Museo Nazionale Romano

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(July 2019) |

Baths of Diocletian | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Established | 1889 |

|---|---|

| Location | via Enrico de Nicola, 79 (Baths of Diocletian) largo di Villa Peretti, 1 (Palazzo Massimo alle Terme) via Sant’Apollinare, 46 (Palazzo Altemps) via delle Botteghe Oscure, 31 (Crypta Balbi) allRome,Italy |

| Coordinates | 41°54′4.51″N12°29′53.86″E/ 41.9012528°N 12.4982944°E |

| Type | archaeology |

| Director | Daniela Porro[1][2] |

| Website | Official Website |

TheNational Roman Museum(Italian:Museo Nazionale Romano) is a museum, with several branches in separate buildings throughout the city ofRome,Italy.It shows exhibits from the pre- and early history of Rome, with a focus on archaeological findings from the period ofAncient Rome.

History[edit]

Founded in 1889 and inaugurated in 1890, the museum's first aim was to collect and exhibit archaeologic materials unearthed during the excavations after the union of Rome with theKingdom of Italy.

The initial core of its collection originated from theKircherian Museum,archaeologic works assembled by theantiquarianandJesuitpriest,Athanasius Kircher,which previously had been housed within the Jesuit complex ofSant'Ignazio.The collection was appropriated by the state in 1874, after the suppression of the Society of Jesus. Renamed initially as the Royal Museum, the collection was intended to be moved to aMuseo Tiberino(Tiberine Museum), which was never completed.

In 1901 the Italian state granted the National Roman Museum the recently acquiredCollection Ludovisias well as the important national collection of Ancient Sculpture. Findings during the urban renewal of the late 19th century added to the collections.

In 1913, a ministerial decree sanctioned the division of the collection of theMuseo Kircherianoamong all the different museums that had been established over the last decades, such as the National Roman Museum, theNational Etruscan Museumof Villa Giulia and the Museum of Castel Sant'Angelo.

Its seat was established in the charterhouse designed and realised in the 16th century byMichelangelowithin theBaths of Diocletian,which currently houses the epigraphic and the protohistoric sections of the modern museum, while the main collection of ancient art was moved to the nearby Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, acquired by the Italian state in 1981.

The reconversion of the area of the ancient bath/charterhouse into an exhibition space began on the occasion of theInternational Exhibition of Art of 1911;this effort was completed in the 1930s.

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme[edit]

History of the building[edit]

The palace was built on the site once occupied by theVilla Montalto-Peretti,named afterPope Sixtus V,who had been born with the nameFrancesco Peretti di Montalto.The present building was commissioned by PrinceMassimiliano Massimo,so as to give a seat to the JesuitRoman College,originally within the convent of theChurch of St. Ignatius of Loyola at Campus Martius.In 1871, the College had been ousted from the convent by the government which converted it into theLiceo Visconti,the first secular public high school of Italy. Erected between 1883 and 1887 by the architectCamillo PistrucciinNeo-Renaissancestyle, it was one of the most prestigious schools of Rome until 1960. DuringWorld War II,it was partially used as amilitary hospital,but it then returned to scholastic functions after the war only until the 1960s, when the school was moved to a newer seat in the EUR quarter.

In 1981, when the palace was lying in a state of neglect and disrepair, theItalian Governmentacquired it for 19 billion lira and granted it to the National Roman Museum. Its restoration and adaptation began in 1983 and was completed in 1998. The palace eventually became the main seat of the museum as well as the headquarters of the Agency of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities of Italy (Italian:Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Roma), in charge for the archaeological heritage of Rome. The museum houses the ancient art (sculptures, paintings, mosaics and goldsmiths’ crafts from the Republican Age to the Late Antiquity) as well as the numismatic collection, housed in theMedagliere,i.e. the coin cabinet.

Ground floor and first floor[edit]

The ground floor features the notable bronze statues of theBoxer at Restand theAthlete.

One room is devoted to themummythat was found in 1964 on theVia Cassia,inside a richly decoratedsarcophaguswith severalartefactsinamberand pieces ofjewelleryalso on display. Sculptures of the period between the lateRoman Republicand the earlyimperial period(2nd century BC to 1st century AD), include:

- Tivoli General

- Tiber Apollo

- Tiber Dionysus

- Via Labicana Augustus

- Aphrodite of Menophantos

- Hermes LudovisifromAnzio

- Torlonia Vase

- Sleeping Hermaphroditus

- Dionysus Sardanapalus

- Portonaccio sarcophagus

Second floor[edit]

Frescoes, stuccoes and mosaics, including those from thevilla of Livia,wife ofAugustus,atPrima Portaon theVia Flaminia.It begins with the summertricliniumof Livia'sVilla ad Gallinas Albas.The frescoes, discovered in 1863 and dating back to the 1st century BC, show a luscious garden with ornamental plants andpomegranatetrees.

Basement[edit]

The Museum's numismatic collection is the largest in Italy. Among the coins on exhibit areTheodoric’smedallion,the fourducatsofPope Paul IIwith thenavicellaofSaint Peter,and the silverpiastreof thePapal Statewith views of the city ofRome.

Palazzo Altemps[edit]

History of the building[edit]

The building was designed in the 15th century byMelozzo da ForlìforGirolamo Riario,a relation ofPope Sixtus IV.There is still a fresco on one wall of the rooms in the palazzo that celebrates the wedding of Girolamo toCaterina Sforzain 1477, showing the silver plates and other wedding gifts given to the couple. When the Riario family began to decline after the death ofPope Sixtus IV,the palazzo was sold to CardinalFrancesco Soderiniof Volterra, who commissioned further refinements from the architectsSangallo the ElderandBaldassare Peruzzi.

When the Soderini family fell on hard times, he in turn sold it in 1568 to the Austrian-born cardinalMark Sittich von Hohenems Altemps,the son of the sister ofPope Pius IV.Cardinal Altemps commissioned the architectMartino Longhito expand and improve the palazzo; it was Longhi who built thebelvedere.Cardinal Altemps accumulated a large collection of books and ancient sculpture. Though his position as the second son in his family meant Marco Sittico Altemps became a cleric, he was not inclined to priesthood. His mistress bore him a son, Roberto, made Duke of Gallese. Roberto Altemps was executed for adultery in 1586 byPope Sixtus V.

The Altemps family continued to mix in the circles ofItalian nobilitythroughout the 17th century. Roberto's granddaughter Maria Cristina d'Altemps marriedIppolito Lante Montefeltro della Rovere,Duke of Bomarzo.

The Palazzo Altemps became the property of theHoly Seein the 19th century, and the building was used as a seminary for a short time. It was granted to the Italian state in 1982 and after 15 years of restoration, inaugurated as a museum in 1997.

Collections[edit]

The palazzo houses the museum's exhibits on the history of collecting (sculptures from Renaissance collections such as theBoncompagni-LudovisiandMatteicollections, including theLudovisi Ares,Ludovisi Throne,and theSuicide of a Gaul(from the samePergamongroup as theDying Gaul) and the Egyptian collection (sculptures of eastern deities). The palace also includes the historic private theatre, at present used to house temporary exhibitions, and the church of Sant' Aniceto.

Crypta Balbi[edit]

History of the building[edit]

In 1981, digging on a derelict site in theCampus Martiusbetween the churches ofSanta Caterina dei FunariandSanto Stanislao dei Polacchi,Daniel Manacorda and his team discovered the colonnadedquadriporticusof the Theatre ofLucius Cornelius Balbus,the nearbystatio annonaeand evidence of later, medieval occupation of the site. These are presented in this branch of the museum, inaugurated in 2001, which houses the archaeological remains and finds from that dig (including astuccoarch from the porticus).

Collections[edit]

As well as new material from the excavations, objects in this exhibition space come from

- the collections of the former Kircherian Museum

- the Gorga and Betti collections

- numismaticmaterial from the Gnecchi collections and the collection ofVictor Emmanuel IIIof Savoy

- collections from theRoman Forum,in particular a fresco and marblearchitravefrom the late-1930s Fascist deconstruction of the medieval church ofSant'Adrianoin theCuria senatus.

- Museum of thePalazzo Venezia

- theCapitoline Museums

- the communal Antiquarium of Rome

- frescoes removed in 1960 from the church ofSanta Maria in Via Lata.

Basement[edit]

The building's basement contains archaeological remains. Access is only by guided tour.

Ground floor[edit]

The first section ( "archaeology and history of an urban landscape" ) presents the results of the excavations, and puts them in the context of the history of the area. As well as showing the remains from the site itself, this section also tells of theMonastero di Santa Maria Domine Rose(begun nearby in the 8th century), of medieval merchants' and craftsmen's homes, of theConservatorio di Santa Caterina dei Funari(built in the mid-16th century byIgnatius of Loyolato house the daughters of Roman prostitutes) and of theBotteghe Oscure.

First floor[edit]

A second section ( "Rome from Antiquity to the Middle Ages" ) is theMuseum of Medieval Romeand illustrates the life and transformation of Rome between the 5th and 10th centuries AD.

Baths of Diocletian[edit]

Cloister of Michelangelo[edit]

The cloister of the charterhouse of the church ofSanta Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri,this is often referred to as "Michelangelo's Cloister" as he was tasked by the Pope with transforming the Baths into a church and chapterhouse. However, it is more likely that Michelangelo just came up with the layout and that a pupil of his, Giacomo del Duca, was responsible for most of the actual architecture, at least in the initial phase of construction. The cloister was built only after Michelangelo's death in 1564. Construction began in 1565 but took at least until 1600. The upper floor was finished in 1676 and the central fountain dates to 1695.[3]: 45

Inside the square of the cloister, a 16th-century garden features outdoor displays of altars and funerary sculpture and inscriptions. These notably include some colossal animal heads, several of which date from Antiquity and were found near Trajan's Column in 1586.[3]: 47

Prehistory section[edit]

On the upper floor of the cloister, this exhibit shows the development of the culture ofLatiumfrom the Bronze Age (11th century BC) to the Orientalizing Period (10th to 6th century BC) by means of archaeological findings from the region around Rome.[3]: 37

Small cloister[edit]

The small cloister of the charterhouse has been recently renovated. It occupies around a third of the area previously occupied by thenatatio(swimming pool) of the Baths of Diocletian. It was originally built alongside the church. Construction began in the mid-16th century but continued beyond the 17th century. With a side length of 40 meters (half the size of Michelangelo's Cloister) it today features exhibits on theArval Brethrenand on theSecular Games.The late 16th-century travertine well in the centre was added during the recent renovation.[3]: 53–8

Epigraphic section[edit]

Showing over 900 exhibits on inscriptions/writings, over three floors of a modern building, this collection houses over 10,000 inscriptions.[3]: 15

Aule delle Olearie[edit]

These were the storage facilities created by Pope Clement XIII in some of the former halls of the Baths of Diocletian. These large halls (numbered I to XI), most of them without roof cover, have been part of the museum since 1911.[3]: 63–72

Aula of Saint Isidore[edit]

A small square room built next to a granary knownAnnonain 1640. In 1754 it was converted into a chapel dedicated to Saint Isidore.[3]: 61–2

Octagonal Aula[edit]

This was part of the central complex of the Baths of Diocletian. It was the last of the four halls next to the caldarium. It was converted into a grain store in 1575, and in 1764 became a storage facility for oil. The dome is still the original one. The hall served as an exhibition site in 1911 but was then turned into a cinema and, in 1928, into a planetarium.[3]: 73–4

The hall was restored in 1991. It is devoted to sculptures found on baths sites in Rome.

Gallery[edit]

-

Sleeping Hermaphroditus. Marble. National Roman Museum. 2nd century BCE

-

Sleeping Hermaphroditus, front view. Marble. National Roman Museum. 2nd century BCE

-

Bust of Emperor Caracalla

-

Emperor Augustus as Pontifex Maximus

-

Sarcophagus with Muses

-

Bronze statue of a boxer resting after a bout

-

Head of Medusa in bronze

-

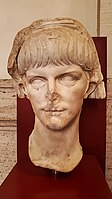

Bust of Emperor Nero at the Palazzo Massimo

-

Emperor Comodus

-

Villa of Livia garden fresco

-

Villa of Livia garden fresco

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^"Musei, ecco i 10 nuovi super direttori. Franceschini:" Eccellenze italiane "".repubblica.it.8 February 2017.Retrieved9 February2017.

- ^"Daniela Porro al Museo nazionale romano".ilsole24ore.com.8 February 2017.Retrieved9 February2017.

- ^abcdefghMinistero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo (2017).Baths of Diocletian.Mondadori Electa.ISBN978-88-918-0313-9.

External links[edit]

- Official Website of the Museo Nazionale Romano[dead link]

- Roma 2000 information

- Free downloadable PDF of the Brochure of the Museum at Palazzo Massimo

- A video depicting an Eliot poem with images of Palazzo Altemps

Media related toPalazzo Massimo alle Termeat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toPalazzo Massimo alle Termeat Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by National Etruscan Museum |

Landmarks of Rome Museo Nazionale Romano |

Succeeded by Museo Storico Nazionale dell'Arte Sanitaria |