Neolithic

| |

| Period | Final period ofStone Age |

|---|---|

| Dates | c. 10,000 BC to c. 2,000 BC |

| Preceded by | Mesolithic,Epipalaeolithic |

| Followed by | Chalcolithic |

| Part ofa serieson |

| Human history andprehistory |

|---|

| ↑beforeHomo(Pliocene epoch) |

| ↓Future(Holocene epoch) |

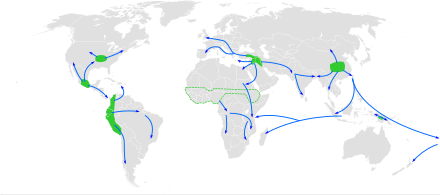

TheNeolithicorNew Stone Age(fromGreekνέοςnéos'new' andλίθοςlíthos'stone') is anarchaeological period,the final division of theStone AgeinEurope,AsiaandAfrica.It saw theNeolithic Revolution,a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts of the world. This "Neolithic package" included theintroduction of farming,domestication of animals,and change from ahunter-gathererlifestyle to one ofsettlement.The term 'Neolithic' was coined bySir John Lubbockin 1865 as a refinement of thethree-age system.[1]

The Neolithic began about 12,000 years ago when farming appeared in theEpipalaeolithic Near East,and later in other parts of the world. It lasted in theNear Eastuntil the transitional period of theChalcolithic(Copper Age) from about 6,500 years ago (4500 BC), marked by the development ofmetallurgy,leading up to theBronze AgeandIron Age.

In other places, the Neolithic followed theMesolithic(Middle Stone Age) and then lasted until later. InAncient Egypt,the Neolithic lasted until theProtodynastic period,c.3150 BC.[2][3][4]InChina,it lasted until circa 2000 BC with the rise of thepre-ShangErlitou culture,[5]as it did inScandinavia.[6][7][8]

Origin[edit]

Following theASPRO chronology,the Neolithic started in around 10,200 BC in theLevant,arising from theNatufian culture,when pioneering use of wildcerealsevolved into earlyfarming.The Natufian period or "proto-Neolithic" lasted from 12,500 to 9,500 BC, and is taken to overlap with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPNA) of 10,200–8800 BC. As the Natufians had become dependent on wild cereals in their diet, and asedentaryway of life had begun among them, the climatic changes associated with theYounger Dryas(about 10,000 BC) are thought to have forced people to develop farming.

Early Neolithic farming was limited to a narrow range of plants, both wild and domesticated, which includedeinkorn wheat,milletandspelt,and the keeping ofdogs.By about 8000 BC, it included domesticatedsheepandgoats,cattleandpigs.

Not all of these cultural elements characteristic of the Neolithic appeared everywhere in the same order: the earliest farming societies in theNear Eastdid not use pottery. In other parts of the world, such asAfrica,South AsiaandSoutheast Asia,independent domestication events led to their own regionally distinctive Neolithic cultures, which arose completely independently of those inEuropeandSouthwest Asia.Early Japanesesocieties and otherEast Asiancultures used potterybeforedeveloping agriculture.[10][11]

Periods by region[edit]

Southwest Asia[edit]

This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(August 2015) |

Prehistoric Southwest Asia | ||

4000 — – 5000 — – 6000 — – 7000 — – 8000 — – 9000 — – 10000 — – 11000 — – 12000 — – 13000 — – 14000 — – 15000 — – 16000 — – 17000 — – 18000 — – 19000 — – 20000 — – 21000 — – 22000 — – 23000 — – 24000 — – 25000 — – 26000 — | ↓Historic↓ | |

Axis scale is yearsBefore Present | ||

In theMiddle East,cultures identified as Neolithic began appearing in the 10thmillenniumBC.[12]Early development occurred in theLevant(e.g.Pre-Pottery Neolithic AandPre-Pottery Neolithic B) and from there spread eastwards and westwards. Neolithic cultures are also attested in southeasternAnatoliaand northern Mesopotamia by around 8000 BC.[citation needed]

Anatolian Neolithic farmersderived a significant portion of their ancestry from theAnatolian hunter-gatherers(AHG), suggesting that agriculture was adopted in site by these hunter-gatherers and not spread bydemic diffusioninto the region.[13]

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A[edit]

The Neolithic 1 (PPNA) period began roughly around 10,000 BC in theLevant.[12]A temple area in southeastern Turkey atGöbekli Tepe,dated to around 9500 BC, may be regarded as the beginning of the period. This site was developed by nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes, as evidenced by the lack of permanent housing in the vicinity, and may be the oldest known human-made place of worship.[17]At least seven stone circles, covering 25 acres (10 ha), contain limestone pillars carved with animals, insects, and birds. Stone tools were used by perhaps as many as hundreds of people to create the pillars, which might have supported roofs. Other early PPNA sites dating to around 9500–9000 BC have been found inTell es-Sultan(ancient Jericho),Israel(notablyAin Mallaha,Nahal Oren,andKfar HaHoresh),Gilgalin theJordan Valley,andByblos,Lebanon.The start of Neolithic 1 overlaps theTahunianandHeavy Neolithicperiods to some degree.[citation needed]

The major advance of Neolithic 1 was true farming. In the proto-NeolithicNatufiancultures, wild cereals were harvested, and perhaps early seed selection and re-seeding occurred. The grain was ground into flour.Emmer wheatwas domesticated, and animals were herded and domesticated (animal husbandryandselective breeding).[citation needed]

In 2006, remains offigswere discovered in a house in Jericho dated to 9400 BC. The figs are of a mutant variety that cannot be pollinated by insects, and therefore the trees can only reproduce from cuttings. This evidence suggests that figs were the first cultivated crop and mark the invention of the technology of farming. This occurred centuries before the first cultivation of grains.[18]

Settlements became more permanent, with circular houses, much like those of the Natufians, with single rooms. However, these houses were for the first time made ofmudbrick.The settlement had a surrounding stone wall and perhaps a stone tower (as in Jericho). The wall served as protection from nearby groups, as protection from floods, or to keep animals penned. Some of the enclosures also suggest grain and meat storage.[19]

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B[edit]

The Neolithic 2 (PPNB) began around 8800 BC according to theASPRO chronologyin the Levant (Jericho,West Bank).[12]As with the PPNA dates, there are two versions from the same laboratories noted above. This system of terminology, however, is not convenient for southeastAnatoliaand settlements of the middle Anatolia basin.[citation needed]A settlement of 3,000 inhabitants called'Ain Ghazalwas found in the outskirts ofAmman,Jordan.Considered to be one of the largest prehistoric settlements in theNear East,it was continuously inhabited from approximately 7250 BC to approximately 5000 BC.[20]

Settlements have rectangular mud-brick houses where the family lived together in single or multiple rooms. Burial findings suggest anancestor cultwhere peoplepreserved skullsof the dead, which were plastered with mud to make facial features. The rest of the corpse could have been left outside the settlement to decay until only the bones were left, then the bones were buried inside the settlement underneath the floor or between houses.[citation needed]

Pre-Pottery Neolithic C[edit]

Work at the site of'Ain GhazalinJordanhas indicated a laterPre-Pottery Neolithic Cperiod.Juris Zarinshas proposed that a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex developed in the period from the climatic crisis of 6200 BC, partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon domesticated animals, and a fusion withHarifianhunter gatherers in the Southern Levant, with affiliate connections with the cultures ofFayyumand theEastern DesertofEgypt.Cultures practicing this lifestyle spread down theRed Seashoreline and moved east fromSyriainto southernIraq.[21]

Late Neolithic[edit]

The Late Neolithic began around 6,400 BC in theFertile Crescent.[12]By then distinctive cultures emerged, with pottery like theHalafian(Turkey, Syria, Northern Mesopotamia) andUbaid(Southern Mesopotamia). This period has been further divided intoPNA(Pottery Neolithic A) andPNB(Pottery Neolithic B) at some sites.[22]

The Chalcolithic (Stone-Bronze) period began about 4500 BC, then theBronze Agebegan about 3500 BC, replacing the Neolithic cultures.[citation needed]

Fertile Crescent[edit]

Around 10,000 BC the first fully developed Neolithic cultures belonging to the phasePre-Pottery Neolithic A(PPNA) appeared in the Fertile Crescent.[12]Around 10,700–9400 BC a settlement was established inTell Qaramel,10 miles (16 km) north ofAleppo.The settlement included two temples dating to 9650 BC.[23]Around 9000 BC during the PPNA, one of the world's first towns,Jericho,appeared in the Levant. It was surrounded by a stone wall, may have contained a population of up to 2,000–3,000 people, and contained a massive stone tower.[24]Around 6400 BC theHalaf cultureappeared in Syria and Northern Mesopotamia.

In 1981, a team of researchers from theMaison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée,includingJacques Cauvinand Oliver Aurenche, divided Near East Neolithic chronology into ten periods (0 to 9) based on social, economic and cultural characteristics.[25]In 2002,Danielle StordeurandFrédéric Abbèsadvanced this system with a division into five periods.

- Natufianbetween 12,000 and 10,200 BC,

- Khiamianbetween 10,200 and 8800 BC,PPNA:Sultanian(Jericho),Mureybetian,

- Early PPNB (PPNB ancien) between 8800 and 7600 BC, middle PPNB (PPNB moyen) between 7600 and 6900 BC,

- Late PPNB (PPNB récent) between 7500 and 7000 BC,

- A PPNB (sometimes called PPNC) transitional stage (PPNB final) in which Halaf anddark faced burnished warebegin to emerge between 6900 and 6400 BC.[26]

They also advanced the idea of a transitional stage between the PPNA and PPNB between 8800 and 8600 BC at sites likeJerf el AhmarandTell Aswad.[27]

Southern Mesopotamia[edit]

Alluvial plains (Sumer/Elam). Low rainfall makesirrigationsystems necessary.Ubaidculture from 6,900 BC.[citation needed]

Northeastern Africa[edit]

The earliest evidence of Neolithic culture in northeast Africa was found in the archaeological sites ofBir KiseibaandNabta Playain what is now southwest Egypt.[28]Domestication ofsheepandgoatsreachedEgyptfrom theNear Eastpossibly as early as 6000 BC.[29][30][31]Graeme Barkerstates "The first indisputable evidence for domestic plants and animals in the Nile valley is not until the early fifth millennium BC in northern Egypt and a thousand years later further south, in both cases as part of strategies that still relied heavily on fishing, hunting, and the gathering of wild plants" and suggests that these subsistence changes were not due to farmers migrating from the Near East but was an indigenous development, with cereals either indigenous or obtained through exchange.[32]Other scholars argue that the primary stimulus for agriculture and domesticated animals (as well as mud-brick architecture and other Neolithic cultural features) in Egypt was from the Middle East.[33][34][35]

Northwestern Africa[edit]

The neolithization ofNorthwestern Africawas initiated byIberian,Levantine(and perhapsSicilian) migrants around 5500-5300 BC.[36]During the Early Neolithic period, farming was introduced by Europeans and was subsequently adopted by the locals.[36]During the Middle Neolithic period, an influx of ancestry from the Levant appeared in Northwestern Africa, coinciding with the arrival ofpastoralismin the region.[36]The earliest evidence for pottery, domestic cereals andanimal husbandryis found in Morocco, specifically atKaf el-Ghar.[36]

Sub-Saharan Africa[edit]

ThePastoral Neolithicwas a period in Africa'sprehistorymarking the beginning of food production on the continent following theLater Stone Age.In contrast to the Neolithic in other parts of the world, which saw the development offarmingsocieties, the first form of African food production was mobilepastoralism,[37][38]or ways of life centered on the herding and management of livestock. The term "Pastoral Neolithic" is used most often byarchaeologiststo describe early pastoralist periods in theSahara,[39]as well as ineastern Africa.[40]

TheSavanna Pastoral Neolithicor SPN (formerly known as theStone Bowl Culture) is a collection of ancient societies that appeared in theRift ValleyofEast Africaand surrounding areas during a time period known as thePastoral Neolithic.They wereSouth Cushiticspeaking pastoralists, who tended to bury their dead in cairns whilst their toolkit was characterized by stone bowls, pestles, grindstones and earthenware pots.[41]Through archaeology, historical linguistics and archaeogenetics, they conventionally have been identified with the area's firstAfroasiatic-speaking settlers. Archaeological dating of livestock bones and burial cairns has also established the cultural complex as the earliest center ofpastoralismand stone construction in the region.[42]

Europe[edit]

In southeastEuropeagrarian societies first appeared in the7th millennium BC,attested by one of the earliest farming sites of Europe, discovered inVashtëmi,southeasternAlbaniaand dating back to 6500 BC.[43][44]In most of Western Europe in followed over the next two thousand years, but in some parts of Northwest Europe it is much later, lasting just under 3,000 years from c. 4500 BC–1700 BC. Recent advances inarchaeogeneticshave confirmed that the spread of agriculture from the Middle East to Europe was strongly correlated with the migration ofearly farmers from Anatoliaabout 9,000 years ago, and was not just a cultural exchange.[45][46]

Anthropomorphic figurines have been found in the Balkans from 6000 BC,[47]and in Central Europe by around 5800 BC (La Hoguette). Among the earliest cultural complexes of this area are theSeskloculture in Thessaly, which later expanded in the Balkans giving rise toStarčevo-Körös(Cris),Linearbandkeramik,andVinča.Through a combination ofcultural diffusionandmigration of peoples,the Neolithic traditions spread west and northwards to reach northwestern Europe by around 4500 BC. TheVinča culturemay have created the earliest system of writing, theVinča signs,though archaeologist Shan Winn believes they most likely representedpictogramsandideogramsrather than a truly developed form of writing.[48]

TheCucuteni-Trypillian culturebuilt enormous settlements in Romania, Moldova and Ukraine from 5300 to 2300 BC. Themegalithictemple complexes ofĠgantijaon the Mediterranean island ofGozo(in the Maltese archipelago) and ofMnajdra(Malta) are notable for their gigantic Neolithic structures, the oldest of which date back to around 3600 BC. TheHypogeum of Ħal-Saflieni,Paola,Malta, is a subterranean structure excavated around 2500 BC; originally a sanctuary, it became anecropolis,the only prehistoric underground temple in the world, and shows a degree of artistry in stone sculpture unique in prehistory to the Maltese islands. After 2500 BC, these islands were depopulated for several decades until the arrival of a new influx ofBronze Ageimmigrants, a culture thatcrematedits dead and introduced smaller megalithic structures calleddolmensto Malta.[49]In most cases there are small chambers here, with the cover made of a large slab placed on upright stones. They are claimed to belong to a population different from that which built the previous megalithic temples. It is presumed the population arrived fromSicilybecause of the similarity of Maltese dolmens to some small constructions found there.[50]

With some exceptions, population levels rose rapidly at the beginning of the Neolithic until they reached thecarrying capacity.[51]This was followed by a population crash of "enormous magnitude" after 5000 BC, with levels remaining low during the next 1,500 years.[51]Populations began to rise after 3500 BC, with further dips and rises occurring between 3000 and 2500 BC but varying in date between regions.[51]Around this time is theNeolithic decline,when populations collapsed across most of Europe, possibly caused by climatic conditions, plague, or mass migration.[52]

South and East Asia[edit]

Settled life, encompassing the transition from foraging to farming and pastoralism, began in South Asia in the region ofBalochistan,Pakistan, around 7,000 BC.[53][54][55]At the site ofMehrgarh,Balochistan, presence can be documented of the domestication of wheat and barley, rapidly followed by that of goats, sheep, and cattle.[56]In April 2006, it was announced in the scientific journalNaturethat the oldest (and firstEarly Neolithic) evidence for the drilling of teethin vivo(usingbow drillsandflinttips) was found in Mehrgarh.[57]

In South India, the Neolithic began by 6500 BC and lasted until around 1400 BC when the Megalithic transition period began. South Indian Neolithic is characterized by Ash mounds[clarification needed]from 2500 BC inKarnatakaregion, expanded later toTamil Nadu.[58]

In East Asia, the earliest sites include theNanzhuangtouculture around 9500–9000 BC,[59]Pengtoushan culturearound 7500–6100 BC, andPeiligang culturearound 7000–5000 BC. Theprehistoric Beifudi sitenearYixianin Hebei Province, China, contains relics of a culture contemporaneous with theCishanandXinglongwacultures of about 6000–5000 BC, Neolithic cultures east of theTaihang Mountains,filling in an archaeological gap between the two Northern Chinese cultures. The total excavated area is more than 1,200 square yards (1,000 m2;0.10 ha), and the collection of Neolithic findings at the site encompasses two phases.[60]Between 3000 and 1900 BC, theLongshan cultureexisted in the middle and lowerYellow Rivervalley areas of northern China. Towards the end of the 3rd millennium BC, the population decreased sharply in most of the region and many of the larger centres were abandoned, possibly due to environmental change linked to the end of theHolocene Climatic Optimum.[61]

The 'Neolithic' (defined in this paragraph as using polished stone implements) remains a living tradition in small and extremely remote and inaccessible pockets ofWest Papua.Polished stoneadzeand axes are used in the present day (as of 2008[update]) in areas where the availability of metal implements is limited. This is likely to cease altogether in the next few years as the older generation die off and steel blades and chainsaws prevail.[citation needed]

In 2012, news was released about a new farming site discovered inMunam-ri,Goseong,Gangwon Province,South Korea,which may be the earliest farmland known to date in east Asia.[62]"No remains of an agricultural field from the Neolithic period have been found in any East Asian country before, the institute said, adding that the discovery reveals that the history of agricultural cultivation at least began during the period on theKorean Peninsula".The farm was dated between 3600 and 3000 BC. Pottery, stone projectile points, and possible houses were also found." In 2002, researchers discovered prehistoricearthenware,jadeearrings, among other items in the area ". The research team will performaccelerator mass spectrometry(AMS) dating to retrieve a more precise date for the site.[63]

The Americas[edit]

InMesoamerica,a similar set of events (i.e., crop domestication and sedentary lifestyles) occurred by around 4500 BC in South America, but possibly as early as 11,000–10,000 BC. These cultures are usually not referred to as belonging to the Neolithic; in Americadifferent termsare used such asFormative stageinstead of mid-late Neolithic,Archaic Erainstead of Early Neolithic, andPaleo-Indianfor the preceding period.[64]

The Formative stage is equivalent to the Neolithic Revolution period in Europe, Asia, and Africa. In the southwestern United States it occurred from 500 to 1200 AD when there was a dramatic increase in population and development of large villages supported by agriculture based ondryland farmingof maize, and later, beans, squash, and domesticated turkeys. During this period the bow and arrow and ceramic pottery were also introduced.[65]In later periods cities of considerable size developed, and some metallurgy by 700 BC.[66]

Australia[edit]

Australia, in contrast toNew Guinea,has generally been held not to have had a Neolithic period, with ahunter-gathererlifestyle continuing until the arrival of Europeans. This view can be challenged in terms of the definition of agriculture, but "Neolithic" remains a rarely used and not very useful concept in discussingAustralian prehistory.[67]

Cultural characteristics[edit]

Social organization[edit]

During most of the Neolithic age ofEurasia,people lived in smalltribescomposed of multiple bands or lineages.[68]There is littlescientific evidenceof developedsocial stratificationin most Neolithic societies; social stratification is more associated with the laterBronze Age.[69]Although some late Eurasian Neolithic societies formed complex stratified chiefdoms or evenstates,generally states evolved in Eurasia only with the rise of metallurgy, and most Neolithic societies on the whole were relatively simple and egalitarian.[68]Beyond Eurasia, however, states were formed during the local Neolithic in three areas, namely in thePreceramic Andeswith theNorte Chico Civilization,[70][71]Formative MesoamericaandAncient Hawaiʻi.[72]However, most Neolithic societies were noticeably more hierarchical than theUpper Paleolithiccultures that preceded them and hunter-gatherer cultures in general.[73][74]

Thedomesticationoflarge animals(c. 8000 BC) resulted in a dramatic increase in social inequality in most of the areas where it occurred;New Guineabeing a notable exception.[75]Possession of livestock allowed competition between households and resulted in inherited inequalities of wealth. Neolithic pastoralists who controlled large herds gradually acquired more livestock, and this made economic inequalities more pronounced.[76]However, evidence of social inequality is still disputed, as settlements such asÇatalhöyükreveal a lack of difference in the size of homes and burial sites, suggesting a more egalitarian society with no evidence of the concept of capital, although some homes do appear slightly larger or more elaborately decorated than others.[citation needed]

Families and households were still largely independent economically, and the household was probably the center of life.[77][78]However, excavations inCentral Europehave revealed that early NeolithicLinear Ceramic cultures( "Linearbandkeramik") were building large arrangements ofcircular ditchesbetween 4800 and 4600 BC. These structures (and their later counterparts such ascausewayed enclosures,burial mounds,andhenge) required considerable time and labour to construct, which suggests that some influential individuals were able to organise and direct human labour – though non-hierarchical and voluntary work remain possibilities.

There is a large body of evidence for fortified settlements atLinearbandkeramiksites along theRhine,as at least some villages were fortified for some time with apalisadeand an outer ditch.[79][80]Settlements with palisades and weapon-traumatized bones, such as those found at theTalheim Death Pit,have been discovered and demonstrate that "...systematic violence between groups" and warfare was probably much more common during the Neolithic than in the preceding Paleolithic period.[74]This supplanted an earlier view of the Linear Pottery Culture as living a "peaceful, unfortified lifestyle".[81]

Control of labour and inter-group conflict is characteristic oftribalgroups withsocial rankthat are headed by a charismatic individual – either a 'big man' or a proto-chief– functioning as a lineage-group head. Whether a non-hierarchical system of organization existed is debatable, and there is no evidence that explicitly suggests that Neolithic societies functioned under any dominating class or individual, as was the case in thechiefdomsof the EuropeanEarly Bronze Age.[82]Possible exceptions to this include Iraq during theUbaid periodand England beginning in the Early Neolithic (4100–3000 BC).[83][84]Theories to explain the apparent implied egalitarianism of Neolithic (and Paleolithic) societies have arisen, notably theMarxistconcept ofprimitive communism.

Shelter and sedentism[edit]

The shelter of early people changed dramatically from theUpper Paleolithicto the Neolithic era. In the Paleolithic, people did not normally live in permanent constructions. In the Neolithic, mud brick houses started appearing that were coated with plaster.[85]The growth of agriculture made permanent houses far more common. AtÇatalhöyük9,000 years ago, doorways were made on the roof, with ladders positioned both on the inside and outside of the houses.[85]Stilt-housesettlements were common in theAlpineandPianura Padana(Terramare) region.[86]Remains have been found in theLjubljana MarshinSloveniaand at theMondseeandAtterseelakes inUpper Austria,for example.

Agriculture[edit]

A significant and far-reaching shift in humansubsistenceand lifestyle was to be brought about in areas where cropfarmingand cultivation were first developed: the previous reliance on an essentiallynomadichunter-gatherersubsistence techniqueorpastoral transhumancewas at first supplemented, and then increasingly replaced by, a reliance upon the foods produced from cultivated lands. These developments are also believed to have greatly encouraged the growth of settlements, since it may be supposed that the increased need to spend more time and labor in tending crop fields required more localized dwellings. This trend would continue into the Bronze Age, eventually giving rise to permanently settled farmingtowns,and latercitiesandstateswhose larger populations could be sustained by the increased productivity from cultivated lands.

The profound differences in human interactions and subsistence methods associated with the onset of early agricultural practices in the Neolithic have been called theNeolithic Revolution,a termcoinedin the 1920s by the Australian archaeologistVere Gordon Childe.

One potential benefit of the development and increasing sophistication of farming technology was the possibility of producing surplus crop yields, in other words, food supplies in excess of the immediate needs of the community. Surpluses could be stored for later use, or possibly traded for other necessities or luxuries. Agricultural life afforded securities that nomadic life could not, and sedentary farming populations grew faster than nomadic.

However, early farmers were also adversely affected in times offamine,such as may be caused bydroughtorpests.In instances where agriculture had become the predominant way of life, the sensitivity to these shortages could be particularly acute, affecting agrarian populations to an extent that otherwise may not have been routinely experienced by prior hunter-gatherer communities.[76]Nevertheless, agrarian communities generally proved successful, and their growth and the expansion of territory under cultivation continued.

Another significant change undergone by many of these newly agrarian communities was one ofdiet.Pre-agrarian diets varied by region, season, available local plant and animal resources and degree of pastoralism and hunting. Post-agrarian diet was restricted to a limited package of successfully cultivated cereal grains, plants and to a variable extent domesticated animals and animal products. Supplementation of diet by hunting and gathering was to variable degrees precluded by the increase in population above the carrying capacity of the land and a high sedentary local population concentration. In some cultures, there would have been a significant shift toward increased starch and plant protein. The relative nutritional benefits and drawbacks of these dietary changes and their overall impact on early societal development are still debated.

In addition, increased population density, decreased population mobility, increased continuous proximity to domesticated animals, and continuous occupation of comparatively population-dense sites would have alteredsanitationneeds and patterns ofdisease.

Lithic technology[edit]

The identifying characteristic of Neolithic technology is the use of polished or ground stone tools, in contrast to the flaked stone tools used during the Paleolithic era.

Neolithic people were skilled farmers, manufacturing a range of tools necessary for the tending, harvesting and processing of crops (such assickleblades andgrinding stones) and food production (e.g.pottery,bone implements). They were also skilled manufacturers of a range of other types of stone tools and ornaments, includingprojectile points,beads,andstatuettes.But what allowed forest clearance on a large scale was the polishedstone axeabove all other tools. Together with theadze,fashioning wood for shelter, structures andcanoesfor example, this enabled them to exploit the newly developed farmland.

Neolithic peoples in the Levant, Anatolia, Syria, northern Mesopotamia andCentral Asiawere also accomplished builders, utilizing mud-brick to construct houses and villages. AtÇatalhöyük,houses wereplasteredand painted with elaborate scenes of humans and animals. InEurope,long housesbuilt fromwattle and daubwere constructed. Elaboratetombswere built for the dead. These tombs are particularly numerous inIreland,where there are many thousand still in existence. Neolithic people in theBritish Islesbuiltlong barrowsandchamber tombsfor their dead andcausewayed camps,henges, flint mines andcursusmonuments. It was also important to figure out ways of preserving food for future months, such as fashioning relatively airtight containers, and using substances likesaltas preservatives.

The peoples of theAmericasand thePacificmostly retained the Neolithic level of tooltechnologyuntil the time of European contact. Exceptions include copperhatchetsandspearheadsin theGreat Lakesregion.

Clothing[edit]

Most clothing appears to have been made of animal skins, as indicated by finds of large numbers of bone and antler pins that are ideal for fastening leather.Woolcloth andlinenmight have become available during the later Neolithic,[87][88]as suggested by finds of perforated stones that (depending on size) may have served asspindle whorlsorloomweights.[89][90][91]

List of early settlements[edit]

| TheStone Age |

|---|

| ↑beforeHomo(Pliocene) |

|

| ↓Chalcolithic |

Neolithichuman settlementsinclude:

| name | location | early date (BC) | late date (BC) | comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tell Qaramel | Syria | 10,700[92] | 9400 | |

| Franchthi Cave | Greece | 10,000 | reoccupied between 7500 and 6000 BC | |

| Göbekli Tepe | Turkey | 9600 | 8000 | |

| Nanzhuangtou | Hebei,China | 9500 | 9000 | |

| Byblos | Lebanon | 8800 | 7000[93] | |

| Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) | West Bank | 9500 | arising from the earlierEpipaleolithicNatufian culture | |

| Pulli settlement | Estonia | 8500 | 5000 | oldest known settlement ofKunda culture |

| Aşıklı Höyük | Central Anatolia,Turkey,an Aceramic Neolithic period settlement | 8200 | 7400 | correlating with the E/MPPNB in the Levant |

| Nevali Cori | Turkey | 8000 | ||

| Bhirrana | India | 7600 | 7200 | Hakra ware |

| Pengtoushan culture | China | 7500 | 6100 | rice residues were carbon-14 dated to 8200–7800 BC |

| Çatalhöyük | Turkey | 7500 | 5700 | |

| Mentesh Tepe and Kamiltepe | Azerbaijan | 7000 | 3000[94] | |

| 'Ain Ghazal | Jordan | 7250 | 5000 | |

| Chogha Bonut | Iran | 7200 | ||

| Jhusi | India | 7100 | ||

| Motza | Israel | 7000 | ||

| Ganj Dareh | Iran | 7000 | ||

| Lahuradewa | India | 7000[95] | presence of rice cultivation, ceramics etc. | |

| Jiahu | China | 7000 | 5800 | |

| Knossos | Crete | 7000 | ||

| Khirokitia | Cyprus | 7000 | 4000 | |

| Mehrgarh | Pakistan | 7000 | 5500 | aceramic but elaborate culture including mud brick, houses, agriculture etc. |

| Sesklo | Greece | 6850 | with a 660-year margin of error | |

| Horton Plains | Sri Lanka | 6700 | cultivation of oats and barley as early as 11,000 BC | |

| Porodin | North Macedonia | 6500[96] | ||

| Padah-Lin Caves | Burma | 6000 | ||

| Petnica | Serbia | 6000 | ||

| Stara Zagora | Bulgaria | 5500 | ||

| Cucuteni-Trypillian culture | Ukraine,MoldovaandRomania | 5500 | 2750 | |

| Tell Zeidan | northern Syria | 5500 | 4000 | |

| Tabon CaveComplex | Quezon, Palawan,Philippines | 5000 | 2000[97][98] | |

| Hemudu culture,large-scale rice plantation | China | 5000 | 4500 | |

| TheMegalithic Temples of Malta | Malta | 3600 | ||

| Knap of HowarandSkara Brae | Orkney,Scotland | 3500 | 3100 | |

| Brú na Bóinne | Ireland | 3500 | ||

| Lough Gur | Ireland | 3000 | ||

| Shengavit Settlement | Armenia | 3000 | 2200 | |

| Norte Chico civilization,30 aceramic Neolithic period settlements | northern coastalPeru | 3000 | 1700 | |

| TichitNeolithic village on theTagant Plateau | central southernMauritania | 2000 | 500 | |

| Oaxaca,state | Southwestern Mexico | 2000 | by 2000 BC Neolithic sedentary villages had been established in the Central Valleys region of this state. | |

| Lajia | China | 2000 | ||

| Mumun pottery period | Korean Peninsula | 1800 | 1500 | |

| Neolithic revolution | Japan | 500 | 300 |

The world's oldest known engineeredroadway,thePost TrackinEngland,dates from 3838 BC and the world's oldest freestanding structure is the Neolithic temple ofĠgantijainGozo,Malta.

List of cultures and sites[edit]

| TheNeolithic |

|---|

| ↑Mesolithic |

| ↓Chalcolithic |

Note: Dates are very approximate, and are only given for a rough estimate; consult each culture for specific time periods.

Early Neolithic

Periodization:The Levant:9500–8000 BC;Europe:7000–4000 BC; Elsewhere: varies greatly, depending on region.

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic A(Levant, 9500–8000 BC)

- Nanzhuangtou(China, 8500 BC)

- Franchthi Cave(Greece, 7000 BC)

- Cishan culture(China, 6500–5000 BC)

- Sesklovillage (Greece, c. 6300 BC)

- Starcevo-Criş culture (Starčevo-Körös-Criş culture)(Balkans, 5800–4500 BC)

- Katundas Cavern(Albania, 6th millennium BC)

- Dudeşti culture(Romania, 6th millennium BC)

- Beixin culture(China, 5300–4100 BC)

- Tamil Nadu culture(India, 3000–2800 BC)[99]

- Mentesh Tepe and Kamiltepe (Azerbaijan, 7000–3000 BC)[94]

Middle Neolithic

Periodization:The Levant:8000–6500 BC;Europe:5500–3500 BC; Elsewhere: varies greatly, depending on region.

- Pre-Pottery Neolithic B(Levant, 7600–6000 BC)

- Baodun culture

- Jinsha settlementandSanxingduimound.

- Çatalhöyük

- Cardium potteryculture

- Comb Ceramic culture

- Corded Wareculture

- Cortaillod culture

- Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

- Dadiwan culture

- Dawenkou culture

- Daxi culture

- Chengtoushansettlement

- Dapenkeng culture(Taiwan, 4000–3000 BC)

- Grooved ware people

- Skara Brae,et al.

- Erlitou culture

- Ertebølle culture

- Hemburyculture

- Hemudu culture

- Hongshan culture

- Houli culture

- Horgenculture

- Kura–Araxes culture

- Liangzhu culture

- Linear Pottery culture

- Goseck circle,Circular ditches,et al.

- Longshan culture

- Majiabang culture

- Majiayao culture

- Peiligang culture

- Pengtoushan culture

- Pfyn culture

- Precucuteni culture

- Qujialing culture

- Shijiahe culture

- Trypillian culture

- Vinča culture

- Lengyel culture(Central Europe, 5000–3400 BC)

- Varna culture(South/Eastern Europe 4400–4100 BC)

- Windmill Hill culture

- Xinglongwa culture

- Beifudisite

- Xinle culture

- Yangshao culture

- Zhaobaogou culture

Later Neolithic

Periodization:6500–4500 BC;Europe:5000–3000 BC; Elsewhere: varies greatly, depending on region.

- Pottery Neolithic(Fertile Crescent, 6400–4500 BC)

- Halaf culture(Mesopotamia, 6100 BC and 5100 BC)

- Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period(Mesopotamia, 5500–5000 BC)

- Ubaid 1/2(5400–4500 BC)

- Funnelbeaker culture(North/Eastern Europe, 4300–2800 BC)

- Chalcolithic

Periodization:Near East:6000–3500 BC;Europe:5000–2000 BC;Elsewhere:varies greatly, depending on region. In the Americas, the Chalcolithic ended as late as the 19th century AD for some peoples.

- Ubaid 3/4(Mesopotamia, 4500–4000 BC)

- early Uruk period(Mesopotamia, 4000–3800 BC)

- middle Uruk period(Mesopotamia, 3800–3400 BC)

- late Trypillian(Eastern Europe, 3000–2750 BC)

- Gaudo Culture(Italy, 3150–2950 BC)

- Corded Ware culture(North/Eastern Europe, 2900–2350 BC)

- Beaker culture(Central/Western Europe, 2900–1800 BC)

Comparative chronology[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^"Neolithic".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^Karin Sowada and Peter Grave. Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Old Kingdom.

- ^Lukas de Blois and R. J. van der Spek.An Introduction to the Ancient World.p. 14.

- ^"Neolithic Periods Overview".egyptianmuseum.org.Retrieved2022-04-20.

- ^Chang, K.C.: "Studies of Shang Archaeology", pp. 6–7, 1. Yale University Press, 1982.

- ^Encyclopedia Britannica, "Stone Age"

- ^Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Piazza, Alberto (1994).The History and Geography of Human Genes.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 351.

at first European contact.... [New Guineans] represented... modern examples of Neolithic horticulturalists

- ^Hampton, O. W. (1999).Culture of Stone: Sacred and Profane Uses of Stone Among the Dani.College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. p. 6.

- ^Diamond, J.;Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions".Science.300(5619): 597–603.Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D.CiteSeerX10.1.1.1013.4523.doi:10.1126/science.1078208.PMID12714734.S2CID13350469.

- ^Habu, Junko (2004).Ancient Jomon of Japan.Cambridge University Press. p. 3.ISBN978-0-521-77670-7.

- ^ Xiaohong Wu (2012)."Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China".Science.336(6089). Sciencemag.org: 1696–1700.Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W.doi:10.1126/science.1218643.PMID22745428.S2CID37666548.Retrieved15 January2015.

- ^abcdeBellwood 2004,p. 384.

- ^Krause, Johannes; Jeong, Choongwon; Haak, Wolfgang; Posth, Cosimo; Stockhammer, Philipp W.; Mustafaoğlu, Gökhan; Fairbairn, Andrew; Bianco, Raffaela A.; Julia Gresky (2019-03-19)."Late Pleistocene human genome suggests a local origin for the first farmers of central Anatolia".Nature Communications.10(1): 1218.Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1218F.doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09209-7.ISSN2041-1723.PMC6425003.PMID30890703.

- ^Chacon, Richard J.; Mendoza, Rubén G. (2017).Feast, Famine or Fighting?: Multiple Pathways to Social Complexity.Springer. p. 120.ISBN978-3319484020.

- ^Schmidt, Klaus (2015).Premier temple. Göbekli tepe (Le): Göbelki Tepe(in French). CNRS Editions. p. 291.ISBN978-2271081872.

- ^Collins, Andrew (2014).Gobekli Tepe: Genesis of the Gods: The Temple of the Watchers and the Discovery of Eden.Simon and Schuster. p. 66.ISBN978-1591438359.

- ^Scham, Sandra (November 2008)."The World's First Temple".Archaeology.61(6).Archaeological Institute of America:23.

- ^Kislev, Mordechai E.; Hartmann, Anat;Bar-Yosef, Ofer(June 2, 2006). "Early Domesticated Fig in the Jordan Valley".Science.312(5778).American Association for the Advancement of Science:1372–1374.Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1372K.doi:10.1126/science.1125910.PMID16741119.S2CID42150441.

- ^"Neolithic Age".7 August 2015.

- ^Feldman, Keffie."Ain-Ghazal (Jordan) Pre-pottery Neolithic B Period pit of lime plaster human figures".Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World.Brown University.RetrievedMarch 9,2018.

- ^Zarins, Juris (1992) "Pastoral Nomadism in Arabia: Ethnoarchaeology and the Archaeological Record", inOfer Bar-Yosefand A. Khazanov, eds. "Pastoralism in the Levant"

- ^Killebrew, Ann E.; Steiner, Margreet; Goring-Morris, A. Nigel; Belfer-Cohen, Anna (2013). "The Southern Levant (Cisjordan) During the Neolithic Period".The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant.doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199212972.013.011.ISBN978-0199212972.

- ^Yet another sensational discovery by polish archaeologists in SyriaArchived2011-10-01 at theWayback Machine.eduskrypt.pl. 21 June 2006

- ^"Jericho",Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^Haïdar Boustani, M."The Neolithic of Lebanon in the context of the Near East: State of knowledge"Archived2018-11-16 at theWayback Machine(in French),Annales d'Histoire et d'Archaeologie,Universite Saint-Joseph, Beyrouth, Vol. 12–13, 2001–2002. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^Stordeur, Danielle., Abbès Frédéric.,"Du PPNA au PPNB: mise en lumière d'une phase de transition à Jerf el Ahmar (Syrie)",Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française,Volume 99, Issue 3, pp. 563–595, 2002

- ^PPND – the Platform for Neolithic Radiocarbon Dates – Summary.exoriente. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^Bard, Kathryn (9 March 2014).Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt.Routledge.p. 73.ISBN9780415757539.

- ^Linseele, V.; et al. (July 2010)."Sites with Holocene dung deposits in the Eastern Desert of Egypt: Visited by herders?"(PDF).Journal of Arid Environments.74(7): 818–828.Bibcode:2010JArEn..74..818L.doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.04.014.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2022-03-09.Retrieved2013-09-05.

- ^Hays, Jeffrey (March 2011)."Early Domesticated Animals".Facts and Details.Archived fromthe originalon 21 October 2013.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^Blench, Roger; MacDonald, Kevin C (1999).The Origins and Development of African Livestock.Routledge.ISBN978-1-84142-018-9.

- ^Barker, Graeme (2009).The Agricultural Revolution in Prehistory: Why Did Foragers Become Farmers?.Oxford University Press. pp. 292–293.ISBN978-0-19-955995-4.Retrieved3 December2011.

- ^Alexandra Y. Aĭkhenvalʹd;Robert Malcolm Ward Dixon(2006).Areal Diffussion and Genetic Inheritance: Problems in Comparative Linguistics.Oxford University Press, USA. p. 35.ISBN978-0-19-928308-8.

- ^Fekri A. Hassan (2002).Droughts, food and culture: ecological change and food security in Africa's later prehistory.Springer. pp. 164–.ISBN978-0-306-46755-4.Retrieved3 December2011.

- ^Shillington, Kevin (2005).Encyclopedia of African history: A–G.CRC Press. pp. 521–.ISBN978-1-57958-245-6.Retrieved3 December2011.

- ^abcdSimões, Luciana G.; Günther, Torsten; Martínez-Sánchez, Rafael M.; Vera-Rodríguez, Juan Carlos; Iriarte, Eneko; Rodríguez-Varela, Ricardo; Bokbot, Youssef; Valdiosera, Cristina; Jakobsson, Mattias (7 June 2023)."Northwest African Neolithic initiated by migrants from Iberia and Levant".Nature.618(7965): 550–556.Bibcode:2023Natur.618..550S.doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06166-6.ISSN1476-4687.PMC10266975.PMID37286608.

- ^Marshall, Fiona; Hildebrand, Elisabeth (2002-06-01). "Cattle Before Crops: The Beginnings of Food Production in Africa".Journal of World Prehistory.16(2): 99–143.doi:10.1023/A:1019954903395.ISSN0892-7537.S2CID19466568.

- ^Garcea, Elena A. A. (2004-06-01). "An Alternative Way Towards Food Production: The Perspective from the Libyan Sahara".Journal of World Prehistory.18(2): 107–154.doi:10.1007/s10963-004-2878-6.ISSN0892-7537.S2CID162218030.

- ^Gallinaro, Marina; Lernia, Savino di (2018-01-25)."Trapping or tethering stones (TS): A multifunctional device in the Pastoral Neolithic of the Sahara".PLOS ONE.13(1): e0191765.Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1391765G.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191765.PMC5784975.PMID29370242.

- ^Bower, John (1991-03-01). "The Pastoral Neolithic of East Africa".Journal of World Prehistory.5(1): 49–82.doi:10.1007/BF00974732.ISSN0892-7537.S2CID162352311.

- ^Ambrose, Stanley H. (1984).From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa – "The Introduction of Pastoral Adaptations to the Highlands of East Africa".University of California Press. p. 220.ISBN978-0520045743.Retrieved4 December2014.

- ^Lander=, Faye=; Russell=, Thembi= (14 June 2018)."The Archaeological Evidence for the Appearance of Pastoralism and Farming in Southern Africa".PLOS ONE.13(6): e0198941.Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1398941L.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198941.PMC6002040.PMID29902271.

- ^Dawn Fuller (April 16, 2012)."UC research reveals one of the earliest farming sites in Europe".Phys.org.RetrievedApril 18,2012.

- ^"One of Earliest Farming Sites in Europe Discovered".ScienceDaily.April 16, 2012.RetrievedApril 18,2012.

- ^Curry, Andrew (August 2019)."The first Europeans weren't who you might think".National Geographic.Archived fromthe originalon March 19, 2021.

- ^Spinney, Laura (1 July 2020)."When the First Farmers Arrived in Europe, Inequality Evolved".Scientific American.

- ^Female figurine, c. 6000 BC, Nea Nikomidia, Macedonia, Veroia, (Archaeological Museum), Greece.Macedonian-heritage.gr. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^Winn, Shan (1981).Pre-writing in Southeastern Europe: The Sign System of the Vinča Culture ca. 4000 BC.Calgary: Western Publishers.

- ^Daniel Cilia,"Malta Before Common Era", inThe Megalithic Temples of Malta.Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^Piccolo, Salvatore (2013)Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily,Abingdon-on-Thames, England: Brazen Head Publishing, pp. 33–34ISBN978-0-9565106-2-4

- ^abcShennan & Edinborough 2007.

- ^Timpson, Adrian; Colledge, Sue (September 2014)."Reconstructing regional population fluctuations in the European Neolithic using radiocarbon dates: a new case-study using an improved method".Journal of Archaeological Science.52:549–557.Bibcode:2014JArSc..52..549T.doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.08.011.

- ^Coningham, Robin;Young, Ruth (2015),The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BC – 200 CE,Cambridge University PressQuote: "" Mehrgarh remains one of the key sites in South Asia because it has provided the earliest known undisputed evidence for farming and pastoral communities in the region, and its plant and animal material provide clear evidence for the ongoing manipulation, and domestication, of certain species. Perhaps most importantly in a South Asian context, the role played by zebu makes this a distinctive, localised development, with a character completely different to other parts of the world. Finally, the longevity of the site, and its articulation with the neighbouring site of Nausharo (c. 2800–2000 BC), provides a very clear continuity from South Asia's first farming villages to the emergence of its first cities (Jarrige, 1984). "

- ^Fisher, Michael H. (2018),An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century,Cambridge University Press,ISBN978-1-107-11162-2Quote: "page 33:" The earliest discovered instance in India of well-established, settled agricultural society is at Mehrgarh in the hills between the Bolan Pass and the Indus plain (today in Pakistan) (see Map 3.1). From as early as 7000 BC, communities there started investing increased labor in preparing the land and selecting, planting, tending, and harvesting particular grain-producing plants. They also domesticated animals, including sheep, goats, pigs, and oxen (both humped zebu [Bos indicus] and unhumped [Bos taurus]). Castrating oxen, for instance, turned them from mainly meat sources into domesticated draft-animals as well. "

- ^Dyson, Tim (2018),A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day,Oxford University Press,ISBN978-0-19-882905-8,Quote: "(p 29)" The subcontinent's people were hunter-gatherers for many millennia. There were very few of them. Indeed, 10,000 years ago there may only have been a couple of hundred thousand people, living in small, often isolated groups, the descendants of various 'modern' human incomers. Then, perhaps linked to events in Mesopotamia, about 8,500 years ago agriculture emerged in Baluchistan. "

- ^Wright, Rita P.(2009),The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society,Cambridge University Press, pp. 44, 51,ISBN978-0-521-57652-9

- ^Coppa, A.; Bondioli, L.; Cucina, A.; Frayer, D. W.; Jarrige, C.; Jarrige, J. -F.; Quivron, G.; Rossi, M.; Vidale, M.; Macchiarelli, R. (2006). "Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry".Nature.440(7085): 755–756.Bibcode:2006Natur.440..755C.doi:10.1038/440755a.ISSN0028-0836.PMID16598247.S2CID6787162.

- ^Eleni Asouti and Dorian Q Fuller (2007).Trees and Woodlands of South India: Archaeological Perspectives.

- ^Xiaoyan Yang (2012)."Early millet use in northern China".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.109(10): 3726–3730.Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.3726Y.doi:10.1073/pnas.1115430109.PMC3309722.PMID22355109.

- ^"New Archaeological Discoveries and Researches in 2004 – The Fourth Archaeology Forum of CASS".Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.April 28, 2005.RetrievedSeptember 18,2007.

- ^Liu, Li; Chen, Xingcan (2012),The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age,Cambridge University Press, pp. 220, 227, 251

- ^The Archaeology News Network. 2012."Neolithic farm field found in South Korea"Archived2012-11-20 at theWayback Machine.

- ^The Korea Times(2012)."East Asia's oldest remains of agricultural field found in Korea".

- ^Willey, Gordon R.; Phillips, Philip (1957).Method and Theory in American Archaeology.University of Chicago Press.ISBN978-0-226-89888-9.

- ^Kohler TA; M Glaude; JP Bocquet-Appel; Brian M Kemp (2008). "The Neolithic Demographic Transition in the North American Southwest".American Antiquity.73(4): 645–669.doi:10.1017/s000273160004734x.hdl:2376/5746.S2CID163007590.

- ^A. Eichler, G. Gramlich, T. Kellerhals, L. Tobler, Th. Rehren & M. Schwikowski (2017). "Ice-core evidence of earliest extensive copper metallurgy in the Andes 2700 years ago"

- ^White, Peter,"Revisiting the 'Neolithic Problem' in Australia" PDF,2006

- ^abLeonard D. Katz Rigby; S. Stephen Henry Rigby (2000).Evolutionary Origins of Morality: Cross-disciplinary Perspectives.United Kingdom: Imprint Academic. p. 158.ISBN0-7190-5612-8.

- ^Langer, Jonas; Killen, Melanie (1998).Piaget, evolution, and development.Psychology Press. pp. 258–.ISBN978-0-8058-2210-6.Retrieved3 December2011.

- ^"The Oldest Civilization in the Americas Revealed"(PDF).CharlesMann.Science. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 10 October 2015.Retrieved9 October2015.

- ^"First Andes Civilization Explored".BBC News. 22 December 2004.Retrieved9 October2015.

- ^Hommon, Robert J. (2013).The ancient Hawaiian state: origins of a political society(First ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-991612-2.

- ^"Stone Age", Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007© 1997–2007 Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Contributed by Kathy Schick, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. and Nicholas Toth, B.A., M.A., Ph.D.Archived2009-11-01.

- ^abRussell Dale Guthrie (2005).The nature of Paleolithic art.University of Chicago Press. pp. 420–.ISBN978-0-226-31126-5.Retrieved3 December2011.

- ^"Farming Pioneered in Ancient New Guinea".New Scientist.Retrieved9 October2015.

- ^abBahn, Paul (1996) "The atlas of world archeology" Copyright 2000 The brown Reference Group plc

- ^"Prehistoric Cultures".Museum of Ancient and Modern Art. 2010. Archived fromthe originalon 3 August 2018.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^Hirst, K. Kris."Çatalhöyük: Urban Life in Neolithic Anatolia".About.com Archaeology.About.com. Archived fromthe originalon 21 October 2013.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^Idyllic Theory of Goddess Creates StormArchived2008-02-19 at theWayback Machine.Holysmoke.org. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^Krause (1998) under External links, places.

- ^Gimbutas (1991) page 143.

- ^Kuijt, Ian (2000).Life in Neolithic farming communities: social organization, identity, and differentiation.Springer. pp. 317–.ISBN978-0-306-46122-4.Retrieved3 December2011.

- ^Gil Stein, "Economy, Ritual and Power in 'Ubaid Mesopotamia" inChiefdoms and Early States in the Near East: The Organizational Dynamics of Complexity.

- ^Timothy Earle, "Property Rights and the Evolution of Chiefdoms" inChiefdoms: Power, Economy, and Ideology.

- ^abShane, Orrin C. III, and Mine Küçuk. "The World's First City."Archived2008-03-15 at theWayback MachineArchaeology 51.2 (1998): 43–47.

- ^Alan W. Ertl (2008).Toward an Understanding of Europe: A Political Economic Précis of Continental Integration.Universal-Publishers. p. 308.ISBN978-1-59942-983-0.Retrieved28 March2011.

- ^Harris, Susanna (2009)."Smooth and Cool, or Warm and Soft: Investigating the Properties of Cloth in Prehistory".North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles X.Academia.edu.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^"Aspects of Life During the Neolithic Period"(PDF).Teachers' Curriculum Institute. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 5 May 2016.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^Gibbs, Kevin T. (2006)."Pierced clay disks and Late Neolithic textile production".Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East.Academia.org.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^Green, Jean M (1993). "Unraveling the Enigma of the Bi: The Spindle Whorl as the Model of the Ritual Disk".Asian Perspectives.32(1). University of Hawai'i Press: 105–24.hdl:10125/17022.

- ^Cook, M (2007). "The clay loom weight, in: Early Neolithic ritual activity, Bronze Age occupation and medieval activity at Pitlethie Road, Leuchars, Fife".Tayside and Fife Archaeological Journal.13:1–23.

- ^Mazurowski, Ryszard F.; Kanjou, Youssef, eds. (2012).Tell Qaramel 1999–2007. Protoneolithic and early Pre-Pottery Neolithic settlement in Northern Syria.PCMA Excavation Series 2. Warsaw, Poland: Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw.ISBN978-83-903796-3-0.

- ^E. J. Peltenburg; Alexander Wasse; Council for British Research in the Levant (2004).Garfinkel, Yosef., "Néolithique" and "Énéolithique" Byblos in Southern Levantine Context in Neolithic revolution: new perspectives on southwest Asia in light of recent discoveries on Cyprus.Oxbow Books.ISBN978-1-84217-132-5.Retrieved18 January2012.

- ^abOstaptchouk, Dr."Contribution of FTIR to the Characterization of the Raw Material for" Flint "Chipped Stone and for Beads from Mentesh Tepe and Kamiltepe (Azerbaijan). Preliminary Results".

- ^Davis K. Thanjan (12 January 2011).Pebbles.Bookstand Publishing. pp. 31–.ISBN978-1-58909-817-6.Retrieved4 July2011.

- ^Developed Neolithic period, 5500 BCArchived2011-03-11 at theWayback Machine.Eliznik.org.uk. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^"Manunggul Burial Jar".Virtual Collection of Asian Masterpieces.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^"Tabon Cave Complex".National Museum of the Philippines. 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 25 February 2021.Retrieved5 September2013.

- ^"Neolithic Culture of Tamil Nadu: an Overview"(PDF).

Sources[edit]

- Bellwood, Peter(November 30, 2004).First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies.Wiley-Blackwell.p. 384.ISBN978-0-631-20566-1.

- Shennan, Stephen; Edinborough, Kevan (2007). "Prehistoric population history: From the Late Glacial to the Late Neolithic in Central and Northern Europe".Journal of Archaeological Science.34(8): 1339–45.Bibcode:2007JArSc..34.1339S.doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.10.031.

Further reading[edit]

- Pedersen, Hilthart (2008).Die Jüngere Steinzeit Auf Bornholm.GRIN Verlag.ISBN978-3-638-94559-2.

External links[edit]

- Romeo, Nick (Feb. 2015).Embracing Stone Age Couple Found in Greek Cave."Rare double burials discovered at one of the largest Neolithic burial sites in Europe."National Geographic Society

- McNamara, John (2005)."Neolithic Period".World Museum of Man. Archived fromthe originalon 2008-04-30.Retrieved2008-04-14.

- Affonso, T.; Pernicka, E. (2000). "Pre-Pottery Neolithic Clay Figurines from Nevali Çori".Internet Archaeology(9).doi:10.11141/ia.9.4.

- .Encyclopædia Britannica(11th ed.). 1911.