Names of the Celts

The various names used sinceclassical timesfor the people known today as theCeltsare of disparate origins.

The namesΚελτοί(Keltoí) andCeltaeare used inGreekandLatin,respectively, to denote a people of theLa Tène horizonin the region of the upperRhineandDanubeduring the 6th to 1st centuries BC inGraeco-Romanethnography.The etymology of this name and that of theGaulsΓαλάταιGalátai/Galliis uncertain.

Thelinguisticsense ofCelts,a grouping of all speakers ofCeltic languages,is modern. There is scant record of the term "Celt" being used prior to the 17th century in connection with the inhabitants ofIrelandandGreat Britainduring theIron Age.However,Partheniuswrites thatCeltusdescended throughHeraclesfromBretannos,which may have been a partial (because the myth's roots are older) post–Gallic WarepithetofDruidswho traveled to the islands for formal study, and was the posited seat of the order's origins.

Celts,Celtae[edit]

The first recorded use of the name of Celts – asΚελτοί(Keltoí) – to refer to an ethnic group was byHecataeus of Miletus,the Greek geographer, in 517 BC when writing about a people living near Massilia (modernMarseille).[1]In the 5th century BC,Herodotusreferred toKeltoiliving around the head of the Danube and also in the far west of Europe.[2]

The etymology of the termKeltoiis unclear. Possible origins include theIndo-Europeanroots *ḱel,[3]'to cover or hide' (cf. Old Irishcelid[4]), *ḱel-, 'to heat', or *kel- 'to impel'.[5]Several authors have supposed the term to be Celtic in origin, while others view it as a name coined by Greeks. Linguist Patrizia De Bernardo Stempel falls in the latter group; she suggests that it means "the tall ones".[6]

The Romans preferred the nameGauls(Latin:Galli) for those Celts whom they first encountered in northernItaly(Cisalpine Gaul). In the 1st century BC, Caesar referred to the Gauls as calling themselves "Celts" in their own tongue.[7]

According to the 1st-century poetParthenius of Nicaea,Celtus(Κελτός,Keltos) was the son ofHeraclesandCeltine(Κελτίνη,Keltine), the daughter of Bretannus (Βρεττανός,Brettanos); this literary genealogy exists nowhere else and was not connected with any known cult.[8]Celtus became theeponymousancestor of Celts.[9]In Latin,Celtacame in turn fromHerodotus's word for theGauls,Keltoi.The Romans usedCeltaeto refer to continental Gauls, but apparently not toInsular Celts.The latter are divided linguistically intoGoidelsandBrythons.

The nameCeltiberiis used byDiodorus Siculusin the 1st century BC, of a people whom he considered a mixture ofCeltaeandIberi.

Celtici[edit]

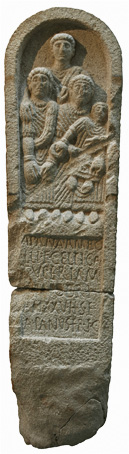

Aside from theCeltiberians—Lusones,Titii,Arevaci,andPellendones,among others – who inhabited large regions of centralSpain,Greek and Roman geographers also spoke of a people or group of peoples calledCelticiorΚελτικοίliving in the south of modern-dayPortugal,in theAlentejoregion, between theTagusandGuadianarivers.[10]They are first mentioned byStrabo,who wrote that they were the most numerous people inhabiting that region. Later, Ptolemy referred to the Celtici inhabiting a more reduced territory, comprising the regions fromÉvoratoSetúbal,i.e. the coastal and southern areas occupied by theTurdetani.

Pliny mentioned a second group of Celtici living in the region ofBaeturia(northwesternAndalusia); he considered that they were "of the Celtiberians from theLusitania,because of their religion, language, and because of the names of their cities ".[11]

InGaliciain the north of theIberian Peninsula,another group of Celtici[12]dwelt along the coasts. They comprised severalpopuli,including the Celtici proper: thePraestamaricisouth of theTambre river(Tamaris), theSupertamaricinorth of it, and theNeriiby the Celtic promontory (Promunturium Celticum).Pomponius Melaaffirmed that all inhabitants of Iberia's coastal regions, from the bays of southern Galicia to theAstures,were also Celtici: "All (this coast) is inhabited by the Celtici, except from theDouro riverto the bays, where the Grovi dwelt (…) In the north coast first there are theArtabri,still of the Celtic people (Celticae gentis), and after them theAstures."[13]He also wrote that the fabulous isles oftin,theCassiterides,were situated among these Celtici.[14]

The Celtici Supertarmarci have also left a number ofinscriptions,[15]as the Celtici Flavienses did.[16]Several villages and rural parishes still bear the nameCéltigos(from LatinCelticos) in Galicia. This is also the name of an archpriesthood of theRoman Catholic Church,a division of the archbishopric ofSantiago de Compostela,encompassing part of the lands attributed to the Celtici Supertamarici by ancient authors.[17]

Introduction in Early Modern literature[edit]

The nameCeltaewas revived in the literature of theEarly Modern period.The Frenchceltiqueand Germanceltischfirst appear in the 16th century; the English wordCeltsis first attested in 1607.[18] The adjectiveCeltic,formed after Frenchceltique,appears a little later, in the mid-17th century. An early attestation is found inMilton'sParadise Lost(1667), in reference to theInsular Celtsof antiquity:[theIoniangods... who] o'er the Celtic [fields] roamed the utmost Isles.(I.520, here in the 1674 spelling). Use ofCelticin the linguistic sense arises in the 18th century, in the work ofEdward Lhuyd.[19]

In the 18th century, the interest in "primitivism",which led to the idea of the"noble savage",brought a wave of enthusiasm for all things" Celtic. "TheantiquarianWilliam Stukeleypictured a race of "ancient Britons" constructing the "temples of the Ancient Celts" such asStonehenge(actually a pre-Celtic structure). In his 1733 bookHistory of the Temples of the Ancient Celts,he recast the "Celts" "Druids".[20]James Macpherson'sOssianfables, which he claimed were ancientScottish Gaelicpoems that he had "translated," added to this romantic enthusiasm. The "Irish revival" came after theCatholic EmancipationAct of 1829 as a conscious attempt to promote an Irish national identity, which, with its counterparts in other countries, subsequently became known as the "Celtic Revival".[20]

Pronunciation[edit]

The initial consonant of the English wordsCeltandCelticis primarily pronounced/k/and occasionally/s/in both modernBritishandAmerican English,[21][22][23][24]although/s/was formerly the norm.[25] In the oldest attestedGreekform, and originally also inLatin,it was pronounced/k/,but it was subject to a regular process ofpalatizationaround the 1st century AD whenever it appeared before afront vowellike/e/;as theLate Latinof Gaul evolved intoFrench,this palatalised sound became/t͡s/,and then developed to/s/around the end of theOld Frenchera. The/k/pronunciation of Classical Latin was later taken directly intoGerman;both pronunciations were taken into English at different times.

The English word originates in the 17th century. Until the mid-19th century, the sole pronunciation in English was/s/,in keeping with the inheritance of the letter ⟨c⟩ fromOld FrenchtoMiddle English.From the mid-19th century onward, academic publications advocated the variant with/k/on the basis of a new understanding of the word's origins. The/s/pronunciation remained standard throughout the 19th to early 20th century, but/k/gained ground during the later 20th century.[26] A notable exception is that the/s/pronunciation remains the most recognized form when it occurs in the names of sports teams, most notablyCeltic Football Clubin Scotland, and theBoston Celticsbasketball team in the United States. The title of theCavannewspaperThe Anglo-Celtis also pronounced with the/s/.[27]

Modern uses[edit]

In current usage, the terms "Celt" and "Celtic" can take several senses depending on context: theCeltsof theEuropean Iron Age,the group of Celtic-speaking peoples inhistorical linguistics,and the modernCeltic identityderived from the RomanticistCeltic Revival.

Linguistic context[edit]

After its use by Edward Lhuyd in 1707,[28]the use of the word "Celtic" as anumbrella termfor the pre-Roman peoples of theBritish Islesgained considerable popularity. Lhuyd was the first to recognise that the Irish, British, and Gaulish languages were related to one another, and the inclusion of the Insular Celts under the term "Celtic" from this time forward expresses this linguistic relationship. By the late 18th century, the Celtic languages were recognised as one branch within the larger Indo-European family.

Historiographical context[edit]

The Celts are an ethnolinguistic group of Iron Age European peoples, including theGauls(including subgroups such as theLepontiiand theGalatians),Celtiberians,andInsular Celts.

The timeline ofCeltic settlement in the British Islesis unclear and the object of much speculation, but it is clear that by the 1st century BC most of Great Britain and Ireland was inhabited by Celtic-speaking peoples now known as theInsular Celts.These peoples were divided into two large groups,Britons(speaking "P-Celtic") and Gaels (speaking" Q-Celtic "). The Brythonic groups underRomanrule were known in Latin asBritanni,while use of the namesCeltaeorGalli/Galataiwas restricted to theGauls.There are no examples of text from Goidelic languages prior to the appearance ofPrimitive Irishinscriptions in the 4th century AD; however, there are earlier references to theIverni(inPtolemyc. 150, later also appearing asHierniandHiberni) and, by 314, to theScoti.

Simon Jamesargues that while the term "Celtic" expresses a valid linguistic connection, its use for both Insular and Continental Celtic cultures is misleading, as archaeology does not suggest a unified Celtic culture during the Iron Age.[importance?][page needed]

Modern context[edit]

With the rise ofCeltic nationalismin the early to mid-19th century, the term "Celtic" also came to be a self-designation used by proponents of a modernCeltic identity.Thus, in a discussion of "the word Celt," a contributor toThe Celtstates, "The Greeks called us Keltoi,"[29]expressing a position ofethnic essentialismthat extends "we" to include both 19th-century Irish people and the Danubian Κελτοί of Herodotus. This sense of "Celtic" is preserved in its political sense in the Celtic nationalism of organisations such as theCeltic League,but it is also used in a more general and politically neutral sense in expressions such as "Celtic music."

Galli,Galatai[edit]

LatinGallimight be from an originally Celtic ethnic ortribal name,perhaps borrowed into Latin during theGallic Warsof the 4th century BCE. Its root may be the Common Celtic*galno-,meaning "power" or "strength". The GreekΓαλάταιGalatai(cf.Galatiain Anatolia) seems to be based on the same root, borrowed directly from the same hypothetical Celtic source that gave usGalli(the suffix-ataisimply indicates that the word is an ethnic name).

Linguist Stefan Schumacher presents a slightly different account: he says that the ethnonymGalli(nominative singular *Gallos) is from the present stem of the verb that hereconstructsforProto-Celticas *gal-nV-(Vdenotes a vowel whose unclear identity does not permit full reconstruction). He writes that this verb means "to be able to, to gain control of", and thatGalataicomes from the same root and is to be reconstructed as nominative singular *galatis< *gelH-ti-s.Schumacher gives the same meaning for both reconstructions, namelyGerman:Machthaber,"potentate, ruler (even warlord)", or alternativelyGerman:Plünderer, Räuber,"raider, looter, pillager, marauder"; and notes that if both names wereexonyms,it would explain theirpejorativemeanings. TheProto-Indo-Europeanverbal root in question is reconstructed by Schumacher as *gelH-,[30]meaningGerman:Macht bekommen über,"to acquire power over" in theLexikon der indogermanischen Verben.[31]

Gallaeci[edit]

The name of theGallaeci(earlier form Callaeci or Callaici), a Celtic federation in northwest Iberia, may seem related toGallibut is not. The Romans named the entire region north of theDouro,where theCastro cultureexisted, in honour of the Castro people who settled in the area of Calle – theCallaeci.[citation needed]

Gaul,Gaulish,Welsh[edit]

EnglishGaul/Gaulishare unrelated to LatinGallia/Galli,despite superficial similarity. The English words ultimately stem from the reconstructedProto-Germanicroot*walhaz,[32]"foreigner,Romanizedperson. "[33]In the early Germanic period, this exonym seems to have been applied broadly to the peasant population of theRoman Empire,most of whom lived in the areas being settled by Germanic peoples; whether the peasants spoke Celtic or Latin did not matter.

The Germanic root likely made its way into French viaLatinizationofFrankishWalholant"Gaul," literally "Land of the Foreigners". Germanicwregularly becomesgu/gin French (cf.guerre'war',garder'ward'), and thediphthongauis the regular outcome ofalbefore another consonant (cf.cheval~chevaux).GauleorGaullecan hardly be derived from LatinGallia,sincegwould becomejbeforea(gamba>jambe), and the diphthongauwould be unexplained. Note that the regular outcome of LatinGalliain French isJaille,which is found in several western placenames.[34][35]

Similarly, FrenchGallois,"Welsh," is not from LatinGallibut (with suffix substitution) from Proto-Germanic *walhisks"Celtic, Gallo-Roman, Romance" or from itsOld Englishdescendantwælisċ(= Modern EnglishWelsh).Wælisċoriginates from Proto-Germanic *walhiska-'foreign'[36]or "Celt" (South GermanWelsch(e)"Celtic speaker," "French speaker," "Italian speaker";Old Norsevalskr,pl.valir"Gaulish," "French," ). In Old French, the wordsgualeis,galois,and (Northern French)waloiscould mean either Welsh or theLangue d'oïl.However, Northern FrenchWaulleis first recorded in the 13th century to translate LatinGallia,whilegauloisis first recorded in the 15th century to translate LatinGallus/Gallicus(seeGaul: Name).

The Proto-Germanic terms may ultimately have a Celtic root:Volcae,orUolcae.[37]The Volcae were a Celtic tribe who originally lived in southern Germany and then emigrated to Gaul;[38]for two centuries they barred the southward expansion of theGermanic tribes.Most modern Celticists considerUolcaeto be related to Welshgwalch'hawk', and perhaps more distantly to Latinfalco(id.)[39]The name would have initially appeared in Proto-Germanic as*wolk-and become*walh-viaGrimm's Law.

In the Middle Ages, territories with primarilyRomance-speaking populations, such asFranceand Italy, were known in German asWelschlandin contrast toDeutschland.The Proto-Germanic root word also yieldedVlach,Wallachia,Walloon,and the second part inCornwall.The surnamesWallaceandWalshare also cognates.

Gaels[edit]

The termGaelis, despite superficial similarity, also completely unrelated to eitherGalliorGaul.The name ultimately derives from the Old Irish wordGoídel.Lenitionrendered the /d/ silent, though it still appears as⟨dh⟩in the orthography of the modern Gaelic languages ": (IrishandManx)GaedhealorGael,Scottish GaelicGàidheal.Compare also the modern linguistic termGoidelic.

Britanni[edit]

The Celtic-speaking people of Great Britain were known asBrittanniorBrittonesin Latin and as Βρίττωνες in Greek. An earlier form wasPritani,or Πρετ(τ)αν(ν)οί in Greek (as recorded byPytheasin the 4th century BC, among others, and surviving in Welsh asPrydain,the old name for Britain). Related to this is *Priteni,the reconstructed self-designation of the people later calledPicts,which is recorded later inOld IrishasCruithinand Welsh asPrydyn.

References[edit]

- ^H. D. Rankin,Celts and the classical world.Routledge, 1998. 1998. pp. 1–2.ISBN978-0-415-15090-3.Retrieved7 June2010.

- ^Herodotus,The Histories,2.33; 4.49.

- ^https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/%E1%B8%B1el-[user-generated source]

- ^"Old Irish Online".

- ^John T. Koch (ed.),Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia.5 vols. 2006, p. 371. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- ^P. De Bernardo Stempel 2008. Linguistically Celtic ethnonyms: towards a classification, inCeltic and Other Languages in Ancient Europe,J. L. García Alonso (ed.), 101-118. Ediciones Universidad Salamanca.

- ^Julius Caesar,Commentarii de Bello Gallico1.1:"All Gaul is divided into three parts, in one of which the Belgae live, another in which the Aquitani live, and the third are those who in their own tongue are called Celts (Celtae), in our language Gauls (Galli). Compare the tribal name of theCeltici.

- ^Parthenius,Love Stories2, 30

- ^"Celtine, daughter of Bretannus, fell in love with Heracles and hid away his kine (the cattle of Geryon) refusing to give them back to him unless he would first content her. From Celtus the Celtic race derived their name.""(Ref.: Parth. 30.1-2)".Retrieved5 December2005.

- ^Lorrio, Alberto J.; Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero (1 February 2005)."The Celts in Iberia: An Overview"(PDF).E-Keltoi.6:183–185. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 7 January 2012.Retrieved5 October2011.

- ^'Celticos a Celtiberis ex Lusitania advenisse manifestum est sacris, lingua, oppidorum vocabulis', NH, II.13

- ^Celtici:Pomponius Mela and Pliny;Κελτικοί:Strabo

- ^'Totam Celtici colunt, sed a Durio ad flexum Grovi, fluuntque per eos Avo, Celadus, Nebis, Minius et cui oblivionis cognomen est Limia. Flexus ipse Lambriacam urbem amplexus recipit fluvios Laeron et Ullam. Partem quae prominet Praesamarchi habitant, perque eos Tamaris et Sars flumina non-longe orta decurrunt, Tamaris secundum Ebora portum, Sars iuxta turrem Augusti titulo memorabilem. Cetera super Tamarici Nerique incolunt in eo tractu ultimi. Hactenus enim ad occidentem versa litora pertinent. Deinde ad septentriones toto latere terra convertitur a Celtico promunturio ad Pyrenaeum usque. Perpetua eius ora, nisi ubi modici recessus ac parva promunturia sunt, ad Cantabros paene recta est. In ea primum Artabri sunt etiamnum Celticae gentis, deinde Astyres.', Pomponius Mela, Chorographia, III.7-9.

- ^Pomponius Mela, Chorographia, III.40.

- ^Eburia / Calveni f(ilia) / Celtica / Sup(ertamarca) |(castello?) / Lubri; Fusca Co/edi f(ilia) Celti/ca Superta(marca) / |(castello) Blaniobr/i; Apana Ambo/lli f(ilia) Celtica / Supertam(arca) / Maiobri; Clarinu/s Clari f(ilius) Celticus Su/pertama(ricus). Cf.Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss / SlabyArchived25 August 2011 at theWayback Machine.

- ^[Do]quirus Doci f(ilius) / [Ce]lticoflavien(sis); Cassius Vegetus / Celti Flaviensis.

- ^Álvarez, Rosario, Francisco Dubert García, Xulio Sousa Fernández (ed.) (2006).Lingua e territorio(PDF).Santiago de Compostela: Consello da Cultura Galega. pp. 98–99.ISBN84-96530-20-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Indians were wont to use no bridles, like the Græcians and Celts. Edward Topsell,The historie of foure-footed beastes(1607), p. 251 (cited afterOED).

- ^(Lhuyd, p. 290) Lhuyd, E."Archaeologia Britannica; An account of the languages, histories, and customs of the original inhabitants of Great Britain."(reprint ed.) Irish University Press, 1971.ISBN0-7165-0031-0

- ^abLaing, Lloyd and Jenifer (1992)Art of the Celts,London, Thames and HudsonISBN0-500-20256-7

- ^Upton, Clive;Kretzschmar, William A. Jr. (2017).The Routledge Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English(2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 204.ISBN978-1-138-12566-7.

- ^Butterfield, J. (2015).Fowler's Dictionary of Modern English Usage(fourth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 142.

- ^OED,s.v. "Celt", "Celtic".

- ^Merriam-Webster,s.v. "Celt", "Celtic".

- ^Fowler, H.W. (1926).A Dictionary of Modern English Usage.Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 72.

- ^MacKillop, J. (1998)Dictionary of Celtic Mythology.New York: Oxford University PressISBN0-19-869157-2

- ^@theanglocelt Twitter feed

- ^(Lhuyd, p. 290) Lhuyd, E. (1971)Archaeologia Britannica; An account of the languages, histories, and customs of the original inhabitants of Great Britain.(reprint ed.) Irish University Press,ISBN0-7165-0031-0

- ^"The word Celt",The Celt: A weekly periodical of Irish national literature edited by a committee of the Celtic Union,pp. 287–288, 28 November 1857,retrieved11 November2010

- ^Schumacher, Stefan; Schulze-Thulin, Britta; aan de Wiel, Caroline (2004).Die keltischen Primärverben. Ein vergleichendes, etymologisches und morphologisches Lexikon(in German). Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Kulturen der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 325–326.ISBN3-85124-692-6.

- ^ Rix, Helmut;Kümmel, Martin; Zehnder, Thomas; Lipp, Reiner; Schirmer, Brigitte (2001).Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben.Die Wurzeln und ihre Primärstammbildungen(in German) (2nd, expanded and corrected ed.). Wiesbaden, Germany: Ludwig Reichert Verlag. p. 185.ISBN3-89500-219-4.

- ^"Reconstruction:Proto-Germanic/Walhaz - Wiktionary".23 September 2021.

- ^Sjögren, Albert, "Le nom de" Gaule ", in" Studia Neophilologica ", Vol. 11 (1938/39) pp. 210-214.

- ^Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology(OUP 1966), p. 391.

- ^Nouveau dictionnaire étymologique et historique(Larousse 1990), p. 336.

- ^Neilson, William A. (ed.) (1957).Webster's New International Dictionary of the English Language, second edition.G & C Merriam Co. p. 2903.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^Koch, John Thomas (2006).Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia.ABC-CLIO. p. 532.ISBN1-85109-440-7.

- ^Mountain, Harry (1998).The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume 1.uPublish.com.p. 252.ISBN1-58112-889-4.

- ^See John Koch, 'The Celtic Lands', inMedieval Arthurian Literature: A Guide to Recent Research,edited by Norris J Lacy, (Taylor & Francis) 1996:267. For a full discussion of the etymology of Gaulish*uolco-,see Xavier Delamarre,Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise(Editions Errance), 2001:274-6, and for examples of Gaulish*uolco-in various ancient personal Celtic names see Xavier DelamarreNoms des personnes celtiques(Editions Errance) 2007, p. 237.