theindependent record labelRough Trade Records.[73]Although not signing them to a contract straight away, he agreed to cut their song "Hand in Glove"as a single.[74]Morrissey chose ahomoeroticcover design in the form of aJim Frenchphotograph.[75] It was released in May 1983. The band soon generated controversy whenGarry Bushellof tabloid newspaperThe Sunalleged that their B-side "Handsome Devil" was an endorsement ofpaedophilia.[76]The band denied this, with Morrissey stating that the song "has nothing to do with children, and certainly nothing to do with child molesting".[77]In the wake of their single, the band performed their first significant London gig, gained radio airplay with aJohn Peelsession, and obtained their first interviews in music magazinesNMEandSounds.[78]

The follow-up singles "This Charming Man"and"What Difference Does It Make?"fared better when they reached numbers 25 and 12 respectively on theUK Singles Chart.[79]Aided by praise from the music press and a series of studio sessions for Peel andDavid JensenatBBC Radio 1,the Smiths began to acquire a dedicated fan base. In February 1984 they released their debut album,The Smiths,which reached number 2 on theUK Albums Chart.[79]

As frontman of the Smiths, Morrissey—described as "lanky, soft-spoken, bequiffed and bespectacled"[80]—subverted many of the norms that were associated with pop and rock music.[81]The band's aesthetic simplicity was a reaction to the excess personified by theNew Romantics,[82]and while Morrissey adopted an androgynous appearance like the New Romantics or earlier glam rockers, his was far more subtle and understated.[83]According to one commentator, "he was bookish; he woreNHSspectacles and a hearing aid on stage; he was celibate. Worst of all, he was sincere ", with his music being" so intoxicatingly melancholic, so dangerously thoughtful, so seductively funny that it lured its listeners... into a relationship with him and his music instead of the world. "[84]In anacademic paperon the band, Julian Stringer characterised the Smiths as "one of Britain's most overtly political groups",[85]while in his study of their work, Andrew Warns termed them "this most anti-capitalist of bands".[86]Morrissey had been particularly vocal in his criticism of then-Prime MinisterMargaret Thatcher;after the October 1984Brighton hotel bombing,he commented that "the only sorrow" of it was "that Thatcher escaped unscathed".[87]In 1988, he stated thatSection 28"embodies Thatcher's very nature and her quite natural hatred".[87]

The Smiths' growing success: 1984–1987[edit]

The Smiths brought realism to their romance, and tempered their angst with the lightest of touches. The times were personified in their frontman: rejecting all taints of rock n' roll machismo, he played up the social awkwardness of the misfit and the outsider, his gently haunting vocals whooping suddenly upward into a falsetto, clothed in outsize women's shirts, sporting National Health specs or a huge Johnny Ray-style hearing aid. This charming young man was, in the vernacular of the time, the very antithesis of a "rockist" —always knowingly closer to the gentle ironicistAlan Bennett,or self-lacerating diaristKenneth Williams,than a licentiousMick Jaggeror drugged-outJim Morrison.

— Paul A. Woods, 2007.[88]

In 1984, the band released two non-album singles: "Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now"(their first UK top-ten hit) and"William, It Was Really Nothing".The year ended with the compilation albumHatful of Hollow.This collected singles,B-sidesand the versions of songs that had been recorded throughout the previous year for the Peel and Jensen shows. Early in 1985, the band released their second album,Meat Is Murder,which was their only studio album to top the UK charts. The single-only release "Shakespeare's Sister"reached number 26 on the UK Singles Chart, though the only single taken from the album,"That Joke Isn't Funny Anymore",was less successful, barely making the top 50.[79]"How Soon Is Now?"was originally a B-side of" William, It Was Really Nothing ", and was subsequently featured onHatful of Hollowand the American, Canadian, Australian and Warner UK editions ofMeat Is Murder.Belatedly released as a single in the UK in 1985, "How Soon Is Now?"reached number 24 on the UK Singles Chart.

During 1985, the band undertook lengthy tours of the UK and the US while recording the next studio record,The Queen Is Dead.The album was released in June 1986, shortly after the single "Bigmouth Strikes Again".The record reached number 2 in the UK charts.[79]All was not well within the band. A legal dispute with Rough Trade had delayed the album by almost seven months (it had been completed in November 1985), and Marr was beginning to feel the stress of the band's exhausting touring and recording schedule.[89]Meanwhile, Rourke was fired in early 1986 for his use of heroin.[90]Rourke was temporarily replaced on bass guitar byCraig Gannon,but he was reinstated after only a fortnight. Gannon stayed in the band, switching to rhythm guitar. This five-piece recorded the singles "Panic"and"Ask"(withKirsty MacCollon backing vocals) which reached numbers 11 and 14 respectively on the UK Singles Chart,[79]and toured the UK. After the tour ended in October 1986, Gannon left the band. The band had become frustrated with Rough Trade and sought a record deal with a major label, ultimately signing withEMI,which drew criticism from some of the band's fanbase.[89]

In early 1987, the single "Shoplifters of the World Unite"was released and reached number 12 on the UK Singles Chart.[79]It was followed by a second compilation album,The World Won't Listen,which reached number 2 in the charts[79]—and the single "Sheila Take a Bow",the band's second (and last during the band's lifetime) UK top-10 hit.[79]Despite their continued success, personal differences within the band—including the increasingly strained relationship between Morrissey and Marr—saw them on the verge of breaking up. In July 1987, Marr left the band and auditions to find a replacement proved fruitless.

By the time that the band's fourth albumStrangeways, Here We Comewas released in September, the band had broken up. Morrissey attributed the band's break-up to the lack of a managerial figure—in a 1989 interview with then-teenage fanTim Samuels.[91]Strangewayspeaked at number 2 in the UK, but was only a minor US hit,[79][92]though it was more successful there than the band's previous albums.

Solo career[edit]

Early solo work: 1988–1991[edit]

Several months before the Smiths dissolved, Morrissey enlistedStephen Streetas his personal producer and new songwriting partner, with whom he could begin his solo career.[93]By September 1987, he had begun work on his first solo album,Viva Hate,at Wool Hall Studios nearBath;[93]it was recorded with the musiciansVini ReillyandAndrew Paresi.[94]Rather than featuring pre-existing images of celebrities, as the Smiths' album and single covers had done, the cover sleeve ofViva Hatefeatured a photograph of Morrissey taken byAnton Corbijn.[95]In February 1988, EMI released the first single from this album, "Suedehead",which reached number 5 on the British singles chart, a higher position than any Smiths single had achieved.[96]The second single from the album, "Everyday Is Like Sunday",was released in June and reached number 9.[97]The album reached number 1 on the UK album charts.[95]The album's final song, "Margaret on the Guillotine", featured descriptions of Thatcher being executed; in response, the Conservative Member of ParliamentGeoffrey Dickensaccused Morrissey of being involved in a terrorist network and policeSpecial Branchconducted a search of his Manchester home.[98]

Morrissey's first solo performance took place atWolverhampton's Civic Hall in December 1988.[99]The event attracted huge crowds, withNMEjournalist James Brown observing that "the excitement and atmosphere inside the hall was like nothing I have ever experienced at any public event".[100]FollowingViva Hate,Morrissey put out two new singles; "The Last of the Famous International Playboys"was about theKray twins,gangsters who operated in London's East End, and reached number 6 on the UK singles chart.[101]This was followed by "Interesting Drug",which reached number 9.[102]After his songwriting partnership with Street ended and was replaced byAlan WinstanleyandClive Langer,[103]he recorded "Ouija Board, Ouija Board",released as a single in November 1989; it reached number 18.[103]Christian spokespeople and tabloid newspapers condemned the song, claiming that it promotedoccultism,to which Morrissey responded that "the only contact I ever made with the dead was when I spoke to a journalist fromThe Sun."[104]

With Winstanley and Langer he began work on his first compilation album,Bona Drag,although only recorded six new songs for it, the rest of the album comprising his recent singles and B-sides.[105]The album reached number 9 on the UK album chart.[106]Two of the newly recordedBona Dragtracks were released as singles: "November Spawned a Monster",a song about a woman who is a wheelchair user, reached number 12 in the charts but received criticism from some who believed that it mocked disabled people.[107]The second, "Piccadilly Palare",referenced Londonrent boysand featured terms from thepolarigay slang. Released in November 1990, it reached number 19 in the charts.[108]The song attracted some criticism from the British gay press, who were of the opinion that it was wrong for Morrissey to use polari when he was not openly gay;[109]in an interview the previous year he had nevertheless acknowledged his attraction to both men and women.[110]

AdoptingMark E. Nevinas his new songwriting partner,[111]Morrissey created his second solo album,Kill Uncle;released in March 1991, it peaked at number 8 on the album chart.[111]The two singles released in promotion of the album, "Our Frank"and"Sing Your Life",failed to break the Top 20 on the singles charts, reaching number 26 and 33 respectively.[111][112]Another of the album's tracks, "Found, Found, Found", alluded to Morrissey's friendship withMichael Stipe,the lead singer of American indie rock bandREM.[113] Planning his first solo tour, Morrissey assembled several musicians with a background inrockabillyfor his new backing group, including the guitaristBoz Boorer,Alain Whyteand Spencer Cobrin.[114]Morrissey began theKill Uncletour in Europe; he broughtPhrancas hissupport actand decorated the stage of each performance with a large image ofEdith Sitwell.[115]On the US leg of his tour, he sold out Los Angeles' 18,000 seatThe Forumin fifteen minutes, faster thanMichael JacksonorMadonnahad done.[116]During the performance,David Bowiejoined him onstage for a rendition of T. Rex's "Cosmic Dancer".[116]In the US, he sold out 25 of his 26 other performances;[116]one Texan appearance was filmed byTim Broadfor release as theVHSLive in Dallas.[117]He proceeded to Japan—where he was frustrated by the authorities' tough stance toward fans—and then Australasia, where he cancelled several dates due to acute sinusitis.[118]

The early 1990s were described by biographer David Bret as the "black phase" in Morrissey's relationship with the British music press, which was increasingly hostile and critical of him.[119]In some cases, this involved the press spreading misinformation, such as the claim that he and Phranc were recording a cover of "Don't Go Breaking My Heart";[120]others, such as those of Barbara Ellen inNME,were closer to personal attack than musical review.[121]NMEclaimed that his cancelled performances reflected a disrespect towards his fans.[122]He became increasingly reticent in talking to British music journalists,[123]expressing frustration at how they constantly compared his solo work with that of the Smiths; "my past is almost denying me a future".[124]He told one interviewer that the band he was then working with were technically better musicians than the Smiths had ever been.[124]

Changing image: 1992–1995[edit]

In July 1992, Morrissey released the albumYour Arsenal,which peaked at number 2 in the album chart.[125]It was the final release from producerMick Ronson;Morrissey related that working with Ronson had been "the greatest privilege of my life".[126]Your Arsenalreflected Morrissey's lament for what he regarded as the decline of British culture in the face of increasing Americanisation.[127]He told one interviewer that "everything is informed by American culture—everyone under fifty speaks American—and that's sad. We once had a strong identity and now that's gone completely".[127]A number of the tracks on the album, most notably "Certain People I Know"and" The National Front Disco ", dealt with the lives and experiences of tough, working-class youths.[128]Your Arsenalwas critically well received,[129]and often described as his best album sinceViva Hate.[125]The first single, "We Hate It When Our Friends Become Successful",had been released in April 1992 and peaked at number 17;[130]this was followed by "You're the One for Me, Fatty",which reached number 19 and" Certain People I Know ", which reached number 34.[131]From September to December, Morrissey embarked on a 53-dateYour Arsenaltour in which he varyingly decorated the stage with backdrops ofskinheadgirls,[132]Diana Dors,Elvis Presley,andCharlie Richardson.[133]One of the performances was recorded and released asBeethoven Was Deaf.[134]

By the release ofYour Arsenal,Morrissey's image had changed; according to Simpson, the singer had converted "from the aesthete interested in rough lads into a rough lad interested in aestheticism (and rough lads)".[135]According to Woods, Morrissey developed an air of "quietly assured masculinity", representing "a more robust, burlier, beefier version of himself",[136]while the poet and Morrissey fanSimon Armitagedescribed the transition as being one from that of "stick-thin, knock-me-over-with-a-feather campness" to that of a "mobster and bare-knuckle boxer image".[137]This new image was reflected in the cover art forYour Arsenal;a photograph taken by Sterling, it featured Morrissey onstage with his shirt open, displaying a muscular torso beneath.[135]

In mid-1993, Morrissey co-wrote his fifth album,Vauxhall and I,with Whyte and Boorer; it was produced bySteve Lillywhite.[138]Morrissey described the album as "the best I've ever made",[139]and at the time believed it would be either his final or penultimate work.[140]It was both a critical and commercial success,[141]topping the UK album chart in March 1994.[142]The album had been named forVauxhall,a district of South West London famous for theRoyal Vauxhall Taverngay pub.[139]One of the album's songs, "The More You Ignore Me, the Closer I Get",was released as a single at the time and reached number 8 in the UK.[139]The single's sleeve featured images of Jake Walters, a skinhead in his twenties, who was living with Morrissey at the time.[143]Walters had introduced Morrissey toYork Hall,a boxing venue inBethnal Green,part of London'sEast End,with the singer spending an increasing amount of time there.[144]

That year, he also released a non-album single, "Interlude",a duet withSiouxsie Sioux:the track was a cover of aTimi Yurosong. The record was published under the banner "Morrissey & Siouxsie"; due to record company issues, "Interlude" was only available on import outside Europe.[145]

In the autumn of 1994, Morrissey recorded five songs at South London'sOlympic Studios.[146]In January 1995 the single "Boxers"was released, reaching number 23 on the singles chart.[147]In February 1995, he embarked on theBoxerstour, supported by the bandMarionand featuring a backdrop depiction of the boxerCornelius Carr.[148]One of these performances was filmed byJames O'Brienand released as the VHSIntroducing Morrissey.[149]In December 1995, the song "Sunny"was released as a single; a lament for Morrissey's terminated relationship with Walters, the song was the first of Morrissey's singles not to chart.[146]In 1995 the compilation albumWorld of Morrisseywas released, containing largely B-sides.[150]

Move to Los Angeles: 1995–2003[edit]

After his contract with EMI expired, Morrissey signed toRCA.[151]On this label he recorded his next album,Southpaw Grammar,at theMiraval Studiosin southern France before releasing it in August 1995.[152]Its cover art featured an image of the boxerKenny Lane.[153]It reached number 4 in the UK album charts,[153]but made little impact compared to its two predecessors.[154] In September 1995, Morrissey served as the support act for the British leg of Bowie'sOutside Tour.[155]Backstage at theAberdeengig, Morrissey was taken ill and taken to hospital; he did not return for the rest of the tour.[156]Later referring to the tour critically, he said that when you become involved with Bowie, "you have to worship at the Temple of David".[157]

In December 1996, a legal case against Morrissey and Marr brought by Smiths' drummer Mike Joyce arrived at theHigh Court.Joyce alleged that he had not received his fair share of recording and performance royalties from his time with the band, calling for at least £1 million in damages and 25% of all future Smiths album sales. After a seven-day hearing, the judge ruled in favour of Joyce.[158][159]In summing up the case, Judge Justice Weeks referred to Morrissey as "devious, truculent and unreliable when his own interests were at stake", with the words "devious" and "truculent" being widely used in press coverage of the ruling.[160]Marr paid the money legally owed to Joyce but Morrissey launched an appeal against the ruling.[161]He said that the judge had been biased against him from the start of the proceedings because of his public criticisms of Thatcher and her government.[162]Morrissey lost his appeal in July 1998, although he launched another soon after;[162]this too was unsuccessful.[163]In a November 2005 statement, Morrissey said that Joyce had cost him £600,000 in legal fees alone and approximately £1,515,000 in total.[164]

Morrissey returned onIsland Recordsin 1997, releasing the single "Alma Matters"in July,[citation needed]followed by his next albumMaladjustedin August.[165] The album peaked at number 8 in the UK album charts. Its further two singles, "Roy's Keen"and"Satan Rejected My Soul",both peaked outside the top 30 on the UK singles chart.[112]Having been unhappy with the cover design forSouthpaw Grammar,Morrissey left control of cover art ofMaladjustedto his record company, but again was unsatisfied with the result.[166]

Uncutreported in 1998 that Morrissey no longer had a record deal.[167]The following year, he embarked on theOye Esteban Tour,and was one of the headliners of theCoachella Festivalin California.[168]

The England that I have loved, and I have sung about, and whose death I have sung about, I felt had finally slipped away. And so I was no longer saying, "England is dying." I was beginning to say, "Well, yes, it has died and here's the carcass" —so why hang around?

— Morrissey, on his move to Los Angeles.[169]

Leaving Britain, Morrissey purchased a house inLincoln Heights, Los Angeles.It had formerly been the residence ofCarole Lombardand had been re-designed byWilliam Haines.[170]Over the next few years he rarely returned to Britain.[170] In 2002, Morrissey returned with a world tour, culminating in two sold-out nights at theRoyal Albert Hall,during which he played as-yet unreleased songs.[171]Outside the US and Europe, concerts also took place in Australia and Japan.[172]During this time,Channel 4filmedThe Importance of Being Morrissey,a documentary which aired in 2003; it was Morrissey's first major screen interview to appear on British television.[173][174]He told interviewers that he was working on an autobiography,[175]and expressed criticism of reality television music shows likePop Idolwhich were then in their infancy.[176]

Comeback: 2004–2009[edit]

In 2003, Morrissey signed toSanctuary Records,where he was given the defunctreggaelabelAttack Recordsto use for his next project.[177][178]Produced byJerry Finnand recorded in both Los Angeles andBerkshire,Morrissey's seventh solo album wasYou Are the Quarry;it was released in May 2004.[179]The album's cover art featured an image of Morrissey carrying aTommy gun.[180]It peaked at number 2 on the UK album chart and number 11 on the U.S. Billboard album chart.[112]The first single, "Irish Blood, English Heart",reached number 3 in the UK singles chart, the highest ranked single of his career.[181]Promoting the album, he made appearances on bothTop of the PopsandLater with Jools Holland,[182]and gave his first television interview in 17 years onFriday Night with Jonathan Ross;Morrissey was visibly uncomfortable withJonathan Ross' questions.[183]He also agreed to interviews with various press outlets, including theNME,stating that "the nasty old guard" who controlled the magazine in the 1990s were gone and that it was not "the smellyNMEany more ".[184]

To promote the album, Morrissey embarked on a world tour from April to November.[185]He marked his 45th birthday with a concert at theManchester Arena,supported byFranz Ferdinand;[186]it was recorded for release as the DVDWho Put the M in Manchester?.[citation needed] Morrissey was also invited to curate that year'sMeltdownfestival at London'sSouthbank Centre.Among the acts he secured wereSparks,Loudon Wainwright III,Ennio Marchetto,Nancy Sinatra,The Cockney Rejects,Lypsinka,The Ordinary Boys,The Libertines,and playwrightAlan Bennett.[187]He had unsuccessfully attempted to secure appearances fromBrigitte BardotandMaya Angelou.[188]That year he also performed at several UK music festivals, includingLeeds,Reading,andGlastonbury.[189]

Morrissey's eighth studio album,Ringleader of the Tormentors,was recorded in Rome and released in April 2006. It debuted at number 1 in the UK album charts and number 27 in the US.[190][191]The album yielded four singles: "You Have Killed Me","The Youngest Was the Most Loved","In the Future When All's Well",and"I Just Want to See the Boy Happy".[citation needed]The album was produced byTony Visconti;Morrissey called the album "the most beautiful—perhaps the most gentle—so far".Billboarddescribed the album as showcasing "a thicker, more rock-driven sound".[192]

In December 2007, Morrissey signed a new deal withDecca Records,which included aGreatest Hitsalbum and a new studio album.[193]Greatest Hitscharted at number 5 in the UK album chart.[190]"That's How People Grow Up"was the first single fromGreatest Hits,reaching number 14 in the UK charts.[190]A second single from the album, "All You Need Is Me",followed.

His ninth studio album,Years of Refusal,originally due in September, was postponed until February 2009, as a result of the death of producerJerry Finn,[194]and the lack of an American label to distribute the album.[195]When released by the Universal Music Group, it reached number 3 in the UK Albums Chart[196]and 11 in the USBillboard200.[197]The record was widely acclaimed by critics,[198]with comparisons made toYour Arsenal[199]andVauxhall and I.[200]A review fromPitchfork Medianoted that withYears of Refusal,Morrissey "has rediscovered himself, finding new potency in his familiar arsenal. Morrissey's rejuvenation is most obvious in the renewed strength of his vocals" and called it his "most venomous, score-settling album, and in a perverse way that makes it his most engaging".[200]"I'm Throwing My Arms Around Paris"and"Something Is Squeezing My Skull"were released as the record's singles. The song" Black Cloud "features the guitar playing ofJeff Beck.Throughout 2009, Morrissey toured to promote the album. As part of the extensive Tour of Refusal, Morrissey followed a lengthy US tour with concerts booked in Ireland, the UK, and Russia.[201]

In October 2009,Swords,a B-sides collection of material released between 2004 and 2009, was released.[202]It peaked at 55 on the UK albums chart, and Morrissey later called it "a meek disaster".[203]On the second date of the UK tour to promoteSwords,Morrissey collapsed onstage inSwindon,[204]and was briefly hospitalised.[205]Following theSwordstour, Morrissey had fulfilled his contractual obligation to Universal Records and was without a record company.[206]

Further albums and literary work: 2010–2019[edit]

In April 2011, EMI issued a new compilation,Very Best of Morrissey,for which the singer had chosen the track list and artwork.[207]In March 2011, Morrissey took Ron Laffitte as his manager.[208]In June and July 2011, Morrissey played a UK tour;[209]during his 2011 performance atGlastonbury Festival,Morrissey criticised UK Prime MinisterDavid Cameronfor attempting to prevent a ban on wild animals performing in circuses, calling him a "silly twit".[210]This was followed by several dates elsewhere in Europe.[211]Morrissey's 2012 tour started in South America and continued through Asia and North America. Morrissey played concerts in Belgium, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Israel, Portugal, England, and Scotland. In late September, while visiting Strand Bookstore in Manhattan, he saved an elderly lady who had fainted beside him.[212]Between January and March 2013, Morrissey toured 32 North American cities, beginning in Greenvale, New York and ending in Portland, Oregon.[213]Patti Smithand her band were special guests at theStaples Centerconcert in Los Angeles, and Kristeen Young opened on all nights.[214]

In January 2013, Morrissey was diagnosed with a bleeding ulcer and several engagements were rescheduled.[215]On 7 March, Morrissey was hospitalised again, this time with pneumonia in both lungs.[216]One week later, the rest of the tour was cancelled.[217]During his rehabilitation he spent time in Ireland, where he watchedthe country's football teamplay a match againstAustriain the company of his cousinRobbie Keane.[218][219]

In April, EMI reissued the single "The Last of the Famous International Playboys", backed by three new songs: "People Are the Same Everywhere", "Action Is My Middle Name", and "The Kid's a Looker", all recorded live in 2011.[220]Starting in June, Morrissey performed in Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Peru and Chile.[221]In August, Morrissey's concert at Hollywood High School on 2 March 2013, had a worldwide cinema release.[clarification needed]Morrissey: 25 Livemarks Morrissey's 25th year as a solo artist, and was the first authorised live Morrissey DVD in nine years.[222]In July, Morrissey cancelled the South American leg of his tour due to a "lack of funding", saying it was "the last of many final straws".[223]

In October 2013, Morrissey's autobiography, titledAutobiography,was released after a "content dispute" had delayed it from the initial release date of 16 September 2013.[224]The book's release caused controversy as it was published as a "contemporary classic" under thePenguin Classicslabel at Morrissey's request, which some critics felt devalued the Penguin Classics label.[225][226]Morrissey had completed the 660-page book in 2011,[227]before shopping it to publishers such asPenguin Books[228]andFaber and Faber.[229]The book received divergent reviews:The Daily Telegraphgiving it a five-star review that described it as "the best written musical autobiography sinceBob Dylan'sChronicles",whileThe Independentcriticised the book's "droningnarcissism"as well as its status as a Penguin Classic.[230]The book entered the UK book charts at number 1, nearly 35,000 copies being sold in its first week.[231]In December, a 2011 live cover version ofLou Reed's "Satellite of Love",was released as a single.[232]

In January 2014, Morrissey signed a two-record deal withCapitol Music.[233]His tenth studio album,World Peace Is None of Your Business,was released in July.[234]Prior to its release, he embarked on a US tour in May,[235]but was hospitalised in Boston in early June, cancelling the remaining nine tour dates.[236]After finishing a six date tour in the UK, he did a US tour during June and July, including a concert in New York with special guestBlondieatMadison Square Garden.[237]In July 2015, he publicly claimed that an airport security guard had groped him atSan Francisco International Airport.He filed a sexual assault complaint; theTransportation Security Administrationfound no supporting evidence to act on the allegation.[238]In August, Capitol Music and Harvest Records ended their contracts with Morrissey.[239]In October, he disclosed he had received treatment forBarrett's oesophageal cancer.[240][238]

In September 2015,Penguin Bookspublished Morrissey's first novel,List of the Lost.[241][242]

In November 2017, his eleventh studio album,Low in High School,was released throughBMGand Morrissey's own Etienne record label.[243]That same month, Morrissey attracted press attention and criticism for comments made in an interview withDer Spiegel:he stated that it was "quite sad" that distinct national identities in Europe were being undermined by politicians trying "to introduce a multicultural aspect to everything",[244][245][246]and that some individuals claiming victimhood as part of theMe Too movementwere not genuine victims of sexual assault but were "simply disappointed".[244][247]Morrissey accusedDer Spiegelof misquoting him and said it would be his last print interview.[248][249]He played two shows at Los Angeles'Hollywood Bowlin November.[250]Morrissey's first UK tour since 2015 began in Aberdeen and concluded in London.[251]

In November 2018, Morrissey released a cover ofthe Pretenders' "Back on the Chain Gang",[252]performing it onThe Late Late Show with James Corden.[253]In May 2019, Morrissey played a seven-night residency at theLunt-Fontanne TheatreonBroadway,[254]prior to the release of his twelfth studio album, acovers albumtitledCalifornia Son.

Two more albums, unreleased album andWithout Music The World Dies:2020–present[edit]

Morrissey released an 11-track albumI Am Not a Dog on a Chainin late March 2020. The lead single, "Bobby, Don't You Think They Know?" featuringMotownsoul singerThelma Houston,was also made available on streaming sites.[255]

In November 2020, Morrissey's deal with BMG expired and was not renewed.[256]Morrissey completed aLas Vegasresidency in July 2022 titled "Viva Moz Vegas" for the second year in a row.[257]He completed tour dates in the UK and Ireland.[258][259]

On 29 October 2022, it was announced that Morrissey would be releasing his fourteenth solo albumBonfire of Teenagersin February 2023 onCapitol Recordsin the US, although he did not sign with a label for a UK release.[260]The album has eleven songs produced byAndrew Wattand featuresRed Hot Chili PeppersmembersChad SmithandFleaalongside their former bandmateJosh Klinghoffer.Guests also included singersMiley CyrusandIggy Popwho contributed backing vocals.[261]In addition, Capitol planned to re-issue several of Morrissey's albums released between 1995 and 2014, with the exception ofMaladjusted.[262]On 15 November, it was announced thatBonfire of Teenagerswas no longer scheduled to release in February, with Morrissey saying that the fate of the album was exclusively in the hands of the label.[263]

On 25 November 2022, the album's lead single, "Rebels Without Applause", was released by Capitol Records worldwide.[264]On 23 and 24 December, Morrissey announced that he had voluntarily parted ways with his current management companies,Maverickand Quest, withdrew any association with Capitol Records, and revealed that Cyrus requested to have her vocals removed from the album, which still remains under the control of Capitol and would no longer be releasing it.[265][266][267][268]He later confirmed in February 2023 that Capitol, while still maintaining control of the album, will not releaseBonfire of Teenagers;he also suggested that the album had been "sabotaged" by Capitol.[269]

On 8 December 2022, Morrissey announced that in January and February 2023, he would record a new album, titledWithout Music the World Dies.[270]On 20 February 2023, he announced the album had been completed and unveiled its tracklist, before offering the album to any record labels orprivate investorswho would be willing to distribute it.[271]

In 2024, "Interlude", Morrissey's duet with Siouxsie, was re-released on 12-inch gold vinyl forRecord Store Dayon 20 April 2024; it was available in the UK and Europe only.[272]

Artistry[edit]

Lyrics[edit]

Mark Simpsoncharacterised Morrissey as "the anti-pop idol", representing "the last, greatest and most gravely worrying product of an era when pop music was all there was".[273]Music journalist and biographerJohnny Roganstated that Morrissey's œuvre seems based on "endlessly re-examining a lost, painful past".[274]Morrissey's lyrics have been described as "dramatic, bleak, funnyvignettesabout doomed relationships, lonely nightclubs, the burden of the past and the prison of the home ".[275]According to Mark Simpson, there is a common feeling that his music's emphasis on the sadness of life is depressing.[276]

His lyrics are characterised by their usage of black humour, self-deprecation, and the pop vernacular.[277] Many of his lyrics avoid mentioning the gender of the narrator, and thus provide both male and female listeners with multiple points of identification.[278]Simpson felt that his lyrics often highlighted "the essential absurdity of gender".[279]Discussing the Smiths' lyrics in 1992, Stringer highlighted that they placed great emphasis on the concept of Englishness, but added that unlike the contemporaryTwo-Toneandacid housemovements, they focused on white England rather than exploring its multi-cultural counterpart.[280]Although noting that during the 1980s emphasising white identity was a trait closely linked with right-wing politics, Stringer expressed the view that the Smiths represented "the only sustained response that white, English pop/rock music was able to make" against the Thatcher government's "appropriation of white, English national identity".[280]

His lyrics have expressed disdain for many elements of British society, including the government, church, education system, royal family, meat-eating, money, gender, discos, fame, and relationships.[281]In his lyrics for the Smiths, Morrissey avoided explicit descriptions of the consummation of sex; rather, he sings about the anticipation, frustration, aversion, or final disappointment with sex.[282]Stringer suggested that this deliberate avoidance of sex was a reflection of the band's 'Englishness' because it invoked English cultures' "lack of emotional expression, the way in which feelings, and especially sexual feelings, cannot be expressed directly through casual touch, body contact and so on".[283] Male homoerotic elements can be found in many of the Smiths' lyrics,[284]but these also included sexualised descriptions featuring women.[285]

Morrissey has described having "a macabre fascination" with violence.[286]Simpson opined that Morrissey's lyrics "bleed and throb with violent imagery", citing the references to bus crashes and suicide pacts in "There is a Light that Never Goes Out", smashed teeth in "Bigmouth Strikes Again", andnuclear apocalypsein both "Ask" and "Everyday is Like Sunday".[287]More broadly, Morrissey had a longstanding interest in thuggery, whether that be murderers, gangsters, rough trade, or skinheads.[153]

Performance style[edit]

Morrissey's vocals have been cited as having a particularly distinctive quality.[288]Simpson believed that Morrissey's work embodied and personified that of the "Northern Women", speaking in styles of vernacular language that would be common to many women living innorthern England.[289]In this he was strongly influenced by the Northern singerCilla Black,who had a successful career as a pop music singer in the 1960s,[290]as well asViv Nicholson,who similarly earned fame during that decade.[290]Other female singers from that decade who have been cited as an influence on Morrissey have been the ScottishLulu,[290]and the EssexerSandie Shaw.[291]However, Stringer noted that rather than expressly singing in a Mancunian working-class accent, Morrissey adopted a "very clipped, precise enunciation" and sang in "clear English diction".[292]He is also noted for his unusualbaritonevocal style (though he sometimes usesfalsetto).[293]

When performing onstage, he often whips his microphone cord about, particularly during his up-tempo tracks.[294]Simpson believed that Morrissey often gave "slyly aggressive gestures" while onstage; he cited two instances fromTop of the Pops,one in which Morrissey used hand gestures to pretend shooting at the audience during "Shoplifters of the World Unite" and another in which he turned his microphone cord into a hangman's noose while repeating the lyrics "Hang the DJ, hang the DJ" in the song "Panic".[295]Rogan claimed that Morrissey exhibited "a power onstage which I have seldom seen from any other artiste of his generation", and that while performing he "oozes charisma, offering that peculiar combination of gauche vulnerability and athleticism".[274]

On various occasions, Morrissey has expressed anger when he believes that bouncers and the security teams at his concerts have treated the audience poorly. For instance, at hisSan Antonioconcert as part of theYour Arsenaltour he stopped his performance to rebuke bouncers for hitting fans.[296]

On 12 November 2022, while playing a live show in Los Angeles at theGreek Theater,he finished the set just after 9 songs and left without notice, upsetting many fans.[297]The bandmates hung around for over 10 minutes before realizing he was not coming back and it was announced that the show was being cancelled for "unforseen circumstances." It was speculated by some fans that the weather may have been too cold for him.[298]

Personal life[edit]

Throughout his career, Morrissey has retained an intensely private personal life.[299]A longtime resident of Los Angeles in the US, he also has homes in Italy, Switzerland and the UK.[300]In 2017, Los Angeles declared 10 November "Morrissey Day".[301]Friends refer to him as "Morrissey",[302]and he dislikes the nickname "Moz", telling one interviewer that "it's like something you'd squirt on the kitchen floor".[302]His mother, Elizabeth Anne Dwyer, died in August 2020 at the age of 82 fromgallbladder cancer.[303]

Morrissey has described himself alapsed Catholic[304]and has criticised theCatholic Church.[305]In 1991, he said that he believed in anafterlife.[104]Morrissey is a cousin of Irish footballerRobbie Keaneand once said, "To watch [Keane] on the pitch—pacing like a lion, as weightless as an astronaut, is pure therapy."[306][307]He is also a fan of boxing.[308]Morrissey has described having clinical depression, for which he has pursued professional help.[309]

Public image[edit]

Julian Stringer has characterised Morrissey as a man with various contradictory traits, being "an ordinary, working-class 'anti-star' who nevertheless loves to hog the spotlight, a nice man who says the nastiest things about other people, a shy man who is also an outrageous narcissist".[85]He further suggested that part of Morrissey's appeal was that he conveyed the image of a "cultivated English gentleman, being every inch the typically English 'gent' he is perfectly representative of that type's loathing for cant and hypocrisy, and his fragile, quasi-gay sexuality".[310]Similarly, Morrissey biographerDavid Bretdescribed him as being "quintessentially English",[299]while Mark Simpson termed him aLittle Englander.[311]Morrissey is known for his criticism of the British music press, royalty, politicians and people who eat meat.[312]According to Bret, his "withering attacks" on those he disliked are typically delivered in a "laid-back" manner.[173]

During the 1980s, interviewerPaul Morleystated that Morrissey "sets out to be a decent man and he succeeds because that is what he is".[313]Eddie Sanderson, who interviewed Morrissey forThe Mail on Sundayin 1992, said that "underneath all the rock star flim-flam, Morrissey is actually a very nice chap, excellent company, perfectly willing and able to talk about any subject one cared to throw at him".[314]Having photographed him in 2004, Mischa Richter described Morrissey as "genuinely lovely".[315]

Animal rights advocacy[edit]

A vocal advocate ofanimal welfareandanimal rightsissues,[304]Morrissey has been a vegetarian since the age of 11.[316]He has explained his vegetarianism by saying that "if you love animals, obviously it doesn't make sense to hurt them".[317]Morrissey announced in 2015 that he is avegan.He spoke of difficulties transitioning from vegetarianism to veganism.[318]In a 2018 interview, Morrissey stated that he "refuse[s] to eat anything that had a mother" but has always had difficulties with food, stating that he only eats bread, potatoes, pasta and nuts despite the increasing availability of more varied vegan food.[319]

Morrissey is a supporter ofPeople for the Ethical Treatment of Animals(PETA). In recognition of his support, PETA honoured him with theLinda McCartneyMemorial Award at their 25th Anniversary Gala on 10 September 2005.[320]He appeared in a PETA advert in 2012, encouraging people to have their dogs and catsneuteredto help reduce the number of homeless pets.[321]In 2014, PETA worked with animator Anna Saunders to create a cartoon calledSomedayin honour of Morrissey's 55th birthday. It features his song "I Know It's Gonna Happen Someday" and highlights the journey of a young chick.[322]

In January 2006, Morrissey attracted criticism when he stated that he accepts the motives behind the militant tactics of theAnimal Rights Militia,saying, "I understand why fur-farmers and so-called laboratory scientists are repaid with violence—it is because they deal in violence themselves and it's the only language they understand."[323]He has criticised people who are involved in the promotion of eating meat, includingJamie Oliver[324]andClarissa Dickson Wright.[325]The latter had already been targeted by some animal rights activists for her stance onfox hunting.In response, Dickson Wright stated, "Morrissey is encouraging people to commit acts of violence and I am constantly aware that something might very well happen to me."[326]Conservative MPDavid Daviscriticised Morrissey's comments, saying that "any incitement to violence is obviously wrong in a civilised society and should be investigated by the police".[327]Morrissey has also criticised theBritish royal familyfor their involvement in fox hunting.[312]

In 2006, Morrissey refused to include Canada in his world tour that year and supported a boycott of Canadian goods in protest against the country's annualseal hunt,which he described as a "barbaric and cruel slaughter".[328]In 2018, he changed his approach, feeling that his previous "stance was ultimately of no use and helped no one", and pledged to donate to animal protection groups in the cities where he would perform. He also invited those groups to set up stalls at his concerts.[329]

During an interview withSimon Armitagein 2010, Morrissey said that "you can't help but feel that the Chinese are a subspecies" due to their "horrific"treatment of animals.[330]Armitage said: "He must have known it would make waves, he's not daft. But clearly, when it comes to animal rights and animal welfare, he's absolutely unshakable in his beliefs. In his view, if you treat an animal badly, you are less than human."[331]

At a concert inWarsawon 24 July 2011, Morrissey stated, "We all live in a murderous world, as the events in Norway have shown, with 97 [sic] dead. Though that is nothing compared to what happens inMcDonald'sandKentucky Fried Shitevery day. "[332]His comments, referencing the2011 Norway attacksthat resulted in the killing of 77 people, were described as crude and insensitive byNME.[333]He later elaborated on his statement, saying, "If you quite rightly feel horrified at the Norway killings, then it surely naturally follows that you feel horror at the murder of ANY innocent being. You cannot ignore animal suffering simply because animals 'are not us'. "[334]

In February 2013, after much speculation,[335]it was reported that theStaples Centerhad agreed for the first time to make every vendor in the arena completely vegetarian for Morrissey's performance on 1 March, contractually having all McDonald's vendors close down. In a press release, Morrissey stated, "I don't look upon it as a victory for me, but a victory for the animals." The request was previously denied toPaul McCartney.[336][337]Despite these reports, the Staples Center retained some meat vendors while closing down McDonald's.[338]Later in February, Morrissey cancelled an appearance onJimmy Kimmel Live!after learning that the guests for that night also included the cast ofDuck Dynasty,a reality show about a family who create duck calls for use in hunting. Morrissey referred to them as "animal serial killers".[339]

In 2014, Morrissey stated that he believed there is "no difference between eating animals and paedophilia. They are both rape, violence, murder."[340]In September 2015, he expressed his revulsion at the "Piggate"scandal, saying that if Prime MinisterDavid Cameronhad really inserted "a private part of his anatomy" into the mouth of a dead pig's severed head while at university, then it showed "a callousness and complete lack of empathy entirely unbefitting a man in his position, and he should resign".[341][342]Also in September, he called Australian politicianGreg Hunt's campaign to cull 2 million invasive cats "idiocy", describing the cats as smaller versions ofCecil the lion.[343]

Morrissey came under controversy in 2019 when he banned all meat products from a venue he was performing at inHouston.Musicians Josh A andJake Hillcalled out Morrissey and criticized the ban, cancelling their show in protest.[344][345]The duo eventually released adiss trackon him in October 2019, titledLowlife.[346]

Sexuality[edit]

Morrissey's sexuality has been the subject of much speculation and coverage in the British press during his career,[299]with claims varyingly being made that he was celibate, a frustrated heterosexual, or bisexual.[304]In a 1980 letter he described both himself and his "girlfriend" as bisexual, although adding that he "hate[d] sex".[347]TheEncyclopædia Britannicastates that he created a "compellingly conflicted persona (loudly proclaimed celibacy offset by coy hints of closeted homosexuality)" that has "made him a peculiar heartthrob".[348]Speculation was further fuelled by the frequent references to gay subculture and slang in his lyrics. In 2006 Liz Hoggard fromThe Independentsaid: "Only 15 years after homosexuality had beendecriminalised,his lyrics flirted with every kind of gay subculture. "[349]

During his years with the Smiths, Morrissey professed to being celibate, which stood out at a time when much of pop music was dominated by visible sexuality.[350]Marr said in a 1984 interview that Morrissey "doesn't participate in sex at the moment and hasn't done so for a while".[351]Repeatedly, interviewers asked Morrissey if he was gay, which he denied.[352]In response to one such inquiry in 1985, he stated that "I don't recognise such terms as heterosexuality, homosexuality, bisexuality, and I think it's important that there's someone in pop music who's like that. These words do great damage, they confuse people and they make people feel unhappy, so I want to do away with them."[352]As his career developed, there was increased pressure placed on him tocome out of the closet,[353]although he presented himself as a non-practising bisexual.[354]In a 1989 interview, he said that he was "always attracted to men and women who were never attracted to me" and thus he did not have "relationships at all".[110]In 2013, he released a statement that said, "Unfortunately, I am not homosexual. In technical fact, I am humasexual. I am attracted to humans. But, of course... not many."[355]

In 1997, Morrissey said that he had abandoned celibacy and that he had a relationship with a Cockney boxer.[356]That person was revealed in his autobiography to be Jake Walters. Their relationship began in 1994, and they lived together until 1996.[357]In a March 2013 interview, Walters said, "Morrissey and I have been friends for a long time, probably around 20 years."[358]Morrissey was later attached to Tina Dehghani. He discussed having a child with Dehghani, with whom he described having an "uncluttered commitment".[357][359]In his autobiography Morrissey also mentions a relationship with a younger Italian man, known only as "Gelato", with whom he sought to buy a house in around 2006.[360][361]

In a 2015 interview, Morrissey stated: "I don't fit into any sexual category at all so I don't feel people see it as being sexual, but as being intimate."[362]

Political opinions[edit]

British politics[edit]

In anacademic paperon the Smiths, Julian Stringer characterised the band as "one of Britain's most overtly political groups",[85]while Andrew Warns termed them the "mostanti-capitalistof bands ".[86]Simon Goddard described Morrissey as being "pro-working class, anti-elite and anti-institution. That includes all political parties, parliament itself, allpublic schools,Oxbridge, the Catholic church, the monarchy, the EU, the BBC, the broadsheet press and the music press. Because his comments are not consistent with any one political agenda it confuses people, especially onthe left.If anything, he's a professionalRefusenik."[363]

Morrissey has exhibited enduring anti-royalist views from his teenage years and has fiercely criticised theBritish monarchy.[364]In a 1985 interview withSimon Garfield,he stated that he had always "despised royalty" and that royalist sentiment is a "false devotion".[365]In a 2011 interview, he publicly identified as arepublican,stating that he regarded theBritish royal familyas "benefit scroungers and nothing else".[366]In a 2012 interview withStephen Colbert,he spoke out against theDiamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II,stating: "It was a celebration of what? 60 years of dictatorship. She's not [my Queen]. I'm not a subject."[367]

Morrissey's first solo album,Viva Hate,included a track entitled "Margaret on the Guillotine", a jab atMargaret Thatcher.The LondonMetropolitan Policeinvestigated Morrissey as a result of the song's lyrics.[368]Followingher deathin 2013, Morrissey called her "a terror without an atom of humanity" and said "every move she made was charged by negativity".[369]He described Thatcher's successor,John Major,as "no one's idea of a Prime Minister... a terrible human mistake".[370]During theIraq War,he describedGeorge W. BushandTony Blairas "insufferable, egotistical insane despots".[173]In February 2006, Morrissey stated he had been interviewed by theFBIand byBritish intelligenceafter speaking out against the American and British governments. He said: "They were trying to determine if I was a threat to the government... it didn't take them long to realise that I'm not".[371]In 2010, he endorsed Marr's statement that Prime MinisterDavid Cameronwas forbidden to like the Smiths, criticising the Prime Minister's hobby ofstag hunting.[372]In response to theManchester Arena bombingin May 2017, Morrissey criticised Prime MinisterTheresa May,Mayor of LondonSadiq Khan,Mayor of Greater ManchesterAndy Burnham,and Elizabeth II for their statements regarding the bombing.[373][374]

European Union[edit]

In 2013, Morrissey said that he "nearly voted" for theUK Independence Party,expressing his admiration for party leaderNigel Farageand endorsing Farage'sEuroscepticismregarding UK membership of theEuropean Union.[375][376]In 2019, Morrissey said: "It's obvious that" he [Farage] would make a good prime minister—if any of us can actually remember what a good prime minister is. "[377]

In October 2016, he praised theUK's referendum on EU membershipas "magnificent" and said the BBC had "persistently denigrated" supporters of theLeave campaign.[378]In 2019, he argued that the result of the EU referendum should be respected, stating "My view has always been that the result of the referendum must be carried through. If the vote had been remain there would be absolutely no question that we would remain. In the interest of true democracy, you cannot argue against the wish of the people" and added that he found "absolutely nothing attractive about the EU."[377]

Race and support for Anne Marie Waters[edit]

Morrissey has faced ongoing accusations of racism since the early 1990s from media and commentators around the globe,[9][379][380]which were prompted by his comments, actions, and recorded material. He has constantly rejected accusations of racism, and won a libel action forcing an apology fromNME,a British music magazine, saying: "We do not believe [Morrissey] is a racist."[381]

The ones who listen to the entire song, the way I sing it, and my vocal expression know only too well that I'm no racist and glorifier of xenophobia. The phrase "England for the English" [used in the song] is in quotes, so those who call the song racist are not listening. The song tells of the sadness and regret that I feel for anyone joining such a movement [as the far-right National Front].

— Morrissey, on "The National Front Disco" (quoted in 2004).[382]

Various sources accused Morrissey of racism for making reference to theNational Front,a far-right political party, in his 1992 song "The National Front Disco"; it has been argued that this criticism ignored the ironic context of the song, which pitied rather than glorified the party's supporters.[383]According to Bret, these and other allegations of racism typically entailed decontextualising lyrics from Morrissey songs such as "Bengali in Platforms"and" Asian Rut ".[384]NMEalso accused Morrissey of racism on the basis of the imagery he employed during his 1992 performance at theMadstockfestival atFinsbury Parkin north London; Morrissey included images ofskinheadgirls as a backdrop, and wrapped himself in aUnion flag.[385]Conversely, these actions resulted in Morrissey being booed off stage by a group ofneo-Naziskinheads in the audience, who believed that he was appropriating skinhead culture.[386]

Morrissey suedNMEforlibelover a 2007 article that criticised Morrissey after he allegedly told a reporter that British identity had disappeared because of immigration.[387]He was quoted as saying: "It's very difficult [to return to England] because, although I don't have anything against people from other countries, the higher the influx into England the more the British identity disappears.... the gates of England are flooded. The country's been thrown away."[388][381]His manager described the article as a "character assassination".[387][389]In 2008,The Wordapologised in court for a piece written byDavid Quantick,which commented on the 2007NMEarticle and suggested Morrissey was a racist. Morrissey acceptedThe Word's apology.[390]The legal suit againstNMEbegan in October 2011 after Morrissey won a pre-trial hearing.[391]Morrissey's case againstNMEeditorConor McNicholasand publisherIPCwas due to have been heard in July 2012.[392]The parties settled the dispute in June 2012, withNMEissuing a public apology. Morrissey's lawyer said that "no money was sought as part of a settlement.... TheNMEapology in itself is settlement enough and it closes the case. "[381]

Morrissey's 2010 statement in which he described the Chinese as a "subspecies" in reference to their treatment of animals was criticised as racist by multiple sources.[393][394]

In October 2017, he expressed the view that the2017 UKIP leadership electionhad been rigged againstanti-IslamactivistAnne Marie Waters.[395]In April 2018 he endorsed Waters' new far-right party,For Britain,[396]subsequently wearing a party badge during several performances in New York City in 2019.[397]Morrissey's apparent support for the For Britain party saw adverts of his albumCalifornia Sonwithdrawn fromMerseyrailstations,[398][399]and several record stores refusing to stock the album.[400][401]In June 2018, Morrissey reaffirmed his support for Waters and For Britain, stating "she believes in British heritage, freedom of speech, and she wants everyone in the UK to live under the same law. I find this compelling." At the same time, Morrissey also expressed comments criticising the treatment of anti-Islam activistTommy Robinson,and said: "It's very obvious that Labour or the Tories do not believe in free speech... I mean, look at the shocking treatment of Tommy Robinson."[402][403]

In June 2019, Morrissey rejected further accusations of racism against him, saying, "The word is meaningless now. Everyone ultimately prefers their own race—does this make everyone racist?"[404]In response to his recent political comments, fellow singer-songwriterBilly Braggaccused Morrissey of dragging the legacy of Johnny Marr and the Smiths "through the dirt".[405]Nick Cavewrote an open letter defending Morrissey's right to freedom of speech to voice his beliefs, as well as arguing that his musical legacy should be kept separate from his political opinions.[406]

In January 2023, in response to rumours thatMiley Cyrushad decided to pull her vocals from the song "I Am Veronica" from his albumBonfire of Teenagersover his political views, Morrissey published a statement on his website rejecting claims that he was far-right, and further clarified his political stance;[407][408]

My politics are straightforward: I recognize realities. Some realities horrify me, and some do not, but I accept that I was not created so that others might gratify me and delight me with all that they think and do – what a turgid life that would be. I've been offended all of my life, and it has strengthened me, and I am glad. I wouldn't have the journey any other way. Only by hearing the opinions of others can we form truly rational views, and therefore we must never accept a beehive society that refuses to reflect a variety of views.

American politics[edit]

At a Dublin concert in June 2004, Morrissey commented on thedeathofRonald Reagan,saying that he would have preferred ifGeorge W. Bushhad died instead.[409]Morrissey openly criticized theWar on terrorand condemned Bush as "the world's most famous active terrorist, as he bizarrely bombs the innocent people of Iraq out of existence in the name of freedom and democracy" in hisautobiography.[410]

During a January 2008 concert, Morrissey remarked "God BlessBarack Obama"and criticisedHillary Clinton,naming her "Billary Clinton".[411]In 2015, he accused Obama of not doing enough to tacklepolice brutality,stating he could not "see him doing anything at all for the black community except warning them that they must respect the security forces."[412]He endorsed Clinton in the2016 United States presidential election,[238]although he later criticised her as "the face and voice of pooled money" and praisedBernie Sandersas "sane and intelligent", accusing the US media of paying insufficient attention to his campaign. Morrissey calledDonald Trump"Donald Thump" and accused him of not having any sympathy for the victims of theOrlando nightclub shooting.[413]When asked in a 2017 interview if he would push a button that would kill Trump if given the opportunity, he responded that he "would, for the safety of the human race."[244][414][245]He later said theUnited States Secret Servicequestioned him over his comments on Trump.[415]

Impact and legacy[edit]

BiographerDavid Brethas characterised him as an artist who divides opinion among those who love him and those who loathe him, with little space for compromise between the two.[299]The press termed him the "Pope of Mope".[299]

Fandom[edit]

Simpson stated that Morrissey had a global fan following that was unrivalled in its devotion to the singer, characterising this as "the kind of devotion that only dead stars command" normally.[416]Morrissey's fans have been described as being among the most dedicated of pop and rock fans.[417]Music magazineNMEconsiders Morrissey to be "one of the most influential artists ever", whileThe Independentsays, "Most pop stars have to be dead before they reach the iconic status he has reached in his lifetime."[418]According to Bret, Morrissey's fanbase "religiously followed his every pitfall and triumph".[299]Simpson highlighted an example during the US leg of Morrissey's 1996Maladjustedtour in which young men asked the singer toautographtheir necks, which they subsequently had permanently tattooed into their skin.[419]Rogan compared Morrissey to Wilde's characterDorian Gray"in reverse; while he slowly ages, his audience remains young".[274]Rogan also noted that while onstage, Morrissey "revels in the messianic adoration" of his fans.[274]

Soon after achieving national fame, Morrissey became a gay icon,[420][421]with Bret noting that by the start of his solo career, Morrissey already had a "massive gay following".[87]This development was influenced by the speculation around his own sexual orientation, his lyrics that dealt with such subjects as age-gap sex andrent boys,as well as the Smiths' heavy use of gay and camp imagery on their record covers.[422]Morrissey's gay following was not restricted to Western countries, for he remained popular within the Japanese gay community as well.[423]

Morrissey also has a significant Hispanic fanbase, particularly in Mexico and amongMexican Americans(Chicanos) in the western United States.[424]His music has resonated with these communities because of its similarities to the traditional Mexican music genre ofranchera,which revolves around romance, morose metaphors and slow ballads.[425]Morrissey's popularity among Hispanics became widespread knowledge after he toured Latin America for the first time in 2000.[426]Chuck Klosterman,in a 2002 profile forSpinthat analyzed Morrissey's relationship with the Latino community, theorized that Morrissey's rockabilly influences were seen as a nod to thegreaserculture popular among Latinos and that his status as the son of Irish immigrants in England resonated with immigrant families in Los Angeles.[427]

On numerous occasions, Morrissey has acknowledged his Mexican fanbase. During a 1999 concert in California, he said, "I wish I was born Mexican, but it's too late for that now." He released the song "Mexico" in 2004, which contained lyrics that condemnedwhite privilege.[428]The film25 Liveevidences a particularly strong following among the singer's Latino/Chicano fans.[429]A tribute band namedMexrrisseyperforms Morrissey covers live translated in Spanish.[430]The 2018MarvelfilmAnt-Man and the Waspcontains a scene in which the character Luis discusses how his grandmother owned a jukebox that "only played Morrissey" because of Latinos' love for his music. DirectorPeyton Reednoted that it was a "funny, really specific true-to-life detail".[431]

Several Morrisseyfansitesexist. In the early 2000s Morrissey issued a "cease and desist" notification against the fan website Morrissey-Solo for publishing claims, never proven, that Morrissey had failed to pay members of his touring personnel.[432]In 2011, he issued a lifetime concert ban against the site owner who, it was claimed, had caused "intentional distress to Morrissey and Morrissey's band" over many years.[433]Another fansite, True-To-You, enjoys a close relationship with Morrissey and functioned as his official website for statements until May 2017.[434]In April 2018, Morrissey launched his own website, Morrissey Central.[435]

Influence[edit]

Bookish, reclusive-but-pugnacious—avowedlycelibate—with an almost Puritan disdain for cheap glamour and armed with a deeply unhealthy interest in language, wit and ideas Morrissey succeeded in perverting pop music for a while and making it that most absurd of things,literary.Some were moved to talk of how much Morrissey owed that blousy Anglo-Irish nineteenth-century torch-singer and stand-up comedian Oscar Wilde, the "first pop star". Arguably, poor Oscar was merely an early failed and somewhat overweight prototype for Morrissey.

— Mark Simpson, 2004.[416]

Morrissey is routinely referred to as an influential artist, both in his solo career and with the Smiths. TheBBChas referred to him as "one of the most influential figures in the history of British pop",[436]andNMEnamed the Smiths the "most influential artist ever" in a 2002 poll, even toppingthe Beatles.[437]Rolling Stone,naming him one of the greatest singers of all time in a 2014 poll, noted that his "rejection of convention" in his vocal style and lyrics is the reason "why he redefined the sound of British rock for the past quarter-century".[293]Morrissey's enduring influence has been ascribed to his wit, the "infinite capacity for interpretation" in his lyrics,[275]and his appeal to the "constant navel gazing, reflection, solipsism" of generations of "disenfranchised youth", offering unusually intimate "companionship" to broad demographics.[438]Paul A. Woods described Morrissey as "Britain's unlikeliest rock 'n' roll star in several decades", noting that at the same time he was also "its most essential".[88]Bret described him as "probably the most intellectually gifted and imaginative lyricist of his generation",[439]listing him alongsideLeonard Cohen,Bob Dylan,andJacques Brelas being one of "themonstres sacrés".[440]

JournalistMark Simpsoncalls Morrissey "one of the greatest pop lyricists—and probablythegreatest-ever lyricist of desire—that has ever moaned "and observes that" he is fully present in his songs as few other artists are, in a way that fans of most other performers... wouldn't tolerate for a moment. "[441]Simpson also argues that "After Morrissey there could be no more pop stars. His was an impossible act to follow... [his] unrivalled knowledge of the pop canon, his unequaled imagination of what it might mean to be a pop star, and his breathtakingly perverse ambition to turn it into great art, could only exhaust the form forever".[442]