Poetry

| Literature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Oral literature | ||||||

| Major written forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Prose genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Poetry genres | ||||||

|

||||||

| Dramatic genres | ||||||

| History | ||||||

| Lists and outlines | ||||||

| Theoryandcriticism | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Poetry(from theGreekwordpoiesis,"making" ) is a form ofliterary artthat usesaestheticand oftenrhythmic[1][2][3]qualities oflanguageto evokemeaningsin addition to, or in place of,literalor surface-level meanings. Any particular instance of poetry is called apoemand is written by apoet.Poets use a variety of techniques called poetic devices, such asassonance,alliteration,euphony and cacophony,onomatopoeia,rhythm(viametre), andsound symbolism,to producemusicalor other artistic effects. Most written poems are formatted inverse:a series or stack oflineson a page, which follow a rhythmic or other deliberate structure. For this reason,versehas also become asynonym(ametonym) for poetry.[note 1]

Poetry has a long and variedhistory,evolving differentially across the globe. It dates back at least to prehistoric times with hunting poetry inAfricaand topanegyricandelegiaccourt poetry of the empires of theNile,Niger,andVolta Rivervalleys.[4]Some of the earliest written poetry in Africa occurs among thePyramid Textswritten during the 25th century BCE. The earliest surviving Western Asianepic poem,theEpic of Gilgamesh,was written in theSumerian language.

Early poems in theEurasiancontinent evolved from folk songs such as the ChineseShijingas well as from religioushymns(theSanskritRigveda,theZoroastrianGathas,theHurrian songs,and the HebrewPsalms); or from a need to retell oral epics, as with the EgyptianStory of Sinuhe,Indian epic poetry,and theHomericepics, theIliadand theOdyssey.

Ancient Greek attempts to define poetry, such asAristotle'sPoetics,focused on the uses ofspeechinrhetoric,drama,song,andcomedy.Later attempts concentrated on features such asrepetition,verse form,andrhyme,and emphasized aesthetics which distinguish poetry from the format of more objectively-informative, academic, or typical writing, which is known asprose.

Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest differentialinterpretationsof words, or to evokeemotiveresponses. The use ofambiguity,symbolism,irony,and otherstylisticelements ofpoetic dictionoften leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations. Similarly, figures of speech such asmetaphor,simile,andmetonymy[5]establish a resonance between otherwise disparate images—a layering of meanings, forming connections previously not perceived. Kindred forms of resonance may exist, between individualverses,in their patterns of rhyme or rhythm.

Some poetry types are unique to particularculturesandgenresand respond to characteristics of the language in which the poet writes. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry withDante,Goethe,Mickiewicz,orRumimay think of it as written inlinesbased onrhymeand regularmeter.There are, however, traditions, such asBiblical poetryandalliterative verse,that use other means to create rhythm andeuphony.Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition,[6]testing the principle of euphony itself or altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm.[7][8]

Poets – as, from theGreek,"makers" of language – have contributed to the evolution of the linguistic, expressive, and utilitarian qualities of their languages. In an increasinglyglobalizedworld, poets often adapt forms, styles, and techniques from diverse cultures and languages.

AWestern culturaltradition (extending at least fromHomertoRilke) associates the production of poetry withinspiration– often by aMuse(either classical or contemporary), or through other (often canonised) poets' work which sets some kind of example or challenge.

In first-person poems, the lyrics are spoken by an "I", acharacterwho may be termed thespeaker,distinct from thepoet(theauthor). Thus if, for example, a poem asserts, "I killed my enemy in Reno", it is the speaker, not the poet, who is the killer (unless this "confession" is a form ofmetaphorwhich needs to be considered in closercontext– viaclose reading).

History

[edit]Early works

[edit]Some scholars believe that the art of poetry may predateliteracy,and developed from folkepicsand other oral genres.[9][10] Others, however, suggest that poetry did not necessarily predate writing.[11]

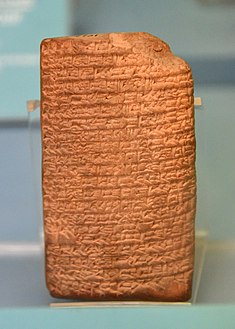

The oldest surviving epic poem, theEpic of Gilgamesh,dates from the 3rd millenniumBCE inSumer(inMesopotamia,present-dayIraq), and was written incuneiformscript on clay tablets and, later, onpapyrus.[12]TheIstanbul tablet#2461,dating toc.2000BCE, describes an annual rite in which the kingsymbolically marriedand mated with the goddessInannato ensure fertility and prosperity; some have labelled it the world's oldest love poem.[13][14]An example of Egyptian epic poetry isThe Story of Sinuhe(c. 1800 BCE).[15]

Other ancient epics includes the GreekIliadand theOdyssey;the PersianAvestanbooks (theYasna); theRomannational epic,Virgil'sAeneid(written between 29 and 19 BCE); and theIndian epics,theRamayanaand theMahabharata.Epic poetry appears to have been composed in poetic form as an aid to memorization and oral transmission in ancient societies.[11][16]

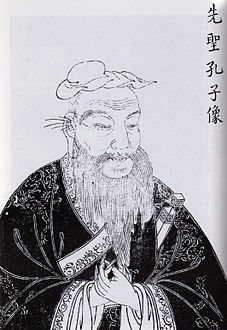

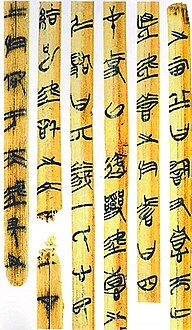

Other forms of poetry, including such ancient collections of religioushymnsas the IndianSanskrit-languageRigveda,the AvestanGathas,theHurrian songs,and the HebrewPsalms,possibly developed directly fromfolk songs.The earliest entries in the oldest extant collection ofChinese poetry,theClassic of Poetry(Shijing), were initiallylyrics.[17]The Shijing, with its collection of poems and folk songs, was heavily valued by the philosopherConfuciusand is considered to be one of the officialConfucian classics.His remarks on the subject have become an invaluable source inancient music theory.[18]

The efforts of ancient thinkers to determine what makes poetry distinctive as a form, and what distinguishes good poetry from bad, resulted in "poetics"—the study of the aesthetics of poetry.[19]Some ancient societies, such as China's through theShijing,developed canons of poetic works that had ritual as well as aesthetic importance.[20]More recently, thinkers have struggled to find a definition that could encompass formal differences as great as those between Chaucer'sCanterbury TalesandMatsuo Bashō'sOku no Hosomichi,as well as differences in content spanningTanakhreligious poetry,love poetry, andrap.[21]

Until recently, the earliest examples ofstressed poetryhad been thought to be works composed byRomanos the Melodist(fl.6th century CE). However,Tim Whitmarshwrites that an inscribed Greek poem predated Romanos' stressed poetry.[22][23][24]

-

The oldest known love poem. Sumerianterracotta tablet#2461from Nippur, Iraq. Ur III period, 2037–2029 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul

-

The philosopherConfuciuswas influential in the developed approach to poetry andancient music theory.

Western traditions

[edit]

Classical thinkers in theWestemployed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. Notably, the existing fragments ofAristotle'sPoeticsdescribe three genres of poetry—the epic, the comic, and the tragic—and develop rules to distinguish the highest-quality poetry in each genre, based on the perceived underlying purposes of the genre.[25]Lateraestheticiansidentified three major genres: epic poetry,lyric poetry,anddramatic poetry,treatingcomedyandtragedyassubgenresof dramatic poetry.[26]

Aristotle's work was influential throughout the Middle East during theIslamic Golden Age,[27]as well as in Europe during theRenaissance.[28]Later poets and aestheticians often distinguished poetry from, and defined it in opposition toprose,which they generally understood as writing with a proclivity to logical explication and a linear narrative structure.[29]

This does not imply that poetry is illogical or lacks narration, but rather that poetry is an attempt to render the beautiful or sublime without the burden of engaging the logical or narrative thought-process. EnglishRomanticpoetJohn Keatstermed this escape from logic "negative capability".[30]This "romantic" approach viewsformas a key element of successful poetry because form is abstract and distinct from the underlying notional logic. This approach remained influential into the 20th century.[31]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, there was also substantially more interaction among the various poetic traditions, in part due to the spread of Europeancolonialismand the attendant rise in global trade.[32]In addition to a boom intranslation,during the Romantic period numerous ancient works were rediscovered.[33]

20th-century and 21st-century disputes

[edit]

Some 20th-centuryliterary theoristsrely less on the ostensible opposition of prose and poetry, instead focusing on the poet as simply one whocreatesusing language, and poetry as what the poet creates.[34]The underlying concept of the poet ascreatoris not uncommon, and somemodernist poetsessentially do not distinguish between the creation of a poem with words, and creative acts in other media. Other modernists challenge the very attempt to define poetry as misguided.[35]

The rejection of traditional forms and structures for poetry that began in the first half of the 20th century coincided with a questioning of the purpose and meaning of traditional definitions of poetry and of distinctions between poetry and prose, particularly given examples of poetic prose and prosaic poetry. Numerous modernist poets have written in non-traditional forms or in what traditionally would have been considered prose, although their writing was generally infused with poetic diction and often with rhythm andtoneestablished bynon-metricalmeans. While there was a substantialformalistreaction within the modernist schools to the breakdown of structure, this reaction focused as much on the development of new formal structures and syntheses as on the revival of older forms and structures.[36]

Postmodernismgoes beyond modernism's emphasis on the creative role of the poet, to emphasize the role of the reader of a text (hermeneutics), and to highlight the complex cultural web within which a poem is read.[37]Today, throughout the world, poetry often incorporates poetic form and diction from other cultures and from the past, further confounding attempts at definition and classification that once made sense within a tradition such as theWestern canon.[38]

The early 21st-century poetic tradition appears to continue to strongly orient itself to earlier precursor poetic traditions such as those initiated byWhitman,Emerson,andWordsworth.The literary criticGeoffrey Hartman(1929–2016) used the phrase "the anxiety of demand" to describe the contemporary response to older poetic traditions as "being fearful that the fact no longer has a form",[39]building on a trope introduced by Emerson. Emerson had maintained that in the debate concerning poetic structure where either "form" or "fact" could predominate, that one need simply "Ask the fact for the form." This has been challenged at various levels by other literary scholars such asHarold Bloom(1930–2019), who has stated: "The generation of poets who stand together now, mature and ready to write the major American verse of the twenty-first century, may yet be seen as what Stevens called 'a great shadow's last embellishment,' the shadow being Emerson's."[40]

Elements

[edit]Prosody

[edit]Prosody is the study of the meter,rhythm,andintonationof a poem. Rhythm and meter are different, although closely related.[41]Meter is the definitive pattern established for a verse (such asiambic pentameter), while rhythm is the actual sound that results from a line of poetry. Prosody also may be used more specifically to refer to thescanningof poetic lines to show meter.[42]

Rhythm

[edit]

The methods for creating poetic rhythm vary across languages and between poetic traditions. Languages are often described as having timing set primarily byaccents,syllables,ormoras,depending on how rhythm is established, although a language can be influenced by multiple approaches.Japaneseis amora-timed language.Latin,Catalan,French,Leonese,GalicianandSpanishare called syllable-timed languages. Stress-timed languages includeEnglish,Russianand, generally,German.[43]Varyingintonationalso affects how rhythm is perceived. Languages can rely on either pitch or tone. Some languages with a pitch accent are Vedic Sanskrit or Ancient Greek.Tonal languagesinclude Chinese, Vietnamese and mostSubsaharan languages.[44]

Metrical rhythm generally involves precise arrangements of stresses or syllables into repeated patterns calledfeetwithin a line. In Modern English verse the pattern of stresses primarily differentiate feet, so rhythm based on meter in Modern English is most often founded on the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables (alone orelided).[45]In theclassical languages,on the other hand, while themetricalunits are similar,vowel lengthrather than stresses define the meter.[46]Old Englishpoetry used a metrical pattern involving varied numbers of syllables but a fixed number of strong stresses in each line.[47]

The chief device of ancientHebrewBiblical poetry,including many of thepsalms,wasparallelism,a rhetorical structure in which successive lines reflected each other in grammatical structure, sound structure, notional content, or all three. Parallelism lent itself toantiphonalorcall-and-responseperformance, which could also be reinforced byintonation.Thus, Biblical poetry relies much less on metrical feet to create rhythm, but instead creates rhythm based on much larger sound units of lines, phrases and sentences.[48]Some classical poetry forms, such asVenpaof theTamil language,had rigid grammars (to the point that they could be expressed as acontext-free grammar) which ensured a rhythm.[49]

Classical Chinese poetics,based on thetone system of Middle Chinese,recognized two kinds of tones: the level ( bìnhpíng) tone and the oblique ( trắczè) tones, a category consisting of the rising ( thượngsháng) tone, the departing ( khứqù) tone and the entering ( nhậprù) tone. Certain forms of poetry placed constraints on which syllables were required to be level and which oblique.

The formal patterns of meter used in Modern English verse to create rhythm no longer dominate contemporary English poetry. In the case offree verse,rhythm is often organized based on looser units ofcadencerather than a regular meter.Robinson Jeffers,Marianne Moore,andWilliam Carlos Williamsare three notable poets who reject the idea that regular accentual meter is critical to English poetry.[50]Jeffers experimented withsprung rhythmas an alternative to accentual rhythm.[51]

Meter

[edit]

In the Western poetic tradition, meters are customarily grouped according to a characteristicmetrical footand the number of feet per line.[53]The number of metrical feet in a line are described using Greek terminology:tetrameterfor four feet andhexameterfor six feet, for example.[54]Thus, "iambic pentameter"is a meter comprising five feet per line, in which the predominant kind of foot is the"iamb".This metric system originated in ancientGreek poetry,and was used by poets such asPindarandSappho,and by the greattragediansofAthens.Similarly, "dactylic hexameter",comprises six feet per line, of which the dominant kind of foot is the"dactyl".Dactylic hexameter was the traditional meter of Greekepic poetry,the earliest extant examples of which are the works ofHomerandHesiod.[55]Iambic pentameter and dactylic hexameter were later used by a number of poets, includingWilliam ShakespeareandHenry Wadsworth Longfellow,respectively.[56]The most common metrical feet in English are:[57]

- iamb– one unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (e.g. des-cribe,in-clude,re-tract)

- trochee—one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable (e.g.pic-ture,flow-er)

- dactyl– one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables (e.g.an-no-tate,sim-i-lar)

- anapaest—two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable (e.g. com-pre-hend)

- spondee—two stressed syllables together (e.g.heart-beat,four-teen)

- pyrrhic—two unstressed syllables together (rare, usually used to end dactylic hexameter)

There are a wide range of names for other types of feet, right up to achoriamb,a four syllable metric foot with a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables and closing with a stressed syllable. The choriamb is derived from some ancientGreekandLatin poetry.[55]Languages which usevowel lengthorintonationrather than or in addition to syllabic accents in determining meter, such asOttoman TurkishorVedic,often have concepts similar to the iamb and dactyl to describe common combinations of long and short sounds.[59]

Each of these types of feet has a certain "feel," whether alone or in combination with other feet. The iamb, for example, is the most natural form of rhythm in the English language, and generally produces a subtle but stable verse.[60]Scanning meter can often show the basic or fundamental pattern underlying a verse, but does not show the varying degrees ofstress,as well as the differing pitches andlengthsof syllables.[61]

There is debate over how useful a multiplicity of different "feet" is in describing meter. For example,Robert Pinskyhas argued that while dactyls are important in classical verse, English dactylic verse uses dactyls very irregularly and can be better described based on patterns of iambs and anapests, feet which he considers natural to the language.[62]Actual rhythm is significantly more complex than the basic scanned meter described above, and many scholars have sought to develop systems that would scan such complexity.Vladimir Nabokovnoted that overlaid on top of the regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of verse was a separate pattern of accents resulting from the natural pitch of the spoken words, and suggested that the term "scud" be used to distinguish an unaccented stress from an accented stress.[63]

Metrical patterns

[edit]

Different traditions and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespeareaniambic pentameterand the Homericdactylic hexameterto theanapestic tetrameterused in many nursery rhymes. However, a number of variations to the established meter are common, both to provide emphasis or attention to a given foot or line and to avoid boring repetition. For example, the stress in a foot may be inverted, acaesura(or pause) may be added (sometimes in place of a foot or stress), or the final foot in a line may be given afeminine endingto soften it or be replaced by aspondeeto emphasize it and create a hard stop. Some patterns (such as iambic pentameter) tend to be fairly regular, while other patterns, such as dactylic hexameter, tend to be highly irregular.[64]Regularity can vary between language. In addition, different patterns often develop distinctively in different languages, so that, for example,iambic tetrameterin Russian will generally reflect a regularity in the use of accents to reinforce the meter, which does not occur, or occurs to a much lesser extent, in English.[65]

Some common metrical patterns, with notable examples of poets and poems who use them, include:

- Iambic pentameter(John Milton,Paradise Lost;William Shakespeare,Sonnets)[66]

- Dactylic hexameter(Homer,Iliad;Virgil,Aeneid)[67]

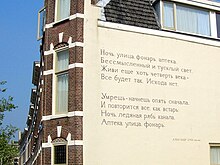

- Iambic tetrameter(Andrew Marvell,"To His Coy Mistress";Alexander Pushkin,Eugene Onegin;Robert Frost,Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening)[68]

- Trochaic octameter(Edgar Allan Poe,"The Raven")[69]

- Trochaic tetrameter(Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,The Song of Hiawatha;the Finnish national epic,The Kalevala,is also in trochaic tetrameter, the natural rhythm of Finnish and Estonian)

- Alexandrin(Jean Racine,Phèdre)[70]

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance

[edit]

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance andconsonanceare ways of creating repetitive patterns of sound. They may be used as an independent structural element in a poem, to reinforce rhythmic patterns, or as an ornamental element.[71]They can also carry a meaning separate from the repetitive sound patterns created. For example,Chaucerused heavy alliteration to mock Old English verse and to paint a character as archaic.[72]

Rhyme consists of identical ( "hard-rhyme" ) or similar ( "soft-rhyme" ) sounds placed at the ends of lines or at locations within lines ( "internal rhyme"). Languages vary in the richness of their rhyming structures; Italian, for example, has a rich rhyming structure permitting maintenance of a limited set of rhymes throughout a lengthy poem. The richness results from word endings that follow regular forms. English, with its irregular word endings adopted from other languages, is less rich in rhyme.[73]The degree of richness of a language's rhyming structures plays a substantial role in determining what poetic forms are commonly used in that language.[74]

Alliteration is the repetition of letters or letter-sounds at the beginning of two or more words immediately succeeding each other, or at short intervals; or the recurrence of the same letter in accented parts of words. Alliteration and assonance played a key role in structuring early Germanic, Norse and Old English forms of poetry. The alliterative patterns of early Germanic poetry interweave meter and alliteration as a key part of their structure, so that the metrical pattern determines when the listener expects instances of alliteration to occur. This can be compared to an ornamental use of alliteration in most Modern European poetry, where alliterative patterns are not formal or carried through full stanzas. Alliteration is particularly useful in languages with less rich rhyming structures.

Assonance, where the use of similar vowel sounds within a word rather than similar sounds at the beginning or end of a word, was widely used inskaldicpoetry but goes back to the Homeric epic.[75]Because verbs carry much of the pitch in the English language, assonance can loosely evoke the tonal elements of Chinese poetry and so is useful in translating Chinese poetry.[76]Consonance occurs where a consonant sound is repeated throughout a sentence without putting the sound only at the front of a word. Consonance provokes a more subtle effect than alliteration and so is less useful as a structural element.[74]

Rhyming schemes

[edit]

In many languages, including Arabic and modern European languages, poets use rhyme in set patterns as a structural element for specific poetic forms, such asballads,sonnetsandrhyming couplets.However, the use of structural rhyme is not universal even within the European tradition. Much modern poetry avoids traditionalrhyme schemes.Classical Greek and Latin poetry did not use rhyme.[77]Rhyme entered European poetry in theHigh Middle Ages,due to the influence of theArabic languageinAl Andalus.[78]Arabic language poets used rhyme extensively not only with the development of literary Arabic in thesixth century,but also with the much older oral poetry, as in their long, rhymingqasidas.[79]Some rhyming schemes have become associated with a specific language, culture or period, while other rhyming schemes have achieved use across languages, cultures or time periods. Some forms of poetry carry a consistent and well-defined rhyming scheme, such as thechant royalor therubaiyat,while other poetic forms have variable rhyme schemes.[80]

Most rhyme schemes are described using letters that correspond to sets of rhymes, so if the first, second and fourth lines of a quatrain rhyme with each other and the third line do not rhyme, the quatrain is said to have an AA BArhyme scheme.This rhyme scheme is the one used, for example, in the rubaiyat form.[81]Similarly, an A BB A quatrain (what is known as "enclosed rhyme") is used in such forms as thePetrarchan sonnet.[82]Some types of more complicated rhyming schemes have developed names of their own, separate from the "a-bc" convention, such as theottava rimaandterza rima.[83]The types and use of differing rhyming schemes are discussed further in themain article.

Form in poetry

[edit]Poetic form is more flexible in modernist and post-modernist poetry and continues to be less structured than in previous literary eras. Many modern poets eschew recognizable structures or forms and write infree verse.Free verse is, however, not "formless" but composed of a series of more subtle, more flexible prosodic elements.[84]Thus poetry remains, in all its styles, distinguished from prose by form;[85]some regard for basic formal structures of poetry will be found in all varieties of free verse, however much such structures may appear to have been ignored.[86]Similarly, in the best poetry written in classic styles there will be departures from strict form for emphasis or effect.[87]

Among major structural elements used in poetry are the line, thestanzaorverse paragraph,and larger combinations of stanzas or lines such ascantos.Also sometimes used are broader visual presentations of words andcalligraphy.These basic units of poetic form are often combined into larger structures, calledpoetic formsor poetic modes (see the following section), as in thesonnet.

Lines and stanzas

[edit]Poetry is often separated into lines on a page, in a process known aslineation.These lines may be based on the number of metrical feet or may emphasize a rhyming pattern at the ends of lines. Lines may serve other functions, particularly where the poem is not written in a formal metrical pattern. Lines can separate, compare or contrast thoughts expressed in different units, or can highlight a change in tone.[88]See the article online breaksfor information about the division between lines.

Lines of poems are often organized intostanzas,which are denominated by the number of lines included. Thus a collection of two lines is acouplet(ordistich), three lines atriplet(ortercet), four lines aquatrain,and so on. These lines may or may not relate to each other by rhyme or rhythm. For example, a couplet may be two lines with identical meters which rhyme or two lines held together by a common meter alone.[89]

Other poems may be organized intoverse paragraphs,in which regular rhymes with established rhythms are not used, but the poetic tone is instead established by a collection of rhythms, alliterations, and rhymes established in paragraph form.[90]Many medieval poems were written in verse paragraphs, even where regular rhymes and rhythms were used.[91]

In many forms of poetry, stanzas are interlocking, so that the rhyming scheme or other structural elements of one stanza determine those of succeeding stanzas. Examples of such interlocking stanzas include, for example, theghazaland thevillanelle,where a refrain (or, in the case of the villanelle, refrains) is established in the first stanza which then repeats in subsequent stanzas. Related to the use of interlocking stanzas is their use to separate thematic parts of a poem. For example, thestrophe,antistropheandepodeof the ode form are often separated into one or more stanzas.[92]

In some cases, particularly lengthier formal poetry such as some forms of epic poetry, stanzas themselves are constructed according to strict rules and then combined. Inskaldicpoetry, thedróttkvættstanza had eight lines, each having three "lifts" produced with alliteration or assonance. In addition to two or three alliterations, the odd-numbered lines had partial rhyme of consonants with dissimilar vowels, not necessarily at the beginning of the word; the even lines contained internal rhyme in set syllables (not necessarily at the end of the word). Each half-line had exactly six syllables, and each line ended in a trochee. The arrangement of dróttkvætts followed far less rigid rules than the construction of the individual dróttkvætts.[93]

Visual presentation

[edit]Even before the advent of printing, the visual appearance of poetry often added meaning or depth.Acrosticpoems conveyed meanings in the initial letters of lines or in letters at other specific places in a poem.[94]InArabic,HebrewandChinese poetry,the visual presentation of finelycalligraphedpoems has played an important part in the overall effect of many poems.[95]

With the advent ofprinting,poets gained greater control over the mass-produced visual presentations of their work. Visual elements have become an important part of the poet's toolbox, and many poets have sought to use visual presentation for a wide range of purposes. SomeModernistpoets have made the placement of individual lines or groups of lines on the page an integral part of the poem's composition. At times, this complements the poem'srhythmthrough visualcaesurasof various lengths, or createsjuxtapositionsso as to accentuate meaning,ambiguityorirony,or simply to create an aesthetically pleasing form. In its most extreme form, this can lead toconcrete poetryorasemic writing.[96][97]

Diction

[edit]Poetic diction treats the manner in which language is used, and refers not only to the sound but also to the underlying meaning and its interaction with sound and form.[98]Many languages and poetic forms have very specific poetic dictions, to the point where distinctgrammarsanddialectsare used specifically for poetry.[99][100]Registersin poetry can range from strict employment of ordinary speech patterns, as favoured in much late-20th-centuryprosody,[101]through to highly ornate uses of language, as in medieval and Renaissance poetry.[102]

Poetic diction can includerhetorical devicessuch assimileandmetaphor,as well as tones of voice, such asirony.Aristotlewrote in thePoeticsthat "the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor."[103]Since the rise ofModernism,some poets have opted for a poetic diction that de-emphasizes rhetorical devices, attempting instead the direct presentation of things and experiences and the exploration oftone.[104]On the other hand,Surrealistshave pushed rhetorical devices to their limits, making frequent use ofcatachresis.[105]

Allegoricalstories are central to the poetic diction of many cultures, and were prominent in the West during classical times, thelate Middle Agesand theRenaissance.Aesop's Fables,repeatedly rendered in both verse and prose since first being recorded about 500 BCE, are perhaps the richest single source of allegorical poetry through the ages.[106]Other notables examples include theRoman de la Rose,a 13th-century French poem,William Langland'sPiers Ploughmanin the 14th century, andJean de la Fontaine'sFables(influenced by Aesop's) in the 17th century. Rather than being fully allegorical, however, a poem may containsymbolsorallusionsthat deepen the meaning or effect of its words without constructing a full allegory.[107]

Another element of poetic diction can be the use of vividimageryfor effect. The juxtaposition of unexpected or impossible images is, for example, a particularly strong element in surrealist poetry andhaiku.[108]Vivid images are often endowed with symbolism or metaphor. Many poetic dictions use repetitive phrases for effect, either a short phrase (such as Homer's "rosy-fingered dawn" or "the wine-dark sea" ) or a longerrefrain.Such repetition can add a somber tone to a poem, or can be laced with irony as the context of the words changes.[109]

Forms

[edit]

Specific poetic forms have been developed by many cultures. In more developed, closed or "received" poetic forms, the rhyming scheme, meter and other elements of a poem are based on sets of rules, ranging from the relatively loose rules that govern the construction of anelegyto the highly formalized structure of theghazalorvillanelle.[110]Described below are some common forms of poetry widely used across a number of languages. Additional forms of poetry may be found in the discussions of the poetry of particular cultures or periods and in theglossary.

Sonnet

[edit]

Among the most common forms of poetry, popular from theLate Middle Ageson, is the sonnet, which by the 13th century had become standardized as fourteen lines following a set rhyme scheme and logical structure. By the 14th century and theItalian Renaissance,the form had further crystallized under the pen ofPetrarch,whose sonnets were translated in the 16th century bySir Thomas Wyatt,who is credited with introducing the sonnet form into English literature.[111]A traditional Italian orPetrarchan sonnetfollows the rhyme schemeABBA, ABBA, CDECDE,though some variation, perhaps the most common being CDCDCD, especially within the final six lines (orsestet), is common.[112]TheEnglish (or Shakespearean) sonnetfollows the rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, introducing a thirdquatrain(grouping of four lines), a finalcouplet,and a greater amount of variety in rhyme than is usually found in its Italian predecessors. By convention, sonnets in English typically useiambic pentameter,while in theRomance languages,thehendecasyllableandAlexandrineare the most widely used meters.

Sonnets of all types often make use of avolta,or "turn," a point in the poem at which an idea is turned on its head, a question is answered (or introduced), or the subject matter is further complicated. Thisvoltacan often take the form of a "but" statement contradicting or complicating the content of the earlier lines. In the Petrarchan sonnet, the turn tends to fall around the division between the first two quatrains and the sestet, while English sonnets usually place it at or near the beginning of the closing couplet.

Sonnets are particularly associated with high poetic diction, vivid imagery, and romantic love, largely due to the influence of Petrarch as well as of early English practitioners such asEdmund Spenser(who gave his name to theSpenserian sonnet),Michael Drayton,and Shakespeare, whosesonnetsare among the most famous in English poetry, with twenty being included in theOxford Book of English Verse.[113]However, the twists and turns associated with thevoltaallow for a logical flexibility applicable to many subjects.[114]Poets from the earliest centuries of the sonnet to the present have used the form to address topics related to politics (John Milton,Percy Bysshe Shelley,Claude McKay), theology (John Donne,Gerard Manley Hopkins), war (Wilfred Owen,E. E. Cummings), and gender and sexuality (Carol Ann Duffy). Further, postmodern authors such asTed BerriganandJohn Berrymanhave challenged the traditional definitions of the sonnet form, rendering entire sequences of "sonnets" that often lack rhyme, a clear logical progression, or even a consistent count of fourteen lines.

Shi

[edit]

Shi(simplified Chinese:Thi;traditional Chinese:Thi;pinyin:shī;Wade–Giles:shih) Is the main type ofClassical Chinese poetry.[115]Within this form of poetry the most important variations are "folk song" styled verse (yuefu), "old style" verse (gushi), "modern style" verse (jintishi). In all cases, rhyming is obligatory. The Yuefu is a folk ballad or a poem written in the folk ballad style, and the number of lines and the length of the lines could be irregular. For the other variations ofshipoetry, generally either a four line (quatrain, orjueju) or else an eight-line poem is normal; either way with the even numbered lines rhyming. The line length is scanned by an according number of characters (according to the convention that one character equals one syllable), and are predominantly either five or seven characters long, with acaesurabefore the final three syllables. The lines are generally end-stopped, considered as a series of couplets, and exhibit verbal parallelism as a key poetic device.[116]The "old style" verse (Gushi) is less formally strict than thejintishi,or regulated verse, which, despite the name "new style" verse actually had its theoretical basis laid as far back asShen Yue(441–513 CE), although not considered to have reached its full development until the time ofChen Zi'ang(661–702 CE).[117]A good example of a poet known for hisGushipoems isLi Bai(701–762 CE). Among its other rules, the jintishi rules regulate the tonal variations within a poem, including the use of set patterns of thefour tonesofMiddle Chinese.The basic form of jintishi (sushi) has eight lines in four couplets, with parallelism between the lines in the second and third couplets. The couplets with parallel lines contain contrasting content but an identical grammatical relationship between words. Jintishi often have a rich poetic diction, full ofallusion,and can have a wide range of subject, including history and politics.[118][119]One of the masters of the form wasDu Fu(712–770 CE), who wrote during the Tang Dynasty (8th century).[120]

Villanelle

[edit]

The villanelle is a nineteen-line poem made up of five triplets with a closing quatrain; the poem is characterized by having two refrains, initially used in the first and third lines of the first stanza, and then alternately used at the close of each subsequent stanza until the final quatrain, which is concluded by the two refrains. The remaining lines of the poem have an AB alternating rhyme.[121]The villanelle has been used regularly in the English language since the late 19th century by such poets asDylan Thomas,[122]W. H. Auden,[123]andElizabeth Bishop.[124]

Limerick

[edit]A limerick is a poem that consists of five lines and is often humorous. Rhythm is very important in limericks for the first, second and fifth lines must have seven to ten syllables. However, the third and fourth lines only need five to seven. Lines 1, 2 and 5 rhyme with each other, and lines 3 and 4 rhyme with each other. Practitioners of the limerick includedEdward Lear,Lord Alfred Tennyson,Rudyard Kipling,Robert Louis Stevenson.[125]

Tanka

[edit]

Tanka is a form of unrhymedJapanese poetry,with five sections totalling 31on(phonological units identical tomorae), structured in a 5–7–5–7–7 pattern.[126]There is generally a shift in tone and subject matter between the upper 5–7–5 phrase and the lower 7–7 phrase. Tanka were written as early as theAsuka periodby such poets asKakinomoto no Hitomaro(fl.late 7th century), at a time when Japan was emerging from a period where much of its poetry followed Chinese form.[127]Tanka was originally the shorter form of Japanese formal poetry (which was generally referred to as "waka"), and was used more heavily to explore personal rather than public themes. By the tenth century, tanka had become the dominant form of Japanese poetry, to the point where the originally general termwaka( "Japanese poetry" ) came to be used exclusively for tanka. Tanka are still widely written today.[128]

Haiku

[edit]Haiku is a popular form of unrhymed Japanese poetry, which evolved in the 17th century from thehokku,or opening verse of arenku.[129]Generally written in a single vertical line, the haiku contains three sections totalling 17on(morae), structured in a 5–7–5 pattern. Traditionally, haiku contain akireji,or cutting word, usually placed at the end of one of the poem's three sections, and akigo,or season-word.[130]The most famous exponent of the haiku wasMatsuo Bashō(1644–1694). An example of his writing:[131]

- Phú sĩ の phong や phiến にのせて giang hộ thổ sản

- fuji no kaze ya oogi ni nosete Edo miyage

- the wind of Mt. Fuji

- I've brought on my fan!

- a gift from Edo

Khlong

[edit]Thekhlong(โคลง,[kʰlōːŋ]) is among the oldest Thai poetic forms. This is reflected in its requirements on the tone markings of certain syllables, which must be marked withmai ek(ไม้เอก,Thai pronunciation:[májèːk],◌่) ormai tho(ไม้โท,[májtʰōː],◌้). This was likely derived from when the Thai language had three tones (as opposed to today's five, a split which occurred during theAyutthaya Kingdomperiod), two of which corresponded directly to the aforementioned marks. It is usually regarded as an advanced and sophisticated poetic form.[132]

Inkhlong,a stanza (bot,บท,Thai pronunciation:[bòt]) has a number of lines (bat,บาท,Thai pronunciation:[bàːt],fromPaliandSanskritpāda), depending on the type. Thebatare subdivided into twowak(วรรค,Thai pronunciation:[wák],from Sanskritvarga).[note 2]The firstwakhas five syllables, the second has a variable number, also depending on the type, and may be optional. The type ofkhlongis named by the number ofbatin a stanza; it may also be divided into two main types:khlong suphap(โคลงสุภาพ,[kʰlōːŋsù.pʰâːp]) andkhlong dan(โคลงดั้น,[kʰlōːŋdân]). The two differ in the number of syllables in the secondwakof the finalbatand inter-stanza rhyming rules.[132]

Khlong si suphap

[edit]Thekhlong si suphap(โคลงสี่สุภาพ,[kʰlōːŋsìːsù.pʰâːp]) is the most common form still currently employed. It has fourbatper stanza (sitranslates asfour). The firstwakof eachbathas five syllables. The secondwakhas two or four syllables in the first and thirdbat,two syllables in the second, and four syllables in the fourth.Mai ekis required for seven syllables andMai thois required for four, as shown below. "Dead word"syllables are allowed in place of syllables which requiremai ek,and changing the spelling of words to satisfy the criteria is usually acceptable.

Ode

[edit]

Odes were first developed by poets writing in ancient Greek, such asPindar,and Latin, such asHorace.Forms of odes appear in many of the cultures that were influenced by the Greeks and Latins.[133]The ode generally has three parts: astrophe,anantistrophe,and anepode.The strophe and the antistrophe of the ode possess similar metrical structures and, depending on the tradition, similar rhyme structures. In contrast, the epode is written with a different scheme and structure. Odes have a formal poetic diction and generally deal with a serious subject. The strophe and antistrophe look at the subject from different, often conflicting, perspectives, with the epode moving to a higher level to either view or resolve the underlying issues. Odes are often intended to be recited or sung by two choruses (or individuals), with the first reciting the strophe, the second the antistrophe, and both together the epode.[134]Over time, differing forms for odes have developed with considerable variations in form and structure, but generally showing the original influence of the Pindaric or Horatian ode. One non-Western form which resembles the ode is theqasidainArabic poetry.[135]

Ghazal

[edit]Theghazal(alsoghazel,gazel,gazal,orgozol) is a form of poetry common inArabic,Bengali,PersianandUrdu.In classic form, theghazalhas from five to fifteen rhyming couplets that share arefrainat the end of the second line. This refrain may be of one or several syllables and is preceded by a rhyme. Each line has an identical meter and is of the same length.[136]The ghazal often reflects on a theme of unattainable love or divinity.[137]

As with other forms with a long history in many languages, many variations have been developed, including forms with a quasi-musical poetic diction inUrdu.[138]Ghazals have a classical affinity withSufism,and a number of major Sufi religious works are written in ghazal form. The relatively steady meter and the use of the refrain produce an incantatory effect, which complements Sufi mystical themes well.[139]Among the masters of the form areRumi,the celebrated 13th-centuryPersianpoet,[140]Attar,12th century Iranian Sufi mystic poet who Rumi considered his master,[141]and their equally famous near-contemporaryHafez.Hafez uses the ghazal to expose hypocrisy and the pitfalls of worldliness, but also expertly exploits the form to express the divine depths and secular subtleties of love; creating translations that meaningfully capture such complexities of content and form is immensely challenging, but lauded attempts to do so in English includeGertrude Bell'sPoems from the Divan of Hafiz[142]andBeloved: 81 poems from Hafez(Bloodaxe Books) whose Preface addresses in detail the problematic nature of translating ghazals and whose versions (according toFatemeh Keshavarz,Roshan Institute forPersian Studies) preserve "that audacious and multilayered richness one finds in the originals".[143]Indeed, Hafez's ghazals have been the subject of much analysis, commentary and interpretation, influencing post-fourteenth century Persian writing more than any other author.[144][145]TheWest-östlicher DiwanofJohann Wolfgang von Goethe,a collection of lyrical poems, is inspired by the Persian poet Hafez.[146][147][148]

Genres

[edit]In addition to specific forms of poems, poetry is often thought of in terms of differentgenresand subgenres. A poetic genre is generally a tradition or classification of poetry based on the subject matter, style, or other broader literary characteristics.[149]Some commentators view genres as natural forms of literature. Others view the study of genres as the study of how different works relate and refer to other works.[150]

Narrative poetry

[edit]

Narrative poetry is a genre of poetry that tells astory.Broadly it subsumesepic poetry,but the term "narrative poetry" is often reserved for smaller works, generally with more appeal tohuman interest.Narrative poetry may be the oldest type of poetry. Many scholars ofHomerhave concluded that hisIliadandOdysseywere composed of compilations of shorter narrative poems that related individual episodes.

Much narrative poetry—such as Scottish and Englishballads,andBalticandSlavicheroic poems—isperformance poetrywith roots in a preliterateoral tradition.It has been speculated that some features that distinguish poetry from prose, such as meter,alliterationandkennings,once served asmemoryaids forbardswho recited traditional tales.[151]

Notable narrative poets have includedOvid,Dante,Juan Ruiz,William Langland,Chaucer,Fernando de Rojas,Luís de Camões,Shakespeare,Alexander Pope,Robert Burns,Adam Mickiewicz,Alexander Pushkin,Letitia Elizabeth Landon,Edgar Allan Poe,Alfred Tennyson,andAnne Carson.

Lyric poetry

[edit]

Lyric poetry is a genre that, unlikeepicand dramatic poetry, does not attempt to tell a story but instead is of a morepersonalnature. Poems in this genre tend to be shorter, melodic, and contemplative. Rather than depictingcharactersand actions, it portrays the poet's ownfeelings,states of mind,andperceptions.[152]Notable poets in this genre includeChristine de Pizan,John Donne,Charles Baudelaire,Gerard Manley Hopkins,Antonio Machado,andEdna St. Vincent Millay.

Epic poetry

[edit]

Epic poetry is a genre of poetry, and a major form ofnarrativeliterature. This genre is often defined as lengthy poems concerning events of a heroic or important nature to the culture of the time. It recounts, in a continuous narrative, the life and works of aheroicormythologicalperson or group of persons.[153]

Examples of epic poems areHomer'sIliadandOdyssey,Virgil'sAeneid,theNibelungenlied,Luís de Camões'Os Lusíadas,theCantar de Mio Cid,theEpic of Gilgamesh,theMahabharata,Lönnrot'sKalevala,Valmiki'sRamayana,Ferdowsi'sShahnama,Nizami(or Nezami)'s Khamse (Five Books), and theEpic of King Gesar.

While the composition of epic poetry, and oflong poemsgenerally, became less common in the west after the early 20th century, some notable epics have continued to be written.The CantosbyEzra Pound,Helen in EgyptbyH.D.,andPatersonbyWilliam Carlos Williamsare examples of modern epics.Derek Walcottwon aNobel prizein 1992 to a great extent on the basis of his epic,Omeros.[154]

Satirical poetry

[edit]

Poetry can be a powerful vehicle forsatire.TheRomanshad a strong tradition of satirical poetry, often written forpoliticalpurposes. A notable example is the Roman poetJuvenal'ssatires.[155]

The same is true of the English satirical tradition.John Dryden(aTory), the firstPoet Laureate,produced in 1682Mac Flecknoe,subtitled "A Satire on the True Blue Protestant Poet, T.S." (a reference toThomas Shadwell).[156]Satirical poets outside England includePoland'sIgnacy Krasicki,Azerbaijan'sSabir,Portugal'sManuel Maria Barbosa du Bocage,and Korea'sKim Kirim,especially noted for hisGisangdo.

Elegy

[edit]

An elegy is a mournful, melancholy or plaintive poem, especially alamentfor the dead or afuneralsong. The term "elegy," which originally denoted a type of poetic meter (elegiacmeter), commonly describes a poem ofmourning.An elegy may also reflect something that seems to the author to be strange or mysterious. The elegy, as a reflection on a death, on a sorrow more generally, or on something mysterious, may be classified as a form of lyric poetry.[157][158]

Notable practitioners of elegiac poetry have includedPropertius,Jorge Manrique,Jan Kochanowski,Chidiock Tichborne,Edmund Spenser,Ben Jonson,John Milton,Thomas Gray,Charlotte Smith,William Cullen Bryant,Percy Bysshe Shelley,Johann Wolfgang von Goethe,Evgeny Baratynsky,Alfred Tennyson,Walt Whitman,Antonio Machado,Juan Ramón Jiménez,William Butler Yeats,Rainer Maria Rilke,andVirginia Woolf.

Verse fable

[edit]

The fable is an ancientliterary genre,often (though not invariably) set inverse.It is a succinct story that featuresanthropomorphisedanimals,legendary creatures,plants,inanimate objects, or forces of nature that illustrate a moral lesson (a "moral"). Verse fables have used a variety ofmeterandrhymepatterns.[159]

Notable verse fabulists have includedAesop,Vishnu Sarma,Phaedrus,Marie de France,Robert Henryson,Biernat of Lublin,Jean de La Fontaine,Ignacy Krasicki,Félix María de Samaniego,Tomás de Iriarte,Ivan Krylov,andAmbrose Bierce.

Dramatic poetry

[edit]

Dramatic poetry isdramawritten inverseto be spoken or sung, and appears in varying, sometimes related forms in many cultures.Greek tragedyin verse dates to the 6th century B.C., and may have been an influence on the development of Sanskrit drama,[160]just as Indian drama in turn appears to have influenced the development of thebianwenverse dramas in China, forerunners ofChinese Opera.[161]East Asianverse dramas also include JapaneseNoh.Examples of dramatic poetry inPersian literatureincludeNizami's two famous dramatic works,Layla and MajnunandKhosrow and Shirin,Ferdowsi's tragedies such asRostam and Sohrab,Rumi'sMasnavi,Gorgani's tragedy ofVis and Ramin,andVahshi's tragedy ofFarhad.American poets of 20th century revive dramatic poetry, includingEzra Poundin "Sestina: Altaforte,"[162]T.S. Eliotwith "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock".[163][164]

Speculative poetry

[edit]

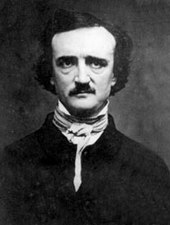

Speculative poetry, also known as fantastic poetry (of which weird or macabre poetry is a major sub-classification), is a poetic genre which deals thematically with subjects which are "beyond reality", whether viaextrapolationas inscience fictionor via weird and horrific themes as inhorror fiction.Such poetry appears regularly in modern science fiction and horror fiction magazines.

Edgar Allan Poeis sometimes seen as the "father of speculative poetry".[165]Poe's most remarkable achievement in the genre was his anticipation, by three-quarters of a century, of theBig Bang theoryof theuniverse's origin, in his then much-derided 1848essay(which, due to its very speculative nature, he termed a "prose poem"),Eureka: A Prose Poem.[166][167]

Prose poetry

[edit]

Prose poetry is a hybrid genre that shows attributes of both prose and poetry. It may be indistinguishable from themicro-story(a.k.a.the "short short story","flash fiction"). While some examples of earlier prose strike modern readers as poetic, prose poetry is commonly regarded as having originated in 19th-century France, where its practitioners includedAloysius Bertrand,Charles Baudelaire,Stéphane Mallarmé,andArthur Rimbaud.[168]

Since the late 1980s especially, prose poetry has gained increasing popularity, with entire journals, such asThe Prose Poem: An International Journal,[169]Contemporary Haibun Online,[170]andHaibun Today[171]devoted to that genre and its hybrids.Latin American poetsof the 20th century who wrote prose poems includeOctavio PazandAlejandra Pizarnik.

Light poetry

[edit]

Light poetry, orlight verse,is poetry that attempts to be humorous. Poems considered "light" are usually brief, and can be on a frivolous or serious subject, and often featureword play,includingpuns,adventurous rhyme and heavyalliteration.Although a few free verse poets have excelled at light verse outside the formal verse tradition, light verse in English usually obeys at least some formal conventions. Common forms include thelimerick,theclerihew,and thedouble dactyl.

While light poetry is sometimes condemned asdoggerel,or thought of as poetry composed casually, humor often makes a serious point in a subtle or subversive way. Many of the most renowned "serious" poets have also excelled at light verse. Notable writers of light poetry includeLewis Carroll,Ogden Nash,X. J. Kennedy,Willard R. Espy,Shel Silverstein,Gavin EwartandWendy Cope.

Slam poetry

[edit]

Slam poetry as a genre originated in 1986 inChicago,Illinois,whenMarc Kelly Smithorganized the first slam.[172][173]Slam performers comment emotively, aloud before an audience, on personal, social, or other matters. Slam focuses on the aesthetics of word play, intonation, and voice inflection. Slam poetry is often competitive, at dedicated "poetry slam"contests.[174]

Performance poetry

[edit]Performance poetry, similar to slam in that it occurs before an audience, is a genre of poetry that may fuse a variety of disciplines in a performance of a text, such asdance,music,and other aspects ofperformance art.[175][176]

Language happenings

[edit]The termhappeningwas popularized by theavant-gardemovements in the 1950s and regard spontaneous, site-specific performances.[177]Language happenings,termed from thepoeticscollectiveOBJECT:PARADISEin 2018, are events which focus less on poetry as a prescriptiveliterarygenre, but more as a descriptivelinguisticact and performance, often incorporating broader forms ofperformance artwhile poetry is read or created in that moment.[178][179]

See also

[edit]- Anti-poetry

- Digital poetry

- Glossary of poetry terms

- Improvisation

- List of poetry groups and movements

- Oral poetry

- Outline of poetry

- Persona poetry

- Phonestheme

- Phono-semantic matching

- Poetry reading

- Rhapsode

- Semantic differential

- Spoken word

Notes

[edit]- ^The word "verse" functions here as asynecdochewhich takes the poetic element of verse as representative of the entire art form. The word "verse" is often so used when contrasting the format of poetry with the format typical of most other writings:prose.

- ^In literary studies,linein western poetry is translated asbat.However, in some forms, the unit is more equivalent towak.To avoid confusion, this article will refer towakandbatinstead ofline,which may refer to either.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^"Poetry".Oxford Dictionaries.Oxford University Press. 2013. Archived fromthe originalon 18 June 2013.

poetry [...] Literary work in which the expression of feelings and ideas is given intensity by the use of distinctive style and rhythm; poems collectively or as a genre of literature.

- ^"Poetry".Merriam-Webster.2013.

poetry [...] 2: writing that formulates a concentrated imaginative awareness of experience in language chosen and arranged to create a specific emotional response through meaning, sound, and rhythm

- ^"Poetry".Dictionary.com.2013.

poetry [...] 1 the art of rhythmical composition, written or spoken, for exciting pleasure by beautiful, imaginative, or elevated thoughts.

- ^Ruth Finnegan,Oral Literature in Africa,Open Book Publishers, 2012.

- ^Strachan, John R.; Terry, Richard G. (2000).Poetry: an introduction.Edinburgh University Press. p. 119.ISBN978-0-8147-9797-6.

- ^Eliot, T. S. (1999) [1923]. "The Function of Criticism".Selected Essays.Faber & Faber. pp. 13–34.ISBN978-0-15-180387-3.

- ^Longenbach, James (1997).Modern Poetry After Modernism.Oxford University Press. p.9,103.ISBN978-0-19-510178-2.

- ^Schmidt, Michael, ed. (1999).The Harvill Book of Twentieth-Century Poetry in English.Harvill Press. pp.xxvii–xxxiii.ISBN978-1-86046-735-6.

- ^Höivik, Susan; Luger, Kurt (3 June 2009). "Folk Media for Biodiversity Conservation: A Pilot Project from the Himalaya-Hindu Kush".International Communication Gazette.71(4): 321–346.doi:10.1177/1748048509102184.ISSN1748-0485.S2CID143947520.

- ^Goody, Jack(1987).The Interface Between the Written and the Oral.Cambridge University Press. p.78.ISBN978-0-521-33794-6.

[...] poetry, tales, recitations of various kinds existed long before writing was introduced and these oral forms continued in modified 'oral' forms, even after the establishment of a written literature.

- ^abGoody, Jack (1987).The Interface Between the Written and the Oral.Cambridge University Press. p.98.ISBN978-0-521-33794-6.

- ^The Epic of Gilgamesh.Translated bySanders, N. K.(Revised ed.). Penguin Books. 1972. pp. 7–8.

- ^Mark, Joshua J. (13 August 2014)."The World's Oldest Love Poem".

'[...] What I held in my hand was one of the oldest love songs written down by the hand of man [...].'

- ^Arsu, Şebnem (14 February 2006)."Oldest Line in the World".The New York Times.Retrieved1 May2015.

A small tablet in a special display this month in the Istanbul Museum of the Ancient Orient is thought to be the oldest love poem ever found, the words of a lover from more than 4,000 years ago.

- ^Chyla, Julia; Rosińska-Balik, Karolina; Debowska-Ludwin, Joanna (2017).Current Research in Egyptology 17.Oxbow Books. pp. 159–161.ISBN978-1-78570-603-5.

- ^Ahl, Frederick; Roisman, Hanna M. (1996).The Odyssey Re-Formed.Cornell University Press. pp.1–26.ISBN978-0-8014-8335-6..

- ^Ebrey, Patricia(1993).Chinese Civilisation: A Sourcebook(2nd ed.). The Free Press. pp.11–13.ISBN978-0-02-908752-7.

- ^Cai, Zong-qi (July 1999)."In Quest of Harmony: Plato and Confucius on Poetry".Philosophy East and West.49(3): 317–345.doi:10.2307/1399898.JSTOR1399898.

- ^Abondolo, Daniel (2001).A poetics handbook: verbal art in the European tradition.Curzon. pp. 52–53.ISBN978-0-7007-1223-6.

- ^Gentz, Joachim (2008). "Ritual Meaning of Textual Form: Evidence from Early Commentaries of the Historiographic and Ritual Traditions". In Kern, Martin (ed.).Text and Ritual in Early China.University of Washington Press. pp. 124–148.ISBN978-0-295-98787-3.

- ^Habib, Rafey (2005).A history of literary criticism.John Wiley & Sons. pp.607–609, 620.ISBN978-0-631-23200-1.

- ^Jarrett A. Lobell (March–April 2022)."Poetic License".Archaeology Magazine.Archivedfrom the original on 7 December 2023.

- ^Alison Flood (8 September 2021)."'I don't care': text shows modern poetry began much earlier than believed ".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 18 January 2024.

- ^Tim Whitmarsh (August 2021)."Less Care, More Stress: A Rythmyic Poem From the Romas Empire".The Cambridge Classical Journal.67:135–163.doi:10.1017/S1750270521000051.S2CID242230189.

- ^Heath, Malcolm, ed. (1997).Aristotle'sPoetics.Penguin Books.ISBN978-0-14-044636-4.

- ^Frow, John (2007).Genre(Reprint ed.). Routledge. pp. 57–59.ISBN978-0-415-28063-1.

- ^Boggess, William F. (1968). "'Hermannus Alemannus' Latin Anthology of Arabic Poetry ".Journal of the American Oriental Society.88(4): 657–670.doi:10.2307/598112.JSTOR598112.Burnett, Charles (2001). "Learned Knowledge of Arabic Poetry, Rhymed Prose, and Didactic Verse from Petrus Alfonsi to Petrarch".Poetry and Philosophy in the Middle Ages: A Festschrift for Peter Dronke.Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 29–62.ISBN978-90-04-11964-2.

- ^Grendler, Paul F. (2004).The Universities of the Italian Renaissance.Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 239.ISBN978-0-8018-8055-1.

- ^Kant, Immanuel (1914).Critique of Judgment.Translated by Bernard, J. H. Macmillan. p. 131.Kant argues that the nature of poetry as a self-consciously abstract and beautiful form raises it to the highest level among the verbal arts, with tone or music following it, and only after that the more logical and narrative prose.

- ^Ou, Li (2009).Keats and negative capability.Continuum. pp. 1–3.ISBN978-1-4411-4724-0.

- ^Watten, Barrett (2003).The constructivist moment: from material text to cultural poetics.Wesleyan University Press. pp. 17–19.ISBN978-0-8195-6610-2.

- ^Abu-Mahfouz, Ahmad (2008)."Translation as a Blending of Cultures".Journal of Translation.4(1): 1–5.doi:10.54395/jot-x8fne.

- ^Highet, Gilbert (1985).The classical tradition: Greek and Roman influences on western literature(Reissued ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 355, 360, 479.ISBN978-0-19-500206-5.

- ^Wimsatt, William K. Jr.; Brooks, Cleanth (1957).Literary Criticism: A Short History.Vintage Books. p. 374.

- ^Johnson, Jeannine (2007).Why write poetry?: modern poets defending their art.Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 148.ISBN978-0-8386-4105-7.

- ^Jenkins, Lee M.; Davis, Alex, eds. (2007).The Cambridge companion to modernist poetry.Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–7, 38, 156.ISBN978-0-521-61815-1.

- ^Barthes, Roland(1978). "Death of the Author".Image-Music-Text.Farrar, Straus & Giroux. pp. 142–148.

- ^Connor, Steven (1997).Postmodernist culture: an introduction to theories of the contemporary(2nd ed.). Blackwell. pp. 123–28.ISBN978-0-631-20052-9.

- ^Preminger, Alex (1975).Princeton Encyclopaedia of Poetry and Poetics(enlarged ed.). London and Basingstoke: Macmillan Press. p. 919.ISBN978-1349156177.

- ^

Bloom, Harold(2010) [1986]. "Introduction". InBloom, Harold(ed.).Contemporary Poets.Bloom's modern critical views (revised ed.). New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 7.ISBN978-1604135886.Retrieved7 May2019.

The generation of poets who stand together now, mature and ready to write the major American verse of the twenty-first century, may yet be seen as what Stevens called 'a great shadow's last embellishment,' the shadow being Emerson's.

- ^Pinsky 1998,p. 52

- ^Fussell 1965,pp. 20–21

- ^Schülter, Julia (2005).Rhythmic Grammar.Walter de Gruyter. pp. 24, 304, 332.

- ^Yip, Moira(2002).Tone.Cambridge textbooks in linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–4, 130.ISBN978-0-521-77314-0.

- ^Fussell 1965,p. 12

- ^Jorgens, Elise Bickford (1982).The well-tun'd word: musical interpretations of English poetry, 1597–1651.University of Minnesota Press. p. 23.ISBN978-0-8166-1029-7.

- ^Fussell 1965,pp. 75–76

- ^Walker-Jones, Arthur (2003).Hebrew for biblical interpretation.Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 211–213.ISBN978-1-58983-086-8.

- ^Bala Sundara Raman, L.; Ishwar, S.; Kumar Ravindranath, Sanjeeth (2003). "Context Free Grammar for Natural Language Constructs: An implementation for Venpa Class of Tamil Poetry".Tamil Internet:128–136.CiteSeerX10.1.1.3.7738.

- ^Hartman, Charles O. (1980).Free Verse An Essay on Prosody.Northwestern University Press. pp. 24, 44, 47.ISBN978-0-8101-1316-9.

- ^Hollander 1981,p. 22

- ^McClure, Laura K. (2002),Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World: Readings and Sources,Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers, p. 38,ISBN978-0-631-22589-8

- ^Corn 1997,p. 24

- ^Corn 1997,pp. 25, 34

- ^abAnnis, William S. (January 2006)."Introduction to Greek Meter"(PDF).Aoidoi. pp. 1–15.

- ^"Examples of English metrical systems"(PDF).Fondazione Universitaria in provincia di Belluno. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 8 March 2012.Retrieved10 December2011.

- ^Fussell 1965,pp. 23–24

- ^"Portrait Bust".britishmuseum.org.The British Museum.

- ^Kiparsky, Paul (September 1975). "Stress, Syntax, and Meter".Language.51(3): 576–616.doi:10.2307/412889.JSTOR412889.

- ^Thompson, John (1961).The Founding of English Meter.Columbia University Press. p. 36.

- ^Pinsky 1998,pp. 11–24

- ^Pinsky 1998,p. 66

- ^Nabokov, Vladimir (1964).Notes on Prosody.Bollingen Foundation.pp.9–13.ISBN978-0-691-01760-0.

- ^Fussell 1965,pp. 36–71

- ^Nabokov, Vladimir (1964).Notes on Prosody.Bollingen Foundation. pp.46–47.ISBN978-0-691-01760-0.

- ^Adams 1997,p. 206

- ^Adams 1997,p. 63

- ^"What is Tetrameter?".tetrameter.com.Retrieved10 December2011.

- ^Adams 1997,p. 60

- ^James, E. D.; Jondorf, G. (1994).Racine: Phèdre.Cambridge University Press. pp.32–34.ISBN978-0-521-39721-6.

- ^Corn 1997,p. 65

- ^Osberg, Richard H. (2001). "'I kan nat geeste': Chaucer's Artful Alliteration ". In Gaylord, Alan T. (ed.).Essays on the art of Chaucer's Verse.Routledge. pp. 195–228.ISBN978-0-8153-2951-0.

- ^Alighieri, Dante (1994). "Introduction".The Inferno of Dante: A New Verse Translation.Translated by Pinsky, Robert. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.ISBN978-0-374-17674-7.

- ^abKiparsky, Paul (Summer 1973). "The Role of Linguistics in a Theory of Poetry".Daedalus.102(3): 231–44.

- ^Russom, Geoffrey(1998).Beowulf and old Germanic metre.Cambridge University Press. pp.64–86.ISBN978-0-521-59340-3.

- ^Liu, James J. Y. (1990).Art of Chinese Poetry.University of Chicago Press. pp. 21–22.ISBN978-0-226-48687-1.

- ^Wesling, Donald (1980).The chances of rhyme.University of California Press. pp. x–xi, 38–42.ISBN978-0-520-03861-5.

- ^Menocal, María Rosa(2003).The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History.University of Pennsylvania. p. 88.ISBN978-0-8122-1324-9.

- ^Sperl, Stefan, ed. (1996).Qasida poetry in Islamic Asia and Africa.Brill. p. 49.ISBN978-90-04-10387-0.

- ^Adams 1997,pp. 71–104

- ^Fussell 1965,p. 27

- ^Adams 1997,pp. 88–91

- ^Corn 1997,pp. 81–82, 85

- ^"FREE VERSE".25 May 2015.Retrieved22 May2021.

- ^"Forms of verse: Free verse [Victoria and Albert Museum]".4 July 2011.Retrieved22 May2021.

- ^Whitworth, Michael H. (2010).Reading modernist poetry.Wiley-Blackwell. p. 74.ISBN978-1-4051-6731-4.

- ^Hollander 1981,pp. 50–51

- ^Corn 1997,pp. 7–13

- ^Corn 1997,pp. 78–82

- ^Corn 1997,p. 78

- ^Dalrymple, Roger, ed. (2004).Middle English Literature: a guide to criticism.Blackwell Publishing. p. 10.ISBN978-0-631-23290-2.

- ^Corn 1997,pp. 78–79

- ^McTurk, Rory,ed. (2004).Companion to Old Norse-Icelandic Literature and Culture.Blackwell. pp. 269–280.ISBN978-1-4051-3738-6.

- ^Freedman, David Noel (July 1972). "Acrostics and Metrics in Hebrew Poetry".Harvard Theological Review.65(3): 367–392.doi:10.1017/s0017816000001620.S2CID162853305.

- ^Kampf, Robert (2010).Reading the Visual – 17th century poetry and visual culture.GRIN Verlag. pp. 4–6.ISBN978-3-640-60011-3.

- ^Bohn, Willard (1993).The aesthetics of visual poetry.University of Chicago Press. pp.1–8.ISBN978-0-226-06325-6.

- ^Sterling, Bruce (13 July 2009)."Web Semantics: Asemic writing".Wired.Archived fromthe originalon 27 October 2009.Retrieved10 December2011.

- ^Barfield, Owen (1987).Poetic diction: a study in meaning(2nd ed.). Wesleyan University Press. p. 41.ISBN978-0-8195-6026-1.

- ^Sheets, George A. (Spring 1981). "The Dialect Gloss, Hellenistic Poetics and Livius Andronicus".American Journal of Philology.102(1): 58–78.doi:10.2307/294154.JSTOR294154.

- ^Blank, Paula (1996).Broken English: dialects and the politics of language in Renaissance writings.Routledge. pp. 29–31.ISBN978-0-415-13779-9.

- ^Perloff, Marjorie(2002).21st-century modernism: the new poetics.Blackwell Publishers. p. 2.ISBN978-0-631-21970-5.

- ^Paden, William D., ed. (2000).Medieval lyric: genres in historical context.University of Illinois Press. p. 193.ISBN978-0-252-02536-5.

- ^The Poetics of Aristotle.Gutenberg. 1974. p. 22.

- ^Davis, Alex; Jenkins, Lee M., eds. (2007).The Cambridge companion to modernist poetry.Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–96.ISBN978-0-521-61815-1.

- ^San Juan, E. Jr. (2004).Working through the contradictions from cultural theory to critical practice.Bucknell University Press. pp. 124–125.ISBN978-0-8387-5570-9.

- ^Treip, Mindele Anne (1994).Allegorical poetics and the epic: the Renaissance tradition to Paradise Lost.University Press of Kentucky. p. 14.ISBN978-0-8131-1831-4.

- ^Crisp, P. (1 November 2005). "Allegory and symbol – a fundamental opposition?".Language and Literature.14(4): 323–338.doi:10.1177/0963947005051287.S2CID170517936.

- ^Gilbert, Richard (2004). "The Disjunctive Dragonfly".Modern Haiku.35(2): 21–44.

- ^Hollander 1981,pp. 37–46

- ^Fussell 1965,pp. 160–165

- ^Corn 1997,p. 94

- ^Minta, Stephen (1980).Petrarch and Petrarchism.Manchester University Press. pp.15–17.ISBN978-0-7190-0748-4.

- ^Quiller-Couch, Arthur, ed. (1900).Oxford Book of English Verse.Oxford University Press.

- ^Fussell 1965,pp. 119–133

- ^Watson, Burton(1971).Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century.(New York: Columbia University Press).ISBN0-231-03464-4,1

- ^Watson, Burton(1971).Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century.(New York: Columbia University Press).ISBN0-231-03464-4,1–2 and 15–18

- ^Watson, Burton(1971).Chinese Lyricism: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century.(New York: Columbia University Press).ISBN0-231-03464-4,111 and 115

- ^Faurot, Jeannette L (1998).Drinking with the moon.China Books & Periodicals. p.30.ISBN978-0-8351-2639-7.

- ^Wang, Yugen (1 June 2004). "Shige: The Popular Poetics of Regulated Verse".T'ang Studies.2004(22): 81–125.doi:10.1179/073750304788913221.S2CID163239068.

- ^Schirokauer, Conrad (1989).A brief history of Chinese and Japanese civilizations(2nd ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 119.ISBN978-0-15-505569-8.

- ^Kumin, Maxine(2002)."Gymnastics: The Villanelle".In Varnes, Kathrine (ed.).An Exaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of Their Art.University of Michigan Press. p.314.ISBN978-0-472-06725-1.

- ^"Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night"inThomas, Dylan (1952).In Country Sleep and Other Poems.New Directions Publications. p. 18.

- ^"Villanelle", inAuden, W. H. (1945).Collected Poems.Random House.

- ^"One Art", inBishop, Elizabeth (1976).Geography III.Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- ^Poets, Academy of American."Limerick | Academy of American Poets".poets.org.Retrieved10 October2020.

Limericks can be found in the work of Lord Alfred Tennyson, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson

- ^Samy Alim, H.; Ibrahim, Awad;Pennycook, Alastair,eds. (2009).Global linguistic flows.Taylor & Francis. p. 181.ISBN978-0-8058-6283-6.

- ^Brower, Robert H.; Miner, Earl (1988).Japanese court poetry.Stanford University Press. pp. 86–92.ISBN978-0-8047-1524-9.

- ^McCllintock, Michael; Ness, Pamela Miller; Kacian, Jim, eds. (2003).The tanka anthology: tanka in English from around the world.Red Moon Press. pp. xxx–xlviii.ISBN978-1-893959-40-8.

- ^Corn 1997,p. 117

- ^Ross, Bruce, ed. (1993).Haiku moment: an anthology of contemporary North American haiku.Charles E. Tuttle Co. p. xiii.ISBN978-0-8048-1820-9.

- ^Yanagibori, Etsuko."Basho's Haiku on the theme of Mt. Fuji".The personal notebook of Etsuko Yanagibori.Archived from the original on 28 May 2007.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ab"โคลง Khloong".Thai Language Audio Resource Center.Thammasat University.Retrieved6 March2012.Reproduced formHudak, Thomas John (1990).The indigenization of Pali meters in Thai poetry.Monographs in International Studies, Southeast Asia Series. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies.ISBN978-0-89680-159-2.

- ^Gray, Thomas (2000).English lyrics from Dryden to Burns.Elibron. pp. 155–56.ISBN978-1-4021-0064-2.

- ^Gayley, Charles Mills; Young, Clement C. (2005).English Poetry(Reprint ed.). Kessinger Publishing. p. lxxxv.ISBN978-1-4179-0086-2.

- ^Kuiper, Kathleen, ed. (2011).Poetry and drama literary terms and concepts.Britannica Educational Pub. in association with Rosen Educational Services. p.51.ISBN978-1-61530-539-1.

- ^"Ghazal - glossary on poets.org".Retrieved18 July2023.

- ^Campo, Juan E. (2009).Encyclopedia of Islam.Infobase. p. 260.ISBN978-0-8160-5454-1.

- ^Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt (Autumn 1990). "Musical Gesture and Extra-Musical Meaning: Words and Music in the Urdu Ghazal".Journal of the American Musicological Society.43(3): 457–497.doi:10.1525/jams.1990.43.3.03a00040.

- ^Sequeira, Isaac (1 June 1981). "The Mystique of the Mushaira".The Journal of Popular Culture.15(1): 1–8.doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1981.4745121.x.

- ^Schimmel, Annemarie(Spring 1988). "Mystical Poetry in Islam: The Case of Maulana Jalaladdin Rumi".Religion & Literature.20(1): 67–80.

- ^"Attar, the Sufi Poet and Master of Rumi, by Sholeh Wolpé".World Literature Today.Retrieved21 May2024.

- ^Hafez(1897).Poems from the Divan of Hafiz.Translated by Bell, Gertrude. London.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^"Beloved: 81 poems from Hafez".Bloodaxe Books. 2018.

- ^Yarshater. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^Hafiz and the Place of Iranian Culture in the WorldArchived3 May 2009 at theWayback MachinebyAga Khan III,9 November 1936 London.

- ^Shamel, Shafiq (2013).Goethe and Hafiz.Peter Lang.ISBN978-3-0343-0881-6.Retrieved29 October2014.

- ^"Goethe and Hafiz".Archived fromthe originalon 29 October 2014.Retrieved29 October2014.

- ^"GOETHE".Archived fromthe originalon 5 September 2015.Retrieved29 October2014.

- ^Chandler, Daniel."Introduction to Genre Theory".Aberystwyth University. Archived fromthe originalon 9 May 2015.Retrieved10 December2011.

- ^Schafer, Jorgen; Gendolla, Peter, eds. (2010).Beyond the screen: transformations of literary structures, interfaces and genres.Verlag. pp. 16, 391–402.ISBN978-3-8376-1258-5.

- ^Kirk, G. S. (2010).Homer and the Oral Tradition(reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–45.ISBN978-0-521-13671-6.

- ^Blasing, Mutlu Konuk(2006).Lyric poetry: the pain and the pleasure of words.Princeton University Press. pp. 1–22.ISBN978-0-691-12682-1.

- ^Hainsworth, J. B. (1989).Traditions of heroic and epic poetry.Modern Humanities Research Association. pp. 171–175.ISBN978-0-947623-19-7.

- ^"The Nobel Prize in Literature 1992: Derek Walcott".Swedish Academy.Retrieved10 December2011.

- ^Dominik, William J.; Wehrle, T. (1999).Roman verse satire: Lucilius to Juvenal.Bolchazy-Carducci. pp. 1–3.ISBN978-0-86516-442-0.

- ^Black, Joseph, ed. (2011).Broadview Anthology of British Literature.Vol. 1. Broadview Press. p. 1056.ISBN978-1-55481-048-2.

- ^Pigman, G. W. (1985).Grief and English Renaissance elegy.Cambridge University Press. pp.40–47.ISBN978-0-521-26871-4.

- ^Kennedy, David (2007).Elegy.Routledge. pp. 10–34.ISBN978-1-134-20906-4.

- ^Harpham, Geoffrey Galt; Abrams, M. H. (2011).A glossary of literary terms(10th ed.). Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 9.ISBN978-0-495-89802-3.

- ^Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1992).Sanskrit Drama in its origin, development, theory and practice.Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 57–58.ISBN978-81-208-0977-2.

- ^Dolby, William (1983). "Early Chinese Plays and Theatre". In Mackerras, Colin (ed.).Chinese Theater: From Its Origins to the Present Day.University of Hawaii Press. p.17.ISBN978-0-8248-1220-1.

- ^Giordano, Mathew (2004).Dramatic Poetics and American Poetic Culture, 1865–1904, Doctoral Dissertation.Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State.

Dramatic poetry: Pound's 'Sestina: Altaforte' or Eliot's 'The Love Song of J. Alfred Proufrock'.

- ^Eliot, T. S. (1951)."Poetry and Drama".tseliot.com.Retrieved9 October2020.

- ^"The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock | Modern American Poetry".www.modernamericanpoetry.org.Retrieved9 October2020.

- ^Allen, Mike (2005). Dutcher, Roger (ed.).The alchemy of stars.Science Fiction Poetry Association. pp. 11–17.ISBN978-0-8095-1162-4.

- ^Rombeck, Terry (22 January 2005)."Poe's little-known science book reprinted".Lawrence Journal-World & News.

- ^Robinson, Marilynne,"On Edgar Allan Poe",The New York Review of Books,vol. LXII, no. 2 (5 February 2015), pp. 4, 6.

- ^Monte, Steven (2000).Invisible fences: prose poetry as a genre in French and American literature.University of Nebraska Press. pp. 4–9.ISBN978-0-8032-3211-2.

- ^"The Prose Poem: An International Journal".Providence College.Retrieved10 December2011.

- ^"Contemporary Haibun Online".Retrieved10 December2011.

- ^"Haibun Today: A Haibun & Tanka Prose Journal".haibuntoday.com.

- ^"Honoring Marc Kelly Smith and International Poetry Slam Movement".Mary Hutchings Reed.Retrieved5 May2019.

- ^"A Brief Guide to Slam Poetry".Academy of American Poets.Retrieved5 May2019.

- ^"5 Tips on Spoken Word".Power Poetry.Retrieved5 May2019.

- ^Wheeler, Lesley(2008).Voicing American Poetry: Sound and Performance from the 1920s to the Present.Cornell University Press.ISBN978-0801446689.

- ^Seavon, Fernanda (March 2022)."Instantní Nostalgie".A2(5/2022): 11.

- ^Bigsby, Christopher W.(1985).A Critical Introduction to Twentieth-Century American Drama: Volume 3 Beyond Broadway.Cambridge University Press. p. 45.ISBN978-0521278966.Retrieved5 September2012.

- ^Gironès, Cristina (16 February 2022)."Object Paradise, el colectivo artístico que quiere devolver la vida y la voz al barrio de Žižkov".Radio Prague International.Retrieved21 March2022.

- ^"obtydeník živé literatury".Tvar(7). July 2022.Retrieved2 June2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adams, Stephen J. (1997).Poetic designs: an introduction to meters, verse forms and figures of speech.Broadview.ISBN978-1-55111-129-2.

- Corn, Alfred (1997).The Poem's Heartbeat: A Manual of Prosody.Storyline Press.ISBN978-1-885266-40-8.

- Fussell, Paul(1965).Poetic Meter and Poetic Form.Random House.

- Hollander, John(1981).Rhyme's Reason.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-02740-2.

- Pinsky, Robert(1998).The Sounds of Poetry.Farrar, Straus and Giroux.ISBN978-0-374-26695-0.

- Speyer, Leonora(1926).Fiddler's farewell.New York: Alred A. Knopf.

Further reading

[edit]- Encyclopedias

- Greene, Roland;et al., eds. (2012).The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics(4th rev. ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.ISBN978-0-691-15491-6.

- Other critics

- Brooks, Cleanth(1947).The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry.Harcourt Brace & Company.ISBN978-0156957052.

- Finch, Annie(2011).A Poet's Ear: A Handbook of Meter and Form.University of Michigan Press.ISBN978-0-472-05066-6.

- Fry, Stephen(2007).The Ode Less Travelled: Unlocking the Poet Within.Arrow Books.ISBN978-0-09-950934-9.

- Gosse, Edmund William(1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 27 (11th ed.). pp. 1041–1047.

- Pound, Ezra(1951).ABC of Reading.Faber.