Okra

| Okra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mature and developing fruits (pods) (Hong Kong) | |

| |

| Longitudinal section of fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Genus: | Abelmoschus |

| Species: | A. esculentus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Abelmoschus esculentus | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Okra(US:/ˈoʊkrə/,UK:/ˈɒkrə/),Abelmoschus esculentus,known in some English-speaking countries aslady's fingers,[2][3]is aflowering plantin themallow familynative toEast Africa.[4]Cultivated in tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate regions around the world for its ediblegreen seed pods,okra is featured in thecuisinesof many countries.[5]

Description

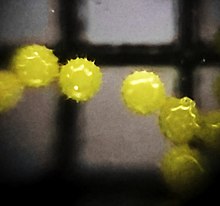

[edit]The species is aperennial,often cultivated as anannualin temperate climates, often growing to around 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) tall. As a member of the Malvaceae, it is related to such species ascotton,cocoa,andhibiscus.Theleavesare 10–20 centimetres (4–8 in) long and broad, palmately lobed with 5–7 lobes. Theflowersare4–8 cm (1+5⁄8–3+1⁄8in) in diameter, with five white to yellow petals, often with a red or purple spot at the base of each petal. The pollens are spherical and approximately 188micronsindiameter.Thefruitis acapsuleup to 18 cm (7 in) long withpentagonalcross-section, containing numerousseeds.

Etymology

[edit]AbelmoschusisNeo-LatinfromArabic:أَبُو المِسْك,romanized:ʾabū l-misk,lit. 'father ofmusk',[6]whileesculentusisLatinfor being fit for human consumption.[7]

The first use of the wordokra(alternatively;okroorochro) appeared in 1679 in theColony of Virginia,deriving fromIgbo:ọ́kwụ̀rụ̀.[8]The wordgumbowas first used inAmerican Englisharound 1805, derived fromLouisiana Creole,[9]but originates from eitherUmbundu:ochinggõmbo[10]orKimbundu:kingombo.[11]Even though the wordgumbooften refers to the dishgumboin most of the United States, many places in theDeep Southmay have used it to refer to the pods and plant as well as many other variants of the word found across theAfrican diaspora in the Americas.[12]

Origin and distribution

[edit]

Okra is anallopolyploidof uncertain parentage. However, proposed parents includeAbelmoschus ficulneus,A. tuberculatusand a reported "diploid" form of okra.[13]Truly wild (as opposed tonaturalised) populations are not known with certainty, and the West African variety has been described as acultigen.[14]

Okra originated in East Africa inEthiopia,Eritrea,and easternSudan.[4][15]Okra was introduced to Europe by theUmayyad conquest of Hispania.One of the earliest accounts is byAbu al-Abbas al-Nabati,who visitedAyyubid Egyptin 1216 and described the plant under cultivation by the locals who ate the tender, young pods withmeal.[16]From Arabia, the plant spread around the shores of theMediterranean Seaand eastward.[17]

The plant was introduced to theAmericasby ships plying theAtlantic slave trade[18]by 1658, when its presence was recorded inBrazil.It was further documented inSurinamein 1686. Okra may have been introduced to southeasternNorth Americafrom Africa in the early 18th century. By 1748, it was being grown as far north asPhiladelphia.[19]Thomas Jeffersonnoted it was well established inVirginiaby 1781. It was commonplace throughout theSouthern United Statesby 1800, and the first mention of differentcultivarswas in 1806.[4]

Cultivation

[edit]

Abelmoschus esculentusis cultivated throughout the tropical and warm temperate regions of the world for its fibrous fruits or pods containing round, white seeds. It is among the most heat- anddrought-tolerantvegetable species in the world and will toleratesoilswith heavyclayand intermittent moisture, but frost can damage the pods. In cultivation, the seeds are soaked overnight prior to planting to a depth of1–2 cm (3⁄8–13⁄16in). It prefers a soil temperature of at least 20 °C (68 °F) forgermination,which occurs between six days (soaked seeds) and three weeks. As a tropical plant, it also requires a lot of sunlight, and it should also be cultivated in soil that has a pH between 5.8 and 7, ideally on the acidic side.[20]Seedlings require ample water. The seed pods rapidly become fibrous and woody and, to be edible as avegetable,must be harvested when immature, usually within a week afterpollination.[21]The first harvest will typically be ready about 2 months after planting, and it will be approximately 2–3 inches (51–76 mm) long.[20]

The most common disease afflicting the okra plant isverticillium wilt,often causing a yellowing and wilting of the leaves. Other diseases includepowdery mildewin dry tropical regions,leaf spots,yellow mosaicandroot-knot nematodes.Resistance to yellow mosaic virus inA. esculentuswas transferred through a cross withAbelmoschus manihotand resulted in a new variety calledParbhani kranti.[22]

In the U.S. much of the supply is grown in Florida, especially aroundDadein southern Florida.[23][24]Okra is grown throughout the state to some degree, so okra is available ten months of the year.[23]Yields range from less than 18,000 pounds per acre (20,000 kg/ha) to over 30,000 pounds per acre (34,000 kg/ha).[23]Wholesaleprices can go as high as $18/bushel which is $0.60 per pound ($1.3/kg).[23]TheRegional IPM Centersprovideintegrated pest managementplans for use in the state.[23]

Production

[edit]In 2021, world production of okra was 10.8 milliontonnes,led byIndiawith 60% of the total, withNigeriaandMalias secondary producers.

| Okra production – 2021 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (Millions oftonnes) |

| 6.47 | |

| 1.92 | |

| 0.67 | |

| 0.32 | |

| 0.26 | |

| World | 10.82 |

| Source:FAOSTAT[25] | |

Uses

[edit]Nutrition

[edit]Raw okra contains 90% water, 2%protein,7%carbohydratesand negligiblefat.In a 100 gram reference amount, raw okra is a rich source (20% or more of theDaily Value,DV) ofdietary fiber,vitamin C,andvitamin K,with moderate contents ofthiamin,folateandmagnesium(table). Okra seeds are a source of protein and oil.[26]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 138 kJ (33 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

7.46 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 1.48 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fibre | 3.3 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.19 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.9 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 89.6 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated usingUS recommendationsfor adults,[27]except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation fromthe National Academies.[28] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Culinary

[edit]Okra is one of threethickenersthat may be used ingumbosoup fromLouisiana.[29]Fried okrais a dish from theCuisine of the Southern United States.InCubaandPuerto Rico,the vegetable is referred to asquimbombó,and is used in dishes such asquimbombó guisado(stewed okra), a dish similar to gumbo.[30][31]It is also used in traditional dishes in theDominican Republic,where it is calledmolondrón.[32]InBrazil,it is an important component of several regional dishes, such as Caruru, made with shrimp, in the Northeastern region, and Frango com Quiabo (Chicken with Okra) and Carne Refogada com Quiabo (Stewed meat with Okra) inMinas Gerais.

In South Asia, the pods are used in many spicy vegetable preparations as well as cooked with beef, mutton, lamb and chicken.[33][34]

Pods

[edit]

The pods of the plant aremucilaginous,resulting in the characteristic "goo" orslimewhen the seed pods are cooked; the mucilage containssoluble fiber.[35]One possible way to de-slime okra is to cook it with an acidic food, such as tomatoes, to minimize the mucilage.[36]Pods are cooked, pickled, eaten raw, or included in salads. Okra may be used indeveloping countriesto mitigatemalnutritionand alleviatefood insecurity.[35]

Leaves and seeds

[edit]Young okra leaves may be cooked similarly to the greens ofbeetsordandelions,or used in salads. Okra seeds may be roasted and ground to form a caffeine-free substitute forcoffee.[4]When importation of coffee was disrupted by theAmerican Civil Warin 1861, theAustin State Gazettesaid, "An acre of okra will produce seed enough to furnish aplantationwith coffee in every way equal to that imported fromRio."[37]

Greenish-yellow edible okraoilis pressed from okra seeds; it has a pleasant taste and odor, and is high inunsaturated fatssuch asoleic acidandlinoleic acid.[38]The oil content of some varieties of the seed is about 40%. At 794 kilograms per hectare (708 lb/acre), the yield was exceeded only by that ofsunflower oilin one trial.[39]

Industrial

[edit]Bast fibrefrom the stem of the plant has industrial uses such as thereinforcement of polymer composites.[40]The mucilage produced by the okra plant can be used for the removal ofturbidityfromwastewaterby virtue of itsflocculantproperties.[41][42]Having composition similar to a thickpolysaccharide film,okra mucilage is under development as abiodegradablefood packaging,as of 2018.[43]A 2009 study found okra oil suitable for use as abiofuel.[44]

Gallery

[edit]-

Large okra plants

-

A giant okra pod

-

Flower close-up

-

Stamen and pollen

-

Young seedling showingcotyledons

-

Fresh-picked fruits

-

Bhindi bharta, a South Asian dish

References

[edit]- ^"The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species".Retrieved3 October2014.

- ^"Okra".BBC Good Food.Retrieved2023-04-12.

- ^Ayto, John, ed. (2002)."lady's fingers".An A-Z of Food and Drink.Oxford University Press.ISBN9780192803511.Retrieved2023-04-12.

- ^abcd"Okra, or 'Gumbo,' from Africa".Texas AgriLife Extension Service, Texas A&M University. Archived fromthe originalon March 4, 2005.

- ^National Research Council (2006-10-27)."Okra".Lost Crops of Africa: Volume II: Vegetables.Vol. 2. National Academies Press.ISBN978-0-309-10333-6.Retrieved2008-07-15.

- ^"Definition ofAbelmoschus".Merriam-Webster Dictionary.Retrieved2020-06-23.

- ^"Latin definition for esculentus, esculenta, esculentum (ID: 19365)".Latin Dictionary and Grammar Resources - Latdict. 2020.Retrieved2020-06-23.

- ^"Definition ofokra".Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2020.Retrieved2020-06-23.

- ^Justin Vogt (2009-12-29)."Gumbo: The mysterious history".The Atlantic.Retrieved2020-06-23.

- ^"Definition ofgumbo".Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2020.Retrieved2020-06-23.

- ^"Many food names in English come from Africa".VOA.2018-02-06.Retrieved2020-06-23.

- ^Stanley Dry (2020)."A short history of gumbo".Southern Foodways Alliance.Retrieved2020-06-23.

- ^Patel, S. R."GENETIC ADVANCE UNDER SELECTION IN SEGREGATING POPULATION IN OKRA (Abelmoschus esculentus L.)".AGRES – an International E. Journal.

- ^Vegetables.Wageningen, Netherlands: Backhuys. 2004. p. 21.ISBN9057821478.

- ^Muimba-Kankolongo, Ambayeba (2018)."Okra: Vegetable Production - Origin and Geographic Distribution".Science Direct.

- ^Blench, R. (2006).Archaeology, Language, and the African Past.Rowman Altamira. p. 237.ISBN978-0-7591-0466-2.

- ^"Okra - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics".www.sciencedirect.com.Retrieved2021-11-09.

- ^"Okra, Gumbo, & Rice".unesdoc.unesco.org.

- ^"Colonial Food In Philadelphia - 1883 Words | Internet Public Library".www.ipl.org.Retrieved2021-11-09.

- ^abAlmanac, Old Farmer's."Okra".Old Farmer's Almanac.Retrieved2021-04-29.

- ^Kurt Nolte."Okra seed"(PDF).Yuma County Cooperative Extension. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2014-10-31.Retrieved2012-10-17.

- ^Plant breeding, Chapter 9.2(PDF).Strategies For Enhancement in Food Production. 2020.

- ^abcde"Southern Florida 2005 Okra PMSP".Regional Integrated Pest Management CentersDatabase. 2022-05-04.Retrieved2022-06-30.

- ^Aguiar, José L; McGiffen, Milt; Natwick, Eric; Takele, Etaferahu (2011).Okra Production in California.University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources(UCANR). p. 3.doi:10.3733/ucanr.7210.ISBN978-1-60107-002-9.7210.

- ^"Production: Crops and livestock products: World, Production Quantity, Okra, 2021 (from pick lists)".Food and Agriculture Organization,Statistics Division. 2021.Retrieved19 February2023.

- ^Gemede, Habtamu Fekadu (2015)."Nutritional Quality and Health Benefits of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus): A Review".Journal of Food Processing & Technology.06(6).doi:10.4172/2157-7110.1000458.ISSN2157-7110.

- ^United States Food and Drug Administration(2024)."Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels".FDA.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-03-27.Retrieved2024-03-28.

- ^National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.).Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium.The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).ISBN978-0-309-48834-1.PMID30844154.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-05-09.Retrieved2024-06-21.

- ^Gutierrez, C. Paige (1992).Cajun Foodways.University Press of Mississippi. p. 56.ISBN978-0-87805-563-0.

- ^Julie Schwietert Collazo."Cuban Quimbombo (Afro-Cuban Okra)".The Latin Kitchen. Archived fromthe originalon 2020-10-23.Retrieved2020-10-21.

- ^Gloria Cabada-Leman (22 June 2008)."QUIMBOMBÓ GUISADO".whats4eats.Retrieved2020-10-21.

- ^"El intrépido molondrón"(in Spanish). Diario Libre. 15 August 2012.Retrieved2022-08-29.

- ^Willis, Virginia (2014).Okra: a Savor the South cookbook.University of North Carolina Press. pp. 75–82.ISBN978-1-4696-1442-7.Retrieved22 December2021.

- ^Taylor Sen, Colleen (2004).Food culture in India.Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 60, 150.ISBN0-313-32487-5.Retrieved22 December2021.

- ^abGemede, H. F.; Haki, G. D.; Beyene, F; Woldegiorgis, A. Z.; Rakshit, S. K. (2015)."Proximate, mineral, and antinutrient compositions of indigenous Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) pod accessions: Implications for mineral bioavailability".Food Science & Nutrition.4(2): 223–33.doi:10.1002/fsn3.282.PMC4779480.PMID27004112.

- ^Jill Neimark (5 September 2018)."Leave it to botanists to turn cooking into a science lesson".US National Public Radio.Retrieved26 June2020.

- ^Austin State Gazette [TEX.], November 9, 1861, p. 4, c. 2, copied inConfederate Coffee Substitutes: Articles from Civil War NewspapersArchivedSeptember 28, 2007, at theWayback Machine,University of Texas at Tyler

- ^Martin, Franklin W. (1982). "Okra, Potential Multiple-Purpose Crop for the Temperate Zones and Tropics".Economic Botany.36(3): 340–345.Bibcode:1982EcBot..36..340M.doi:10.1007/BF02858558.S2CID38546395.

- ^Mays, D A, Buchanan, W, Bradford, B N, Giordano, P M (1990). "Fuel production potential of several agricultural crops".Advances in New Crops:260–263.

- ^De Rosa, I.M.; Kenny, J.M.; Puglia, D.; Santulli, C.; Sarasini, F. (2010). "Morphological, thermal and mechanical characterization of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) fibres as potential reinforcement in polymer composites ".Composites Science and Technology.70(1): 116–122.doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2009.09.013.

- ^Konstantinos Anastasakis; Dimitrios Kalderis; Evan Diamadopoulos (2009), "Flocculation behavior of mallow and okra mucilage in treating wastewater",Desalination,249(2): 786–791,Bibcode:2009Desal.249..786A,doi:10.1016/j.desal.2008.09.013

- ^Monika Agarwal; Rajani Srinivasan; Anuradha Mishra (2001), "Study on Flocculation Efficiency of Okra Gum in Sewage Waste Water",Macromolecular Materials and Engineering,286(9): 560–563,doi:10.1002/1439-2054(20010901)286:9<560::AID-MAME560>3.0.CO;2-B

- ^Araújo, Antonio; Galvão, Andrêssa; Filho, Carlos Silva; Mendes, Francisco; Oliveira, Marília; Barbosa, Francisco; Filho, Men Sousa; Bastos, Maria (2018). "Okra mucilage and corn starch bio-based film to be applied in food".Polymer Testing.71:352–361.doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2018.09.010.ISSN0142-9418.S2CID139366820.

- ^Farooq, Anwar; Umer Rashid; Muhammad Ashraf; Muhammad Nadeem (March 2010). "Okra (Hibiscus esculentus) seed oil for biodiesel production".Applied Energy.87(3): 779–785.Bibcode:2010ApEn...87..779A.doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2009.09.020.