Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

Apolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon(PAH) is a class oforganic compoundsthat is composed of multiplearomatic rings.The simplest representative isnaphthalene,having two aromatic rings, and the three-ring compoundsanthraceneandphenanthrene.PAHs are uncharged, non-polar and planar. Many are colorless. Many of them are found incoaland inoildeposits, and are also produced by the incomplete combustion oforganic matter—for example, in engines and incinerators or when biomass burns inforest fires.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are discussed as possiblestarting materialsforabioticsyntheses ofmaterialsrequired by theearliest forms of life.[1][2]

Nomenclature and structure

[edit]The termspolyaromatic hydrocarbon,[3]orpolynuclear aromatic hydrocarbon[4](abbreviated as PNA) are also used for this concept.[5]

By definition, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons have multiple aromatic rings, precludingbenzenefrom being considered a PAH. Some sources, such as theUS EPAandCDC,considernaphthaleneto be the simplest PAH.[6]Other authors consider PAHs to start with the tricyclic speciesphenanthreneandanthracene.[7]Most authors exclude compounds that includeheteroatomsin the rings, or carrysubstituents.[8]

A polyaromatic hydrocarbon may have rings of various sizes, including some that are not aromatic. Those that have only six-membered rings are said to bealternant.[9]

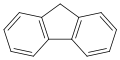

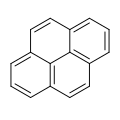

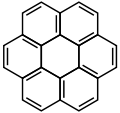

The following are examples of PAHs that vary in the number and arrangement of their rings:

- Examples of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

Geometry

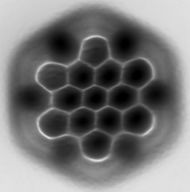

[edit]Most PAHs, like naphthalene, anthracene, and coronene, are planar. This geometry is a consequence of the fact that theσ-bondsthat result from the merger of sp2hybrid orbitalsof adjacent carbons lie on the same plane as the carbon atom. Those compounds areachiral,since the plane of the molecule is a symmetry plane.

In rare cases, PAHs are not planar. In some cases, the non-planarity may be forced by thetopologyof the molecule and the stiffness (in length and angle) of the carbon-carbon bonds. For example, unlikecoronene,corannuleneadopts a bowl shape in order to reduce the bond stress. The two possible configurations, concave and convex, are separated by a relatively low energy barrier (about 11kcal/mol).[10]

In theory, there are 51 structural isomers of coronene that have six fused benzene rings in a cyclic sequence, with two edge carbons shared between successive rings. All of them must be non-planar and have considerable higher bonding energy (computed to be at least 130 kcal/mol) than coronene; and, as of 2002, none of them had been synthesized.[11]

Other PAHs that might seem to be planar, considering only the carbon skeleton, may be distorted by repulsion or steric hindrance between thehydrogenatoms in their periphery. Benzo[c]phenantrene, with four rings fused in a "C" shape, has a slight helical distortion due to repulsion between the closest pair of hydrogen atoms in the two extremal rings.[12]This effect also causes distortion of picene.[13]

Adding another benzene ring to form dibenzo[c,g]phenantrene createssteric hindrancebetween the two extreme hydrogen atoms.[14]Adding two more rings on the same sense yieldsheptahelicenein which the two extreme rings overlap.[15]These non-planar forms are chiral, and theirenantiomerscan be isolated.[16]

Benzenoid hydrocarbons

[edit]Thebenzenoid hydrocarbonshave been defined as condensed polycyclic unsaturated fully-conjugated hydrocarbons whose molecules are essentially planar with all rings six-membered. Full conjugation means that all carbon atoms and carbon-carbon bonds must have the sp2structure of benzene. This class is largely a subset of the alternant PAHs, but is considered to include unstable or hypothetical compounds liketrianguleneorheptacene.[16]

As of 2012, over 300 benzenoid hydrocarbons had been isolated and characterized.[16]

Bonding and aromaticity

[edit]Thearomaticityvaries for PAHs. According toClar's rule,[17]theresonance structureof a PAH that has the largest number of disjoint aromaticpi sextets—i.e.benzene-like moieties—is the most important for the characterization of the properties of that PAH.[18]

- Benzene-substructure resonance analysis for Clar's rule

-

Phenanthrene

-

Anthracene

-

Chrysene

For example,phenanthrenehas two Clar structures: one with just one aromatic sextet (the middle ring), and the other with two (the first and third rings). The latter case is therefore the more characteristic electronic nature of the two. Therefore, in this molecule the outer rings have greater aromatic character whereas the central ring is less aromatic and therefore more reactive.[citation needed]In contrast, inanthracenethe resonance structures have one sextet each, which can be at any of the three rings, and the aromaticity spreads out more evenly across the whole molecule.[citation needed]This difference in number of sextets is reflected in the differingultraviolet–visible spectraof these two isomers, as higher Clar pi-sextets are associated with largerHOMO-LUMOgaps;[19]the highest-wavelength absorbance of phenanthrene is at 293 nm, while anthracene is at 374 nm.[20]Three Clar structures with two sextets each are present in the four-ringchrysenestructure: one having sextets in the first and third rings, one in the second and fourth rings, and one in the first and fourth rings.[citation needed]Superposition of these structures reveals that the aromaticity in the outer rings is greater (each has a sextet in two of the three Clar structures) compared to the inner rings (each has a sextet in only one of the three).

Properties

[edit]Physicochemical

[edit]PAHs arenonpolarandlipophilic.Larger PAHs are generallyinsolublein water, although some smaller PAHs are soluble.[21][22]The larger members are also poorly soluble inorganic solventsand inlipids.The larger members, e.g. perylene, are strongly colored.[16]

Redox

[edit]Polycyclic aromatic compounds characteristically yieldradicalsandanionsupon treatment with alkali metals. The large PAH form dianions as well.[23]Theredox potentialcorrelates with the size of the PAH.

Half-cellpotential of aromatic compounds against theSCE(Fc+/0)[24] Compound Potential (V) benzene −3.42 biphenyl[25] −2.60 (-3.18) naphthalene −2.51 (-3.1) anthracene −1.96 (-2.5) phenanthrene −2.46 perylene −1.67 (-2.2) pentacene −1.35

Sources

[edit]Artificial

[edit]The dominant sources of PAHs in the environment are from human activity: wood-burning and combustion of otherbiofuelssuch as dung or crop residues contribute more than half of annual global PAH emissions, particularly due to biofuel use in India and China.[26][27]As of 2004, industrial processes and the extraction and use offossil fuelsmade up slightly more than one quarter of global PAH emissions, dominating outputs in industrial countries such as the United States.[26]

A year-long sampling campaign in Athens, Greece found a third (31%) of PAH urbanair pollutionto be caused by wood-burning, like diesel and oil (33%) and gasoline (29%). It also found that wood-burning is responsible for nearly half (43%) of annual PAH cancer-risk (carcinogenicpotential) compared to the other sources and that wintertime PAH levels were 7 times higher than in other seasons, especially if atmospheric dispersion is low.[28][29]

Lower-temperature combustion, such astobacco smokingorwood-burning,tends to generate low molecular weight PAHs, whereas high-temperature industrial processes typically generate PAHs with higher molecular weights.[30]Incense is also a source.[31]

PAHs are typically found as complex mixtures.[32][30]

Natural

[edit]Natural fires

[edit]PAHs may result from the incompletecombustionoforganic matterin naturalwildfires.[27][26]Substantially higher outdoor air, soil, and water concentrations of PAHs have been measured in Asia, Africa, and Latin America than in Europe, Australia, the U.S., and Canada.[26]

Fossil carbon

[edit]Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are primarily found in natural sources such asbitumen.[33][34]

PAHs can also be produced geologically when organic sediments are chemically transformed intofossil fuelssuch as oil andcoal.[32]The rare mineralsidrialite,curtisite,andcarpathiteconsist almost entirely of PAHs that originated from such sediments, that were extracted, processed, separated, and deposited by very hot fluids.[35][13][36] High levels of such PAHs have been detected in theCretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary,more than 100 times the level in adjacent layers. The spike was attributed to massive fires that consumed about 20% of the terrestrial above-ground biomass in a very short time.[37]

Extraterrestrial

[edit]PAHs are prevalent in theinterstellar medium(ISM) of galaxies in both the nearby and distant Universe and make up a dominant emission mechanism in the mid-infrared wavelength range, containing as much as 10% of the total integrated infrared luminosity of galaxies.[38]PAHs generally trace regions of cold molecular gas, which are optimum environments for the formation of stars.[38]

NASA'sSpitzer Space TelescopeandJames Webb Space Telescopeinclude instruments for obtaining both images and spectra of light emitted by PAHs associated withstar formation.These images can trace the surface of star-formingcloudsin our own galaxy or identify star forming galaxies in the distant universe.[39]In June 2013, PAHs were detected in theupper atmosphereofTitan,the largestmoonof theplanetSaturn.[40]

Minor sources

[edit]Volcanic eruptionsmay emit PAHs.[32]

Certain PAHs such asperylenecan also be generated inanaerobicsediments from existing organic material, although it remains undetermined whether abiotic or microbial processes drive their production.[41][42][43]

Distribution in the environment

[edit]Aquatic environments

[edit]Most PAHs are insoluble in water, which limits their mobility in the environment, although PAHssorbto fine-grained organic-richsediments.[44][45][46][47]Aqueous solubility of PAHs decreases approximatelylogarithmicallyasmolecular massincreases.[48]

Two-ringed PAHs, and to a lesser extent three-ringed PAHs, dissolve in water, making them more available for biological uptake anddegradation.[47][48][49]Further, two- to four-ringed PAHsvolatilizesufficiently to appear in the atmosphere predominantly in gaseous form, although the physical state of four-ring PAHs can depend on temperature.[50][51]In contrast, compounds with five or more rings have low solubility in water and low volatility; they are therefore predominantly in solidstate,bound toparticulateair pollution,soils,orsediments.[47]In solid state, these compounds are less accessible for biological uptake or degradation, increasing their persistence in the environment.[48][52]

Human exposure

[edit]Human exposure varies across the globe and depends on factors such as smoking rates, fuel types in cooking, and pollution controls on power plants, industrial processes, and vehicles.[32][26][53]Developed countries with stricter air and water pollution controls, cleaner sources of cooking (i.e., gas and electricity vs. coal or biofuels), and prohibitions of public smoking tend to have lower levels of PAH exposure, while developing and undeveloped countries tend to have higher levels.[32][26][53] Surgical smoke plumes have been proven to contain PAHs in several independent research studies.[54]

Burning solid fuels such ascoalandbiofuelsin the home for cooking and heating is a dominant global source of PAH emissions that in developing countries leads to high levels of exposure toindoor particulate air pollutioncontaining PAHs, particularly for women and children who spend more time in the home or cooking.[26][55]

In industrial countries, people who smoke tobacco products, or who are exposed tosecond-hand smoke,are among the most highly exposed groups;tobacco smokecontributes to 90% of indoor PAH levels in the homes of smokers.[53]For the general population in developed countries, the diet is otherwise the dominant source of PAH exposure, particularly from smoking or grilling meat or consuming PAHs deposited on plant foods, especially broad-leafed vegetables, during growth.[56]Exposure also occurs through drinking alcohol aged in charred barrels, flavored with peat smoke, or made with roasted grains.[57]PAHs are typically at low concentrations in drinking water.[53]

Emissions from vehicles such as cars and trucks can be a substantial outdoor source of PAHs in particulate air pollution.[32][26]Geographically, major roadways are thus sources of PAHs, which may distribute in the atmosphere or deposit nearby.[58]Catalytic convertersare estimated to reduce PAH emissions from gasoline-fired vehicles by 25-fold.[32]

People can also be occupationally exposed during work that involves fossil fuels or their derivatives, wood-burning,carbon electrodes,or exposure todiesel exhaust.[59][60]Industrial activity that can produce and distribute PAHs includesaluminum,iron,andsteelmanufacturing;coal gasification,tardistillation,shale oil extraction;production ofcoke,creosote,carbon black,andcalcium carbide;road paving andasphaltmanufacturing;rubbertireproduction; manufacturing or use ofmetal workingfluids; and activity of coal ornatural gaspower stations.[32][59][60]

Environmental pollution and degradation

[edit]

PAHs typically disperse fromurbanandsuburbannon-point sourcesthrough roadrunoff,sewage,andatmospheric circulationand subsequent deposition of particulate air pollution.[61][62]Soiland riversedimentnear industrial sites such as creosote manufacturing facilities can be highly contaminated with PAHs.[32]Oil spills,creosote,coal miningdust, and other fossil fuel sources can also distribute PAHs in the environment.[32][63]

Two- and three-ringed PAHs can disperse widely while dissolved in water or as gases in the atmosphere, while PAHs with higher molecular weights can disperse locally or regionally adhered to particulate matter that is suspended in air or water until the particles land or settle out of thewater column.[32]PAHs have a strong affinity fororganic carbon,and thus highly organic sediments inrivers,lakes,and theoceancan be a substantial sink for PAHs.[58]

Algaeand someinvertebratessuch asprotozoans,mollusks,and manypolychaeteshave limited ability tometabolizePAHs andbioaccumulatedisproportionate concentrations of PAHs in their tissues; however, PAH metabolism can vary substantially across invertebrate species.[62][64]Mostvertebratesmetabolize and excrete PAHs relatively rapidly.[62]Tissue concentrations of PAHs do not increase (biomagnify) from the lowest to highest levels of food chains.[62]

PAHs transform slowly to a wide range of degradation products. Biological degradation bymicrobesis a dominant form of PAH transformation in the environment.[52][65]Soil-consuming invertebratessuch asearthwormsspeed PAH degradation, either through direct metabolism or by improving the conditions for microbial transformations.[65]Abiotic degradation in the atmosphere and the top layers of surface waters can produce nitrogenated, halogenated, hydroxylated, and oxygenated PAHs; some of these compounds can be more toxic, water-soluble, and mobile than their parent PAHs.[62][66][67]

Urban soils

[edit]TheBritish Geological Surveyreported the amount and distribution of PAH compounds including parent and alkylated forms in urban soils at 76 locations inGreater London.[68]The study showed that parent (16 PAH) content ranged from 4 to 67 mg/kg (dry soil weight) and an average PAH concentration of 18 mg/kg (dry soil weight) whereas the total PAH content (33 PAH) ranged from 6 to 88 mg/kg andfluorantheneandpyrenewere generally the most abundant PAHs.[68]Benzo[a]pyrene(BaP), the most toxic of the parent PAHs, is widely considered a key marker PAH for environmental assessments;[69]the normal background concentration of BaP in the London urban sites was 6.9 mg/kg (dry soil weight).[68]Londonsoils contained more stable four- to six-ringed PAHs which were indicative of combustion and pyrolytic sources, such as coal and oil burning and traffic-sourced particulates. However, the overall distribution also suggested that the PAHs in London soils had undergone weathering and been modified by a variety of pre-and post-depositional processes such as volatilization and microbialbiodegradation.

Peatlands

[edit]Managedburningofmoorlandvegetation in the UK has been shown to generate PAHs which become incorporated into thepeatsurface.[70]Burning of moorland vegetation such asheatherinitially generates high amounts of two- and three-ringed PAHs relative to four- to six-ringed PAHs in surface sediments, however, this pattern is reversed as the lowermolecular weightPAHs are attenuated by biotic decay andphotodegradation.[70]Evaluation of the PAH distributions using statistical methods such as principal component analyses (PCA) enabled the study to link the source (burnt moorland) to pathway (suspended stream sediment) to the depositional sink (reservoir bed).[70]

Rivers, estuarine and coastal sediments

[edit]Concentrations of PAHs in river and estuarinesedimentsvary according to a variety of factors including proximity to municipal and industrial discharge points, wind direction and distance from major urban roadways, as well as tidal regime which controls the diluting effect of generally cleaner marine sediments relative to freshwater discharge.[61][71][72]Consequently, the concentrations ofpollutantsin estuaries tends to decrease at the river mouth.[73]Understanding of sediment hosted PAHs in estuaries is important for the protection of commercialfisheries(such asmussels) and general environmental habitat conservation because PAHs can impact the health of suspension and sediment feeding organism.[74]River-estuary surface sediments in the UK tend to have a lower PAH content than sediments buried 10–60 cm from the surface reflecting lower present day industrial activity combined with improvement in environmental legislation of PAH.[72]Typical PAH concentrations in UK estuaries range from about 19 to 16,163 µg/kg (dry sediment weight) in theRiver Clydeand 626 to 3,766 µg/kg in theRiver Mersey.[72][75]In general estuarine sediments with a higher naturaltotal organic carboncontent (TOC) tend to accumulate PAHs due to highsorptioncapacity of organic matter.[75]A similar correspondence between PAHs and TOC has also been observed in the sediments of tropicalmangroveslocated on the coast of southern China.[76]

Human health

[edit]Canceris a primary human health risk of exposure to PAHs.[77]Exposure to PAHs has also been linked with cardiovascular disease and poor fetal development.

Cancer

[edit]PAHs have been linked toskin,lung,bladder,liver,andstomachcancers in well-established animal model studies.[77]Specific compounds classified by various agencies as possible or probable human carcinogens are identified in the section "Regulation and Oversight"below.

History

[edit]

Historically, PAHs contributed substantially to our understanding of adverse health effects from exposures toenvironmental contaminants,including chemicalcarcinogenesis.[78]In 1775,Percivall Pott,a surgeon atSt. Bartholomew's Hospitalin London, observed thatscrotal cancerwas unusually common in chimney sweepers and proposed the cause as occupational exposure tosoot.[79]A century later,Richard von Volkmannreported increased skin cancers in workers of thecoal tarindustry of Germany, and by the early 1900s increased rates of cancer from exposure to soot and coal tar was widely accepted. In 1915,YamigawaandIchicawawere the first to experimentally produce cancers, specifically of the skin, by topically applying coal tar to rabbit ears.[79]

In 1922,Ernest Kennawaydetermined that the carcinogenic component of coal tar mixtures was an organic compound consisting of only carbon and hydrogen. This component was later linked to a characteristicfluorescentpattern that was similar but not identical tobenz[a]anthracene,a PAH that was subsequently demonstrated to causetumors.[79]Cook, Hewett andHiegerthen linked the specific spectroscopic fluorescent profile ofbenzo[a]pyreneto that of the carcinogenic component of coal tar,[79]the first time that a specific compound from an environmental mixture (coal tar) was demonstrated to be carcinogenic.

In the 1930s and later, epidemiologists from Japan, the UK, and the US, includingRichard Dolland various others, reported greater rates of death fromlung cancerfollowing occupational exposure to PAH-rich environments among workers incoke ovensandcoal carbonizationandgasificationprocesses.[80]

Mechanisms of carcinogenesis

[edit]

The structure of a PAH influences whether and how the individual compound is carcinogenic.[77][81]Some carcinogenic PAHs aregenotoxicand inducemutationsthat initiate cancer; others are not genotoxic and instead affect cancer promotion or progression.[81][82]

PAHs that affectcancer initiationare typically first chemically modified byenzymesinto metabolites that react with DNA, leading to mutations. When the DNA sequence is altered in genes that regulatecell replication,cancer can result. Mutagenic PAHs, such as benzo[a]pyrene, usually have four or more aromatic rings as well as a "bay region", a structural pocket that increases reactivity of the molecule to the metabolizing enzymes.[83]Mutagenic metabolites of PAHs includediolepoxides,quinones,andradicalPAHcations.[83][84][85]These metabolites can bind to DNA at specific sites, forming bulky complexes calledDNA adductsthat can be stable or unstable.[79][86]Stable adducts may lead toDNA replicationerrors, while unstable adducts react with the DNA strand, removing apurinebase (eitheradenineorguanine).[86]Such mutations, if they are not repaired, can transform genes encoding for normalcell signalingproteins into cancer-causingoncogenes.[81]Quinones can also repeatedly generatereactive oxygen speciesthat may independently damage DNA.[83]

Enzymes in thecytochromefamily (CYP1A1,CYP1A2,CYP1B1) metabolize PAHs to diol epoxides.[87]PAH exposure can increase production of the cytochrome enzymes, allowing the enzymes to convert PAHs into mutagenic diol epoxides at greater rates.[87]In this pathway, PAH molecules bind to thearyl hydrocarbon receptor(AhR) and activate it as atranscription factorthat increases production of the cytochrome enzymes. The activity of these enzymes may at times conversely protect against PAH toxicity, which is not yet well understood.[87]

Low molecular weight PAHs, with two to four aromatic hydrocarbon rings, are more potent asco-carcinogensduring the promotional stage of cancer. In this stage, an initiated cell (a cell that has retained a carcinogenic mutation in a key gene related to cell replication) is removed from growth-suppressing signals from its neighboring cells and begins to clonally replicate.[88]Low-molecular-weight PAHs that have bay or bay-like regions can dysregulategap junctionchannels, interfering with intercellular communication, and also affectmitogen-activated protein kinasesthat activate transcription factors involved in cell proliferation.[88]Closure of gap junction protein channels is a normal precursor to cell division. Excessive closure of these channels after exposure to PAHs results in removing a cell from the normal growth-regulating signals imposed by its local community of cells, thus allowing initiated cancerous cells to replicate. These PAHs do not need to be enzymatically metabolized first. Low molecular weight PAHs are prevalent in the environment, thus posing a significant risk to human health at the promotional phases of cancer.

Cardiovascular disease

[edit]Adult exposure to PAHs has been linked tocardiovascular disease.[89]PAHs are among the complex suite of contaminants intobacco smokeandparticulate air pollutionand may contribute to cardiovascular disease resulting from such exposures.[90]

In laboratory experiments, animals exposed to certain PAHs have shown increased development of plaques (atherogenesis) within arteries.[91]Potential mechanisms for thepathogenesisand development of atherosclerotic plaques may be similar to the mechanisms involved in the carcinogenic and mutagenic properties of PAHs.[91]A leading hypothesis is that PAHs may activate the cytochrome enzymeCYP1B1invascular smooth musclecells. This enzyme then metabolically processes the PAHs to quinone metabolites that bind to DNA in reactive adducts that remove purine bases. The resulting mutations may contribute to unregulated growth of vascular smooth muscle cells or to their migration to the inside of the artery, which are steps inplaqueformation.[90][91]These quinone metabolites also generatereactive oxygen speciesthat may alter the activity of genes that affect plaque formation.[91]

Oxidative stressfollowing PAH exposure could also result in cardiovascular disease by causinginflammation,which has been recognized as an important factor in the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease.[92][93]Biomarkersof exposure to PAHs in humans have been associated with inflammatory biomarkers that are recognized as important predictors of cardiovascular disease, suggesting that oxidative stress resulting from exposure to PAHs may be a mechanism of cardiovascular disease in humans.[94]

Developmental impacts

[edit]Multipleepidemiologicalstudies of people living in Europe, the United States, and China have linkedin uteroexposure to PAHs, through air pollution or parental occupational exposure, with poor fetal growth, reduced immune function, and poorerneurologicaldevelopment, including lowerIQ.[95][96][97][98]

Regulation and oversight

[edit]Some governmental bodies, including theEuropean Unionas well asNIOSHand theUnited States Environmental Protection Agency(EPA), regulate concentrations of PAHs in air, water, and soil.[99]TheEuropean Commissionhas restricted concentrations of 8 carcinogenic PAHs in consumer products that contact the skin or mouth.[100]

Priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons identified by the US EPA, the USAgency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry(ATSDR), and theEuropean Food Safety Authority(EFSA) due to their carcinogenicity or genotoxicity and/or ability to be monitored are the following:[101][102][103]

|

|

- AConsidered probable or possible human carcinogens by the US EPA, the European Union, and/or theInternational Agency for Research on Cancer(IARC).[103][5]

Detection and optical properties

[edit]A spectral database exists[1]for tracking polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in theuniverse.[104]Detection of PAHs in materials is often done usinggas chromatography-mass spectrometryorliquid chromatographywithultraviolet-visibleorfluorescencespectroscopic methods or by using rapid test PAH indicator strips. Structures of PAHs have been analyzed using infrared spectroscopy.[105]

PAHs possess very characteristicUV absorbance spectra.These often possess many absorbance bands and are unique for each ring structure. Thus, for a set ofisomers,each isomer has a different UV absorbance spectrum than the others. This is particularly useful in the identification of PAHs. Most PAHs are alsofluorescent,emitting characteristic wavelengths of light when they are excited (when the molecules absorb light). The extended pi-electron electronic structures of PAHs lead to these spectra, as well as to certain large PAHs also exhibitingsemi-conductingand other behaviors.

Origins of life

[edit]

Green areas show regions where radiation from hot stars collided with large molecules and small dust grains called "polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons" (PAHs), causing them tofluoresce.

(Spitzer Space Telescope,2018)

PAHs may be abundant in the universe.[2][106][107][108]They seem to have been formed as early as a couple of billion years after theBig Bang,and are associated withnew starsandexoplanets.[1]More than 20% of thecarbonin the universe may be associated with PAHs.[1]PAHs are considered possiblestarting materialfor theearliest forms of life.[1][2] Light emitted by theRed Rectangle nebulapossesses spectral signatures that suggest the presence ofanthraceneandpyrene.[109][110]This report was considered a controversial hypothesis that as nebulae of the same type as the Red Rectangle approach the ends of their lives, convection currents cause carbon and hydrogen in the nebulae's cores to get caught in stellar winds, and radiate outward. As they cool, the atoms supposedly bond to each other in various ways and eventually form particles of a million or more atoms. Adolf Witt and his team inferred[109]that PAHs—which may have been vital in the formation ofearly life on Earth—can only originate in nebulae.[110]

PAHs, subjected tointerstellar medium (ISM)conditions, are transformed, throughhydrogenation,oxygenation,andhydroxylation,to more complexorganic compounds— "a step along the path towardamino acidsandnucleotides,the raw materials ofproteinsandDNA,respectively ".[112][113]Further, as a result of these transformations, the PAHs lose theirspectroscopic signaturewhich could be one of the reasons "for the lack of PAH detection ininterstellar icegrains,particularly the outer regions of cold, dense clouds or the upper molecular layers ofprotoplanetary disks."[112][113]

Low-temperature chemical pathways from simpleorganic compoundsto complex PAHs are of interest. Such chemical pathways may help explain the presence of PAHs in the low-temperature atmosphere ofSaturn's moonTitan,and may be significant pathways, in terms of thePAH world hypothesis,in producing precursors to biochemicals related to life as we know it.[114][115]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abcdeHoover, R. (2014-02-21)."Need to Track Organic Nano-Particles Across the Universe? NASA's Got an App for That".NASA.Retrieved2014-02-22.

- ^abcAllamandola, Louis; et al. (2011-04-13)."Cosmic Distribution of Chemical Complexity".NASA.Archived fromthe originalon 2014-02-27.Retrieved2014-03-03.

- ^Gerald Rhodes, Richard B. Opsal, Jon T. Meek, and James P. Reilly (1983): "Analysis of polyaromatic hydrocarbon mixtures with laser ionization gas chromatography/mass spectrometry".Analytic Chemistry,volume 55, issue 2, pages 280–286doi:10.1021/ac00253a023

- ^Kevin C. Jones, Jennifer A. Stratford, Keith S. Waterhouse, et al. (1989): "Increases in the polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbon content of an agricultural soil over the last century".Environmental Science and Technology,volume 23, issue 1, pages 95–101.doi:10.1021/es00178a012

- ^abGehle, Kim."Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): Health Effects Associated With PAH Exposure".CDC.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.Archivedfrom the original on 6 August 2019.Retrieved2016-02-01.

- ^"Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)"(PDF).

Naphthalene is a PAH that is produced commercially in the US

- ^G.P. Moss IUPAC nomenclature for fused-ring systems[full citation needed]

- ^Fetzer, John C. (16 April 2007). "The chemistry and analysis of large PAHs".Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds.27(2): 143–162.doi:10.1080/10406630701268255.S2CID97930473.

- ^Harvey, R. G. (1998). "Environmental Chemistry of PAHs".PAHs and Related Compounds: Chemistry.The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Springer. pp. 1–54.ISBN978-3-540-49697-7.

- ^Marina V. Zhigalko, Oleg V. Shishkin, Leonid Gorb, and Jerzy Leszczynski (2004): "Out-of-plane deformability of aromatic systems in naphthalene, anthracene and phenanthrene".Journal of Molecular Structure,volume 693, issues 1–3, pages 153-159.doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2004.02.027

- ^Jan Cz. Dobrowolski (2002): "On the belt and Moebius isomers of the coronene molecule".Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Science,volume 42, issue 3, pages 490–499doi:10.1021/ci0100853

- ^F. H. Herbstein and G. M. J. Schmidt (1954): "The structure of overcrowded aromatic compounds. Part III. The crystal structure of 3:4-benzophenanthrene".Journal of the Chemical Society(Resumed), volume 1954, issue 0, pages 3302-3313.doi:10.1039/JR9540003302

- ^abTakuya Echigo, Mitsuyoshi Kimata, and Teruyuki Maruoka (2007): "Crystal-chemical and carbon-isotopic characteristics of karpatite (C24H12) from the Picacho Peak Area, San Benito County, California: Evidences for the hydrothermal formation ".American Mineralogist,volume 92, issues 8-9, pages 1262–1269. doi:10.2138/am.2007.2509

- ^František Mikeš, Geraldine Boshart, and Emanuel Gil-Av (1976): "Resolution of optical isomers by high-performance liquid chromatography, using coated and bonded chiral charge-transfer complexing agents as stationary phases".Journal of Chromatography A,volume 122, pages 205-221.doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)82245-1

- ^František Mikeš, Geraldine Boshart, and Emanuel Gil-Av (1976): "Helicenes. Resolution on chiral charge-transfer complexing agents using high performance liquid chromatography".Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications,volume 1976, issue 3, pages 99-100.doi:10.1039/C39760000099

- ^abcdIvan Gutman and Sven J. Cyvin (2012):Introduction to the Theory of Benzenoid Hydrocarbons.152 pages.ISBN9783642871436

- ^Clar, E. (1964).Polycyclic Hydrocarbons.New York, NY:Academic Press.LCCN63012392.

- ^Portella, G.; Poater, J.; Solà, M. (2005). "Assessment of Clar's aromatic π-sextet rule by means of PDI, NICS and HOMA indicators of local aromaticity".Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry.18(8): 785–791.doi:10.1002/poc.938.

- ^Chen, T.-A.; Liu, R.-S. (2011). "Synthesis of Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons from Bis(biaryl)diynes: Large PAHs with Low Clar Sextets".Chemistry: A European Journal.17(21): 8023–8027.doi:10.1002/chem.201101057.PMID21656594.

- ^Stevenson, Philip E. (1964). "The ultraviolet spectra of aromatic hydrocarbons: Predicting substitution and isomerism changes".Journal of Chemical Education.41(5): 234–239.Bibcode:1964JChEd..41..234S.doi:10.1021/ed041p234.

- ^Feng, Xinliang; Pisula, Wojciech; Müllen, Klaus (2009)."Large polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Synthesis and discotic organization".Pure and Applied Chemistry.81(2): 2203–2224.doi:10.1351/PAC-CON-09-07-07.S2CID98098882.

- ^"Addendum to Vol. 2. Health criteria and other supporting information",Guidelines for drinking-water quality(2nd ed.), Geneva: World Health Organization, 1998

- ^Castillo, Maximiliano; Metta-Magaña, Alejandro J.; Fortier, Skye (2016). "Isolation of gravimetrically quantifiable alkali metal arenides using 18-crown-6".New Journal of Chemistry.40(3): 1923–1926.doi:10.1039/C5NJ02841H.

- ^Ruoff, R. S.; Kadish, K. M.; Boulas, P.; Chen, E. C. M. (1995). "Relationship between the electron affinities and half-wave reduction potentials of fullerenes, aromatic hydrocarbons, and metal complexes".The Journal of Physical Chemistry.99(21): 8843–8850.doi:10.1021/j100021a060.

- ^Rieke, Reuben D.; Wu, Tse-Chong; Rieke, Loretta I. (1995). "Highly reactive calcium for the preparation of organocalcium reagents: 1-adamantyl calcium halides and their addition to ketones: 1-(1-adamantyl)cyclohexanol".Organic Syntheses.72:147.doi:10.15227/orgsyn.072.0147.

- ^abcdefghRamesh, A.; Archibong, A.; Hood, D. B.; et al. (2011). "Global environmental distribution and human health effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons".Global Contamination Trends of Persistent Organic Chemicals.Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 97–126.ISBN978-1-4398-3831-0.

- ^abAbdel-Shafy, Hussein I. (2016)."A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation".Egyptian Journal of Petroleum.25(1): 107–123.doi:10.1016/j.ejpe.2015.03.011.

- ^"Wood burners cause nearly half of urban air pollution cancer risk – study".The Guardian.17 December 2021.Retrieved16 January2022.

- ^Tsiodra, Irini; Grivas, Georgios; Tavernaraki, Kalliopi; et al. (7 December 2021)."Annual exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban environments linked to wintertime wood-burning episodes".Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.21(23): 17865–17883.Bibcode:2021ACP....2117865T.doi:10.5194/acp-21-17865-2021.ISSN1680-7316.S2CID245103794.

- ^abTobiszewski, M.; Namieśnik, J. (2012). "PAH diagnostic ratios for the identification of pollution emission sources".Environmental Pollution.162:110–119.doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2011.10.025.ISSN0269-7491.PMID22243855.

- ^Bootdee, Susira; Chantara, Somporn; Prapamontol, Tippawan (2016-07-01)."Determination of PM2.5 and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from incense burning emission at shrine for health risk assessment".Atmospheric Pollution Research.7(4): 680–689.Bibcode:2016AtmPR...7..680B.doi:10.1016/j.apr.2016.03.002.ISSN1309-1042.

- ^abcdefghijkRavindra, K.; Sokhi, R.; Van Grieken, R. (2008). "Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source attribution, emission factors and regulation".Atmospheric Environment.42(13): 2895–2921.Bibcode:2008AtmEn..42.2895R.doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.12.010.hdl:2299/1986.ISSN1352-2310.S2CID2388197.

- ^Sörensen, Anja; Wichert, Bodo. "Asphalt and Bitumen".Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry.Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.doi:10.1002/14356007.a03_169.pub2.ISBN978-3527306732.

- ^"QRPOIL".www.qrpoil.com.Archived fromthe originalon 2016-03-04.Retrieved2018-07-19.

- ^Stephen A. Wise, Robert M. Campbell, W. Raymond West, et al. (1986): "Characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon minerals curtisite, idrialite and pendletonite using high-performance liquid chromatography, gas chromatography, mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy".Chemical Geology,volume 54, issues 3–4, pages 339-357.doi:10.1016/0009-2541(86)90148-8

- ^Max Blumer (1975): "Curtisite, idrialite and pendletonite, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon minerals: Their composition and origin"Chemical Geology,volume 16, issue 4, pages 245-256.doi:10.1016/0009-2541(75)90064-9

- ^Tetsuya Arinobu, Ryoshi Ishiwatari, Kunio Kaiho, and Marcos A. Lamolda (1999): "Spike of pyrosynthetic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with an abrupt decrease in δ13C of a terrestrial biomarker at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary at Caravaca, Spain ".Geology,volume 27, issue 8, pages 723–726doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0723:SOPPAH>2.3.CO;2

- ^abSvea Hernandez: Shining Light on the CO-dark Molecular Gas in the Heart of M83,retrieved2022-01-09

- ^Robert Hurt (2005-06-27)."Understanding Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons".Spitzer Space Telescope.Retrieved2018-04-21.

- ^López Puertas, Manuel (2013-06-06)."PAHs in Titan's Upper Atmosphere".CSIC.Archived fromthe originalon 2013-12-03.Retrieved2013-06-06.

- ^Meyers, Philip A.; Ishiwatari, Ryoshi (September 1993)."Lacustrine organic geochemistry—an overview of indicators of organic matter sources and diagenesis in lake sediments"(PDF).Organic Geochemistry.20(7): 867–900.Bibcode:1993OrGeo..20..867M.doi:10.1016/0146-6380(93)90100-P.hdl:2027.42/30617.S2CID36874753.

- ^Silliman, J. E.; Meyers, P. A.; Eadie, B. J.; Val Klump, J. (2001). "A hypothesis for the origin of perylene based on its low abundance in sediments of Green Bay, Wisconsin".Chemical Geology.177(3–4): 309–322.Bibcode:2001ChGeo.177..309S.doi:10.1016/S0009-2541(00)00415-0.ISSN0009-2541.

- ^Wakeham, Stuart G.; Schaffner, Christian; Giger, Walter (March 1980). "Poly cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Recent lake sediments—II. Compounds derived from biogenic precursors during early diagenesis".Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta.44(3): 415–429.Bibcode:1980GeCoA..44..415W.doi:10.1016/0016-7037(80)90041-1.

- ^Walker, T. R.; MacAskill, D.; Rushton, T.; et al. (2013). "Monitoring effects of remediation on natural sediment recovery in Sydney Harbour, Nova Scotia".Environmental Monitoring and Assessment.185(10): 8089–107.doi:10.1007/s10661-013-3157-8.PMID23512488.S2CID25505589.

- ^Walker, T. R.; MacAskill, D.; Weaver, P. (2013). "Environmental recovery in Sydney Harbour, Nova Scotia: Evidence of natural and anthropogenic sediment capping".Marine Pollution Bulletin.74(1): 446–52.Bibcode:2013MarPB..74..446W.doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.06.013.PMID23820194.

- ^Walker, T. R.; MacAskill, N. D.; Thalheimer, A. H.; Zhao, L. (2017). "Contaminant mass flux and forensic assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Tools to inform remediation decision making at a contaminated site in Canada".Remediation Journal.27(4): 9–17.Bibcode:2017RemJ...27d...9W.doi:10.1002/rem.21525.

- ^abcChoi, H.; Harrison, R.; Komulainen, H.; Delgado Saborit, J. (2010)."Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons".WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants.Geneva: World Health Organization.

- ^abcJohnsen, Anders R.; Wick, Lukas Y.; Harms, Hauke (2005). "Principles of microbial PAH degradation in soil".Environmental Pollution.133(1): 71–84.doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2004.04.015.ISSN0269-7491.PMID15327858.

- ^Mackay, D.; Callcott, D. (1998). "Partitioning and Physical Chemical Properties of PAHs". In Neilson, A. (ed.).PAHs and Related Compounds.The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Vol. 3 / 3I. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 325–345.doi:10.1007/978-3-540-49697-7_8.ISBN978-3-642-08286-3.

- ^Atkinson, R.; Arey, J. (1994-10-01)."Atmospheric chemistry of gas-phase polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: formation of atmospheric mutagens".Environmental Health Perspectives.102(Suppl 4): 117–126.doi:10.2307/3431940.ISSN0091-6765.JSTOR3431940.PMC1566940.PMID7821285.

- ^Srogi, K. (2007-11-01)."Monitoring of environmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a review".Environmental Chemistry Letters.5(4): 169–195.doi:10.1007/s10311-007-0095-0.ISSN1610-3661.PMC5614912.PMID29033701.

- ^abHaritash, A. K.; Kaushik, C. P. (2009). "Biodegradation aspects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): A review".Journal of Hazardous Materials.169(1–3): 1–15.doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.03.137.ISSN0304-3894.PMID19442441.

- ^abcdChoi, H.; Harrison, R.; Komulainen, H.; Delgado Saborit, J. (2010)."Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons".WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants.Geneva: World Health Organization.

- ^Dobrogowski, Miłosz; Wesołowski, Wiktor; Kucharska, Małgorzata; et al. (2014-01-01)."Chemical composition of surgical smoke formed in the abdominal cavity during laparoscopic cholecystectomy – Assessment of the risk to the patient".International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health.27(2): 314–25.doi:10.2478/s13382-014-0250-3.ISSN1896-494X.PMID24715421.

- ^Kim, K.-H.; Jahan, S. A.; Kabir, E. (2011). "A review of diseases associated with household air pollution due to the use of biomass fuels".Journal of Hazardous Materials.192(2): 425–431.doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.05.087.ISSN0304-3894.PMID21705140.

- ^Phillips, D. H. (1999). "Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the diet".Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis.443(1–2): 139–147.doi:10.1016/S1383-5742(99)00016-2.ISSN1383-5718.PMID10415437.

- ^Berrigan, David; Freedman, Neal D. (January 2024)."Invited Perspective: Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons in Alcohol—An Unappreciated Carcinogenic Mechanism?".Environmental Health Perspectives.132(1).doi:10.1289/EHP14255.ISSN0091-6765.PMC10798426.PMID38241190.

- ^abSrogi, K. (2007)."Monitoring of environmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a review".Environmental Chemistry Letters.5(4): 169–195.doi:10.1007/s10311-007-0095-0.ISSN1610-3661.PMC5614912.PMID29033701.

- ^abBoffetta, P.; Jourenkova, N.; Gustavsson, P. (1997). "Cancer risk from occupational and environmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons".Cancer Causes & Control.8(3): 444–472.doi:10.1023/A:1018465507029.ISSN1573-7225.PMID9498904.S2CID35174373.

- ^abWagner, M.; Bolm-Audorff, U.; Hegewald, J.; et al. (2015)."Occupational polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and risk of larynx cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis".Occupational and Environmental Medicine.72(3): 226–233.doi:10.1136/oemed-2014-102317.ISSN1470-7926.PMID25398415.S2CID25991349.Retrieved2015-04-13.

- ^abDavis, Emily; Walker, Tony R.; Adams, Michelle; et al. (July 2019)."Source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in small craft harbor (SCH) surficial sediments in Nova Scotia, Canada".Science of the Total Environment.691:528–537.Bibcode:2019ScTEn.691..528D.doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.114.PMC8190821.PMID31325853.

- ^abcdeHylland, K. (2006). "Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) ecotoxicology in marine ecosystems".Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A.69(1–2): 109–123.Bibcode:2006JTEHA..69..109H.doi:10.1080/15287390500259327.ISSN1528-7394.PMID16291565.S2CID23704718.

- ^Achten, C.; Hofmann, T. (2009). "Native polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in coals – A hardly recognized source of environmental contamination".Science of the Total Environment.407(8): 2461–2473.Bibcode:2009ScTEn.407.2461A.doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.12.008.ISSN0048-9697.PMID19195680.

- ^Jørgensen, A.; Giessing, A. M. B.; Rasmussen, L. J.; Andersen, O. (2008)."Biotransformation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in marine polychaetes"(PDF).Marine Environmental Research.65(2): 171–186.Bibcode:2008MarER..65..171J.doi:10.1016/j.marenvres.2007.10.001.ISSN0141-1136.PMID18023473.S2CID6404851.

- ^abJohnsen, A. R.; Wick, L. Y.; Harms, H. (2005). "Principles of microbial PAH-degradation in soil".Environmental Pollution.133(1): 71–84.doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2004.04.015.ISSN0269-7491.PMID15327858.

- ^Lundstedt, S.; White, P. A.; Lemieux, C. L.; et al. (2007). "Sources, fate, and toxic hazards of oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) at PAH- contaminated sites".Ambio: A Journal of the Human Environment.36(6): 475–485.doi:10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[475:SFATHO]2.0.CO;2.ISSN0044-7447.PMID17985702.S2CID36295655.

- ^Fu, P. P.; Xia, Q.; Sun, X.; Yu, H. (2012). "Phototoxicity and Environmental Transformation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)—Light-Induced Reactive Oxygen Species, Lipid Peroxidation, and DNA Damage".Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part C.30(1): 1–41.Bibcode:2012JESHC..30....1F.doi:10.1080/10590501.2012.653887.ISSN1059-0501.PMID22458855.S2CID205722865.

- ^abcVane, Christopher H.; Kim, Alexander W.; Beriro, Darren J.; et al. (2014)."Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) in urban soils of Greater London, UK".Applied Geochemistry.51:303–314.Bibcode:2014ApGC...51..303V.doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2014.09.013.ISSN0883-2927.

- ^Cave, Mark R.; Wragg, Joanna; Harrison, Ian; et al. (2010)."Comparison of Batch Mode and Dynamic Physiologically Based Bioaccessibility Tests for PAHs in Soil Samples"(PDF).Environmental Science & Technology.44(7): 2654–2660.Bibcode:2010EnST...44.2654C.doi:10.1021/es903258v.ISSN0013-936X.PMID20201516.

- ^abcVane, Christopher H.; Rawlins, Barry G.; Kim, Alexander W.; et al. (2013). "Sedimentary transport and fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) from managed burning of moorland vegetation on a blanket peat, South Yorkshire, UK".Science of the Total Environment.449:81–94.Bibcode:2013ScTEn.449...81V.doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.043.ISSN0048-9697.PMID23416203.

- ^Vane, C. H.; Harrison, I.; Kim, A. W.; et al. (2008)."Status of organic pollutants in surface sediments of Barnegat Bay-Little Egg Harbor Estuary, New Jersey, USA"(PDF).Marine Pollution Bulletin.56(10): 1802–1808.Bibcode:2008MarPB..56.1802V.doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.07.004.ISSN0025-326X.PMID18715597.

- ^abcVane, C. H.; Chenery, S. R.; Harrison, I.; et al. (2011)."Chemical signatures of the Anthropocene in the Clyde estuary, UK: sediment-hosted Pb,207/206Pb, total petroleum hydrocarbon, polyaromatic hydrocarbon and polychlorinated biphenyl pollution records "(PDF).Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences.369(1938): 1085–1111.Bibcode:2011RSPTA.369.1085V.doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0298.ISSN1364-503X.PMID21282161.S2CID1480181.

- ^Vane, Christopher H.; Beriro, Darren J.; Turner, Grenville H. (2015)."Rise and fall of mercury (Hg) pollution in sediment cores of the Thames Estuary, London, UK"(PDF).Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.105(4): 285–296.doi:10.1017/S1755691015000158.ISSN1755-6910.

- ^Langston, W. J.; O'Hara, S.; Pope, N. D.; et al. (2011)."Bioaccumulation surveillance in Milford Haven Waterway"(PDF).Environmental Monitoring and Assessment.184(1): 289–311.doi:10.1007/s10661-011-1968-z.ISSN0167-6369.PMID21432028.S2CID19881327.

- ^abVane, C.; Harrison, I.; Kim, A. (2007)."Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in sediments from the Mersey Estuary, U.K"(PDF).Science of the Total Environment.374(1): 112–126.Bibcode:2007ScTEn.374..112V.doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.12.036.ISSN0048-9697.PMID17258286.

- ^Vane, C. H.; Harrison, I.; Kim, A. W.; et al. (2009)."Organic and metal contamination in surface mangrove sediments of South China"(PDF).Marine Pollution Bulletin.58(1): 134–144.Bibcode:2009MarPB..58..134V.doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.09.024.ISSN0025-326X.PMID18990413.

- ^abcBostrom, C.-E.; Gerde, P.; Hanberg, A.; et al. (2002)."Cancer risk assessment, indicators, and guidelines for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air".Environmental Health Perspectives.110(Suppl. 3): 451–488.doi:10.1289/ehp.02110s3451.ISSN0091-6765.PMC1241197.PMID12060843.

- ^Loeb, L. A.; Harris, C. C. (2008)."Advances in Chemical Carcinogenesis: A Historical Review and Prospective".Cancer Research.68(17): 6863–6872.doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2852.ISSN0008-5472.PMC2583449.PMID18757397.

- ^abcdeDipple, A. (1985). "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Carcinogenesis".Polycyclic Hydrocarbons and Carcinogenesis.ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 283. American Chemical Society. pp. 1–17.doi:10.1021/bk-1985-0283.ch001.ISBN978-0-8412-0924-4.

- ^International Agency for Research on Cancer (1984).Polynuclear Aromatic Compounds, Part 3, Industrial Exposures in Aluminium Production, Coal Gasification, Coke Production, and Iron and Steel Founding(Report). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, France: World Health Organization. pp. 89–92, 118–124. Archived fromthe originalon April 7, 2010.Retrieved2016-02-13.

- ^abcBaird, W. M.; Hooven, L. A.; Mahadevan, B. (2015-02-01). "Carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts and mechanism of action".Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis.45(2–3): 106–114.doi:10.1002/em.20095.ISSN1098-2280.PMID15688365.S2CID4847912.

- ^Slaga, T. J. (1984). "Chapter 7: Multistage skin carcinogenesis: A useful model for the study of the chemoprevention of cancer".Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica.55(S2): 107–124.doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1984.tb02485.x.ISSN1600-0773.PMID6385617.

- ^abcXue, W.; Warshawsky, D. (2005). "Metabolic activation of polycyclic and heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and DNA damage: A review".Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology.206(1): 73–93.doi:10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.006.ISSN0041-008X.PMID15963346.

- ^Shimada, T.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y. (2004-01-01)."Metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to carcinogens by cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1B1".Cancer Science.95(1): 1–6.doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03162.x.ISSN1349-7006.PMID14720319.S2CID26021902.

- ^Androutsopoulos, V. P.; Tsatsakis, A. M.; Spandidos, D. A. (2009)."Cytochrome P450 CYP1A1: wider roles in cancer progression and prevention".BMC Cancer.9(1): 187.doi:10.1186/1471-2407-9-187.ISSN1471-2407.PMC2703651.PMID19531241.

- ^abHenkler, F.; Stolpmann, K.; Luch, Andreas (2012). "Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Bulky DNA Adducts and Cellular Responses". In Luch, A. (ed.).Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology.Experientia Supplementum. Vol. 101. Springer Basel. pp. 107–131.doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-8340-4_5.ISBN978-3-7643-8340-4.PMID22945568.

- ^abcNebert, D. W.; Dalton, T. P.; Okey, A. B.; Gonzalez, F. J. (2004)."Role of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-mediated Induction of the CYP1 Enzymes in Environmental Toxicity and Cancer".Journal of Biological Chemistry.279(23): 23847–23850.doi:10.1074/jbc.R400004200.ISSN1083-351X.PMID15028720.

- ^abRamesh, A.; Walker, S. A.; Hood, D. B.; et al. (2004)."Bioavailability and risk assessment of orally ingested polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons".International Journal of Toxicology.23(5): 301–333.doi:10.1080/10915810490517063.ISSN1092-874X.PMID15513831.S2CID41215420.

- ^Korashy, H. M.; El-Kadi, A. O. S. (2006). "The Role of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Diseases".Drug Metabolism Reviews.38(3): 411–450.doi:10.1080/03602530600632063.ISSN0360-2532.PMID16877260.S2CID30406435.

- ^abLewtas, J. (2007). "Air pollution combustion emissions: Characterization of causative agents and mechanisms associated with cancer, reproductive, and cardiovascular effects".Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research.The Sources and Potential Hazards of Mutagens in Complex Environmental Matrices – Part II.636(1–3): 95–133.doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.08.003.ISSN1383-5742.PMID17951105.

- ^abcdRamos, Kenneth S.; Moorthy, Bhagavatula (2005). "Bioactivation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Carcinogens within the vascular Wall: Implications for Human Atherogenesis".Drug Metabolism Reviews.37(4): 595–610.doi:10.1080/03602530500251253.ISSN0360-2532.PMID16393887.S2CID25713047.

- ^Kunzli, N.; Tager, I. (2005)."Air pollution: from lung to heart"(PDF).Swiss Medical Weekly.135(47–48): 697–702.doi:10.4414/smw.2005.11025.PMID16511705.S2CID28408634.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2016-10-09.Retrieved2015-12-16.

- ^Ridker, P. M. (2009). "C-Reactive Protein: Eighty Years from Discovery to Emergence as a Major Risk Marker for Cardiovascular Disease".Clinical Chemistry.55(2): 209–215.doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.119214.ISSN1530-8561.PMID19095723.

- ^Rossner, P. Jr.; Sram, R. J. (2012). "Immunochemical detection of oxidatively damaged DNA".Free Radical Research.46(4): 492–522.doi:10.3109/10715762.2011.632415.ISSN1071-5762.PMID22034834.S2CID44543315.

- ^Sram, R. J.; Binkova, B.; Dejmek, J.; Bobak, M. (2005)."Ambient Air Pollution and Pregnancy Outcomes: A Review of the Literature".Environmental Health Perspectives.113(4): 375–382.doi:10.1289/ehp.6362.ISSN0091-6765.PMC1278474.PMID15811825.

- ^Winans, B.; Humble, M.; Lawrence, B. P. (2011)."Environmental toxicants and the developing immune system: A missing link in the global battle against infectious disease?".Reproductive Toxicology.31(3): 327–336.doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.09.004.PMC3033466.PMID20851760.

- ^Wormley, D. D.; Ramesh, A.; Hood, D. B. (2004). "Environmental contaminant–mixture effects on CNS development, plasticity, and behavior".Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology.197(1): 49–65.doi:10.1016/j.taap.2004.01.016.ISSN0041-008X.PMID15126074.

- ^Suades-González, E.; Gascon, M.; Guxens, M.; Sunyer, J. (2015)."Air Pollution and Neuropsychological Development: A Review of the Latest Evidence".Endocrinology.156(10): 3473–3482.doi:10.1210/en.2015-1403.ISSN0013-7227.PMC4588818.PMID26241071.

- ^abcKim, Ki-Hyun; Jahan, Shamin Ara; Kabir, Ehsanul; Brown, Richard J. C. (2013-10-01). "A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their human health effects".Environment International.60:71–80.doi:10.1016/j.envint.2013.07.019.ISSN0160-4120.PMID24013021.

- ^European Union (2013-12-06),Commission Regulation (EU) 1272/2013,retrieved2016-02-01

- ^Keith, Lawrence H. (2014-12-08). "The Source of U.S. EPA's Sixteen PAH Priority Pollutants".Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds.35(2–4): 147–160.doi:10.1080/10406638.2014.892886.ISSN1040-6638.S2CID98493548.

- ^Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) (1995).Toxicological profile for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)(Report). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.Retrieved2015-05-06.

- ^abEFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) (2008). Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Food: Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (Report). Parma, Italy: European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). pp. 1–4.

- ^"NASA Ames PAH IR Spectroscopic Database".www.astrochem.org.

- ^Sasaki, Tatsuya; Yamada, Yasuhiro; Sato, Satoshi (2018-09-18). "Quantitative Analysis of Zigzag and Armchair Edges on Carbon Materials with and without Pentagons Using Infrared Spectroscopy".Analytical Chemistry.90(18): 10724–10731.doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.8b00949.ISSN0003-2700.PMID30079720.S2CID51920955.

- ^Carey, Bjorn (2005-10-18)."Life's Building Blocks 'Abundant in Space'".Space.com.Retrieved2014-03-03.

- ^Hudgins, D. M.; Bauschlicher, C. W. Jr; Allamandola, L. J. (2005). "Variations in the Peak Position of the 6.2 μm Interstellar Emission Feature: A Tracer of N in the Interstellar Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Population".Astrophysical Journal.632(1): 316–332.Bibcode:2005ApJ...632..316H.CiteSeerX10.1.1.218.8786.doi:10.1086/432495.S2CID7808613.

- ^Clavin, Whitney (2015-02-10)."Why Comets Are Like Deep Fried Ice Cream".NASA.Retrieved2015-02-10.

- ^abBattersby, S. (2004)."Space molecules point to organic origins".New Scientist.Retrieved2009-12-11.

- ^abMulas, G.; Malloci, G.;Joblin, C.;Toublanc, D. (2006). "Estimated IR and phosphorescence emission fluxes for specific polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the Red Rectangle".Astronomy and Astrophysics.446(2): 537–549.arXiv:astro-ph/0509586.Bibcode:2006A&A...446..537M.doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053738.S2CID14545794.

- ^Staff (2010-07-28)."Bright Lights, Green City".NASA.Retrieved2014-06-13.

- ^abStaff (2012-09-20)."NASA Cooks Up Icy Organics to Mimic Life's Origins".Space.com.Retrieved2012-09-22.

- ^abGudipati, M. S.; Yang, R. (2012). "In-Situ Probing Of Radiation-Induced Processing Of Organics In Astrophysical Ice Analogs—Novel Laser Desorption Laser Ionization Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectroscopic Studies".The Astrophysical Journal Letters.756(1): L24.Bibcode:2012ApJ...756L..24G.doi:10.1088/2041-8205/756/1/L24.S2CID5541727.

- ^""A Prebiotic Earth" – Missing Link Found on Saturn's Moon Titan ".DailyGalaxy.com.11 October 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 14 Aug 2021.Retrieved11 October2018.

- ^Zhao, Long; et al. (8 October 2018)."Low-temperature formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Titan's atmosphere".Nature Astronomy.2(12): 973–979.Bibcode:2018NatAs...2..973Z.doi:10.1038/s41550-018-0585-y.S2CID105480354.

External links

[edit]- ATSDR - Toxicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- Fused Ring and Bridged Fused Ring Nomenclature

- Database of PAH structures

- Cagliari PAH Theoretical Database

- NASA Ames PAH IR Spectroscopic Database

- National Pollutant Inventory: Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Fact Sheet

- Understanding Polycyclic Aromatic HydrocarbonsNASA Spitzer Space Telescope

- "The Aromatic World: An Interview with Professor Pascale Ehrenfreund"fromAstrobiology Magazine

- Oregon State University Superfund Research Centerfocused on new technologies and emerging health risks of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)

- Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)--EPA Fact Sheet.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Solid Waste, January 2008.

![Benzo[a]pyrene](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Benzo-a-pyrene.svg/120px-Benzo-a-pyrene.svg.png)

![Benzo[ghi]perylene](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/ff/Benzo%28ghi%29perilene.png/120px-Benzo%28ghi%29perilene.png)

![Benzo[c]fluorene](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4f/Benzocfluorene.svg/120px-Benzocfluorene.svg.png)