Tongue

| Tongue | |

|---|---|

The human tongue | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Pharyngeal arches,lateral lingual swelling,tuberculum impar[1] |

| System | Alimentary tract,gustatory system |

| Artery | Lingual,tonsillar branch,ascending pharyngeal |

| Vein | Lingual |

| Nerve | Sensory Anterior two-thirds:Lingual(sensation) andchorda tympani(taste) Posterior one-third:Glossopharyngeal(IX) Motor Hypoglossal(XII), exceptpalatoglossus musclesupplied by thepharyngeal plexusviavagus(X) |

| Lymph | Deep cervical,submandibular,submental |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | lingua |

| MeSH | D014059 |

| TA98 | A05.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 2820 |

| FMA | 54640 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Thetongueis amuscularorganin themouthof a typicaltetrapod.It manipulates food for chewing and swallowing as part of thedigestive process,and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surface (dorsum) is covered bytaste budshoused in numerouslingual papillae.It is sensitive and kept moist bysalivaand is richly supplied withnervesandblood vessels.The tongue also serves as a natural means of cleaning the teeth.[2]A major function of the tongue is the enabling of speech in humans andvocalizationin other animals.

The human tongue is divided into two parts, anoralpart at the front and apharyngealpart at the back. The left and right sides are also separated along most of its length by a vertical section offibrous tissue(thelingual septum) that results in a groove, the median sulcus, on the tongue's surface.

There are two groups of glossal muscles. The four intrinsic muscles alter the shape of the tongue and are not attached to bone. The four paired extrinsic muscles change the position of the tongue and are anchored to bone.

Etymology

[edit]The wordtonguederives from theOld Englishtunge,which comes fromProto-Germanic*tungōn.[3]It hascognatesin otherGermanic languages—for exampletongeinWest Frisian,tonginDutchandAfrikaans,ZungeinGerman,tungeinDanishandNorwegian,andtungainIcelandic,FaroeseandSwedish.Theueending of the word seems to be a fourteenth-century attempt to show "proper pronunciation", but it is "neither etymological nor phonetic".[3]Some used the spellingtungeandtongeas late as the sixteenth century.

In humans

[edit]Structure

[edit]

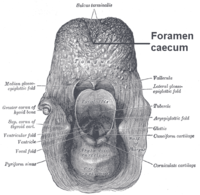

The tongue is amuscular hydrostatthat forms part of the floor of theoral cavity.The left and right sides of the tongue are separated by a vertical section of fibrous tissue known as thelingual septum.This division is along the length of the tongue save for the very back of the pharyngeal part and is visible as a groove called the median sulcus. The human tongue is divided intoanterior and posteriorparts by the terminal sulcus, which is a "V" -shaped groove. The apex of the terminal sulcus is marked by a blind foramen, the foramen cecum, which is a remnant of the medianthyroid diverticulumin earlyembryonic development.The anteriororalpart is the visible part situated at the front and makes up roughly two-thirds the length of the tongue. The posteriorpharyngealpart is the part closest to thethroat,roughly one-third of its length. These parts differ in terms of theirembryological developmentandnerve supply.

The anterior tongue is, at its apex, thin and narrow. It is directed forward against the lingual surfaces of the lowerincisorteeth. The posterior part is, at its root, directed backward, and connected with thehyoid boneby thehyoglossiandgenioglossimuscles and thehyoglossal membrane,with theepiglottisby threeglossoepiglottic foldsof mucous membrane, with thesoft palateby theglossopalatine arches,and with thepharynxby thesuperior pharyngeal constrictor muscleand themucous membrane.It also forms the anterior wall of theoropharynx.

The average length of the human tongue from theoropharynxto the tip is 10 cm.[4]The average weight of the human tongue from adult males is 99g and for adult females 79g.[5]

Inphoneticsandphonology,a distinction is made between thetipof the tongue and theblade(the portion just behind the tip). Sounds made with the tongue tip are said to beapical,while those made with the tongue blade are said to belaminal.

Upper surface

[edit]

The upper surface of the tongue is called the dorsum, and is divided by a groove into symmetrical halves by themedian sulcus.Theforamen cecummarks the end of this division (at about 2.5 cm from the root of the tongue) and the beginning of theterminal sulcus.The foramen cecum is also the point of attachment of thethyroglossal ductand is formed during the descent of thethyroid diverticuluminembryonic development.

The terminal sulcus is a shallow groove that runs forward as a shallow groove in aVshape from the foramen cecum, forwards and outwards to the margins (borders) of the tongue. The terminal sulcus divides the tongue into a posteriorpharyngealpart and an anteriororalpart. The pharyngeal part is supplied by theglossopharyngeal nerveand the oral part is supplied by thelingual nerve(a branch of the mandibular branch (V3) of thetrigeminal nerve) for somatosensory perception and by thechorda tympani(a branch of thefacial nerve) fortaste perception.

Both parts of the tongue develop from differentpharyngeal arches.

Undersurface

[edit]On the undersurface of the tongue is a fold of mucous membrane called thefrenulumthat tethers the tongue at the midline to the floor of the mouth. On either side of the frenulum are small prominences calledsublingual carunclesthat the major salivarysubmandibular glandsdrain into.

Muscles

[edit]The eight muscles of the human tongue are classified as eitherintrinsicorextrinsic.The four intrinsic muscles act to change the shape of the tongue, and are not attached to any bone. The four extrinsic muscles act to change the position of the tongue, and are anchored to bone.

Extrinsic

[edit]

The four extrinsic muscles originate from bone and extend to the tongue. They are thegenioglossus,thehyoglossus(often including thechondroglossus) thestyloglossus,and thepalatoglossus.Their main functions are altering the tongue's position allowing for protrusion, retraction, and side-to-side movement.[6]

The genioglossus arises from themandibleand protrudes the tongue. It is also known as the tongue's "safety muscle" since it is the only muscle that propels the tongue forward.

The hyoglossus, arises from thehyoid boneand retracts and depresses the tongue. The chondroglossus is often included with this muscle.

The styloglossus arises from thestyloid processof thetemporal boneand draws the sides of the tongue up to create a trough for swallowing.

The palatoglossus arises from thepalatine aponeurosis,and depresses thesoft palate,moves thepalatoglossal foldtowards the midline, and elevates the back of the tongue during swallowing.

Intrinsic

[edit]

Four paired intrinsic muscles of the tongue originate and insert within the tongue, running along its length. They are thesuperior longitudinal muscle,theinferior longitudinal muscle,thevertical muscle,and thetransverse muscle.These muscles alter the shape of the tongue by lengthening and shortening it, curling and uncurling its apex and edges as intongue rolling,and flattening and rounding its surface. This provides shape and helps facilitate speech, swallowing, and eating.[6]

The superior longitudinal muscle runs along the upper surface of the tongue under the mucous membrane, and functions to shorten and curl the tongue upward. It originates near theepiglottis,at thehyoid bone,from the median fibrous septum.

The inferior longitudinal muscle lines the sides of the tongue, and is joined to the styloglossus muscle. It functions to shorten and curl the tongue downward.

The vertical muscle is located in the middle of the tongue, and joins the superior and inferior longitudinal muscles. It functions to flatten the tongue.

The transverse muscle divides the tongue at the middle, and is attached to themucous membranesthat run along the sides. It functions to lengthen and narrow the tongue.

Blood supply

[edit]

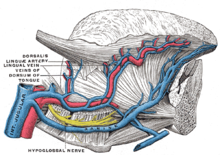

The tongue receives itsbloodsupply primarily from thelingual artery,a branch of theexternal carotid artery.Thelingual veinsdrain into theinternal jugular vein.The floor of the mouth also receives its blood supply from the lingual artery.[6]There is also a secondary blood supply to the root of tongue from thetonsillar branch of the facial arteryand theascending pharyngeal artery.

An area in the neck sometimes called thePirogov triangleis formed by the intermediate tendon of thedigastric muscle,the posterior border of themylohyoid muscle,and thehypoglossalnerve.[7][8]The lingual artery is a good place to stop severehemorrhagefrom the tongue.

Nerve supply

[edit]Innervation of the tongue consists of motor fibers,special sensoryfibers for taste, andgeneral sensoryfibers for sensation.[6]

- Motor supply for all intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue is supplied byefferent motor nerve fibersfrom thehypoglossal nerve(CN XII), with the exception of thepalatoglossus,which is innervated by thevagus nerve(CN X).[6]

Innervation of taste and sensation is different for the anterior and posterior part of the tongue because they are derived from different embryological structures (pharyngeal arch1 and pharyngeal arches 3 and 4, respectively).[9]

- Anterior two-thirds of tongue (anterior to thevallate papillae):

- Taste: chorda tympani branch of thefacial nerve(CN VII) viaspecial visceral afferentfibers

- Sensation: lingual branch of the mandibular (V3) division of thetrigeminal nerve(CN V) viageneral visceral afferentfibers

- Posterior one third of tongue:

- Taste and sensation:glossopharyngeal nerve(CN IX) via a mixture of special and general visceral afferent fibers

- Base of tongue

- Taste and sensation: internal branch of thesuperior laryngeal nerve(itself a branch of thevagus nerve,CN X)

Lymphatic drainage

[edit]The tip of tongue drains to the submental nodes. The left and right halves of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue drains tosubmandibular lymph nodes,while the posterior one-third of the tongue drains to the jugulo-omohyoid nodes.

Microanatomy

[edit]

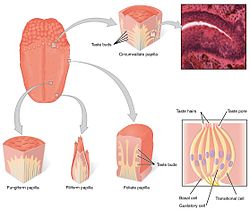

The upper surface of the tongue is covered inmasticatory mucosa,a type oforal mucosa,which is ofkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium.Embedded in this are numerouspapillae,some of which house thetaste budsand theirtaste receptors.[10]The lingual papillae consist offiliform,fungiform,vallateandfoliate papillae,[6]and only the filiform papillae are not associated with any taste buds.

The tongue can divide itself in dorsal and ventral surface. The dorsal surface is a stratified squamous keratinized epithelium, which is characterized by numerous mucosal projections called papillae.[11]The lingual papillae covers the dorsal side of the tongue towards the front of the terminal groove. The ventral surface is stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium which is smooth.[12]

Development

[edit]

The tongue begins to develop in the fourth week ofembryonic developmentfrom a median swelling – themedian tongue bud(tuberculum impar) of thefirst pharyngeal arch.[13]

In the fifth week a pair oflateral lingual swellings,one on the right side and one on the left, form on the first pharyngeal arch. These lingual swellings quickly expand and cover the median tongue bud. They form the anterior part of the tongue that makes up two-thirds of the length of the tongue, and continue to develop throughprenatal development.The line of their fusion is marked by themedian sulcus.[13]

In the fourth week, a swelling appears from the secondpharyngeal arch,in the midline, called thecopula.During the fifth and sixth weeks, the copula is overgrown by a swelling from the third and fourth arches (mainly from the third arch) called thehypopharyngeal eminence,and this develops into the posterior part of the tongue (the other third and the posterior most part of the tongue is developed from the fourth pharyngeal arch). The hypopharyngeal eminence develops mainly by the growth ofendodermfrom the third pharyngeal arch. The boundary between the two parts of the tongue, the anterior from the first arch and the posterior from the third arch is marked by the terminal sulcus.[13]The terminal sulcus is shaped like aVwith the tip of the V situated posteriorly. At the tip of the terminal sulcus is theforamen cecum,which is the point of attachment of thethyroglossal ductwhere the embryonicthyroidbegins to descend.[6]

Function

[edit]Taste

[edit]Chemicals that stimulatetaste receptorcells are known astastants.Once a tastant is dissolved insaliva,it can make contact with theplasma membraneof the gustatory hairs, which are the sites of tastetransduction.[14]

The tongue is equipped with manytaste budson itsdorsalsurface, and each taste bud is equipped with taste receptor cells that can sense particular classes of tastes. Distinct types of taste receptor cells respectively detect substances that are sweet, bitter, salty, sour, spicy, or taste ofumami.[15]Umami receptor cells are the least understood and accordingly are the type most intensively under research.[16]There is acommon misconceptionthat different sections of the tongue are exclusively responsible for differentbasic tastes.Although widely taught in schools in the form of thetongue map,this is incorrect; all taste sensations come from all regions of the tongue, although certain parts are more sensitive to certain tastes.[17]

Mastication

[edit]The tongue is an important accessory organ in the digestive system. The tongue is used for crushing food against the hard palate, during mastication and manipulation of food for softening prior to swallowing. Theepitheliumon the tongue's upper, or dorsal surface iskeratinised.Consequently, the tongue can grind against the hard palate without being itself damaged or irritated.[18]

Speech

[edit]The tongue is one of the primary articulators in the production ofspeech,and this is facilitated by both the extrinsic muscles that move the tongue and the intrinsic muscles that change its shape. Specifically, differentvowelsarearticulatedby changing the tongue's height and retraction to alter theresonantproperties of thevocal tract.These resonant properties amplify specificharmonic frequencies(formants) that are different for each vowel, while attenuating other harmonics. For example, [a] is produced with the tonguelowered and centeredand [i] is produced with the tongueraised and fronted.Consonantsare articulated by constricting airflow through the vocal tract, and many consonants feature a constriction between the tongue and some other part of the vocal tract. For example,alveolar consonantslike [s] and [n] are articulated with the tongue against thealveolar ridge,whilevelar consonantslike [k] and [g] are articulated with the tongue dorsum against the soft palate (velum). Tongue shape is also relevant to speech articulation, for example inretroflex consonants,where the tip of the tongue is curved backward.

Intimacy

[edit]The tongue plays a role inphysical intimacyandsexuality.The tongue is part of theerogenous zoneof the mouth and can be used in intimate contact, as in theFrench kissand inoral sex.

Clinical significance

[edit]Disease

[edit]Acongenital disorderof the tongue is that ofankyloglossiaalso known astongue-tie.The tongue istiedto the floor of the mouth by a very short and thickenedfrenulumand this affects speech, eating, and swallowing.

The tongue is prone to severalpathologiesincludingglossitisand otherinflammationssuch asgeographic tongue,andmedian rhomboid glossitis;burning mouth syndrome,oral hairy leukoplakia,oral candidiasis(thrush),black hairy tongue,bifid tongue (due to failure in fusion of two lingual swellings of first pharyngeal arch) andfissured tongue.

There are several types oforal cancerthat mainly affect the tongue. Mostly these aresquamous cell carcinomas.[19][20]

Food debris,desquamatedepithelial cellsandbacteriaoften form a visible tongue coating.[21]This coating has been identified as a major factor contributing tobad breath(halitosis),[21]which can be managed by using atongue cleaner.

Medication delivery

[edit]Thesublingualregion underneath the front of the tongue is an ideal location for theadministrationof certain medications into the body. Theoral mucosais very thin underneath the tongue, and is underlain by a plexus of veins. The sublingual route takes advantage of the highlyvascularquality of the oral cavity, and allows for the speedy application of medication into the cardiovascular system, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract. This is the only convenient and efficaciousroute of administration(apart fromIntravenous therapy) ofnitroglycerinto a patient suffering chest pain fromangina pectoris.

Other animals

[edit]

The muscles of the tongue evolved inamphibiansfromoccipitalsomites.Most amphibians show a proper tongue after theirmetamorphosis.[22]As a consequence, mosttetrapodanimals—amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals—have tongues (thefrogfamily ofpipidslack tongue). In mammals such asdogsandcats,the tongue is often used to clean the fur and body bylicking.The tongues of these species have a very rough texture, which allows them to remove oils and parasites. Some dogs have a tendency to consistently lick a part of their foreleg, which can result in askin conditionknown as alick granuloma.A dog's tongue also acts as a heat regulator. As a dog increases its exercise the tongue will increase in size due to greater blood flow. The tongue hangs out of the dog's mouth and the moisture on the tongue will work to cool the bloodflow.[23][24]

Some animals have tongues that are specially adapted for catching prey. For example,chameleons,frogs,pangolinsandanteatershaveprehensiletongues.

Other animals may have organs that areanalogousto tongues, such as abutterfly'sproboscisor aradulaon amollusc,but these are nothomologouswith the tongues found in vertebrates and often have little resemblance in function. For example, butterflies do not lick with their proboscides; they suck through them, and the proboscis is not a single organ, but two jaws held together to form a tube.[25]Many species of fish have small folds at the base of their mouths that might informally be called tongues, but they lack a muscular structure like the true tongues found in mosttetrapods.[26][27]

Society and culture

[edit]Figures of speech

[edit]The tongue can serve as ametonymforlanguage.For example, theNew Testamentof the Bible, in the Book ofActs of the Apostles,Jesus' disciples on the Day ofPentecostreceived a type ofspiritual gift:"there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with theHoly Ghost,and began to speak with other tongues.... ", which amazed the crowd ofJewishpeople inJerusalem,who were from various parts of theRoman Empirebut could now understand what was being preached. The phrasemother tongueis used as a child's first language. Many languages[28]have the same word for "tongue" and "language",as did theEnglish languagebefore theMiddle Ages.

A common temporary failure in wordretrievalfrommemoryis referred to as thetip-of-the-tonguephenomenon.The expressiontongue in cheekrefers to a statement that is not to be taken entirely seriously – something said or done with subtle ironic or sarcastic humour. Atongue twisteris a phrase very difficult to pronounce. Aside from being amedical condition,"tongue-tied" means being unable to say what you want due to confusion or restriction. The phrase "cat got your tongue" refers to when a person is speechless. To "bite one's tongue" is a phrase which describes holding back an opinion to avoid causing offence. A "slip of the tongue" refers to an unintentional utterance, such as aFreudian slip.The "gift of tongues" refers to when one is uncommonly gifted to be able to speak in a foreign language, often as a type ofspiritual gift.Speaking in tonguesis a common phrase used to describeglossolalia,which is to make smooth, language-resembling sounds that is no true spoken language itself. A deceptive person is said to have aforked tongue,and a smooth-talking person is said to have asilver tongue.

Gestures

[edit]Sticking one's tongue out at someone is considered a childish gesture ofrudenessor defiance in many countries; the act may also have sexual connotations, depending on the way in which it is done. However, inTibetit is considered a greeting.[29]In 2009, a farmer fromFabriano,Italy, was convicted and fined byItaly's highest courtfor sticking his tongue out at a neighbor with whom he had been arguing - proof of the affront had been captured with a cell-phone camera.[30]

Body art

[edit]Tongue piercingandsplittinghave become more common in western countries in recent decades.[when?]One study found that one-fifth of young adults in Israel had at least one type of oral piercing, most commonly the tongue.[31]

Representational art

[edit]Protruding tongues appear in the art of severalPolynesian cultures.[32]

As food

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(October 2022) |

The tongues of some animals are consumed and sometimes prized as delicacies. Hot-tongue sandwiches frequently appear on menus inkosherdelicatessensin America.Taco de lengua(lenguabeing Spanish for tongue) is a taco filled withbeef tongue,and is especially popular in Mexican cuisine. As part of Colombian gastronomy, Tongue in Sauce (Lengua en Salsa) is a dish prepared by frying the tongue and adding tomato sauce, onions and salt. Tongue can also be prepared asbirria.Pig and beef tongue are consumed in Chinese cuisine.Ducktongues are sometimes employed inSichuandishes, whilelamb's tongue is occasionally employed in Continental and contemporary American cooking. Friedcod"tongue" is a relatively common part of fish meals inNorwayand inNewfoundland.InArgentinaandUruguaycow tongue is cooked and served in vinegar (lengua a la vinagreta). In the Czech Republic and in Poland, a pork tongue is considered a delicacy, and there are many ways of preparing it. In Eastern Slavic countries, pork and beef tongues are commonly consumed, boiled and garnished with horseradish or jellied; beef tongues fetch a significantly higher price and are considered more of a delicacy. In Alaska, cow tongues are among the more common. Both cow and moose tongues are popular toppings on open-top-sandwiches in Norway, the latter usually amongst hunters.

Tongues of seals and whales have been eaten, sometimes in large quantities, by sealers and whalers, and in various times and places have been sold for food on shore.[33][page needed]

Gallery

[edit]-

Human tongue

-

Spots on the tongue

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Pennisi, Elizabeth (May 26, 2023)."How the tongue shaped life on Earth".Science.380(6647). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 786–791.doi:10.1126/science.adi8563.PMID37228192.Retrieved25 June2023.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in thepublic domainfrompage 1125of the 20th edition ofGray's Anatomy(1918)

This article incorporates text in thepublic domainfrompage 1125of the 20th edition ofGray's Anatomy(1918)

- ^hednk-024—Embryo Images atUniversity of North Carolina

- ^Maton, Anthea; Hopkins, Jean; McLaughlin, Charles William; Johnson, Susan; Warner, Maryanna Quon; LaHart, David; Wright, Jill D. (1993).Human Biology and Health.Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, US: Prentice Hall.ISBN0-13-981176-1.

- ^ab"Tongue".Online Etymology Dictionary.Retrieved17 September2017.

- ^Kerrod, Robin (1997).MacMillan's Encyclopedia of Science.Vol. 6. Macmillan Publishing Company, Inc.ISBN0-02-864558-8.

- ^Nashi, Nadia (Aug 2007)."Lingual fat at autopsy".Laryngoscope.117(8): 1467–1473.doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e318068b566.PMID17592392.Retrieved30 August2023.

- ^abcdefgDrake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M. (2005).Gray's anatomy for students.Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier. pp. 989–995.ISBN978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^"Pirogov's triangle".Whonamedit? - A dictionary of medical eponyms.Ole Daniel Enersen.

- ^Jamrozik, T.; Wender, W. (January 1952). "Topographic anatomy of lingual arterial anastomoses; Pirogov-Belclard's triangle".Folia Morphologica.3(1): 51–62.PMID13010300.

- ^Dudek, Dr Ronald W. (2014).Board Review Series: Embryology(Sixth ed.). LWW.ISBN978-1451190380.

- ^Bernays, Elizabeth; Chapman, Reginald."taste bud anatomy".Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^Fiore, Mariano; Eroschenko, Victor (2000).Di Fiore's atlas of histology with functional correlations(PDF).Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 238. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 21 June 2017.

- ^Hib, José (2001).Histología de Di Fiore: texto y atlas.Buenos Aires: El Ateneo. p.189.ISBN950-02-0386-3.

- ^abcLarsen, William J. (2001).Human embryology(Third ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Churchill Livingstone. pp.372–374.ISBN0-443-06583-7.

- ^Tortora, Gerard J.; Derrickson, Bryan H. (2008). "17".Principles of Anatomy and Physiology(12th ed.). Wiley. p. 602.ISBN978-0470084717.

- ^Silverhorn, Dee Unglaub (2009). "10".Human Physiology: An integrated approach(5th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. p. 352.ISBN978-0321559807.

- ^Schacter, Daniel L.; Gilbert, Daniel Todd; Wegner, Daniel M. (2009). "Sensation and Perception".Psychology(2nd ed.). New York: Worth. p.166.ISBN9780716752158.

- ^O'Connor, Anahad (November 10, 2008)."The Claim: The tongue is mapped into four areas of taste".The New York Times.RetrievedJune 24,2011.

- ^Atkinson, Martin E. (2013).Anatomy for Dental Students(4th ed.). Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0199234462.

the tongue is also responsible for the shaping of the bolus as food passes from the mouth to the rest of the alimentary canal

- ^"Oral Cancer Facts".The Oral Cancer Foundation. 28 August 2017. Archived fromthe originalon 22 June 2013.Retrieved17 September2017.

- ^Lam, L.; Logan, R. M.; Luke, C. (March 2006)."Epidemiological analysis of tongue cancer in South Australia for the 24-year period, 1977-2001"(PDF).Australian Dental Journal.51(1): 16–22.doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00395.x.hdl:2440/22632.PMID16669472.

- ^abNewman, Michael G.; Takei, Henry; Klokkevold, Perry R.; Carranza, Fermin A. (2012).Carranza's Clinical Periodontology(11th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier/Saunders. pp.84–96.ISBN978-1-4377-0416-7.

- ^Iwasaki, Shin-ichi (July 2002)."Evolution of the structure and function of the vertebrate tongue".Journal of Anatomy.201(1): 1–13.doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00073.x.ISSN0021-8782.PMC1570891.PMID12171472.

- ^"A Dog's Tongue".DrDog.com.Dr. Dog Animal Health Care Division of BioChemics. 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 2010-09-20.Retrieved2007-03-09.

- ^Krönert, H.; Pleschka, K. (January 1976). "Lingual blood flow and its hypothalamic control in the dog during panting".Pflügers Archiv: European Journal of Physiology.367(1): 25–31.doi:10.1007/BF00583652.ISSN0031-6768.PMID1034283.S2CID23295086.

- ^Richards, O. W.; Davies, R. G. (1977).Imms' General Textbook of Entomology: Volume 1: Structure, Physiology and Development, Volume 2: Classification and Biology.Berlin: Springer.ISBN0-412-61390-5.

- ^Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977).The Vertebrate Body.Philadelphia, Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 298–299.ISBN0-03-910284-X.

- ^Kingsley, John Sterling (1912).Comparative anatomy of vertebrates.P. Blackiston's Son & Co. pp.217–220.ISBN1-112-23645-7.

- ^Afrikaanstong;Danishtunge;Albaniangjuha;Armenianlezu(լեզու);Greekglóssa(γλώσσα);Irishteanga;Manxçhengey;LatinandItalianlingua;Catalanllengua;Frenchlangue;Portugueselíngua;Spanishlengua;Romanianlimba;Bulgarianezik(език);Polishjęzyk;Russianyazyk(язык);CzechandSlovakjazyk;SloveneandSerbo-Croatianjezik(језик);Kurdishziman(زمان);PersianandUrduzabān(زبان);Arabiclisān(لسان);Aramaicliššānā(ܠܫܢܐ/לשנא);Hebrewlāšon(לָשׁוֹן);Malteseilsien;Estoniankeel;Finnishkieli;Hungariannyelv;AzerbaijaniandTurkishdil;KazakhandKhakastil(тіл)

- ^Dresser, Norine (8 November 1997)."On Sticking Out Your Tongue".Los Angeles Times.Retrieved18 July2022.

- ^United Press International (19 December 2009)."Sticking out your tongue ruled illegal".Rome, Italy.Retrieved17 September2017.

- ^Liran, Levin; Yehuda, Zadik; Tal, Becker (December 2005). "Oral and dental complications of intra-oral piercing".Dent Traumatol.21(6): 341–3.doi:10.1111/j.1600-9657.2005.00395.x.PMID16262620.

- ^

Teilhet-Fisk, Jehanne, ed. (1973) [1973].Dimensions of Polynesia: Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego, October 7-November 25, 1973.Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego. p. 115.Retrieved15 April2024.

The mouth forms of Polynesia are expressive and contain a great deal of variation, from the snarling lips of Hawaiian sculture to the tight-lipped, pursed mouths of the Easter Island statues. [...] The presence or absence of a tongue is helpful in considering the meaning of the mouth forms. The mouth forms showing protrusion of the tongue occur in the Marginal Islands (New Zealand, Hawaii, and the Marquesas), Central Polynesia (Tahiti and the Cook Islands) and the Australs.

- ^Hawes, Charles Boardman (1924).Whaling.Doubleday.