Parī

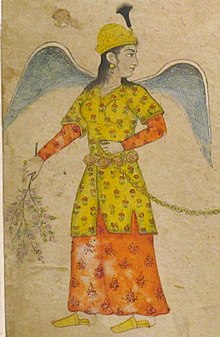

Parī,flying, with cup and wine flask in a miniature byŞahkulu | |

| Grouping | Mythical creature |

|---|---|

| Folklore | Pre-Islamic Persian folklore,Islamic folklore |

| Country | Muslim world |

Parīis a supernatural entity originating fromPersian talesand distributed into wider Asian folklore.[1]They are often described as winged creatures of immense beauty who are structured in societies similar to that of humans. Unlikejinn,theParīusually feature in tales involving supernatural elements.

Over time, the depiction ofparīwas subject to change and reconsideration. In early Persian beliefs, theparīwere probably a class of evil spirits and only later received a positive reception. In theIslamic period,theparīalready developed into morally complex beings with a generally positive connotation of immense beauty,[2][3]and late in the tenth century, were integrated into the Arabhouri-tale tradition. They are often contrasted by their nemesis the uglydīvs.

Despite their beauty, theparīare also feared because they are said to abduct people and take them to theirhome-world(Pariyestân) or punish people for social transgressions.

Etymology

[edit]The Persian wordپَریparīcomes fromMiddle Persianparīg,itself fromOld Persian*parikā-.[4]The word may stem from the same root as the Persian wordpar'wing',[5]although other proposed etymologies exist.[4]

The etymological relation to the English word "fairy" is disputed. Some argue that there is no relation and that both words derive from different meanings.[6]Others argue that both terms share a common origin:[7]The English term "fairy" deriving fromfier(enchant) and the Persian term frompar(enchant).[8]However, there is no consensus on either theory.

Persian literature

[edit]

Originally, theparīhave been considered a class ofdēvatāand the termdīvānahrefers to a person who lost reason because they fell in love, as the beloved steals the lover's reason.[9]In this regard, theparīfeatures similar to the Arabicjinn.[10]Thejinn,unlike theparī,do not have connotations of beauty however.[11]InMiddle Persian literature,comets have been identified withparī.Comets and planets were associated with evil, while the Sun, the Moon, and the fixed stars, with good.[12]Such negative associations of the planets, however, are not supported inAvestan languages.[13]

In popular literature of the Islamic period,parīare non-human beings with wings and magical powers. They are often, though not necessarily, female and employ an erotic appeal to mortal men.[14]As early as the tenth century,parīfeature as a template for the exquisite beauty of "the beloved" inPersianatefolklore and poetry, echoing an identification with the ArabicHouri.[5][15]However, the term has also been used as a synonym forjinn.[16][17][18]

At the start ofFerdowsi's epic poemShahnameh,"The Book of Kings", the divinitySorushappears in the form of aparīto warnKeyumars(the mythological first man andshahof the world) and his sonSiamakof the threats posed by the destructiveAhriman.Parīsalso form part of the mythological army that Keyumars eventually draws up to defeat Ahriman and his demonic son.[19]

In the stories ofOne Thousand and One Nights,aparīappears only in the story ofAhmad and Pari Bānu.The tale is a combination of originally two separate stories; theparīfeatures in the latter, when Prince Ahmad meets the beautiful princess Pari Banu. Ahmad has to deal with difficult tasks he manages to comply by aid of his fairy-wife.[20]

Folklore

[edit]

FromIndia,[21]across NorthernPakistan,Afghanistan,andIrantoCentral Asia,andTurkey,[22]local traditions variously acknowledge the existence of a supernatural creature calledparī.[23]The termparīis attested in Turkish sources from the 11th century onward[24]and was probably associated with the Arabicjinnwhen entering the Turkic beliefs through Islamic sources.[25]Althoughjinnandparīare sometimes used as synonyms, the termparīis more frequently used in supernatural tales.[26]According to the bookPeople of the Air,theparīare morally ambivalent creatures, and can be either Muslims or infidels.[27]

According to TurkologistIgnác Kúnos,theparīin Turkish tales fly through the air with cloud-like garments of a green colour, but also in the shape of doves. They also number forty, seven or three, and serve a Fairy-king that can be a human person they abducted from the human world. Like vestals, Kúnos wrote, theparībelong to the spiritual realm until love sprouts in their hearts, and they must join with their mortal lovers, being abandoned by their sisters to their own devices. Also, the first meeting between humans andparīoccurs during the latter's bathtime.[28]Theparīare usually considered benevolent in Turkish sources.[29]Shamans inKazakhstansometimes consultparīfor aid in spiritual rituals.[30]Uyghur shamansuse the aid ofparīto heal women frommiscarriage,and protect from evil jinn.[31]According to theKho,parīare able to castlove spells,sometimes used by a spiritual master referred to as "Master of Faries".[32]

Sometimes theparīwould take interest in the life of humans and abduct them to invite them to weddings of fellowparī.Alleged abductions can be either physical or psychological, in which case their victims lose consciousness. During the periods of abductions, people claim to be able to see, hear, and interact withparī,and sometimes even report their words and appearance.[33]

Parīwere the target of a lower level of evilDīvs(دیو), who persecuted them by locking them in iron cages.[34]This persecution was brought about by, as theDīvsperceived it, theparī'lack of sufficient self-esteem to join the rebellion against perversion.[35]

Islamic scripture and interpretations

[edit]Abu Ali Bal'ami's interpretation of theQiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾHistory of the Prophets and Kings,Godcreatesparīat some point after the viciousdīvs.[36]They ruled the world until it was given to a tribe of angels called al-jinn (fereštegan), those leader wasIblis.[37]Although theparīlose their rank as representatives of the earth after the creation ofAdam,they are still present during the time of Keyumar. It is only after thefloodthat they became hidden from the sight of humankind.[38]

Isma'ilitescholarNasir Khusraw(1004 – between 1072–1088) elaborates on the concept ofparīin his explanation of angels, jinn, and devils. He asserts thatparīis the Persian term forjinn.Then, he proceeds that theparīare divided into two categories: angel and devil. Eachparīwould be both a potential angel and a potential devil (dīv), depending on obedience or disobedience.[39]

Western representations

[edit]

Arthur de Gobineautells in his travel report about his 'three years in Asia' a story involvingFath-Ali Shah Qajarandparī.Shah Qajar is said to have had a strong inclination towards theOccultand had hold high respect for experts in the supernatural such asdarvīshes.One day adarvīshwarned him that the prince needs precautions to meet theparī.The affection ofparīmight soon turn into wrath, when he acted in a way which might offend him. He then prepares for a meeting at a pavilion outside the city. For the special occasion, the Garden was adorned with precious golden and silver vessels, jewellery, and costly furniture. After the sunset he fell asleep. When he woke up again, he found that there was that not only there was noparībut also that thedarvīshwas gone. The author of the tale was probably familarized with the tale on his travels toTehranat orders ofNapoleon IIIin 1855. The authors leaves a mark of mockery and used as a sign of the Persian's gullibility. Whether Gobineau's remark holds true or not, the story reflects the popularity of such belief in Iranian consciousness.[40]

InThomas Moore's poemParadise and the Peri,part of hisLalla-Rookh,a peri gains entrance to heaven after three attempts at giving anangelthe gift most dear to God. The first attempt is "The last libation Liberty draws/From the heart that bleeds and breaks in her cause", to wit, a drop ofbloodfrom a young soldier killed for an attempt on the life ofMahmud of Ghazni.Next is a "Precious sigh/of pure, self-sacrificing love": a sigh stolen from the dying lips of a maiden who died with her lover ofplaguein the Mountains of the Moon (Ruwenzori) rather than surviving in exile from the disease and the lover. The third gift, the one that gets the peri into heaven, is a "Tear that, warm and meek/Dew'd that repentant sinner's cheek": the tear of an evil old man who repented upon seeing a child praying in the ruins of theTemple of the Sunat Balbec,Syria.Robert Schumannset Moore's tale to music as an oratorio,Paradise and the Peri,using an abridgedGermantranslation.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Sherman, Josepha (2008).Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore.Sharpe Reference. p. 361.ISBN978-0-7656-8047-1.

- ^Abedinifard, Mostafa; Azadibougar, Omid; Vafa, Amirhossein, eds. (2021). Persian Literature as World Literature. Literatures as World Literature. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 37–43. ISBN 978-1-5013-5420-5

- ^Aigle, Denise.The Mongol Empire between Myth and Reality: Studies in Anthropological History.BRILL, 28.10.2014. p. 118.ISBN9789004280649.

- ^ab"PAIRIKĀ".Iranicaonline.org.

- ^abBoratav, P.N. and J.T.P. de Bruijn, “Parī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 31 January 2024 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0886> First published online: 2012 First print edition:ISBN978-90-04-16121-4,1960-2007

- ^Marzolph, Ulrich (08 Apr 2019). "The Middle Eastern World’s Contribution to Fairy-Tale History".In: Teverseon, Andrew.The Fairy Tale World.Routledge, 2019. pp. 46, 52, 53. Accessed on: 16 Dec 2021. https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315108407-4- "Turkish peri masalı is a literal translation of the term 'fairy tale,' the originally Indo–Persian character of the peri or pari constituting the equivalent of the European fairy in modern Persian folktales (Adhami 2010). [...] Probably the character most fascinating for a Western audience in the Persian tales is the peri or pari (Adhami 2010). Although the Persian word is tantalizingly close to the English 'fairy', both words do not appear to be etymologically related. English 'fairy' derives from Latin fatum, 'fate', via the Old French faerie, 'land of fairies'. The modern Persian word, instead, derives from the Avestan pairikā, a term probably denoting a class of pre-Zoroastrian goddesses who were concerned with sexuality and who were closely connected with sexual festivals and ritual orgies. In Persian narratives and folklore of the Muslim period, the peri is usually imagined as a winged character, most often, although not exclusively, of female sex, that is capable of acts of sorcery and magic (Marzolph 2012: 21–2). For the male hero, the peri exercises a powerful sexual attraction, although unions between a peri and a human man are often ill-fated, as the human is not able to respect the laws ruling the peri's world. The peri may at times use a feather coat to turn into a bird and is thus linked to the concept of the swan maiden that is wide-spread in Asian popular belief. If her human husband transgresses one of her taboos, such as questioning her enigmatic actions, the peri will undoubtedly leave him, a feature that is exemplified in the widely known European folktale tale type 400: 'The Man on a Quest for His Lost Wife' (Schmitt 1999)."

- ^Seyed‐Gohrab, Ali Asghar. "Magic in classical Persian amatory literature." Iranian Studies 32.1 (1999): 71-97.

- ^Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji. "An Account of Comets as given by Mahomedan Historians and as contained in the books of the Pishinigan or the Ancient Persians referred to by Abul Fazl." (1917): 68-105.

- ^Seyed‐Gohrab, Ali Asghar. "Magic in classical Persian amatory literature." Iranian Studies 32.1 (1999): 71-97.

- ^Seyed‐Gohrab, Ali Asghar. "Magic in classical Persian amatory literature." Iranian Studies 32.1 (1999): 71-97.

- ^Seyed‐Gohrab, Ali Asghar. "Magic in classical Persian amatory literature." Iranian Studies 32.1 (1999): 71-97.

- ^Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji. "An Account of Comets as given by Mahomedan Historians and as contained in the books of the Pishinigan or the Ancient Persians referred to by Abul Fazl." (1917): 68-105.

- ^Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji. "An Account of Comets as given by Mahomedan Historians and as contained in the books of the Pishinigan or the Ancient Persians referred to by Abul Fazl." (1917): 68-105.

- ^Marzolph, Ulrich, and Richard van Leeuwen. "The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful: The Survival of Ancient Iranian Ethical Concepts in Persian Popular Narratives of the Islamic Period." The Idea of Iran: Tradition and Innovation in Early Islamic Persia (2012): 16-29.

- ^Seyed‐Gohrab, Ali Asghar. "Magic in classical Persian amatory literature." Iranian Studies 32.1 (1999): 71-97.

- ^Shahbazi, Mohammad Reza, Somayeh Avarand, and Maryam Jamali. "An Anthropological study of Melmedas in Iran and Siren in Greece." The Anthropologist 18.3 (2014): 981-989.

- ^"Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^Hughes, Patrick; Hughes, Thomas Patrick (1995).Dictionary of Islam.Asian Educational Services.ISBN9788120606722.

- ^Marzolph, Ulrich, and Richard van Leeuwen. "The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful: The Survival of Ancient Iranian Ethical Concepts in Persian Popular Narratives of the Islamic Period." The Idea of Iran: Tradition and Innovation in Early Islamic Persia (2012): 16-29.

- ^Marzolph, Ulrich, and Richard van Leeuwen. "The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful: The Survival of Ancient Iranian Ethical Concepts in Persian Popular Narratives of the Islamic Period." The Idea of Iran: Tradition and Innovation in Early Islamic Persia (2012): 16-29.

- ^Frederick M. SmithThe Self Possessed: Deity and Spirit Possession in South Asian Literature and CivilizationColumbia University Press 2012ISBN978-0-231-51065-3page 570

- ^Yves BonnefoyAsian MythologiesUniversity of Chicago Press 1993ISBN978-0-226-06456-7p. 322

- ^Claus, Peter, Sarah Diamond, and Margaret Mills. South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, 2020. p. 463

- ^DAVLETSHİNA, Leyla, and Enzhe SADYKOVA. "ÇAĞDAŞ TATAR HALK BİLİMİNDEKİ KÖTÜ RUHLAR ÜZERİNE BİR ÇALIŞMA: PERİ BAŞKA, CİN BAŞKA." Uluslararası Türk Lehçe Araştırmaları Dergisi (TÜRKLAD) 4.2 (2020): 366-374.

- ^DAVLETSHİNA, Leyla, and Enzhe SADYKOVA. "ÇAĞDAŞ TATAR HALK BİLİMİNDEKİ KÖTÜ RUHLAR ÜZERİNE BİR ÇALIŞMA: PERİ BAŞKA, CİN BAŞKA." Uluslararası Türk Lehçe Araştırmaları Dergisi (TÜRKLAD) 4.2 (2020): 366-374.

- ^MacDonald, D.B., Massé, H., Boratav, P.N., Nizami, K.A. and Voorhoeve, P., “Ḏj̲inn”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 31 January 2024 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0191> First published online: 2012 First print edition:ISBN978-90-04-16121-4,1960-2007

- ^Shamanism and Islam: Sufism, Healing Rituals and Spirits in the Muslim World. (2017). Vereinigtes Königreich: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 148

- ^Kúnos, Ignác (1888)."Osmanische Volksmärchen I. (Schluss)".Ungarische Revue(in German).8:337.

- ^Boratav, P.N. and J.T.P. de Bruijn, “Parī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 31 January 2024doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0886.First published online: 2012. First print edition:ISBN978-90-04-16121-4,1960-2007

- ^Basilov, Vladimir N. "Shamanism in central Asia." The Realm of Extra-human. Agents and Audiences (1976): 149-157.

- ^ZARCONE, EDITED BY THIERRY, and ANGELA HOBART. "AND ISLAM." The Sufi orders in northern Central Asia.

- ^Ferrari, Fabrizio M. (2011).Health and religious rituals in South Asia: disease, possession, and healing.London: Routledge.ISBN978-0-203-83386-5.OCLC739388185.p. 35-38

- ^Peter J. Claus, Sarah Diamond, Margaret Ann MillsSouth Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri LankaTaylor & Francis, 2003ISBN978-0-415-93919-5page 463

- ^Olinthus Gilbert GregoryPantologia. A new (cabinet) cyclopædia, by J.M. Good, O. Gregory, and N. Bosworth assisted by other gentlemen of eminence, Band 8Oxford University 1819 digitalized 2006 sec. 17

- ^Nelson, Thomas (1922).Nelson's New Dictionary of the English Language.Thomas Nelson & Sons. p. 234.

- ^Abedinifard, Mostafa; Azadibougar, Omid; Vafa, Amirhossein, eds. (2021). Persian Literature as World Literature. Literatures as World Literature. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 37–43.ISBN978-1-5013-5420-5

- ^Abedinifard, Mostafa; Azadibougar, Omid; Vafa, Amirhossein, eds. (2021). Persian Literature as World Literature. Literatures as World Literature. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 37–43.ISBN978-1-5013-5420-5

- ^Abedinifard, Mostafa; Azadibougar, Omid; Vafa, Amirhossein, eds. (2021). Persian Literature as World Literature. Literatures as World Literature. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 37–43.ISBN978-1-5013-5420-5

- ^Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, and Mehdi Aminrazavi, eds. An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, Vol. 2: From Zoroaster to Omar Khayyam. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2007. pp. 320-323

- ^Marzolph, Ulrich, and Richard van Leeuwen. "The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful: The Survival of Ancient Iranian Ethical Concepts in Persian Popular Narratives of the Islamic Period." The Idea of Iran: Tradition and Innovation in Early Islamic Persia (2012): 16-29.

- Ferdowsi; Zimmern, Helen (trans.) (1883)."The Epic of Kings".Internet Sacred Text Archive.RetrievedOctober 18,2011.