Rawson Stovall

Rawson Stovall | |

|---|---|

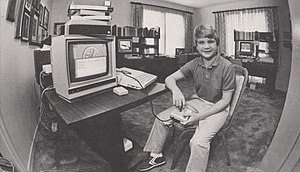

Stovall in 1985, aged thirteen[1] | |

| Born | Rawson Law Stovall 1972 (age 51–52) Abilene, Texas,U.S. |

| Alma mater | Southern Methodist University |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1982–present |

| Known for | Becoming the first nationallysyndicatedgaming journalistin the U.S. |

| Notable work | The Vid Kid's Book of Home Video Games(1984) |

Rawson Law Stovall(born 1972)[a]is an Americanvideo game designerand producer. He started out as avideo game journalist,the first to be nationallysyndicatedin the United States.[4]In 1982, ten-year-old Stovall's first column appeared in theAbilene Reporter-News,his local newspaper. He got the column in ten publications beforeUniversal Press Syndicatestarted distributing it in April 1983; by 1984, the column, titled "The Vid Kid", appeared in over twenty-four newspapers. After being reported on byThe New York Times,Stovall was featured onThe Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carsonand earned a regular spot onDiscovery Channel'sThe New Tech Times.In 1985, he helped introduce theNintendo Entertainment Systemat its North American launch.

In 1990, Stovall retired from video game journalism to attendSouthern Methodist University.He later worked as a game designer and producer forSony,Activision,Electronic Arts,MGM Interactive,and most recentlyConcrete Software.At Electronic Arts, he produced video games inThe Simsfranchise.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Rawson Law Stovall[5]was born in 1972[a]to Ronald L. Stovall, a regional manager for theTexas State Health Departmentand formerBoy Scoutsexecutive; and Kay Law Stovall.[3][6]He has a younger sister named Jennifer.[2]During his childhood, Stovall lived inAbilene, Texas,where he attended Alta Vista Elementary School andCooper High School.[5][7]As a child, he had severeasthmaand once spent three months at theNational Jewish Hospital:he first visited anamusement arcadeon one of the hospital's field trips.[7][8]

Stovall first became interested in arcade video games in 1978.[6]He rented games from the Abilene Video Library, allowing him to study the elements and patterns used by different genres and developers.[7]However, his father saw games as a waste of time and refused to buy him anAtari 2600.After Stovall failed to get an Atari for Christmas in 1980, he prepared and packaged nuts from thepecantree in his backyard and sold them door-to-door the next year, earning enough to buy one.[3][5][b]In fourth grade, Stovall and two friends hosted mock television skits about video games for class.[3][9]He also became the youngest person to receive the Texas Governor's Award for Outstanding Volunteer Service after he raised over $5000 for Abilene's mental health association.[10]

1982: Beginnings as a columnist

[edit]In the summer of 1981, Stovall was confined indoors because his asthma was triggered by the increasedpollen levels,and he could not afford more games.[3]He realized that, unlike reviews for movie and television shows, nothing similar existed for games. At the time, a movie ticket cost less than $5, while a game might cost $30–40. Video-game packaging did not consistently include screenshots. The expense and the lack of information available to consumers led Stovall to compare buying video games to a "gamble".[4][8]Stovall's mother suggested he write an article about video games for theWylie Journal,a local weekly. Stovall thought the weekly was too small and an article would be too short, so she instead proposed that he write a column for his city newspaper, theAbilene Reporter-News.[6][9]He decided to do so initially to raise enough money to buy an advanced home computer on which to design games.[11]

Stovall contacted theReporter-News' editor Dick Tarpley, to whom he presented several sample columns and three letters of recommendation from his teachers and a local video-game repairman. Two days later, Tarpley offered him a weekly place in the paper for $5 per column.[2]In 1982, a ten-year-old Stovall's first column, "Video Beat", appeared in theReporter-News.[7]

Stovall attempted to sell his column to other newspapers, but was often turned down because of his age: the guard at theSan Francisco Chroniclewould not even let him into the building.[6][11]After several rejections by telephone, Stovall decided to enter the offices ofOdessa Americanwearing a three-piece business suit, and carrying a briefcase and a business card. He persuaded the editor to publish his column, securing his first sale outside Abilene.[3]

1983–1990: Universal Press Syndicate and "The Vid Kid"

[edit]By January 1983, Rawson Stovall's column appeared in five newspapers,[5]includingEl Paso TimesandYoung Person Magazine.[12]His mother acted as his secretary and proofread his work,[5]while his father, a journalism major, offered advice.[7]Stovall was invited to video game publisherImagic's headquarters inSilicon Valleyand went on a promotional nationwide tour with their vice president Dennis Koble.[5]San Jose Mercury Newsbegan syndicating the column and dubbed it "The Vid Kid". Stovall's column ran in ten papers beforeUniversal Press Syndicatebegan distributing it in April 1983 at the suggestion ofMercury News' editor.[6][9]This made the eleven-year-old Stovall the first nationally syndicated video-game journalist.[4]

Stovall was given special permission to attend the 1983Consumer Electronics Show(CES) inChicagoas a minor, where he interviewedNolan BushnellandDavid Crane.After a reporter at the event covered him inThe New York Times,[4][6]he was invited to appear on television shows such asCBS Morning News,Good Morning America,NBC Nightly NewsandThat's Incredible!and the radio programThe Rest of the Story.[10]He attended CES in following years and was consulted by industry professionals and companies, includingActivisionpresidentJim Levy.[2]He was later featured on the front page ofThe Wall Street Journal.[7]

By 1984, Stovall's columns appeared in over twenty-four newspapers, and he charged $10 per column.[3][9]That year, Stovall spoke atBits & Bytes,the first computer trade show for children, andDoubledaypublishedThe Vid Kid's Book of Home Video Games,a compilation of his reviews. ALibrary Journalreviewer wrote that, while Stovall's age and writing style made the book unusual, it was average overall.[4][13]Stovall and Universal Press Syndicate ended their contract later in the year by mutual agreement, but his column continued to run in theReporter-News.[10]

In 1985, Stovall began to lighten his schedule to make more time for school.[2]His family visitedLos Angelesfor two weeks for his July 23 appearance onThe Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.[7][10]Stovall helped to introduce theNintendo Entertainment Systemat its North American launch,[4][8]and also began reviewing teenage-oriented software and games for his regular segment on theDiscovery ChannelshowThe New Tech Times,for which the channel paid him $850 each season.[3][12]By this time, his workshop contained over six hundred video games and five computers.[2]

Adults credited Stovall's success to his maturity and gregariousness. His mother described him as a flexible personality: "When he was with kids, he was a kid. But with grown-ups, he was mature."[7]Executive producer Jeff Clark, who worked with Stovall onThe New Tech Times,said that Stovall had the "business ability and vocabulary of a 40-year-old, but the mind-set of a thirteen-year-old".[14]In 2009, Stovall reflected that although it was sometimes difficult to balance school, journalism and his health issues, he felt his experience in journalism was a beneficial one.[7]

Later career and personal life

[edit]Stovall retired from journalism in 1990 to attendSouthern Methodist UniversityinDallas.[8]He graduated with a degree in cinema due to the lack of game-related degrees. After college, Stovall moved to Los Angeles, and worked atSony,Activision,Electronic Arts(EA), andMGM Interactive.[4][7]At Activision in the 1990s, he worked as a game developer and producer.[7][15]At EA, he producedThe Godfather(2006), and video games in franchisesMedal of HonorandThe Sims.[7]As of 2022[update],he works as a senior designer onmobile gamesforConcrete Software,which hired him in 2014.[4][16]

Stovall currently lives in the area ofMinneapolis–Saint Paul.[17]He previously lived inRedwood City, California.[18]He is married to Jenn Marshall, who teaches art history at theUniversity of Minnesota,with whom he has one son.[7][19]

Bibliography

[edit]- Stovall, Rawson (1984).The Vid Kid's Book of Home Video Games.Garden City, New York:Doubleday.ISBN9780385193092.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^abStovall was thirteen in June 1985[2]and fourteen in January 1987,[3]placing his birth in 1972.

- ^As noted byAbilene Reporter-News,sources disagree on the amount Stovall earned. While estimates range around $175 to $200, Stovall said in 2011 it was around $160.[7]Most recently,PC Gamersaid he earned $220 in 2022.[4]

References

[edit]- ^"Rawson Stovall —A Success At Only 13".Brøderbund Newsletter.August 1985. p. 4 – viaInternet Archive.

- ^abcdefMiller, M.W. (June 18, 1985). "Rawson Stovall, 13, Has a Giant Industry Seeking His Wisdom".The Wall Street Journal.Vol. 205, no. 118.Dow Jones & Company.p. 1.ISSN0099-9660.

- ^abcdefghMonroe, Keith(January 1987)."He Turned Computer Games To Gold".Boys' Life.Vol. 77, no. 1.Boy Scouts of America.pp. 14–15.ISSN0006-8608– viaGoogle Books.

- ^abcdefghiOng, Alexis (August 2, 2022)."The world's first syndicated game journalist was an 11-year-old kid".PC Gamer.Future plc.RetrievedNovember 11,2022.

- ^abcdefAdamo, Sue (January 1983). Bloom, Steve (ed.)."Who'll Stop Rawson Stovall?".Video Games.Vol. 1, no. 4. Pumpkin Press. pp. 14, 19 – viaInternet Archive.

- ^abcdef"Youth's Column Makes Him Popular With the Top Minds in Video Games".The New York Times.June 8, 1983. p. 14.ISSN0362-4331.RetrievedNovember 11,2022.

- ^abcdefghijklmnBethel, Brian (October 3, 2009)."The Vid Kid: Stovall was game review trailblazer".Abilene Reporter-News.Gannett Media Corp.p. 1.ISSN0199-3267.Archived fromthe originalon December 8, 2009.

- ^abcdPatterson, Patrick Scott (April 17, 2015)."Icons: Rawson Stovall is the original video game critic".Syfy Games.Archived fromthe originalon April 29, 2015.

- ^abcdStoler, Peter (1984).The Computer Generation.New York, New York: Facts on File Publications. pp. 111–112.ISBN9780871968319– viaInternet Archive.

- ^abcdConley, Jim (September 15, 1985). Schoch, Philip (ed.). "At 13, Rawson Stovall is a businessman, author and celebrity".Texas Weekly Magazine.Vol. 1, no. 2. TWM, Inc.,Harte-Hanks Magazines.pp. 8, 9.

- ^abKastor, Elizabeth (August 13, 1983)."Calling the Plays".The Washington Post.RetrievedNovember 21,2022.

- ^abPoulos, Cynthia; Hoffer, William (November 1985). "The business whiz kids".Nation's Business.Vol. 73.U.S. Chamber of Commerce.p. 25.ISSN0028-047X.

- ^Oakley, Jack (November 1, 1984). "Stovall, Rawson. The VID Kid's Book of Home Video Games".Library Journal.Vol. 109, no. 18. p. 2076.ISSN0363-0277.

- ^"News in Brief".PCMag.Vol. 4, no. 6.Ziff Davis.March 19, 1985. p. 42.ISSN0888-8507– viaGoogle Books.

- ^Colker, David (January 10, 1995)."Vintage Video Games: The Latest Blip: Computer Game Producers Look Back to the Past for New Hits at Electronics Show".Los Angeles Times.Vol. 114.ISSN0458-3035.RetrievedNovember 12,2022.

- ^"Concrete Software Hires Veteran Game Designer – Rawson Stovall".Concrete Software.September 5, 2014.RetrievedNovember 11,2022.

- ^Stovall, Rawson."@rawsonstovall".Twitter.RetrievedNovember 21,2022.

- ^"94"(PDF).Class Notes.SMU Magazine.Southern Methodist University.Fall–Winter 2008. p. 44.

Rawson Stovall is a producer at Electronic Arts, a video game publisher in California. He lives in Redwood City.

- ^"Kay Law Stovall Obituary".Legacy.com.March 15, 2023.RetrievedJune 29,2023.