Musical note

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(February 2022) |

Inmusic,notesare distinct and isolatablesoundsthat act as the most basic building blocks for nearly all ofmusic.Thisdiscretizationfacilitates performance, comprehension, andanalysis.[1]Notes may be visually communicated bywritingthem inmusical notation.

Notes can distinguish the generalpitch classor the specificpitchplayed by a pitchedinstrument.Although this article focuses on pitch, notes forunpitched percussion instrumentsdistinguish between different percussion instruments (and/or different manners to sound them) instead of pitch.Note valueexpresses the relativedurationof the note intime.Dynamicsfor a note indicate howloudto play them.Articulationsmay further indicate how performers should shape theattack and decayof the note and express fluctuations in a note'stimbreandpitch.Notes may even distinguish the use of differentextended techniquesby using special symbols.

The termnotecan refer to a specific musical event, for instance when saying thesong"Happy Birthday to You",begins with two notes of identical pitch. Or more generally, the term can refer to a class of identically sounding events, for instance when saying" the song begins with the same note repeated twice ".

Distinguishing duration

[edit]This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(March 2024) |

A note can have anote valuethat indicates the note'sdurationrelative to themusical meter.In order of halving duration, these values are:

| "American" name | "British" name | |

|---|---|---|

| double note | breve | |

| whole note | semibreve | |

| half note | minim | |

| quarter note | crotchet | |

| eighth note | quaver | |

| sixteenth note | semiquaver | |

| thirty-second note | demisemiquaver | |

| sixty-fourth note | hemidemisemiquaver | |

| 𝅘𝅥𝅲 | hundred twenty-eighth note | semihemidemisemiquaver, quasihemidemisemiquaver |

Longer note values (e.g. thelonga) and shorter note values (e.g. thetwo hundred fifty-sixth note) do exist, but are very rare in modern times. These durations can further besubdividedusingtuplets.

Arhythmis formed from a sequence intimeof consecutive notes (without particular focus on pitch) andrests(the time between notes) of various durations.

Distinguishing pitch

[edit]

Distinguishing pitches of a scale

[edit]Music theoryin mostEuropean countriesand others[note 1]use thesolfègenaming convention.Fixed douses thesyllablesre–mi–fa–sol–la–tispecifically for theC majorscale, whilemovable dolabels notes ofanymajor scalewith that same order of syllables.

Alternatively, particularly in English- and some Dutch-speaking regions, pitch classes are typically represented by the first seven letters of theLatin alphabet(A, B, C, D, E, F and G), corresponding to theA minorscale. Several European countries, including Germany, use H instead of B (see§ 12-tone chromatic scalefor details).Byzantiumused the namesPa–Vu–Ga–Di–Ke–Zo–Ni(Πα–Βου–Γα–Δι–Κε–Ζω–Νη).[2]

In traditionalIndian music,musical notes are calledsvarasand commonly represented using the seven notes, Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha and Ni.

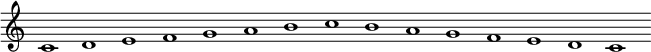

Writing notes on a staff

[edit]In ascore,each note is assigned a specific vertical position on astaff position(a line or space) on thestaff,as determined by theclef.Each line or space is assigned a note name. These names are memorized bymusiciansand allow them to know at a glance the proper pitch to play on their instruments.

Thestaffabove shows the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C and then in reverse order, with no key signature or accidentals.

Accidentals

[edit]Notes that belong to thediatonic scalerelevant in atonalcontext are calleddiatonicnotes.Notes that do not meet that criterion are calledchromaticnotesoraccidentals.Accidental symbols visually communicate a modification of a note's pitch from its tonal context. Most commonly,[note 2]thesharpsymbol (♯) raises a note by ahalf step,while theflatsymbol (♭) lowers a note by a half step. This half stepintervalis also known as asemitone(which has anequal temperamentfrequency ratio of12√2≅ 1.0595). Thenaturalsymbol (♮) indicates that any previously applied accidentals should be cancelled. Advanced musicians use thedouble-sharpsymbol (![]() ) to raise the pitch by twosemitones,thedouble-flatsymbol (

) to raise the pitch by twosemitones,thedouble-flatsymbol (![]() ) to lower it by two semitones, and even more advanced accidental symbols (e.g. forquarter tones). Accidental symbols are placed tothe rightof a note's letter when written in text (e.g. F♯isF-sharp,B♭isB-flat,and C♮isC natural), but are placed tothe leftof anote's headwhen drawn on astaff.

) to lower it by two semitones, and even more advanced accidental symbols (e.g. forquarter tones). Accidental symbols are placed tothe rightof a note's letter when written in text (e.g. F♯isF-sharp,B♭isB-flat,and C♮isC natural), but are placed tothe leftof anote's headwhen drawn on astaff.

Systematic alterations to any of the 7 letteredpitch classesare communicated using akey signature.When drawn on a staff, accidental symbols are positioned in a key signature to indicate that those alterations apply to all occurrences of the lettered pitch class corresponding to each symbol's position. Additional explicitly-noted accidentals can be drawn next to noteheads to override the key signature for all subsequent notes with the same lettered pitch class in thatbar.However, this effect does not accumulate for subsequent accidental symbols for the same pitch class.

12-tone chromatic scale

[edit]Assumingenharmonicity,accidentals can create pitch equivalences between different notes (e.g. the note B♯represents the same pitch as the note C). Thus, a 12-notechromatic scaleadds 5 pitch classes in addition to the 7 lettered pitch classes.

The following chart lists names used in different countries for the 12 pitch classes of achromatic scalebuilt on C. Their corresponding symbols are in parentheses. Differences between German and English notation are highlighted inboldtypeface. Although the English and Dutch names are different, the corresponding symbols are identical.

| English | C | Csharp (C♯) |

D | D sharp (D♯) |

E | F | F sharp (F♯) |

G | G sharp (G♯) |

A | A sharp (A♯) |

B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dflat (D♭) |

E flat (E♭) |

G flat (G♭) |

A flat (A♭) |

B flat (B♭) | ||||||||

| German[3][note 3] | C | Cis (C♯) |

D | Dis (D♯) |

E | F | Fis (F♯) |

G | Gis (G♯) |

A | Ais (A♯) |

H |

| Des (D♭) |

Es (E♭) |

Ges (G♭) |

As (A♭) |

B | ||||||||

| Swedish compromise[4] | C | Ciss (C♯) |

D | Diss (D♯) |

E | F | Fiss (F♯) |

G | Giss (G♯) |

A | Aiss (A♯) |

H |

| Dess (D♭) |

Ess (E♭) |

Gess (G♭) |

Ass (A♭) |

Bess (B♭) | ||||||||

| Dutch[3][note 4] | C | Cis (C♯) |

D | Dis (D♯) |

E | F | Fis (F♯) |

G | Gis (G♯) |

A | Ais (A♯) |

B |

| Des (D♭) |

Es (E♭) |

Ges (G♭) |

As (A♭) |

Bes (B♭) | ||||||||

| Romance languages[5][note 5] | do | do diesis (do♯) |

re | re diesis (re♯) |

mi | fa | fa diesis (fa♯) |

sol | sol diesis (sol♯) |

la | la diesis (la♯) |

si |

| re bemolle (re♭) |

mi bemolle (mi♭) |

sol bemolle (sol♭) |

la bemolle (la♭) |

si bemolle (si♭) | ||||||||

| Byzantine[6] | Ni | Ni diesis | Pa | Pa diesis | Vu | Ga | Ga diesis | Di | Di diesis | Ke | Ke diesis | Zo |

| Pa hyphesis | Vu hyphesis | Di hyphesis | Ke hyphesis | Zo hyphesis | ||||||||

| Japanese[7] | Ha (ハ) | Ei-ha (Anh ハ) |

Ni (ニ) | Ei-ni (Anh ニ) |

Ho (ホ) | He (ヘ) | Ei-he (Anh へ) |

To (ト) | Ei-to (Anh ト) |

I (イ) | Ei-i (Anh イ) |

Ro (ロ) |

| Hen-ni (変ニ) |

Hen-ho (変ホ) |

Hen-to (変ト) |

Hen-i (変イ) |

Hen-ro (変ロ) | ||||||||

| HindustaniIndian[8] | Sa (सा) |

Re Komal (रे॒) |

Re (रे) |

Ga Komal (ग॒) |

Ga (ग) |

Ma (म) |

MaTivra (म॑) |

Pa (प) |

Dha Komal (ध॒) |

Dha (ध) |

Ni Komal (नि॒) |

Ni (नि) |

| CarnaticIndian | Sa | Shuddha Ri (R1) | Chatushruti Ri (R2) | Sadharana Ga (G2) | Antara Ga (G3) | Shuddha Ma (M1) | Prati Ma (M2) | Pa | Shuddha Dha (D1) | Chatushruti Dha (D2) | Kaisika Ni (N2) | Kakali Ni (N3) |

| Shuddha Ga (G1) | Shatshruti Ri (R3) | Shuddha Ni (N1) | Shatshruti Dha (D3) | |||||||||

| BengaliIndian[9] | Sa (সা) |

Komôl Re (ঋ) |

Re (রে) |

Komôl Ga (জ্ঞ) |

Ga (গ) |

Ma (ম) |

Kôṛi Ma (হ্ম) |

Pa (প) |

Komôl Dha (দ) |

Dha (ধ) |

Komôl Ni (ণ) |

Ni (নি) |

Distinguishing pitches of different octaves

[edit]Two pitches that are any number ofoctavesapart (i.e. theirfundamental frequenciesare in a ratio equal to apower of two) are perceived as very similar. Because of that, all notes with these kinds of relations can be grouped under the samepitch classand are often given the same name.

The top note of amusical scaleis the bottom note's secondharmonicand has double the bottom note's frequency. Because both notes belong to the same pitch class, they are often called by the same name. That top note may also be referred to as the "octave"of the bottom note, since an octave is theintervalbetween a note and another with double frequency.

Scientific versus Helmholtz pitch notation

[edit]Two nomenclature systems for differentiating pitches that have the same pitch class but which fall into different octaves are:

- Helmholtz pitch notation,which distinguishes octaves usingprime symbolsandletter caseof the pitch class letter.

- The octave belowmiddleCis called the "great" octave. Notes in it and are written asupper caseletters.

- The next lower octave is named "contra". Notes in it include a prime symbol below the note's letter.

- Names of subsequent lower octaves are preceded with "sub". Notes in each include an additional prime symbol below the note's letter.

- The octave starting at middleCis called the "small" octave. Notes in it are written aslower caseletters, somiddleCitself is writtencinHelmholtz notation.

- The next higher octave is called "one-lined". Notes in it include a prime symbol above the note's letter.

- Names of subsequently higher octaves use higher numbers before the "lined". Notes in each include an addition prime symbol above the note's letter.

- The octave belowmiddleCis called the "great" octave. Notes in it and are written asupper caseletters.

- Scientific pitch notation,where a pitch class letter (C,D,E,F,G,A,B) is followed by a subscriptArabic numeraldesignating a specific octave.

- MiddleCis namedC4and is the start of the 4th octave.

- Higher octaves use successively higher number and lower octaves use successively lower numbers.

- The lowest note on most pianos isA0,the highest isC8.

- MiddleCis namedC4and is the start of the 4th octave.

For instance, the standard440 Hztuning pitch is namedA4in scientific notation and instead nameda′in Helmholtz notation.

Meanwhile, theelectronic musical instrumentstandard calledMIDIdoesn't specifically designate pitch classes, but instead names pitches by counting from its lowest note: number 0(C−1≈ 8.1758 Hz);up chromatically to its highest: number 127(G9≈ 12,544 Hz).(Although theMIDIstandardis clear, the octaves actually played by any oneMIDIdevice don't necessarily match the octaves shown below, especially in older instruments.)

Comparison of pitch naming conventions over different octaves Helmholtznotation 'Scientific'

note

namesMIDI

note

numbersFrequency of

that octave'sA

(inHertz)octave name note names sub-subcontra C„‚–B„‚ C−1–B−1 0 – 11 13.75 sub-contra C„–B„ C0–B0 12 – 23 27.5 contra C‚–B‚ C1–B1 24 – 35 55 great C–B C2–B2 36 – 47 110 small c–b C3–B3 48 – 59 220 one-lined c′–b′ C4–B4 60 – 71 440 two-lined c″–b″ C5–B5 72 – 83 880 three-lined c‴–b‴ C6–B6 84 – 95 1 760 four-lined c⁗–b⁗ C7–B7 96 – 107 3 520 five-lined c″‴–b″‴ C8–B8 108 – 119 7 040 six-lined c″⁗–b″⁗ C9–B9 120 – 127

(ends atG9)14 080

Pitch frequency in hertz

[edit]Pitch is associated with thefrequencyof physicaloscillationsmeasured inhertz(Hz) representing the number of these oscillations per second. While notes can have any arbitrary frequency, notes inmore consonantmusic tends to have pitches with simpler mathematical ratios to each other.

Western music defines pitches around a central reference "concert pitch"of A4,currently standardizedas 440 Hz. Notes playedin tunewith the12 equal temperamentsystem will be anintegernumberof half-steps above (positive) or below (negative) that reference note, and thus have a frequency of:

Octaves automatically yieldpowersof two times the original frequency, sincecan be expressed aswhenis a multiple of 12 (withbeing the number of octaves up or down). Thus the above formula reduces to yield apower of 2multiplied by 440 Hz:

Logarithmic scale

[edit]

Thebase-2 logarithmof the above frequency–pitch relation conveniently results in a linear relationship withor:

When dealing specifically with intervals (rather than absolute frequency), the constantcan be conveniently ignored, because thedifferencebetween any two frequenciesandin this logarithmic scale simplifies to:

Centsare a convenient unit for humans to express finer divisions of this logarithmic scale that are1⁄100thof an equally-temperedsemitone. Since one semitone equals 100cents,one octave equals 12 ⋅ 100 cents = 1200 cents. Cents correspond to adifferencein this logarithmic scale, however in the regular linear scale of frequency, adding 1 cent corresponds tomultiplyinga frequency by1200√2(≅1.000578).

MIDI

[edit]For use with theMIDI(Musical Instrument Digital Interface) standard, a frequency mapping is defined by:

whereis the MIDI note number. 69 is the number of semitones between C−1(MIDI note 0) and A4.

Conversely, the formula to determine frequency from a MIDI noteis:

Pitch names and their history

[edit]This sectionmay contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience.(November 2023) |

Music notation systems have used letters of thealphabetfor centuries. The 6th century philosopherBoethiusis known to have used the first fourteen letters of the classicalLatin alphabet(theletter Jdid not exist until the 16th century),

- A B C D E F G H I K L M N O

to signify the notes of the two-octave range that was in use at the time[10]and in modernscientific pitch notationare represented as

- A2B2C3D3E3F3G3A3B3C4D4E4F4G4

Though it is not known whether this was his devising or common usage at the time, this is nonetheless calledBoethian notation.Although Boethius is the first author known to use this nomenclature in the literature,Ptolemywrote of the two-octave range five centuries before, calling it theperfect systemorcomplete system– as opposed to other, smaller-range note systems that did not contain all possible species of octave (i.e., the seven octaves starting fromA,B,C,D,E,F,andG). A modified form of Boethius' notation later appeared in theDialogus de musica(ca. 1000) by Pseudo-Odo, in a discussion of the division of themonochord.[11]

Following this, the range (or compass) of used notes was extended to three octaves, and the system of repeating lettersA–Gin each octave was introduced, these being written aslower-casefor the second octave (a–g) and double lower-case letters for the third (aa–gg). When the range was extended down by one note, to aG,that note was denoted using the Greek lettergamma(Γ), the lowest note in Medieval music notation.[citation needed](It is from this gamma that the French word for scale,gammederives,[citation needed]and the English wordgamut,from "gamma-ut".[citation needed])

The remaining five notes of the chromatic scale (the black keys on a piano keyboard) were added gradually; the first beingB♭,sinceBwas flattened in certainmodesto avoid the dissonanttritoneinterval. This change was not always shown in notation, but when written,B♭(Bflat) was written as a Latin, cursive "𝑏 ",andB♮(Bnatural) a Gothic script (known asBlackletter) or "hard-edged"𝕭.These evolved into the modern flat (♭) and natural (♮) symbols respectively. The sharp symbol arose from aƀ(barred b), called the "cancelled b".[citation needed]

In parts of Europe, including Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Hungary, Norway, Denmark, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Finland, and Iceland (and Sweden before the 1990s), theGothic𝕭transformed into the letterH(possibly forhart,German for "harsh", as opposed toblatt,German for "planar", or just because the Gothic𝕭resembles anH). Therefore, in current German music notation,His used instead ofB♮(Bnatural), andBinstead ofB♭(Bflat). Occasionally, music written inGermanfor international use will useHforBnatural andBbforBflat (with a modern-script lower-case b, instead of a flat sign,♭).[citation needed]Since aBesorB♭in Northern Europe (notatedB![]() in modern convention) is both rare and unorthodox (more likely to be expressed as Heses), it is generally clear what this notation means.

in modern convention) is both rare and unorthodox (more likely to be expressed as Heses), it is generally clear what this notation means.

In Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, French, Romanian, Greek, Albanian, Russian, Mongolian, Flemish, Persian, Arabic, Hebrew, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Turkish and Vietnamese the note names aredo–re–mi–fa–sol–la–sirather thanC–D–E–F–G–A–B.These names follow the original names reputedly given byGuido d'Arezzo,who had taken them from the first syllables of the first six musical phrases of aGregorian chantmelodyUt queant laxis,whose successive lines began on the appropriate scale degrees. These became the basis of thesolfègesystem. For ease of singing, the nameutwas largely replaced bydo(most likely from the beginning ofDominus,"Lord" ), thoughutis still used in some places. It was the Italian musicologist and humanistGiovanni Battista Doni(1595–1647) who successfully promoted renaming the name of the note fromuttodo.For the seventh degree, the namesi(fromSancte Iohannes,St. John,to whom the hymn is dedicated), though in some regions the seventh is namedti(again, easier to pronounce while singing).[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^Solfègeis used inAlbania,Belgium,Bulgaria,France,Greece,Italy,Lithuania,Portugal,Romania,Russia,Spain,Turkey,Ukraine,mostLatin American countries,Arabic-speaking and Persian-speaking countries.

- ^Another style of notation, rarely used in English, uses the suffix "is" to indicate a sharp and "es" (only "s" after A and E) for a flat (e.g. Fis for F♯, Ges for G♭, Es for E♭). This system first arose in Germany and is used in almost all European countries whose main language is not English, Greek, or a Romance language (such as French, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and Romanian). In most countries using these suffixes, the letter H is used to represent what is B natural in English, the letter B is used instead of B♭, and Heses (i.e., H) is used instead of B (although Bes and Heses both denote the English B). Dutch-speakers in Belgium and the Netherlands use the same suffixes, but applied throughout to the notes A to G, so that B, B♭ and B have the same meaning as in English, although they are called B, Bes, and Beses instead of B, B flat and B double flat. Denmark also uses H, but uses Bes instead of Heses for B.

- ^used in Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Norway, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden.

- ^used in the Netherlands, and sometimes in Scandinavia after the 1990s, and Indonesia.

- ^used in Italy (diesis/bemolleare Italian spellings), France, Spain, Romania, Russia, Latin America, Greece, Israel, Turkey, Latvia and many other countries.

References

[edit]- ^Nattiez 1990,p. 81, note 9.

- ^Savas I. Savas (1965).Byzantine Music in Theory and in Practice.Translated by Nicholas Dufault. Hercules Press.

- ^ab-is=sharp;-es(after consonant) and-s(after vowel) =flat

- ^-iss=sharp;-ess(after consonant) and-ss(after vowel) =flat

- ^diesis=sharp;bemolle=flat

- ^diesis(ordiez) =sharp;hyphesis=flat

- ^Anh(ei) =♯(sharp);変(hen) =♭(flat)

- ^According toBhatkhandeNotation.Tivra=♯(sharp);Komal=♭(flat)

- ^According to Akarmatrik Notation (আকারমাত্রিক স্বরলিপি). Kôṛi =♯(sharp); Komôl =♭(flat)

- ^Boethius, A.M.S.[[scores:De institutione musica (Boëthius, Anicius Manlius Severinus) |De institutione musica]]: text at theInternational Music Score Library Project.Gottfried FriedleinBoethius.Book IV, chapter 14, page 341.

- ^Browne, Alma Colk (1979).Medieval letter notations: A survey of the sources(Ph.D. thesis). Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois.

Bibliography

[edit]- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques(1990) [1987].Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music[Musicologie générale et sémiologie]. Translated byCarolyn Abbate.Princeton University Press.ISBN0-691-02714-5.

External links

[edit]- Converter: Frequencies to note name, ± cents

- Note names, keyboard positions, frequencies and MIDI numbers

- Music notation systems − Frequencies of equal temperament tuning – The English and American system versus the German system

- Frequencies of musical notes

- Learn How to Read Sheet Music

- Free music paper for printing and downloading