Mott insulator

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

Mott insulatorsare a class of materials that are expected toconduct electricityaccording to conventionalband theories,but turn out to beinsulators(particularly at low temperatures). These insulators fail to be correctly described by band theories of solids due to their strongelectron–electron interactions, which are not considered in conventional band theory. AMott transitionis a transition from a metal to an insulator, driven by the strong interactions between electrons.[1]One of the simplest models that can capture Mott transition is theHubbard model.

The band gap in a Mott insulator exists between bands of like character, such as 3d electron bands, whereas the band gap incharge-transfer insulatorsexists between anion and cation states.

History

[edit]Although theband theoryof solids had been very successful in describing various electrical properties of materials, in 1937Jan Hendrik de BoerandEvert Johannes Willem Verweypointed out that a variety oftransition metal oxidespredicted to be conductors byband theoryare insulators.[2]With an odd number of electrons per unit cell, thevalence bandis only partially filled, so theFermi levellies within the band. From theband theory,this implies that such a material has to be a metal. This conclusion fails for several cases, e.g.CoO,one of the strongest insulators known.[1]

Nevill MottandRudolf Peierlsalso in 1937 predicted the failing of band theory can be explained by including interactions between electrons.[3]

In 1949, in particular, Mott proposed a model forNiOas an insulator, where conduction is based on the formula[4]

- (Ni2+O2−)2→ Ni3+O2−+ Ni1+O2−.

In this situation, the formation of an energy gap preventing conduction can be understood as the competition between theCoulomb potentialUbetween 3delectrons and the transfer integraltof 3delectrons between neighboring atoms (the transfer integral is a part of thetight bindingapproximation). The totalenergy gapis then

- Egap=U− 2zt,

wherezis the number of nearest-neighbor atoms.

In general, Mott insulators occur when the repulsive Coulomb potentialUis large enough to create an energy gap. One of the simplest theories of Mott insulators is the 1963Hubbard model.The crossover from a metal to a Mott insulator asUis increased, can be predicted within the so-calleddynamical mean field theory.

Mott reviewed the subject (with a good overview) in 1968.[5]The subject has been thoroughly reviewed in a comprehensive paper by Masatoshi Imada, Atsushi Fujimori, andYoshinori Tokura.[6]A recent proposal of a "Griffiths-like phase close to the Mott transition" has been reported in the literature.[7]

Mott criterion

[edit]The Mott criterion describes thecritical pointof themetal–insulator transition.The criterion is

whereis the electron density of the material andthe effective bohr radius. The constant,according to various estimates, is 2.0, 2.78,4.0, or 4.2.

If the criterion is satisfied (i.e. if the density of electrons is sufficiently high) the material becomes conductive (metal) and otherwise it will be an insulator.[8]

Mottness

[edit]Mottismdenotes the additional ingredient, aside fromantiferromagneticordering, which is necessary to fully describe a Mott insulator. In other words, we might write:antiferromagnetic order + mottism = Mott insulator.

Thus, mottism accounts for all of the properties of Mott insulators that cannot be attributed simply to antiferromagnetism.

There are a number of properties of Mott insulators, derived from both experimental and theoretical observations, which cannot be attributed to antiferromagnetic ordering and thus constitute mottism. These properties include:

- Spectral weight transfer on the Mott scale[9][10]

- Vanishing of the single particleGreen functionalong a connected surface in momentum space in thefirst Brillouin zone[11]

- Twosign changes of theHall coefficientas electrondopinggoes fromto(band insulatorshave only one sign change at)

- The presence of a charge(withthe charge of an electron) boson at low energies[12][13]

- A pseudogap away from half-filling ()[14]

Mott transition

[edit]AMott transitionis ametal-insulator transitionincondensed matter.Due toelectric field screeningthe potential energy becomes much more sharply (exponentially) peaked around the equilibrium position of the atom and electrons become localized and can no longer conduct a current. It is named after physicistNevill Francis Mott.

Conceptual explanation

[edit]In asemiconductorat low temperatures, each 'site' (atomor group of atoms) contains a certain number ofelectronsand is electrically neutral. For an electron to move away from a site, it requires a certain amount of energy, as the electron is normally pulled back toward the (now positively charged) site byCoulomb forces.If the temperature is high enough thatof energy is available per site, theBoltzmann distributionpredicts that a significant fraction of electrons will have enough energy to escape their site, leaving anelectron holebehind and becoming conduction electrons that conductcurrent.The result is that at low temperatures a material is insulating, and at high temperatures the material conducts.

While the conduction in an n- (p-) type doped semiconductor sets in at high temperatures because the conduction (valence) band is partially filled with electrons (holes) with the original band structure being unchanged, the situation is different in the case of the Mott transition where the band structure itself changes. Mott argued that the transition must be sudden, occurring when the density of free electronsNand theBohr radiussatisfies.

Simply put, a Mott transition is a change in a material's behavior from insulating to metallic due to various factors. This transition is known to exist in various systems: mercury metal vapor-liquid, metal NH3solutions, transition metal chalcogenides and transition metal oxides.[15]In the case of transition metal oxides, the material typically switches from being a good electrical insulator to a good electrical conductor. The insulator-metal transition can also be modified by changes in temperature, pressure or composition (doping). As observed byNevill Francis Mottin his 1949 publication on Ni-oxide, the origin of this behavior is correlations between electrons and the close relationship this phenomenon has to magnetism.

The physical origin of the Mott transition is the interplay between the Coulomb repulsion of electrons and their degree of localization (band width). Once the carrier density becomes too high (e.g. due to doping), the energy of the system can be lowered by the localization of the formerly conducting electrons (band width reduction), leading to the formation of a band gap, e.g. by pressure (i.e. a semiconductor/insulator).

In a semiconductor, the doping level also affects the Mott transition. It has been observed that higher dopant concentrations in a semiconductor creates internal stresses that increase the free energy (acting as a change in pressure) of the system,[16]thus reducing the ionization energy.

The reduced barrier causes easier transfer by tunneling or by thermal emission from donor to its adjacent donor. The effect is enhanced when pressure is applied for the reason stated previously. When the transport of carriers overcomes a minimumactivation energy,the semiconductor has undergone a Mott transition and become metallic.

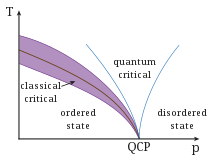

The Mott transition is usually first order, and involves discontinuous changes of physical properties. Theoretical studies of the Mott transition in the limit of large dimension find a first order transition. However in low dimensions and when the lattice geometry leads to frustration of magnetic ordering, it may be only weakly first order or even continuous (i.e second order). Weakly first order Mott transitions are seen in some quasi-two dimensional organic materials. Continuous Mott transitions have been reported in semiconductor moire materials. A theory of a continuous Mott transition is available if the Mott insulating phase is a quantum spin liquid with an emergent fermi surface of neutral fermions.

Applications

[edit]Mott insulators are of growing interest in advancedphysicsresearch, and are not yet fully understood. They have applications inthin-filmmagneticheterostructuresand the strong correlated phenomena inhigh-temperature superconductivity,for example.[17][18][19][20]

This kind ofinsulatorcan become aconductorby changing some parameters, which may be composition, pressure, strain, voltage, or magnetic field. The effect is known as aMott transitionand can be used to build smallerfield-effect transistors,switchesand memory devices than possible with conventional materials.[21][22][23]

See also

[edit]- Dynamical mean-field theory– method to determine the electronic structure of strongly correlated materials

- Electronic band structure– Describes the range of energies of an electron within the solid

- Hubbard model– Approximate model used to describe the transition between conducting and insulating systems

- Metal–insulator transition– Change between conductive and non-conductive state

- Tight binding– Model of electronic band structures of solids

- Variable-range hopping(Mott)

Notes

[edit]- ^abFazekas, Patrik (2008).Lecture notes on electron correlation and magnetism.World Scientific. pp. 147–150.ISBN978-981-02-2474-5.OCLC633481726.

- ^de Boer, J. H.; Verwey, E. J. W. (1937). "Semi-conductors with partially and with completely filled 3d-lattice bands ".Proceedings of the Physical Society.49(4S): 59.Bibcode:1937PPS....49...59B.doi:10.1088/0959-5309/49/4S/307.

- ^Mott, N. F.; Peierls, R. (1937). "Discussion of the paper by de Boer and Verwey".Proceedings of the Physical Society.49(4S): 72.Bibcode:1937PPS....49...72M.doi:10.1088/0959-5309/49/4S/308.

- ^Mott, N. F. (1949). "The basis of the electron theory of metals, with special reference to the transition metals".Proceedings of the Physical Society.Series A.62(7): 416–422.Bibcode:1949PPSA...62..416M.doi:10.1088/0370-1298/62/7/303.

- ^MOTT, N. F. (1 September 1968). "Metal-Insulator Transition".Reviews of Modern Physics.40(4). American Physical Society (APS): 677–683.Bibcode:1968RvMP...40..677M.doi:10.1103/revmodphys.40.677.ISSN0034-6861.

- ^M. Imada; A. Fujimori; Y. Tojura (1998). "Metal-Insulator Transitions".Rev. Mod. Phys.70(4): 1039.Bibcode:1998RvMP...70.1039I.doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.70.1039.

- ^Mello, Isys F.; Squillante, Lucas; Gomes, Gabriel O.; Seridonio, Antonio C.; De Souza, Mariano (2020). "Griffiths-like phase close to the Mott transition".Journal of Applied Physics.128(22): 225102.arXiv:2003.11866.Bibcode:2020JAP...128v5102M.doi:10.1063/5.0018604.S2CID214667402.

- ^Kittel, Charles (2005),Introduction to Solid State Physics(8th ed.), John Wiley & Sons, p.407–409,ISBN0-471-41526-X

- ^Phillips, Philip (2006). "Mottness".Annals of Physics.321(7). Elsevier BV: 1634–1650.arXiv:cond-mat/0702348.Bibcode:2006AnPhy.321.1634P.doi:10.1016/j.aop.2006.04.003.ISSN0003-4916.

- ^Meinders, M. B. J.; Eskes, H.; Sawatzky, G. A. (1993-08-01). "Spectral-weight transfer: Breakdown of low-energy-scale sum rules in correlated systems".Physical Review B.48(6). American Physical Society (APS): 3916–3926.Bibcode:1993PhRvB..48.3916M.doi:10.1103/physrevb.48.3916.ISSN0163-1829.PMID10008840.

- ^Stanescu, Tudor D.; Phillips, Philip; Choy, Ting-Pong (2007-03-06). "Theory of the Luttinger surface in doped Mott insulators".Physical Review B.75(10). American Physical Society (APS): 104503.arXiv:cond-mat/0602280.Bibcode:2007PhRvB..75j4503S.doi:10.1103/physrevb.75.104503.ISSN1098-0121.S2CID119430461.

- ^Leigh, Robert G.; Phillips, Philip; Choy, Ting-Pong (2007-07-25). "Hidden Charge 2e Boson in Doped Mott Insulators".Physical Review Letters.99(4): 046404.arXiv:cond-mat/0612130v3.Bibcode:2007PhRvL..99d6404L.doi:10.1103/physrevlett.99.046404.ISSN0031-9007.PMID17678382.S2CID37595030.

- ^Choy, Ting-Pong; Leigh, Robert G.; Phillips, Philip; Powell, Philip D. (2008-01-17). "Exact integration of the high energy scale in doped Mott insulators".Physical Review B.77(1). American Physical Society (APS): 014512.arXiv:0707.1554.Bibcode:2008PhRvB..77a4512C.doi:10.1103/physrevb.77.014512.ISSN1098-0121.S2CID32553272.

- ^Stanescu, Tudor D.; Phillips, Philip (2003-07-02). "Pseudogap in Doped Mott Insulators is the Near-Neighbor Analogue of the Mott Gap".Physical Review Letters.91(1): 017002.arXiv:cond-mat/0209118.Bibcode:2003PhRvL..91a7002S.doi:10.1103/physrevlett.91.017002.ISSN0031-9007.PMID12906566.S2CID5993172.

- ^Cyrot, M. (1972). "Theory of mott transition: Applications to transition metal oxides".Journal de Physique.33(1). EDP Sciences: 125–134.CiteSeerX10.1.1.463.1403.doi:10.1051/jphys:01972003301012500.ISSN0302-0738.

- ^Bose, D. N.; B. Seishu; G. Parthasarathy; E. S. R. Gopal (1986). "Doping Dependence of Semiconductor-Metal Transition in InP at High Pressures".Proceedings of the Royal Society A.405(1829): 345–353.Bibcode:1986RSPSA.405..345B.doi:10.1098/rspa.1986.0057.JSTOR2397982.S2CID136711168.

- ^Kohsaka, Y.; Taylor, C.; Wahl, P.; et al. (August 28, 2008). "How Cooper pairs vanish approaching the Mott insulator in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ".Nature.454(7208): 1072–1078.arXiv:0808.3816.Bibcode:2008Natur.454.1072K.doi:10.1038/nature07243.PMID18756248.S2CID205214473.

- ^Markiewicz, R. S.; Hasan, M. Z.; Bansil, A. (2008-03-25). "Acoustic plasmons and doping evolution of Mott physics in resonant inelastic x-ray scattering from cuprate superconductors".Physical Review B.77(9): 094518.Bibcode:2008PhRvB..77i4518M.doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.77.094518.

- ^Hasan, M. Z.; Isaacs, E. D.; Shen, Z.-X.; Miller, L. L.; Tsutsui, K.; Tohyama, T.; Maekawa, S. (2000-06-09)."Electronic Structure of Mott Insulators Studied by Inelastic X-ray Scattering".Science.288(5472): 1811–1814.arXiv:cond-mat/0102489.Bibcode:2000Sci...288.1811H.doi:10.1126/science.288.5472.1811.ISSN0036-8075.PMID10846160.S2CID2581764.

- ^Hasan, M. Z.; Montano, P. A.; Isaacs, E. D.; Shen, Z.-X.; Eisaki, H.; Sinha, S. K.; Islam, Z.; Motoyama, N.; Uchida, S. (2002-04-16). "Momentum-Resolved Charge Excitations in a Prototype One-Dimensional Mott Insulator".Physical Review Letters.88(17): 177403.arXiv:cond-mat/0102485.Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88q7403H.doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.177403.PMID12005784.S2CID30809135.

- ^US patent 6121642,Newns, Dennis, "Junction mott transition field effect transistor (JMTFET) and switch for logic and memory applications", published 2000

- ^Zhou, You; Ramanathan, Shriram (2013-01-01). "Correlated Electron Materials and Field Effect Transistors for Logic: A Review".Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences.38(4): 286–317.arXiv:1212.2684.Bibcode:2013CRSSM..38..286Z.doi:10.1080/10408436.2012.719131.ISSN1040-8436.S2CID93921400.

- ^Son, Junwoo; et al. (2011-10-18). "A heterojunction modulation-doped Mott transistor".Applied Physics Letters.110(8): 084503–084503–4.arXiv:1109.5299.Bibcode:2011JAP...110h4503S.doi:10.1063/1.3651612.S2CID27583830.

References

[edit]- Laughlin, R. B. (1997). "A Critique of Two Metals".arXiv:cond-mat/9709195.

- Anderson, P. W.; Baskaran, G. (1997). "A Critique ofA Critique of Two Metals".arXiv:cond-mat/9711197.

- Jördens, Robert; Strohmaier, Niels; Günter, Kenneth; Moritz, Henning; Esslinger, Tilman (2008). "A Mott insulator of fermionic atoms in an optical lattice".Nature.455(7210): 204–207.arXiv:0804.4009.Bibcode:2008Natur.455..204J.doi:10.1038/nature07244.PMID18784720.S2CID4426395.