Religion in politics

Religion in politicscovers various topics related to the effects ofreligiononpolitics.Religion has been claimed to be "the source of some of the most remarkable political mobilizations of our times".[1]

Religious political doctrines

[edit]Various political doctrines have been directly influenced or inspired by religions. Various strands ofpolitical Islamexist, with most of them falling under the umbrella term ofIslamism.Graham Fullerhas argued for a broader notion of Islamism as a form ofidentity politics,involving "support for [Muslim] identity, authenticity, broader regionalism, revivalism, [and] revitalization of the community."[2]This frequently may take asocially conservativeorreactionaryform, as inwahhabismandsalafism.Ideologies which espouseIslamic modernismincludeIslamic socialismandpost-Islamism.

Christian political movementsrange fromChristian socialism,Christian communism,andChristian anarchismon theleft,toChristian democracyonthe centre,[3]to theChristian right.

Beyonduniversalistideologies, religions have also beeninvolved in nationalist politics.Hindu nationalismexists in theHindutvamovement.Religious Zionismseeks to create areligious Jewish state.TheKhalistan movementaims to create a homeland forSikhs.

An extreme form of religious political action isreligious terrorism.Islamic terrorismhas been evident in the actions of theIslamic State,Boko Haram,theTalibanandAl-Qaeda,all of these organizations practicejihadism.Christian terrorismhas been connected toanti-abortion violenceandwhite supremacy,[4]for example in theChristian Identitymovement.Saffron terrordescribes terrorism connected toHinduism.There has also been cases ofJewish religious terrorism,such as theCave of the Patriarchs massacre,as well as ofSikhterrorism, such as the bombing ofAir India Flight 182.

Religious political issues

[edit]Religious political issues may involve, but are not limited to, those concerningfreedom of religion,applications ofreligious law,and the right toreligious education.

Religion and the state

[edit]Stateshave adopted various attitudes towards religions, ranging fromtheocracytostate atheism.

A theocracy is "government by divine guidance or by officials who are regarded as divinely guided".[5] Modern day recognised theocracies include theIslamic Republic of Iran[6]and theHoly See,[7]while theTalibanandIslamic Stateare insurgencies attempting to create suchpolities.Historical examples include the IslamicCaliphatesand thePapal States.

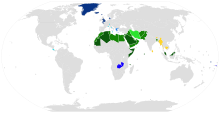

A more modest form of religious state activity is having an officialstate religion.Unlike a theocracy, this maintains the superiority of the state over the religious authorities. Over 20% (a total of 43) of the countries in the world have a state religion, most of them (27) being Muslim countries.[8]There are also 13 officiallyBuddhistcountries such asBhutan,[9]while state churches are present in 27 countries.

In contrast to religious states,secular statesrecognise no religion. This is often called the principle of theseparation of church and state.A more strictly prescribed version,Laïcité,is practiced inFrance,which prohibits all religious expressions in many public contexts.[10]

Some states areexplicitly atheistic,usually those which were produced byrevolution,such as varioussocialist statesor theFrench First Republic.

There have also been cases of statescreating their own religions,such asimperial cultsor theCult of Reason.

Religion and political behaviour

[edit]Frameworks on religion and political identity

[edit]Understanding religion’s impact onpolitical behaviouris essential because of its complex relationship to the individual: for a political subject, faith is at once anideologyand anidentity.[11]As a result, political scientists are divided on whether to consider it alongside otherethnic cleavagessuch asrace,language,caste,andtribe,or whether to recognise it as a separate, special kind of political influence.[12]

Daniel N. Posner holds the former perspective: that religion should be conflated with identity. He underlines that identity is important in politics not because of some “passions [or] traditions it embodies”, but because it reflects “the expected behaviour of other political factors”.[13]In such aframework,religion is treated as afungiblelabel that can be ‘activated’ and constitute a criterion for membership in anethnic group.[14]

The latter perspective has been argued by relatively recent scholars, advocating for “(More) Serious”[11]attention to religion in Comparative Politics. Grzymala-Busse outlines three often overlooked characteristics of religion which differentiate it from other markers ofidentity:

- Its power to transcend national boundaries. Religion ss arguably the largest unit to which individuals claim loyalty (Islam claims roughly 1.5 billion adherents, Christianity roughly 2 billion – respectively 22% and 33% of the world’s population).[11]

- Its demanding commitment by followers to a specific lifestyle, affectingdress codes,diets,political views– religion proposes an alternative lifestyle defined by “supernatural”forces.[15]

- Its strength of resistance tosecularonslaughtbecause of abnormally “high stakes” like eternalsalvationordamnation,making religion much less “pliable” than other ethnic identities.[11]

Considering these characteristics, it becomes possible to consider religion as a unique identityvariablewith immense power. Several analyses even regard religion as avariableso potent that it is able to reinforce other identities, and as a result allows religious components insecularspheres ofsociety(see: Iversen and Rosenbluth, 2006; Trejo, 2009; Grossman, 2015).[16][17][18]

Debates about religion in politics

[edit]There have been arguments for and against a role for religion in politics.Yasmin Alibhai-Brownhas argued that "faith and state should be kept separate" as "the most sinister and oppressive states in the world are those that use God to control the minds and actions of their populations", such asIranandSaudi Arabia.[19]To this,Dawn Fosterhas responded that when religion is fully unmoored from politics it becomes all the more insular and more open to abuse.[19]

See also

[edit]- Christianity and politics

- Judaism and politics

- Political aspects of Islam

- List of political ideologies § Religious ideologies

- Religion and politics in the United States

References

[edit]- ^Jelen, Ted G. (2002).Religion and Politics in Comparative Perspective.Cambridge University Press. p. 1.

- ^Fuller, Graham E.,The Future of Political Islam,Palgrave MacMillan, (2003), p. 21

- ^Boswell, Jonathan (2013).Community and the Economy: The Theory of Public Co-operation.Routledge. p. 160.ISBN9781136159015.

- ^"Hate In God's Name".Southern Poverty Law Center.Retrieved2019-12-01.

- ^"Theocracy | political system".Encyclopedia Britannica.Retrieved2019-12-01.

- ^"Inside Iran - The Structure Of Power In Iran | Terror And Tehran | FRONTLINE | PBS".www.pbs.org.Retrieved2019-12-01.

- ^"Vatican City Created".National Geographic Society.2013-12-16.Retrieved2019-12-01.

- ^correspondent, Harriet Sherwood Religion (2017-10-03)."More than 20% of countries have official state religions – survey".The Guardian.ISSN0261-3077.Retrieved2019-12-01.

- ^"Religion".www.bhutan.com.Retrieved2019-12-01.

- ^Winkler, Elizabeth (2016-01-07)."Is it Time for France to Abandon Laïcité?".The New Republic.ISSN0028-6583.Retrieved2019-12-01.

- ^abcdAnna Grzymala-Busse,“Why Comparative Politics Should Take Religion (More) Seriously,”Annual Review of Political Science 15, no. 1 (June 15, 2012): 421–42,https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-033110-130442

- ^Kenneth D. Wald and Clyde Wilcox,“Getting Religion: Has Political Science Rediscovered the Faith Factor?,”American Political Science Review 100, no. 04 (November 2006): 523,https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055406062381.

- ^Posner, Daniel N.Institutions and Ethnic Politics in Africa.Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- ^Chandra K, ed. 2012.Constructivist Theories of Ethnic Politics.Unpublished manuscript, Department of Political Science, New York University.

- ^Stark R, Finke R. 2000.Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion.Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^Torben Iversen and Frances Rosenbluth,“The Political Economy of Gender: Explaining Cross-National Variation in the Gender Division of Labor and the Gender Voting Gap,”American Journal of Political Science 50, no. 1 (2006): 1–19,https://www.jstor.org/stable/3694253.

- ^Trejo 2009. “Religious competition and ethnic mobilization in Latin America: why the Catholic Church promotes indigenous movements in Mexico.

- ^Guy Grossman,“Renewalist Christianity and the Political Saliency of LGBTs: Theory and Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa,”The Journal of Politics 77, no. 2 (April 2015): 337–51,https://doi.org/10.1086/679596.

- ^ab"Should religion play a role in politics?".New Internationalist.2019-01-29.Retrieved2019-12-01.