Orange (fruit)

Anorange,also calledsweet orangeto distinguish it from thebitter orange(Citrus × aurantium), is thefruitof a tree in thefamilyRutaceae.Botanically, this is the hybridCitrus×sinensis,between thepomelo(Citrus maxima) and themandarin orange(Citrus reticulata). Thechloroplastgenome,and therefore the maternal line, is that of pomelo. The sweet orange has had its fullgenome sequenced.

The orange originated in a region encompassingSouthern China,Northeast India,andMyanmar;the earliest mention of the sweet orange was inChinese literaturein 314 BC. Orange trees are widely grown for their sweet fruit. The fruit of theorange treecan be eaten fresh, or processed for its juice or fragrantpeel.In 2022, 76 milliontonnesof oranges were grown worldwide, withBrazilproducing 22% of the total, followed byIndiaandChina.

Oranges have featured in human culture since ancient times. They first appear in Western art in theArnolfini PortraitbyJan van Eyck,but they had been depicted in Chinese art centuries earlier, as in Zhao Lingrang'sSong dynastyfan paintingYellow Oranges and Green Tangerines.By the 17th century, an orangery had become an item of prestige in Europe, as seen at theVersailles Orangerie.More recently, artists such asVincent van Gogh,John Sloan,andHenri Matisseincluded oranges in their paintings.

Description

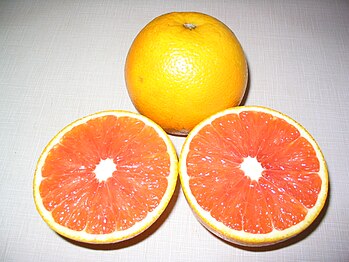

The orange tree is a relatively smallevergreen,floweringtree, with an average height of 9 to 10 m (30 to 33 ft), although some very old specimens can reach 15 m (49 ft).[1]Its ovalleaves,which arealternately arranged,are 4 to 10 cm (1.6 to 3.9 in) long and havecrenulatemargins.[2]Sweet oranges grow in a range of different sizes, and shapes varying from spherical to oblong. Inside and attached to the rind is a porous white tissue, the white, bittermesocarpor albedo (pith).[3]The orange contains a number of distinctcarpels(segments or pigs, botanically the fruits) inside, typically about ten, each delimited by a membrane and containing manyjuice-filled vesiclesand usually a fewpips.When unripe, the fruit is green. The grainy irregular rind of the ripe fruit can range from bright orange to yellow-orange, but frequently retains green patches or, under warm climate conditions, remains entirely green. Like all other citrus fruits, the sweet orange is non-climacteric,not ripening off the tree. TheCitrus sinensisgroup is subdivided into four classes with distinct characteristics: common oranges, blood or pigmented oranges, navel oranges, and acidless oranges.[4][5][6]The fruit is ahesperidium,a modifiedberry;it is covered by arindformed by a rugged thickening of theovary wall.[7][8]

-

Flowers

-

Fruit starting to develop

-

Flowers and fruit simultaneously

-

Mature tree inGalicia, Spain,fruiting in November

-

Structure of the botanicalhesperidium

History

Hybrid origins

Citrustrees areangiosperms,and most species are almost entirelyinterfertile.This includesgrapefruits,lemons,limes,oranges, and manycitrus hybrids.As the interfertility of oranges and other citrus has produced numerous hybrids andcultivars,andbud mutationshave also been selected,citrus taxonomyhas proven difficult.[9]

The sweet orange,Citrus x sinensis,[10]is not a wild fruit, but arose indomesticationin East Asia. It originated in a region encompassingSouthern China,Northeast India,[11]andMyanmar.[12] The fruit was created as a cross between a non-puremandarin orangeand a hybridpomelothat had a substantial mandarin component.[13][14]Since itschloroplast DNAis that of pomelo, it was likely the hybrid pomelo, perhaps a pomeloBC1 backcross,that was the maternal parent of the first orange.[15][16]Based on genomic analysis, the relative proportions of the ancestral species in the sweet orange are approximately 42% pomelo and 58% mandarin.[17]All varieties of the sweet orange descend from this prototype cross, differing only by mutations selected for during agricultural propagation.[16]Sweet oranges have a distinct origin from the bitter orange, which arose independently, perhaps in the wild, from a cross between pure mandarin and pomelo parents.[16]

Sweet oranges have in turn given rise to many further hybrids including thegrapefruit,which arose from a sweet orange x pomelo backcross. Spontaneous and engineered backcrosses between the sweet orange and mandarin oranges or tangerines have produced theclementineandmurcott.The ambersweet is a complex sweet orange x (Orlandotangelox clementine) hybrid.[17][18]Thecitrangesare a group of sweet orange xtrifoliate orange(Citrus trifoliata) hybrids.[19]

Arab Agricultural Revolution

In Europe, theMoorsintroduced citrus fruits including the bitter orange, lemon, and lime toAl-Andalusin theIberian Peninsuladuring theArab Agricultural Revolution.[20]Large-scale cultivation started in the 10th century, as evidenced by complex irrigation techniques specifically adapted to support orange orchards.[21][20]Citrus fruits—among them the bitter orange—were introduced to Sicily in the 9th century during the period of theEmirate of Sicily,but the sweet orange was unknown there until the late 15th century or the beginnings of the 16th century, when Italian and Portuguese merchants brought orange trees into the Mediterranean area.[11]

Spread across Europe

Shortly afterward, the sweet orange quickly was adopted as an edible fruit. It was considered a luxury food grown by wealthy people in private conservatories, calledorangeries.By 1646, the sweet orange was well known throughout Europe; it went on to become the most often cultivated of all fruit trees.[11]Louis XIVof France had a great love of orange trees and built the grandest of all royalOrangeriesat thePalace of Versailles.[22]At Versailles, potted orange trees in solid silver tubs were placed throughout the rooms of the palace, while the Orangerie allowed year-round cultivation of the fruit to supply the court. When Louis condemned his finance minister,Nicolas Fouquet,in 1664, part of the treasures that he confiscated were over 1,000 orange trees from Fouquet's estate atVaux-le-Vicomte.[23]

To the Americas

Spanish travelers introduced the sweet orange to the American continent. On his second voyage in 1493,Christopher Columbusmay have planted the fruit onHispaniola.[6]Subsequent expeditions in the mid-1500s brought sweet oranges to South America and Mexico, and to Florida in 1565, whenPedro Menéndez de AvilésfoundedSt Augustine.Spanish missionariesbrought orange trees to Arizona between 1707 and 1710, while theFranciscansdid the same in San Diego, California, in 1769.[11]Archibald Menzies,the botanist on theVancouver Expedition,collected orange seeds in South Africa, raised the seedlings onboard, and gave them to several Hawaiian chiefs in 1792. The sweet orange came to be grown across theHawaiian Islands,but its cultivation stopped after the arrival of theMediterranean fruit flyin the early 1900s.[11][24]Floridafarmers obtained seeds from New Orleans around 1872, after which orange groves were established by grafting the sweet orange on to sour orange rootstocks.[11]

Etymology

The word "orange" derives ultimately fromProto-DravidianorTamilநாரம்(nāram). From there the word enteredSanskritनारङ्ग(nāraṅga), meaning 'orange tree'. The Sanskrit word reachedEuropean languagesthroughPersianنارنگ(nārang) and itsArabicderivativeنارنج(nāranj).[25]

The word enteredLate Middle Englishin the 14th century viaOld Frenchpomme d'orenge.[26]Other forms includeOld Provençalauranja,[27]Italianarancia,formerlynarancia.[25]In several languages, the initialnpresent in earlier forms of the word dropped off because it may have been mistaken as part of an indefinite article ending in annsound. In French, for example,une norengemay have been heard asune orenge.This linguistic change is calledjuncture loss.The colorwas named after the fruit,[28]with the first recorded use oforangeas a color name in English in 1512.[29][30]

Composition

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 197 kJ (47 kcal) |

11.75 g | |

| Sugars | 9.35 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2.4 g |

0.12 g | |

0.94 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 1% 11 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 7% 0.087 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 3% 0.04 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 2% 0.282 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 5% 0.25 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 4% 0.06 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 8% 30 μg |

| Choline | 2% 8.4 mg |

| Vitamin C | 59% 53.2 mg |

| Vitamin E | 1% 0.18 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 3% 40 mg |

| Iron | 1% 0.1 mg |

| Magnesium | 2% 10 mg |

| Manganese | 1% 0.025 mg |

| Phosphorus | 1% 14 mg |

| Potassium | 6% 181 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.07 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 86.75 g |

| †Percentages estimated usingUS recommendationsfor adults,[31]except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation fromthe National Academies.[32] | |

Orange flesh is 87% water, 12%carbohydrates,1%protein,and contains negligiblefat(see table). As a 100 gram reference amount, orange flesh provides 47calories,and is a rich source ofvitamin C,providing 64% of theDaily Value.No othermicronutrientsare present in significant amounts (see table).

Phytochemicals

Oranges contain diversephytochemicals,includingcarotenoids(beta-carotene,luteinandbeta-cryptoxanthin),flavonoids(e.g.naringenin)[33]and numerousvolatile organic compoundsproducing orangearoma,includingaldehydes,esters,terpenes,alcohols,andketones.[34]Orange juice contains only about one-fifth thecitric acidoflimeorlemonjuice (which contain about 47 g/L).[35]

Taste

The taste of oranges is determined mainly by the ratio of sugars to acids, whereas orange aroma derives fromvolatile organic compounds,includingalcohols,aldehydes,ketones,terpenes,andesters.[36][37]Bitterlimonoidcompounds, such aslimonin,decrease gradually during development, whereas volatile aroma compounds tend to peak in mid– to late–season development.[38]Taste quality tends to improve later in harvests when there is a higher sugar/acid ratio with less bitterness.[38]As a citrus fruit, the orange is acidic, withpHlevels ranging from 2.9[39]to 4.0.[39][40]Taste and aroma vary according to genetic background, environmental conditions during development, ripeness at harvest, postharvest conditions, and storage duration.[36][37]

Cultivars

Common

Common oranges (also called "white", "round", or "blond" oranges) constitute about two-thirds of all orange production. The majority of this crop is used for juice.[4][6]

Valencia

The Valencia orange is a late-season fruit; it is popular when navel oranges are out of season.Thomas Rivers,an English nurseryman, imported this variety from theAzoresand catalogued it in 1865 under the name Excelsior. Around 1870, he provided trees to S. B. Parsons, aLong Islandnurseryman, who in turn sold them to E. H. Hart ofFederal Point, Florida.[41]

Navel oranges have a characteristic second fruit at theapex,which protrudes slightly like a humannavel.They are mainly an eating fruit, as their thicker skin makes them easy to peel, they are less juicy and their bitterness makes them less suitable for juice.[4]The parent variety was probably the Portuguese navel orange orUmbigodescribed byAntoine RissoandPierre Antoine Poiteauin their 1818–1822 bookHistoire naturelle des orangers( "Natural History of Orange Trees" ).[42]The mutation caused the orange to develop a second fruit at its base, opposite the stem, embedded within the peel of the primary orange. Navel oranges were introduced in Australia in 1824 and in Florida in 1835. In 1873,Eliza Tibbetsplanted two cuttings of the original tree inRiverside, California,where the fruit became known as "Washington".[42][43]The cultivar rapidly spread to other countries, but being seedless it had to be propagated bycuttingandgrafting.[44]

TheCara cara orangeis a type of navel orange grown mainly inVenezuela,South Africaand California'sSan Joaquin Valley.It is sweet and low in acid,[45]with distinctively pinkish red flesh. It was discovered at theHaciendaCara Cara inValencia,Venezuela, in 1976.[46]

Blood

Blood oranges, with an intense red coloration inside, are widely grown around the Mediterranean; there are several cultivars.[11]The development of the red color requires cool nights.[47]The redness is mainly due to theanthocyaninpigmentchrysanthemin(cyanidin 3-O-glucoside).[48]

Acidless

Acidless oranges are an early-season fruit with very low levels of acid. They also are called "sweet" oranges in the United States, with similar names in other countries:doucein France,sucrenain Spain,dolceormaltesein Italy,meskiin North Africa and the Near East (where they are especially popular),succariin Egypt, andlimain Brazil.[4]The lack of acid, which protects orange juice against spoilage in other groups, renders them generally unfit for processing as juice, so they are primarily eaten. They remain profitable in areas of local consumption, but rapid spoilage renders them unsuitable for export to major population centres of Europe, Asia, or the United States.[4]

-

A grove ofValencia orangesinFlorida

Cultivation

Climate

Like most citrus plants, oranges do well under moderate temperatures—between 15.5 and 29 °C (59.9 and 84.2 °F)—and require considerable amounts of sunshine and water. As oranges are sensitive tofrost,farmers have developed methods to protect the trees from frost damage. A common process is to spray the trees with water so as to cover them with a thin layer of ice, insulating them even if air temperatures drop far lower. This practice, however, offers protection only for a very short time.[49]Another procedure involves burning fuel oil insmudge potsput between the trees. These burn with a great deal of particulate emission, so condensation of water vapour on the particulate soot prevents condensation on plants and raises the air temperature very slightly. Smudge pots were developed after a disastrous freeze in southern California in January 1913 destroyed a whole crop.[50]

Propagation

Commercially grown orange trees arepropagatedasexuallybygraftinga maturecultivaronto a suitableseedlingrootstockto ensure the sameyield,identical fruit characteristics, and resistance to diseases throughout the years. Propagation involves two stages: first, a rootstock is grown from seed. Then, when it is approximately one year old, the leafy top is cut off and abudtaken from a specificscionvariety, is grafted into its bark. The scion is what determines the variety of orange, while the rootstock makes the tree resistant to pests and diseases and adaptable to specificsoiland climatic conditions. Thus, rootstocks influence the rate of growth and have an effect on fruit yield and quality.[51]Rootstocks must be compatible with the variety inserted into them because otherwise, the tree may decline, be less productive, or die.[51]Among the advantages to grafting are that trees mature uniformly and begin to bear fruit earlier than those reproduced by seeds (3 to 4 years in contrast with 6 to 7 years),[52]and that farmers can combine the best attributes of a scion with those of a rootstock.[53]

Harvest

Canopy-shaking mechanical harvesters are being used increasingly in Florida to harvest oranges. Current canopy shaker machines use a series of six-to-seven-foot-long tines to shake the tree canopy at a relatively constant stroke and frequency.[54]Oranges are picked once they are pale orange.[55]

Degreening

Oranges must be mature when harvested. In the United States, laws forbid harvesting immature fruit for human consumption in Texas, Arizona, California and Florida.[56]Ripe oranges, however, often have some green or yellow-green color in the skin.Ethylenegas is used to turn green skin to orange. This process is known as "degreening", "gassing", "sweating", or "curing".[56]Oranges are non-climactericfruits and cannot ripen internally in response to ethylene gas after harvesting, though they will de-green externally.[57]

Storage

Commercially, oranges can be stored by refrigeration in controlled-atmosphere chambers for up to twelve weeks after harvest. Storage life ultimately depends on cultivar, maturity, pre-harvest conditions, and handling.[58]At home, oranges have a shelf life of about one month, and are best stored loose.[59]

-

Spraying oranges in an orchard in Australia

-

Orange grove inCalifornia

-

Picking oranges, Israel

-

Harvest, Israel

-

Market stall, Morocco

Pests and diseases

Pests

The first major pest that attacked orange trees in the United States was the cottony cushion scale (Icerya purchasi), imported from Australia to California in 1868. Within 20 years, it wiped out the citrus orchards around Los Angeles, and limited orange growth throughout California. In 1888, the USDA sent Alfred Koebele to Australia to study thisscale insectin its native habitat. He brought back with him specimens of an Australianladybird,Novius cardinalis(the Vedalia beetle), and within a decade the pest was controlled. This was one of the first successful applications ofbiological pest controlon any crop.[41]Theorange dogcaterpillar of the giant swallowtail butterfly,Papilio cresphontes,is a pest of citrus plantations in North America, where it eats new foliage and can defoliate young trees.[60]

Diseases

Citrus greening disease,caused by the bacteriumLiberobacter asiaticum,has been the most serious threat to orange production since 2010. It is characterized by streaks of different shades on the leaves, and deformed, poorly colored, unsavory fruit. In areas where the disease is endemic, citrus trees live for only five to eight years and never bear fruit suitable for consumption.[62]In the western hemisphere, the disease was discovered in Florida in 1998, where it has attacked nearly all the trees ever since. It was reported in Brazil by Fundecitrus Brasil in 2004.[62]As from 2009, 0.87% of the trees in Brazil's main orange growing areas (São Paulo and Minas Gerais) showed symptoms of greening, an increase of 49% over 2008.[63] The disease is spread primarily bypsyllidplant lice such as the Asian citrus psyllid (Diaphorina citriKuwayama), an efficientvectorof the bacterium.[61]Foliar insecticides reduce psyllid populations for a short time, but also suppress beneficial predatory ladybird beetles. Soil application ofaldicarbprovided limited control of Asian citrus psyllid, while drenches ofimidaclopridto young trees were effective for two months or more.[64]Management of citrus greening disease requires an integrated approach that includes use of clean stock, elimination of inoculum via voluntary and regulatory means, use of pesticides to control psyllid vectors in the citrus crop, and biological control of the vectors in non-crop reservoirs.[62]

Greasy spot, afungal diseasecaused by the ascomyceteMycosphaerella citri,produces leaf spots and premature defoliation, thus reducing the tree's vigour and yield.AscosporesofM. citriare generated inpseudotheciain decomposing fallen leaves.[65]

Production

| Production of oranges – 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Production (millions oftonnes) |

| 16.9 | |

| 10.2 | |

| 7.6 | |

| 4.8 | |

| 3.4 | |

| 3.1 | |

| World | 76.4 |

| Source:FAOSTATof theUnited Nations[66] | |

In 2022, world production of oranges was 76 milliontonnes,led byBrazilwith 22% of the total, followed by India, China, and Mexico.[66] TheUnited States Department of Agriculturehas establishedgradesfor Florida oranges, primarily for oranges sold as fresh fruit.[67]In the United States, groves are located mainly inFlorida,California,andTexas.[68]The majority of California's crop is sold as fresh fruit, whereas Florida's oranges are destined to juice products. TheIndian Riverarea of Florida produces high quality juice, which is often sold fresh and blended with juice from other regions, because Indian River trees yield sweet oranges but in relatively small quantities.[69]

Culinary use

Dessert fruit and juice

Oranges, whose flavor may vary fromsweettosour,are commonly peeled and eaten fresh raw as a dessert.Orange juiceis obtained by squeezing the fruit on a special tool (ajuicerorsqueezer) and collecting the juice in a tray or tank underneath. This can be made at home or, on a much larger scale, industrially.[70]Orange juice is a traded commodity on theIntercontinental Exchange.[71]Frozen orange juice concentrate is made from freshly squeezed and filtered juice.[72]

Marmalade

Oranges are made intojamin many countries; in Britain, bitterSeville orangesare used to makemarmalade.Almost the whole Spanish production is exported to Britain for this purpose. The entire fruit is cut up and boiled with sugar; the pith contributespectin,which helps the marmalade to set. The first recipe was by an Englishwoman,Mary Kettilby,in 1714. Pieces of peel were first added byJanet KeillerofDundeein the 1790s, contributing a distinctively bitter taste.[73]Orange peel contains the bitter substanceslimoneneandnaringin.[74][75]

Extracts

Zestis scraped from thecoloured outer part of the peel,and used as a flavoring and garnish in desserts andcocktails.[76]

Sweetorange oilis aby-productof the juice industry produced by pressing the peel. It is used for flavoring food and drinks; it is employed in the perfume industry and inaromatherapyfor itsfragrance.The oil consists of approximately 90%D-limonene, asolventused in household chemicals such as wood conditioners for furniture and—along with other citrus oils—detergents and hand cleansers. It is an efficient cleaning agent with a pleasant smell, promoted for being environmentally friendly and therefore, preferable to petrochemicals. It is, however, irritating to the skin and toxic to aquatic life.[77][78]

In human culture

Oranges have featured in human culture since ancient times. The earliest mention of the sweet orange inChinese literaturedates from 314 BC.[13]Larissa Pham, inThe Paris Review,notes that sweet oranges were available in China much earlier than in the West. She writes that Zhao Lingrang's fan paintingYellow Oranges and Green Tangerinespays attention not to the fruit's colour but the shape of the fruit-laden trees, and that Su Shi's poem on the same subject runs "You must remember, / the best scenery of the year, / Is exactly now, / when oranges turn yellow and tangerines green."[79]

The scholar Cristina Mazzoni has examined the multiple uses of the fruit in Italian art and literature, fromCatherine of Siena's sending of candied oranges toPope Urban,toSandro Botticelli's setting of his paintingPrimaverain an orange grove. She notes that oranges symbolised desire and wealth on the one hand, and deformity on the other, while in the fairy-stories of Sicily, they have magical properties.[80]Pham comments that theArnolfini PortraitbyJan van Eyckcontains in a small detail one of the first representations of oranges in Western art, the costly fruit perhaps traded by the merchant Arnolfini himself.[79]By the 17th century,orangerieswere added to great houses in Europe, both to enable the fruit to be grown locally and for prestige, as seen in theVersailles Orangeriecompleted in 1686.[81]

The Dutchpost-impressionistartistVincent van Goghportrayed oranges in paintings such as his 1889Still Life of Oranges and Lemons with Blue Glovesand his 1890A Child with Orange,both works late in his life. The American artist of theAshcan School,John Sloan,made a 1935 paintingBlond Nude with Orange, Blue Couch,whileHenri Matisse's last painting was his 1951Nude with Oranges;after that he only made cut-outs.[82]

-

Yellow Oranges and Green Tangerinesby Zhao Lingrang, Chinese fan painting from theSong dynasty,c. 1070–1100

-

Detail of theArnolfini PortraitbyJan van Eyck,1434

-

Detail ofPrimaverabySandro Botticelli,1482, set in an orange grove

-

Still life with oranges on a plate. PossiblyJacques LinardorLouise Moillon,1640

-

TheVersailles Orangerie,1686

-

Jean-Baptiste Oudry,The Orange Tree,1740

-

Still Life of Oranges and Lemons with Blue GlovesbyVincent van Gogh,1889

See also

- Banana,another fruit exported and consumed in large quantities

- List of citrus fruits

- List of culinary fruits

References

- ^Hodgson, Willard (1967–1989) [1943]."Chapter 4: Horticultural Varieties of Citrus".In Webber, Herbert John;revWalter Reuther and Harry W. Lawton (eds.).The Citrus Industry.Riverside, California: University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences. Archived fromthe originalon 2012-02-05.

- ^"Sweet Orange – Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck (pro. sp.) – Overview – Encyclopedia of Life".Encyclopedia of Life.Archivedfrom the original on 2010-12-04.Retrieved2011-01-18.

- ^"Pith dictionary definition – pith defined".www.yourdictionary.com.Archivedfrom the original on 2011-05-12.Retrieved2011-01-17.

- ^abcdeKimball, Dan A. (June 30, 1999).Citrus processing: a complete guide(2d ed.). New York: Springer. p. 450.ISBN978-0-8342-1258-9.

- ^Webber, Herbert John; Reuther, Walter; Lawton, Harry W. (1967–1989) [1903]."The Citrus Industry".Riverside, California:University of CaliforniaDivision of Agricultural Sciences. Archived fromthe originalon 2004-06-04.

- ^abcSauls, Julian W. (December 1998)."Home Fruit Production – Oranges".Texas A&M University.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2023.Retrieved30 November2012.

- ^Bailey, H. and Bailey, E. (1976).Hortus Third.Cornell UniversityMacMillan. N.Y. p. 275.

- ^"Seed and Fruits".esu.edu.Archived fromthe originalon 2010-11-14.

- ^Nicolosi, E.; Deng, Z. N.; Gentile, A.; La Malfa, S.; Continella, G.; Tribulato, E. (2000). "Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers".Theoretical and Applied Genetics.100(8): 1155–1166.doi:10.1007/s001220051419.S2CID24057066.

- ^"Citrus ×sinensis (L.) Osbeck (pro sp.) (maxima × reticulata) sweet orange".Plants.USDA.gov.Archived fromthe originalon May 12, 2011.

- ^abcdefgMorton, Julia F. (1987).Fruits of Warm Climates.pp. 134–142.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-05-26.Retrieved2020-05-05.

- ^Talon, Manuel; Caruso, Marco; Gmitter, Fred G. Jr. (2020).The Genus Citrus.Woodhead Publishing.p. 17.ISBN978-0128122174.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-03-16.Retrieved2020-05-05.

- ^abXu, Q.; Chen, L.L.; Ruan, X.; Chen, D.; Zhu, A.; Chen, C.; et al. (Jan 2013)."The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis)".Nature Genetics.45(1): 59–66.doi:10.1038/ng.2472.PMID23179022.

- ^Andrés García Lor (2013).Organización de la diversidad genética de los cítricos(PDF)(Thesis). p. 79.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2021-02-25.Retrieved2015-04-24.

- ^Velasco, R.; Licciardello, C. (2014)."A genealogy of the citrus family".Nature Biotechnology.32(7): 640–642.doi:10.1038/nbt.2954.PMID25004231.S2CID9357494.

- ^abcWu, G. Albert (2014)."Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pomelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication".Nature Biotechnology.32(7): 656–662.doi:10.1038/nbt.2906.PMC4113729.PMID24908277.

- ^abcWu, Guohong Albert; Terol, Javier; Ibanez, Victoria; López-García, Antonio; Pérez-Román, Estela; Borredá, Carles; et al. (2018)."Genomics of the origin and evolution ofCitrus".Nature.554(7692): 311–316.Bibcode:2018Natur.554..311W.doi:10.1038/nature25447.hdl:20.500.11939/5741.PMID29414943.and Supplement

- ^Bai, Jinhe; Baldwin, Elizabeth B.; Hearn, Jake; Driggers, Randy; Stover, Ed (2014)."Volatile Profile Comparison of USDA Sweet Orange-like Hybrids versus 'Hamlin' and 'Ambersweet'".HortScience.49(10): 1262–1267.doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.49.10.1262.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-07-21.Retrieved2018-03-18.

- ^"Trifoliate hybrids".University of California at Riverside, Givaudan Citrus Variety Collection.Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2022.Retrieved15 March2024.

- ^abWatson, Andrew M. (1974). "The Arab Agricultural Revolution and Its Diffusion, 700–1100".The Journal of Economic History.34(1): 8–35.doi:10.1017/S0022050700079602.JSTOR2116954.S2CID154359726.

- ^Trillo San José, Carmen (1 September 2003)."Water and landscape in Granada".University of Granada.Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2023.Retrieved7 January2017.

- ^Leroux, Jean-Baptiste (2002).The Gardens of Versailles.Thames & Hudson.p. 368.

- ^Mitford, Nancy(1966).The Sun King.Sphere Books.p. 11.

- ^Mau, Ronald; Kessing, Jayma Martin (April 2007)."Ceratitis capitata (Wiedemann)".University of Hawaii.Archivedfrom the original on 18 July 2012.Retrieved5 December2012.

- ^ab"orange (n.)".Online Etymology Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2024.Retrieved15 March2024.

- ^"Definition oforange".OEDonline (www.oxforddictionaries.com). Archived fromthe originalon May 11, 2013.

- ^"Definition oforange".Collins English Dictionary(collinsdictionary.com).Archivedfrom the original on 2013-04-03.Retrieved2012-12-05.

- ^Paterson, Ian (2003).A Dictionary of Colour: A Lexicon of the Language of Colour(1st paperback ed.). London: Thorogood (published 2004). p. 280.ISBN978-1-85418-375-0.OCLC60411025.

- ^"orange colour".Oxford English Dictionary(Online ed.).Oxford University Press.(Subscription orparticipating institution membershiprequired.)

- ^Maerz, Aloys John; Morris, Rea Paul (1930),A Dictionary of Color,New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 200

- ^United States Food and Drug Administration(2024)."Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels".FDA.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-03-27.Retrieved2024-03-28.

- ^National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.).Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium.The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).ISBN978-0-309-48834-1.PMID30844154.Archivedfrom the original on 2024-05-09.Retrieved2024-06-21.

- ^Aschoff, Julian K.; Kaufmann, Sabrina; Kalkan, Onur; Neidhart, Sybille; Carle, Reinhold; Schweiggert, Ralf M. (2015-01-21). "In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids, Flavonoids, and Vitamin C from Differently Processed Oranges and Orange Juices [ Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck]".Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.63(2): 578–587.doi:10.1021/jf505297t.ISSN0021-8561.

- ^Perez-Cacho, P.R.; Rouseff, R.L. (2008). "Fresh squeezed orange juice odor: a review".Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr.48(7): 681–95.doi:10.1080/10408390701638902.PMID18663618.S2CID32567584.

- ^Penniston, Kristina L.; Nakada, Stephen Y.; Holmes, Ross P.; Assimos, Dean G. (2008)."Quantitative Assessment of Citric Acid in Lemon Juice, Lime Juice, and Commercially-Available Fruit Juice Products".Journal of Endourology.22(3): 567–570.doi:10.1089/end.2007.0304.ISSN0892-7790.PMC2637791.PMID18290732.

- ^abTietel, Z.; Plotto, A.; Fallik, E.; Lewinsohn, E.; Porat, R. (2011). "Taste and aroma of fresh and stored mandarins".Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture.91(1): 14–23.Bibcode:2011JSFA...91...14T.doi:10.1002/jsfa.4146.PMID20812381.

- ^abEl Hadi, M. A.; Zhang, F. J.; Wu, F. F.; Zhou, C. H.; Tao, J (2013)."Advances in fruit aroma volatile research".Molecules.18(7): 8200–29.doi:10.3390/molecules18078200.PMC6270112.PMID23852166.

- ^abBai, J.; Baldwin, E. A.; McCollum, G.; Plotto, A.; Manthey, J. A.; Widmer, W. W.; Luzio, G.; Cameron, R. (2016)."Changes in Volatile and Non-Volatile Flavor Chemicals of" Valencia "Orange Juice over the Harvest Seasons".Foods.5(1): 4.doi:10.3390/foods5010004.PMC5224568.PMID28231099.

- ^abSinclair, Walton B.; Bartholomew, E.T.; Ramsey, R. C. (1945)."Analysis of the organic acids of orange juice"(PDF).Plant Physiology.20(1): 3–18.doi:10.1104/pp.20.1.3.PMC437693.PMID16653966.

- ^Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(July 16, 1999)."Outbreak of Salmonella Serotype Muenchen Infections Associated with Unpasteurized Orange Juice – United States and Canada, June 1999".Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.48(27): 582–585.PMID10428096.Archivedfrom the original on November 1, 2021.RetrievedSeptember 10,2017.

- ^abcCoit, John Eliot (1915).Citrus fruits: an account of the citrus fruit industry, with special reference to California requirements and practices and similar conditions.Macmillan.Retrieved2 October2011.

- ^ab"Washington".Citrus ID.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2024.Retrieved14 March2024.,citing amongst other sourcesRisso, A.; Poiteau, A. (1819–1822).Histoire Naturelle des Orangers.Paris: Audot.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-12-10.Retrieved2024-03-14.

- ^Saunders, William "Experimental Gardens and Grounds", in USDA,Yearbook of Agriculture1897, 180 ff; USDA,Yearbook of Agriculture1900, 64.

- ^"Commodity Fact Sheet: Citrus Fruits"(PDF).California Foundation for Agriculture in the Classroom.Archived(PDF)from the original on 16 August 2022.Retrieved14 March2024.

- ^"UBC Botanical Garden, Botany Photo of the Day".Archived fromthe originalon 2010-01-24.

- ^"Cara Cara navel orange".University of California, Riverside.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-04-25.Retrieved2011-01-20.

- ^McGee, Harold (2004).On food and cooking: the science and lore of the kitchen.New York: Scribner. p.376.ISBN0-684-80001-2.Archivedfrom the original on 2023-07-28.Retrieved2024-03-15.

- ^Felgines, C.; Texier, O.; Besson, C.; Vitaglione, P; Lamaison, J.-L.; Fogliano, V.; et al. (2008). "Influence of glucose on cyanidin 3-glucoside absorption in rats".Molecular Nutrition & Food Research.52(8): 959–64.doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700377.PMID18646002.

- ^"How Cold Can Water Get?".Argonne National Laboratory.2002-09-08.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-02-26.Retrieved2009-04-16.

- ^Moore, Frank Ensor (1995).Redlands Astride the Freeway: The Development of Good Automobile Roads.Redlands, California: Moore Historical Foundation. p. 9.ISBN978-0-914167-07-5.

- ^abLacey, Kevin (July 2012)."Citrus rootstocks for WA"(PDF).Government of WA. Department of Agriculture and Food. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2013-11-12.Retrieved30 November2012.

- ^Price, Martin."Citrus Propagation and Rootstocks".ultimatecitrus.com. Archived fromthe originalon 6 April 2018.Retrieved30 November2012.

- ^"Citrus Propagation. Research Program on Citrus Rootstock Breeding and Genetics".ars-grin.gov.Archived fromthe originalon 2010-05-28.

- ^Bora, G.; Hebel, M.; Lee, K. (2007-12-01)."In-situ measurement of the detachment force of individual oranges harvested by a canopy shaker harvesting machine"(PDF).Abstracts for the 2007 Joint Annual Meeting of the Florida State Horticulture Society.S2CID113761794.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-26.

- ^"Fresh Citrus Direct".freshcitrusdirect.wordpress.com. Archived fromthe originalon 2015-01-10.

- ^abWagner, Alfred B.; Sauls, Julian W."Harvesting and Pre-pack Handling".The Texas A&M University System.Archivedfrom the original on 4 January 2013.Retrieved29 November2012.

- ^Arpaia, Mary Lu; Kader, Adel A."Orange: Recommendations for Maintaining Postharvest Quality".UCDavisPostharvest Technology Center. Archived fromthe originalon 2013-12-06.Retrieved2013-12-12.

- ^Ritenour, M.A. (2004)."Orange. The Commercial Storage of Fruits, Vegetables, and Florist and Nursery Stocks"(PDF).USDA.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2012-01-27.

- ^"Home Storage Guide for Fresh Fruits & Vegetables. Canadian Produce Marketing Association"(PDF).cpma.ca.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2013-05-12.

- ^Mcauslane, Heather (May 2009)."Giant Swallowtail, Orangedog, Papilio cresphontes Cramer (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)".University of Florida.doi:10.32473/edis-in134-2009.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2024.Retrieved14 March2024.

- ^abKilliny, Nabil; Nehela, Yasser; George, Justin; Rashidi, Mahnaz; Stelinski, Lukasz L.; Lapointe, Stephen L. (2021-07-01)."Phytoene desaturase-silenced citrus as a trap crop with multiple cues to attract Diaphorina citri, the vector of Huanglongbing".Plant Science.308:110930.doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110930.ISSN0168-9452.PMID34034878.S2CID235203508.

- ^abcHalbert, Susan E.; Manjunath, Keremane L. (September 2004)."Asian citrus psyllids (Sternorrhyncha: Psyllidae) and greening disease of citrus: A literature review and assessment of risk in Florida".The Florida Entomologist.87(3): 330–353.doi:10.1653/0015-4040(2004)087[0330:ACPSPA]2.0.CO;2.ISSN0015-4040.S2CID56161727.

- ^"GAIN Report Number: BR9006"(PDF).USDA Foreign Agricultural Service. 18 June 2009. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-05-13.

- ^Qureshi, J.; Stansly, P. (2007-12-01)."Integrated approaches for managing the Asian citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri (Homoptera: Psyllidae) in Florida"(PDF).Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society.120:110–115.S2CID55798062.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2023-11-17.Retrieved2023-11-17.

- ^Mondal, S.N.; Morgan, K.T.; Timme, L.W. (June 2007)."Effect of Water Management and Soil Application of Nitrogen Fertilizers, Petroleum Oils, and Lime on Inoculum Production by Mycosphaerella citri, the Cause of Citrus Greasy Spot"(PDF).Abstracts for the 2007 Joint Annual Meeting of the Florida State Horticulture Society.S2CID113761794.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2011-07-26.

- ^ab"Orange production in 2022, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity/Year (pick lists)".UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database. 2024.Archivedfrom the original on 12 November 2016.Retrieved15 March2024.

- ^"United States Standards for Grades of Florida Oranges and Tangelos".USDA. February 1997. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-07-26.

- ^"Oranges: Production Map by State".United States Department of Agriculture.1 March 2017.Archivedfrom the original on 31 October 2021.Retrieved1 April2017.

- ^"History of the Indian River Citrus District".Indian River Citrus League.Archivedfrom the original on 1 November 2021.Retrieved27 November2012.

- ^"How orange juice is made".Discovery Networks International. 20 September 2022.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2023.Retrieved16 March2024.

- ^Lawson, Alex (27 October 2023)."The great orange juice trading rally – and why a big squeeze could lie ahead".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 22 November 2023.Retrieved16 March2024.

- ^Townsend, Chet (2012)."The Story of Florida Orange Juice: From the Grove to Your Glass".Archivedfrom the original on 18 April 2021.Retrieved14 March2024.

- ^Bateman, Michael (3 January 1993)."Hail marmalade, great chieftain o' the jammy race: Mrs Keiller of Dundee added chunks in the 1790s, thus finally defining a uniquely British gift to gastronomy".The Independent.Archivedfrom the original on 23 February 2016.Retrieved15 March2024.

- ^Barros, H.R.; Ferreira, T.A.; Genovese, M.I. (2012). "Antioxidant capacity and mineral content of pulp and peel from commercial cultivars of citrus from Brazil".Food Chemistry.134(4): 1892–8.doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.090.PMID23442635.

- ^Hasegawa, S.; Berhow, M. A.; Fong, C. H. (1996). "Analysis of Bitter Principles in Citrus".Fruit Analysis.Vol. 18. Berlin, Heidelberg:Springer.pp. 59–80.doi:10.1007/978-3-642-79660-9_4.ISBN978-3-642-79662-3.

- ^Bender, David(2009).Oxford Dictionary of Food and Nutrition(third ed.).Oxford University Press.p.215.ISBN978-0-19-923487-5.

- ^"D-Limonene".International Programme on Chemical Safety.April 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 2021-11-04.Retrieved2010-03-06.

- ^"(±)-1-methyl-4-(1-methylvinyl)cyclohexene".ECHA.January 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-10-29.Retrieved2019-01-22.

- ^abPham, Larissa (13 August 2019)."For the Love of Orange".The Paris Review.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2024.Retrieved14 March2024.

- ^Freedman, Paul (2019)."Review of Golden Fruit: A Cultural History of Oranges in Italy, by Cristina Mazzoni".Journal of Interdisciplinary History.50(1). Project MUSE: 129–130.

- ^Thacker, Christopher;Louis XIV(1972). ""La Manière de montrer les jardins de Versailles," by Louis XIV and Others ".Garden History.1(1): 49–69.doi:10.2307/1586442.ISSN0307-1243.JSTOR1586442.

- ^Michalska, Magda (23 December 2023)."The Scent of Orange in the Air: Paintings with Oranges".Daily Art Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2024.Retrieved14 March2024.

External links

Media related toCitrus sinensisat Wikimedia Commons

Media related toCitrus sinensisat Wikimedia Commons Data related toCitrus sinensisat Wikispecies

Data related toCitrus sinensisat Wikispecies- Citrus sinensisList of Chemicals (Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases),USDA,Agricultural Research Service.

- Oranges: Safe Methods to Store, Preserve, and Enjoy.(2006). University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. Accessed May 23, 2014.