Psychedelic drug

| Part ofa serieson |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

Psychedelicsare a subclass ofhallucinogenic drugswhose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary mental states (known aspsychedelic experiencesor "trips" ) and a perceived "expansion of consciousness".[2][3]Also referred to asclassic hallucinogensorserotonergic hallucinogens,the termpsychedelicis sometimes used more broadly to include various types of hallucinogens, such as those which are atypical or adjacent topsychedelialikesalviaandMDMA,respectively.[4]

Classic psychedelics generally cause specific psychological, visual, and auditory changes, and oftentimes a substantiallyaltered state of consciousness.[5][6]They have had the largest influence on science and culture, and includemescaline,LSD,psilocybin,andDMT.[7][8]

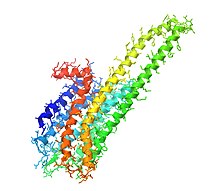

Most psychedelic drugs fall into one of the three families of chemical compounds:tryptamines,phenethylamines,orlysergamides(LSD is considered both a tryptamine and lysergamide). They act viaserotonin 2A receptor agonism.[2][9][10][11][4]When compounds bind to serotonin5-HT2Areceptors,[12]they modulate the activity of key circuits in the brain involved with sensory perception and cognition. However, the exact nature of how psychedelics induce changes in perception and cognition via the 5-HT2Areceptor is still unknown.[13]The psychedelic experience is often compared to non-ordinary forms of consciousness such as those experienced in meditation,[14][3]mystical experiences,[6][5]andnear-death experiences,[5]which also appear to be partially underpinned by altered default mode network activity.[15]The phenomenon ofego deathis often described as a key feature of the psychedelic experience.[14][3][5]

Many psychedelic drugs are illegal worldwide under theUN conventions,with occasional exceptions for religious use or research contexts. Despite these controls,recreational useof psychedelics is common.[16][17]Legal barriers have made the scientific study of psychedelics more difficult. Research has been conducted, however, and studies show that psychedelics are physiologically safe and rarely lead to addiction.[18][19]Studies conducted using psilocybin in apsychotherapeuticsetting reveal that psychedelic drugs may assist with treatingdepression,alcohol addiction,andnicotine addiction.[11][20]Although further research is needed, existing results suggest that psychedelics could be effective treatments for certain forms of psychopathology.[21][22][23][17]A 2022 survey found that 28% of Americans had used a psychedelic at some point in their life.[24]

Etymology and nomenclature[edit]

The termpsychedelicwas coined by the psychiatristHumphrey Osmondduring written correspondence with authorAldous Huxleyand presented to the New York Academy of Sciences by Osmond in 1957.[25]It is irregularly[26]derived from theGreekwords ψυχή (psychḗ,meaning 'mind, soul') and δηλείν (dēleín,meaning 'to manifest'), with the intended meaning "mind manifesting" or alternatively "soul manifesting", and the implication that psychedelics can reveal unused potentials of the human mind.[27]The term was loathed by AmericanethnobotanistRichard Schultesbut championed by American psychologistTimothy Leary.[28]

Aldous Huxley had suggested his own coinagephanerothyme(Greekphaneroein- "to make manifest or visible" and Greekthymos"soul", thus "to reveal the soul" ) to Osmond in 1956.[29]Recently, the termentheogen(meaning "that which produces the divine within" ) has come into use to denote the use of psychedelic drugs, as well as various other types of psychoactive substances, in a religious, spiritual, and mystical context.[30]

In 2004,David E. Nicholswrote the following about the nomenclature used for psychedelic drugs:[30]

Many different names have been proposed over the years for this drug class. The famous German toxicologist Louis Lewin used the name phantastica earlier in this century, and as we shall see later, such a descriptor is not so farfetched. The most popular names—hallucinogen, psychotomimetic, and psychedelic ( "mind manifesting" )—have often been used interchangeably.Hallucinogenis now, however, the most common designation in the scientific literature, although it is an inaccurate descriptor of the actual effects of these drugs. In the lay press, the termpsychedelicis still the most popular and has held sway for nearly four decades. Most recently, there has been a movement in nonscientific circles to recognize the ability of these substances to provoke mystical experiences and evoke feelings of spiritual significance. Thus, the termentheogen,derived from the Greek wordentheos,which means "god within", was introduced by Ruck et al. and has seen increasing use. This term suggests that these substances reveal or allow a connection to the "divine within". Although it seems unlikely that this name will ever be accepted in formal scientific circles, its use has dramatically increased in the popular media and on internet sites. Indeed, in much of the counterculture that uses these substances, entheogen has replaced psychedelic as the name of choice and we may expect to see this trend continue.

Robin Carhart-HarrisandGuy Goodwinwrite that the termpsychedelicis preferable tohallucinogenfor describing classical psychedelics because of the termhallucinogen's "arguably misleading emphasis on these compounds' hallucinogenic properties."[31]

While the termpsychedelicis most commonly used to refer only to serotonergic hallucinogens,[11][10][32][33]it is sometimes used for a much broader range of drugs, includingempathogen–entactogens,dissociatives,and atypical hallucinogens/psychoactives such asAmanita muscaria,Cannabis sativa,Nymphaea nouchaliandSalvia divinorum.[22][34]Thus, the termserotonergic psychedelicis sometimes used for the narrower class.[35][36]It is important to check the definition of a given source.[30]This article uses the more common, narrower definition ofpsychedelic.

Examples[edit]

- 2C-B(2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromophenethylamine) is asubstituted phenethylaminefirst synthesised in 1974 byAlexander Shulgin.[37][page needed]2C-B is both a psychedelic and a mildentactogen,with its psychedelic effects increasing and its entactogenic effects decreasing with dosage. 2C-B is the most well known compound in the2C family,theirgeneral structurebeing discovered as a result of modifying the structure of mescaline.[37][page needed]

- DMT(N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is anindole alkaloidfound in various species of plants. Traditionally it is consumed by tribes in South America in the form ofayahuasca.A brew is used that consists of DMT-containing plants as well as plants containingMAOIs,specificallyharmaline,which allows DMT to be consumed orally without being rendered inactive bymonoamine oxidaseenzymes in the digestive system.[38]In the Western world DMT is more commonly consumed via the vaporisation of freebase DMT. Whereas Ayahuasca typically lasts for several hours, inhalation has an onset measured in seconds and has effects measured in minutes, being significantly more intense.[39]Particularly in vaporised form, DMT has the ability to cause users to enter a hallucinatory realm fully detached from reality, being typically characterised byhyperbolic geometry,and described as defying visual or verbal description.[40]Users have also reported encountering and communicating with entitites within this hallucinatory state.[41]DMT is the archetypalsubstituted tryptamine,being the structural scaffold of psilocybin and – to a lesser extent – the lysergamides.

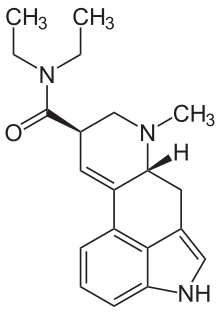

- LSD(Lysergic acid diethylamide) is a derivative oflysergic acid,which is obtained from thehydrolysisofergotamine.Ergotamine is analkaloidfound in the fungusClaviceps purpurea,which primarily infects rye. LSD is both the prototypical psychedelic and the prototypicallysergamide.As a lysergamide, LSD contains both atryptamineandphenethylaminegroup within its structure. As a result of containing a phenethylamine group LSDagonisesdopamine receptors as well as serotonin receptors,[42]making it more energetic in effect in contrast to the more sedating effects of psilocin, which is not a dopamine agonist.[43]

- Mescaline(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is aphenethylaminealkaloid found in various species of cacti, the best-known of these beingpeyote(Lophophora williamsii) and the San Pedro cactus (Trichocereus macrogonusvar.pachanoi,syn.Echinopsis pachanoi). Mescaline has effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin, albeit with a greater emphasis on colors and patterns.[44][page needed]Ceremonial San Pedro use seems to be characterized by relatively strong spiritual experiences, and low incidence of challenging experiences.[45]

- Psilocin(4-HO-DMT) is thedephosphorylatedactive metaboliteof theindole alkaloidpsilocybinand asubstituted tryptamine,which is produced inover 200 species of fungi.Of the Classical psychedelics psilocybin has attracted the greatest academic interest regarding its ability to manifest mystical experiences,[46]although all psychedelics are capable of doing so to variable degrees.O-Acetylpsilocin(4-AcO-DMT) is an acetylated analog of psilocin. Additionally, replacement of a methyl group at the dimethylatednitrogenwith an isopropyl or ethyl group yields4-HO-MIPTand4-HO-MET,respectively.[47]

Uses[edit]

Traditional[edit]

A number of frequently mentioned or traditional psychedelics such asAyahuasca(which containsDMT),San Pedro,Peyote,andPeruvian torch(which all containmescaline),Psilocybe mushrooms(which containpsilocin/psilocybin) andTabernanthe iboga(which contains the unique psychedelicibogaine) all have a long and extensive history ofspiritual,shamanicand traditional usage byindigenous peoplesin various world regions, particularly in Latin America, but alsoGabon,Africa in the case of iboga.[48]Different countries and/or regions have come to be associated with traditional or spiritual use of particular psychedelics, such as the ancient and entheogenic use of psilocybe mushrooms by the nativeMazatecpeople ofOaxaca,Mexico[49]or the use of the ayahuasca brew in theAmazon basin,particularly in Peru for spiritual and physical healing as well as for religious festivals.[50]Peyote has also been used for several thousand years in theRio Grande Valleyin North America by native tribes as anentheogen.[51]In theAndeanregion of South America, the San Pedro cactus (Trichocereus macrogonusvar.pachanoi,syn.Echinopsis pachanoi) has a long history of use, possibly as atraditional medicine.Archaeological studies have found evidence of use going back two thousand years, toMocheculture,[52]Nazca culture,[53]andChavín culture.Although authorities of theRoman Catholicchurch attempted to suppress its use after the Spanish conquest,[54]this failed, as shown by the Christian element in the common name "San Pedro cactus" –Saint Petercactus. The name has its origin in the belief that just as St Peter holds the keys to heaven, the effects of the cactus allow users "to reach heaven while still on earth."[55]In 2022, the Peruvian Ministry of Culture declared the traditional use of San Pedro cactus in northern Peru ascultural heritage.[56]

Although people ofWestern culturehave tended to use psychedelics for eitherpsychotherapeuticorrecreationalreasons, most indigenous cultures, particularly in South America, have seemingly tended to use psychedelics for moresupernaturalreasons such asdivination.This can often be related to "healing" or health as well but typically in the context of finding out what is wrong with the individual, such as using psychedelic states to "identify" a disease and/or its cause, locate lost objects, and identify a victim or even perpetrator ofsorcery.[57]In some cultures and regions, even psychedelics themselves, such as ayahuasca and the psychedeliclichenof eastern Ecuador (Dictyonema huaorani) that supposedly contains both5-MeO-DMTand psilocybin, have also been used by witches and sorcerers to conduct theirmalicious magic,similarly tonightshadedeliriantslikebrugmansiaandlatua.[57][citation needed]

Psychedelic therapy[edit]

Psychedelic therapy (or psychedelic-assisted therapy) is the proposed use of psychedelic drugs to treatmental disorders.[58]As of 2021, psychedelic drugs are controlled substances in most countries and psychedelic therapy is not legally available outside clinical trials, with some exceptions.[33][59]

The procedure for psychedelic therapy differs from that of therapies using conventionalpsychiatric medications.While conventional medications are usually taken without supervision at least once daily, in contemporary psychedelic therapy the drug is administered in a single session (or sometimes up to three sessions) in a therapeutic context.[60]The therapeutic team prepares the patient for the experience beforehand and helps them integrate insights from the drug experience afterwards.[61][62]After ingesting the drug, the patient normally wears eyeshades and listens to music to facilitate focus on the psychedelic experience, with the therapeutic team interrupting only to provide reassurance if adverse effects such as anxiety or disorientation arise.[61][62]

As of 2022, the body of high-quality evidence on psychedelic therapy remains relatively small and more, larger studies are needed to reliably show the effectiveness and safety of psychedelic therapy's various forms and applications.[21][22]On the basis of favorable early results, ongoing research is examining proposed psychedelic therapies for conditions includingmajor depressive disorder,[21][63]andanxietyand depression linked toterminal illness.[21][64]The United StatesFood and Drug Administrationhas granted "breakthrough therapy" status, which expedites the assessment of promising drug therapies for potential approval,[note 1]to psilocybin therapy for treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder.[33]

Recreational[edit]

Recreational use of psychedelics has been common since thepsychedelic eraof the mid-1960s and continues to play a role in various festivals and events, includingBurning Man.[16][17]A survey published in 2013 found that 13.4% of American adults had used a psychedelic.[66]

A June 2024 report by theRAND Corporationsuggests psilocybin mushrooms may be the most prevalent psychedelic drug among adults in the United States. The RAND national survey indicated that 3.1% of U.S. adults reported using psilocybin in the past year. Roughly 12% of respondents acknowledged lifetime use of psilocybin, while a similar percentage reported having usedLSDat some point in their lives.MDMA,also known as ecstasy, showed a lower prevalence of use at 7.6%. Notably, less than 1% of U.S. adults reported using any psychedelic drugs within the past month.[67]

Microdosing[edit]

Psychedelic microdosing is the practice of using sub-threshold doses (microdoses) of psychedelics in an attempt to improve creativity, boost physical energy level, emotional balance, increase performance on problems-solving tasks and to treat anxiety, depression and addiction.[68][69]The practice of microdosing has become more widespread in the 21st century with more people claiming long-term benefits from the practice.[70][71]

A 2022 study recognized signatures of psilocybin microdosing innatural languageand concluded that low amount of psychedelics have potential for application, and ecological observation of microdosing schedules.[72][73]

Pharmacology[edit]

While the method of action of psychedelics is not fully understood, they are known to show affinities for various 5-HT (serotonin) receptors in different ways and levels, and may be classified by their activity at different 5-HT sub-types, particularly 5-HT1A,5-HT2A,and 5-HT2C.[30]It is almost unanimously agreed that psychedelics produce their effect by acting as strong partialagonistsat the 5-HT2Areceptors.[2][9][10][11]How this produces the psychedelic experience is unclear, but it is likely that it acts by increasing excitation in the cortex, possibly by specifically facilitating input from thethalamus,the major relay for sensory information input to thecortex.[30][74]Additionally, researchers discovered that many psychedelics are potentpsychoplastogens,compounds capable of promoting rapid and sustainedneural plasticity.[75][76]

Tryptamines[edit]

Tryptamine,along with othertrace amines,is found in thecentral nervous systemofmammals.It is hypothesized to play a role as aneuromodulatoron classicalmonoamine neurotransmitters,such asdopamine,serotonin,norepinephrineandepinephrine.Tryptamine acts as a non-selectiveserotonin receptor agonistto activate serotonin receptors, and aserotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent(SNDRA) to release more monoamine neurotransmitter, with a preference for evoking serotonin and dopaminereleaseover norepinephrine (epinephrine) release.[77][78][79]Psychedelic tryptamines found in nature include psilocin,DMT,5-MeO-DMT, and tryptamines that have been synthesized in the laboratory include4-HO-MET,[80]4-HO-MiPT,[47]and5-MeO-DALT.[81]

Phenethylamines[edit]

Phenethylamineis also a trace amine but to a lesser extent acts as aneurotransmitterin the human central nervous system (CNS). Phenethylamine instead regulates monoamine neurotransmission by binding totrace amine-associated receptor 1(TAAR1), which plays a significant role in regulatingneurotransmissionin dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotoninneuronsin the CNS and inhibitingvesicular monoamine transporter 2(VMAT2) in monoamine neurons.[82][83]When VMAT2 is inhibited monoamine neurotransmitters such as dopamine cannot be released into the synapse via typical release mechanisms.[84]Mescaline is a naturally occurring psychedelicprotoalkaloidof thesubstituted phenethylamineclass.

Lysergamides[edit]

Amidesoflysergic acidare collectively known aslysergamides,and include a number of compounds with potent agonist and/or antagonist activity at various serotonin and dopaminereceptors.The structure of lysergamides contains the structure of both tryptamines and phenethylamines.LSD(Lysergic Acid Diethylamide) is one of many lysergamides. A wide range of lysergamides have emerged in recent years, inspired by existing scientific literature. Others, have appeared from chemical research.[85]1P-LSDis aderivativeandfunctional analogueof LSD and ahomologueofALD-52.It modifies the LSD molecule by adding apropionyl groupto the nitrogen atom of LSD'sindole.[86]

Psychedelic experiences[edit]

Although several attempts have been made, starting in the 19th and 20th centuries, to define commonphenomenologicalstructures of the effects produced by classic psychedelics, a universally accepted taxonomy does not yet exist.[87][88]At lower doses, features of psychedelic experiences include sensory alterations, such as the warping of surfaces, shape suggestibility, pareidolia and color variations. Users often report intense colors that they have not previously experienced, and repetitive geometric shapes orform constantsare common as well. Higher doses often cause intense and fundamental alterations of sensory (notablyvisual) perception, such assynesthesiaor the experience of additional spatial or temporal dimensions.[89]Tryptamines are well documented to cause classic psychedelic states, such as increasedempathy,visual distortions (drifting, morphing, breathing, melting of various surfaces and objects), auditory hallucinations, ego dissolution orego deathwith high enough dose, mystical,transpersonaland spiritual experiences, autonomous "entity"encounters, time distortion,closed eye hallucinationsand complete detachment from reality with a high enough dose.[90]Luis Lunadescribes psychedelic experiences as having a distinctlygnosis-like quality, and says that they offer "learning experiences that elevate consciousness and can make a profound contribution topersonal development."[91]Czech psychiatristStanislav Grofstudied the effects of psychedelics like LSD early in his career and said of the experience, that it commonly includes "complexrevelatoryinsightsinto the nature of existence… typically accompanied by a sense of certainty that this knowledge is ultimately more relevant and 'real' than the perceptions and beliefs we share in everyday life. "[citation needed]Traditionally, the standard model for thesubjectivephenomenological effects of psychedelics has typically been based on LSD, with anything that is considered "psychedelic" evidently being compared to it andits specific effects.[92]

During a speech on his 100th birthday, the inventor of LSD,Albert Hofmannsaid of the drug: "It gave me an inner joy, anopen mindedness,a gratefulness, open eyes and an internal sensitivity for the miracles of creation... I think that in human evolution it has never been as necessary to have this substance LSD. It is just a tool to turn us into what we are supposed to be. "[93]With certain psychedelics and experiences, a user may also experience an "afterglow"of improved mood or perceived mental state for days or even weeks after ingestion in some cases.[94]In 1898, the English writer and intellectualHavelock Ellisreported a heightened perceptual sensitivity to "the more delicate phenomena of light and shade and color" for a prolonged period of time after his exposure to mescaline.[95]Good trips are reportedly deeply pleasurable, and typically involve intense joy or euphoria, a greater appreciation for life, reduced anxiety, a sense of spiritual enlightenment, and a sense of belonging or interconnectedness with the universe.[96][97]Negative experiences, colloquially known as "bad trips," evoke an array of dark emotions, such as irrational fear, anxiety, panic, paranoia, dread, distrustfulness, hopelessness, and even suicidal ideation.[98]While it is impossible to predict when a bad trip will occur, one's mood, surroundings, sleep,hydration,social setting, and other factors can be controlled (colloquially referred to as "set and setting") to minimize the risk of a bad trip.[99][100]The concept of "set and setting" also generally appears to be more applicable to psychedelics than to other types of hallucinogens such as deliriants, hypnotics and dissociative anesthetics.[101]

Classic psychedelics are considered to be those found in nature like psilocybin, DMT, mescaline, and LSD which is derived from naturally occurring ergotamine, and non-classic psychedelics are considered to be newer analogs and derivatives of pharmacophore lysergamides, tryptamine, and phenethylamine structures like2C-B.Many of these psychedelics cause remarkably similar effects, despite their different chemical structure. However, many users report that the three major families have subjectively different qualities in the "feel" of the experience, which are difficult to describe. Some compounds, such as 2C-B, have extremely tight "dose curves", meaning the difference in dose between a non-event and an overwhelming disconnection from reality can be very slight. There can also be very substantial differences between the drugs; for instance, 5-MeO-DMT rarely produces the visual effects typical of other psychedelics.[11]

Potential adverse effects[edit]

Despite the contrary perception of much of the public, psychedelic drugs are not addictive and are physiologically safe.[18][19][11]As of 2016, there have been no known deaths due tooverdoseof LSD, psilocybin, or mescaline.[11]

Risks do exist during an unsupervised psychedelic experience, however;Ira Byockwrote in 2018 in theJournal of Palliative Medicinethat psilocybin is safe when administered to a properly screened patient and supervised by a qualified professional with appropriate set and setting. However, he called for an "abundance of caution" because in the absence of these conditions a range of negative reactions is possible, including "fear, a prolonged sense of dread, or full panic." He notes that driving or even walking in public can be dangerous during a psychedelic experience because of impairedhand-eye coordinationandfine motor control.[102]In some cases, individuals taking psychedelics have performed dangerous or fatal acts because they believed they possessed superhuman powers.[11]

Psilocybin-induced states of mind share features with states experienced inpsychosis,and while a causal relationship between psilocybin and the onset of psychosis has not been established as of 2011, researchers have called for investigation of the relationship.[103]Many of the persistent negative perceptions of psychological risks are unsupported by the currently available scientific evidence, with the majority of reported adverse effects not being observed in a regulated and/or medical context.[104]Apopulation studyon associations between psychedelic use and mental illness published in 2013 found no evidence that psychedelic use was associated with increased prevalence of any mental illness.[105]

Using psychedelics poses certain risks of re-experiencing of the drug's effects, including flashbacks andhallucinogen persisting perception disorder(HPPD).[103]These non-psychotic effects are poorly studied, but the permanent symptoms (also called "endless trip" ) are considered to be rare.[106]

Serotonin syndromecan be caused by combining psychedelics with other serotonergic drugs, including certain antidepressants, opioids, CNS stimulants (e.g. MDMA),5-HT1agonists (e.g.triptans), herbs and others.[107][108][109][110]

Potential therapeutic effects[edit]

Psychedelic substances which may have therapeutic uses include psilocybin, LSD, and mescaline.[23]During the 1950s and 1960s, lack ofinformed consentin some scientific trials on psychedelics led to significant, long-lasting harm to some participants.[23]Since then, research regarding the effectiveness of psychedelic therapy has been conducted under strict ethical guidelines, with fully informed consent and a pre-screening to avoid people with psychosis taking part.[23]Although the history behind these substances has hindered research into their potential medicinal value, scientists are now able to conduct studies and renew research that was halted in the 1970s. Some research has shown that these substances have helped people with such mental disorders asobsessive-compulsive disorder(OCD),post-traumatic stress disorder(PTSD), alcoholism, depression, andcluster headaches.[17]

It has long been known that psychedelics promote neurite growth andneuroplasticityand are potentpsychoplastogens.[111][112][113]There is evidence that psychedelics induce molecular and cellular adaptations related to neuroplasticity and that these could potentially underlie therapeutic benefits.[114][115]Psychedelics have also been shown to have potent anti-inflammatory activity and therapeutic effects in animal models of inflammatory diseases including asthma,[116]and cardiovascular disease and diabetes.[117]

Surrounding culture[edit]

Psychedelic culture includes manifestations such aspsychedelic music,[118]psychedelic art,[119]psychedelic literature,[120]psychedelic film,[121]and psychedelicfestivals.[122]Examples of psychedelic music would be rock bands like theGrateful Dead,Jefferson AirplaneandThe Beatles.Many psychedelic bands and elements of the psychedelic subculture originated in San Francisco during the mid to late 1960s.[123]

Legal status[edit]

Many psychedelics are classified under Schedule I of the United NationsConvention on Psychotropic Substancesof 1971 as drugs with the greatest potential to cause harm and no acceptable medical uses.[124]In addition, many countries have analogue laws; for example, in the United States, theFederal Analogue Actof 1986 automatically forbids any drugs sharing similar chemical structures or chemical formulas to illicit or prohibited substances if sold for human consumption.[125]

U.S. states such as Oregon and Colorado have also instituted decriminalization and legalization measures of psychedelics[126]and states like New Hampshire are attempting to do the same.[127]J.D. Tuccille argues that increasing rates of use of psychedelics in defiance of the law are likely to result in more widespread legalization and decriminalization of the substances in the United States (as has happened withalcoholandcannabis).[128]

See also[edit]

- Aztec use of entheogens

- Bwiti

- Cognitive liberty

- Concord Prison Experiment

- Designer Drugs

- Dissociative drug

- Deliriant

- Drug harmfulness

- Entheogenic drugs and the archaeological record

- Entheogenics and the Maya

- Hallucinogenic fish

- Hallucinogenic plants in Chinese herbals

- Hamilton's Pharmacopeia

- History of lysergic acid diethylamide

- Ibogaine

- List of designer drugs

- List of psychedelic drugs

- List of psychedelic plants

- Marsh Chapel Experiment

- Morning glory

- Mystical psychosis

- PiHKAL

- Psychedelia– Film about the history of psychedelic drugs

- Research chemical

- Serotonergic cell groups

- Serotonin syndrome

- Tabernanthe iboga

- TiHKAL

Categories[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^The Food and Drug Administration describes the designation of breakthrough therapy as "a process designed to expedite the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition and preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy on a clinically significant endpoint(s)."[65]

References[edit]

- ^"Peyote San Pedro Cactus – Shamanic Sacraments".D.M.Taylor.

- ^abcAghajanian, G (August 1999)."Serotonin and Hallucinogens".Neuropsychopharmacology.21(2): 16S–23S.doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00135-3.PMID10432484.

- ^abcMillière R, Carhart-Harris RL, Roseman L, Trautwein FM, Berkovich-Ohana A (2018)."Psychedelics, Meditation, and Self-Consciousness".Frontiers in Psychology.9:1475.doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01475.PMC6137697.PMID30245648.

- ^abMcClure-Begley TD, Roth BL (2022)."The promises and perils of psychedelic pharmacology for psychiatry".Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.21(6): 463–473.doi:10.1038/s41573-022-00421-7.PMID35301459.S2CID247521633.Retrieved2024-02-08.

- ^abcdTimmermann C, Roseman L, Williams L, Erritzoe D, Martial C, Cassol H, et al. (2018)."DMT Models the Near-Death Experience".Frontiers in Psychology.9:1424.doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01424.PMC6107838.PMID30174629.

- ^abR. R. Griffiths, W. A. Richards, U. McCann, R. Jesse (7 July 2006). "Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance".Psychopharmacology.187(3): 268–283.doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5.PMID16826400.S2CID7845214.

- ^McKenna, Terence (1992).Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human Evolution

- ^W. Davis (1996),One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest.New York, Simon and Schuster, Inc. p. 120.

- ^ab"Crystal Structure of LSD and 5-HT2AR Part 2: Binding Details and Future Psychedelic Research Paths".Psychedelic Science Review.2020-10-05.Retrieved2021-02-12.

- ^abcNichols DE (2018). "Chemistry and Structure–Activity Relationships of Psychedelics". In Halberstadt AL, Vollenweider FX, Nichols DE (eds.).Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs.Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 36. Berlin: Springer. pp. 1–43.doi:10.1007/7854_2017_475.ISBN978-3-662-55880-5.PMID28401524.

- ^abcdefghNichols DE (2016)."Psychedelics".Pharmacological Reviews.68(2): 264–355.doi:10.1124/pr.115.011478.ISSN0031-6997.PMC4813425.PMID26841800.

- ^Siegel GJ (11 November 2005).Basic neurochemistry: Molecular, cellular and medical aspects(7th ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.ISBN978-0-08-047207-2.OCLC123438340.

- ^Smigielski L, Scheidegger M, Kometer M, Vollenweider FX (August 2019)."Psilocybin-assisted mindfulness training modulates self-consciousness and brain default mode network connectivity with lasting effects".NeuroImage.196:207–215.doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.04.009.PMID30965131.S2CID102487343.

- ^abLetheby C, Gerrans P (2017)."Self unbound: ego dissolution in psychedelic experience".Neuroscience of Consciousness.3(1): nix016.doi:10.1093/nc/nix016.PMC6007152.PMID30042848.

The connection with findings about PCC deactivation in 'effortless awareness' meditation is obvious, and bolstered by the finding that acute ayahuasca intoxication increases mindfulness-related capacities.

- ^Brewer JA, Worhunsky PD, Gray JR, Tang YY, Weber J, Kober H (2011-12-13)."Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity".Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.108(50): 20254–20259.Bibcode:2011PNAS..10820254B.doi:10.1073/pnas.1112029108.PMC3250176.PMID22114193.

- ^abKrebs, Teri S, Johansen, Pål-Ørjan (28 March 2013)."Over 30 million psychedelic users in the United States".F1000Research.2:98.doi:10.12688/f1000research.2-98.v1.PMC3917651.PMID24627778.

- ^abcdGarcia-Romeu, Albert, Kersgaard, Brennan, Addy, Peter H. (August 2016)."Clinical applications of hallucinogens: A review".Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology.24(4): 229–268.doi:10.1037/pha0000084.PMC5001686.PMID27454674.

- ^abLe Dain G (1971).The Non-medical Use of Drugs: Interim Report of the Canadian Government's Commission of Inquiry.p. 106.

Physical dependence does not develop to LSD

- ^abLüscher, Christian, Ungless, Mark A. (14 November 2006)."The Mechanistic Classification of Addictive Drugs".PLOS Medicine.3(11): e437.doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030437.PMC1635740.PMID17105338.

- ^Rich Haridy (24 October 2018)."Psychedelic psilocybin therapy for depression granted Breakthrough Therapy status by FDA".newatlas.com.Retrieved2019-09-27.

- ^abcdBender D, Hellerstein DJ (2022). "Assessing the risk–benefit profile of classical psychedelics: a clinical review of second-wave psychedelic research".Psychopharmacology.239(6): 1907–1932.doi:10.1007/s00213-021-06049-6.PMID35022823.S2CID245906937.

- ^abcReiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, Carpenter LL, Widge AS, Rodriguez CI, et al. (May 2020). "Psychedelics and Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy".The American Journal of Psychiatry.177(5): 391–410.doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010035.PMID32098487.S2CID211524704.

- ^abcdTupper KW, Wood E, Yensen R, Johnson MW (2015-10-06)."Psychedelic medicine: a re-emerging therapeutic paradigm".CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal.187(14): 1054–1059.doi:10.1503/cmaj.141124.ISSN0820-3946.PMC4592297.PMID26350908.

- ^Orth T (July 28, 2022)."One in four Americans say they've tried at least one psychedelic drug".YouGov.

- ^Tanne JH (2004)."Humphrey Osmond".BMJ.328(7441): 713.doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7441.713.PMC381240.

- ^Oxford English Dictionary,3rd edition, September 2007,s.v.,Etymology

- ^A. Weil, W. Rosen. (1993),From Chocolate To Morphine: Everything You Need To Know About Mind-Altering Drugs.New York, Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 93

- ^W. Davis (1996), "One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest". New York, Simon and Schuster, Inc. p. 120.

- ^iia700700.us.archive.org

- ^abcdeNichols, David E. (2004). "Hallucinogens".Pharmacology & Therapeutics.101(2): 131–81.doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.002.PMID14761703.

- ^Carhart-Harris R,Guy G(2017)."The Therapeutic Potential of Psychedelic Drugs: Past, Present, and Future".Neuropsychopharmacology.42(11): 2105–2113.doi:10.1038/npp.2017.84.PMC5603818.PMID28443617.

- ^DiVito AJ, Leger RF (2020). "Psychedelics as an emerging novel intervention in the treatment of substance use disorder: a review".Molecular Biology Reports.47(12): 9791–9799.doi:10.1007/s11033-020-06009-x.PMID33231817.S2CID227157734.

- ^abcMarks M, Cohen IG (October 2021)."Psychedelic therapy: a roadmap for wider acceptance and utilization".Nature Medicine.27(10): 1669–1671.doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01530-3.PMID34608331.S2CID238355863.

- ^Siegel AN, Meshkat S, Benitah K, Lipstiz O, Gill H, Lui LM, et al. (2021). "Registered clinical studies investigating psychedelic drugs for psychiatric disorders".Journal of Psychiatric Research.139:71–81.doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.019.PMID34048997.S2CID235242044.

- ^Andersen KA, Carhart-Harris R, Nutt DJ, Erritzoe D (2020). "Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: A systematic review of modern-era clinical studies".Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.143(2): 101–118.doi:10.1111/acps.13249.PMID33125716.S2CID226217912.

- ^Malcolm B, Thomas K (2022). "Serotonin toxicity of serotonergic psychedelics".Psychopharmacology.239(6): 1881–1891.doi:10.1007/s00213-021-05876-x.PMID34251464.S2CID235796130.

- ^abShulgin AT (1991).Pihkal: a chemical love story.Ann Shulgin. Berkeley, CA: Transform Press.ISBN0-9630096-0-5.OCLC25627628.

- ^Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A, Barbanoj MJ (July 2003)."Human Pharmacology of Ayahuasca: Subjective and Cardiovascular Effects, Monoamine Metabolite Excretion, and Pharmacokinetics".Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics.306(1): 73–83.doi:10.1124/jpet.103.049882.ISSN0022-3565.PMID12660312.S2CID6147566.

- ^Haroz R, Greenberg MI (November 2005)."Emerging drugs of abuse".The Medical Clinics of North America.89(6): 1259–1276.doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2005.06.008.ISSN0025-7125.PMID16227062.

- ^Strassman RJ, Qualls CR, Uhlenhuth EH, Kellner R (1994-02-01)."Dose-Response Study of N,N-Dimethyltryptamine in Humans: II. Subjective Effects and Preliminary Results of a New Rating Scale".Archives of General Psychiatry.51(2): 98–108.doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950020022002.ISSN0003-990X.PMID8297217.

- ^Davis AK, Clifton JM, Weaver EG, Hurwitz ES, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR (September 2020)."Survey of entity encounter experiences occasioned by inhaled N,N -dimethyltryptamine: Phenomenology, interpretation, and enduring effects".Journal of Psychopharmacology.34(9): 1008–1020.doi:10.1177/0269881120916143.ISSN0269-8811.PMID32345112.

- ^Creese I, Burt DR, Snyder SH (1975-12-01)."The dopamine receptor: Differential binding of d-LSD and related agents to agonist and antagonist states".Life Sciences.17(11): 1715–1719.doi:10.1016/0024-3205(75)90118-6.ISSN0024-3205.PMID1207384.

- ^Passie T, Seifert J, Schneider U, Emrich HM (October 2002)."The pharmacology of psilocybin".Addiction Biology.7(4): 357–364.doi:10.1080/1355621021000005937.PMID14578010.S2CID12656091.

- ^Freye E (2009).Pharmacology and abuse of cocaine, amphetamines, ecstasy and related designer drugs: a comprehensive review on their mode of action, treatment of abuse and intoxication.Dordrecht: Springer.ISBN978-90-481-2448-0.OCLC489218895.

- ^Bohn A, Kiggen MH, Uthaug MV, van Oorsouw KI, Ramaekers JG, van Schie HT (2022-12-05)."Altered States of Consciousness During Ceremonial San Pedro Use".The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion.33(4): 309–331.doi:10.1080/10508619.2022.2139502.hdl:2066/285968.ISSN1050-8619.

- ^Griffiths RR, Richards WA, McCann U, Jesse R (August 2006)."Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance".Psychopharmacology.187(3): 268–283.doi:10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5.ISSN0033-3158.PMID16826400.S2CID7845214.

- ^ab"4-HO-MiPT".Psychedelic Science Review.2020-01-06.Retrieved2022-07-06.

- ^Carlini EA, Maia LO (2020)."Plant and Fungal Hallucinogens as Toxic and Therapeutic Agents".Plant Toxins.Toxinology. Springer Netherlands. pp. 1–44.doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6728-7_6-2.ISBN978-94-007-6728-7.S2CID239438352.Retrieved23 February2022.

- ^"History of Psychedelics: How the Mazatec Tribe Brought Entheogens to the World".Psychedelic Times.28 October 2015.Retrieved23 February2022.

- ^Ismael Eduardo Apud Peláez. (2020).Ayahuasca: Between Cognition and Culture.Publicacions Universitat Rovira i Virgili.ISBN978-84-8424-834-7.OCLC1229544084.

- ^Prince MA, O'Donnell MB, Stanley LR, Swaim RC (May 2019)."Examination of Recreational and Spiritual Peyote Use Among American Indian Youth".Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs.80(3): 366–370.doi:10.15288/jsad.2019.80.366.PMC6614926.PMID31250802.

- ^Bussmann RW, Sharon D (2006)."Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: tracking two thousand years of healing culture".J Ethnobiol Ethnomed.2(1): 47.doi:10.1186/1746-4269-2-47.PMC1637095.PMID17090303.

- ^Socha DM, Sykutera M, Orefici G (2022-12-01)."Use of psychoactive and stimulant plants on the south coast of Peru from the Early Intermediate to Late Intermediate Period".Journal of Archaeological Science.148:105688.Bibcode:2022JArSc.148j5688S.doi:10.1016/j.jas.2022.105688.ISSN0305-4403.S2CID252954052.

- ^Larco L (2008). "Archivo Arquidiocesano de Trujillo Sección Idolatrías. (Años 1768–1771)".Más allá de los encantos – Documentos sobre extirpación de idolatrías, Trujillo.Travaux de l'IFEA. Lima: IFEA Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. pp. 67–87.ISBN978-2-8218-4453-7.RetrievedApril 9,2020.

- ^Anderson EF (2001).The Cactus Family.Pentland, Oregon: Timber Press.ISBN978-0-88192-498-5.pp. 45–49.

- ^"Declaran Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación a los conocimientos, saberes y usos del cactus San Pedro".elperuano.pe(in Spanish). 2022-11-17.Retrieved2022-12-10.

- ^ab"Psychedelics Weren't As Common in Ancient Cultures As We Think".Vice Media.Vice. December 10, 2020.RetrievedJanuary 14,2023.

- ^Nutt D, Spriggs M, Erritzoe D (2023-02-01)."Psychedelics therapeutics: What we know, what we think, and what we need to research".Neuropharmacology.223:109257.doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109257.ISSN0028-3908.PMID36179919.

- ^Pilecki B, Luoma JB, Bathje GJ, Rhea J, Narloch VF (2021)."Ethical and legal issues in psychedelic harm reduction and integration therapy".Harm Reduction Journal.18(1): 40.doi:10.1186/s12954-021-00489-1.PMC8028769.PMID33827588.

- ^Nutt D, Erritzoe D, Carhart-Harris R (2020)."Psychedelic Psychiatry's Brave New World".Cell.181(1): 24–28.doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.020.PMID32243793.S2CID214753833.

- ^abJohnson MW, Richards WA, Griffiths RR (2008)."Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety".Journal of Psychopharmacology.22(6): 603–620.doi:10.1177/0269881108093587.PMC3056407.PMID18593734.

- ^abGarcia-Romeu A, Richards WA (2018). "Current perspectives on psychedelic therapy: use of serotonergic hallucinogens in clinical interventions".International Review of Psychiatry.30(4): 291–316.doi:10.1080/09540261.2018.1486289.ISSN0954-0261.PMID30422079.S2CID53291327.

- ^Romeo B, Karila L, Martelli C, Benyamina A (2020). "Efficacy of psychedelic treatments on depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis".Journal of Psychopharmacology.34(10): 1079–1085.doi:10.1177/0269881120919957.PMID32448048.S2CID218873949.

- ^Schimmel N, Breeksema JJ, Smith-Apeldoorn SY, Veraart J, van den Brink W, Schoevers RA (2022)."Psychedelics for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and existential distress in patients with a terminal illness: a systematic review".Psychopharmacology.239(15–33): 15–33.doi:10.1007/s00213-021-06027-y.PMID34812901.S2CID244490236.

- ^"Breakthrough Therapy".United States Food and Drug Administration. 1 April 2018. Archived fromthe originalon 1 March 2022.Retrieved27 March2022.

- ^Krebs, Teri S., Johansen, Pål-Ørjan (August 19, 2013)."Psychedelics and Mental Health: A Population Study".PLOS ONE.8(8): e63972.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...863972K.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063972.PMC3747247.PMID23976938.

- ^Goldman M (2024-06-27)."Mushrooms are the most commonly used psychedelic, study finds".Axios (website).Retrieved2024-06-28.

- ^Fadiman J (2016-01-01)."Microdose research: without approvals, control groups, double blinds, staff or funding".Psychedelic Press.XV.

- ^Brodwin E (30 January 2017)."The truth about 'microdosing,' which involves taking tiny amounts of psychedelics like LSD".Business Insider.Retrieved19 April2017.

- ^Dahl H (7 July 2015)."A Brief History of LSD in the Twenty-First Century".Psychedelic Press UK.Retrieved19 April2017.

- ^Webb M, Copes H, Hendricks PS (August 2019). "Narrative identity, rationality, and microdosing classic psychedelics".The International Journal on Drug Policy.70:33–39.doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.04.013.PMID31071597.S2CID149445841.

- ^Chemistry Uo, Prague T."Recognizing signatures of psilocybin microdosing in natural language".medicalxpress.com.Retrieved2022-10-03.

- ^Sanz C, Cavanna F, Muller S, de la Fuente L, Zamberlan F, Palmucci M, et al. (2022-09-01)."Natural language signatures of psilocybin microdosing".Psychopharmacology.239(9): 2841–2852.doi:10.1007/s00213-022-06170-0.ISSN1432-2072.PMID35676541.S2CID247067976.

- ^Dolan EW (2023-06-02)."Neuroscience research sheds light on how LSD alters the brain's" gatekeeper "".Psypost - Psychology News.Retrieved2023-06-02.

- ^Ly C, Greb AC, Cameron LP, Wong JM, Barragan EV, Wilson PC, et al. (2018)."Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity".Cell Reports.23(11): 3170–3182.doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.022.PMC6082376.PMID29898390.

- ^Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, et al. (2023-02-17)."Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors".Science.379(6633): 700–706.Bibcode:2023Sci...379..700V.doi:10.1126/science.adf0435.ISSN0036-8075.PMC10108900.PMID36795823.

- ^Wölfel R, Graefe KH (February 1992). "Evidence for various tryptamines and related compounds acting as substrates of the platelet 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter".Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology.345(2): 129–136.doi:10.1007/BF00165727.ISSN0028-1298.PMID1570019.S2CID2984583.

- ^Shimazu S, Miklya I (May 2004). "Pharmacological studies with endogenous enhancer substances: β-phenylethylamine, tryptamine, and their synthetic derivatives".Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry.28(3): 421–427.doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.016.PMID15093948.S2CID37564231.

- ^Blough BE, Landavazo A, Partilla JS, Baumann MH, Decker AM, Page KM, et al. (2014-06-12)."Hybrid Dopamine Uptake Blocker–Serotonin Releaser Ligands: A New Twist on Transporter-Focused Therapeutics".ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters.5(6): 623–627.doi:10.1021/ml500113s.ISSN1948-5875.PMC4060932.PMID24944732.

- ^"4-HO-MET".The Drug Classroom.Retrieved2022-07-31.

- ^Shulgin, Alexander T. (Alexander Theodore) (1997).Tihkal: the continuation.Shulgin, Ann. (1st ed.). Berkeley, CA: Transform Press.ISBN0-9630096-9-9.OCLC38503252.

- ^Miller GM (2010-12-16)."The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity".Journal of Neurochemistry.116(2): 164–176.doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x.ISSN0022-3042.PMC3005101.PMID21073468.

- ^Grandy G (2020-04-23)."Guest editorial".Gender in Management.35(3): 257–260.doi:10.1108/GM-05-2020-238.ISSN1754-2413.

- ^Little KY, Krolewski DM, Zhang L, Cassin BJ (January 2003). "Loss of Striatal Vesicular Monoamine Transporter Protein (VMAT2) in Human Cocaine Users".American Journal of Psychiatry.160(1): 47–55.doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.47.ISSN0002-953X.PMID12505801.

- ^Brandt SD, Kavanagh PV, Westphal F, Stratford A, Odland AU, Klein AK, et al. (2020-04-20)."Return of the lysergamides. Part VI: Analytical and behavioural characterization of 1-cyclopropanoyl- d -lysergic acid diethylamide (1CP-LSD)"(PDF).Drug Testing and Analysis.12(6): 812–826.doi:10.1002/dta.2789.ISSN1942-7603.PMC9191646.PMID32180350.S2CID212738912.

- ^Grumann C, Henkel K, Brandt SD, Stratford A, Passie T, Auwärter V (2020)."Pharmacokinetics and subjective effects of 1P-LSD in humans after oral and intravenous administration".Drug Testing and Analysis.12(8): 1144–1153.doi:10.1002/dta.2821.ISSN1942-7611.PMID32415750.

- ^Preller KH, Vollenweider FX (2016). "Phenomenology, Structure, and Dynamic of Psychedelic States". In Adam L. Halberstadt, Franz X. Vollenweider, David E. Nichols (eds.).Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs.Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 36. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 221–256.doi:10.1007/7854_2016_459.ISBN978-3-662-55878-2.PMID28025814.

- ^Swanson LR (2018-03-02)."Unifying Theories of Psychedelic Drug Effects".Frontiers in Pharmacology.9:172.doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00172.ISSN1663-9812.PMC5853825.PMID29568270.

- ^Luke, David (28 November 2013). "Rock Art or Rorschach: Is there More to Entoptics than Meets the Eye?".Time and Mind.3(1): 9–28.doi:10.2752/175169710x12549020810371.S2CID144948636.

- ^Berry MD (July 2004)."Mammalian central nervous system trace amines. Pharmacologic amphetamines, physiologic neuromodulators".Journal of Neurochemistry.90(2): 257–271.doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02501.x.ISSN0022-3042.PMID15228583.S2CID12126296.

- ^Luna LE (1984)."The concept of plants as teachers among four mestizo shamans of Iquitos, northeastern Peru"(PDF).Journal of Ethnopharmacology.11(2): 135–156.doi:10.1016/0378-8741(84)90036-9.PMID6492831.Retrieved10 July2020.

- ^Nichols DE (April 2016)."Psychedelics".Pharmacological Reviews.68(2): 264–355.doi:10.1124/pr.115.011478.PMC4813425.PMID26841800.

- ^"LSD: The Geek's Wonder Drug?".Wired.16 January 2006.Retrieved29 April2008.

- ^Majić T, Schmidt TT, Gallinat J (March 2015). "Peak experiences and the afterglow phenomenon: when and how do therapeutic effects of hallucinogens depend on psychedelic experiences?".Journal of Psychopharmacology.29(3): 241–53.doi:10.1177/0269881114568040.PMID25670401.S2CID16483172.

- ^Hanson D (29 April 2013)."When the Trip Never Ends".Dana Foundation.

- ^Honig D."Frequently Asked Questions".Erowid.Archived fromthe originalon 12 February 2016.

- ^McGlothlin W, Cohen S, McGlothlin MS (November 1967)."Long lasting effects of LSD on normals"(PDF).Archives of General Psychiatry.17(5): 521–32.doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1967.01730290009002.PMID6054248.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on April 30, 2011.

- ^Canadian government (1996)."Controlled Drugs and Substances Act".Justice Laws.Canadian Department of Justice. Archived fromthe originalon December 15, 2013.RetrievedDecember 15,2013.

- ^Rogge T (May 21, 2014),Substance use – LSD,MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine,archivedfrom the original on July 28, 2016,retrievedJuly 14,2016

- ^CESAR (29 October 2013),LSD,Center for Substance Abuse Research, University of Maryland, archived fromthe originalon July 15, 2016,retrieved14 July2016

- ^Garcia-Romeu A, Kersgaard B, Addy PH (August 2016)."Clinical applications of hallucinogens: A review".Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology.24(4): 229–268.doi:10.1037/pha0000084.PMC5001686.PMID27454674.

- ^Byock I(2018)."Taking Psychedelics Seriously".Journal of Palliative Medicine.21(4): 417–421.doi:10.1089/jpm.2017.0684.PMC5867510.PMID29356590.

- ^abvan Amsterdam J, Opperhuizen A, van den Brink W (2011). "Harm potential of magic mushroom use: A review".Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology.59(3): 423–429.doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.01.006.PMID21256914.

- ^Schlag AK, Aday J, Salam I, Neill JC, Nutt DJ (2022-02-02)."Adverse effects of psychedelics: From anecdotes and misinformation to systematic science".Journal of Psychopharmacology.36(3): 258–272.doi:10.1177/02698811211069100.ISSN0269-8811.PMC8905125.PMID35107059.

- ^Krebs, Teri S., Johansen, Pål-Ørjan, Lu, Lin (19 August 2013)."Psychedelics and Mental Health: A Population Study".PLOS ONE.8(8): e63972.Bibcode:2013PLoSO...863972K.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063972.PMC3747247.PMID23976938.

- ^Baggott MJ, Coyle JR, Erowid E, Erowid F, Robertson LC (1 March 2011). "Abnormal visual experiences in individuals with histories of hallucinogen use: A web-based questionnaire".Drug and Alcohol Dependence.114(1): 61–67.doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.006.PMID21035275.

- ^Bijl D (October 2004). "The serotonin syndrome".Neth J Med.62(9): 309–13.PMID15635814.

Mechanisms of serotonergic drugs implicated in serotonin syndrome... Stimulation of serotonin receptors... LSD

- ^"AMT".DrugWise.org.uk.2016-01-03.Retrieved2019-11-18.

- ^Alpha-methyltryptamine (AMT) – Critical Review Report(PDF)(Report). World Health Organisation – Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (published 2014-06-20). 20 June 2014.Retrieved2019-11-18.

- ^Boyer EW,Shannon M(March 2005)."The serotonin syndrome"(PDF).The New England Journal of Medicine.352(11): 1112–20.doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867.PMID15784664.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2013-06-18.

- ^Jones K, Srivastave D, Allen J, Roth B, Penzes P (2009)."Psychedelics Promote Structural and Functional Neural Plasticity".Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.106(46): 19575–19580.doi:10.1073/pnas.0905884106.PMC2780750.PMID19889983.

- ^Yoshida H, Kanamaru C, Ohtani A, Senzaki K, Shiga T (2011)."Subtype specific roles of serotonin receptors in the spine formation of cortical neurons in vitro"(PDF).Neurosci Res.71(3): 311–314.doi:10.1016/j.neures.2011.07.1824.hdl:2241/114624.PMID21802453.S2CID14178672.

- ^Ly C, Greb AC, Cameron LP, Wong JM, Barragan EV, Wilson PC, et al. (June 2018)."Psychedelics Promote Structural and Functional Neural Plasticity".Cell Reports.23(11): 3170–3182.doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.022.PMC6082376.PMID29898390.

- ^de Vos CM, Mason NL, Kuypers KP (2021)."Psychedelics and Neuroplasticity: A Systematic Review Unraveling the Biological Underpinnings of Psychedelics".Frontiers in Psychiatry.12:1575.doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724606.ISSN1664-0640.PMC8461007.PMID34566723.

- ^Calder AE, Hasler G (2022-09-19)."Towards an understanding of psychedelic-induced neuroplasticity".Neuropsychopharmacology.48(1): 104–112.doi:10.1038/s41386-022-01389-z.ISSN1740-634X.PMC9700802.PMID36123427.S2CID252381170.

- ^Nau F, Miller J, Saravia J, Ahlert T, Yu B, Happel K, et al. (2015)."Serotonin 5-HT₂ receptor activation prevents allergic asthma in a mouse model".American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology.308(2): 191–198.doi:10.1152/ajplung.00138.2013.PMC4338939.PMID25416380.

- ^Flanagan T, Sebastian M, Battaglia D, Foster T, Maillet E, Nichols C (2019)."Activation of 5-HT2 Receptors Reduces Inflammation in Vascular Tissue and Cholesterol Levels in High-Fat Diet-Fed Apolipoprotein E Knockout Mice".Sci. Rep.9(1): 13444–198.Bibcode:2019NatSR...913444F.doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49987-0.PMC6748996.PMID31530895.

- ^Hicks M (15 January 2000).Sixties Rock: Garage, Psychedelic, and Other Satisfactions.Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 63–64.ISBN0-252-06915-3.

- ^Krippner S (2017). "Ecstatic Landscapes: The Manifestation of Psychedelic Art".Journal of Humanistic Psychology.57(4): 415–435.doi:10.1177/0022167816671579.S2CID151517152.

- ^Dickins R (2013)."Preparing the Gaia connection: An ecological exposition of psychedelic literature 1954-1963".European Journal of Ecopsychology.4:9–18.CiteSeerX10.1.1.854.6673.Retrieved7 January2021.

- ^Gallagher M (2004). "Tripped Out: The Psychedelic Film and Masculinity".Quarterly Review of Film and Video.21(3): 161–171.doi:10.1080/10509200490437817.S2CID191583864.

- ^St John, Graham."Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival."Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture,1(1) (2009).

- ^Hirschfelder A (Jan 14, 2016)."The Trips Festival explained".Experiments in Environment: The Halprin Workshops, 1966–1971.

- ^Rucker JJ (2015). "Psychedelic drugs should be legally reclassified so that researchers can investigate their therapeutic potential".British Medical Journal.350:h2902.doi:10.1136/bmj.h2902.PMID26014506.S2CID46510541.

- ^"U.S.C. Title 21 – FOOD AND DRUGS".www.govinfo.gov.Retrieved28 February2022.

- ^"Pot Prohibition Continues Collapsing, and Psychedelic Bans Could Be Next".November 9, 2022.

- ^"New Hampshire Lawmakers File Psilocybin And Broader Drug Decriminalization Bills For 2022".December 29, 2021.

- ^Tuccille J (3 August 2022)."Scofflaws Lead the Way To Legalizing Psychedelic Drugs".Reason.Retrieved18 January2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Echard W (2017).Psychedelic Popular Music: A History through Musical Topic Theory.Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.doi:10.2307/j.ctt1zxxzgx.ISBN978-0-253-02645-3.

- Halberstadt AL, Franz X. Vollenweider, David E. Nichols, eds. (2018).Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs.Vol. 36. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.ISBN978-3-662-55878-2.

- Jay M (2019).Mescaline: A Global History of the First Psychedelic.New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.doi:10.2307/j.ctvgc61q9.ISBN978-0-300-25750-2.S2CID241952235.

- Letheby C (2021).Philosophy of Psychedelics.Oxford: Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/med/9780198843122.001.0001.ISBN978-0-19-884312-2.

- Richards WA (2016).Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experiences.New York: Columbia University Press.ISBN978-0-231-54091-9.

- Siff S (2015).Acid Hype: American News Media and the Psychedelic Experience.Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.ISBN978-0-252-09723-2.

- Winstock, Ar; Timmerman, C; Davies, E; Maier, Lj; Zhuparris, A; Ferris, Ja; Barratt, Mj; Kuypers, Kpc (2021).Global Drug Survey (GDS) 2020 Psychedelics Key Findings Report.

External links[edit]

Psychedelic Timelineby Tom Frame, Psychedelic Times