Cardiac muscle

| Cardiac muscle | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Part of | Theheart wall |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | textus muscularis striatus cardiacus |

| MeSH | D009206 |

| TA98 | A12.1.06.001 |

| TA2 | 3950 |

| FMA | 9462 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

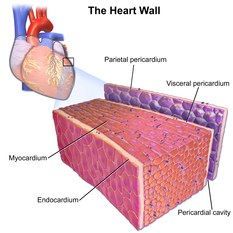

Cardiac muscle(also calledheart muscleormyocardium) is one of three types ofvertebratemuscle tissues,the others beingskeletal muscleandsmooth muscle.It is an involuntary,striated musclethat constitutes the main tissue of thewall of the heart.The cardiac muscle (myocardium) forms a thick middle layer between the outer layer of the heart wall (thepericardium) and the inner layer (theendocardium), with blood supplied via thecoronary circulation.It is composed of individual cardiac muscle cells joined byintercalated discs,and encased bycollagen fibersand other substances that form theextracellular matrix.

Cardiac musclecontractsin a similar manner toskeletal muscle,although with some important differences. Electrical stimulation in the form of acardiac action potentialtriggers the release of calcium from the cell's internal calcium store, thesarcoplasmic reticulum.The rise in calcium causes the cell'smyofilamentsto slide past each other in a process calledexcitation-contraction coupling. Diseases of the heart muscle known ascardiomyopathiesare of major importance. These includeischemicconditions caused by a restricted blood supply to the muscle such asangina,andmyocardial infarction.

Structure

[edit]Gross anatomy

[edit]

Cardiac muscle tissue or myocardium forms the bulk of the heart. The heart wall is a three-layered structure with a thick layer of myocardium sandwiched between the innerendocardiumand the outerepicardium(also known as the visceral pericardium). The inner endocardium lines the cardiac chambers, covers thecardiac valves,and joins with theendotheliumthat lines the blood vessels that connect to the heart. On the outer aspect of the myocardium is theepicardiumwhich forms part of thepericardial sacthat surrounds, protects, and lubricates the heart.[1]

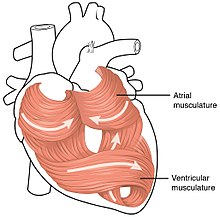

Within the myocardium, there are several sheets of cardiac muscle cells or cardiomyocytes. The sheets of muscle that wrap around the left ventricle closest to the endocardium are oriented perpendicularly to those closest to the epicardium. When these sheets contract in a coordinated manner they allow the ventricle to squeeze in several directions simultaneously – longitudinally (becoming shorter from apex to base), radially (becoming narrower from side to side), and with a twisting motion (similar to wringing out a damp cloth) to squeeze the maximum possible amount of blood out of the heart with each heartbeat.[2]

Contracting heart muscle uses a lot of energy, and therefore requires a constant flow of blood to provideoxygenand nutrients.Bloodis brought to the myocardium by thecoronary arteries.These originate from theaortic rootand lie on the outer or epicardial surface of the heart. Blood is then drained away by thecoronary veinsinto theright atrium.[1]

Microanatomy

[edit]

Cardiac muscle cells(also calledcardiomyocytes) are the contractilemyocytesof the cardiac muscle. The cells are surrounded by anextracellular matrixproduced by supportingfibroblastcells. Specialised modified cardiomyocytes known aspacemaker cells,set the rhythm of the heart contractions. The pacemaker cells are only weakly contractile without sarcomeres, and are connected to neighboring contractile cells viagap junctions.[3]They are located in thesinoatrial node(the primary pacemaker) positioned on the wall of theright atrium,near the entrance of thesuperior vena cava.[4]Other pacemaker cells are found in the atrioventricular node (secondary pacemaker).

Pacemaker cells carry the impulses that are responsible for the beating of the heart. They are distributed throughout the heart and are responsible for several functions. First, they are responsible for being able tospontaneously generateand send outelectrical impulses.They also must be able to receive and respond to electrical impulses from the brain. Lastly, they must be able to transfer electrical impulses from cell to cell.[5]Pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node, and atrioventricular node are smaller and conduct at a relatively slow rate between the cells. Specialized conductive cells in thebundle of His,and thePurkinje fibersare larger in diameter and conduct signals at a fast rate.[6]

The Purkinje fibers rapidly conduct electrical signals;coronary arteriesto bring nutrients to the muscle cells, andveinsand acapillarynetwork to take away waste products.[7]

Cardiac muscle cells are the contracting cells that allow the heart to pump. Each cardiomyocyte needs to contract in coordination with its neighboring cells - known as afunctional syncytium- working to efficiently pump blood from the heart, and if this coordination breaks down then – despite individual cells contracting – the heart may not pump at all, such as may occur duringabnormal heart rhythmssuch asventricular fibrillation.[8]

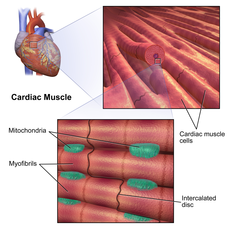

Viewed through a microscope, cardiac muscle cells are roughly rectangular, measuring 100–150μm by 30–40μm.[9]Individual cardiac muscle cells are joined at their ends byintercalated discsto form long fibers. Each cell containsmyofibrils,specialized protein contractile fibers ofactinandmyosinthat slide past each other. These are organized intosarcomeres,the fundamental contractile units of muscle cells. The regular organization of myofibrils into sarcomeres gives cardiac muscle cells a striped orstriatedappearance when looked at through a microscope, similar to skeletal muscle. These striations are caused by lighterI bandscomposed mainly of actin, and darkerA bandscomposed mainly of myosin.[7]

Cardiomyocytes containT-tubules,pouches ofcell membranethat run from the cell surface to the cell's interior which help to improve the efficiency of contraction. The majority of these cells contain only onenucleus(some may have two central nuclei), unlike skeletal muscle cells which containmany nuclei.Cardiac muscle cells contain manymitochondriawhich provide the energy needed for the cell in the form ofadenosine triphosphate(ATP), making them highly resistant to fatigue.[9][7]

T-tubules

[edit]T-tubulesare microscopic tubes that run from the cell surface to deep within the cell. They are continuous with the cell membrane, are composed of the samephospholipid bilayer,and are open at the cell surface to theextracellular fluidthat surrounds the cell. T-tubules in cardiac muscle are bigger and wider than those inskeletal muscle,but fewer in number.[9]In the centre of the cell they join, running into and along the cell as a transverse-axial network. Inside the cell they lie close to the cell's internal calcium store, thesarcoplasmic reticulum.Here, a single tubule pairs with part of the sarcoplasmic reticulum called a terminal cisterna in a combination known as adiad.[10]

The functions of T-tubules include rapidly transmitting electrical impulses known asaction potentialsfrom the cell surface to the cell's core, and helping to regulate the concentration of calcium within the cell in a process known asexcitation-contraction coupling.[9]They are also involved in mechano-electric feedback,[11]as evident from cell contraction induced T-tubular content exchange (advection-assisted diffusion),[12]which was confirmed by confocal and 3D electron tomography observations.[13]

Intercalated discs

[edit]

Thecardiac syncytiumis a network of cardiomyocytes connected byintercalated discsthat enable the rapid transmission of electrical impulses through the network, enabling the syncytium to act in a coordinated contraction of the myocardium. There is anatrial syncytiumand aventricular syncytiumthat are connected by cardiac connection fibres.[14]Electrical resistance through intercalated discs is very low, thus allowing free diffusion of ions. The ease of ion movement along cardiac muscle fibers axes is such that action potentials are able to travel from one cardiac muscle cell to the next, facing only slight resistance. Each syncytium obeys theall or none law.[15]

Intercalated discs are complex adhering structures that connect the single cardiomyocytes to an electrochemicalsyncytium(in contrast to the skeletal muscle, which becomes a multicellular syncytium duringembryonic development). The discs are responsible mainly for force transmission during muscle contraction. Intercalated discs consist of three different types of cell-cell junctions: the actin filament anchoringfascia adherens junctions,the intermediate filament anchoringdesmosomes,andgap junctions.[16]They allow action potentials to spread between cardiac cells by permitting the passage of ions between cells, producing depolarization of the heart muscle. The three types of junction act together as a singlearea composita.[16][17][18][19]

Underlight microscopy,intercalated discs appear as thin, typically dark-staining lines dividing adjacent cardiac muscle cells. The intercalated discs run perpendicular to the direction of muscle fibers. Under electron microscopy, an intercalated disc's path appears more complex. At low magnification, this may appear as a convoluted electron dense structure overlying the location of the obscured Z-line. At high magnification, the intercalated disc's path appears even more convoluted, with both longitudinal and transverse areas appearing in longitudinal section.[20]

Fibroblasts

[edit]Cardiac fibroblasts are vital supporting cells within cardiac muscle. They are unable to provide forceful contractions likecardiomyocytes,but instead are largely responsible for creating and maintaining the extracellular matrix which surrounds the cardiomyocytes.[7]Fibroblasts play a crucial role in responding to injury, such as amyocardial infarction.Following injury, fibroblasts can become activated and turn intomyofibroblasts– cells which exhibit behaviour somewhere between a fibroblast (generating extracellular matrix) and asmooth muscle cell(ability to contract). In this capacity, fibroblasts can repair an injury by creating collagen while gently contracting to pull the edges of the injured area together.[21]

Fibroblasts are smaller but more numerous than cardiomyocytes, and several fibroblasts can be attached to a cardiomyocyte at once. When attached to a cardiomyocyte they can influence the electrical currents passing across the muscle cell's surface membrane, and in the context are referred to as being electrically coupled,[22]as originally shown in vitro in the 1960s,[23]and ultimately confirmed in native cardiac tissue with the help of optogenetic techniques.[24]Other potential roles for fibroblasts include electrical insulation of thecardiac conduction system,and the ability to transform into other cell types including cardiomyocytes andadipocytes.[21]

Extracellular matrix

[edit]Theextracellular matrix(ECM) surrounds the cardiomyocyte and fibroblasts. The ECM is composed of proteins includingcollagenandelastinalong withpolysaccharides(sugar chains) known asglycosaminoglycans.[7]Together, these substances give support and strength to the muscle cells, create elasticity in cardiac muscle, and keep the muscle cells hydrated by binding water molecules.

The matrix in immediate contact with the muscle cells is referred to as thebasement membrane,mainly composed oftype IV collagenandlaminin.Cardiomyocytes are linked to the basement membrane via specialisedglycoproteinscalledintegrins.[25]

Development

[edit]Humans are born with a set number of heart muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes, which increase in size as the heart grows larger during childhood development. Evidence suggests that cardiomyocytes are slowly turned over during aging, but less than 50% of the cardiomyocytes present at birth are replaced during a normal life span.[26]The growth of individual cardiomyocytes not only occurs during normal heart development, it also occurs in response to extensive exercise (athletic heart syndrome), heart disease, or heart muscle injury such as after a myocardial infarction. A healthy adult cardiomyocyte has a cylindrical shape that is approximately 100μm long and 10–25μm in diameter. Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy occurs through sarcomerogenesis, the creation of new sarcomere units in the cell. During heart volume overload, cardiomyocytes grow through eccentric hypertrophy.[27]The cardiomyocytes extend lengthwise but have the same diameter, resulting in ventricular dilation. During heart pressure overload, cardiomyocytes grow through concentric hypertrophy.[27]The cardiomyocytes grow larger in diameter but have the same length, resulting in heart wall thickening.

Physiology

[edit]The physiology of cardiac muscle shares many similarities with that ofskeletal muscle.The primary function of both muscle types is to contract, and in both cases, a contraction begins with a characteristic flow ofionsacross thecell membraneknown as anaction potential.Thecardiac action potentialsubsequently triggers muscle contraction by increasing the concentration ofcalciumwithin the cytosol.

Cardiac cycle

[edit]Thecardiac cycleis the performance of the human heart from the beginning of one heartbeat to the beginning of the next. It consists of two periods: one during which the heart muscle relaxes and refills with blood, calleddiastole,following a period of robust contraction and pumping of blood, dubbedsystole.After emptying, the heart immediately relaxes and expands to receive another influx of blood returning from the lungs and other systems of the body, before again contracting to pump blood to the lungs and those systems. A normally performing heart must be fully expanded before it can efficiently pump again.

The rest phase is considered polarized. Theresting potentialduring this phase of the beat separates the ions such as sodium, potassium, and calcium. Myocardial cells possess the property of automaticity or spontaneousdepolarization.This is the direct result of a membrane which allows sodium ions to slowly enter the cell until the threshold is reached for depolarization. Calcium ions follow and extend the depolarization even further. Once calcium stops moving inward, potassium ions move out slowly to produce repolarization. The very slow repolarization of the CMC membrane is responsible for the long refractory period.[28][29]

However, the mechanism by which calcium concentrations within the cytosol rise differ between skeletal and cardiac muscle. In cardiac muscle, the action potential comprises an inward flow of both sodium and calcium ions. The flow of sodium ions is rapid but very short-lived, while the flow of calcium is sustained and gives the plateau phase characteristic of cardiac muscle action potentials. The comparatively small flow of calcium through theL-type calcium channelstriggers a much larger release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in a phenomenon known ascalcium-induced calcium release.In contrast, in skeletal muscle, minimal calcium flows into the cell during action potential and instead the sarcoplasmic reticulum in these cells is directly coupled to the surface membrane. This difference can be illustrated by the observation that cardiac muscle fibers require calcium to be present in the solution surrounding the cell to contract, while skeletal muscle fibers will contract without extracellular calcium.

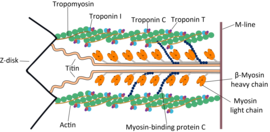

During contraction of a cardiac muscle cell, the long proteinmyofilamentsoriented along the length of the cell slide over each other in what is known as thesliding filament theory.There are two kinds of myofilaments, thick filaments composed of the proteinmyosin,and thin filaments composed of the proteinsactin,troponinandtropomyosin.As the thick and thin filaments slide past each other the cell becomes shorter and fatter. In a mechanism known ascross-bridge cycling,calcium ions bind to the protein troponin, which along with tropomyosin then uncover key binding sites on actin. Myosin, in the thick filament, can then bind to actin, pulling the thick filaments along the thin filaments. When the concentration of calcium within the cell falls, troponin and tropomyosin once again cover the binding sites on actin, causing the cell to relax.

Regeneration

[edit]

It was commonly believed that cardiac muscle cells could not be regenerated. However, this was contradicted by a report published in 2009.[30]Olaf Bergmann and his colleagues at theKarolinska InstituteinStockholmtested samples of heart muscle from people born before 1955 who had very little cardiac muscle around their heart, many showing with disabilities from this abnormality. By using DNA samples from many hearts, the researchers estimated that a 4-year-old renews about 20% of heart muscle cells per year, and about 69% of the heart muscle cells of a 50-year-old were generated after they were born.[30]

One way that cardiomyocyte regeneration occurs is through the division of pre-existing cardiomyocytes during the normal aging process.[31]

In the 2000s, the discovery of adult endogenous cardiac stem cells was reported, and studies were published that claimed that various stem cell lineages, includingbone marrow stem cellswere able to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, and could be used to treatheart failure.[32][33] However, other teams were unable to replicate these findings, and many of the original studies were laterretractedfor scientific fraud.[34][35]

Differences between atria and ventricles

[edit]

Cardiac muscle forms both the atria and the ventricles of the heart. Although this muscle tissue is very similar between cardiac chambers, some differences exist. The myocardium found in the ventricles is thick to allow forceful contractions, while the myocardium in the atria is much thinner. The individual myocytes that make up the myocardium also differ between cardiac chambers. Ventricular cardiomyocytes are longer and wider, with a denserT-tubulenetwork. Although the fundamental mechanisms of calcium handling are similar between ventricular and atrial cardiomyocytes, the calcium transient is smaller and decays more rapidly in atrial myocytes, with a corresponding increase incalcium bufferingcapacity.[36]The complement of ion channels differs between chambers, leading to longer action potential durations and effective refractory periods in the ventricles. Certain ion currents such asIK(UR)are highly specific to atrial cardiomyocytes, making them a potential target for treatments foratrial fibrillation.[37]

Clinical significance

[edit]Diseases affecting cardiac muscle, known ascardiomyopathies,are the leading cause of death indeveloped countries.[38]The most common condition iscoronary artery disease,in which theblood supply to the heart is reduced.Thecoronary arteriesbecome narrowed bythe formation of atherosclerotic plaques.[39]If these narrowings become severe enough to partially restrict blood flow, the syndrome ofanginapectoris may occur.[39]This typically causes chest pain during exertion that is relieved by rest. If a coronary artery suddenly becomes very narrowed or completely blocked, interrupting or severely reducing blood flow through the vessel, amyocardial infarctionor heart attack occurs.[40]If the blockage is not relieved promptly bymedication,percutaneous coronary intervention,orsurgery,then a heart muscle region may become permanently scarred and damaged.[41]Specific cardiomyopathies include: increasedleft ventricular mass(hypertrophic cardiomyopathy),[42]abnormally large (dilated cardiomyopathy),[43]or abnormally stiff (restrictive cardiomyopathy).[44]Some of these conditions are caused by genetic mutations and can be inherited.[45]

Heart muscle can also become damaged despite a normal blood supply. The heart muscle may become inflamed in a condition calledmyocarditis,[46]most commonly caused by a viral infection[47]but sometimes caused by the body's ownimmune system.[48]Heart muscle can also be damaged by drugs such as alcohol, long standing high blood pressure orhypertension,or persistent abnormalheart racing.[49] Many of these conditions, if severe enough, can damage the heart so much that the pumping function of the heart is reduced. If the heart is no longer able to pump enough blood to meet the body's needs, this is described asheart failure.[49]

Significant damage to cardiac muscle cells is referred to asmyocytolysiswhich is considered a type of cellularnecrosisdefined as either coagulative or colliquative.[50][51]

See also

[edit]- Frank–Starling law of the heart

- Nebulette

- Protein S100-A1

- Regional function of the heart

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

References

[edit]- ^abS., Sinnatamby, Chummy (2006).Last's anatomy: regional and applied.Last, R. J. (Raymond Jack) (11th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone.ISBN978-0-443-10032-1.OCLC61692701.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Stöhr, Eric J.; Shave, Rob E.; Baggish, Aaron L.; Weiner, Rory B. (2016-09-01)."Left ventricular twist mechanics in the context of normal physiology and cardiovascular disease: a review of studies using speckle tracking echocardiography".American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology.311(3): H633–644.doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00104.2016.hdl:10369/9408.ISSN1522-1539.PMID27402663.

- ^Neil A. Campbell; et al. (2006).Biology: concepts & connections(5th ed.). San Francisco: Pearson/Benjamin Cummings. pp.473.ISBN0-13-193480-5.

- ^Kashou AH, Basit H, Chhabra L (January 2020)."Physiology, Sinoatrial Node (SA Node)".StatPearls.PMID29083608.Retrieved10 May2020.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^"Anatomy and Physiology of the Heart".

- ^Standring, Susan (2016).Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice(Forty-first ed.). [Philadelphia]. p. 139.ISBN9780702052309.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^abcde(Pathologist), Stevens, Alan (1997).Human histology.Lowe, J. S. (James Steven), Stevens, Alan (Pathologist). (2nd ed.). London: Mosby.ISBN978-0723424857.OCLC35652355.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^The ESC textbook of cardiovascular medicine.Camm, A. John., Lüscher, Thomas F. (Thomas Felix), Serruys, P. W., European Society of Cardiology (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009.ISBN9780199566990.OCLC321015206.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^abcdM., Bers, D. (2001).Excitation-contraction coupling and cardiac contractile force(2nd ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.ISBN978-0792371588.OCLC47659382.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Hong, TingTing; Shaw, Robin M. (January 2017)."Cardiac T-Tubule Microanatomy and Function".Physiological Reviews.97(1): 227–252.doi:10.1152/physrev.00037.2015.ISSN1522-1210.PMC6151489.PMID27881552.

- ^Quinn, T. Alexander; Kohl, Peter (2021-01-01)."Cardiac Mechano-Electric Coupling: Acute Effects of Mechanical Stimulation on Heart Rate and Rhythm".Physiological Reviews.101(1): 37–92.doi:10.1152/physrev.00036.2019.ISSN0031-9333.PMID32380895.S2CID218554597.

- ^Rog-Zielinska, Eva A.; Scardigli, Marina; Peyronnet, Remi; Zgierski-Johnston, Callum M.; Greiner, Joachim; Madl, Josef; O’Toole, Eileen T.; Morphew, Mary; Hoenger, Andreas; Sacconi, Leonardo; Kohl, Peter (2021-01-22)."Beat-by-Beat Cardiomyocyte T-Tubule Deformation Drives Tubular Content Exchange".Circulation Research.128(2): 203–215.doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317266.ISSN0009-7330.PMC7834912.PMID33228470.

- ^Kohl, Peter; Greiner, Joachim; Rog-Zielinska, Eva A. (2022-04-08)."Electron microscopy of cardiac 3D nanodynamics: form, function, future".Nature Reviews Cardiology.19(9): 607–619.doi:10.1038/s41569-022-00677-x.ISSN1759-5010.PMID35396547.S2CID248004338.

- ^Jahangir Moini; Professor of Allied Health Everest University Indialantic Florida Jahangir Moini (2011).Anatomy and Physiology for Health Professionals.Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 213–.ISBN978-1-4496-3414-8.

- ^Khurana (2005).Textbook Of Medical Physiology.Elsevier India. p. 247.ISBN978-81-8147-850-4.

- ^abZhao, G; Qiu, Y; Zhang, HM; Yang, D (January 2019). "Intercalated discs: cellular adhesion and signaling in heart health and diseases".Heart Failure Reviews.24(1): 115–132.doi:10.1007/s10741-018-9743-7.PMID30288656.S2CID52919432.

- ^Franke WW, Borrmann CM, Grund C, Pieperhoff S (February 2006). "The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. I. Molecular definition in intercalated disks of cardiomyocytes by immunoelectron microscopy of desmosomal proteins".Eur. J. Cell Biol.85(2): 69–82.doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.11.003.PMID16406610.

- ^Goossens S, Janssens B, Bonné S, et al. (June 2007)."A unique and specific interaction between alphaT-catenin and plakophilin-2 in the area composita, the mixed-type junctional structure of cardiac intercalated discs".J. Cell Sci.120(Pt 12): 2126–2136.doi:10.1242/jcs.004713.hdl:1854/LU-374870.PMID17535849.

- ^Pieperhoff S, Barth M, Rickelt S, Franke WW (2010). Mahoney MG, Müller EJ, Koch PJ (eds.)."Desmosomes and Desmosomal Cadherin Function in Skin and Heart Diseases-Advancements in Basic and Clinical Research".Dermatol Res Pract.2010:1–3.doi:10.1155/2010/725647.PMC2946574.PMID20885972.

- ^Histology image:22501loafromVaughan, Deborah (2002).A Learning System in Histology: CD-ROM and Guide.Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0195151732.

- ^abIvey, Malina J.; Tallquist, Michelle D. (2016-10-25)."Defining the Cardiac Fibroblast".Circulation Journal.80(11): 2269–2276.doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-16-1003.ISSN1347-4820.PMC5588900.PMID27746422.

- ^Rohr, Stephan (June 2009). "Myofibroblasts in diseased hearts: new players in cardiac arrhythmias?".Heart Rhythm.6(6): 848–856.doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.038.ISSN1556-3871.PMID19467515.

- ^Goshima, K.; Tonomura, Y. (1969). "Synchronized beating of embryonic mouse myocardial cells mediated by FL cells in monolayer culture".Experimental Cell Research.56(2–3): 387–392.doi:10.1016/0014-4827(69)90029-9.PMID5387911.

- ^Quinn, T. Alexander; Camelliti, Patrizia; Rog-Zielinska, Eva A.; Siedlecka, Urszula; Poggioli, Tommaso; O'Toole, Eileen T.; Knöpfel, Thomas; Kohl, Peter (2016-12-20)."Electrotonic coupling of excitable and nonexcitable cells in the heart revealed by optogenetics".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.113(51): 14852–14857.Bibcode:2016PNAS..11314852Q.doi:10.1073/pnas.1611184114.ISSN0027-8424.PMC5187735.PMID27930302.

- ^Horn, Margaux A.; Trafford, Andrew W. (April 2016)."Aging and the cardiac collagen matrix: Novel mediators of fibrotic remodelling".Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology.93:175–185.doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.005.ISSN1095-8584.PMC4945757.PMID26578393.

- ^Bergmann, O.; Bhardwaj, R. D.; Bernard, S.; Zdunek, S.; Barnabe-Heider, F.; Walsh, S.; Zupicich, J.; Alkass, K.; Buchholz, B. A.; Druid, H.; Jovinge, S.; Frisen, J. (3 April 2009)."Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans".Science.324(5923): 98–102.Bibcode:2009Sci...324...98B.doi:10.1126/science.1164680.PMC2991140.PMID19342590.

- ^abGöktepe, S; Abilez, OJ; Parker, KK; Kuhl, E (2010-08-07). "A multiscale model for eccentric and concentric cardiac growth through sarcomerogenesis".Journal of Theoretical Biology.265(3): 433–442.Bibcode:2010JThBi.265..433G.doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.04.023.PMID20447409.

- ^Klabunde, Richard."Cardiovascular Physiology= Cardiac muscle Concept".

- ^"Cells Alive: Pumping Myocytes".

- ^abBergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, et al. (April 2009)."Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans".Science.324(5923): 98–102.Bibcode:2009Sci...324...98B.doi:10.1126/science.1164680.PMC2991140.PMID19342590.

- ^Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu TD, Guerguin-Kern JL, Lechene CP, Lee RT (January 2013)."Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes".Nature.493(7432): 433–436.Bibcode:2013Natur.493..433S.doi:10.1038/nature11682.PMC3548046.PMID23222518.

- ^Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel K, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Anversa P (April 2001). "Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium".Nature.410(6829): 701–705.Bibcode:2001Natur.410..701O.doi:10.1038/35070587.PMID11287958.S2CID4424399.

- ^Bolli R, Chugh AR, D'Amario D, Loughran JH, Stoddard MF, Ikram S, et al. (2011)."Cardiac stem cells in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy (SCIPIO): initial results of a randomised phase 1 trial".The Lancet.378(9806): 1847–1857.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61590-0.PMC3614010.PMID22088800.(Retracted, seedoi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30542-2,PMID30894259,Retraction Watch)

- ^Maliken B, Molkentin J (2018)."Undeniable Evidence That the Adult Mammalian Heart Lacks an Endogenous Regenerative Stem Cell".Circulation.138(8): 806–808.doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035186.PMC6205190.PMID30359129.

- ^Kolata, Gina (2018-10-29)."He Promised to Restore Damaged Hearts. Harvard Says His Lab Fabricated Research".The New York Times.

- ^Walden, A. P.; Dibb, K. M.; Trafford, A. W. (April 2009). "Differences in intracellular calcium homeostasis between atrial and ventricular myocytes".Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology.46(4): 463–473.doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.11.003.ISSN1095-8584.PMID19059414.

- ^Ravens, Ursula; Wettwer, Erich (2011-03-01)."Ultra-rapid delayed rectifier channels: molecular basis and therapeutic implications".Cardiovascular Research.89(4): 776–785.doi:10.1093/cvr/cvq398.ISSN1755-3245.PMID21159668.

- ^Lozano, Rafael; Naghavi, Mohsen; Foreman, Kyle; Lim, Stephen; Shibuya, Kenji; Aboyans, Victor; Abraham, Jerry; Adair, Timothy; Aggarwal, Rakesh (2012-12-15)."Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010".Lancet.380(9859): 2095–2128.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0.hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819.ISSN1474-547X.PMC10790329.PMID23245604.S2CID1541253.

- ^abKolh, Philippe; Windecker, Stephan; Alfonso, Fernando; Collet, Jean-Philippe; Cremer, Jochen; Falk, Volkmar; Filippatos, Gerasimos; Hamm, Christian; Head, Stuart J. (October 2014)."2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI)".European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.46(4): 517–592.doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezu366.ISSN1873-734X.PMID25173601.

- ^Smith, Jennifer N.; Negrelli, Jenna M.; Manek, Megha B.; Hawes, Emily M.; Viera, Anthony J. (March 2015)."Diagnosis and management of acute coronary syndrome: an evidence-based update".Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine.28(2): 283–293.doi:10.3122/jabfm.2015.02.140189.ISSN1558-7118.PMID25748771.

- ^Roffi, Marco; Patrono, Carlo; Collet, Jean-Philippe; Mueller, Christian; Valgimigli, Marco; Andreotti, Felicita; Bax, Jeroen J.; Borger, Michael A.; Brotons, Carlos (2016-01-14)."2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)".European Heart Journal.37(3): 267–315.doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320.hdl:10067/1526940151162165141.ISSN1522-9645.PMID26320110.

- ^Liew, Alphonsus C.; Vassiliou, Vassilios S.; Cooper, Robert; Raphael, Claire E. (2017-12-12)."Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy-Past, Present and Future".Journal of Clinical Medicine.6(12): 118.doi:10.3390/jcm6120118.ISSN2077-0383.PMC5742807.PMID29231893.

- ^Japp, Alan G.; Gulati, Ankur; Cook, Stuart A.; Cowie, Martin R.; Prasad, Sanjay K. (2016-06-28)."The Diagnosis and Evaluation of Dilated Cardiomyopathy".Journal of the American College of Cardiology.67(25): 2996–3010.doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.590.hdl:10044/1/45801.ISSN1558-3597.PMID27339497.

- ^Garcia, Mario J. (2016-05-03)."Constrictive Pericarditis Versus Restrictive Cardiomyopathy?".Journal of the American College of Cardiology.67(17): 2061–2076.doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.076.ISSN1558-3597.PMID27126534.

- ^Towbin, Jeffrey A. (2014)."Inherited cardiomyopathies".Circulation Journal.78(10): 2347–2356.doi:10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0893.ISSN1347-4820.PMC4467885.PMID25186923.

- ^Cooper, Leslie T. (2009-04-09)."Myocarditis".The New England Journal of Medicine.360(15): 1526–1538.doi:10.1056/NEJMra0800028.ISSN1533-4406.PMC5814110.PMID19357408.

- ^Rose, Noel R. (July 2016)."Viral myocarditis".Current Opinion in Rheumatology.28(4): 383–389.doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000303.ISSN1531-6963.PMC4948180.PMID27166925.

- ^Bracamonte-Baran, William; Čiháková, Daniela (2017). "Cardiac Autoimmunity: Myocarditis".The Immunology of Cardiovascular Homeostasis and Pathology.Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 1003. pp. 187–221.doi:10.1007/978-3-319-57613-8_10.ISBN978-3-319-57611-4.ISSN0065-2598.PMC5706653.PMID28667560.

- ^abPonikowski, Piotr; Voors, Adriaan A.; Anker, Stefan D.; Bueno, Héctor; Cleland, John G. F.; Coats, Andrew J. S.; Falk, Volkmar; González-Juanatey, José Ramón; Harjola, Veli-Pekka (August 2016)."2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC".European Journal of Heart Failure.18(8): 891–975.doi:10.1002/ejhf.592.hdl:2434/427148.ISSN1879-0844.PMID27207191.S2CID221675744.

- ^Baroldi, Giorgio (2004).The Etiopathogenesis of Coronary Heart Disease: A Heretical Theory Based on Morphology, Second Edition.CRC Press. p. 88.ISBN9781498712811.

- ^Olsen, E. G. (2012).Atlas of Cardiovascular Pathology.Springer Science & Business Media. p. 48.ISBN9789400932098.