Prince Edward Islands

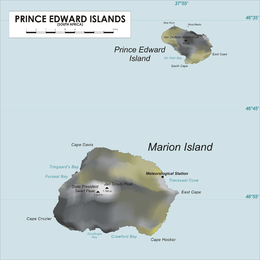

Map of Prince Edward Islands | |

Orthographic projection centred on the Prince Edward Islands | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Indian Ocean |

| Coordinates | 46°52′48″S37°45′00″E/ 46.88000°S 37.75000°E |

| Area | 335 km2(129 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,230 m (4040 ft) |

| Highest point | Mascarin Peak |

| Administration | |

| Province | Western Cape |

| Municipality | City of Cape Town |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 (permanent) 50 (non-permanent research staff) |

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Designated | 24 January 1997 |

| Reference no. | 1688[1] |

ThePrince Edward Islandsare two small uninhabitedvolcanic islandsin thesub-AntarcticIndian Oceanthat are administered bySouth Africa.They are namedMarion Island(named afterMarc-Joseph Marion du Fresne,1724–1772) andPrince Edward Island(named afterPrince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn,1767–1820).

The islands in the group have been declared Special Nature Reserves under the South African Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act, No. 57 of 2003, and activities on the islands are therefore restricted to research and conservation management.[2][3]Further protection was granted when the area was declared amarine protected areain 2013.[4][5]The only human inhabitants of the islands are the staff of ameteorologicalandbiologicalresearch station run by theSouth African National Antarctic Programmeon Marion Island.

History

[edit]

Barent Barentszoon Lam of theDutch East India Companyreached the islands on 4 March 1663 on the shipMaerseveen.They were namedDina(Prince Edward) andMaerseveen(Marion),[6]but the islands were erroneously recorded to be at 41° South, and neither were found again by subsequent Dutch sailors.[7][8]

In January 1772, the French frigateLe Mascarin,captained byMarc-Joseph Marion du Fresne,visited the islands and spent five days trying to land, thinking they had foundAntarctica(then not yet proven to exist).[9]Marion named the islandsTerre de l'Espérance(Marion) andIle de la Caverne(Prince Edward).[7]After failing to land,Le Mascarincontinued eastward, discovering theCrozet Islandsand landing atNew Zealand,where Marion du Fresne and some of his crew were killed by local Māoris.

Julien Crozet, navigator and second in command ofLe Mascarin,survived the disaster, and happened to meetJames CookatCape Townin 1776, at the onset of Cook'sthird voyage.[10]Crozet shared the charts of his ill-fated expedition, and as Cook sailed from Cape Town, he passed the islands on 13 December, but was unable to attempt a landing due to bad weather.[9]Cook named the islands afterPrince Edward,the fourth son of KingGeorge III;and though he is also often credited with naming the larger island Marion, after Captain Marion, this name was adopted by sealers and whalers who later hunted the area, to distinguish the two islands.[11]

The first recorded landing on the islands was in 1799 by a group of Frenchsealhunters of theSally.[11]Another landing in late 1803 by a group of seal hunters led by American captain Henry Fanning of theCatharinefound signs of earlier human occupation.[12]The islands were frequented by sealers until about 1810, when the local fur seal populations had been nearly eradicated.[11]The first scientific expedition to the islands was led byJames Clark Ross,who visited in 1840 during hisexplorationof the Antarctic, but was unable to land.[11]Ross sailed along the islands on 21 April 1840. He made observations on vast numbers of penguins ( "groups of many thousands each" ), and other kinds of sea-birds. He also sawfur seals,which he supposed to be of the speciesArctocephalus falklandicus.[13]The islands were finally surveyed during theChallengerExpedition,led by CaptainGeorge Nares,in 1873.[14]

The sealing era lasted from 1799 to 1913. During that period visits by 103 vessels are recorded, seven of which ended in shipwreck.[15]Sealing relics include irontrypots,the ruins of huts and inscriptions. The occasional modern sealing vessel visited fromCape Town,South Africa,in the 1920s.

The islands have been the location of other shipwrecks. In June 1849 the brigRichard Dart,with a troop of Royal Engineers under Lt. James Liddell, was wrecked on Prince Edward Island; only 10 of the 63 on board survived to be rescued by elephant seal hunters from Cape Town.[16]In 1908 the Norwegian vesselSolglimtwas shipwrecked on Marion Island, and survivors established a short-lived village at the north coast, before being rescued.[12][17][18]The wreck of theSolglimtis the best-known in the islands, and is accessible to divers.[12]

On 22 September 1979, a US surveillance satellite known as Vela 6911 noted an unidentified double flash of light, known as theVela incident,in the waters off the islands. There was and continues to be considerable controversy over whether this event was perhaps an undeclared nuclear test carried out bySouth Africa and Israelor some other event.[19]The cause of the flash remains officially unknown, and some information about the event remainsclassified.[20]Today, most independent researchers believe that the 1979 flash was caused by a nuclear explosion.[20][21][22][23]

In 2003, the South African government declared the Prince Edward Islands a Special Nature Reserve, and in 2013 declared 180,000 km2(69,000 sq mi) of ocean waters around the islands a Marine Protection Area, thus creating one of the world's largestenvironmental protectionareas.[5]

Marion Research Station

[edit]Marion Island Base | |

|---|---|

Location in Prince Edward Islands | |

| Coordinates:46°52′32″S37°51′31″E/ 46.875460°S 37.858540°E | |

| Country | |

| Operator | SANAP |

| Established | 1948 |

| Elevation | 22 m (72 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Summer | 18 |

| • Winter | 18 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 |

| UN/LOCODE | ZA |

| Active times | All year-round |

| Status | Operational |

| Activities | List

|

| Website | sanap.ac.za |

In 1908, theBritish governmentassumed ownership of the islands. In late 1947 and early 1948, South Africa, with Britain's agreement, annexed the islands and installed themeteorologicalstation on Transvaal Cove on the north-east coast of Marion Island.[7]The research station was soon enlarged and today studies regional meteorology and the biology of the islands, in particular the birds (penguins,petrels,albatrosses,gulls) andseals.[24]

A new research base was built from 2001 to 2011 to replace older buildings on the site.[25]The access to the station is either by boat or helicopter.[26]A helipad and storage hangar is located behind the main base structure.[25][27]

In April 2017, scientists fromMcGill University,in collaboration with theSouth African National Antarctic Programme,launched a new astrophysical experiment on Marion Island called Probing Radio Intensity at high-Z from Marion (PRIZM), searching for signatures of thehydrogen linein the early universe.[28]In 2018, another cosmology experiment was launched by the McGill team called Array of Long Baseline Antennas for Taking Radio Observation from Sub-Antarctic (ALBATROS). The new experiment aims to create very high-resolution maps of the low-frequency radio emission from the universe, and take first steps towards detecting the cosmologicalDark Ages.[29]

Geography and geology

[edit]The island group is about 955nmi(1,769 km; 1,099 mi) south-east ofPort Elizabethin mainland South Africa. At 46 degrees latitude, its distance to theequatoris only slightly longer than to theSouth Pole.Marion Island (46°54′45″S37°44′37″E/ 46.91250°S 37.74361°E), the larger of the two, is 25.03 km (15.55 mi) long and 16.65 km (10.35 mi) wide with an area of 290 km2(112 sq mi) and a coastline of some 72 km (45 mi), most of which is high cliffs. The highest point on Marion Island isMascarin Peak(formerly State President Swart Peak), reaching 1,242 m (4,075 ft) above sea level.[30]Thetopographyof Marion Island includes many hillocks and small lakes, andboggylowland terrain with little vegetation.[31]

Prince Edward Island (46°38′39″S37°56′36″E/ 46.64417°S 37.94333°E) is much smaller—only about 45 km2(17 sq mi), 10.23 km (6.36 mi) long and 6.57 km (4.08 mi) wide—and lies some 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi) to the north-east of Marion Island. The terrain is generally rocky, with high cliffs (490 m (1,608 ft)) on its south western side.[31]At thevan Zinderen BakkerPeak north-west of the center, it reaches a height of 672 m (2,205 ft).[32]

There are a few offshore rocks along the northern coast of Prince Edward Island, like Ship Rock 100 m (328 ft) north of northernmost point, and Ross Rocks 500 m (1,640 ft) from the shore. Boot Rock is about 500 m (1,640 ft) off the northern coast of Marion Island.

Both islands are ofvolcanicorigin.[31]Marion Island is one of the peaks of a large underwatershield volcanothat rises some 5,000 m (16,404 ft) from the sea floor to the top of Mascarin Peak. The volcano is active, with eruptions having occurred between 1980 and 2004.[30]

-

Satellite image of Prince Edward Island, 2009.

-

Satellite image of Marion Island, 2009

Climate

[edit]Despite being located inside thesouth temperate zoneat 46 degrees latitude, the islands have atundra climate.They lie directly in the path of eastward-movingdepressionsall year round and this gives them an unusually cool and windy climate. Strong regional winds, known as theroaring forties,blow almost every day of the year, and the prevailing wind direction is north-westerly.[31]Annual rainfall averages from 2,400 mm (94.5 in) up to over 3,000 mm (118.1 in) on Mascarin Peak. In spite of its very chilly climate it is located closer to the equator than mild northern hemisphere climates such asParisandSeattleand only one degree farther south than fellow southern hemisphere climates such asComodoro RivadaviainArgentinaandAlexandrainNew Zealand.Many climates on lower latitudes in the Northern hemisphere have far colder winters than Prince Edward Islands due to the islands'maritimemoderation, even though temperatures in summer are much cooler than those normally found in maritime climates.

The islands are among the cloudiest places in the world; about 1300 hours a year of sunshine occur on the sheltered eastern side of Marion Island, but only around 800 hours occur away from the coast on the wet western sides of Marion and Prince Edward Islands.

Summer and winter have fairly similar climates with cold winds and threat of snow or frost at any time of the year. However, the mean temperature in February (midsummer) is 7.7 °C (45.9 °F) and in August (midwinter) it is 3.9 °C (39.0 °F).[33][34]

| Climate data for Marion Island (1991–2020, extremes 1949–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

22.9 (73.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

7.1 (44.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

8.8 (47.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

7.2 (45.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

4.5 (40.1) |

4.2 (39.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

7.3 (45.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.7 (42.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

4.3 (39.7) |

3.2 (37.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

1.9 (35.4) |

1.6 (34.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.2 (39.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 163.6 (6.44) |

155.4 (6.12) |

160.9 (6.33) |

153.3 (6.04) |

169.3 (6.67) |

162.7 (6.41) |

161.9 (6.37) |

144.9 (5.70) |

155.0 (6.10) |

139.7 (5.50) |

142.6 (5.61) |

158.5 (6.24) |

1,857 (73.11) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 17.9 | 15.1 | 17.1 | 16.0 | 18.8 | 19.7 | 21.0 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 15.9 | 16.8 | 17.8 | 212.6 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 83 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 85 | 84 | 83 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 84 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 158.9 | 135.4 | 125.8 | 98.3 | 82.0 | 59.1 | 66.9 | 88.2 | 106.0 | 133.6 | 150.8 | 164.4 | 1,311.7 |

| Source 1: NOAA (humidity 1961–1990)[35][36] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[37] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

[edit]

The islands are part of theSouthern Indian Ocean Islands tundraecoregionthat includes a small number ofsubantarcticislands. Because of the paucity of land masses in theSouthern Ocean,the islands host a wide variety of species and are critical toconservation.[5]In the cold subantarctic climate, plants are mainly limited to grasses,mosses,andkelp,whilelichensare the most visiblefungi.The main indigenous animals are insects (such as the seaweed-eating weevilPalirhoeus eatoni) along with large populations ofseabirds,seals[38]andpenguins.[39]

Birds

[edit]

The islands have been designated anImportant Bird Area(IBA) byBirdLife Internationalfor their significant seabird breeding populations.[40]At least thirty different species of birds are thought to breed on the islands, and it is estimated the islands support upwards of 5 million breeding seabirds, and 8 million seabirds total.[5]Five species ofalbatross(of which all are eitherthreatenedorendangered) are known to breed on the islands, including thewandering albatross,dark-mantled,light-mantled,Indian yellow-nosedandgrey-headed albatross.[5]

The islands also host fourteen species ofpetrel,four species ofprion,theAntarctic tern,and thebrown skua,among other seabirds.[5][39]Four penguin species are found:king penguins,Eastern rockhoppers,gentoosandmacaroni penguins.[39]

Mammals

[edit]Three species of seal breed on the islands: thesouthern elephant seal,theAntarctic fur seal,and theSubantarctic fur seal.[5]The waters surrounding the islands are often frequented by several species of whale, especiallyorcas,which prey on penguins and seals.[41]Large whales such assouthern rightsandsouthern humpbacks,andleopard sealsare seen more sporadically, and it remains unclear how large or stable their current local populations are, though it is thought their numbers are significantly down compared to the time of first human contact with the islands.[42]

The area saw heavy sealing and whaling operations in the nineteenth century and continued to be subject to mass illegal whaling until the 1970s, with theSoviet UnionandJapanallegedly continuing whaling operations into the 1990s.[43]Currently, the greatest ecological threat is thelongline fishingofPatagonian toothfish,which endangers a number of seabirds that dive into the water after baited hooks.[5]

Invasive species

[edit]The wildlife is particularly vulnerable tointroduced speciesand the historical problem has been with cats and mice.House micearrived to Marion Island with whaling and sealing ships in the 1800s and quickly multiplied, so much so that in 1949, five domestic cats were brought to the research base to deal with them.[44]The cats multiplied quickly, and by 1977 there were approximately 3,400 cats on the island, feeding on burrowing petrels in addition to mice, and taking an estimated 455,000 petrels a year.[45]Some species of petrels soon disappeared from Marion Island, and a cat eradication programme was established.[44]A few cats were intentionally infected with the highly specificfeline panleukopeniavirus, which reduced the cat population to about 600 by 1982.[46]The remaining cats were killed by nocturnal shooting, and in 1991 only eight cats were trapped in a 12-month period.[44][47][48]

It is believed that no cats remain on Marion Island today, and with the cats gone, the mouse population has sharply increased to "plague like" levels.[45]In 2003,ornithologistsdiscovered that in the absence of other food sources, the mice were attacking albatross chicks and eating them alive as they sat helplessly on their nests.[45]A similar problem has been observed onGough Island,where a mouse eradication programme began in 2021.[49]A programme to eradicate invasiveratsonSouth Georgia Islandwas completed in 2015, and as of 2016 the island appears to be completely rat free.[50]The geography of Marion Island presents certain obstacles not found on either Gough or South Georgia islands, particularly its large size, high elevations and variable weather.[45]An assessment of the island was completed in May 2015, led by notedinvasive speciesecologistJohn Parkes, with the general conclusion that an eradication programme is feasible, but will require precise planning.[51]

Both Gough Island and the Prince Edward Islands also suffer from invasiveprocumbent pearlwort(Sagina procumbens), which is transforming the uplandecosystemand is now considered beyond control.[52]

Legal status

[edit]

Marion Island and Prince Edward Island were claimed for South Africa on 29 December 1947 and 4 January 1948 respectively, by aSouth African Navyforce fromHMSASTransvaalunder the command ofJohn Fairbairn.[12]On 1 October 1948 the annexation was made official whenGovernor-GeneralGideon Brand van Zylsigned thePrince Edward Islands Act, 1948.In terms of the Act, the islands fall under the jurisdiction of theCape TownMagistrate's Court,andSouth African lawas applied in theWestern Capeapplies on them. The islands are also deemed to be situated within the electoral district containing thePort of Cape Town;as of 2016[update]this isward115 of theCity of Cape Town.

Amateur radio

[edit]

As of 2014[update],Marion Island, prefix ZS8, was the third most wantedDXCC"entity" by theamateur radiocommunity. By the end of 2014, it had dropped to 27th, after simultaneous activity by three licencees in the 2013/2014 team. However, their activity was mainly on voice. On Morse telegraphy, the Islands remain the second most wanted entity afterNorth Korea,while on data they are sixth out of 340.[53]

See also

[edit]- Crozet Islands

- Gough Island

- List of Antarctic islands north of 60° S

- List of protected areas of South Africa

- List of sub-Antarctic islands

- Prince Edward Fracture Zone

- S. A. Agulhas

- S. A. Agulhas II

- SANAE

- South African National Antarctic Programme

- Vela incident

Citations

[edit]- ^"Prince Edward Islands".RamsarSites Information Service.Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2019.Retrieved25 April2018.

- ^Cooper, John (June 2006)."Antarctica and Islands – Background Research Paper produced for the South Africa Environment Outlook report on behalf of the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism"(PDF).p. 6. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 14 May 2016.Retrieved5 October2010.

- ^1993 United Nations list of national parks and protected areas.World Conservation Monitoring Centre, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Commission on Natural Parks and Protected Areas, United Nations Environment Programme. 1993. p. 173.ISBN978-2-8317-0190-5.

- ^"Prince Edward Islands declared a Marine Protected Area".Department of Environmental Affairs, Republic of South Africa. 9 April 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2016.

- ^abcdefgh"Prince Edward Islands Marine Protected Area: A global treasure setting new conservation benchmarks"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 12 July 2016.

- ^Pieter Arend Leupe: De eilanden Dina en Maerseveen in den Zuider Atlantischen Oceaan; in: Verhandelingen en berigten betrekkelijk het zeewezen, de zeevaartkunde, de hydrographie, de koloniën en de daarmede in verband staande wetenschappen, Jg. 1868, Deel 28, Afd. 2, [No.] 9; Amsterdam 1868 (pp. 242–253); cf.Rubin, Jeff (2008).Antarctica.Lonely Planet. p. 233.ISBN978-1-74104-549-9.

- ^abc"Marion Island, South Indian Ocean".Btinternet.com. 29 June 2003. Archived fromthe originalon 29 July 2012.Retrieved9 October2012.

- ^"Marion and Prince Edward Islands".Archivedfrom the original on 22 March 2015.Retrieved21 September2016.

- ^abKeller, Conrad (1901)."XXII – The Prince Edward Isles".Madagascar, Mauritius and the other East-African islands.S. Sonnenschein & Co. pp. 224–225.Retrieved5 October2010.

- ^Hough, Richard (1995).Captain James Cook: A Biography.W. W. Norton & Company. pp.259–260.ISBN978-0393315196.

- ^abcdMills, William J. (2003).Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1.ABC-CLIO. p. 531.ISBN978-1576074220.Archivedfrom the original on 4 July 2014.Retrieved4 April2014.

- ^abcd"Marion Island – History".Sanap.ac.za. Archived fromthe originalon 24 July 2017.Retrieved9 October2012.

- ^Ross (1847),pp. 45–47, vol.1.

- ^Cooper, John (2008). "Human history". In Chown, Steven L.; Froneman, Pierre William (eds.).The Prince Edward Islands: Land-sea Interactions in a Changing Ecosystem.Stellenbosch, South Africa: Sun Press. pp. 331–350, page 336.ISBN978-1-920109-85-1.

- ^R.K. Headland,Historical Antarctic sealing industry,Scott Polar Research Institute (Cambridge University), 2018, p.167ISBN978-0-901021-26-7

- ^"Wreck of the troopship Richard Dart".Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2013.Retrieved26 March2014.

- ^"Four Weeks' Vigil of South Sea Crusoes".The Victoria Daily Times.28 January 1909. p. 8.Archivedfrom the original on 12 December 2019.Retrieved12 December2019– viaNewspapers.com.

- ^"ALSA to talk on Marion Island's forgotten history at a SCAR conference".24 August 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 23 September 2016.Retrieved21 September2016.

- ^Von Wielligh, Nic; Von Wielligh-Steyn, Lydia (2015).The Bomb – South Africa's Nuclear Weapons Programme.Pretoria, ZA: Litera.ISBN978-1-920188-48-1.OCLC930598649.

- ^abBurr, William; Cohen, Avner, eds. (8 December 2016).Vela Incident: South Atlantic Mystery Flash in September 1979 Raised Questions about Nuclear Test.National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 570(Report).Archivedfrom the original on 12 August 2017.Retrieved27 September2020.

- ^"Declassified documents indicate Israel and South Africa conducted nuclear test in 1979".9 December 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 8 November 2020.Retrieved27 September2020.

- ^Johnston, Martin (13 August 2018)."Researchers: Radioactive Australian sheep bolster nuclear weapon test claim against Israel".The New Zealand Herald.ISSN1170-0777.Archivedfrom the original on 13 August 2018.Retrieved13 August2018.

- ^De Geer, Lars-Erik; Wright, Christopher M. (2018)."The 22 September 1979 Vela Incident: Radionuclide and Hydroacoustic Evidence for a Nuclear Explosion"(PDF).Science & Global Security.26(1): 20–54.Bibcode:2018S&GS...26...20D.doi:10.1080/08929882.2018.1451050.ISSN0892-9882.S2CID126082091.Archived(PDF)from the original on 24 March 2020.Retrieved27 September2020.

- ^"Marion Island Marine Mammal Programme".Marionseals.com.Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2020.Retrieved15 February2021.

- ^abYeld, John (18 March 2011)."New Marion Island base opens".The Cape Argus (Independent Newspapers).Archivedfrom the original on 25 April 2016.

- ^"New Base Puts Sa on Top of the Weather".South African Garden Route. 21 March 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 25 November 2015.

- ^"Google Maps".Google Maps. 1 January 1970.Archivedfrom the original on 4 October 2013.Retrieved9 October2012.

- ^Philip, L.; Abdurashidova, Z.; Chiang, H. C.; et al. (2018). "Probing Radio Intensity at high-Z from Marion: 2017 Instrument".Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation.8(2): 1950004.arXiv:1806.09531.Bibcode:2019JAI.....850004P.doi:10.1142/S2251171719500041.S2CID119106726.

- ^Chiang, H. C.; Dyson, T.; Egan, E.; Eyono, S.; Ghazi, N.; Hickish, J.; Jáuregui-Garcia, J. M.; Manukha, V.; Ménard, T.; Moso, T.; Peterson, J.; Philip, L.; Sievers, J. L.; Tartakovsky, S. (2020). "The Array of Long Baseline Antennas for Taking Radio Observations from the Sub-Antarctic".Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation.09(4): 2050019–2050564.arXiv:2008.12208.Bibcode:2020JAI.....950019C.doi:10.1142/S2251171720500191.S2CID221340854.

- ^ab"Marion Island".Global Volcanism Program.Archivedfrom the original on 25 July 2015.Retrieved30 April2015.

- ^abcd"Marion Island".South African National Antarctic Program.Archived fromthe originalon 24 June 2014.Retrieved27 September2016.

- ^"Peakbagger – Van Zinderen Bakker Peak, South Africa".Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2015.Retrieved20 March2012.

- ^General Survey of Climatology, V12 (2001), Elsevier

- ^GISS Climate data averages for 1978 to 2007, source – GHCN

- ^"World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Marion Islands".National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.Retrieved20 January2024.

- ^"Marion Island Climate Normals 1961–1990".National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.Archivedfrom the original on 17 February 2022.Retrieved15 December2012.

- ^"Station Ile Marion"(in French). Meteo Climat.Archivedfrom the original on 13 December 2020.Retrieved11 June2016.

- ^"Marion Island Marine Mammal Programme".Marionseals.com.Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2020.Retrieved28 April2016.

- ^abc"Southern Indian Ocean Islands tundra".Terrestrial Ecoregions.World Wildlife Fund.

- ^"Prince Edward Islands Special Nature Reserve".BirdLife Data Zone.BirdLife International. 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 5 December 2020.Retrieved13 December2020.

- ^"Marion Island Marine Mammal Programme".Marionseals.com.Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2021.Retrieved15 February2021.

- ^M. Postma; M. Wege; M.N. Bester; D.S. van der Merwe (2011)."Inshore Occurrence of Southern Right Whales (Eubalaena australis) at Subantarctic Marion Island".African Zoology.46:188–193.doi:10.3377/004.046.0112.hdl:2263/16586.S2CID54744920.Archivedfrom the original on 17 February 2022.Retrieved9 March2016.

- ^Berzin A.; Ivashchenko V.Y.; Clapham J.P.; Brownell L. R.Jr. (2008)."The Truth About Soviet Whaling: A Memoir".DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska – Lincoln.Archivedfrom the original on 5 March 2016.Retrieved9 March2016.

- ^abcBloomer J.P.; Bester M.N. (1992)."Control of feral cats on sub-Antarctic Marion Island, Indian Ocean".Biological Conservation.60(3): 211–219.doi:10.1016/0006-3207(92)91253-O.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2016.Retrieved23 September2016.

- ^abcdJohn Yeld."Marion Island's Plague of Mice".Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2016.Retrieved23 September2016.

- ^K Berthier; M Langlais; P Auger; D Pontier (22 October 2000)."Dynamics of a feline virus with two transmission modes within exponentially growing host populations".BioInfoBank Library. Archived fromthe originalon 10 February 2012.

- ^de Bruyn P.J.N. & Oosthuizen W.C. (2017).Pain forms the Character: Doc Bester, Cat hunters & Sealers.Antarctic Legacy of South Africa.ISBN978-0-620-74912-1.

- ^"Cat hunter and sealer book – Marion Island Marine Mammal Programme".Marionseals.com.Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2021.Retrieved15 February2021.

- ^"The killer mice of Gough Island".Financial Times.27 May 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2016.Retrieved23 September2016.

- ^"Ridding South Georgia of rats and reindeer".Archivedfrom the original on 17 February 2022.Retrieved26 September2016.

- ^"Impressions of an expert. Field work to assess the feasibility of eradicating Marion Island's mice completed".Archivedfrom the original on 18 November 2019.Retrieved26 September2016.

- ^Cooper, J. et al.,"Earth, fire and water: applying novel techniques to eradicate the invasive plant, procumbent pearlwort Sagina procumbenss, on Gough Island, a World heritage Site in the South Atlantic"Archived4 March 2016 at theWayback Machine,Invasive Species Specialist Group, 2010, retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^"Club Log: DXCC Most-Wanted List for April 2016".Secure.clublog.org. 23 April 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 15 March 2015.Retrieved28 April2016.

General and cited sources

[edit]- LeMasurier, W. E.; Thomson, J. W., eds. (1990).Volcanoes of the Antarctic Plate and Southern Oceans.American Geophysical Union.ISBN978-0-87590-172-5.

- "Marion Island".Global Volcanism Program.Smithsonian Institution.

- "Prince Edward Island".Global Volcanism Program.Smithsonian Institution.

- Jenkins, Geoffrey (1979).Southtrap.William Collins, Sons and Co Ltd.ISBN978-0-00-616116-5.

- Ross, James Clark (1847)..London: John Murray – viaWikisource.

- de Bruyn P.J.N.; Oosthuizen W.C., eds. (2017)."Pain forms the Character: Doc Bester, Cat hunters & Sealers".Antarctic Legacy of South Africa.ISBN978-0-620-74912-1.

External links

[edit]- South African Research station on Marion Island– official website

- Facebook Pages– Marion Island team publications

- Facebook Groups– Marion Island team discussions

- Marion Island seal and killer whale research– Official Marion Island Marine Mammal Programme website

- No Pathway Here– An account of the annexation of the islands

- Earth Observatory– Image of the Day 18 October 2009

- Prince Edward Islands

- 1908 establishments in the British Empire

- Archipelagoes of the Indian Ocean

- Important Bird Areas of Indian Ocean islands

- Important Bird Areas of South Africa

- Important Bird Areas of subantarctic islands

- Indian Ocean islands of South Africa

- Integral overseas territories

- Island restoration

- Maritime history of South Africa

- Penguin colonies

- Polygenetic shield volcanoes

- Ramsar sites in South Africa

- Ridge volcanoes

- Seabird colonies

- Seal hunting

- South African National Antarctic Programme

- Subantarctic islands

- Uninhabited islands of South Africa

- Volcanic islands

- Volcanoes of South Africa

- Volcanoes of the Southern Ocean