Dominance (genetics)

This articleneeds additional citations forverification.(February 2018) |

Ingenetics,dominanceis the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of ageneon achromosomemasking or overriding theeffectof a different variant of the same gene onthe other copy of the chromosome.[1][2]The first variant is termeddominantand the second is calledrecessive.This state of havingtwo different variantsof the same gene on each chromosome is originally caused by amutationin one of the genes, either new (de novo) orinherited.The termsautosomal dominantorautosomal recessiveare used to describe gene variants on non-sex chromosomes (autosomes) and their associated traits, while those onsex chromosomes(allosomes) are termedX-linked dominant,X-linked recessiveorY-linked;these have an inheritance and presentation pattern that depends on the sex of both the parent and the child (seeSex linkage). Since there is only one copy of theY chromosome,Y-linked traits cannot be dominant or recessive.[3]Additionally, there are other forms of dominance, such asincomplete dominance,in which a gene variant has a partial effect compared to when it is present on both chromosomes, andco-dominance,in which different variants on each chromosome both show their associated traits.

Dominance is a key concept inMendelian inheritanceandclassical genetics.Letters andPunnett squaresare used to demonstrate the principles of dominance in teaching, and the upper-case letters are used to denote dominant alleles and lower-case letters are used for recessive alleles. An often quoted example of dominance is the inheritance ofseedshape inpeas.Peas may be round, associated with alleleR,or wrinkled, associated with alleler.In this case, three combinations of alleles (genotypes) are possible:RR,Rr,andrr.TheRR(homozygous) individuals have round peas, and therr(homozygous) individuals have wrinkled peas. InRr(heterozygous) individuals, theRallele masks the presence of therallele, so these individuals also have round peas. Thus, alleleRis dominant over alleler,and alleleris recessive to alleleR.[4]

Dominance is not inherent to an allele or its traits (phenotype). It is a strictly relative effect between two alleles of a given gene of any function; one allele can be dominant over a second allele of the same gene, recessive to a third, andco-dominantwith a fourth. Additionally, one allele may be dominant for one trait but not others.[5]Dominance differs fromepistasis,the phenomenon of an allele of one gene masking the effect of alleles of adifferentgene.[6]

Background

[edit]

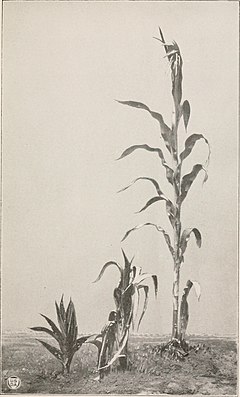

Gregor Johann Mendel,"The Father of Genetics", promulgated the idea of dominance in the 1860s. However, it was not widely known until the early twentieth century. Mendel observed that, for a variety of traits of garden peas having to do with the appearance of seeds, seed pods, and plants, there were two discrete phenotypes, such as round versus wrinkled seeds, yellow versus green seeds, red versus white flowers or tall versus short plants. When bred separately, the plants always produced the same phenotypes, generation after generation. However, when lines with different phenotypes were crossed (interbred), one and only one of the parental phenotypes showed up in the offspring (green, round, red, or tall). However, when thesehybridplants were crossed, the offspring plants showed the two original phenotypes, in a characteristic 3:1 ratio, the more common phenotype being that of the parental hybrid plants. Mendel reasoned that each parent in the first cross was a homozygote for different alleles (one parent AA and the other parent aa), that each contributed one allele to the offspring, with the result that all of these hybrids were heterozygotes (Aa), and that one of the two alleles in the hybrid cross dominated expression of the other: A masked a. The final cross between two heterozygotes (Aa X Aa) would produce AA, Aa, and aa offspring in a 1:2:1 genotype ratio with the first two classes showing the (A) phenotype, and the last showing the (a) phenotype, thereby producing the 3:1 phenotype ratio.

Mendel did not use the terms gene, allele, phenotype, genotype, homozygote, and heterozygote, all of which were introduced later. He did introduce the notation of capital and lowercase letters for dominant and recessive alleles, respectively, still in use today.

In 1928, British population geneticistRonald Fisherproposed that dominance acted based on natural selection through the contribution ofmodifier genes.In 1929, American geneticistSewall Wrightresponded by stating that dominance is simply a physiological consequence of metabolic pathways and the relative necessity of the gene involved.[7][8][9][5]

Types of dominance

[edit]Complete dominance (Mendelian)

[edit]In complete dominance, the effect of one allele in a heterozygous genotype completely masks the effect of the other. The allele that masks are considereddominantto the other allele, and the masked allele is consideredrecessive.[10]

When we only look at one trait determined by one pair of genes, we call itmonohybrid inheritance.If the crossing is done between parents (P-generation, F0-generation) who are homozygote dominant and homozygote recessive, the offspring (F1-generation) will always have the heterozygote genotype and always present the phenotype associated with the dominant gene.

However, if the F1-generation is further crossed with the F1-generation (heterozygote crossed with heterozygote) the offspring (F2-generation) will present the phenotype associated with the dominant gene ¾ times. Although heterozygote monohybrid crossing can result in two phenotype variants, it can result in three genotype variants - homozygote dominant, heterozygote and homozygote recessive, respectively.[11]

Indihybridinheritancewe look at the inheritance of two pairs of genes simultaneous. Assuming here that the two pairs of genes are located at non-homologous chromosomes, such that they are not coupled genes (seegenetic linkage) but instead inherited independently. Consider now the cross between parents (P-generation) of genotypes homozygote dominant and recessive, respectively. The offspring (F1-generation) will always heterozygous and present the phenotype associated with the dominant allele variant.

However, when crossing the F1-generation there are four possible phenotypic possibilities and the phenotypicalratiofor the F2-generation will always be 9:3:3:1.[12]

Incomplete dominance (non-Mendelian)

[edit]

Incomplete dominance (also calledpartial dominance,semi-dominance,intermediate inheritance,or occasionally incorrectlyco-dominancein reptile genetics[13]) occurs when the phenotype of the heterozygous genotype is distinct from and often intermediate to the phenotypes of the homozygous genotypes. The phenotypic result often appears as a blended form of characteristics in the heterozygous state. For example, thesnapdragonflower color is homozygous for either red or white. When the red homozygous flower is paired with the white homozygous flower, the result yields a pink snapdragon flower. The pink snapdragon is the result of incomplete dominance. A similar type of incomplete dominance is found in thefour o'clock plantwherein pink color is produced when true-bred parents of white and red flowers are crossed. Inquantitative genetics,where phenotypes are measured and treated numerically, if a heterozygote's phenotype is exactly between (numerically) that of the two homozygotes, the phenotype is said to exhibitno dominanceat all, i.e. dominance exists only when the heterozygote's phenotype measure lies closer to one homozygote than the other.

When plants of the F1generation are self-pollinated, the phenotypic and genotypic ratio of the F2generation will be 1:2:1 (Red:Pink:White).[14]

Co-dominance (non-Mendelian)

[edit]

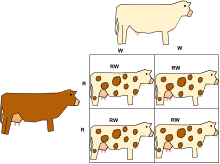

Co-dominance occurs when the contributions of both alleles are visible in the phenotype and neither allele masks another.

For example, in theABO blood group system,chemical modifications to aglycoprotein(the H antigen) on the surfaces of blood cells are controlled by three alleles, two of which are co-dominant to each other (IA,IB) and dominant over the recessiveiat theABO locus.TheIAandIBalleles produce different modifications. The enzyme coded for byIAadds an N-acetylgalactosamine to a membrane-bound H antigen. TheIBenzyme adds a galactose. Theiallele produces no modification. Thus theIAandIBalleles are each dominant toi(IAIAandIAiindividuals both have type A blood, andIBIBandIBiindividuals both have type B blood), butIAIBindividuals have both modifications on their blood cells and thus have type AB blood, so theIAandIBalleles are said to be co-dominant.[14]

Another example occurs at the locus for thebeta-globincomponent ofhemoglobin,where the three molecular phenotypes ofHbA/HbA,HbA/HbS,andHbS/HbSare all distinguishable byprotein electrophoresis.(The medical condition produced by the heterozygous genotype is calledsickle-cell traitand is a milder condition distinguishable fromsickle-cell anemia,thus the alleles showincomplete dominanceconcerning anemia, see above). For most gene loci at the molecular level, both alleles are expressed co-dominantly, because both aretranscribedintoRNA.[14]

Co-dominance, where allelic products co-exist in the phenotype, is different from incomplete dominance, where the quantitative interaction of allele products produces an intermediate phenotype. For example, in co-dominance, a red homozygous flower and a white homozygous flower will produce offspring that have red and white spots. When plants of the F1 generation are self-pollinated, the phenotypic and genotypic ratio of the F2 generation will be 1:2:1 (Red:Spotted:White). These ratios are the same as those for incomplete dominance. Again, this classical terminology is inappropriate – in reality, such cases should not be said to exhibit dominance at all.[14]

Relationship to other genetic concepts

[edit]Dominance can be influenced by various genetic interactions and it is essential to evaluate them when determining phenotypic outcomes.Multiple alleles,epistasisandpleiotropicgenes are some factors that might influence the phenotypic outcome.[15]

Multiple alleles

[edit]Although any individual of a diploid organism has at most two different alleles at a given locus, most genes exist in a large number of allelic versions in the population as a whole. This is calledpolymorphism,and is caused by mutations. Polymorphism can have an effect on the dominance relationship and phenotype, which is observed in theABO blood group system.The gene responsible for human blood type have three alleles; A, B, and O, and their interactions result in different blood types based on the level of dominance the alleles expresses towards each other.[15][16]

Pleiotropic genes

[edit]Pleiotropicgenesare genes where one single gene affects two or more characters (phenotype). This means that a gene can have a dominant effect on one trait, but a more recessive effect on another trait.[17]

Epistasis

[edit]Epistasis is interactions between multiple alleles at different loci. Easily said, several genes for one phenotype. The dominance relationship between alleles involved in epistatic interactions can influence the observed phenotypic ratios in offspring.[18]

See also

[edit]- Ambidirectional dominance

- List of Mendelian traits in humans

- Mitochondrial DNA

- Punnett square

- Penetrance

- Summation theorems (biochemistry)

- Chimerism

References

[edit]- ^"dominance".Oxford Dictionaries Online.Oxford University Press. Archived fromthe originalon July 18, 2012.Retrieved14 May2014.

- ^"express".Oxford Dictionaries Online.Oxford University Press. Archived fromthe originalon July 18, 2012.Retrieved14 May2014.

- ^Eggers, Stefanie; Sinclair, Andrew (2012). "Mammalian sex determination—insights from humans and mice".Chromosome Res.20(1). Dordrecht: Springer-Verlag: 215–238.doi:10.1007/s10577-012-9274-3.hdl:11343/270255.ISSN0967-3849.PMID22290220.

- ^Bateson, William; Mendel, Gregor (2009).Mendel's Principles of Heredity: A Defence, with a Translation of Mendel's Original Papers on Hybridisation.Cambridge University Press.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511694462.ISBN978-1108006132.

- ^abBilliard, Sylvain; Castric, Vincent; Llaurens, Violaine (2021)."The integrative biology of genetic dominance".Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc.96(6). Oxford, UK: Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd: 2925–2942.doi:10.1111/brv.12786.PMC9292577.PMID34382317.

- ^Griffiths AJF; Gelbart WM; Miller JH; et al. (1999)."Gene Interaction Leads to Modified Dihybrid Ratios".Modern Genetic Analysis.New York: W. H. Freeman & Company.ISBN978-0-7167-3118-4.

- ^Mayo, O. and Bürger, R. 1997.The evolution of dominance: A theory whose time has passed?Archived2016-03-04 at theWayback Machine"Biological Reviews", Volume 72, Issue 1, pp. 97–110

- ^Bourguet, D. 1999.The evolution of dominanceArchived2016-08-29 at theWayback MachineHeredity,Volume 83, Number 1, pp. 1–4

- ^Bagheri, H.C. 2006.Unresolved boundaries of evolutionary theory and the question of how inheritance systems evolve: 75 years of debate on the evolution of dominanceArchived2019-07-02 at theWayback Machine"Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution", Volume 306B, Issue 4, pp. 329–359

- ^Rodríguez-Beltrán, Jerónimo; Sørum, Vidar; Toll-Riera, Macarena; de la Vega, Carmen; Peña-Miller, Rafael; San Millán, Álvaro (2020)."Genetic dominance governs the evolution and spread of mobile genetic elements in bacteria".Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.117(27). United States: United States: National Academy of Sciences: 15755–15762.Bibcode:2020PNAS..11715755R.doi:10.1073/pnas.2001240117.ISSN0027-8424.PMC7355013.PMID32571917.

- ^Trudy, F. C. Mackay; Robert, R. H. Anholt (2022)."Gregor Mendel's legacy in quantitative genetics".PLOS Biology.20(7). Public Library of Science (PLoS): e3001692.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001692.ISSN1544-9173.PMC9295954.PMID35852997.

- ^Alberts, Bruce; Heald, Rebecca; Hopkin, Karen; Johnson, Alexander; Morgan, David; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2023).Essential cell biology(Sixth edition.; International student ed.). W.W. Norton & Company.ISBN9781324033394.

- ^Bulinski, Steven (2016-01-05)."A Crash Course in Reptile Genetics".Reptiles.Living World Media. Archived fromthe originalon 2020-02-04.Retrieved2023-02-03.

The term co-dominant is often used interchangeably with incomplete dominant, but the two terms have different meanings.

- ^abcdBrown, T. A. (2018).Genomes 4(4th ed.). Milton: Milton: Garland Science.doi:10.1201/9781315226828.ISBN9780815345084.S2CID239528980.

- ^abIngelman-Sundberg, M. (2005). "Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functional diversity".Pharmacogenomics J.5(1). United States: United States: Nature Publishing Group: 6–13.doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500285.ISSN1470-269X.PMID15492763.S2CID10695794.

- ^Yamamoto, F; Clausen, H; White, T; Marken, J; Hakomori, S (1990). "Molecular genetic basis of the histo-blood group ABO system".Nature.345(6272): 229–233.Bibcode:1990Natur.345..229Y.doi:10.1038/345229a0.PMID2333095.S2CID4237562.

- ^Du, Qingzhang; Tian, Jiaxing; Yang, Xiaohui; Pan, Wei; Xu, Baohua; Li, Bailian; Ingvarsson, Pär K.; Zhang, Deqiang (2015)."Identification of additive, dominant, and epistatic variation conferred by key genes in cellulose biosynthesis pathway in Populus tomentosa".DNA Res.22(1). England: England: Oxford University Press: 53–67.doi:10.1093/dnares/dsu040.ISSN1340-2838.PMC4379978.PMID25428896.

- ^Phillips, Patrick C (2008)."Epistasis - the essential role of gene interactions in the structure and evolution of genetic systems".Nat Rev Genet.9(11). London: London: Nature Publishing Group: 855–867.doi:10.1038/nrg2452.ISSN1471-0056.PMC2689140.PMID18852697.

- "On-line notes for Biology 2250 – Principles of Genetics".Memorial University of Newfoundland.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man(OMIM):Hemoglobin—Beta Locus; HBB - 141900— Sickle-Cell Anemia

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man(OMIM):ABO Glycosyltransferase - 110300— ABO blood groups