Plant nutrients in soil

Seventeenelementsornutrientsare essential for plant growth and reproduction. They arecarbon(C),hydrogen(H),oxygen(O),nitrogen(N),phosphorus(P),potassium(K),sulfur(S),calcium(Ca),magnesium(Mg),iron(Fe),boron(B),manganese(Mn),copper(Cu),zinc(Zn),molybdenum(Mo),nickel(Ni) andchlorine(Cl).[1][2][3]Nutrients required for plants to complete their life cycle are consideredessential nutrients.Nutrients that enhance the growth of plants but are not necessary to complete the plant's life cycle are considered non-essential, although some of them, such assilicon(Si), have been shown to improve nutrent availability,[4]hence the use ofstinging nettleandhorsetail(both silica-rich)macerationsinBiodynamic agriculture.[5]With the exception of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, which are supplied by carbon dioxide and water, and nitrogen, provided throughnitrogen fixation,[3]the nutrients derive originally from the mineral component of the soil. TheLaw of the Minimumexpresses that when the available form of a nutrient is not in enough proportion in the soil solution, then other nutrients cannot be taken up at an optimum rate by a plant.[6]A particular nutrient ratio of the soil solution is thus mandatory for optimizing plant growth, a value which might differ from nutrient ratios calculated from plant composition.[7]

Plant uptake of nutrients can only proceed when they are present in a plant-available form. In most situations, nutrients are absorbed in an ionic form bydiffusionorabsorptionof the soil water. Although minerals are the origin of most nutrients, and the bulk of most nutrient elements in the soil is held in crystalline form within primary and secondary minerals, theyweathertoo slowly to support rapid plant growth. For example, the application of finely ground minerals,feldsparandapatite,to soil seldom provides the necessary amounts of potassium and phosphorus at a rate sufficient for good plant growth, as most of the nutrients remain bound in the crystals of those minerals.[8]

The nutrients adsorbed onto the surfaces ofclaycolloidsandsoil organic matterprovide a more accessible reservoir of many plant nutrients (e.g. K, Ca, Mg, P, Zn). As plants absorb the nutrients from the soil water, the soluble pool is replenished from the surface-bound pool. The decomposition ofsoil organic matterby microorganisms is another mechanism whereby the soluble pool of nutrients is replenished – this is important for the supply of plant-available N, S, P, and B from soil.[9]

Gram for gram, the capacity ofhumusto hold nutrients and water is far greater than that of clay minerals, most of the soilcation exchange capacityarising from chargedcarboxylicgroups on organic matter.[10]However, despite the great capacity of humus to retain water once water-soaked, its highhydrophobicitydecreases itswettability.[11]All in all, small amounts of humus may remarkably increase the soil's capacity to promote plant growth.[12][9]

| Element | Symbol | Ion or molecule |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon | C | CO2(mostly through leaf and root litter) |

| Hydrogen | H | H+,HOH (water) |

| Oxygen | O | O2−,OH−,CO32−,SO42−,CO2 |

| Phosphorus | P | H2PO4−,HPO42−(phosphates) |

| Potassium | K | K+ |

| Nitrogen | N | NH4+,NO3−(ammonium, nitrate) |

| Sulfur | S | SO42− |

| Calcium | Ca | Ca2+ |

| Iron | Fe | Fe2+,Fe3+(ferrous, ferric) |

| Magnesium | Mg | Mg2+ |

| Boron | B | H3BO3,H2BO3−,B(OH)4− |

| Manganese | Mn | Mn2+ |

| Copper | Cu | Cu2+ |

| Zinc | Zn | Zn2+ |

| Molybdenum | Mo | MoO42−(molybdate) |

| Chlorine | Cl | Cl−(chloride) |

Uptake processes[edit]

Nutrients in the soil are taken up by the plant through its roots, and in particular itsroot hairs.To be taken up by a plant, a nutrient element must be located near the root surface; however, the supply of nutrients in contact with the root is rapidly depleted within a distance of ca. 2 mm.[14]There are three basic mechanisms whereby nutrient ions dissolved in the soil solution are brought into contact with plant roots:

All three mechanisms operate simultaneously, but one mechanism or another may be most important for a particular nutrient.[15]For example, in the case ofcalcium,which is generally plentiful in the soil solution, except whenaluminiumover competes calcium oncation exchangesites in very acid soils (pH less than 4),[16]mass flow alone can usually bring sufficient amounts to the root surface. However, in the case ofphosphorus,diffusion is needed to supplement mass flow.[17]For the most part, nutrient ions must travel some distance in the soil solution to reach the root surface. This movement can take place by mass flow, as when dissolved nutrients are carried along with the soil water flowing toward a root that is actively drawing water from the soil. In this type of movement, the nutrient ions are somewhat analogous to leaves floating down a stream. In addition, nutrient ions continually move by diffusion from areas of greater concentration toward the nutrient-depleted areas of lower concentration around the root surface. That process is due to random motion, also calledBrownian motion,of molecules within a gradient of decreasing concentration.[18]By this means, plants can continue to take up nutrients even at night, when water is only slowly absorbed into the roots astranspirationhas almost stopped followingstomatalclosure. Finally, root interception comes into play as roots continually grow into new, undepleted soil. By this way roots are also able to absorbnanomaterialssuch asnanoparticulateorganic matter.[19]

| Nutrient | Approximate percentage supplied by: | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass flow | Root interception | Diffusion | |

| Nitrogen | 98.8 | 1.2 | 0 |

| Phosphorus | 6.3 | 2.8 | 90.9 |

| Potassium | 20.0 | 2.3 | 77.7 |

| Calcium | 71.4 | 28.6 | 0 |

| Sulfur | 95.0 | 5.0 | 0 |

| Molybdenum | 95.2 | 4.8 | 0 |

In the above table, phosphorus and potassium nutrients move more by diffusion than they do by mass flow in the soil water solution, as they are rapidly taken up by the roots creating a concentration of almost zero near the roots (the plants cannot transpire enough water to draw more of those nutrients near the roots). The very steep concentration gradient is of greater influence in the movement of those ions than is the movement of those by mass flow.[21]The movement by mass flow requires the transpiration of water from the plant causing water and solution ions to also move toward the roots.[22]Movement by root interception is slowest, being at the rate plants extend their roots.[23]

Plants move ions out of their roots in an effort to move nutrients in from the soil, an exchange process which occurs in the rootapoplast.[24]Hydrogen H+is exchanged for other cations, and carbonate (HCO3−) and hydroxide (OH−) anions are exchanged for nutrient anions.[25]As plant roots remove nutrients from the soil water solution, they are replenished as other ions move off of clay and humus (byion exchangeordesorption), are added from theweatheringof soil minerals, and are released by thedecomposition of soil organic matter.However, the rate at which plant roots remove nutrients may not cope with the rate at which they are replenished in the soil solution, stemming in nutrient limitation to plant growth.[26]Plants derive a large proportion of their anion nutrients from decomposing organic matter, which typically holds about 95 percent of the soil nitrogen, 5 to 60 percent of the soil phosphorus and about 80 percent of the soil sulfur. Where crops are produced, the replenishment of nutrients in the soil must usually be augmented by the addition of fertilizer or organic matter.[20]

Because nutrient uptake is an active metabolic process, conditions that inhibit root metabolism may also inhibit nutrient uptake.[27]Examples of such conditions includewaterloggingorsoil compactionresulting in poorsoil aeration,excessively high or low soil temperatures, and above-ground conditions that result in low translocation of sugars to plant roots.[28]

Carbon[edit]

Plants obtain their carbon from atmosphericcarbon dioxidethroughphotosyntheticcarboxylation,to which must be added the uptake of dissolved carbon from the soil solution[29]and carbon transfer throughmycorrhizal networks.[30]About 45% of a plant's dry mass is carbon; plant residues typically have a carbon to nitrogen ratio (C/N) of between 13:1 and 100:1. As the soil organic material is digested bymicro-organismsandsaprophagoussoil fauna,the C/N decreases as the carbonaceous material is metabolized and carbon dioxide (CO2) is released as a byproduct which then finds its way out of the soil and into the atmosphere. Nitrogen turnover (mostly involved inprotein turnover) is lesser than that of carbon (mostly involved inrespiration) in the living, then dead matter ofdecomposers,which are always richer in nitrogen thanplant litter,and so it builds up in the soil.[31]Normal CO2concentration in the atmosphere is 0.03%, this can be the factor limiting plant growth. In a field of maize on a still day during high light conditions in the growing season, the CO2concentration drops very low, but under such conditions the crop could use up to 20 times the normal concentration. The respiration of CO2by soil micro-organisms decomposing soil organic matter and the CO2respired by roots contribute an important amount of CO2to thephotosynthesisingplants, to which must be added the CO2respired by aboveground plant tissues.[32]Root-respired CO2can be accumulated overnight within hollow stems of plants, to be further used for photosynthesis during the day.[33]Within the soil, CO2concentration is 10 to 100 times that of atmospheric levels but may rise to toxic levels if the soil porosity is low or if diffusion is impeded by flooding.[34][1][35]

Nitrogen[edit]

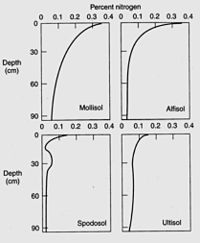

Nitrogen is the most critical element obtained by plants from the soil, to the exception of moist tropical forests where phosphorus is thelimiting soil nutrient,[36]andnitrogen deficiencyoften limits plant growth.[37]Plants can use nitrogen as either theammoniumcation (NH4+) or the anionnitrate(NO3−). Plants are commonly classified as ammonium or nitrate plants according to their preferential nitrogen nutrition.[38]Usually, most of the nitrogen in soil is bound within organic compounds that make up thesoil organic matter,and must bemineralizedto the ammonium or nitrate form before it can be taken up by most plants. However, symbiosis withmycorrhizal fungiallow plants to get access to the organic nitrogen pool where and when mineral forms of nitrogen are poorly available.[39]The total nitrogen content depends largely on the soil organic matter content, which in turn depends ontexture,climate,vegetation,topography,age andsoil management.[40]Soil nitrogen typically decreases by 0.2 to 0.3% for every temperature increase by 10 °C. Usually, grassland soils contain more soil nitrogen than forest soils, because of a higher turnover rate of grassland organic matter.[41]Cultivation decreases soil nitrogen by exposing soil organic matter to decomposition by microorganisms,[42]most losses being caused bydenitrification,[43]and soils under no-tillage maintain more soil nitrogen than tilled soils.[44]

Somemicro-organismsare able to metabolise organic matter and release ammonium in a process calledmineralisation.Others, callednitrifiers,take freeammoniumornitriteas an intermediary step in the process ofnitrification,and oxidise it tonitrate.Nitrogen-fixing bacteriaare capable of metabolising N2into the form ofammoniaor related nitrogenous compounds in a process callednitrogen fixation.Both ammonium and nitrate can beimmobilizedby their incorporation into microbial living cells, where it is temporarily sequestered in the form ofamino acidsandproteins.Nitrate may be lost from the soil to the atmosphere when bacteria metabolise it to the gases NH3,N2and N2O, a process calleddenitrification.Nitrogen may also beleachedfrom thevadose zoneif in the form of nitrate, acting as apollutantif it reaches thewater tableorflows over land,more especially in agricultural soils under high use of nutrient fertilizers.[45]Ammonium may also be sequestered in 2:1clay minerals.[46]A small amount of nitrogen is added to soil byrainfall,to the exception of wide areas of North America and West Europe where the excess use ofnitrogen fertilizersandmanurehas causedatmospheric pollutionby ammonia emission, stemming insoil acidificationandeutrophicationof soils andaquatic ecosystems.[47][48][9][49][50][51]

Gains[edit]

In the process ofmineralisation,microbes feed on organic matter, releasing ammonia (NH3), ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3−) and other nutrients. As long as the carbon to nitrogen ratio (C/N) of fresh residues in the soil is above 30:1, nitrogen will be in short supply for the nitrogen-rich microbal biomass (nitrogen deficiency), and other bacteria will uptake ammonium and to a lesser extent nitrate and incorporate them into their cells in theimmobilizationprocess.[52]In that form the nitrogen is said to beimmobilised.Later, when such bacteria die, they too aremineralisedand some of the nitrogen is released as ammonium and nitrate. Predation of bacteria by soil fauna, in particularprotozoaandnematodes,play a decisive role in the return of immobilized nitrogen to mineral forms.[53]If the C/N of fresh residues is less than 15, mineral nitrogen is freed to the soil and directly available to plants.[54]Bacteria may on average add 25 pounds (11 kg) nitrogen per acre, and in an unfertilised field, this is the most important source of usable nitrogen. In a soil with 5% organic matter perhaps 2 to 5% of that is released to the soil by such decomposition. It occurs fastest in warm, moist, well aerated soil.[55]The mineralisation of 3% of the organic material of a soil that is 4% organic matter overall, would release 120 pounds (54 kg) of nitrogen as ammonium per acre.[56]

| Organic Material | C:N Ratio |

|---|---|

| Alfalfa | 13 |

| Bacteria | 4 |

| Clover, green sweet | 16 |

| Clover, mature sweet | 23 |

| Fungi | 9 |

| Forest litter | 30 |

| Humus in warm cultivated soils | 11 |

| Legume-grass hay | 25 |

| Legumes (alfalfa or clover), mature | 20 |

| Manure, cow | 18 |

| Manure, horse | 16–45 |

| Manure, human | 10 |

| Oat straw | 80 |

| Straw, cornstalks | 90 |

| Sawdust | 250 |

Innitrogen fixation,rhizobiumbacteria convert N2to ammonia (NH3), which is rapidly converted toamino acids,parts of which are used by the rhizobia for the synthesis of their own biomass proteins, while other parts are transported to thexylemof the host plant.[58]Rhizobiashare asymbiotic relationshipwith host plants, since rhizobia supply the host with nitrogen and the host provides rhizobia with other nutrients and a safe environment. It is estimated that such symbiotic bacteria in theroot nodulesoflegumesadd 45 to 250 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year, which may be sufficient for the crop. Other, free-living nitrogen-fixingdiazotrophbacteriaandarchaealive independently in the soil and release mineral forms of nitrogen when their dead bodies are converted by way ofmineralization.[59]

Some amount of atmospheric nitrogen is transformed bylightningsin gaseousnitric oxide(NO) andnitrogen dioxide(NO2−).[60]Nitrogen dioxide is soluble in water to formnitric acid(HNO3) dissociating in H+and NO3−.Ammonia, NH3,previously emitted from the soil, may fall with precipitation as nitric acid at a rate of about five pounds nitrogen per acre per year.[61]

Sequestration[edit]

When bacteria feed on soluble forms of nitrogen (ammonium and nitrate), they temporarily sequester that nitrogen in their bodies in a process calledimmobilization.At a later time when those bacteria die, their nitrogen may be released as ammonium by the process of mineralization, sped up by predatory fauna.[62]

Protein material is easily broken down, but the rate of its decomposition is slowed by its attachment to the crystalline structure of clay and when trapped between the clay layers[63]or attached to rough clay surfaces.[64]The layers are small enough that bacteria cannot enter.[65]Some organisms exude extracellular enzymes that can act on the sequestered proteins. However, those enzymes too may be trapped on the clay crystals, resulting in a complex interaction between proteins, microbial enzymes and mineral surfaces.[66]

Ammonium fixation occurs mainly between the layers of 2:1 type clay minerals such asillite,vermiculiteormontmorillonite,together with ions of similarionic radiusand lowhydration energysuch aspotassium,but a small proportion of ammonium is also fixed in thesiltfraction.[67]Only a small fraction of soil nitrogen is held this way.[68]

Losses[edit]

Usable nitrogen may be lost from soils when it is in the form ofnitrate,as it is easilyleached,contrary toammoniumwhich is easily fixed.[69]Further losses of nitrogen occur bydenitrification,the process whereby soil bacteria convert nitrate (NO3−) to nitrogen gas, N2or N2O. This occurs when poorsoil aerationlimits free oxygen, forcing bacteria to use the oxygen in nitrate for their respiratory process. Denitrification increases when oxidisable organic material is available, as inorganic farming[69]and when soils are warm and slightly acidic, as currently happens in tropical areas.[70]Denitrification may vary throughout a soil as the aeration varies from place to place.[71]Denitrification may cause the loss of 10 to 20 percent of the available nitrates within a day and when conditions are favourable to that process, losses of up to 60 percent of nitrate applied as fertiliser may occur.[72]

Ammonia volatilisationoccurs when ammonium reacts chemically with analkaline soil,converting NH4+to NH3.[73]The application of ammonium fertiliser to such a field can result in volatilisation losses of as much as 30 percent.[74]

All kinds of nitrogen losses, whether by leaching or volatilization, are responsible for a large part ofaquiferpollution[75]andair pollution,with concomitant effects onsoil acidificationandeutrophication,[76]a novel combination of environmental threats (acidity and excess nitrogen) to which extant organisms are badly adapted, causing severe biodiversity losses in natural ecosystems.[77]

Phosphorus[edit]

After nitrogen, phosphorus is probably the element most likely to be deficient in soils, although it often turns to be the most deficient in tropical soils where the mineral pool is depleted under intenseleachingandmineral weatheringwhile, contrary to nitrogen, phosphorus reserves cannot be replenished from other sources.[78]The soil mineralapatiteis the most common mineral source of phosphorus, from which it can be extracted by microbial and root exudates,[79][80]with an important contribution ofarbuscular mycorrhizalfungi.[81]The most common form of organic phosphate isphytate,the principal storage form of phosphorus in many plant tissues. While there is on average 1000 lb per acre (1120 kg per hectare) of phosphorus in the soil, it is generally in the form oforthophosphatewith low solubility, except when linked to ammonium or calcium, hence the use ofdiammonium phosphateormonocalcium phosphateas fertilizers.[82]Total phosphorus is about 0.1 percent by weight of the soil, but only one percent of that is directly available to plants. Of the part available, more than half comes from the mineralisation of organic matter. Agricultural fields may need to be fertilised to make up for the phosphorus that has been removed in the crop.[83]

When phosphorus does form solubilised ions of H2PO4−,if not taken up by plant roots these ions rapidly form insolublecalcium phosphatesor hydrous oxides of iron and aluminum. Phosphorus is largely immobile in the soil and is not leached but actually builds up in the surface layer if not cropped. The application of soluble fertilisers to soils may result inzincdeficiencies aszinc phosphatesform, but soil pH levels, partly depending on the form of phosphorus in the fertiliser, strongly interact with this effect, in some cases resulting in increased zinc availability.[84]Lack of phosphorus may interfere with the normal opening of the plant leafstomata,decreasedstomatal conductanceresulting in decreasedphotosynthesisand respiration rates[85]while decreasedtranspirationincreases plant temperature.[86]Phosphorus is most available when soil pH is 6.5 in mineral soils and 5.5 in organic soils.[74]

Potassium[edit]

The amount of potassium in a soil may be as much as 80,000 lb per acre-foot, of which only 150 lb is available for plant growth. Common mineral sources of potassium are the micabiotiteandpotassium feldspar,KAlSi3O8.Rhizospherebacteria, also calledrhizobacteria,contribute through the production oforganic acidsto its solubilization.[87]When solubilised, half will be held as exchangeable cations on clay while the other half is in the soil water solution. Potassium fixation often occurs when soils dry and the potassium is bonded between layers of 2:1expansive clayminerals such asillite,vermiculiteormontmorillonite.[88]Under certain conditions, dependent on the soil texture, intensity of drying, and initial amount of exchangeable potassium, the fixed percentage may be as much as 90 percent within ten minutes. Potassium may be leached from soils low in clay.[89][90]

Calcium[edit]

Calcium is one percent by weight of soils and is generally available but may be low as it is soluble and can be leached. It is thus low in sandy and heavily leached soil or strongly acidic mineral soils, resulting in excessive concentration of free hydrogen ions in the soil solution, and therefore these soils require liming.[91]Calcium is supplied to the plant in the form of exchangeable ions and moderately soluble minerals. There are four forms of calcium in the soil. Soil calcium can be in insoluble forms such ascalciteordolomite,in the soil solution in the form of adivalentcationor retained inexchangeable format the surface of mineral particles. Another form is when calcium complexes with organic matter, formingcovalent bondsbetweenorganic compoundswhich contribute tostructural stability.[92]Calcium is more available on the soil colloids than is potassium because the common mineralcalcite,CaCO3,is more soluble than potassium-bearing minerals such asfeldspar.[93]

Calcium uptake by roots is essential forplant nutrition,contrary to an old tenet that it wasluxury consumption.[94]Calcium is considered as an essential component of plantcell membranes,acounterionfor inorganic and organicanionsin thevacuole,and an intracellular messenger in thecytosol,playing a role in cellularlearningandmemory.[95]

Magnesium[edit]

Magnesiumis one of the dominant exchangeable cations in most soils (after calcium and potassium).Magnesiumis an essential element for plants, microbes and animals, being involved in manycatalytic reactionsand in the synthesis ofchlorophyll.Primary minerals that weather to release magnesium includehornblende,biotiteandvermiculite.Soil magnesium concentrations are generally sufficient for optimal plant growth, but highly weathered and sandy soils may be magnesium deficient due to leaching by heavy precipitation.[9][96]

Sulfur[edit]

Most sulfur is made available to plants, like phosphorus, by its release from decomposing organic matter.[96]Deficiencies may exist in some soils (especially sandy soils) and if cropped, sulfur needs to be added. The application of large quantities of nitrogen to fields that have marginal amounts of sulfur may cause sulfur deficiency by adilution effectwhen stimulation of plant growth by nitrogen increases the plant demand for sulfur.[97]A 15-ton crop of onions uses up to 19 lb of sulfur and 4 tons of alfalfa uses 15 lb per acre. Sulfur abundance varies with depth. In a sample of soils in Ohio, United States, the sulfur abundance varied with depths, 0–6 inches, 6–12 inches, 12–18 inches, 18–24 inches in the amounts: 1056, 830, 686, 528 lb per acre respectively.[98]

Micronutrients[edit]

Themicronutrientsessential in plant life, in their order of importance, includeiron,[99]manganese,[100]zinc,[101]copper,[102]boron,[103]chlorine[104]andmolybdenum.[105]The term refers to plants' needs, not to their abundance in soil. They are required in very small amounts but are essential toplant healthin that most are required parts ofenzymesystems which are involved in plantmetabolism.[106]They are generally available in the mineral component of the soil, but the heavy application of phosphates can cause a deficiency in zinc and iron by the formation of insoluble zinc and iron phosphates.[107]Iron deficiency, stemming in plantchlorosisandrhizosphereacidification, may also result from excessive amounts of heavy metals or calcium minerals (lime) in the soil.[108][109]Excess amounts of soluble boron, molybdenum and chloride are toxic.[110][111]

Non-essential nutrients[edit]

Nutrients which enhance the health but whose deficiency does not stop the life cycle of plants include:cobalt,strontium,vanadium,siliconandnickel.[112]As their importance is evaluated they may be added to the list of essential plant nutrients, as is the case for silicon.[113]

See also[edit]

- Alkali soil

- Sodic soils

- Cation-exchange capacity

- Soil contamination

- Soil fertility

- Index of soil-related articles

References[edit]

- ^abDean 1957,p. 80.

- ^Russel 1957,pp. 123–25.

- ^abWeil, Ray R.; Brady, Nyle C. (2017).The nature and properties of soils(15th ed.). Columbus, Ohio: Pearson.ISBN978-0133254488.Retrieved24 September2023.

- ^Pavlovic, Jelena; Kostic, Ljiljana; Bosnic, Predrag; Kirkby, Ernest A.; Nikolic, Miroslav (2021)."Interactions of silicon with essential and beneficial elements in plants".Frontiers in Plant Science.12(697592): 1–19.doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.697592.PMID34249069.

- ^Pairault, Liliana-Adriana; Tritean, Naomi; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, Diana; Oancea, Florin (2022)."Plant biostimulants based on nanoformulated biosilica recovered from silica-rich biomass"(PDF).Scientific Bulletin, Series F, Biotechnologies.26(1): 49–58.Retrieved1 October2023.

- ^Van der Ploeg, Rienk R.; Böhm, Wolfgang; Kirkham, Mary Beth (1999)."On the origin of the theory of mineral nutrition of plants and the Law of the Minimum".Soil Science Society of America Journal.63(5): 1055–62.Bibcode:1999SSASJ..63.1055V.CiteSeerX10.1.1.475.7392.doi:10.2136/sssaj1999.6351055x.

- ^Knecht, Magnus F.; Göransson, Anders (2004)."Terrestrial plants require nutrients in similar proportions".Tree Physiology.24(4): 447–60.doi:10.1093/treephys/24.4.447.PMID14757584.

- ^Dean 1957,pp. 80–81.

- ^abcdRoy, R. N.; Finck, Arnold; Blair, Graeme J.; Tandon, Hari Lal Singh (2006)."Chapter 4: Soil fertility and crop production"(PDF).Plant nutrition for food security: a guide for integrated nutrient management.Rome, Italy:Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.pp. 43–90.ISBN978-92-5-105490-1.Retrieved8 October2023.

- ^Parfitt, Roger L.; Giltrap, Donna J.; Whitton, Joe S. (1995)."Contribution of organic matter and clay minerals to the cation exchange capacity of soil".Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis.26(9–10): 1343–55.Bibcode:1995CSSPA..26.1343P.doi:10.1080/00103629509369376.Retrieved8 October2023.

- ^Hajnos, Mieczyslaw; Jozefaciuk, Grzegorz; Sokołowska, Zofia; Greiffenhagen, Andreas; Wessolek, Gerd (2003)."Water storage, surface, and structural properties of sandy forest humus horizons".Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science.166(5): 625–34.Bibcode:2003JPNSS.166..625H.doi:10.1002/jpln.200321161.Retrieved8 October2023.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,pp. 123–31.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,p. 125.

- ^Föhse, Doris; Claassen, Norbert; Jungk, Albrecht (1991)."Phosphorus efficiency of plants. II. Significance of root radius, root hairs and cation-anion balance for phosphorus influx in seven plant species"(PDF).Plant and Soil.132(2): 261–72.doi:10.1007/BF00010407.S2CID28489187.Retrieved8 October2023.

- ^Barber, Stanley A. (1966)."The role of root interception, mass flow and diffusion in regulating the uptake of ions by plants from soil"(PDF).Limiting steps in ion uptake by plants from soil.Vienna, Austria:International Atomic Energy Agency.pp. 39–45.Retrieved15 October2023.

- ^Lawrence, Gregory B.; David, Mark B.; Shortle, Walter C. (1995)."A new mechanism for calcium loss in forest floor soils".Nature.378(6553): 162–65.Bibcode:1995Natur.378..162L.doi:10.1038/378162a0.S2CID4365594.Retrieved15 October2023.

- ^Olsen, S. R. (1965)."Phosphorus diffusion to plant roots"(PDF).Plant nutrient supply and movement.Vienna, Austria:International Atomic Energy Agency.pp. 130–42.Retrieved15 October2023.

- ^Brinkman, H. C. (1940)."Brownian motion in a field of force and the diffusion theory of chemical reactions. II"(PDF).Physica.22(1–5): 149–55.doi:10.1016/S0031-8914(56)80019-0.Retrieved15 October2023.

- ^Lin, Sijie; Reppert, Jason; Hu, Qian; Hudson, Joan S.; Reid, Michelle L.; Ratnikova, Tatsiana A.; Rao, Apparao M.; Luo, Hong; Ke, Pu Chun (2009)."Uptake, translocation, and transmission of carbon nanomaterials in rice plants".Small.5(10): 1128–32.doi:10.1002/smll.200801556.PMID19235197.Retrieved15 October2023.

- ^abDonahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,p. 126.

- ^"Plant nutrition".Northern Arizona University.Archived fromthe originalon 14 May 2013.

- ^Matimati, Ignatious; Verboom, G. Anthony; Cramer, Michael D. (2014)."Nitrogen regulation of transpiration controls mass-flow acquisition of nutrients".Journal of Experimental Botany.65(1): 159–68.doi:10.1093/jxb/ert367.PMC3883293.PMID24231035.

- ^Mengel, Dave."Roots, growth and nutrient uptake"(PDF).Purdue University,Agronomy Department.Retrieved22 October2023.

- ^Sattelmacher, Burkhard (2001)."The apoplast and its significance for plant mineral nutrition".New Phytologist.149(2): 167–92.doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00034.x.PMID33874640.

- ^Hinsinger, Philippe; Plassard, Claude; Tang, Caixian; Jaillard, Benoît (2003)."Origins of root-mediated pH changes in the rhizosphere and their responses to environmental constraints: a review".Plant and Soil.248(1): 43–59.Bibcode:2003PlSoi.248...43H.doi:10.1023/A:1022371130939.S2CID23929321.Retrieved29 October2023.

- ^Chapin, F. Stuart III; Vitousek, Peter M.; Van Cleve, Keith (1986)."The nature of nutrient limitation in plant communities".American Naturalist.127(1): 48–58.doi:10.1086/284466.JSTOR2461646.S2CID84381961.Retrieved29 October2023.

- ^Alam, Syed Manzoor (1999)."Nutrient uptake by plants under stress conditions".In Pessarakli, Mohammad (ed.).Handbook of plant and crop stress(2nd ed.). New York, New York:Marcel Dekker.pp. 285–313.ISBN978-0824719487.Retrieved29 October2023.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,pp. 123–28.

- ^Rasmussen, Jim;Kuzyakov, Yakov(2009)."Carbon isotopes as proof for plant uptake of organic nitrogen: relevance of inorganic carbon uptake".Soil Biology and Biochemistry.41(7): 1586–87.doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.03.006.Retrieved5 November2023.

- ^Fitter, Alastair H.; Graves, Jonathan D.; Watkins, N. K.; Robinson, David; Scrimgeour, Charlie (1998)."Carbon transfer between plants and its control in networks of arbuscular mycorrhizas".Functional Ecology.12(3): 406–12.Bibcode:1998FuEco..12..406F.doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00206.x.

- ^Manzoni, Stefano; Trofymow, John A.; Jackson, Robert B.; Porporato, Amilcare (2010)."Stoichiometric controls on carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus dynamics in decomposing litter"(PDF).Ecological Monographs.80(1): 89–106.Bibcode:2010EcoM...80...89M.doi:10.1890/09-0179.1.Retrieved5 November2023.

- ^Teskey, Robert O.; Saveyn, An; Steppe, Kathy; McGuire, Mary Ann (2007)."Origin, fate and significance of CO2 in tree stems".New Phytologist.177(1): 17–32.doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02286.x.PMID18028298.

- ^Billings, William Dwight; Godfrey, Paul Joseph (1967)."Photosynthetic utilization of internal carbon dioxide by hollow-stemmed plants".Science.158(3797): 121–23.Bibcode:1967Sci...158..121B.doi:10.1126/science.158.3797.121.JSTOR1722393.PMID6054809.S2CID13237417.Retrieved5 November2023.

- ^Wadleigh 1957,p. 41.

- ^Broadbent 1957,p. 153.

- ^Vitousek, Peter M. (1984)."Litterfall, nutrient cycling, and nutrient limitation in tropical forests".Ecology.65(1): 285–98.Bibcode:1984Ecol...65..285V.doi:10.2307/1939481.JSTOR1939481.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,p. 128.

- ^Forde, Bryan G.; Clarkson, David T. (1999)."Nitrate and ammonium nutrition of plants: physiological and molecular perspectives".Advances in Botanical Research.30(C): 1–90.doi:10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60226-8.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Hodge, Angela; Campbell, Colin D.; Fitter, Alastair H. (2001)."An arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus accelerates decomposition and acquires nitrogen directly from organic material"(PDF).Nature.413(6853): 297–99.Bibcode:2001Natur.413..297H.doi:10.1038/35095041.PMID11565029.S2CID4423745.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Burke, Ingrid C.;Yonker, Caroline M.; Parton, William J.; Cole, C. Vernon; Flach, Klaus; Schimel, David S. (1989)."Texture, climate, and cultivation effects on soil organic matter content in U.S. grassland soils".Soil Science Society of America Journal.53(3): 800–05.Bibcode:1989SSASJ..53..800B.doi:10.2136/sssaj1989.03615995005300030029x.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Enríquez, Susana; Duarte, Carlos M.; Sand-Jensen, Kaj (1993)."Patterns in decomposition rates among photosynthetic organisms: the importance of detritus C:N:P content".Oecologia.94(4): 457–71.Bibcode:1993Oecol..94..457E.doi:10.1007/BF00566960.PMID28313985.S2CID22732277.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Tiessen, Holm; Stewart, John W. B.; Bettany, Jeff R. (1982)."Cultivation effects on the amounts and concentration of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in grassland soils"(PDF).Agronomy Journal.74(5): 831–35.Bibcode:1982AgrJ...74..831T.doi:10.2134/agronj1982.00021962007400050015x.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Philippot, Laurent; Hallin, Sara; Schloter, Michael (2007)."Ecology of denitrifying prokaryotes in agricultural soil".In Sparks, Donald L. (ed.).Advances in Agronomy, Volume 96.Amsterdam, the Netherlands:Elsevier.pp. 249–305.CiteSeerX10.1.1.663.4557.ISBN978-0-12-374206-3.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Doran, John W. (1987)."Microbial biomass and mineralizable nitrogen distributions in no-tillage and plowed soils".Biology and Fertility of Soils.5(1): 68–75.doi:10.1007/BF00264349.S2CID44201431.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Mahvi, Amir H.; Nouri, Jafar; Babaei, Ali A.; Nabizadeh, Ramin (2005)."Agricultural activities impact on groundwater nitrate pollution".International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology.2(1): 41–47.Bibcode:2005JEST....2...41M.doi:10.1007/BF03325856.hdl:1807/9114.S2CID94640003.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Scherer, Heinrich W.; Feils, E.; Beuters, Patrick (2014)."Ammonium fixation and release by clay minerals as influenced by potassium"(PDF).Plant, Soil and Environment.60(7): 325–31.doi:10.17221/202/2014-PSE.S2CID55200516.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Barak, Phillip; Jobe, Babou O.; Krueger, Armand R.; Peterson, Lloyd A.; Laird, David A. (1997)."Effects of long-term soil acidification due to nitrogen fertilizer inputs in Wisconsin".Plant and Soil.197(1): 61–69.doi:10.1023/A:1004297607070.S2CID2410167.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Van Egmond, Klaas; Bresser, Ton; Bouwman, Lex (2002)."The European nitrogen case"(PDF).Ambio.31(2): 72–78.Bibcode:2002Ambio..31...72V.doi:10.1579/0044-7447-31.2.72.PMID12078012.S2CID1114679.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Allison 1957,pp. 85–94.

- ^Broadbent 1957,pp. 152–55.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,pp. 128–31.

- ^Recous, Sylvie; Mary, Bruno (1990)."Microbial immobilization of ammonium and nitrate in cultivated soils".Soil Biology and Biochemistry.22(7): 913–22.doi:10.1016/0038-0717(90)90129-N.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Verhoef, Herman A.; Brussaard, Lijbert (1990)."Decomposition and nitrogen mineralization in natural and agro-ecosystems: the contribution of soil animals".Biogeochemistry.11(3): 175–211.Bibcode:1990Biogc..11..175V.doi:10.1007/BF00004496.S2CID96922131.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Chen, Baoqing; Liu, EnKe; Tian, Qizhuo; Yan, Changrong; Zhang, Yanqing (2014)."Soil nitrogen dynamics and crop residues: a review".Agronomy for Sustainable Development.34(2): 429–42.doi:10.1007/s13593-014-0207-8.S2CID18024074.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Griffin, Timothy S.; Honeycutt, Charles W.; He, Zhijun (2002)."Effects of temperature, soil water status, and soil type on swine slurry nitrogen transformations".Biology and Fertility of Soils.36(6): 442–46.Bibcode:2002BioFS..36..442T.doi:10.1007/s00374-002-0557-2.S2CID19377528.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,pp. 129–30.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,p. 145.

- ^Lodwig, Emma; Hosie, Arthur H. F.; Bourdès, Alexandre; Findlay, Kim; Allaway, David; Karunakaran, Ramakrishnan; Downie, J. Allan; Poole, Philip S. (2003)."Amino-acid cycling drives nitrogen fixation in the legume–Rhizobium symbiosis".Nature.422(6933): 722–26.Bibcode:2003Natur.422..722L.doi:10.1038/nature01527.PMID12700763.S2CID4429613.Retrieved12 November2023.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,pp. 128–29.

- ^Hill, Robert D.; Rinker, Robert G.; Wilson, H. Dale (1980)."Atmospheric nitrogen fixation by lightning".Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences.37(1): 179–92.Bibcode:1980JAtS...37..179H.doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1980)037<0179:ANFBL>2.0.CO;2.

- ^Allison 1957,p. 87.

- ^Ferris, Howard; Venette, Robert C.; Van der Meulen, Hans R.; Lau, Serrine S. (1998)."Nitrogen mineralization by bacterial-feeding nematodes: verification and measurement".Plant and Soil.203(2): 159–71.doi:10.1023/A:1004318318307.S2CID20632698.Retrieved19 November2023.

- ^Violante, Antonio; de Cristofaro, Annunziata; Rao, Maria A.; Gianfreda, Liliana (1995)."Physicochemical properties of protein-smectite and protein-Al(OH)x-smectite complexes".Clay Minerals.30(4): 325–36.Bibcode:1995ClMin..30..325V.doi:10.1180/claymin.1995.030.4.06.S2CID94630893.Retrieved19 November2023.

- ^Vogel, Cordula; Mueller, Carsten W.; Höschen, Carmen; Buegger, Franz; Heister, Katja; Schulz, Stefanie; Schloter, Michael; Kögel-Knabner, Ingrid (2014)."Submicron structures provide preferential spots for carbon and nitrogen sequestration in soils".Nature Communications.5(2947): 1–7.Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.2947V.doi:10.1038/ncomms3947.PMC3896754.PMID24399306.

- ^Ruamps, Léo Simon; Nunan, Naoise; Chenu, Claire (2011)."Microbial biogeography at the soil pore scale".Soil Biology and Biochemistry.43(2): 280–86.doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.10.010.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^Quiquampoix, Hervé; Burns, Richard G. (2007)."Interactions between proteins and soil mineral surfaces: environmental and health consequences".Elements.3(6): 401–06.Bibcode:2007Eleme...3..401Q.doi:10.2113/GSELEMENTS.3.6.401.Retrieved17 November2023.

- ^Nieder, Rolf; Benbi, Dinesh K.; Scherer, Heinrich W. (2011)."Fixation and defixation of ammonium in soils: a review".Biology and Fertility of Soils.47(1): 1–14.Bibcode:2011BioFS..47....1N.doi:10.1007/s00374-010-0506-4.S2CID7284269.

- ^Allison 1957,p. 90.

- ^abKramer, Sasha B.; Reganold, John P.; Glover, Jerry D.;Bohannan, Brendan J.M.;Mooney, Harold A. (2006)."Reduced nitrate leaching and enhanced denitrifier activity and efficiency in organically fertilized soils".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.103(12): 4522–27.Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.4522K.doi:10.1073/pnas.0600359103.PMC1450204.PMID16537377.

- ^Robertson, G. Philip (1989)."Nitrification and denitrification in humid tropical ecosystems: potential controls on nitrogen retention"(PDF).In Proctor, John (ed.).Mineral nutrients in tropical forest and savanna ecosystems.Cambridge, Massachusetts:Blackwell Scientific.ISBN978-0632025596.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Parkin, Timothy B.; Robinson, Joseph A. (1989)."Stochastic models of soil denitrification".Applied and Environmental Microbiology.55(1): 72–77.Bibcode:1989ApEnM..55...72P.doi:10.1128/AEM.55.1.72-77.1989.PMC184056.PMID16347838.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,p. 130.

- ^Rao, Desiraju L.N.; Batra, Lalit (1983)."Ammonia volatilization from applied nitrogen in alkali soils".Plant and Soil.70(2): 219–28.Bibcode:1983PlSoi..70..219R.doi:10.1007/BF02374782.S2CID24724207.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^abDonahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,p. 131.

- ^Lallouette, Vincent; Magnier, Julie; Petit, Katell; Michon, Janik (2014)."Agricultural practices and nitrates in aquatic environments"(PDF).The Brief.11(December): 1–16.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Choudhury, Abu T.M.A.; Kennedy, Ivan R. (2005)."Nitrogen fertilizer losses from rice soils and control of environmental pollution problems".Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis.36(11–12): 1625–39.Bibcode:2005CSSPA..36.1625C.doi:10.1081/css-200059104.S2CID44014545.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Roth, Tobias; Kohli, Lukas; Rihm, Beat; Achermann, Beat (2013)."Nitrogen deposition is negatively related to species richness and species composition of vascular plants and bryophytes in Swiss mountain grassland".Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment.178:121–26.Bibcode:2013AgEE..178..121R.doi:10.1016/j.agee.2013.07.002.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Vitousek, Peter M. (1984)."Litterfall, nutrient cycling, and nutrient limitation in tropical forests".Ecology.65(1): 285–98.Bibcode:1984Ecol...65..285V.doi:10.2307/1939481.JSTOR1939481.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Kucey, Reg M.N. (1983)."Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria and fungi in various cultivated and virgin Alberta soils".Canadian Journal of Soil Science.63(4): 671–78.doi:10.4141/cjss83-068.

- ^Khorassani, Reza; Hettwer, Ursula; Ratzinger, Astrid; Steingrobe, Bernd; Karlovsky, Petr; Claassen, Norbert (2011)."Citramalic acid and salicylic acid in sugar beet root exudates solubilize soil phosphorus".BMC Plant Biology.11(121): 1–8.doi:10.1186/1471-2229-11-121.PMC3176199.PMID21871058.

- ^Duponnois, Robin; Colombet, Aline; Hien, Victor; Thioulouse, Jean (2005)."The mycorrhizal fungusGlomus intraradicesand rock phosphate amendment influence plant growth and microbial activity in the rhizosphere of Acacia holosericea "(PDF).Soil Biology and Biochemistry.37(8): 1460–68.doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.09.016.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Syers, John Keith; Johnston, A. Edward; Curtin, Denis (2008).Efficiency of soil and fertilizer phosphorus use: reconciling changing concepts of soil phosphorus behaviour with agronomic information(PDF).Rome, Italy:Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.ISBN978-92-5-105929-6.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Olsen & Fried 1957,p. 96.

- ^Lambert, Raphaël; Grant, Cynthia; Sauvé, Sébastien (2007)."Cadmium and zinc in soil solution extracts following the application of phosphate fertilizers".Science of the Total Environment.378(3): 293–305.Bibcode:2007ScTEn.378..293L.doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.02.008.PMID17400282.Retrieved26 November2023.

- ^Terry, Norman; Ulrich, Albert (1973)."Effects of phosphorus deficiency on the photosynthesis and respiration of leaves of sugar beet".Plant Physiology.51(1): 43–47.doi:10.1104/pp.51.1.43.PMC367354.PMID16658294.

- ^Pallas, James E. Jr; Michel, B.E.; Harris, D.G. (1967)."Photosynthesis, transpiration, leaf temperature, and stomatal activity of cotton plants under varying water potentials".Plant Physiology.42(1): 76–88.doi:10.1104/pp.42.1.76.PMC1086491.PMID16656488.

- ^Meena, Vijay Singh; Maurya, Bihari Ram; Verma, Jai Prakash; Aeron, Abhinav; Kumar, Ashok; Kim, Kangmin; Bajpai, Vivek K. (2015)."Potassium solubilizing rhizobacteria (KSR): isolation, identification, and K-release dynamics from waste mica".Ecological Engineering.81:340–47.Bibcode:2015EcEng..81..340M.doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.04.065.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Sawhney, Brij L. (1972)."Selective sorption and fixation of cations by clay minerals: a review".Clays and Clay Minerals.20(2): 93–100.Bibcode:1972CCM....20...93S.doi:10.1346/CCMN.1972.0200208.S2CID101201217.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,pp. 134–35.

- ^Reitemeier 1957,pp. 101–04.

- ^Loide, Valli (2004)."About the effect of the contents and ratios of soil's available calcium, potassium and magnesium in liming of acid soils".Agronomy Research.2(1): 71–82.S2CID28238101.Archived(PDF)from the original on 7 August 2020.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Wuddivira, Mark N.; Camps-Roach, Geremy (2007)."Effects of organic matter and calcium on soil structural stability".European Journal of Soil Science.58(3): 722–27.Bibcode:2007EuJSS..58..722W.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2389.2006.00861.x.S2CID97426847.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,pp. 135–36.

- ^Smith, Garth S.; Cornforth, Ian S. (1982)."Concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur, magnesium, and calcium in North Island pastures in relation to plant and animal nutrition".New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research.25(3): 373–87.Bibcode:1982NZJAR..25..373S.doi:10.1080/00288233.1982.10417901.

- ^White, Philip J.; Broadley, Martin R. (2003)."Calcium in plants".Annals of Botany.92(4): 487–511.doi:10.1093/aob/mcg164.PMC4243668.PMID12933363.

- ^abDonahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,p. 136.

- ^Jarrell, Wesley M.; Beverly, Reuben B. (1981)."The dilution effect in plant nutrition studies".Advances in Agronomy.34:197–224.doi:10.1016/S0065-2113(08)60887-1.ISBN9780120007349.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Jordan & Reisenauer 1957,p. 107.

- ^Holmes & Brown 1957,pp. 111.

- ^Sherman 1957,p. 135.

- ^Seatz & Jurinak 1957,p. 115.

- ^Reuther 1957,p. 128.

- ^Russel 1957,p. 121.

- ^Stout & Johnson 1957,p. 146.

- ^Stout & Johnson 1957,p. 141.

- ^Welsh, Ross M. (1995)."Micronutrient nutrition of plants".Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences.14(1): 49–82.doi:10.1080/713608066.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Summer, Malcolm E.; Farina, Mart P. W. (1986)."Phosphorus interactions with other nutrients and lime in field cropping systems".In Stewart, Bobby A. (ed.).Advances in soil science.Vol. 5. New York, New York: Springer. pp. 201–36.doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8660-5_5.ISBN978-1-4613-8660-5.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Lešková, Alexandra; Giehl, Ricardo F.H.; Hartmann, Anja; Fargašová, Agáta; von Wirén, Nicolaus (2017)."Heavy metals induce iron deficiency responses at different hierarchic and regulatory levels".Plant Physiology.174(3): 1648–68.doi:10.1104/pp.16.01916.PMC5490887.PMID28500270.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^M’Sehli, Wissal; Youssfi, Sabah; Donnini, Silvia; Dell’Orto, Marta; De Nisi, Patricia; Zocchi, Graziano; Abdelly, Chedly; Gharsalli, Mohamed (2008)."Root exudation and rhizosphere acidification by two lines ofMedicago ciliarisin response to lime-induced iron deficiency ".Plant and Soil.312(151): 151–62.Bibcode:2008PlSoi.312..151M.doi:10.1007/s11104-008-9638-9.S2CID12585193.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Donahue, Miller & Shickluna 1977,pp. 136–37.

- ^Stout & Johnson 1957,p. 107.

- ^Pereira, B.F. Faria; He, Zhenli; Stoffella, Peter J.; Montes, Celia R.; Melfi, Adolpho J.; Baligar, Virupax C. (2012)."Nutrients and nonessential elements in soil after 11 years of wastewater irrigation".Journal of Environmental Quality.41(3): 920–27.Bibcode:2012JEnvQ..41..920P.doi:10.2134/jeq2011.0047.PMID22565273.Retrieved10 December2023.

- ^Richmond, Kathryn E.; Sussman, Michael (2003)."Got silicon? The non-essential beneficial plant nutrient".Current Opinion in Plant Biology.6(3): 268–72.Bibcode:2003COPB....6..268R.doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00041-4.PMID12753977.Retrieved10 December2023.

Bibliography[edit]

- Donahue, Roy Luther; Miller, Raymond W.; Shickluna, John C. (1977).Soils: An Introduction to Soils and Plant Growth.Prentice-Hall.ISBN978-0-13-821918-5.

- "Arizona Master Gardener".Cooperative Extension, College of Agriculture, University of Arizona.Retrieved27 May2013.

- Stefferud, Alfred, ed. (1957).Soil: The Yearbook of Agriculture 1957.United States Department of Agriculture.OCLC704186906.

- Kellogg. "We Seek; We Learn".InStefferud (1957).

- Simonson. "What Soils Are".InStefferud (1957).

- Russell. "Physical Properties".InStefferud (1957).

- Richards & Richards. "Soil Moisture".InStefferud (1957).

- Wadleigh. "Growth of Plants".InStefferud (1957).

- Allaway. "pH, Soil Acidity, and Plant Growth".InStefferud (1957).

- Coleman & Mehlich. "The Chemistry of Soil pH".InStefferud (1957).

- Dean. "Plant Nutrition and Soil Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Allison. "Nitrogen and Soil Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Olsen & Fried. "Soil Phosphorus and Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Reitemeier. "Soil Potassium and Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Jordan & Reisenauer. "Sulfur and Soil Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Holmes & Brown. "Iron and Soil Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Seatz & Jurinak. "Zinc and Soil Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Russel. "Boron and Soil Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Reuther. "Copper and Soil Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Sherman. "Manganese and Soil Fertility".InStefferud (1957).

- Stout & Johnson. "Trace Elements".InStefferud (1957).

- Broadbent. "Organic Matter".InStefferud (1957).

- Clark. "Living Organisms in the Soil".InStefferud (1957).

- Flemming. "Soil Management and Insect Control".InStefferud (1957).