Syllable

Asyllableis a unit of organization for a sequence ofspeech sounds,typically made up of a syllable nucleus (most often avowel) with optional initial and final margins (typically,consonants). Syllables are often considered thephonological"building blocks" ofwords.[1]They can influence therhythmof a language, itsprosody,itspoetic metreand itsstresspatterns. Speech can usually be divided up into a whole number of syllables: for example, the wordigniteis made of two syllables:igandnite.

Syllabic writingbegan several hundred years before thefirst letters.The earliest recorded syllables are on tablets written around 2800 BC in theSumeriancity ofUr.This shift frompictogramsto syllables has been called "the most important advance in thehistory of writing".[2]

A word that consists of a single syllable (likeEnglishdog) is called amonosyllable(and is said to bemonosyllabic). Similar terms includedisyllable(anddisyllabic;alsobisyllableandbisyllabic) for a word of two syllables;trisyllable(andtrisyllabic) for a word of three syllables; andpolysyllable(andpolysyllabic), which may refer either to a word of more than three syllables or to any word of more than one syllable.

Etymology

[edit]Syllableis anAnglo-Normanvariation ofOld Frenchsillabe,fromLatinsyllaba,fromKoine Greekσυλλαβήsyllabḗ(Greek pronunciation:[sylːabɛ̌ː]).συλλαβήmeans "the taken together", referring to letters that are taken together to make a single sound.[3]

συλλαβήis averbal nounfrom the verbσυλλαμβάνωsyllambánō,a compound of the prepositionσύνsýn"with" and the verbλαμβάνωlambánō"take".[4]The noun uses therootλαβ-,which appears in theaoristtense; thepresent tensestemλαμβάν-is formed by adding anasal infix⟨μ⟩⟨m⟩before theβband asuffix-αν-anat the end.[5]

Transcription

[edit]In theInternational Phonetic Alphabet(IPA), the fullstop ⟨.⟩ marks syllable breaks, as in the word "astronomical" ⟨/ˌæs.trə.ˈnɒm.ɪk.əl/⟩.

In practice, however, IPA transcription is typically divided into words by spaces, and often these spaces are also understood to be syllable breaks. In addition, the stress mark ⟨ˈ⟩ is placed immediately before a stressed syllable, and when the stressed syllable is in the middle of a word, in practice, the stress mark also marks a syllable break, for example in the word "understood" ⟨/ʌndərˈstʊd/⟩ (though the syllable boundary may still be explicitly marked with a full stop,[6]e.g. ⟨/ʌn.dər.ˈstʊd/⟩).

When a word space comes in the middle of a syllable (that is, when a syllable spans words), a tie bar ⟨‿⟩ can be used forliaison,as in the French combinationles amis⟨/lɛ.z‿a.mi/⟩. The liaison tie is also used to join lexical words intophonological words,for examplehot dog⟨/ˈhɒt‿dɒɡ/⟩.

A Greek sigma,⟨σ⟩,is used as awild cardfor 'syllable', and a dollar/peso sign,⟨$⟩,marks a syllable boundary where the usual fullstop might be misunderstood. For example,⟨σσ⟩is a pair of syllables, and⟨V$⟩is a syllable-final vowel.

Components

[edit]

Typical model

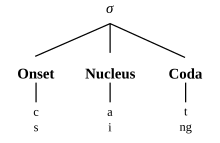

[edit]In the typical theory[citation needed]of syllable structure, the general structure of a syllable (σ) consists of three segments. These segments are grouped into two components:

- Onset(ω): Aconsonantorconsonant cluster,obligatory in some languages, optional or even restricted in others

- Rime(ρ): Right branch, contrasts with onset, splits into nucleus and coda

- Nucleus(ν): Avowelorsyllabic consonant,obligatory in most languages

- Coda(κ): A consonant or consonant cluster, optional in some languages, highly restricted or prohibited in others

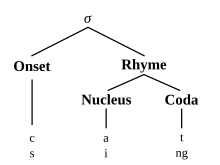

The syllable is usually considered right-branching, i.e. nucleus and coda are grouped together as a "rime" and are only distinguished at the second level.

Thenucleusis usually the vowel in the middle of a syllable. Theonsetis the sound or sounds occurring before the nucleus, and thecoda(literally 'tail') is the sound or sounds that follow the nucleus. They are sometimes collectively known as theshell.The termrimecovers the nucleus plus coda. In the one-syllable English wordcat,the nucleus isa(the sound that can be shouted or sung on its own), the onsetc,the codat,and the rimeat.This syllable can be abstracted as aconsonant-vowel-consonantsyllable, abbreviatedCVC.Languages vary greatly in the restrictions on the sounds making up the onset, nucleus and coda of a syllable, according to what is termed a language'sphonotactics.

Although every syllable has supra-segmental features, these are usually ignored if not semantically relevant, e.g. intonal languages.

Chinese model

[edit]

In the syllable structure ofSinitic languages,the onset is replaced with an initial, and a semivowel or liquid forms another segment, called the medial. These four segments are grouped into two slightly different components:[example needed]

- Initial⟨ι⟩:Optional onset, excluding semivowels

- Final⟨φ⟩:Medial, nucleus, and final consonant[7]

- Tone⟨τ⟩:May be carried by the syllable as a whole or by the rime

In many languages of theMainland Southeast Asia linguistic area,such asChinese,the syllable structure is expanded to include an additional, optionalmedialsegment located between the onset (often termed theinitialin this context) and the rime. The medial is normally asemivowel,butreconstructions of Old Chinesegenerally includeliquidmedials (/r/in modern reconstructions,/l/in older versions), and many reconstructions ofMiddle Chineseinclude a medial contrast between/i/and/j/,where the/i/functions phonologically as a glide rather than as part of the nucleus. In addition, many reconstructions of both Old and Middle Chinese include complex medials such as/rj/,/ji/,/jw/and/jwi/.The medial groups phonologically with the rime rather than the onset, and the combination of medial and rime is collectively known as thefinal.

Some linguists, especially when discussing the modern Chinese varieties, use the terms "final" and "rime" interchangeably. Inhistorical Chinese phonology,however, the distinction between "final" (including the medial) and "rime" (not including the medial) is important in understanding therime dictionariesandrime tablesthat form the primary sources forMiddle Chinese,and as a result most authors distinguish the two according to the above definition.

Grouping of components

[edit]

In some theories of phonology, syllable structures are displayed astree diagrams(similar to the trees found in some types of syntax). Not all phonologists agree that syllables have internal structure; in fact, some phonologists doubt the existence of the syllable as a theoretical entity.[9]

There are many arguments for a hierarchical relationship, rather than a linear one, between the syllable constituents. One hierarchical model groups the syllable nucleus and coda into an intermediate level, therime.The hierarchical model accounts for the role that thenucleus+codaconstituent plays inverse(i.e.,rhymingwords such ascatandbatare formed by matching both the nucleus and coda, or the entire rime), and for thedistinction between heavy and light syllables,which plays a role in phonological processes such as, for example,sound changeinOld Englishscipuandwordu,where in a process called high vowel deletion (HVD), the nominative/accusative plural of single light-syllable roots (like "*scip-" ) got a "u" ending in OE, whereas heavy syllable roots (like "*word-" ) would not, giving "scip-u" but "word-∅".[10][11][12]

Body

[edit]

In some traditional descriptions of certain languages such asCreeandOjibwe,the syllable is considered left-branching, i.e. onset and nucleus group below a higher-level unit, called a "body" or "core". This contrasts with the coda.

Rime

[edit]Therimeorrhymeof a syllable consists of anucleusand an optionalcoda.It is the part of the syllable used in mostpoetic rhymes,and the part that is lengthened or stressed when a person elongates or stresses a word in speech.

The rime is usually the portion of a syllable from the firstvowelto the end. For example,/æt/is the rime of all of the wordsat,sat,andflat.However, the nucleus does not necessarily need to be a vowel in some languages, such as English. For instance, the rime of the second syllables of the wordsbottleandfiddleis just/l/,aliquid consonant.

Just as the rime branches into the nucleus and coda, the nucleus and coda may each branch into multiplephonemes.The limit for the number of phonemes which may be contained in each varies by language. For example,Japaneseand mostSino-Tibetan languagesdo not have consonant clusters at the beginning or end of syllables, whereas many Eastern European languages can have more than two consonants at the beginning or end of the syllable. In English, the onset may have up to three consonants, and the coda four.[13]

Rimeandrhymeare variants of the same word, but the rarer formrimeis sometimes used to mean specificallysyllable rimeto differentiate it from the concept of poeticrhyme.This distinction is not made by some linguists and does not appear in most dictionaries.

| structure: | syllable = | onset | + rhyme |

|---|---|---|---|

| C+V+C*: | C1(C2)V1(V2)(C3)(C4) = | C1(C2) | + V1(V2)(C3)(C4) |

| V+C*: | V1(V2)(C3)(C4) = | ∅ | + V1(V2)(C3)(C4) |

Weight

[edit]

Aheavy syllableis generally one with abranching rime,i.e. it is either aclosed syllablethat ends in a consonant, or a syllable with abranching nucleus,i.e. a long vowel ordiphthong.The name is a metaphor, based on the nucleus or coda having lines that branch in a tree diagram.

In some languages, heavy syllables include both VV (branching nucleus) and VC (branching rime) syllables, contrasted with V, which is alight syllable. In other languages, only VV syllables are considered heavy, while both VC and V syllables are light. Some languages distinguish a third type ofsuperheavy syllable,which consists of VVC syllables (with both a branching nucleus and rime) or VCC syllables (with a coda consisting of two or more consonants) or both.

Inmoraic theory,heavy syllables are said to have two moras, while light syllables are said to have one and superheavy syllables are said to have three.Japanese phonologyis generally described this way.

Many languages forbid superheavy syllables, while a significant number forbid any heavy syllable. Some languages strive for constant syllable weight; for example, in stressed, non-final syllables inItalian,short vowels co-occur with closed syllables while long vowels co-occur with open syllables, so that all such syllables are heavy (not light or superheavy).

The difference between heavy and light frequently determines which syllables receivestress– this is the case inLatinandArabic,for example. The system ofpoetic meterin many classical languages, such asClassical Greek,Classical Latin,Old TamilandSanskrit,is based on syllable weight rather than stress (so-calledquantitative rhythmorquantitative meter).

Syllabification

[edit]Syllabificationis the separation of a word into syllables, whether spoken or written. In most languages, the actually spoken syllables are the basis of syllabification in writing too. Due to the very weak correspondence between sounds and letters in the spelling of modern English, for example, written syllabification in English has to be based mostly on etymological i.e. morphological instead of phonetic principles. English written syllables therefore do not correspond to the actually spoken syllables of the living language.

Phonotactic rules determine which sounds are allowed or disallowed in each part of the syllable.Englishallows very complicated syllables; syllables may begin with up to three consonants (as instrength), and occasionally end with as many as four[14](as inangsts,pronounced [æŋsts]). Many other languages are much more restricted;Japanese,for example, only allows/ɴ/and achronemein a coda, and theoretically has no consonant clusters at all, as the onset is composed of at most one consonant.[15]

The linking of a word-final consonant to a vowel beginning the word immediately following it forms a regular part of the phonetics of some languages, including Spanish, Hungarian, and Turkish. Thus, in Spanish, the phraselos hombres('the men') is pronounced[loˈsom.bɾes],Hungarianaz ember('the human') as[ɒˈzɛm.bɛr],and Turkishnefret ettim('I hated it') as[nefˈɾe.tet.tim].In Italian, a final[j]sound can be moved to the next syllable in enchainement, sometimes with a gemination: e.g.,non ne ho mai avuti('I've never had any of them') is broken into syllables as[non.neˈɔ.ma.jaˈvuːti]andio ci vado e lei anche('I go there and she does as well') is realized as[jo.tʃiˈvaːdo.e.lɛjˈjaŋ.ke].A related phenomenon, called consonant mutation, is found in the Celtic languages like Irish and Welsh, whereby unwritten (but historical) final consonants affect the initial consonant of the following word.

Ambisyllabicity

[edit]There can be disagreement about the location of some divisions between syllables in spoken language. The problems of dealing with such cases have been most commonly discussed with relation to English. In the case of a word such ashurry,the division may be/hʌr.i/or/hʌ.ri/,neither of which seems a satisfactory analysis for anon-rhotic accentsuch as RP (British English):/hʌr.i/results in a syllable-final/r/,which is not normally found, while/hʌ.ri/gives a syllable-final short stressed vowel, which is also non-occurring. Arguments can be made in favour of one solution or the other: A general rule has been proposed that states that "Subject to certain conditions..., consonants are syllabified with the more strongly stressed of two flanking syllables",[16]while many other phonologists prefer to divide syllables with the consonant or consonants attached to the following syllable wherever possible. However, an alternative that has received some support is to treat an intervocalic consonant asambisyllabic,i.e. belonging both to the preceding and to the following syllable:/hʌṛi/.This is discussed in more detail inEnglish phonology § Phonotactics.

Onset

[edit]Theonset(also known asanlaut) is the consonant sound or sounds at the beginning of a syllable, occurring before thenucleus.Most syllables have an onset. Syllables without an onset may be said to have anemptyorzeroonset– that is, nothing where the onset would be.

Onset cluster

[edit]Some languages restrict onsets to be only a single consonant, while others allow multiconsonant onsets according to various rules. For example, in English, onsets such aspr-,pl-andtr-are possible buttl-is not, andsk-is possible butks-is not. InGreek,however, bothks-andtl-are possible onsets, while contrarily inClassical Arabicno multiconsonant onsets are allowed at all.

Null onset

[edit]Some languages forbidnull onsets.In these languages, words beginning in a vowel, like the English wordat,are impossible.

This is less strange than it may appear at first, as most such languages allow syllables to begin with a phonemicglottal stop(the sound in the middle of Englishuh-ohor, in some dialects, the double T inbutton,represented in theIPAas/ʔ/). In English, a word that begins with a vowel may be pronounced with anepentheticglottal stop when following a pause, though the glottal stop may not be aphonemein the language.

Few languages make a phonemic distinction between a word beginning with a vowel and a word beginning with a glottal stop followed by a vowel, since the distinction will generally only be audible following another word. However,Malteseand somePolynesian languagesdo make such a distinction, as inHawaiian/ahi/('fire') and/ʔahi/ ←/kahi/('tuna') and Maltese/∅/←Arabic/h/and Maltese/k~ʔ/← Arabic/q/.

AshkenaziandSephardi Hebrewmay commonly ignoreא,הandע,and Arabic forbid empty onsets. The namesIsrael,Abel,Abraham,Omar,Abdullah,andIraqappear not to have onsets in the first syllable, but in the original Hebrew and Arabic forms they actually begin with various consonants: the semivowel/j/inיִשְׂרָאֵלyisra'él,the glottal fricative in/h/הֶבֶלheḇel,the glottal stop/ʔ/inאַבְרָהָם'aḇrāhām,or the pharyngeal fricative/ʕ/inعُمَرʿumar,عَبْدُ ٱللّٰʿabdu llāh,andعِرَاقʿirāq.Conversely, theArrernte languageof central Australia may prohibit onsets altogether; if so, all syllables have theunderlying shapeVC(C).[17]

The difference between a syllable with a null onset and one beginning with a glottal stop is often purely a difference ofphonologicalanalysis, rather than the actual pronunciation of the syllable. In some cases, the pronunciation of a (putatively) vowel-initial word when following another word – particularly, whether or not a glottal stop is inserted – indicates whether the word should be considered to have a null onset. For example, manyRomance languagessuch asSpanishnever insert such a glottal stop, whileEnglishdoes so only some of the time, depending on factors such as conversation speed; in both cases, this suggests that the words in question are truly vowel-initial.

But there are exceptions here, too. For example, standardGerman(excluding many southern accents) andArabicboth require that a glottal stop be inserted between a word and a following, putatively vowel-initial word. Yet such words are perceived to begin with a vowel in German but a glottal stop in Arabic. The reason for this has to do with other properties of the two languages. For example, a glottal stop does not occur in other situations in German, e.g. before a consonant or at the end of word. On the other hand, in Arabic, not only does a glottal stop occur in such situations (e.g. Classical/saʔala/"he asked",/raʔj/"opinion",/dˤawʔ/"light" ), but it occurs in alternations that are clearly indicative of its phonemic status (cf. Classical/kaːtib/"writer" vs. /maktuːb/"written",/ʔaːkil/"eater" vs./maʔkuːl/"eaten" ). In other words, while the glottal stop is predictable in German (inserted only if a stressed syllable would otherwise begin with a vowel),[18]the same sound is a regular consonantal phoneme in Arabic. The status of this consonant in the respective writing systems corresponds to this difference: there is no reflex of the glottal stop inGerman orthography,but there is a letter in the Arabic alphabet (Hamza(ء)).

The writing system of a language may not correspond with the phonological analysis of the language in terms of its handling of (potentially) null onsets. For example, in some languages written in theLatin alphabet,an initial glottal stop is left unwritten (see the German example); on the other hand, some languages written using non-Latin alphabets such asabjadsandabugidashave a specialzero consonantto represent a null onset. As an example, inHangul,the alphabet of theKorean language,a null onset is represented with ㅇ at the left or top section of agrapheme,as in역"station", pronouncedyeok,where thediphthongyeois the nucleus andkis the coda.

Nucleus

[edit]| Word | Nucleus |

|---|---|

| cat[kæt] | [æ] |

| bed[bɛd] | [ɛ] |

| ode[oʊd] | [oʊ] |

| beet[bit] | [i] |

| bite[baɪt] | [aɪ] |

| rain[ɻeɪn] | [eɪ] |

| bitten [ˈbɪt.ən]or[ˈbɪt.n̩] |

[ɪ] [ə]or[n̩] |

Thenucleusis usually the vowel in the middle of a syllable. Generally, every syllable requires a nucleus (sometimes called thepeak), and the minimal syllable consists only of a nucleus, as in the English words "eye" or "owe". The syllable nucleus is usually a vowel, in the form of amonophthong,diphthong,ortriphthong,but sometimes is asyllabic consonant.

In mostGermanic languages,lax vowelscan occur only in closed syllables. Therefore, these vowels are also calledchecked vowels,as opposed to the tense vowels that are calledfree vowelsbecause they can occur even in open syllables.

Consonant nucleus

[edit]The notion of syllable is challenged by languages that allow long strings ofobstruentswithout any intervening vowel orsonorant.By far the most common syllabic consonants are sonorants like[l],[r],[m],[n]or[ŋ],as in Englishbottle,church(in rhotic accents),rhythm,buttonandlock'nkey.However, English allows syllabic obstruents in a few para-verbalonomatopoeicutterances such asshh(used to command silence) andpsst(used to attract attention). All of these have been analyzed as phonemically syllabic. Obstruent-only syllables also occur phonetically in some prosodic situations when unstressed vowels elide between obstruents, as inpotato[pʰˈteɪɾəʊ]andtoday[tʰˈdeɪ],which do not change in their number of syllables despite losing a syllabic nucleus.

A few languages have so-calledsyllabic fricatives,also known asfricative vowels,at the phonemic level. (In the context ofChinese phonology,the related but non-synonymous termapical vowelis commonly used.)Mandarin Chineseis famous for having such sounds in at least some of its dialects, for example thepinyinsyllablessī shī rī,usually pronounced[sź̩ʂʐ̩́ʐʐ̩́],respectively. Though, like the nucleus of rhotic Englishchurch,there is debate over whether these nuclei are consonants or vowels.

Languages of the northwest coast of North America, includingSalishan,WakashanandChinookanlanguages, allowstop consonantsandvoiceless fricativesas syllables at the phonemic level, in even the most careful enunciation. An example is Chinook[ɬtʰpʰt͡ʃʰkʰtʰ]'those two women are coming this way out of the water'. Linguists have analyzed this situation in various ways, some arguing that such syllables have no nucleus at all and some arguing that the concept of "syllable" cannot clearly be applied at all to these languages.

Other examples:

- Nuxálk(Bella Coola)

- [ɬχʷtʰɬt͡sʰxʷ]'you spat on me'

- [t͡sʼkʰtʰskʷʰt͡sʼ]'he arrived'

- [xɬpʼχʷɬtʰɬpʰɬɬs]'he had in his possession a bunchberry plant'[19]

- [sxs]'seal blubber'

In Bagemihl's survey of previous analyses, he finds that the Bella Coola word/t͡sʼktskʷt͡sʼ/'he arrived' would have been parsed into 0, 2, 3, 5, or 6 syllables depending on which analysis is used. One analysis would consider all vowel and consonant segments as syllable nuclei, another would consider only a small subset (fricativesorsibilants) as nuclei candidates, and another would simply deny the existence of syllables completely. However, when working with recordings rather than transcriptions, the syllables can be obvious in such languages, and native speakers have strong intuitions as to what the syllables are.

This type of phenomenon has also been reported inBerber languages(such as IndlawnTashlhiyt Berber),Mon–Khmer languages(such asSemai,Temiar,Khmu) and the Ōgami dialect ofMiyako,aRyukyuan language.[20]

- Indlawn Tashlhiyt Berber

- [tftktsttfktstt]'you sprained it and then gave it'

- [rkkm]'rot' (imperf.)[21][22]

- Semai

- [kckmrʔɛːc]'short, fat arms'[23]

Coda

[edit]Thecoda(also known asauslaut) comprises theconsonantsounds of a syllable that follow thenucleus.The sequence of nucleus and coda is called arime.Some syllables consist of only a nucleus, only an onset and a nucleus with no coda, or only a nucleus and coda with no onset.

Thephonotacticsof many languages forbid syllable codas. Examples areSwahiliandHawaiian.In others, codas are restricted to a small subset of the consonants that appear in onset position. At a phonemic level inJapanese,for example, a coda may only be a nasal (homorganic with any following consonant) or, in the middle of a word,geminationof the following consonant. (On a phonetic level, other codas occur due to elision of /i/ and /u/.) In other languages, nearly any consonant allowed as an onset is also allowed in the coda, evenclusters of consonants.In English, for example, all onset consonants except/h/are allowed as syllable codas.

If the coda consists of a consonant cluster, the sonority typically decreases from first to last, as in the English wordhelp.This is called thesonority hierarchy(or sonority scale).[24]English onset and coda clusters are therefore different. The onset/str/instrengthsdoes not appear as a coda in any English word. However, some clusters do occur as both onsets and codas, such as/st/instardust.The sonority hierarchy is more strict in some languages and less strict in others.

Open and closed

[edit]A coda-less syllable of the form V, CV, CCV, etc. (V = vowel, C = consonant) is called anopen syllableorfree syllable,while a syllable that has a coda (VC, CVC, CVCC, etc.) is called aclosed syllableorchecked syllable.They have nothing to do withopenandclose vowels,but are defined according to the phoneme that ends the syllable: a vowel (open syllable) or a consonant (closed syllable). Almost all languages allow open syllables, but some, such asHawaiian,do not have closed syllables.

When a syllable is not the last syllable in a word, the nucleus normally must be followed by two consonants in order for the syllable to be closed. This is because a single following consonant is typically considered the onset of the following syllable. For example, Spanishcasar( "to marry" ) is composed of an open syllable followed by a closed syllable (ca-sar), whereascansar"to get tired" is composed of two closed syllables (can-sar). When ageminate(double) consonant occurs, the syllable boundary occurs in the middle, e.g. Italianpanna"cream" (pan-na); cf. Italianpane"bread" (pa-ne).

English words may consist of a single closed syllable, with nucleus denoted by ν, and coda denoted by κ:

- in:ν =/ɪ/,κ =/n/

- cup:ν =/ʌ/,κ =/p/

- tall:ν =/ɔː/,κ =/l/

- milk:ν =/ɪ/,κ =/lk/

- tints:ν =/ɪ/,κ =/nts/

- fifths:ν =/ɪ/,κ =/fθs/

- sixths:ν =/ɪ/,κ =/ksθs/

- twelfths:ν =/ɛ/,κ =/lfθs/

- strengths:ν =/ɛ/,κ =/ŋθs/

English words may also consist of a single open syllable, ending in a nucleus, without a coda:

- glue,ν =/uː/

- pie,ν =/aɪ/

- though,ν =/oʊ/

- boy,ν =/ɔɪ/

A list of examples of syllable codas in English is found atEnglish phonology#Coda.

Null coda

[edit]Some languages, such asHawaiian,forbid codas, so that all syllables are open.

Suprasegmental features

[edit]The domain ofsuprasegmental featuresis a syllable (or some larger unit), but not a specific sound. That is to say, these features may effect more than a single segment, and possibly all segments of a syllable:

Sometimessyllable lengthis also counted as a suprasegmental feature; for example, in some Germanic languages, long vowels may only exist with short consonants and vice versa. However, syllables can be analyzed as compositions of long and short phonemes, as in Finnish and Japanese, where consonant gemination and vowel length are independent.

Tone

[edit]In most languages, thepitchorpitch contourin which a syllable is pronounced conveys shades of meaning such as emphasis or surprise, or distinguishes a statement from a question. In tonal languages, however, the pitch affects the basic lexical meaning (e.g. "cat" vs. "dog" ) or grammatical meaning (e.g. past vs. present). In some languages, only the pitch itself (e.g. high vs. low) has this effect, while in others, especially East Asian languages such asChinese,ThaiorVietnamese,the shape or contour (e.g. level vs. rising vs. falling) also needs to be distinguished.

Accent

[edit]Syllable structure often interacts with stress or pitch accent. InLatin,for example, stress is regularly determined bysyllable weight,a syllable counting as heavy if it has at least one of the following:

In each case, the syllable is considered to have twomorae.

The first syllable of a word is theinitial syllableand the last syllable is thefinal syllable.

In languages accented on one of the last three syllables, the last syllable is called theultima,the next-to-last is called thepenult,and the third syllable from the end is called the antepenult. These terms come from Latinultima"last",paenultima"almost last", andantepaenultima"before almost last".

InAncient Greek,there are threeaccent marks(acute, circumflex, and grave), and terms were used to describe words based on the position and type of accent. Some of these terms are used in the description of other languages.

| Placement of accent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antepenult | Penult | Ultima | ||

| Type of accent |

Circumflex | — | properispomenon | perispomenon |

| Acute | proparoxytone | paroxytone | oxytone | |

| Any | barytone | — | ||

History

[edit]Guilhem Molinier,a member of theConsistori del Gay Saber,which was the first literary academy in the world and held theFloral Gamesto award the besttroubadourwith thevioleta d'aurtop prize, gave a definition of the syllable in hisLeys d'amor(1328–1337), a book aimed at regulating then-flourishingOccitanpoetry:

Sillaba votz es literals. |

A syllable is the sound of several letters, |

See also

[edit]- English phonology#Phonotactics.Covers syllable structure in English.

- Entering tone

- IPA symbols for syllables

- Line (poetry)

- List of the longest English words with one syllable

- Minor syllable

- Mora (linguistics)

- Phonology

- Pitch accent

- Stress (linguistics)

- Syllabarywriting system

- Syllabic consonant

- Syllabification

- Syllable (computing)

- Timing (linguistics)

- Vocalese

References

[edit]- ^de Jong, Kenneth (2003). "Temporal constraints and characterising syllable structuring". InLocal, John;Ogden, Richard; Temple, Rosalind (eds.).Phonetic Interpretation: Papers in Laboratory Phonology VI.Cambridge University Press. pp. 253–268.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511486425.015.ISBN978-0-521-82402-6.Page 254.

- ^Hooker, J. T. (1990). "Introduction".Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet.University of California Press; British Museum. p. 8.ISBN0-520-07431-9.

- ^Harper, Douglas."syllable".Online Etymology Dictionary.Retrieved2015-01-05.

- ^λαμβάνω.Liddell, Henry George;Scott, Robert;A Greek–English Lexiconat thePerseus Project

- ^Smyth 1920,§523: present stems formed by suffixes containingν

- ^International Phonetic Association(December 1989). "Report on the 1989 Kiel Convention: International Phonetic Association".Journal of the International Phonetic Association.19(2). Cambridge University Press: 75–76.doi:10.1017/S0025100300003868.S2CID249412330.

- ^More generally, the letter φ indicates a prosodicfootof two syllables

- ^More generally, the letter μ indicates amora

- ^For discussion of the theoretical existence of the syllable see"CUNY Conference on the Syllable".CUNY Phonology Forum.CUNY Graduate Center. Archived fromthe originalon 23 September 2015.Retrieved21 June2022.

- ^Bermúdez-Otero, Ricardo (2015)."The life cycle of High Vowel Deletion in Old English: from prosody to stratification and loss"(PDF).p. 2.

- ^Fikkert, Paula; Dresher, Elan; Lahiri, Aditi (2006). "Chapter 6, Prosodic Preferences: From Old English to Early Modern English".The Handbook of the History of English(PDF).pp. 134–135.ISBN9780470757048.

- ^Feng, Shengli (2003).A Prosodic Grammar of Chinese.University of Kansas. p. 3.

- ^Hultzén, Lee S. (1965)."Consonant Clusters in English".American Speech.40(1): 5–19.doi:10.2307/454173.ISSN0003-1283.

- ^Hultzén, Lee S. (1965)."Consonant Clusters in English".American Speech.40(1): 5–19.doi:10.2307/454173.ISSN0003-1283.

- ^Shibatani, Masayoshi (1987). "Japanese". In Bernard Comrie (ed.).The World's Major Languages.Oxford University Press. pp. 855–80.ISBN0-19-520521-9.

- ^Wells, John C.(1990). "Syllabification and allophony". In Ramsaran, Susan (ed.).Studies in the pronunciation of English: a commemorative volume in honour of A.C. Gimson.Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 76–86.ISBN9781138918658.

- ^Breen, Gavan; Pensalfini, Rob (1999)."Arrernte: A Language with No Syllable Onsets"(PDF).Linguistic Inquiry.30(1): 1–25.doi:10.1162/002438999553940.JSTOR4179048.S2CID57564955.

- ^Wiese, Richard (2000).Phonology of German.Oxford University Press. pp. 58–61.ISBN9780198299509.

- ^Bagemihl 1991,pp. 589, 593, 627

- ^Pellard, Thomas (2010). "Ōgami (Miyako Ryukyuan)". In Shimoji, Michinori (ed.).An introduction to Ryukyuan languages(PDF).Fuchū, Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. pp. 113–166.ISBN978-4-86337-072-2.Retrieved21 June2022.HALhal-00529598

- ^Dell & Elmedlaoui 1985

- ^Dell & Elmedlaoui 1988

- ^Sloan 1988

- ^Harrington, Jonathan; Cox, Felicity (August 2014)."Syllable and foot: The syllable and phonotactic constraints".Department of Linguistics.Macquarie University.Retrieved21 June2022.

Sources and recommended reading

[edit]- Bagemihl, Bruce(1991). "Syllable structure in Bella Coola".Linguistic Inquiry.22(4): 589–646.JSTOR4178744.

- Clements, George N.;Keyser, Samuel J.(1983).CV phonology: a generative theory of the syllable.Linguistic Inquiry Monographs. Vol. 9. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.ISBN9780262030984.

- Dell, François; Elmedlaoui, Mohamed (1985). "Syllabic consonants and syllabification in Imdlawn Tashlhiyt Berber".Journal of African Languages and Linguistics.7(2): 105–130.doi:10.1515/jall.1985.7.2.105.S2CID29304770.

- Dell, François; Elmedlaoui, Mohamed (1988). "Syllabic consonants in Berber: Some new evidence".Journal of African Languages and Linguistics.10:1–17.doi:10.1515/jall.1988.10.1.1.S2CID144470527.

- Ladefoged, Peter(2001).A course in phonetics(4th ed.).Fort Worth, TX:Harcourt College Publishers.ISBN0-15-507319-2.

- Sloan, Kerry (1988). "Bare-Consonant Reduplication: Implications for a Prosodic Theory of Reduplication". In Borer, Hagit (ed.).The Proceedings of the Seventh West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics.WCCFL 7. Irvine, CA: University of Chicago Press. pp. 319–330.ISBN9780937073407.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920).A Greek Grammar for Colleges.American Book Company.Retrieved1 January2014– viaCCEL.