Overexploitation

Overexploitation,also calledoverharvesting,refers to harvesting arenewable resourceto thepoint of diminishing returns.[2]Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to replenish. The term applies tonatural resourcessuch aswater aquifers,grazing pasturesandforests,wildmedicinal plants,fish stocksand otherwildlife.

Inecology,overexploitation describes one of the five main activities threatening globalbiodiversity.[3]Ecologists use the term to describe populations that are harvested at an unsustainable rate, given their natural rates of mortality and capacities for reproduction. This can result in extinction at the population level and even extinction of whole species. Inconservation biology,the term is usually used in the context of human economic activity that involves the taking of biological resources, or organisms, in larger numbers than their populations can withstand.[4]The term is also used and defined somewhat differently infisheries,hydrologyandnatural resource management.

Overexploitation can lead to resource destruction, includingextinctions.However, it is also possible for overexploitation to be sustainable, asdiscussed belowin the section on fisheries. In the context of fishing, the termoverfishingcan be used instead of overexploitation, as canovergrazinginstock management,overlogginginforest management,overdraftinginaquifermanagement, andendangered speciesin species monitoring. Overexploitation is not an activity limited to humans. Introduced predators and herbivores, for example, can overexploit nativefloraandfauna.

History[edit]

Concern about overexploitation is relatively recent, though overexploitation itself is not a new phenomenon. It has been observed for millennia. For example, ceremonial cloaks worn by the Hawaiian kings were made from themamobird; a single cloak used the feathers of 70,000 birds of this now-extinct species. Thedodo,a flightless bird fromMauritius,is another well-known example of overexploitation. As with many island species, it was naive about certain predators, allowing humans to approach and kill it with ease.[7]

From the earliest of times,huntinghas been an important human activity as a means of survival. There is a whole history of overexploitation in the form of overhunting. Theoverkill hypothesis(Quaternary extinction events) explains why themegafaunalextinctions occurred within a relatively short period. This can be traced tohuman migration.The most convincing evidence of this theory is that 80% of the North American large mammal species disappeared within 1000 years of the arrival of humans on the western hemisphere continents.[8]The fastest ever recorded extinction ofmegafaunaoccurred inNew Zealand,where by 1500 AD, just 200 years after settling the islands, ten species of the giantmoa birdswere hunted to extinction by theMāori.[5]A second wave of extinctions occurred later with European settlement.

In more recent times, overexploitation has resulted in the gradual emergence of the concepts ofsustainabilityandsustainable development,which has built on other concepts, such assustainable yield,[9]eco-development,[10][11]anddeep ecology.[12][13]

Overview[edit]

Overexploitation does not necessarily lead to the destruction of the resource, nor is it necessarily unsustainable. However,depletingthe numbers or amount of the resource can change its quality. For example,footstool palmis a wild palm tree found in Southeast Asia. Its leaves are used for thatching and food wrapping, and overharvesting has resulted in its leaf size becoming smaller.

Tragedy of the commons[edit]

In 1968, the journalSciencepublished an article byGarrett Hardinentitled "The Tragedy of the Commons".[14]It was based on a parable thatWilliam Forster Lloydpublished in 1833 to explain how individuals innocently acting in their own self interest can overexploit, and destroy, a resource that they all share.[15][pages needed]Lloyd described a simplified hypothetical situation based on medievalland tenurein Europe.Herderssharecommon landon which they are each entitled tograzetheir cows. In Hardin's article, it is in each herder's individual interest to graze each new cow that the herder acquires on the common land, even if thecarrying capacityof the common is exceeded, which damages the common for all the herders. The self-interested herder receives all of the benefits of having the additional cow, while all the herders share the damage to the common. However, all herders reach the same rational decision to buy additional cows and graze them on the common, which eventually destroys the common. Hardin concludes:

Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit—in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.[14]: 1244

In the course of his essay, Hardin develops the theme, drawing in many examples of latter day commons, such asnational parks,the atmosphere, oceans, rivers andfish stocks.The example of fish stocks had led some to call this the "tragedy of the fishers".[16]A major theme running through the essay is the growth ofhuman populations,with theEarth's finite resources being the general common.

The tragedy of the commons has intellectual roots tracing back toAristotle,who noted that "what is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it",[17]as well as toHobbesand hisLeviathan.[18]The opposite situation to a tragedy of the commons is sometimes referred to as atragedy of the anticommons:a situation in which rational individuals, acting separately, collectively waste a given resource by underutilizing it.

The tragedy of the commons can be avoided if it is appropriately regulated. Hardin's use of "commons" has frequently been misunderstood, leading Hardin to later remark that he should have titled his work "The tragedy of the unregulated commons".[19]

Sectors[edit]

Fisheries[edit]

Inwild fisheries,overexploitation oroverfishingoccurs when afish stockhas been fished down "below the size that, on average, would support the long-termmaximum sustainable yieldof the fishery ".[20]However, overexploitation can be sustainable.[21]

When a fishery starts harvesting fish from a previously unexploited stock, thebiomassof the fish stock will decrease, since harvesting means fish are being removed. For sustainability, the rate at which the fish replenish biomass through reproduction must balance the rate at which the fish are being harvested. If the harvest rate is increased, then the stock biomass will further decrease. At a certain point, the maximum harvest yield that can be sustained will be reached, and further attempts to increase the harvest rate will result in the collapse of the fishery. This point is called themaximum sustainable yield,and in practice, usually occurs when the fishery has been fished down to about 30% of the biomass it had before harvesting started.[22]

It is possible to fish the stock down further to, say, 15% of the pre-harvest biomass, and then adjust the harvest rate so the biomass remains at that level. In this case, the fishery is sustainable, but is now overexploited, because the stock has been run down to the point where the sustainable yield is less than it could be.

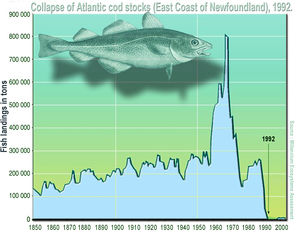

Fish stocks are said to "collapse" if their biomass declines by more than 95 percent of their maximum historical biomass.Atlantic codstocks were severely overexploited in the 1970s and 1980s, leading to their abrupt collapse in 1992.[1]Even though fishing has ceased, the cod stocks have failed to recover.[1]The absence of cod as theapex predatorin many areas has led totrophic cascades.[1]

About 25% of world fisheries are now overexploited to the point where their current biomass is less than the level that maximizes their sustainable yield.[23]These depleted fisheries can often recover if fishing pressure is reduced until the stock biomass returns to the optimal biomass. At this point, harvesting can be resumed near the maximum sustainable yield.[24]

Thetragedy of the commonscan be avoided within the context of fisheries iffishing effortand practices are regulated appropriately byfisheries management.One effective approach may be assigning some measure of ownership in the form ofindividual transferable quotas(ITQs) to fishermen. In 2008, a large scale study of fisheries that used ITQs, and ones that did not, provided strong evidence that ITQs help prevent collapses and restore fisheries that appear to be in decline.[25][26]

Water resources[edit]

Water resources, such aslakesandaquifers,are usually renewable resources which naturally recharge (the termfossil wateris sometimes used to describe aquifers which do not recharge). Overexploitation occurs if a water resource, such as theOgallala Aquifer,is mined or extracted at a rate that exceeds the recharge rate, that is, at a rate that exceeds the practical sustained yield. Recharge usually comes from area streams, rivers and lakes. An aquifer which has been overexploited is said to beoverdraftedor depleted. Forests enhance the recharge ofaquifersin some locales, although generally forests are a major source of aquifer depletion.[27][28]Depleted aquifers can become polluted with contaminants such asnitrates,or permanently damaged through subsidence or through saline intrusion from the ocean.

This turns much of the world's underground water and lakes into finite resources with peak usage debates similar tooil.[29][30]These debates usually centre around agriculture and suburban water usage but generation of electricity from nuclear energy or coal and tar sands mining is also water resource intensive.[31]A modifiedHubbert curveapplies to any resource that can be harvested faster than it can be replaced.[32]Though Hubbert's original analysis did not apply to renewable resources, their overexploitation can result in aHubbert-like peak.This has led to the concept ofpeak water.

Forestry[edit]

Forestsare overexploited when they areloggedat a rate faster thanreforestationtakes place. Reforestation competes with other land uses such as food production, livestock grazing, and living space for further economic growth. Historically utilization of forest products, including timber and fuel wood, have played a key role in human societies, comparable to the roles of water and cultivable land. Today, developed countries continue to utilize timber for building houses, and wood pulp forpaper.In developing countries almost three billion people rely on wood for heating and cooking.[33]Short-term economic gains made byconversion of forestto agriculture, or overexploitation of wood products, typically leads to loss of long-term income and long term biological productivity.West Africa,Madagascar,Southeast Asiaand many other regions have experienced lower revenue because of overexploitation and the consequent declining timber harvests.[34]

Biodiversity[edit]

Overexploitation is one of the main threats to globalbiodiversity.[3]Other threats includepollution,introducedandinvasivespecies,habitat fragmentation,habitat destruction,[3]uncontrolled hybridization,[35]climate change,[36]ocean acidification[37]and the driver behind many of these,human overpopulation.[38]

One of the key health issues associated with biodiversity is drug discovery and the availability of medicinal resources.[39]A significant proportion of drugs arenatural productsderived, directly or indirectly, from biological sources. Marine ecosystems are of particular interest in this regard.[40]However, unregulated and inappropriatebioprospectingcould potentially lead to overexploitation, ecosystem degradation andloss of biodiversity.[41][42][43]

Endangered and extinct species[edit]

Species from all groups of fauna and flora are affected by overexploitation.

All living organisms require resources to survive. Overexploitation of these resources for protracted periods can deplete natural stocks to the point where they are unable to recover within a short time frame. Humans have always harvested food and other resources they have needed to survive. Human populations, historically, were small, and methods of collection limited to small quantities. With an exponential increase inhuman population,expanding markets and increasing demand, combined with improved access and techniques for capture, are causing theexploitationof many species beyond sustainable levels.[44]In practical terms, if continued, it reduces valuable resources to such low levels that their exploitation is no longer sustainable and can lead to theextinctionof a species, in addition to having dramatic, unforeseeneffects,on theecosystem.[45]Overexploitation often occurs rapidly as markets open, utilising previously untapped resources, or locally used species.

This is more prevalent when looking atisland ecologyand the species that inhabit them, as islands can be viewed as the world in miniature. Islandendemicpopulations are more prone toextinctionfrom overexploitation, as they often exist at low densities with reduced reproductive rates.[46]A good example of this are island snails, such as the HawaiianAchatinellaand the French PolynesianPartula.Achatinelline snails have 15 species listed as extinct and 24 critically endangered[47]while 60 species of partulidae are considered extinct with 14 listed as critically endangered.[48]TheWCMChave attributed over-collecting and very low lifetime fecundity for the extreme vulnerability exhibited among these species.[49]

As another example, when the humblehedgehogwas introduced to the Scottish island ofUist,the population greatly expanded and took to consuming and overexploiting shorebird eggs, with drastic consequences for their breeding success. Twelve species ofavifaunaare affected, with some species numbers being reduced by 39%.[50]

Where there is substantial human migration, civil unrest, or war, controls may no longer exist. With civil unrest, for example in theCongoandRwanda,firearms have become common and the breakdown of food distribution networks in such countries leaves the resources of the natural environment vulnerable.[51]Animals are even killed as target practice, or simply to spite the government. Populations of large primates, such asgorillasandchimpanzees,ungulatesand other mammals, may be reduced by 80% or more by hunting, and certain species may be eliminated altogether.[52]This decline has been called thebushmeat crisis.

Vertebrates[edit]

Overexploitation threatens one-third of endangeredvertebrates,as well as other groups. Excluding edible fish, the illegaltrade in wildlifeis valued at $10 billion per year. Industries responsible for this include the trade inbushmeat,the trade inChinese medicine,and thefur trade.[53]The Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, orCITESwas set up in order to control and regulate the trade in endangered animals. It currently protects, to a varying degree, some 33,000 species of animals and plants. It is estimated that a quarter of the endangered vertebrates in the United States of America and half of the endangered mammals is attributed to overexploitation.[3][54]

Birds[edit]

Overall, 50 bird species that have become extinct since 1500 (approximately 40% of the total) have been subject to overexploitation,[55]including:

- Great Auk– the penguin-like bird of the north, was hunted for itsfeathers,meat, fat and oil.

- Carolina parakeet– The only parrot species native to the eastern United States, was hunted forcrop protectionand its feathers.

Mammals[edit]

- The international trade in fur:chinchilla,vicuña,giant otterand numerous cat species

Fish[edit]

Various[edit]

- Novelty pets:snakes, parrots, primates andbig cats[56]

- Chinese medicine:bears,tigers,rhinos,seahorses,Asian black bearandsaiga antelope[57]

Invertebrates[edit]

Plants[edit]

- Horticulturists:New Zealand mistletoe (Trilepidea adamsii),orchids,cactiand many other plant species

Cascade effects[edit]

Overexploitation of species can result in knock-on orcascade effects.This can particularly apply if, through overexploitation, a habitat loses itsapex predator.Because of the loss of the top predator, adramatic increasein theirpreyspecies can occur. In turn, the unchecked prey can then overexploit their own food resources until population numbers dwindle, possibly to the point of extinction.

A classic example of cascade effects occurred withsea otters.Starting before the 17th century and not phased out until 1911, sea otters were hunted aggressively for their exceptionally warm and valuable pelts, which could fetch up to $2500 US. This caused cascade effects through thekelp forestecosystems along the Pacific Coast of North America.[58]

One of the sea otters’ primary food sources is thesea urchin.When hunters caused sea otter populations to decline, anecological releaseof sea urchin populations occurred. The sea urchins then overexploited their main food source,kelp,creating urchin barrens, areas of seabed denuded of kelp, but carpeted with urchins. No longer having food to eat, the sea urchin becamelocally extinctas well. Also, since kelp forest ecosystems are homes to many other species, the loss of the kelp caused other cascade effects of secondary extinctions.[59]

In 1911, when only one small group of 32 sea otters survived in a remote cove, an international treaty was signed to prevent further exploitation of the sea otters. Under heavy protection, the otters multiplied and repopulated the depleted areas, which slowly recovered. More recently, with declining numbers of fish stocks, again due to overexploitation,killer whaleshave experienced a food shortage and have been observed feeding on sea otters, again reducing their numbers.[60]

See also[edit]

- Carrying capacity

- Common-pool resource

- Conservation biology

- Defaunation

- Deforestation

- Ecosystem management

- Exploitation of natural resources

- Extinction

- Human overpopulation

- Inverse commons

- Over-consumption

- Overpopulation in wild animals

- Paradox of enrichment

- Planetary boundaries

- Social dilemma

- Sustainability

- Tyranny of small decisions

References[edit]

- ^abcdFrank, Kenneth T.; Petrie, Brian; Choi, Jae S.; Leggett, William C. (2005). "Trophic Cascades in a Formerly Cod-Dominated Ecosystem".Science.308(5728): 1621–1623.Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1621F.doi:10.1126/science.1113075.PMID15947186.S2CID45088691.

- ^Ehrlich, Paul R.; Ehrlich, Anne H. (1972).Population, Resources, Environment: Issues in Human Ecology(2nd ed.).W. H. Freeman and Company.p. 127.ISBN0716706954.

- ^abcdWilcove, D. S.; Rothstein, D.; Dubow, J.; Phillips, A.; Losos, E. (1998)."Quantifying threats to imperiled species in the United States".BioScience.48(8): 607–615.doi:10.2307/1313420.JSTOR1313420.

- ^Oxford. (1996). Oxford Dictionary of Biology. Oxford University Press.

- ^abHoldaway, R. N.; Jacomb, C. (2000)."Rapid Extinction of the Moas (Aves: Dinornithiformes): Model, Test, and Implications"(PDF).Science.287(5461): 2250–2254.Bibcode:2000Sci...287.2250H.doi:10.1126/science.287.5461.2250.PMID10731144.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2013-05-27.

- ^Tennyson, A.; Martinson, P. (2006).Extinct Birds of New Zealand.Wellington, New Zealand: Te Papa Press.ISBN978-0-909010-21-8.

- ^Fryer, Jonathan (2002-09-14)."Bringing the dodo back to life".BBC News.Retrieved2006-09-07.

- ^Paul S. Martin

- ^Larkin, P. A. (1977). "An epitaph for the concept of maximum sustained yield".Transactions of the American Fisheries Society.106(1): 1–11.doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1977)106<1:AEFTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^Lubchenco, J. (1991). "The Sustainable Biosphere Initiative: An ecological research agenda".Ecology.72(2): 371–412.doi:10.2307/2937183.JSTOR2937183.S2CID53389188.

- ^Lee, K. N. (2001). "Sustainability, concept and practice of". In Levin, S. A. (ed.).Encyclopedia of Biodiversity.Vol. 5. San Diego, CA:Academic Press.pp. 553–568.ISBN978-0-12-226864-9.

- ^Naess, A. (1986). "Intrinsic value: Will the defenders of nature please rise?". In Soulé, M. E. (ed.).Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity.Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. pp. 153–181.ISBN978-0-87893-794-3.

- ^Sessions, G., ed. (1995).Deep Ecology for the 21st Century: Readings on the Philosophy and Practice of the New Environmentalism.Boston: Shambala Books.ISBN978-1-57062-049-2.

- ^abHardin, Garrett (1968)."The Tragedy of the Commons".Science.162(3859): 1243–1248.Bibcode:1968Sci...162.1243H.doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243.PMID5699198.Also available athttp://www.garretthardinsociety.org/articles/art_tragedy_of_the_commons.html.

- ^Lloyd, William Forster (1833).Two Lectures on the Checks to Population.Oxford University.Retrieved2016-03-13.

- ^Bowles, Samuel (2004).Microeconomics: Behavior, Institutions, and Evolution.Princeton University Press.pp.27–29.ISBN978-0-691-09163-1.

- ^Ostrom, E. (1992). "The rudiments of a theory of the origins, survival, and performance of common-property institutions". In Bromley, D. W. (ed.).Making the Commons Work: Theory, Practice and Policy.San Francisco: ICS Press.

- ^Feeny, D.; et al. (1990). "The Tragedy of the Commons: Twenty-two years later".Human Ecology.18(1): 1–19.doi:10.1007/BF00889070.PMID12316894.S2CID13357517.

- ^"Will commons sense dawn again in time?".The Japan Times Online.

- ^"NOAA fisheries glossary".repository.library.noaa.gov.NOAA.Retrieved2021-06-13.

- ^[Source?]

- ^Bolden, E.G., Robinson, W.L. (1999),Wildlife ecology and management4th ed. Prentice-Hall, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ.ISBN0-13-840422-4

- ^Grafton, R.Q.; Kompas, T.;Hilborn, R.W.(2007). "Economics of Overexploitation Revisited".Science.318(5856): 1601.Bibcode:2007Sci...318.1601G.doi:10.1126/science.1146017.PMID18063793.S2CID41738906.

- ^Rosenberg, A.A. (2003). "Managing to the margins: the overexploitation of fisheries".Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.1(2): 102–106.doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2003)001[0102:MTTMTO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^New Scientist: Guaranteed fish quotas halt commercial free-for-all

- ^A Rising Tide: Scientists find proof that privatising fishing stocks can avert a disasterThe Economist, 18th Sept, 2008.

- ^"Underlying Causes of Deforestation: UN Report".World Rainforest Movement.Archived fromthe originalon 2001-04-11.

- ^Conrad, C. (2008-06-21)."Forests of eucalyptus shadowed by questions".Arizona Daily Star.Archived fromthe originalon 2008-12-06.Retrieved2010-02-07.

- ^"World's largest aquifer going dry".U.S. Water News Online. February 2006. Archived fromthe originalon 2006-09-13.Retrieved2010-12-30.

- ^Larsen, J. (2005-04-07)."Disappearing Lakes, Shrinking Seas: Selected Examples".Earth Policy Institute. Archived fromthe originalon 2006-09-03.Retrieved2009-01-26.

- ^http://www.epa.gov/cleanrgy/water_resource.htm[permanent dead link]

- ^Palaniappan, Meena & Gleick, Peter H. (2008)."The World's Water 2008-2009 Ch 1"(PDF).Pacific Institute.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2009-03-20.Retrieved2009-01-31.

- ^http://atlas.aaas.org/pdf/63-66.pdfArchived2011-07-24 at theWayback MachineForest Products

- ^"Destruction of Renewable Resources".

- ^Rhymer, Judith M.; Simberloff, Daniel (1996). "Extinction by Hybridization and Introgression".Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics.27:83–109.doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.83.JSTOR2097230.

- ^Kannan, R.; James, D. A. (2009)."Effects of climate change on global biodiversity: a review of key literature"(PDF).Tropical Ecology.50(1): 31–39.ISSN0564-3295.Retrieved2014-05-21.

- ^Mora, C.; et al. (2013)."Biotic and Human Vulnerability to Projected Changes in Ocean Biogeochemistry over the 21st Century".PLOS Biology.11(10): e1001682.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001682.PMC3797030.PMID24143135.

- ^Dumont, E. (2012)."Estimated impact of global population growth on future wilderness extent"(PDF).Earth System Dynamics Discussions.3(1): 433–452.Bibcode:2012ESDD....3..433D.doi:10.5194/esdd-3-433-2012.

- ^(2006) "Molecular Pharming" GMO Compass Retrieved November 5, 2009, From"GMO Compass".Archived fromthe originalon 2013-05-03.Retrieved2010-02-04.

- ^Roopesh, J.; et al. (2008)."Marine organisms: Potential Source for Drug Discovery"(PDF).Current Science.94(3): 292.

- ^Dhillion, S. S.; Svarstad, H.; Amundsen, C.; Bugge, H. C. (September 2002). "Bioprospecting: Effects on Environment and Development".Ambio.31(6): 491–493.doi:10.1639/0044-7447(2002)031[0491:beoead]2.0.co;2.JSTOR4315292.PMID12436849.

- ^Cole, Andrew (2005)."Looking for new compounds in sea is endangering ecosystem".BMJ.330(7504): 1350.doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7504.1350-d.PMC558324.PMID15947392.

- ^"COHAB Initiative - on Natural Products and Medicinal Resources".Cohabnet.org. Archived fromthe originalon 2017-10-25.Retrieved2009-06-21.

- ^Redford 1992, Fitzgibonet al.1995, Cuarón 2001.

- ^Frankham, R.; Ballou, J. D.; Briscoe, D. A. (2002).Introduction to Conservation Genetics.New York:Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-63014-6.

- ^Dowding, J. E.; Murphy, E. C. (2001). "The Impact of Predation be Introduced Mammals on Endemic Shorebirds in New Zealand: A Conservation Perspective".Biological Conservation.99(1): 47–64.doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00187-7.

- ^"IUCN Red List".2003b.

- ^"IUCN Red List".2003c.Retrieved9 December2003.

- ^WCMC. (1992). McComb, J., Groombridge, B., Byford, E., Allan, C., Howland, J., Magin, C., Smith, H., Greenwood, V. and Simpson, L. (1992). World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Chapman and Hall.

- ^Jackson, D. B.; Fuller, R. J.; Campbell, S. T. (2004). "Long-term Population Changes Among Breeding Shorebirds in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, In Relation to Introduced Hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) ".Biological Conservation.117(2): 151–166.doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00289-1.

- ^Jones, R. F. (1990). "Farewell to Africa".Audubon.92:1547–1551.

- ^Wilkie, D. S.; Carpenter, J. F. (1999). "Bushmeat hunting in the Congo Basin: An assessment of impacts and options for migration".Biodiversity and Conservation.8(7): 927–955.doi:10.1023/A:1008877309871.S2CID27363244.

- ^Hemley 1994.

- ^Primack, R. B. (2002).Essentials of Conservation Biology(3rd ed.). Sunderland: Sinauer Associates.ISBN978-0-87893-719-6.

- ^The LUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2009).

- ^"THE EXOTIC PET-DEMIC/UK'S TICKING TIMEBOMB EXPOSED".Born Free Foundationand theRoyal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.September 2021.

- ^Collins, Nick (2012-04-12)."Chinese medicines contain traces of endangered animals".The Daily Telegraph.Archived fromthe originalon April 12, 2012.

- ^Estes, J. A.; Duggins, D. O.; Rathbun, G. B. (1989)."The ecology of extinctions in kelp forest communities".Conservation Biology.3(3): 251–264.doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.1989.tb00085.x.

- ^Dayton, P. K.; Tegner, M. J.; Edwards, P. B.; Riser, K. L. (1998). "Sliding baselines, ghosts, and reduced expectations in kelp forest communities".Ecol. Appl.8(2): 309–322.doi:10.1890/1051-0761(1998)008[0309:SBGARE]2.0.CO;2.

- ^Krebs, C. J. (2001).Ecology(5th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings.ISBN978-0-321-04289-7.

Further reading[edit]

- FAO(2005)Overcoming factors of unsustainability and overexploitation in fisheriesFisheries report 782, Rome.ISBN978-92-5-105449-9

- We’ve overexploited the planet, now we need to change if we’re to survive.Patrick VallanceforThe Guardian.July 8, 2022.