Midland American English

Midland American Englishis a regionaldialector super-dialect ofAmerican English,[2]geographically lying between the traditionally-definedNorthernandSouthern United States.[3]The boundaries of Midland American English are not entirely clear, being revised and reduced by linguists due to definitional changes and several Midland sub-regions undergoing rapid and diverging pronunciation shifts since the early-middle 20th century onwards.[4][5]

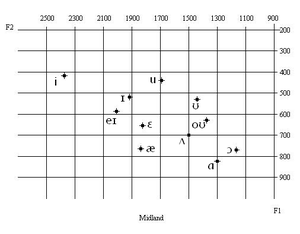

As of theearly 21st century,these general characteristics of the Midland regional accent are firmly established:frontingof the/oʊ/,/aʊ/,and/ʌ/vowels occurs towards the center or even the front of the mouth;[6]thecot–caught mergeris neither fully completed nor fully absent; andshort-atensingevidently occurs strongest beforenasal consonants.[7]The currently-documented core of the Midland dialect region spans from centralOhioat its eastern extreme to centralNebraskaandOklahoma Cityat its western extreme. Certain areas outside the core also clearly demonstrate a Midland accent, includingCharleston, South Carolina;[8]the Texan cities ofAbilene,Austin,andCorpus Christi;and central and some areas of southernFlorida.[9]

Early 20th-century dialectology was the first to identify the "Midland" as a regionlexicallydistinct from the North and the South and later even focused on an internal division: North Midland versus South Midland. However, 21st-century studies now reveal increasing unification of the South Midland with a larger mid-20th-centurySouthern accent region,while much of the North Midland retains a more "General American"accent.[10][11]

Early 20th-century boundaries established for the Midland dialect region are being reduced or revised since several previous subregions of Midland speech have since developed their own distinct dialects.Pennsylvania,the original home state of the Midland dialect, is one such area and has now formed such unique dialects asPhiladelphiaandPittsburgh English.[12]

Original and former Midland

[edit]The dialect region "Midland" was first labeled in the 1890s,[13]but only first defined (tentatively) byHans Kurathin 1949 as centered on central Pennsylvania and expanding westward and southward to include most ofPennsylvania,and the Appalachian regions of Kentucky, Tennessee, and all of West Virginia.[7][14]A decade later, Kurath split this into two discrete subdivisions: the "North Midland" beginning north of theOhio Rivervalley area and extending westward into central Indiana, central Illinois, central Ohio, Iowa, and northernMissouri,as well as parts ofNebraskaand northernKansas;and the "South Midland", which extends south of the Ohio River and expands westward to include Kentucky,southern Indiana,southern Illinois,southern Ohio,southern Missouri,Arkansas,southern Kansas, andOklahoma,west of theMississippi River.[15]Kurath and then later Craig Carver and the relatedDictionary of American Regional Englishbased their 1960s research only on lexical (vocabulary) characteristics, with Carver et al. determining the Midland non-existent according to their 1987 publication and preferring to identify Kurath's North Midland as merely an extension of the North and his South Midland as an extension of the South, based on some 800 lexical items.[16]

Conversely,William Labovand his team based their1990s researchlargely on phonological (sound) characteristics and re-identified the Midland area as a buffer zone between theInland SouthernandInland Northernaccent regions. In Labov et al.'s newer study, the "Midland" essentially coincides with Kurath's "North Midland", while the "South Midland" is now considered as largely a portion, or the northern fringe, of the larger 20th-century Southern accent region. Indeed, while the lexical and grammatical isoglosses encompass the Appalachian Mountains regardless of the Ohio River, the phonological boundary fairly closely follows along the Ohio River itself. More recent research has focused on grammatical characteristics and in particular a variable, possible combination of such characteristics.[17]

The original Midland dialect region, thus, has split off into having more of a Southern accent in southern Appalachia, while, the second half of the 20th century has seen the emergence of a uniqueWestern Pennsylvania accentin northern Appalachia (centered on Pittsburgh) as well as a uniquePhiladelphia accent.[12]

Mid-Atlantic region

[edit]The dialect region of theMid-Atlantic States—centered on Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Baltimore, Maryland; and Wilmington, Delaware—aligns to the Midland phonological definition except that it strongly resists thecot–caught mergerand traditionally has ashort-asplitthat is similar to New York City's, though still unique. Certain vocabulary is also specific to the Mid-Atlantic dialect, and particularly to itsPhiladelphia sub-dialect.

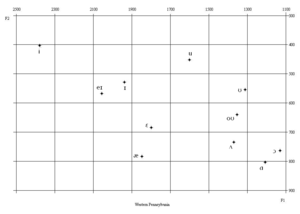

Western Pennsylvania

[edit]

The emerging and expanding dialect ofwesternand much of central Pennsylvania is, for many purposes, an extension of the South Midland;[18]it is spoken also inYoungstown, Ohio,10 miles west of the state line, as well asClarksburg, West Virginia.Like the Midland proper, the Western Pennsylvania accent features fronting of/oʊ/and/aʊ/,as well as positiveanymore.Its chief distinguishing features, however, also make it a separate dialect from the Midland one. These features include a completedLOT–THOUGHTmergerto a rounded vowel, which also causes a chain shift that drags theSTRUTvowel into the previous position ofLOT.The Western Pennsylvania accent, lightheartedly known as "Pittsburghese", is perhaps best known for the monophthongization ofMOUTH(/aʊ/to[aː]), such as the stereotypical Pittsburgh pronunciation ofdowntownasdahntahn.Despite having a Northern accent in the first half of the 20th century,Erie, Pennsylvania,is the only major Northern city to change its affiliation to Midland by now using the Western Pennsylvania accent.

Phonology and phonetics

[edit]

- Rhoticity: Midland speech is firmlyrhotic(or fullyr-pronouncing), like most North American English.

- Cot–caught mergerin transition: The merger of the vowel sounds inLOTandTHOUGHTis consistently in a transitional phase throughout most of the Midland region, showing neither a full presence nor absence of the merger. This involves a vowelmergerof the "short o"/ɑ/(as incotorstock) and "aw"/ɔ/(as incaughtorstalk) phonemes.

- Onboundary: A well-known phonological difference between Midland and Northern accents is that in the Midland, the single wordoncontains the phoneme/ɔ/(as incaught) rather than/ɑ/(as incot), as in the North. For this reason, one of the names for the boundary between the dialects of the Midland and the North is the "online ".

- EpentheticR:The phoneme sequence/wɑʃ/,as inwash,squash,andWashington,traditionally receives an additional/r/sound after the⟨a⟩,thus withWashingtonsounding like/ˈwɑrʃɪŋtən/or/ˈwɔrʃɪŋtən/.Likely inherited from Scots-Irish influence, this features ranges from D.C., Maryland, southern Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, Arkansas, West Texas, and the Midland dialect regions within Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Kansas.[19]Studied best of all in southern Pennsylvania, this feature may be declining.[20]

- The short-aphoneme,/æ/(TRAP),most commonly follows aGeneral American("continuous"and pre-nasal) distribution:/æ/is raised and tensed toward[eə]beforenasal consonants(such asfan) but remains low[æ]in other contexts (such asfact). An increasing number of speakers from central Ohio realize theTRAPvowel/æ/as open front[a].[21]

- Fronting of/oʊ/(GOAT):the phoneme/oʊ/(as ingoat) is fronter than in many other American accents, particularly those of the North; the phoneme is frequently realized as a diphthong with a central nucleus, approximating[əʊ~ɵʊ].[22]

- Fronting of/aʊ/(MOUTH):the diphthong/aʊ/(as inmouth) has a fronter nucleus than/aɪ/,approaching[æʊ~ɛɔ].[22]

- Fronting of/ʌ/(STRUT):among younger speakers,/ʌ/(as inbug,strut,what,etc.) is shifting strongly to the front:[ɜ].[23]

- Lowering of/eɪ/(FACE):the diphthong/eɪ/(as inface,reign,day,etc.) often has a lower nucleus than the Northern accents just above Midland region.[24]

- Phonologically, the South Midland remains slightly different from the North Midland (and more like the American South) in certain respects: its greater likelihood of a fronted/oʊ/,apin–pen merger,and a "glideless"/aɪ/vowel reminiscent of theSouthern U.S. accent,though/aɪ/monophthongization in the South Midland only tends to appear beforesonorant consonants:/m/,/n/,/l/,/r/.For example,firemay be pronounced something likefar.[18]Southern Indiana is the northernmost extent of this accent, forming what dialectologists refer to as the "HoosierApex "of the South Midland, with the accent locally known as the" Hoosier Twang ".

Grammar

[edit]- Positiveanymore:A common feature of the greater Midland area is so-called "positiveanymore":It is possible to use the adverbanymorewith the meaning "nowadays" in sentences withoutnegative polarity,such asAir travel is inconvenient anymore,[25]orThe streets of the city are very crowded anymore.[26]

- "Need+ participle ": Many speakers use the construction"need+ past participle ". Some examples include:

- The car needs washedto meanthe car needs to be washed

- They need repairedto meanthey need to be repaired

- So much still needs saidto meanso much still needs to be said

- To a lesser degree, a small number of other verbs have been reportedly used in this way too, such asThe baby likes cuddledorShe wants prepared.[17]As seen in these examples, it is also acceptable to use this construction with the wordswantandlike.[27]

- "All the+ comparative ": Speakers throughout the Midland (except central and southern Illinois and especially Iowa)[28]may use "all the[comparative form of an adjective]"to mean"as[adjective]as",when followed by a subject. Some examples include:[29]

- I held all the tighter I couldto meanI held as tight as I could

- That was all the higher she could jumpto meanThat was as high as she could jump

- This is all the more comfortable it getsto meanThis is as comfortable as it gets

- These same speakers may also alternatively use this form to mean "as much[comparative form of that adjective]as",when followed by such a subject. The corresponding examples would be:

- I held all the tighter I couldto meanI held as much tighter as I could

- That was all the higher she could jumpto meanThat was as much higher as she could jump

- This is all the more comfortable it getsto meanThis is as much more comfortable as it gets

- Alls:At the start of a sentence, "alls[subject] [verb] "can be used in place of"all that[subject] [verb] "to form anoun phrasefollowed byisorwas.For example (with the entire clause in italics): "Alls we broughtwas bread "or"Alls I want to dois sing a song ". This has been especially well-studied in southern Ohio, though it is widespread throughout the nation.[30]

- Many other grammatical constructions are also reported to varying degrees, predominantly of Scots-Irish origin, that could hypothetically define a Midland dialect, such as:what-all(an alternative towhat),wakened(an alternative towokeorwoke up),sick at the stomach,quarter till(as inquarter till twoto mean the time1:45), andwheneverto meanwhen(e.g.I cheered last Saturday whenever I won the award).[17]

Vocabulary

[edit]- bank(ed) barn,particularly in the East Midland (Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania), for a barn built into a hill with two-level access[31]

- berm,in the East Midland (Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania), andparking,in Illinois and Iowa, for aroad verge[25][32]

- blindsforwindow shutters

- carry-in,in the East Midland (Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio), forpotluck[33]

- carry-outfortake-out

- chuckhole,particularly in the East Midland (Indiana and Ohio),[34]andchughole,in the South Midland,[35]forpothole

- crawdadforcrayfish[25]

- dope,in Ohio, fordessert sauce[36]

- mango(ormango pepper) forgreenbell pepper,often whenpickledor stuffed[37]

- popin Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, western Missouri, northeastern Oklahoma, central Illinois, northern Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania;soda,in eastern Missouri and southern Illinois; andcokein theIndianapolis metropolitan area,southwestern Indiana,and theOklahoma City metropolitan area[25]

- sackfor anydisposable bag[25]

- tennis shoesfor any genericathletic shoes(gym shoesin Cincinnati and Chicago;[38]also, less often,running shoesin Cincinnati[25])

Today, the Midland is considered a transitional dialect region between the South and Inland North; however, the "South Midland" is a sub-region that phonologically speaking fits more with the South and even employs someSouthern vocabulary,for example, favoringy'allas the plural ofyou,whereas the rest of the (North) Midland favorsyou guys.Another possible Appalachian and South Midland variant isyou'uns(fromyou ones), though it remains most associated withWestern Pennsylvania English.[39]

Charleston

[edit]Today, the city ofCharleston, South Carolina,clearly has all the defining features of a mainstream Midland accent.[12]The vowels/oʊ/and/u/are extremely fronted, and yet not so not before/l/.[8]Also, the older, moretraditional Charleston accentwas extremely "non-Southern" in sound (as well as being highly unique), spoken throughout the South Carolina and GeorgiaLowcountry,but it mostly faded out of existence in the first half of the 20th century.[8]

Cincinnati

[edit]Older English speakers ofCincinnati, Ohio,have a phonological pattern quite distinct from the surrounding area (Boberg and Strassel 2000), while younger speakers now align to the general Midland accent. The older Cincinnati short-asystem is unique in the Midland. While there is no evidence for aphonemic split,the phonetic conditioning of short-ain conservative Cincinnati speech is similar to and originates from that ofNew York City,with the raising environments including nasals (m, n, ŋ), voiceless fricatives (f, unvoiced th, sh, s), and voiced stops (b, d, g). Weaker forms of this pattern are shown by speakers from nearbyDaytonandSpringfield.Boberg and Strassel (2000) reported that Cincinnati's traditional short-asystem was giving way among younger speakers to anasal systemsimilar to those found elsewhere in the Midland and the West.

St. Louis corridor

[edit]St. Louis,Missouri, is historically one among several (North) Midland cities, but it has developed some unique features of its own distinguishing it from the rest of the Midland. The area around St. Louis has been in dialectal transition throughout most of the 1900s until the present moment. The eldest generation of the area may exhibit a rapidly-declining merger of the phonemes/ɔr/(as infor) and/ɑr/(as infar) to the sound[ɒɹ],while leaving distinct/oʊr/(as infour), thus being one of the few American accents to still resist thehorse-hoarse merger(while also displaying thecard-cord merger). This merger has led to jokes referring to "I farty-far",[40]although a more accurateeye spellingwould be "I farty-four". Also, some St. Louis speakers, again usually the oldest ones, have/eɪ/instead of more typical/ɛ/before/ʒ/—thusmeasureis pronounced[ˈmeɪʒɚ]—andwash(as well asWashington) gains an/r/,becoming[wɒɹʃ]( "warsh" ).

Since the mid-1900s (namely, in speakers born from the 1920s to 1940s), however, a newer accent arose in a dialect "corridor" essentially following historicU.S. Route 66 in Illinois(nowInterstate 55 in Illinois) from Chicago southwest to St. Louis. Speakers of this modern "St. Louis Corridor" —including St. Louis, Fairbury, andSpringfield, Illinois—have gradually developed more features of theInland Northdialect, best recognized today as the Chicago accent. This 20th-century St. Louis accent's separating quality from the rest of the Midland is its strong resistance to thecot–caughtmerger and the most advanced development of theNorthern Cities Vowel Shift(NCS).[41]In the 20th century, Greater St. Louis therefore became a mix of Midland accents and Inland Northern (Chicago-like) accents.

Even more complicated, however, there is evidence that these Northern sound changes are reversing for the younger generations of speakers in the St. Louis area, who are re-embracing purely Midland-like accent features, though only at a regional level and therefore not including the aforementioned traditional features of the eldest generation. According to aUPennstudy, the St. Louis Corridor's one-generation period of embracing the NCS was followed by the next generation's "retreat of NCS features from Route 66 and a slight increase of NCS off of Route 66", in turn followed by the most recent generations' decreasing evidence of the NCS until it disappears altogether among the youngest speakers.[42]Thus, due to harboring two different dialects in the same geographic space, the "Corridor appears simultaneously as a single dialect area and two separate dialect areas".[43]

Texas

[edit]Rather than a proper Southern accent, several cities in Texas can be better described as having a Midland U.S. accent, as they lack the "true" Southern accent's full/aɪ/deletion and the oft-accompanying Southern Vowel Shift. Texan cities classifiable as such specifically include Abilene, Austin, San Antonio and Corpus Christi.Austin,in particular, has been reported in some speakers to show the South Midland (but not the Southern) variant of/aɪ/deletion mentioned above.[44]

References

[edit]- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:277)

- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:5, 263)

- ^Labov, William; Ash, Sharon; Boberg, Charles (1997). "Dialects of the United States."A National Map of The Regional Dialects of American English.University of Pennsylvania.

- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:263): "The Midland does not show the homogeneous character that marks the North in Chapter 14, or defines the South in Chapter 18. Many Midland cities have developed a distinct dialect character of their own[....] Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St Louis are quite distinct from the rest of the Midland[....]"

- ^Bierma, Nathan. "American 'Midland' has English dialect all its own."Chicago Tribune.

- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:137, 263, 266)

- ^abLabov, Ash & Boberg (2006:182)

- ^abcLabov, Ash & Boberg (2006:259)

- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:107, 139)

- ^abLabov, Ash & Boberg (2006:263, 303)

- ^Matthew J. Gordon, “The West and Midwest: Phonology,” in Edgar W. Schneider, ed.,Varieties of English: The Americas and the Caribbean(Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2008), 129–43, 129.

- ^abcLabov, Ash & Boberg (2006:135)

- ^Murray & Simon (2006:2)

- ^Kurath, Hans (1949).A Word Geography of the Eastern United States.University of Michigan.)

- ^Kurath, Hans; McDavid, Raven Ioor (1961).The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States.University of Michigan Press.

- ^Murray & Simon (2006:1)

- ^abcMurray & Simon (2006:15–16)

- ^abLabov, Ash & Boberg (2006:268)

- ^Kelly, John (2004). "Catching the Sound of the City".The Washington Post.The Washington Post Company.

- ^Barbara Johnstone, Barbara; et al. (2015).Pittsburgh Speech and Pittsburghese.Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KGp. p. 22.

- ^Thomas (2004:308)

- ^abLabov, Ash & Boberg (2006:255–258 and 262–265)

- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:266)

- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:94)

- ^abcdefVaux, Bert and Scott Golder. 2003.The Harvard Dialect SurveyArchived2016-04-30 at theWayback Machine.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Linguistics Department.

- ^Shields, Kenneth. 1997. Positive Anymore in Southeastern Pennsylvania.American Speech72(2). 217–220.https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/455794.pdf

- ^Maher, Zach and Jim Wood. 2011. Needs washed.Yale Grammatical Diversity Project: English in North America.(Available online athttp://ygdp.yale.edu/phenomena/needs-washed.Accessed on YYYY-MM-DD). Updated by Tom McCoy (2015) and Katie Martin (2018).

- ^Murray & Simon (2006:16)

- ^"All the Further".Yale Grammatical Diversity Project English in North America.Yale University. 2017.

- ^"Theallsconstruction".Yale Grammatical Diversity Project English in North America.Yale University. 2017.

- ^"Bank barn".Dictionary of American Regional English.Retrieved28 December2017.

- ^Metcalf, Allan A. (2000).How We Talk: American Regional English Today.Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 101.

- ^Metcalf, Allan A. (2000).How We Talk: American Regional English Today.Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 100.

- ^"Chuckhole".Word Reference.Word Reference. 2017.

- ^Dictionary.com.Dictionary.com Unabridged, based on theRandom House Dictionary.Random House, Inc. 2017.

- ^"Dope".The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language,Fifth Edition. 2017. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

- ^"Mango".Dictionary of American Regional English.Retrieved28 December2017.

- ^Sullivan, Mallorie (12 July 2017)."Gym shoes or tennis shoes? Twitter is running wild over the preferred term".Cincinnati Enquirer. Archived fromthe originalon 2023-08-31.Retrieved31 August2023.

- ^Murray & Simon (2006:28)

- ^Wolfram & Ward (2006:128)

- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:61)

- ^Friedman, Lauren (2015).A Convergence of Dialects in the St. Louis Corridor.Volume 21. Issue 2.Selected Papers from New Ways of Analyzing Variation(NWAV). 43. Article 8. University of Pennsylvania.

- ^"Northern Cities Panel".43rd NWAV. School of Literature's, Cultures, and Linguistics. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- ^Labov, Ash & Boberg (2006:126)

Bibliography

[edit]- Labov, William;Ash, Sharon;Boberg, Charles(2006).The Atlas of North American English.Berlin: Mouton-de Gruyter.ISBN3-11-016746-8.

- Murray, T. E.; Simon, B. L. (2006), "What is dialect? Revisiting the Midland",Language variation and change in the American Midland: A new look at 'Heartland' English,Amsterdam: John Benjamins,ISBN9027248966

- Thomas, Erik R. (2004), "Rural Southern White Accents", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.),A Handbook of Varieties of English,vol. 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 300–324,ISBN3-11-017532-0