Nineteen Eighty-Four

First-edition cover | |

| Author | George Orwell |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Michael Kennard[1] |

| Language | English |

| Genre | |

| Set in | London,Airstrip One, Oceania |

| Publisher | Secker & Warburg |

Publication date | 8 June 1949 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 328 |

| OCLC | 470015866 |

| 823.912[2] | |

| LC Class | PZ3.O793 Ni2 |

| Preceded by | Animal Farm |

Nineteen Eighty-Four(also published as1984) is adystopian novelandcautionary taleby English writer Eric Arthur Blair, who wrote under the pen nameGeorge Orwell.It was published on 8 June 1949 bySecker & Warburgas Orwell's ninth and final book completed in his lifetime. Thematically, it centres on the consequences oftotalitarianism,mass surveillance,andrepressive regimentationof people and behaviours within society.[3][4]Orwell, a staunch believer indemocratic socialismand member of theanti-Stalinist Left,modelled the Britain underauthoritarian socialismin the novel on theSoviet Unionin the era ofStalinismand on the very similar practices of bothcensorshipandpropagandainNazi Germany.[5]More broadly, the novel examines the role of truth and facts within societies and the ways in which they can be manipulated.

The story takes place in an imagined future. The current year is uncertain, but believed to be 1984. Much of the world is inperpetual war.Great Britain, now known as Airstrip One, has become a province of the totalitariansuperstateOceania,which is led byBig Brother,a dictatorial leader supported by an intensecult of personalitymanufactured by the Party'sThought Police.The Party engages inomnipresent government surveillanceand, through theMinistry of Truth,historical negationismand constantpropagandato persecute individuality and independent thinking.[6]

The protagonist,Winston Smith,is a diligent mid-level worker at the Ministry of Truth who secretly hates the Party and dreams of rebellion. Smith keeps a forbidden diary. He begins a relationship with a colleague,Julia,and they learn about a shadowy resistance group called the Brotherhood. However, their contact within the Brotherhood turns out to be a Party agent, and Smith and Julia are arrested. He is subjected to months of psychological manipulation and torture by the Ministry of Love. He ultimately betrays Julia and is released; he finally realises he loves Big Brother.

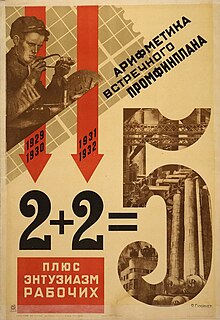

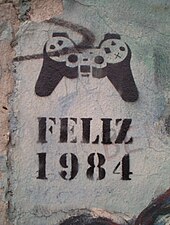

Nineteen Eighty-Fourhas become a classic literary example of political and dystopian fiction. It also popularised the term "Orwellian"as an adjective, with many terms used in the novel entering common usage, including" Big Brother ","doublethink","Thought Police ","thoughtcrime","Newspeak",and"2 + 2 = 5".Parallels have been drawn between the novel's subject matter andreal lifeinstances of totalitarianism, mass surveillance, and violations offreedom of expression,among other themes.[7][8][9]Orwell described his book as a "satire",[10]and a display of the "perversions to which a centralised economy is liable," while also stating he believed "that something resembling it could arrive."[10]Timeincluded the novel on its list of the 100 best English-language novels published from 1923 to 2005,[11]and it was placed on theModern Library's 100 Best Novelslist, reaching number 13 on the editors' list and number 6 on the readers' list.[12]In 2003, it was listed at number eight onThe Big Readsurvey by theBBC.[13]It has been adapted across media since its publication, most notably as a film,released in 1984,starringJohn Hurt,Suzanna HamiltonandRichard Burton,and as an audio drama in 2024 starringAndrew Garfield,Andrew Scott,Cynthia ErivoandTom Hardy.

Writing and publication

[edit]Idea

[edit]The Orwell Archive at University College London contains undated notes about ideas that evolved intoNineteen Eighty-Four.The notebooks have been deemed "unlikely to have been completed later than January 1944", and "there is a strong suspicion that some of the material in them dates back to the early part of the war".[14]

In one 1948 letter, Orwell claims to have "first thought of [the book] in 1943", while in another he says he thought of it in 1944 and cites 1943'sTehran Conferenceas inspiration: "What it is really meant to do is to discuss the implications of dividing the world up into 'Zones of Influence' (I thought of it in 1944 as a result of the Tehran Conference), and in addition to indicate by parodying them the intellectual implications of totalitarianism".[14]Orwell had toured Austria in May 1945 and observed manoeuvring he thought would probably lead to separate Soviet and Allied Zones of Occupation.[15][16]

In January 1944, literature professorGleb Struveintroduced Orwell toYevgeny Zamyatin's 1924 dystopian novelWe.In his response Orwell expressed an interest in the genre, and informed Struve that he had begun writing ideas for one of his own, "that may get written sooner or later."[17][18]In 1946, Orwell wrote about the 1931 dystopian novelBrave New WorldbyAldous Huxleyin his article "Freedom and Happiness" for theTribune,and noted similarities toWe.[17]By this time Orwell had scored a critical and commercial hit with his 1945 political satireAnimal Farm,which raised his profile. For a follow-up he decided to produce a dystopian work of his own.[19][20]

Writing

[edit]In a June 1944 meeting withFredric Warburg,co-founder of his British publisherSecker & Warburg,shortly before the release ofAnimal Farm,Orwell announced that he had written the first 12 pages of his new novel. He could only earn a living from journalism, however, and predicted the book would not see a release before 1947.[18]Progress was slow; by the end of September 1945 Orwell had written some 50 pages.[21]Orwell became disenchanted with the restrictions and pressures involved with journalism and grew to detest city life in London.[22]He suffered frombronchiectasisand a lesion in one lung; the harsh winter worsened his health.[23]

In May 1946, Orwell arrived on the Scottish island ofJura.[20]He had wanted to retreat to a Hebridean island for several years;David Astorrecommended he stay atBarnhill,a remote farmhouse on the island that his family owned,[24]with no electricity or hot water. Here Orwell intermittently drafted and finishedNineteen Eighty-Four.[20]His first stay lasted until October 1946, during which time he made little progress on the few already completed pages, and at one point did no work on it for three months.[25]After spending the winter in London, Orwell returned to Jura; in May 1947 he reported to Warburg that despite progress being slow and difficult, he was roughly a third of the way through.[26]He sent his "ghastly mess" of a first draft manuscript to London, where Miranda Christen volunteered to type a clean version.[27]Orwell's health worsened further in September, however, and he was confined to bed with inflammation of the lungs. He lost almost two stone (28 pounds or 12.7 kg) in weight and had recurring night sweats, but he decided not to see a doctor and continued writing.[28]On 7 November 1947, he completed the first draft in bed, and subsequently travelled toEast Kilbridenear Glasgow for medical treatment atHairmyres Hospital,where a specialist confirmed a chronic and infectious case of tuberculosis.[29][27]

Orwell was discharged in the summer of 1948, after which he returned to Jura and produced a full second draft ofNineteen Eighty-Four,which he finished in November. He asked Warburg to have someone come to Barnhill and retype the manuscript, which was so untidy that the task was only considered possible if Orwell was present, as only he could understand it. The previous volunteer had left the country and no other could be found at short notice, so an impatient Orwell retyped it himself at a rate of roughly 4,000 words a day during bouts of fever and bloody coughing fits.[27]On 4 December 1948, Orwell sent the finished manuscript to Secker & Warburg and left Barnhill for good in January 1949. He recovered at a sanitarium in theCotswolds.[27]

Title

[edit]Shortly before completion of the second draft, Orwell vacillated between two titles for the novel:The Last Man in Europe,an early title, andNineteen Eighty-Four.[30]Warburg suggested the latter, which he took to be a more commercially viable choice.[31]There has been a theory – doubted by Dorian Lynskey (author of a2019 book aboutNineteen Eighty-Four) – that1984was chosen simply as an inversion of the year 1948, the year in which it was being completed. Lynskey says the idea was "first suggested by Orwell's US publisher", and it was also mentioned byChristopher Hitchensin his introduction to the 2003 edition ofAnimal Farm and 1984,which also notes that the date was meant to give "an immediacy and urgency to the menace of totalitarian rule".[32]However, Lynskey does not believe the inversion theory:

This idea... seems far too cute for such a serious book.... Scholars have raised other possibilities. [His wife] Eileen wrote a poem for her old school's centenary called 'End of the Century: 1984.'G. K. Chesterton's 1904 political satireThe Napoleon of Notting Hill,which mocks the art of prophecy, opens in 1984. The year is also a significant date inThe Iron Heel.But all of these connections are exposed as no more than coincidences by the early drafts of the novel... First he wrote 1980, then 1982, and only later 1984. The most fateful date in literature was a late amendment.[33]

Publication

[edit]

In the run up to publication, Orwell called the novel "abeastlybook "and expressed some disappointment towards it, thinking it would have been improved had he not been so ill. This was typical of Orwell, who had talked down his other books shortly before their release.[33]Nevertheless, the book was enthusiastically received by Secker & Warburg, who acted quickly; before Orwell had left Jura he rejected their proposed blurb that portrayed it as "a thriller mixed up with a love story."[33]He also refused a proposal from the American Book of the Month Club to release an edition without the appendix and chapter on Goldstein's book, a decision which Warburg claimed cut off about £40,000 in sales.[33][34]

Nineteen Eighty-Fourwas published on 8 June 1949 in the UK;[33][35][36]Orwell predicted earnings of around £500. A first print of 25,575 copies was followed by a further 5,000 copies in March and August 1950.[37]The novel had the most immediate impact in the US, following its release there on 13 June 1949 byHarcourt Brace, & Co.An initial print of 20,000 copies was quickly followed by another 10,000 on 1 July, and again on 7 September.[38]By 1970, over 8 million copies had been sold in the US, and in 1984 it topped the country's all-time best seller list.[39]

In June 1952, Orwell's widow Sonia Bronwell sold the only surviving manuscript at a charity auction for £50.[40]The draft remains the only surviving literary manuscript from Orwell, and is held at theJohn Hay LibraryatBrown UniversityinProvidence, Rhode Island.[41][42]

Variant English language editions

[edit]In the original published UK and US editions of 1984 numerous small variations in the text exist, the US edition altering Orwell's agreed edit of the text as was typical of publishing practices of the time in regard to spelling and punctuation, as well as some small edits and phrasings. While Orwell rejected a proposed book club edition which would see substantial sections of the book removed, these minor changes passed somewhat under the radar. Other more significant revisions and variant texts also exist however.

In 1984 Peter Davison editedNineteen Eighty-Four: The Facsimile of the Extant Manuscript,published by Secker and Warburg in the UK and Harcourt-Brace-Jovanovich in the US. This reproduced page for page Sonia Bronwell's copy of the original manuscript in facsimiles, as well as a complete typeset versions of that text - complete with Orwell's holograph and typewritten pages, and handwritten amendments and corrections. The book had a preface by Daniel Segal. It has been reprinted in various international editions with translated introductions and notes, and reprinted in English in limited edition formats.

In 1997, Davison produced a definitive text ofNineteen Eighty Fouras part of Secker's 20 volume definitive edition of theComplete Works of George Orwell.This edition removed errors, typographic errors, and reversed editorial changes in the original editions made without Orwell's oversight, all based on detailed reference to Orwell's original manuscript and notes. This text has gone on to be reprinted in various subsequent paperback editions, including one with an introduction byThomas Pynchon,without obvious note that it is a revised text, and has been translated as an unexpurgated version of text.

In 2021 Polygon publishedNineteen Eighty Four: The Jura Edition,with an introduction by Alex Massie.

Plot

[edit]In an uncertain year, believed to be 1984, civilisation has been ravaged by world war, civil conflict, and revolution. Airstrip One (formerly known asGreat Britain) is a province ofOceania,one of the threetotalitariansuper-states that rule the world. It is ruled by "The Party" under the ideology of "Ingsoc"(aNewspeakshortening of "English Socialism" ) and the mysterious leaderBig Brother,who has an intensecult of personality.The Party brutally purges out anyone who does not fully conform to their regime, using theThought Policeand constant surveillance throughtelescreens(two-way televisions), cameras, and hidden microphones. Those who fall out of favour with the Party become "unpersons", disappearing withall evidence of their existence destroyed.

InLondon,Winston Smithis a member of the Outer Party, working at theMinistry of Truth,where herewrites historical recordsto conform to the state's ever-changing version of history. Winston revises past editions ofThe Times,while the original documents are destroyed after being dropped into ducts known asmemory holes,which lead to an immense furnace. He secretly opposes the Party's rule and dreams of rebellion, despite knowing that he is already a "thought-criminal"and is likely to be caught one day.

While in aproleneighbourhood he meets Mr. Charrington, the owner of an antiques shop, and buys a diary where he writes criticisms of the Party and Big Brother. To his dismay, when he visits a prole quarter he discovers they have no political consciousness. As he works in the Ministry of Truth, he observesJulia,a young woman maintaining the novel-writing machines at the ministry, whom Winston suspects of being a spy, and develops an intense hatred of her. He vaguely suspects that his superior,Inner PartyofficialO'Brien,is part of an enigmatic undergroundresistance movementknown as the Brotherhood, formed by Big Brother's reviled political rivalEmmanuel Goldstein.

One day, Julia secretly hands Winston a love note, and the two begin a secret affair. Julia explains that she also loathes the Party, but Winston observes that she is politically apathetic and uninterested in overthrowing the regime. Initially meeting in the country, they later meet in a rented room above Mr. Charrington's shop. During the affair, Winston remembers the disappearance of his family during the civil war of the 1950s and his tense relationship with his estranged wife Katharine. Weeks later, O'Brien invites Winston to his flat, where he introduces himself as a member of the Brotherhood and sends Winston a copy ofThe Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivismby Goldstein. Meanwhile, during the nation's Hate Week, Oceania's enemy suddenly changes fromEurasiatoEastasia,which goes mostly unnoticed. Winston is recalled to the Ministry to help make the necessary revisions to the records. Winston and Julia read parts of Goldstein's book, which explains how the Party maintains power, the true meanings of its slogans, and the concept ofperpetual war.It argues that the Party can be overthrown if proles rise up against it. However, Winston never gets the opportunity to read the chapter that explains why the Party took power and is motivated to maintain it.

Winston and Julia are captured when Mr. Charrington is revealed to be an undercover Thought Police agent, and they are separated and imprisoned at theMinistry of Love.O'Brien also reveals himself to be a member of the Thought Police and a member of afalse flagoperation which catches political dissidents of the Party. Over several months, Winston is starved and relentlessly tortured to bring his beliefs in line with the Party. O'Brien tells Winston that he will never know whether the Brotherhood actually exists and that Goldstein's book was written collaboratively by him and other Party members; furthermore, O'Brien reveals to Winston that the Party sees power not as a means but as an end, and the ultimate purpose of the Party is seeking power entirely for its own sake. For the final stage of re-education, O'Brien takes Winston toRoom 101,which contains each prisoner's worst fear. When confronted with rats, Winston denounces Julia and pledges allegiance to the Party.

Winston is released into public life and continues to frequent the Chestnut Tree café. He encounters Julia, and both reveal that they have betrayed the other and are no longer in love. Back in the café, a news alert celebrates Oceania's supposed massive victory over Eurasian armies in Africa. Winston finally accepts that he loves Big Brother.

Characters

[edit]Main characters

[edit]- Winston Smith:the 39-year old protagonist who is a phlegmaticeverymanharbouring thoughts of rebellion and is curious about the Party's power and the past before the Revolution.

- Julia:Winston's lover who publicly espouses Party doctrine as a member of the fanatical Junior Anti-Sex League. Julia enjoys her small acts of rebellion and has no interest in giving up her lifestyle.

- O'Brien:A mysterious character, O'Brien is a member of the Inner Party who poses as a member of The Brotherhood, the counter-revolutionary resistance, to catch Winston. He is a spy intending to deceive, trap, and capture Winston and Julia.

- Big Brother and Emmanuel Goldstein never appear but play a big part in the plot and have a significant role in theworldbuildingof 1984.

- Big Brother:the leader and figurehead of the Party that rules Oceania. A deepcult of personalityis formed around him. It is not revealed whether he actually exists.

- Emmanuel Goldstein:ostensibly a former leading figure in the Party who became the counter-revolutionary leader of the Brotherhood, and author of the bookThe Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism.Goldstein is the symbolicenemy of the state—the nationalnemesiswho ideologically unites the people of Oceania with the Party, especially during theTwo Minutes Hateand other forms of fearmongering. However O'Brien claims that the book was actually written by the Party.

Secondary characters

[edit]- Aaronson, Jones, and Rutherford: former members of the Inner Party whom Winston vaguely remembers as among the original leaders of the Revolution, long before he had heard of Big Brother. They confessed to treasonable conspiracies with foreign powers and were then executed in the political purges of the 1960s. In between their confessions and executions, Winston saw them drinking in the Chestnut Tree Café—with broken noses, suggesting that their confessions had been obtained by torture. Later, in the course of his editorial work, Winston sees newspaper evidence contradicting their confessions, but drops it into amemory hole.Eleven years later, he is confronted with the same photograph during his interrogation.

- Ampleforth: Winston's one-time Records Department colleague who was imprisoned for leaving the word "God" in aKiplingpoem as he could not find another rhyme for "rod";[44]Winston encounters him at theMinistry of Love.Ampleforth is a dreamer and intellectual who takes pleasure in his work, and respects poetry and language, traits which cause him disfavour with the Party.

- Charrington: an undercover officer of theThought Policemasquerading as a kind and sympathetic antiques dealer amongst the proles.

- Katharine Smith: the emotionally indifferent wife whom Winston "can't get rid of". Despite disliking sexual intercourse, Katharine married Winston because it was their "duty to the Party". Although she was a "goodthinkful" ideologue, they separated because the couple could not conceive children. Divorce is not permitted, but couples who cannot have children may live separately. For much of the story Winston lives in vague hope that Katharine may die or could be "got rid of" so that he may marry Julia. He regrets not having killed her by pushing her over the edge of a quarry when he had the chance many years previously.

- The Parsons family:

- Tom Parsons: Winston's naïve neighbour, and an ideal member of the Outer Party: an uneducated, suggestible man who is utterly loyal to the Party, and fully believes in its perfect image. He is socially active and participates in the Party activities for his social class. He is friendly towards Smith, and despite his political conformity punishes his bullying son for firing acatapultat Winston. Later, as a prisoner, Winston sees Parsons imprisoned in the Ministry of Love, after his young daughter reported him to the Thought Police for speaking against Big Brother in his sleep. Even this does not dampen Parsons's belief in the Party—he says he could do "good work" in the hard labour camps.

- Mrs. Parsons: Parsons's wife is a wan and hapless woman who is intimidated by her own children.

- The Parsons children: a nine-year-old son and seven-year-old daughter. Both are members of the Spies, a youth organisation that focuses on indoctrinating children with Party ideals and training them to report any suspected incidents of unorthodoxy. They represent the new generation of Oceanian citizens, the model society envisioned by the Inner Party without memory of life before Big Brother, and without family ties or emotional sentiment.

- Syme: Winston's colleague at the Ministry of Truth, alexicographerinvolved in compiling a new edition of theNewspeakdictionary. Although he is enthusiastic about his work and support for the Party, Winston notes, "He is too intelligent. He sees too clearly and speaks too plainly." Winston predicts, correctly, that Syme will become an unperson.

Setting

[edit]This section has multiple issues.Please helpimprove itor discuss these issues on thetalk page.(Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

History of the world

[edit]The Revolution

[edit]Winston Smith's memories and his reading of the proscribed book,The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical CollectivismbyEmmanuel Goldstein,reveal that after theSecond World War,aThird World Warbroke out in the early 1950s in whichnuclear weaponsdestroyed hundreds of cities in Europe, western Russia and North America (though not stated, it is implied this was a nuclear exchange between the United States and theSoviet Union).Colchesterwas destroyed, and London also suffered widespread aerial raids, leading Winston's family to take refuge in aLondon Undergroundstation.

During the war, the Soviet Union invaded and absorbed all of Continental Europe, while the United States absorbed theBritish Commonwealthand later Latin America. This formed the basis of Eurasia and Oceania respectively. Due to the instability perpetuated by the nuclear war, these new nations fell into civil war, but who fought whom is left unclear (there is a reference to the child Winston having seen rival militias in the streets, each one having a shirt of a distinct colour for its members). Meanwhile, Eastasia, the last superstate established, emerged only after "a decade of confused fighting". It includes the Asian lands conquered by China and Japan. Although Eastasia is prevented from matching Eurasia's size, its larger populace compensates for that handicap.

However, due to the fact that Winston only barely remembers these events as well as the Party's constant manipulation of historical records, the continuity and accuracy of these events are unknown, and exactly how the superstates' ruling parties managed to gain their power is also left unclear. If the official account was accurate, Smith's strengthening memories and the story of his family's dissolution suggest that the atomic bombings occurred first, followed by civil war featuring "confused street fighting in London itself" and the societal postwar reorganisation, which the Party retrospectively calls "the Revolution". It is very difficult to trace the exact chronology, but most of the global societal reorganisation occurred between 1945 and the early 1960s.

The War

[edit]In 1984, there is a perpetual war between Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia, the superstates that emerged from the global atomic war.The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism,by Emmanuel Goldstein, explains that each state is so strong that it cannot be defeated, even with the combined forces of two superstates, despite changing alliances. To hide such contradictions, the superstates' governments rewrite history to explain that the (new) alliance always was so; the populaces are already accustomed to doublethink and accept it. The war is not fought in Oceanian, Eurasian or Eastasian territory but in the Arctic wastes and a disputed zone roughly situated in betweenTangiers,Brazzaville,DarwinandHong Kong.At the start, Oceania and Eastasia are allies fighting Eurasia in northern Africa and theMalabar Coast.

That alliance ends, and Oceania, allied with Eurasia, fights Eastasia, a change occurring on Hate Week, dedicated to creating patriotic fervour for the Party's perpetual war. The public are blind to the change; in mid-sentence, an orator changes the name of the enemy from "Eurasia" to "Eastasia" without pause. When the public are enraged at noticing that the wrong flags and posters are displayed, they tear them down; the Party later claims to have captured the whole of Africa.

Goldstein's book explains that the purpose of the unwinnable, perpetual war is to consume human labour and commodities so that the economy of a superstate cannot support economic equality, with a high standard of life for every citizen. By using up most of the produced goods, the proles are kept poor and uneducated, and the Party hopes that they will neither realise what the government is doing nor rebel. Goldstein also details an Oceanian strategy of attacking enemy cities with atomic rockets before invasion but dismisses it as unfeasible and contrary to the war's purpose; despite the atomic bombing of cities in the 1950s, the superstates stopped it for fear that it would imbalance the powers. The military technology in the novel differs little from that of World War II, but strategic bomber aeroplanes are replaced withrocket bombs,helicopterswere heavily used as weapons of war (theywere very minorin World War II) and surface combat units have been all but replaced by immense and unsinkable Floating Fortresses (island-like contraptions concentrating the firepower of a whole naval task force in a single, semi-mobile platform; in the novel, one is said to have been anchored betweenIcelandand theFaroe Islands,suggesting a preference for sea lane interdiction and denial).

Political geography

[edit]

Three perpetually warringtotalitariansuperstates control the world in the novel:[45]

- Oceania (ideology:Ingsoc,known in Oldspeak as English Socialism), whose core territories are "theAmericas,theAtlantic Islands,including theBritish Isles,Australasiaand thesouthern portion of Africa".

- Eurasia (ideology: Neo-Bolshevism), whose core territories are "the whole of the northern part of theEuropeanandAsiatic landmassfromPortugalto theBering Strait".

- Eastasia (ideology: Obliteration of the Self, also known as Death-Worship), whose core territories are "Chinaandthe countries to the south of it,theJapanese islands,and a large but fluctuating portion ofManchuria,MongoliaandTibet".

The perpetual war is fought for control of the "disputed area" lying between the frontiers of the superstates. The majority of the disputed territories form "a roughquadrilateralwith its corners atTangier,Brazzaville,DarwinandHong Kong",where ~of the world's population resides. Orwell outlines the highest disputed areas asEquatorial Africa,North Africa,theMiddle East,Indian subcontinentandIndonesia.Fighting also takes place along the unstable Eurasian-Eastasian border, over various islands in theIndianandPacific Ocean,aroundFloating Fortressesalong major "sea lines",as well as around theNorth Pole.[45]

Ministries of Oceania

[edit]In London, the capital city of Airstrip One, Oceania's four government ministries are in pyramids (300 m high), the façades of which display the Party's three slogans – "WAR IS PEACE", "FREEDOM IS SLAVERY", "IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH". The ministries are deliberately named after the opposite (doublethink) of their true functions: "The Ministry of Peace concerns itself with war, the Ministry of Truth with lies, the Ministry of Love with torture and the Ministry of Plenty with starvation." (Part II, chapter IX "The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism" (by Emmanuel Goldstein)).

While a ministry is supposedly headed by a minister, the ministers heading these four ministries are never mentioned. They seem to be completely out of the public view, Big Brother being the only, ever-present public face of the government. Also, while an army fighting a war is typically headed by generals, none are ever mentioned by name. News reports of the ongoing war assume that Big Brother personally commands Oceania's fighting forces and give him personal credit for victories and successful strategic concepts.

Ministry of Peace

[edit]The Ministry of Peace maintains Oceania's perpetual war against either of the two other superstates:

The primary aim of modern warfare (in accordance with the principles of doublethink, this aim is simultaneously recognised and not recognised by the directing brains of the Inner Party) is to use up the products of the machine without raising the generalstandard of living.Ever since the end of the nineteenth century, the problem of what to do with the surplus of consumption goods has been latent in industrial society. At present, when few human beings even have enough to eat, this problem is obviously not urgent, and it might not have become so, even if no artificial processes of destruction had been at work.

Ministry of Plenty

[edit]The Ministry of Plenty rations and controls food, goods, and domestic production; every fiscal quarter, it claims to have raised the standard of living, even during times when it has, in fact, reduced rations, availability, and production. The Ministry of Truth substantiates the Ministry of Plenty's claims bymanipulating historical recordsto report numbers supporting the claims of "increased rations". The Ministry of Plenty also runs the national lottery as a distraction for the proles; Party members understand it to be a sham in which all the larger prizes are "won" by imaginary people; only small amounts are actually paid out.

Ministry of Truth

[edit]The Ministry of Truth controls information: news, entertainment, education, and the arts. Winston Smith works in the Records Department, "rectifying" historical records to accord with Big Brother's current pronouncements so that everything the Party says appears to be true.

Ministry of Love

[edit]The Ministry of Love identifies, monitors, arrests and converts real and imagined dissidents. This is also the place where the Thought Police beat and torture dissidents, after which they are sent to Room 101 to face "the worst thing in the world" —until love for Big Brother and the Party replaces dissension.

Major concepts

[edit]This sectionneeds additional citations forverification.(June 2022) |

Ingsoc (English Socialism) is the predominant ideology andphilosophyof Oceania, andNewspeakis the official language of official documents. Orwell depicts the Party's ideology as anoligarchicalworld view that "rejects and vilifies every principle for which the Socialist movement originally stood, and it does so in the name of Socialism."[46]

Big Brother

[edit]Big Brotheris a fictional character and symbol in the novel. He is ostensibly the leader of Oceania, atotalitarianstate wherein the ruling partyIngsocwields total power "for its own sake". In the society that Orwell describes, every citizen (except of the proles, who are regarded as little more than animals) is under constantsurveillanceby the authorities, mainly bytelescreens.The people are constantly reminded of this by the widely displayed slogan "Big Brother is watching you".

In modern culture, the term "Big Brother" has entered thelexiconas a synonym for abuse of government power, particularly in respect tomass surveillance.[47]

Doublethink

[edit]The keyword here is blackwhite. Like so many Newspeak words, this word has two mutually contradictory meanings. Applied to an opponent, it means the habit of impudently claiming that black is white, in contradiction of the plain facts. Applied to a Party member, it means a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this. But it means also the ability to believe that black is white, and more, to know that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary. This demands a continuous alteration of the past, made possible by the system of thought which really embraces all the rest, and which is known in Newspeak as doublethink. Doublethink is basically the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one's mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.

— Part II, chapter IX "The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism"(by Emmanuel Goldstein)

Newspeak

[edit]The Principles of Newspeakis an academic essay appended to the novel. It describes the development of Newspeak, an artificial, minimalistic language designed to ideologically align thought with the principles of Ingsoc by stripping down the English language in order to make "heretical" thoughts (i.e. against Ingsoc's principles) impossible as they cannot be expressed.[citation needed]The idea that a language's structure can be used to influence thought is known aslinguistic relativity.

Whether or not the Newspeak appendix implies a hopeful end toNineteen Eighty-Fourremains a critical debate. Many claim that it does, citing the fact that it is in standard English and is written in thepast tense:"Relative to our own, the Newspeak vocabulary was tiny, and new ways of reducing it were constantly being devised" (p. 422). Some critics (Atwood,[48]Benstead,[49]Milner,[50]Pynchon[51]) claim that for Orwell, Newspeak and the totalitarian governments are all in the past.

Thoughtcrime

[edit]Thoughtcrime describes a person's politically unorthodox thoughts, such as unspoken beliefs and doubts that contradict the tenets ofIngsoc(English Socialism), the dominant ideology of Oceania. In the official language of Newspeak, the wordcrimethinkdescribes the intellectual actions of a person who entertains and holds politically unacceptable thoughts; thus the government of the Party controls the speech, the actions, and the thoughts of the citizens of Oceania.[52]In contemporary English usage, the wordthoughtcrimedescribes beliefs that are contrary to accepted norms of society, and is used to describe theological concepts, such as disbelief andidolatry,[53]and the rejection of anideology.[54]

Themes

[edit]Nationalism

[edit]Nineteen Eighty-Fourexpands upon the subjects summarised in Orwell's essay "Notes on Nationalism"[55]about the lack of vocabulary needed to explain the unrecognised phenomena behind certain political forces. InNineteen Eighty-Four,the Party's artificial, minimalist language 'Newspeak' addresses the matter.

- Positive nationalism: For instance, Oceanians' perpetual love for Big Brother. Orwell argues in the essay that ideologies such asNeo-ToryismandCeltic nationalismare defined by their obsessive sense of loyalty to some entity.

- Negative nationalism: For instance, Oceanians' perpetual hatred for Emmanuel Goldstein. Orwell argues in the essay that ideologies such asTrotskyismandAntisemitismare defined by their obsessive hatred of some entity.

- Transferred nationalism: For instance, when Oceania's enemy changes, an orator makes a change mid-sentence, and the crowd instantly transfers its hatred to the new enemy. Orwell argues that ideologies such asStalinism[56]and redirected feelings of racial animus and class superiority among wealthy intellectuals exemplify this. Transferred nationalism swiftly redirects emotions from one power unit to another. In the novel, it happens during Hate Week, a Party rally against the original enemy. The crowd goes wild and destroys the posters that are now against their new friend, and many say that they must be the act of an agent of their new enemy and former friend. Many of the crowd must have put up the posters before the rally but think that the state of affairs had always been the case.

O'Brien concludes: "The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power."[57]

Futurology

[edit]In the book, Inner Party member O'Brien describes the Party's vision of the future:

There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always—do not forget this, Winston—always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.

— Part III, chapter III,Nineteen Eighty-Four

Censorship

[edit]One of the most notable themes inNineteen Eighty-Fouriscensorship,especially in the Ministry of Truth, where photographs and public archives are manipulated to rid them of "unpersons" (people who have been erased from history by the Party).[58]On the telescreens, almost all figures of production are grossly exaggerated or simply fabricated to indicate an ever-growing economy, even during times when the reality is the opposite. One small example of the endless censorship is Winston being charged with the task of eliminating a reference to an unperson in a newspaper article. He also proceeds to write an article about Comrade Ogilvy, a made-up party member who allegedly "displayed great heroism by leaping into the sea from a helicopter so that the dispatches he was carrying would not fall into enemy hands."[59]

Surveillance

[edit]In Oceania, the upper and middle classes have very little true privacy. All of their houses and apartments are equipped with two-way telescreens so that they may be watched or listened to at any time. Similar telescreens are found at workstations and in public places, along with hidden microphones. Written correspondence is routinely opened and read by the government before it is delivered. The Thought Police employ undercover agents, who pose as normal citizens and report any person with subversive tendencies. Children are encouraged to report suspicious persons to the government, and some denounce their parents. Citizens are controlled, and the smallest sign of rebellion, even something as small as a suspicious facial expression, can result in immediate arrest and imprisonment. Thus, citizens are compelled to obedience.

Poverty and inequality

[edit]According to Orwell's book, almost the entire world lives in poverty; hunger, thirst, disease, and filth are the norms. Ruined cities and towns are common: the consequence of perpetual wars and extreme economic inefficiency. Social decay and wrecked buildings surround Winston; aside from the ministries' headquarters, little of London was rebuilt. Middle class citizens and proles consume synthetic foodstuffs and poor-quality "luxuries" such as oily gin and loosely-packed cigarettes, distributed under the "Victory" brand, a parody of the low-quality Indian-made "Victory" cigarettes, which British soldiers commonly smoked during World War II.

Winston describes something as simple as the repair of a broken window as requiring committee approval that can take several years and so most of those living in one of the blocks usually do the repairs themselves (Winston himself is called in by Mrs. Parsons to repair her blocked sink). All upper-class and middle-class residences include telescreens that serve both as outlets for propaganda and surveillance devices that allow the Thought Police to monitor them; they can be turned down, but the ones in middle-class residences cannot be turned off.

In contrast to their subordinates, the upper class of Oceanian society reside in clean and comfortable flats in their own quarters, with pantries well-stocked with foodstuffs such as wine, real coffee, real tea, real milk, and real sugar, all denied to the general populace.[60]Winston is astonished that theliftsin O'Brien's building work, the telescreens can be completely turned off, and O'Brien has an Asian manservant, Martin. All upper class citizens are attended to by slaves captured in the "disputed zone", and "The Book" suggests that many have their own cars or even helicopters.

However, despite their insulation and overt privileges, the upper class are still not exempt from the government's brutal restriction of thought and behaviour, even while lies and propaganda apparently originate from their own ranks. Instead, the Oceanian government offers the upper class their "luxuries" in exchange for them maintaining their loyalty to the state; non-conformant upper-class citizens can still be condemned, tortured, and executed just like any other individual. "The Book" makes clear that the upper class' living conditions are only "relatively" comfortable, and would be regarded as "austere" by those of the pre-revolutionary élite.[61]

The proles live in poverty and are kept sedated with pornography, a national lottery whose big prizes are reported won by non-existent people, and gin, "which the proles were not supposed to drink". At the same time, the proles are freer and less intimidated than the upper classes: they are not expected to be particularly patriotic and the levels of surveillance that they are subjected to are very low; they lack telescreens in their own homes. "The Book" indicates that because the middle class, not the lower class, traditionally starts revolutions, the model demands tight control of the middle class, with ambitious Outer-Party members neutralised via promotion to the Inner Party or "reintegration"[clarification needed]by the Ministry of Love, and proles can be allowed intellectual freedom because they are deemed to lack intellect. Winston nonetheless believes that "the future belonged to the proles".[62]

The standard of living of the populace is extremely low overall.[63]Consumer goods are scarce, and those available through official channels are of low quality; for instance, despite the Party regularly reporting increased boot production, more than half of the Oceanian populace goes barefoot.[64]The Party claims that poverty is a necessary sacrifice for the war effort, and "The Book" confirms that to be partially correct since the purpose of perpetual war is to consume surplus industrial production.[65]As "The Book" explains, society is in fact designed to remain on the brink of starvation, as "In the long run, a hierarchical society was only possible on a basis of poverty and ignorance."

Sources for literary motifs

[edit]Nineteen Eighty-Fouruses themes from life in the Soviet Union and wartime life in Great Britain as sources for many of its motifs. Some time at an unspecified date after the first American publication of the book, producerSidney Sheldonwrote to Orwell interested in adapting the novel to the Broadway stage. Orwell wrote in a letter to Sheldon (to whom he would sell the US stage rights) that his basic goal withNineteen Eighty-Fourwas imagining the consequences of Stalinist government ruling British society:

[Nineteen Eighty-Four] was based chiefly on communism, because that is the dominant form of totalitarianism, but I was trying chiefly to imagine what communism would be like if it were firmly rooted in the English speaking countries, and was no longer a mere extension of theRussian Foreign Office.[66]

According to Orwell biographerD. J. Taylor,the author'sA Clergyman's Daughter(1935) has "essentially the same plot ofNineteen Eighty-Four... It's about somebody who is spied upon, and eavesdropped upon, and oppressed by vast exterior forces they can do nothing about. It makes an attempt at rebellion and then has to compromise ".[67]

The statement "2 + 2 = 5",used to torment Winston Smith during his interrogation, was a communist party slogan from the secondfive-year plan,which encouraged fulfilment of the five-year plan in four years. The slogan was seen in electric lights on Moscow house-fronts, billboards and elsewhere.[68]

The switch of Oceania's allegiance from Eastasia to Eurasia and the subsequent rewriting of history ( "Oceania was at war with Eastasia: Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia. A large part of the political literature of five years was now completely obsolete"; ch 9) is evocative of the Soviet Union's changing relations with Nazi Germany. The two nations were open and frequently vehement critics of each other until the signing of the 1939Treaty of Non-Aggression.Thereafter, and continuing until the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, no criticism of Germany was allowed in the Soviet press, and all references to prior party lines stopped—including in the majority of non-Russian communist parties who tended to follow the Russian line. Orwell had criticised theCommunist Party of Great Britainfor supporting the Treaty in his essays forBetrayal of the Left(1941). "The Hitler-Stalin pact of August 1939 reversed the Soviet Union's stated foreign policy. It was too much for many of thefellow-travellerslikeGollancz[Orwell's sometime publisher] who had put their faith in a strategy of constructionPopular Frontgovernments and the peace bloc between Russia, Britain and France. "[69]

The description of Emmanuel Goldstein, with a "small, goatee beard", evokes the image ofLeon Trotsky.The film of Goldstein during the Two Minutes Hate is described as showing him being transformed into a bleating sheep. This image was used in a propaganda film during theKino-eyeperiod of Soviet film, which showed Trotsky transforming into a goat.[70][page needed]Like Goldstein, Trotsky was a formerly high-ranking party official who was ostracized and then wrote a book criticizing party rule,The Revolution Betrayed,published in 1936.

The omnipresent images of Big Brother, a man described as having a moustache, bears resemblance to the cult of personality built up aroundJoseph Stalin. [71]

The news in Oceania emphasised production figures, just as it did in the Soviet Union, where record-setting in factories (by "Heroes of Socialist Labour") was especially glorified. The best known of these wasAlexei Stakhanov,who purportedly set a record for coal mining in 1935.[72]

The tortures of the Ministry of Love evoke the procedures used by theNKVDin their interrogations,[73][page needed]including the use of rubber truncheons, being forbidden to put your hands in your pockets, remaining in brightly lit rooms for days, torture through the use of their greatest fear, and the victim being shown a mirror after their physical collapse.[citation needed]

The random bombing of Airstrip One is based on thearea bombingof London byBuzz bombsand theV-2 rocketin 1944–1945.[71]

TheThought Policeis based on theNKVD,which arrested people for random "anti-soviet" remarks.[74][page needed]

The confessions of the "Thought Criminals" Rutherford, Aaronson, and Jones are based on theshow trialsof the 1930s, which included fabricated confessions by prominent BolsheviksNikolai Bukharin,Grigory ZinovievandLev Kamenevto the effect that they were being paid by the Nazi government to undermine the Soviet regime underLeon Trotsky's direction.[75]

The song "Under the Spreading Chestnut Tree"(" Under the spreading chestnut tree, I sold you, and you sold me ") was based on an old English song called" Go no more a-rushing "(" Under the spreading chestnut tree, Where I knelt upon my knee, We were as happy as could be, 'Neath the spreading chestnut tree. "). The song was published as early as 1891. The song was a popular camp song in the 1920s, sung with corresponding movements (like touching one's chest when singing" chest ", and touching one's head when singing" nut ").Glenn Millerrecorded the song in 1939.[76]

The "Hates" (Two Minutes Hate and Hate Week) were inspired by the constant rallies sponsored by party organs throughout the Stalinist period. These were often short pep-talks given to workers before their shifts began (Two Minutes Hate),[77]but could also last for days, as in the annual celebrations of the anniversary of theOctober Revolution(Hate Week).

Orwell fictionalised "newspeak", "doublethink", and "Ministry of Truth" based on both the Soviet press, and British wartime usage, such as "Miniform".[78]In particular, he adapted Soviet ideological discourse constructed to ensure that public statements could not be questioned.[79]

Winston Smith's job, "revising history" (and the "unperson" motif) are based oncensorship of images in the Soviet Union,which airbrushed images of "fallen" people from group photographs and removed references to them in books and newspapers.[81]In one well-known example, the second edition of theGreat Soviet Encyclopediahad an article aboutLavrentiy Beria.After his fall from power and execution, subscribers received a letter from the editor[82]instructing them to cut out and destroy the three-page article on Beria and paste in its place enclosed replacement pages expanding the adjacent articles onF. W. Bergholz(an 18th-century courtier), theBering Sea,andBishop Berkeley.[83][84][85]

Big Brother's "Orders of the Day" were inspired by Stalin's regular wartime orders, called by the same name. A small collection of the more political of these have been published (together with his wartime speeches) in English asOn the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Unionby Joseph Stalin.[86][87]Like Big Brother's Orders of the day, Stalin's frequently lauded heroic individuals,[86]like Comrade Ogilvy, the fictitious hero Winston Smith invented to "rectify" (fabricate) a Big Brother Order of the day.

The Ingsoc slogan "Our new, happy life", repeated from telescreens, evokes Stalin's 1935 statement, which became aCPSUslogan, "Life has become better, Comrades; life has become more cheerful."[74]

In 1940, Argentine writerJorge Luis Borgespublished "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius",which describes the invention by a" benevolent secret society "of a world that would seek to remake human language and reality along human-invented lines. The story concludes with an appendix describing the success of the project. Borges' story addresses similar themes ofepistemology,language and history to 1984.[88]

DuringWorld War II,Orwell believed thatBritish democracyas it existed before 1939 would not survive the war. The question being "Would it end via Fascistcoup d'étatfrom above or via Socialist revolution from below? "[89]Later, he admitted that events proved him wrong: "What really matters is that I fell into the trap of assuming that 'the war and the revolution are inseparable'."[90]

Nineteen Eighty-Four(1949) andAnimal Farm(1945) share themes of the betrayed revolution, the individual's subordination to the collective, rigorously enforced class distinctions (Inner Party, Outer Party, proles), thecult of personality,concentration camps,Thought Police,compulsory regimented daily exercise, and youth leagues.Oceaniaresulted from the US annexation of the British Empire to counter the Asian peril to Australia and New Zealand. It is a naval power whose militarism venerates the sailors of the floating fortresses, from which battle is given to recapturing India, the "Jewel in the Crown" of the British Empire. Much of Oceanic society is based upon the USSR underJoseph Stalin—Big Brother.The televisedTwo Minutes Hateis ritual demonisation of theenemies of the State,especiallyEmmanuel Goldstein(vizLeon Trotsky). Altered photographs and newspaper articles createunpersonsdeleted from the national historical record, including even founding members of the regime (Jones, Aaronson, and Rutherford) in the 1960s purges (viztheSoviet Purgesof the 1930s, in whichleaders of the Bolshevik Revolutionweresimilarly treated). A similar thing also happened during theFrench Revolution'sReign of Terrorin which many of the original leaders of the Revolution were later put to death, for exampleDantonwho was put to death byRobespierre,and then later Robespierre himself met the same fate.[citation needed]

In his 1946 essay "Why I Write",Orwell explains that the serious works he wrote since theSpanish Civil War(1936–39) were "written, directly or indirectly, againsttotalitarianismand fordemocratic socialism".[4][91]Nineteen Eighty-Fouris acautionary taleabout revolution betrayed by totalitarian defenders previously proposed inHomage to Catalonia(1938) andAnimal Farm(1945), whileComing Up for Air(1939) celebrates the personal and political freedoms lost inNineteen Eighty-Four(1949). BiographerMichael Sheldennotes Orwell'sEdwardianchildhood atHenley-on-Thamesas the golden country; being bullied atSt Cyprian's Schoolas his empathy with victims; his life in theIndian Imperial Policein Burma and the techniques of violence and censorship in theBBCas capricious authority.[92]

Other influences includeDarkness at Noon(1940) andThe Yogi and the Commissar(1945) byArthur Koestler;The Iron Heel(1908) byJack London;1920: Dips into the Near Future[93]byJohn A. Hobson;Brave New World(1932) byAldous Huxley;We(1921) by Yevgeny Zamyatin which he reviewed in 1946;[94]andThe Managerial Revolution(1940) byJames Burnhampredicting perpetual war among three totalitarian superstates. Orwell toldJacintha Buddicomthat he would write a novel stylistically likeA Modern Utopia(1905) byH. G. Wells.[95]

Extrapolating from World War II, the novel'spasticheparallels the politics and rhetoric at war's end—the changed alliances at the "Cold War's "(1945–91) beginning; theMinistry of Truthderives from the BBC's overseas service, controlled by theMinistry of Information;Room 101derives from a conference room at BBCBroadcasting House;[96]theSenate Houseof the University of London, containing the Ministry of Information is the architectural inspiration for the Minitrue; the post-war decrepitude derives from the socio-political life of the UK and the US, i.e., the impoverished Britain of 1948 losing its Empire despite newspaper-reported imperial triumph; and war ally but peace-time foe, Soviet Russia becameEurasia.[citation needed]

The term "English Socialism" has precedents in Orwell's wartime writings; in the essay "The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius"(1941), he said that" the war and the revolution are inseparable... the fact that we are at war has turned Socialism from a textbook word into a realisable policy "—because Britain's superannuated social class system hindered the war effort and only a socialist economy would defeatAdolf Hitler.Given the middle class's grasping this, they too would abide socialist revolution and that only reactionary Britons would oppose it, thus limiting the force revolutionaries would need to take power. An English Socialism would come about which "will never lose touch with the tradition of compromise and the belief in a law that is above the State. It will shoot traitors, but it will give them a solemn trial beforehand and occasionally it will acquit them. It will crush any open revolt promptly and cruelly, but it will interfere very little with the spoken and written word."[97]

In the world ofNineteen Eighty-Four,"English Socialism" (or "Ingsoc"inNewspeak) is atotalitarianideology unlike the English revolution he foresaw. Comparison of the wartime essay "The Lion and the Unicorn" withNineteen Eighty-Fourshows that he perceived a Big Brother regime as a perversion of his cherished socialist ideals and English Socialism. Thus Oceania is a corruption of the British Empire he believed would evolve "into a federation of Socialist states, like a looser and freer version of the Union of Soviet Republics".[98][verification needed]

Critical reception

[edit]When it was first published,Nineteen Eighty-Fourreceived critical acclaim.V. S. Pritchett,reviewing the novel for theNew Statesmanstated: "I do not think I have ever read a novel more frightening and depressing; and yet, such are the originality, the suspense, the speed of writing and withering indignation that it is impossible to put the book down."[99]P. H. Newby,reviewingNineteen Eighty-FourforThe Listenermagazine, described it as "the most arresting political novel written by an Englishman sinceRex Warner'sThe Aerodrome."[100]Nineteen Eighty-Fourwas also praised byBertrand Russell,E. M. ForsterandHarold Nicolson.[100]On the other hand,Edward Shanks,reviewingNineteen Eighty-FourforThe Sunday Times,was dismissive; Shanks claimedNineteen Eighty-Four"breaks all records for gloomy vaticination".[100]C. S. Lewiswas also critical of the novel, claiming that the relationship of Julia and Winston, and especially the Party's view on sex, lacked credibility, and that the setting was "odious rather than tragic".[101]HistorianIsaac Deutscherwas far more critical of Orwell from aMarxistperspective and characterised him as a “simple mindedanarchist”.Deutscher argued that Orwell had struggled to comprehend the dialectical philosophy of Marxism, demonstrated personal ambivalence towardsother strands of socialismand his work,1984,had been appropriated for the purpose ofanti-communistCold Warpropaganda.[102][103]

On its publication, many American reviewers interpreted the book as a statement on BritishPrime MinisterClement Attlee'ssocialist policies, or the policies of Joseph Stalin.[104]Serving as prime minister from 1945 to 1951, Attlee implemented wide-ranging social reforms and changes in the British economy following World War II. American trade union leader Francis A. Hanson wanted to recommend the book to his members but was concerned with some of the reviews it had received, so Orwell wrote a letter to him.[105][104]In his letter, Orwell described his book as a satire, and said:

I do not believe that the kind of society I describe will necessarily arrive, but I believe (allowing, of course, for the fact that the book is a satire) that something resembling it could arrive...[it is] a show...[of the] perversions to which a centralised economy is liable and which have already been partly realisable in communism and fascism.

— George Orwell, Letter to Francis A. Hanson

Throughout its publication history,Nineteen Eighty-Fourhas been either banned or legallychallengedas subversive or ideologically corrupting, like the dystopian novelsWe(1924) byYevgeny Zamyatin,Brave New World(1932) byAldous Huxley,Darkness at Noon(1940) byArthur Koestler,Kallocain(1940) byKarin Boye,andFahrenheit 451(1953) byRay Bradbury.[106]

On 5 November 2019, theBBCnamedNineteen Eighty-Fouron its list of the100 most influential novels.[107]

According toCzesław Miłosz,adefectorfromStalinist Poland,the book also made an impression behind theIron Curtain.Writing inThe Captive Mind,he stated "[a] few have become acquainted with Orwell's1984;because it is both difficult to obtain and dangerous to possess, it is known only to certain members of the Inner Party. Orwell fascinates them through his insight into details they know well... Even those who know Orwell only by hearsay are amazed that a writer who never lived in Russia should have so keen a perception into its life. "[108][109]WriterChristopher Hitchenshas called this "one of the greatest compliments that one writer has ever bestowed upon another... Only one or two years after Orwell's death, in other words, his book about a secret book circulated only within the Inner Party was itself a secret book circulated only within the Inner Party."[108]: 54–55

Adaptations in other media

[edit]In the same year as the novel's publishing, a one-hour radio adaptation was aired on the United States'NBCradio network as part of theNBC University Theatreseries. Thefirst television adaptationappeared as part ofCBS'sStudio Oneseries in September 1953.[110]BBC Televisionbroadcastan adaptationbyNigel Knealein December 1954. The first feature film adaptation,1984,was released in 1956. A second feature-length adaptation,Nineteen Eighty-Four,followed in 1984, a reasonably faithful adaptation of the novel. The story has been adapted several other times to radio, television, and film; other media adaptations include theater (a musical[111]and aplay),opera,and ballet.[112]An audio dramatization of the novel was released in 2024 to critical acclaim, starringAndrew Garfieldas Winston.

Translations

[edit]

The novel was banned in the Soviet Union until 1988, when the first publicly available Russian version in the country, translated by Vyacheslav Nedoshivin, was published inKodry,a literary journal of Soviet Moldavia. In 1989, another Russian version, translated byViktor Golyshev,was also published. Outside the Soviet Union, the first Russian version was serialised in the emigre magazineGraniin the mid-1950s, then published as a book in 1957 in Frankfurt. Another Russian version, translated by Sergei Tolstoy from French version, was published in Rome in 1966. These translations were smuggled into the Soviet Union, which became quite popular among dissidents.[113]Some underground published translations also appeared in the Soviet Union, for example, Soviet philosopherEvald Ilyenkovtranslated the novel from German version into a Russian version.[114]

For Soviet elite, as early as 1959, according to the order of the Ideological Department of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party, the Foreign Literature Publishers secretly issued a Russian version of the novel, for the senior officers of the Communist Party.[115]

In the People's Republic of China, the firstSimplified Chineseversion, translated byDong Leshan,was serialised in the periodicalSelected Translations from Foreign Literaturein 1979, for senior officials and intellectuals deemed politically reliable enough. In 1985, the Chinese version was published by Huacheng Publishing House, as a restricted publication. It was first available to the general public in 1988, by the same publisher.[116]Amy Hawkins and Jeffrey Wasserstrom ofThe Atlanticstated in 2019 that the book is widely available in mainland China for several reasons: the general public by and large no longer reads books; because the elites who do read books feel connected to the ruling party anyway; and because the Communist Party sees being too aggressive in blocking cultural products as a liability. The authors stated "It was—and remains—as easy to buy1984andAnimal FarminShenzhenorShanghaias it is in London or Los Angeles. "[117]They also stated that "The assumption is not that Chinese people can't figure out the meaning of 1984, but that the small number of people who will bother to read it won't pose much of a threat."[117]British journalist Michael Rank argued that it is only because the novel is set in London and written by a foreigner that the Chinese authorities believe it has nothing to do with China.[116]

By 1989,Nineteen Eighty-Fourhad been translated into 65 languages, more than any other novel in English at that time.[118]

Cultural impact

[edit]

The effect ofNineteen Eighty-Fouron the English language is extensive; the concepts ofBig Brother,Room 101,theThought Police,thoughtcrime,unperson,memory hole(oblivion),doublethink(simultaneously holding and believing contradictory beliefs) andNewspeak(ideological language) have become common phrases for denoting totalitarian authority.Doublespeakandgroupthinkare both deliberate elaborations ofdoublethink,and the adjective "Orwellian" means similar to Orwell's writings, especiallyNineteen Eighty-Four.The practice of ending words with"-speak"(such asmediaspeak) is drawn from the novel.[119]Orwell is perpetually associated with 1984; in July 1984,an asteroidwas discovered byAntonín Mrkosand named after Orwell.

References to the themes, concepts and plot ofNineteen Eighty-Fourhave appeared frequently in other works, especially in popular music and video entertainment. An example is the worldwide hit reality television showBig Brother,in which a group of people live together in a large house, isolated from the outside world but continuously watched by television cameras.

In November 2012, theUnited States governmentargued before theUS Supreme Courtthat it could continue toutilize GPS tracking of individualswithout first seeking a warrant. In response, JusticeStephen Breyerquestioned what that means for a democratic society by referencingNineteen Eighty-Four,stating "If you win this case, then there is nothing to prevent the police or the government from monitoring 24 hours a day the public movement of every citizen of the United States. So if you win, you suddenly produce what sounds like Nineteen Eighty-Four..."[120]

The book touches on the invasion of privacy and ubiquitous surveillance. From mid-2013 it was publicised that theNSAhas been secretly monitoring and storing global internet traffic, including the bulk data collection of email and phone call data. Sales ofNineteen Eighty-Fourincreased by up to seven times within the first week of the2013 mass surveillance leaks.[121][122][123]The book again topped the Amazon.com sales charts in 2017 after a controversy involvingKellyanne Conwayusing the phrase "alternative facts"to explain discrepancies with the media.[124][125][126][127]

Nineteen Eighty-Fourwas number three on the list of "Top Check Outs Of All Time" by theNew York Public Library.[128]

Nineteen Eighty-Fourenteredthe public domain on 1 January 2021,70 years after Orwell's death, in most of the world. It is still under copyright in the US until 95 years after publication, or 2044.[129][130]

Brave New Worldcomparisons

[edit]In October 1949, after readingNineteen Eighty-Four,Huxley sent a letter to Orwell in which he argued that it would be more efficient for rulers to stay in power by the softer touch by allowing citizens to seek pleasure to control them rather than use brute force. He wrote:

Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World.

...

Within the next generation I believe that the world's rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience.[131]

In the decades since the publication ofNineteen Eighty-Four,there have been numerous comparisons to Huxley'sBrave New World,which had been published 17 years earlier, in 1932.[132][133][134][135]They are both predictions of societies dominated by a central government and are both based on extensions of the trends of their times. However, members of the ruling class ofNineteen Eighty-Fouruse brutal force, torture and harshmind controlto keep individuals in line, while rulers inBrave New Worldkeep the citizens in line by drugs, hypnosis, genetic conditioning and pleasurable distractions. Regarding censorship, inNineteen Eighty-Fourthe government tightly controls information to keep the population in line, but in Huxley's world, so much information is published that readers are easily distracted and overlook the information that is relevant.[136]

Elements of both novels can be seen in modern-day societies, with Huxley's vision being more dominant in the West and Orwell's vision more prevalent with dictatorships, including those in communist countries (such as in modern-dayChinaandNorth Korea), as is pointed out in essays that compare the two novels, including Huxley's ownBrave New World Revisited.[137][138][139][127]

Comparisons with later dystopian novels likeThe Handmaid's Tale,Virtual Light,The Private EyeandThe Children of Menhave also been drawn.[140][141]

In popular culture

[edit]- In 1955, an episode of BBC'sThe Goon Show,1985,was broadcast, written bySpike MilliganandEric Sykesand based onNigel Kneale'stelevision adaptation.It was re-recorded about a month later with the same script but a slightly different cast.[142]1985parodies many of the main scenes in Orwell's novel.

- In 1970, the American rock groupSpiritreleased the song "1984" based on Orwell's novel.

- In 1973, ex-Soft MachinebassistHugh Hopperreleased an album called1984on the Columbia label (UK), consisting of instrumentals with Orwellian titles such as "Miniluv", "Minipax", "Minitrue", and so forth.

- In 1974,David Bowiereleased the albumDiamond Dogs,which is thought to be loosely based on the novelNineteen Eighty-Four.It includes the tracks "We Are The Dead","1984 "and" Big Brother ". Before the album was made, Bowie's management (MainMan) had planned for Bowie and Tony Ingrassia (MainMan's creative consultant) to co-write and direct a musical production of Orwell'sNineteen Eighty-Four,but Orwell's widow refused to give MainMan the rights.[143][144]

- In 1977, the British rock bandThe Jamreleased the albumThis Is the Modern World,which includes the track "Standards" byPaul Weller.This track concludes with the lyrics "...and ignorance is strength, we have God on our side, look, you know what happened to Winston."[145]

- In 1984,Ridley Scottdirected a television commercial, "1984",to launchApple'sMacintoshcomputer.[146]The advert stated, "1984 won't be like1984",suggesting that the Apple Mac would be freedom from Big Brother, i.e., the IBM PC.[147]

- Rage Against The Machine's 2000 single, "Testify",from their albumThe Battle of Los Angeles,features the use of "The Party" slogan, "Who controls the past(now), controls the future. Who controls the present(now), controls the past."[145]

- An episode ofDoctor Who,called "The God Complex",depicts an alien ship disguised as a hotel containing Room 101-like spaces, and also, like the novel, quotes the nursery rhyme"Oranges and Lemons".[148]

- The two part episodeChain of CommandonStar Trek: The Next Generationbears some resemblances to the novel.[149]

- Radiohead's 2003 single "2 + 2 = 5",from their albumHail to the Thief,is Orwellian by title and content.Thom Yorkestates, "I was listening to a lot of political programs onBBC Radio 4.I found myself writing down little nonsense phrases, those Orwellian euphemisms that [the British and American governments] are so fond of. They became the background of the record. "[145]

- In September 2009, the English progressive rock bandMusereleasedThe Resistance,which included songs influenced byNineteen Eighty-Four.[150]

- InMarilyn Manson's autobiographyThe Long Hard Road Out of Hell,he states: "I was thoroughly terrified by the idea of the end of the world and the Antichrist. So I became obsessed with it... reading prophetic books like... 1984 by George Orwell..."[151]

- English bandBastillereferences the novel in their song "Back to the Future", the fifth track on their 2022 albumGive Me the Future,in the opening lyrics: "Feels like we danced into a nightmare/We're living 1984/If doublethink's no longer fiction/We'll dream of Huxley's Island shores."[152]

- Released in 2004, KAKU P-Model/Susumu Hirasawa's song Big Brother directly references 1984, and the album itself is about a fictional dystopia in a distant future.

- The Usedreleased a song by the same name, "1984", on their 2020 albumHeartwork.[153]

See also

[edit]- Authoritarian personality

- Brainwashing

- Closed-circuit television(CCTV)

- Culture of fear

- Fahrenheit 451,a similar novel revolving around censorship

- Ideocracy

- Language and thought

- List of stories set in a future now in the past

- Mass surveillance

- New World Order (conspiracy theory)

- Psychological projection

- Scapegoating

- Totalitarianism

- Utopian and dystopian fiction

- V for Vendetta,a similar graphic novel andfilm

- We,a similar novel

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^"Nineteen Eighty-Four".knowthyshelf.com.13 August 2015.Retrieved11 February2024.

- ^"Classify".OCLC. Archived fromthe originalon 2 February 2019.Retrieved22 May2017.

- ^Murphy, Bruce (1996).Benét's reader's encyclopedia.New York: Harper Collins. p.734.ISBN978-0-06-181088-6.OCLC35572906.

- ^abAaronovitch, David (8 February 2013)."1984: George Orwell's road to dystopia".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 24 January 2018.Retrieved8 February2013.

- ^Lynskey, Dorian (10 June 2019)."George Orwell's 1984: Why it still matters".BBC News.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2023.Retrieved7 October2023– via YouTube.

- ^Chernow, Barbara; Vallasi, George (1993).The Columbia Encyclopedia(5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 2030.OCLC334011745.

- ^Crouch, Ian (11 June 2013)."So Are We Living in 1984?".The New Yorker.Archivedfrom the original on 10 September 2023.Retrieved3 December2019.

- ^Seaton, Jean."Why Orwell's 1984 could be about now".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2020.Retrieved3 December2019.

- ^Leetaru, Kalev."As Orwell's 1984 Turns 70 It Predicted Much of Today's Surveillance Society".Forbes.Archivedfrom the original on 27 March 2023.Retrieved3 December2019.

- ^ab"The savage satire of '1984' still speaks to us today".The Independent.7 June 1999. Archived fromthe originalon 7 January 2023.Retrieved7 January2023.

Orwell said that his book was a satire – a warning certainly, but in the form of satire.

- ^Grossman, Lev (8 January 2010)."Is1984one of the All-TIME 100 Best Novels? ".Time.Archivedfrom the original on 20 August 2017.Retrieved29 December2022.

- ^"100 Best Novels « Modern Library".www.modernlibrary.com.Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2010.Retrieved29 December2022.

- ^"BBC – The Big Read – Top 100 Books".BBC.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2012.Retrieved29 December2022.

- ^ab"Orwell's Notes on 1984: Mapping the Inspiration of a Modern Classic".Literary Hub.18 October 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 1 January 2023.Retrieved1 January2023.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 329.

- ^"Reporting from the Ruins".The Orwell Society.3 October 2021.Archivedfrom the original on 26 March 2023.Retrieved3 April2023.

- ^abLynskey 2019,ch. 6: "The Heretic"

- ^abBowker 2003,p. 330.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 334.

- ^abcLynskey 2019,ch. 7: "Inconvenient Facts"

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 336.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 337.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 346.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 319.

- ^Bowker 2003,pp. 353, 357.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 370.

- ^abcdLynskey 2019,ch. 8: "Every Book Is a Failure"

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 373.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 374.

- ^Orwell, George(1968).Orwell, Sonia;Angus, Ian(eds.).The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell Vol. IV: In Front Of Your Nose 1945-1950.New York:Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.p. 448.Retrieved19 May2024– viaInternet Archive.

- ^Crick, Bernard. Introduction toNineteen Eighty-Four(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984)

- ^Orwell 2003a,p. x.

- ^abcdeLynskey 2019,ch. 9: "The Clocks Strike Thirteen"

- ^Shelden 1991,p. 470.

- ^Bowker 2003,pp. 383, 399.

- ^"Charles' George Orwell Links".Netcharles.com. Archived fromthe originalon 18 July 2011.Retrieved4 July2011.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 399.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 401.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 411.

- ^Bowker 2003,p. 426.

- ^"Brown library buys singer Janis Ian's collection of fantasy, science fiction".providencejournal.com.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2019.Retrieved24 September2019.

- ^Braga, Jennifer (10 June 2019)."Announcement | 70th Anniversary of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four".Brown University Library News.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2019.Retrieved24 September2019.

- ^Martyris, Nina (18 September 2014)."George Orwell Weighs in on Scottish Independence".LA Review of Books.Archivedfrom the original on 28 October 2017.Retrieved20 October2017.

- ^This may be a reference to "McAndrew's Hymn",which includes the lines" From coupler-flange to spindle-guide I see Thy Hand, O God— / Predestination in the stride o' yon connectin'-rod ".[43]

- ^abPart II, Ch. 9.

- ^University of Toronto Quarterly, Volume 26.University of Toronto Press. 1957. p. 89.

- ^"Definition of BIG BROTHER".www.merriam-webster.com.11 October 2023.Archivedfrom the original on 30 April 2017.Retrieved20 October2023.

- ^Atwood, Margaret(16 June 2003)."Orwell and me".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2022.Retrieved29 December2022.

- ^Benstead, James (26 June 2005)."Hope Begins in the Dark: Re-readingNineteen Eighty-Four"Archived24 October 2005 at theWayback Machine.

- ^Andrew Milner(2012).Locating Science Fiction.Oxford University Press. pp. 120–135.ISBN9781846318429.

- ^Orwell 2003b,pp. vii–xxviThomas Pynchon's foreword in shortened form published also as"The Road to1984"Archived15 May 2007 at theWayback MachineinThe Guardian(David Kipen(3 May 2003)."Pynchon brings added currency toNineteen Eighty-Four".SFGATE.Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2023.Retrieved9 September2023.)

- ^Orwell, George; Rovere, Richard Halworth (1984) [1956],The Orwell Reader: Fiction, Essays, and Reportage,San Diego: Harcourt, Brace, p.409,ISBN978-0-15-670176-1.

- ^Lewis, David.Papers in Ethics and Social Philosophy(2000), Volume 3, p. 107.

- ^Glasby, John.Evidence, Policy and Practice: Critical Perspectives in Health and Social Care(2011), p. 22.

- ^"George Orwell:" Notes on Nationalism "".Resort.com. May 1945.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2019.Retrieved25 March2010.

- ^Decker, James (2004)."George Orwell's 1984 and Political Ideology".Ideology.p.146.doi:10.1007/978-0-230-62914-1_7.ISBN978-0-333-77538-7.