Natolin, Warsaw

Natolin | |

|---|---|

Belgradzka Street in Natolin, in 2021. | |

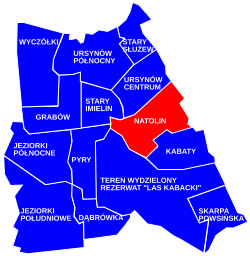

The location of the City Information System area of Natolin within the city district ofUrsynów | |

| Coordinates:52°08′23″N21°03′27″E/ 52.13972°N 21.05750°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Masovian |

| City and county | Warsaw |

| District | Ursynów |

| Time zone | UTC+1(CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2(CEST) |

| Area code | +48 22 |

Natolinis aneighbourhoodand aCity Information Systemarea located inWarsaw,Poland,within the district ofUrsynów.[1]It is a predominantly mid-rise multifamily residential area, with a smaller presence of low-rise single-family housing in the southwest.[2]

Most of its area consists of the mid-rise multifamily housing estates of Natolin andWyżyny.[3][4][5][6]In the southwest is also located the neighbourhood ofMoczydło,consisting of low-rise single-family housing.[7][2]The area also includes theNatolinstation of theM1line of theWarsaw Metrorapid transitunderground system.[8][9]Additionally, the neighbourhood is widely associated with theNatolin Park,that containsPotocki Palace.They are placed just outside its boundaries, within the district ofWilanów.[10]

By 1528, the small farming community of Moczydło was present in the area.[7]Between 1780 and 1783, the Potocki Palace, designed in theNeoclassicalstyle, was also constructed nearby. It became a residence of theCzartoryskiand, later,Potockifamilies.[11][12]The palace was rebuilt in its current form in 1838.[13]In 1879, a horsestablewas built in Moczydło, and the village became specialised in breeding horses for the local upper class. In the 1930s, it became a supplier for the newly opened, nearbySłużewiec Horse Racing Track,and remained as such untilSecond World War.[14][15]The area was incorporated into Warsaw in 1951.[16]Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the housing estates of Natolin and Wyżyny, consisting of multifamily residential buildings, were constructed in the neighborhood.[5][3]In 1995, the Natolin station of the Warsaw Metro opened.[8][9]

History

[edit]

By 1528, in the area was present the settlement ofMoczydło.It was a small farming community, located on the road leading toImielin,within theCatholicSt. Catherine Parish.The village was owned and inhabited by apetty nobility.Between 1580 and 1658, the village, and its adjusted farmlands, had an area of around 9 ha, and in 1661, there were 5 houses.[7][17][18]It was owned by Dąbrowski family until 1725, when it was sold together withWolicatoElżbieta Sieniawska,owner of theWilanów Estatefor the price of 60,000złoties.She has also ordered protection of the nearbyKabaty Woodsfromdeforestation.[19]

At the end of the 16th century, within the area of the current Natolin, kingJohn III Sobieskiestablished a designated royal area for animal hunting, as part of the nearbyWilanów Palacecomplex. In 1730, the estate owners,Maria Zofia CzartoryskaandAugust Aleksander Czartoryski,leased it to kingAugustus II the Strong,who turned it into thepheasantry.As such, the area became known asBażantaria(Polishforpheasantry). It was designed inFrench Baroquestyle, with paths braniching out away from the main building, similarly to those inPalace of Versailles.In 1733, the property was returned to its owners.[20][11]

In 1780, August Aleksander Czartoryski begun there the construction of his residence, which later would become known as thePotocki Palace.TheNeoclassicalpalace was designed by a renowned contemporary architectSzymon Bogumił Zugin the while the internal design was prepared byVincenzo Brenna.It featured a distinctive half-open salon, with a view on the forest below theWarsaw Escarpment.Its construction was finished in 1782, and following Czartoryski's death the same year, it was inherited by his daughter,Elżbieta Izabela Lubomirska.In 1799, it became a wedding gift to her daughterAleksandra Lubomirskaand brother-in-lawStanisław Kostka Potocki,and in 1805, it was inherited by their sonAleksander Stanisław Potockiand his wifeAnna Tyszkiewicz.In 1807, following the birth of their daughter,Natalia Potocka,the area was renamed after her toNatolin.[11][12][13]The palace was rebuilt in 1808 in accordance to project byChrystian Piotr Aigner,and again between 1834 and 1838, with project byEnrico Marconi.[12][13]In 1892, it was inherited by theBranicki family.[21]

In 1775, the village of Moczydło had 7 houses, and in 1785, 10 houses. In 1827, it had 10 houses and 80 inhabitants. Between 1850 and 1861, the population of Moczydło fought in court to lower costs of theirfeudal duties.Following theabolition of serfdomin 1864, the village was incorporated into themunicipalityofWilanów.At the time it was inhabited by 131 people and included 360 ha privately owned farmland, and 36 ha of nobility-owned farmland. In 1905, there were 20 houses and 146 inhabitants.[7]

In 1879, in Moczydło was built horsestable,owned by countLudwik Józef Krasiński,and the village became specialised in breeding horses for the local upper class. In the 1930s, it became a supplier for the newly opened nearbySłużewiec Horse Racing Track.It operated until the beginning of theSecond World War.[14][15]Following the end of the war, the farmlands of Moczydło were nationalised, and in 1956, they were donated by the state to theWarsaw University of Life Sciences.[15][22]The ruins of the stable survive to the present day, now with the status of a protectedcultural property.[14]

During the Second World War, whileWarsawwas under theGerman occupation,theNatolin Woodsnear the Potocki Palace became the sight of one of the firstwar crimescommitted by theNazi Germanyofficers in the city. Sometime between 13 and 17 November 1939, fifteenPolishmen were executed by shooting. The bodies were exhumed in 1971, and in 2022, the tragedy was commemorated with a small monument erected near the palace.[23][24]During theWarsaw Uprising,and following its end, the palace was devastated and plundered by German forces, together with other wealthy buildings in Natolin.[25]

In 1945, Potocki Palace was nationalised, and placed under the administration of theWarsaw National Museum.It was renovated and turned into the official residence of thePresident of Poland,Bolesław Bierut.Later it was used by theCouncil of Ministers Office.[25]In 1991, around 100 ha of theNatolin Parkreceived the status of thenature reserveof theNatolin Woods.[26]In 1992, the palace became the campus of the branch of theCollege of Europe.Around it were also built several other university buildings.[25]

On 14 May 1951, the area, including Natolin and Moczydło, was incorporated into the city of Warsaw.[16]

Beginning in 1981, throughout the 1980s, between Pileckiego,Stryjeńskich,and Przy Bażantarni Streets, and Komisji Edukacji Narodowej Avenue, was constructed the housing estate ofWyżyny,consisting oflarge panel systemmultifamily residential buildings.[5][6]Later, beginning in 1987, and continuing throughout the 1990s and 2000s, to the south and east were also constructed a series of housing estates ofmultifamily residentialbuildings, as part of the development of the neighbourhood of Natolin. It also partially encompassed the nearby neighbourhood ofKabaty.[3][4]Both developments were designed byJacek Jan Nowicki.[5][27]

In 1994, the neighbourhood became part of the then-established city district ofUrsynów.Natolin Park and Potocki Palace, historically associated with it, became part ofWilanówinstead.[28]In 1998, the district of was subdivided into the areas of theCity Information System,with Natolin becoming one of them.[1]

On 7 April 1995, there was opened theNatolinstation of theM1line of theWarsaw Metrorapid transitunderground syststem, placed at the intersection of Belgradzka Street and Komisji Edukacji Narodowej Avenue.[8][9]

Between 1992 and 2002, at 3 Przy Bażantarni Street, was constructed theCatholicBlessed Ladislas of Gielniów Church.[29]Between 1993 and 2003, at 21 Stryjeńskich Street, was also built the CatholicChurch of the Presentation of Jesus.[30]

Between 2002 and 2004, in the area of 13 Stryjeńskich Street, was constructed a housing estate ofVitaParc,consisting of five multifamily residential buildings.[31]

Throughout 2000s and 2010s, in the area were developed four urban parks. They were theMoczydełko Parkopened in 2009,Birch Woods Parkin 2010,Przy Bażantarni Parkbetween 2008 and 2013, andSilent Unseen Parkin 2016.[32][33][34][35]

Characteristics

[edit]

TheCity Information Systemarea of Natolin is dominated by mid-rise multifamily residential area.[2]Most of it consists of the housing estate of Natolin.[3][4]Between Pileckiego,Stryjeńskich,and Przy Bażantarni Streets, and Komisji Edukacji Narodowej Avenue is also located the housing estate ofWyżyny,and in the area of 13 Stryjeńskich Street, a small housing estate ofVitaParc.[5][6][31]In the southwest, to the west of Stryjeńskich Street, is also located the neighbourhood ofMoczydło,consisting predominantly of low-rise single-family housing.[7][2]At the intersection of Belgradzka Street and Komisji Edukacji Narodowej Avenue is placed theNatolinstation of theM1line of theWarsaw Metrorapid transitunderground system.[8][9]

In Natolin are present four urban parks. They are theBirch Woods Park,Moczydełko Park,Przy Bażantarni Park,andSilent Unseen Park.[34][36][37][38]Additionally, right outside its boundary, next to Nowoursynowska Street, is placed theNatolin Park,which includes the 19th-centuryPotocki Palacebuilt in theNeoclassical style,as well as theNatolin Woodsnature reserve with the area of around 100 ha.[10]In the eastern part of the neighbourhood are also located three small ponds, known asMoczydło 1,2and3.[39]Near Nowoursynowska Street also grows apedunculate oaknamedMieszko I,which with the age of around 600 years, is one of the oldest trees in Poland.[40]

Within the neighbourhood are also located twoCatholicchurches. They are theBlessed Ladislas of Gielniów Churchat 3 Przy Bażantarni Street, andChurch of the Presentation of Jesusat 21 Stryjeńskich Street.[29][30]

References

[edit]- ^ab"Obszary MSI. Dzielnica Ursynów".zdm.waw.pl(in Polish).

- ^abcdStudium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego miasta stołecznego Warszawy ze zmianami.Warsaw: Warsaw City Council, 1 March 2018, pp. 10–14. (in Polish)

- ^abcdLech Chmielewski:Przewodnik warszawski. Gawęda o nowej Warszawie.Warsaw: Agencja Omnipress, Państwowe Przedsiębiorstwo Wydawnicze Rzeczpospolita, 1987, p. 62. ISBN 83-85028-56-0. (in Polish)

- ^abcMaciej Mazur:Czasoprzewodnik. 33 lata na Ursynowie.Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Myśliński, 2010, p. 139–140. ISBN 978-83-915427-9-8. (in Polish)

- ^abcdeBarbara Petrozolin-Skowrońska (editor):Encyklopedia Warszawy.Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1994, p 920–921, ISBN 83-01-08836-2. (in Polish)

- ^abcTomasz Gamdzyk: "Przekształcenie osiedli", Sławomir Gzell (editor):Krajobraz architektoniczny Warszawy końca XX wieku.Warsaw: Towarzystwo Urbanistów Polskich, 2002, p. 209–227, ISBN 83-85892-39-7. (in Polish)

- ^abcdeBarbara Petrozolin-Skowrońska (editor):Encyklopedia Warszawy.Warsaw: Wydawnctwo Naukowe PWN, 1994, ISBN 83-01-08836-2. (in Polish)

- ^abcdWszystko zaczęło się na Wilanowskiej – 20 lat metra.In:iZTM,no. 4 (86). April 2015. Warsaw: Zarząd Transportu Miejskiego. p. 9-10. (in Polish)

- ^abcd"Dane techniczne i eksploatacyjne istniejącego odcinka metra".metro.waw.pl(in Polish).

- ^ab"Wilanowski Park Kulturowy – zespół pałacowo-parkowy Natolin".um.warszasa.pl(in Polish). 21 April 2021.

- ^abcWiesław Głębocki, Tadeusz Kobyłka:Pałace Warszawy.Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Sport i Turystyka, 1991, p. 86.ISBN9788321728148(in Polish)

- ^abcTadeusz Stefan Jaroszewski, Waldemar Baraniewski:Pałace i dwory w okolicach Warszawy.Warsaw:Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1992, p. 103–106.ISBN9788301109103.(in Polish)

- ^abcTadeusz Stefan Jaroszewski:The Book of Warsaw Palaces.Interpress Publishers, 1985, p. 80–120.ISBN9788322320488.

- ^abc"Folwark Moczydło – stajnia hrabiego Krasińskiego".um.warszawa.pl(in Polish). 26 March 2021.

- ^abcKamil Jabłczyński (11 January 2022)."Stajnia Folwarku Moczydło odzyska dawny blask. Kiedyś był tu słynny ośrodek jeździecki. Później niszczała przez lata".warszawa.naszemiasto.pl(in Polish).

- ^ab"Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 5 maja 1951 r. w sprawie zmiany granic miasta stołecznego Warszawy".isap.sejm.gov.pl(in Polish).

- ^Witold Małcużyński:Rozwój terytorjalny miasta Warszawy,Warsaw, 1900. (in Polish)

- ^Adolf Pawiński:Polska XVI wieku pod względem geograficzno-statystycznym,vol. 5:Mazowsze.Warsaw, 1895, p. 261. (in Polish)

- ^Janusz Nowak: "Dobra wilanowskie za Elżbiety Sieniawskiej 1720–1729 w świetle archiwaliów Biblioteki Czartoryskich w Krakowie",Studia Wilanowskie,no. 14. Warsaw, 2003, p. 53, ISSN 0137-7329. (in Polish)

- ^Małgorzata Szafrańska (editor):Królewskie ogrody w Polsce. Materiały sesji naukowej: Warszawa, 10-11 maja 2001 roku.Warsaw: Towarzystwo Opieki nad Zabytkami, 2001, p. 227.ISBN9788388372179.(in Polish)

- ^Karol Mórawski, Wiesław Głębocki:Warszawa. Mały przewodnik.Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1987, p. 132. (in Polish)

- ^"Historia".sggw.edu.pl(in Polish).

- ^Rafał Kuzak (2 November 2021)."'Kule podziurawiły go jak sito'. Relacje świadków niemieckiej zbrodni w Natolinie ".wielkahistoria.pl(in Polish).

- ^Wojciech Karpieszuk: "Puszcza obok blokowiska",Gazeta Stołeczna,8 September 2023, p. 9. Warsaw: Wyborcza. (in Polish)

- ^abc"Historia Natolina".natolin.edu.pl(in Polish).

- ^"Rezerwat przyrody Las Natoliński".crfop.gdos.gov.pl(in Polish).

- ^Lech Królikowski:Ursynów wczoraj, dziś, jutro.Warsaw, 2014, p. 212. (in Polish)

- ^"Ustawa z dnia 25 marca 1994 r. o ustroju miasta stołecznego Warszawy".isap.sejm.gov.pl(in Polish).

- ^ab"Warszawa. Bł. Władysława z Gielniowa".archwwa.pl(in Polish). 25 September 2023.

- ^ab"Warszawa. Ofiarowania Pańskiego".archwwa.pl(in Polish). 18 January 2024.

- ^abGrzegorz Stasiny, Olgierd Jagiełło: "Osiedle VitaParc",Architektura Murator,no. 6 (129). Warsaw, June 2005, p. 40–45, ISSN 1232-6372. (in Polish)

- ^"Kończymy budowę parku z oczkiem wodnym 'Moczydło 3'".archiwym.ursynow.pl(in Polish). 20 November 2009.

- ^Marta Siesicka-Osiak (24 January 2018)."Lasek Brzozowy. Miał być park 'cudo', skończy się na tym co jest".haloursynow.pl(in Polish).

- ^ab"Park Przy Bażantarni".ursynow.um.warszawa.pl(in Polish).

- ^"Uchwała nr XXVII/693/2016 Rady Miasta Stołecznego Warszawy z dnia 12 maja 2016 r. w sprawie utworzenia parku miejskiego na terenie Dzielnicy Ursynów m.st. Warszawy".edziennik.mazowieckie.pl(in Polish).

- ^"Park Moczydełko".ursynow.um.warszawa.pl(in Polish).

- ^"Park Lasek Brzozowy".ursynow.um.warszawa.pl(in Polish).

- ^"Park im. Cichociemnych Spadochroniarzy AK".ursynow.um.warszawa.pl(in Polish).

- ^Barbara Petrozolin-Skowrońska (editor):Encyklopedia Warszawy.Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1994, p. 968, ISBN 83-01-08836-2. (in Polish)

- ^Warszawska przyroda. Obszary i obiekty chronione.Warsaw: Biuro Ochrony Środowiska Urzędu m.st. Warszawy, 2005, p. 120. (in Polish)

External links

[edit] Media related toNatolinat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toNatolinat Wikimedia Commons