Second Spanish Republic

Spanish Republic República Española(Spanish) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1931–1939 | |||||||||||

| Motto:Plus Ultra(Latin) Further Beyond | |||||||||||

| Anthem:Himno de Riego Anthem of Riego | |||||||||||

European borders of the Second Spanish Republic in addition to its African colonies | |||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | Madrid[a] | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish[b] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Secular State Roman Catholic(majority) | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Spanish,Spaniard | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitarysemi-presidentialrepublic[1] | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1931–1936 | Niceto Alcalá-Zamora | ||||||||||

• 1936(interim) | Diego Martínez Barrio | ||||||||||

• 1936–1939 | Manuel Azaña | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1931(first) | Niceto Alcalá-Zamora | ||||||||||

• 1937–1939(last) | Juan Negrín | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Republicanas | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||||

| 14 April 1931 | |||||||||||

| 9 December 1931 | |||||||||||

| 5–19 October 1934 | |||||||||||

| 17 July 1936 | |||||||||||

| 1 April 1939 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish peseta | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

TheSpanish Republic(Spanish:República Española), commonly known as theSecond Spanish Republic(Spanish:Segunda República Española), was the form of democratic government inSpainfrom 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931 after the deposition ofKing Alfonso XIII.It was dissolved on 1 April 1939 after surrendering in theSpanish Civil Warto theNationalistsled by GeneralFrancisco Franco.

After the proclamation of the Republic,a provisional governmentwas established until December 1931, at which time the1931 Constitutionwas approved. During this time and the subsequent two years of constitutional government, known as theReformist Biennium,Manuel Azaña's executive initiated numerous reforms to what in their view would modernize the country. In 1932religious orderswere forbidden control of schools, while the government began a large-scale school-building project. A moderate agrarian reform was carried out. Home rule was granted toCatalonia,with a local parliament and a president of its own.[2]

Soon, Azaña lost parliamentary support and PresidentAlcalá-Zamoraforced his resignation in September 1933. The subsequent1933 electionwas won by theSpanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right(CEDA). However the President declined to invite its leader,Gil Robles,to form a government, fearing CEDA's monarchist sympathies. Instead, he invited theRadical Republican Party'sAlejandro Lerrouxto do so. CEDA was denied cabinet positions for nearly a year.[3]In October 1934, CEDA was finally successful in forcing the acceptance of three ministries. The Socialists triggered an insurrection that they had been preparing for nine months.[4]A general strike was called by theUnión General de Trabajadores(UGT) and theSpanish Socialist Workers' Party(PSOE) in the name of theAlianza Obrera.[5]The rebellion developed into a bloodyrevolutionary uprising,aiming to overthrow the republican government. Armed revolutionaries managed to take the whole province ofAsturias,killing policemen, clerics, and businessmen and destroying religious buildings and part of theUniversity of Oviedo.[6]In the occupied areas, the rebels officially declared a proletarian revolution and abolished regular money.[7]The rebellion was crushed by theSpanish Navyand theSpanish Republican Army,the latter using mainlyMoorish colonial troopsfromSpanish Morocco.[8]

In 1935, after a series of crises and corruption scandals, PresidentAlcalá-Zamora,who had always been hostile to the government, called for new elections, instead of inviting CEDA, the party with most seats in the parliament, to form a new government. ThePopular Frontwon the1936 general electionwith a narrow victory. The Right accelerated its preparations for a coup, which had been months in the planning.[9][10]

Amidst the wave of political violence that broke out after the triumph of the Popular Front in the February 1936 elections, a group ofGuardia de Asaltoand other leftist militiamenmortally shotthe opposition leaderJosé Calvo Soteloon 12 July 1936. This assassination convinced many military officers to back the planned coup. Three days later (17 July), the revolt began with an army uprising inSpanish Morocco,followed by military takeovers in many cities in Spain. Military rebels intended to seize power immediately, but they were met with serious resistance as most of the main cities remained loyal to the Republic. An estimated total of half a million people would die in the war that followed.

During the Spanish Civil War, there were three Republican governments. The first was led by left-wing republicanJosé Giral(from July to September 1936); arevolutioninspired mostly bylibertarian socialist,anarchistandcommunistprinciples broke out in its territory. The second government was led by the PSOE'sFrancisco Largo Caballero.The UGT, along with theNational Confederation of Workers(CNT), were the main forces behind thesocial revolution.The third government was led by socialistJuan Negrín,who led the Republic until the military coup ofSegismundo Casado,which ended republican resistance and ultimately led to the victory of the Nationalists.

The Republican government survivedin exileand retained an embassy inMexico Cityuntil 1976. After the restoration of democracy in Spain, the government-in-exile formally dissolved the following year.[11]

History

[edit]1931–1933, the Reformist Biennium

[edit]On 28 January 1930, the military dictatorship of GeneralMiguel Primo de Rivera(who had been in powersince September 1923) was overthrown.[12]This led various republican factions from a wide variety of backgrounds (including conservatives, socialists and Catalan nationalists) to join forces.[13]ThePact of San Sebastiánwas the key to the transition from monarchy to republic. Republicans of all tendencies were committed to the Pact of San Sebastian in overthrowing the monarchy and establishing a republic. The restoration of the royal Bourbons was rejected by large sectors of the populace who vehemently opposed the King. The pact, signed by representatives of the main Republican forces, allowed a joint anti-monarchy political campaign.[14]The12 April 1931 municipal electionsled to a landslide victory for republicans.[15]Two days later, the Second Republic was proclaimed, and KingAlfonso XIIIwent into exile.[16]The king's departure led to aprovisional governmentof the young republic underNiceto Alcalá-Zamora.Catholic churches and establishments in cities likeMadridandSevillawereset ablazeon 11 May.[17]

1931 Constitution

[edit]

In June 1931 aConstituent Corteswas elected to draft a new constitution, which came into force in December.[18]

The new constitution establishedfreedom of speechandfreedom of association,extendedsuffrageto women in 1933, allowed divorce, and stripped the Spanish nobility of any special legal status. It also effectively disestablished[clarification needed]theRoman Catholic Church,but the disestablishment was somewhat reversed by the Cortes that same year. Its controversial articles 26 and 27 imposed stringent controls on Church property and barred religious orders from the ranks of educators.[19]Scholars have described the constitution as hostile to religion, with one scholar characterising it as one of the most hostile of the 20th century.[20]José Ortega y Gassetstated, "the article in which the Constitution legislates the actions of the Church seems highly improper to me."[21]Pope Pius XIcondemned the Spanish government's deprivation of thecivil libertiesof Catholics in theencyclicalDilectissima Nobis.[22]

The legislative branch was changed to a single chamber called theCongress of Deputies.The constitution established legal procedures for thenationalisationof public services and land, banks, and railways. The constitution provided generally accorded civil liberties and representation.[23]

The Republican Constitution also changed the country's national symbols. TheHimno de Riegowas established as the national anthem, and theTricolor,with three horizontal red-yellow-purple fields, became the new flag of Spain. Under the new Constitution, all of Spain's regions had the right toautonomy.Catalonia(1932), theBasque Country(1936) andGalicia(although the Galician Statute of Autonomy could not come into effect due to the war) exercised this right, withAragon,AndalusiaandValencia,engaged in negotiations with the government before the outbreak of the Civil War. The Constitution guaranteed a wide range of civil liberties, but it opposed key beliefs of the right wing, which was very rooted in rural areas, and desires of the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church, which was stripped of schools and public subsidies.

The 1931 Constitution was formally effective from 1931 until 1939. In the summer of 1936, after the outbreak of theSpanish Civil War,it became largely irrelevant after the authority of the Republic was superseded in many places by revolutionary socialists and anarchists on one side, and Nationalists on the other.[24]

Azaña government

[edit]With the new constitution approved in December 1931, once the constituent assembly had fulfilled its mandate of approving a new constitution, it should have arranged for regular parliamentary elections and adjourned. However, fearing the increasing popular opposition, the Radicals and Socialist majority postponed the regular elections, therefore prolonging their way in power for two more years. This way the republican government ofManuel Azañainitiated numerous reforms to what in their view would "modernize" the country.[2]

Landowners were expropriated. Autonomy was granted to Catalonia, with a local parliament and a president of said parliament.[2]Catholic churches in major cities were again subject to arson in 1932, and a revolutionary strike action was seen inMálagathe same year.[17]A Catholic church inZaragozawas burnt down in 1933.

In November 1932,Miguel de Unamuno,one of the most respected Spanish intellectuals, rector of the University of Salamanca, and himself a Republican, publicly raised his voice to protest. In a speech delivered on 27 November 1932, at the Madrid Ateneo, he protested: "Even the Inquisition was limited by certain legal guarantees. But now we have something worse: a police force which is grounded only on a general sense of panic and on the invention of non-existent dangers to cover up this over-stepping of the law."[25]

In 1933, all remaining religious congregations were obliged to pay taxes and banned from industry, trade and educational activities. This ban was forced with strict police severity and widespread mob violence.[26]

1933–1935 period and miners' uprising

[edit]

The majority vote in the1933 electionswas won by theSpanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right(CEDA). In face of CEDA's electoral victory, presidentAlcalá-Zamoradeclined to invite its leader, Gil Robles, to form a government. Instead he invited theRadical Republican Party'sAlejandro Lerrouxto do so. Despite receiving the most votes, CEDA was denied cabinet positions for nearly a year.[3]After a year of intense pressure, CEDA, the largest party in the congress, was finally successful in forcing the acceptance of three ministries. However the entrance of CEDA in the government, although being normal in a parliamentary democracy, was not well accepted by the left. The Socialists triggered an insurrection that they had been preparing for nine months.[4]A general strike was called by the UGT and the PSOE in the name of theAlianza Obrera.The issue was that the Left Republicans identified the Republic not with democracy or constitutional law but with a specific set of left-wing policies and politicians. Any deviation, even if democratic, was seen as treasonous.[5]

The inclusion of three CEDA ministers in the government that took office on 1 October 1934 led to a country wide revolt. A "Catalan State"was proclaimed by Catalan nationalist leaderLluis Companys,but it lasted just ten hours. Despite an attempt at a general stoppage inMadrid,other strikes did not endure. This leftAsturianstrikers to fight alone.[27]Miners in Asturias occupied the capital,Oviedo,killing officials and clergymen. Fifty eight religious buildings including churches, convents and part of the university at Oviedo were burned and destroyed.[28][29]The miners proceeded to occupy several other towns, most notably the large industrial centre ofLa Felguera,and set up town assemblies, or "revolutionary committees", to govern the towns that they controlled.[28]Thirty thousand workers were mobilized for battle within ten days.[28]In the occupied areas the rebels officially declared the proletarian revolution and abolished regular money.[7]The revolutionary soviets set up by the miners attempted to impose order on the areas under their control, and the moderate socialist leadership ofRamón González PeñaandBelarmino Tomástook measures to restrain violence. However, a number of captured priests, businessmen and civil guards were summarily executed by the revolutionaries inMieresandSama.[28]This rebellion lasted for two weeks until it was crushed by the army, led by GeneralEduardo López Ochoa.This operation earned López Ochoa the nickname "Butcher of Asturias".[30]Another rebellion by the autonomous government of Catalonia, led by its presidentLluís Companys,was also suppressed and was followed by mass arrests and trials.

With this rebellion against an established political legitimate authority, the Socialists showed identical repudiation of representative institutional system that anarchists had practiced.[31]The Spanish historianSalvador de Madariaga,an Azaña supporter and an exiled vocal opponent of Francisco Franco, is the author of a sharp critical reflection against the participation of the left in the revolt: "The uprising of 1934 is unforgivable. The argument that Mr Gil Robles tried to destroy the Constitution to establish fascism was, at once, hypocritical and false. With the rebellion of 1934, the Spanish left lost even the shadow of moral authority to condemn the rebellion of 1936."[32]

The suspension of the land reforms that had been attempted by the previous government, and the failure of the Asturias miners' uprising, led to a more radical turn by the parties of the left, especially in the PSOE (Socialist Party), where the moderateIndalecio Prietolost ground toFrancisco Largo Caballero,who advocated a socialist revolution. At the same time, the involvement of the Centrist government party in theStraperloandNombelascandals deeply weakened it, further polarising political differences between right and left. These differences became evident in the 1936 elections.

1936 elections

[edit]

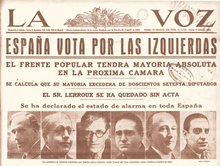

On 7 January 1936,new electionswere called. Despite significant rivalries and disagreements, the socialists, Communists, and the Catalan-and-Madrid-based left-wing Republicans decided to work together under the namePopular Front.The Popular Front won the election on 16 February with 263 MPs against 156 right-wing MPs, grouped within a coalition of theNational Frontwith CEDA,Carlists,and Monarchists. The moderate centre parties virtually disappeared; between the elections, Lerroux's group fell from the 104 representatives it had in 1934 to just 9.

American historianStanley G. Paynethinks that there was major electoral fraud in the process, with widespread violation of the laws and the constitution.[33]In line with Payne's point of view, in 2017, two Spanish Scholars, Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García, published the result of a research where they concluded that the 1936 elections were rigged.[34][35]This view has been criticised by Eduardo Calleja and Francisco Pérez, who question the charges of electoral irregularity and argue that the Popular Front would still have won a slight electoral majority even if all of the charges were true.[36]

In the thirty-six hours following the election, sixteen people were killed (mostly by police officers attempting to maintain order or intervene in violent clashes) and thirty-nine were seriously injured, while fifty churches and seventy right wing political centres were attacked or set ablaze.[37]The right had firmly believed, at all levels, that they would win. Almost immediately after the results were known, a group of monarchists asked Robles to lead a coup, but he refused. He did, however, ask prime ministerManuel Portela Valladaresto declare a state of war before the revolutionary masses rushed into the streets. Franco also approached Valladares to propose the declaration of martial law and calling out of the army. This was not a coup attempt, but more of a "police action" akin toAsturias,as Franco believed the post-election environment could become violent and was trying to quell the perceived leftist threat.[38][10][39]Valladares resigned, even before a new government could be formed. However, the Popular Front, which had proved an effective election tool, did not translate into a Popular Front government.[40]Largo Caballeroand other elements of the political left were not prepared to work with the republicans, although they did agree to support many of the proposed reforms.Manuel Azañawas called upon to form a government before the electoral process had come to an end, and he would shortly replace Zamora as president, taking advantage of a constitutional loophole: the Constitution allowed the Cortes to remove the President from office after two early dissolutions, and while the first (1933) dissolution had been partially justified because of the fulfillment of the Constitutional mission of the first legislature, the second one had been a simple bid to trigger early elections.[40]

The right reacted as if radical communists had taken control, despite the new cabinet's moderate composition; they were shocked by the revolutionary masses taking to the streets and the release of prisoners. Convinced that the left was no longer willing to follow the rule of law and that its vision of Spain was under threat, the right abandoned the parliamentary option and began to conspire as to how to best overthrow the republic, rather than taking control of it.[41][42]

This helped the development of the fascist-inspiredFalangeEspañola, a National party led byJosé Antonio Primo de Rivera,the son of the former dictator,Miguel Primo de Rivera,although it only received 0.7 percent of the votes in the election. By July 1936, the Falange had a mere 40,000 members among millions of Spaniards.

The country quickly moved towards anarchy. Even the socialistIndalecio Prieto,at a party rally in Cuenca in May 1936, complained: "we have never seen so tragic a panorama or so great a collapse as in Spain at this moment. Abroad Spain is classified as insolvent. This is not the road to socialism or communism but to desperate anarchism without even the advantage of liberty."[43]

In June 1936,Miguel de Unamuno,disenchanted with the unfolding of the events, told a reporter who published his statement inEl Adelantothat PresidentManuel Azañashould commit suicide as a patriotic act.[44]

Assassinations of political leaders and beginning of the war

[edit]

On 12 July 1936, LieutenantJosé Castillo,an important member of the anti-fascist military organisationUnión Militar Republicana Antifascista(UMRA), was shot byFalangistgunmen.

In response, a group ofGuardia de Asaltoand other leftist militiamen led byCivil GuardFernando Condés, after getting the approval of the minister of interior to illegally arrest a list of members of parliament, went to right-wing opposition leaderJosé Calvo Sotelo's house in the early hours of 13 July on a revenge mission. Sotelo was arrested and latershot deadin a police truck. His body was dropped at the entrance of one of the city's cemeteries. According to all later investigations, the perpetrator of the murder was a socialist gunman, Luis Cuenca, who was known as the bodyguard ofPSOEleaderIndalecio Prieto.Calvo Sotelo was one of the most prominent Spanish monarchists who, describing the government's actions asBolshevistand anarchist, had been exhorting the army to intervene, declaring that Spanish soldiers would save the country from communism if "there are no politicians capable of doing so".[45]

Prominent rightists blamed the government forCalvo Sotelo's assassination.They claimed that the authorities did not properly investigate it and promoted those involved in the murder whilst censoring those who cried out about it and shutting down the headquarters of right-wing parties and arresting right-wing party members, often on "flimsy charges".[46]The event is often considered the catalyst for the further political polarisation that ensued. The Falange and other right-wing individuals, includingJuan de la Cierva,had already been conspiring to launch a military coup d'état against the government, to be led by senior army officers.[47]

When the antifascist Castillo and the anti-socialist Calvo Sotelo were buried on the same day in the same Madrid cemetery, fighting between thePolice Assault Guardand fascist militias broke out in the surrounding streets, resulting in four more deaths.

Thekilling of Calvo Sotelowith police involvement aroused suspicions and strong reactions among the government's opponents on the right.[48]Although the nationalist generals were already planning an uprising, the event was a catalyst and a public justification for a coup.[49]Stanley Payneclaims that before these events, the idea of rebellion by army officers against the government had weakened; Mola had estimated that only 12% of officers reliably supported the coup and at one point considered fleeing the country for fear he was already compromised, and had to be convinced to remain by his co-conspirators.[50]However, thekidnapping and murder of Sotelotransformed the "limping conspiracy" into a revolt that could trigger a civil war.[51][52]The involvement of forces of public order and a lack of action against the attackers hurt public opinion of the government. No effective action was taken; Payne points to a possible veto by socialists within the government who shielded the killers who had been drawn from their ranks. The murder of a parliamentary leader by state police was unprecedented, and the belief that the state had ceased to be neutral and effective in its duties encouraged important sectors of the right to join the rebellion.[53]Within hours of learning of the murder and the reaction,Franco,who until then had not been involved in the conspiracies, changed his mind on rebellion and dispatched a message toMolato display his firm commitment.[54]

Three days later (17 July), thecoup d'étatbegan more or less as it had been planned, with an army uprising inSpanish Morocco,which then spread to several regions of the country.

The revolt was remarkably devoid of any particular ideology.[contradictory][55]The major goal was to put an end to anarchical disorder.[dubious–discuss][55]Mola's plan for the new regime was envisioned as a "republican dictatorship", modelled afterSalazar'sPortugal and as a semi-pluralist authoritarian regime rather than a totalitarian fascist dictatorship. The initial government would be an all-military "Directory", which would create a "strong and disciplined state." General Sanjurjo would be the head of this new regime, due to being widely liked and respected within the military, though his position would be a largely symbolic due to his lack of political talent. The 1931 Constitution would be suspended, replaced by a new "constituent parliament" which would be chosen by a new politically purged electorate, who would vote on the issue of republic versus monarchy. Certain liberal elements would remain, such as separation of church and state as well as freedom of religion. Agrarian issues would be solved by regional commissioners on the basis of smallholdings, but collective cultivation would be permitted in some circumstances. Legislation prior to February 1936 would be respected. Violence would be required to destroy opposition to the coup, though it seems Mola did not envision the mass atrocities and repression that would ultimately manifest during the civil war.[56][57]Of particular importance to Mola was ensuring the revolt was at its core an Army affair, one that would not be subject to special interests and that the coup would make the armed forces the basis for the new state.[58]However, the separation of church and state was forgotten once the conflict assumed the dimension of a war of religion, and military authorities increasingly deferred to the Church and to the expression of Catholic sentiment.[59]However, Mola's program was vague and only a rough sketch, and there were disagreements among coupists about their vision for Spain.[60][61]

Franco's move was intended to seize power immediately, but his army uprising met with serious resistance, and great swathes of Spain, including most of the main cities, remained loyal to the Republic of Spain. The leaders of the coup (Franco was not commander-in-chief yet) did not lose heart with the stalemate and apparent failure of the coup. Instead, they initiated a slow and determined war of attrition against the Republican government in Madrid.[62] As a result, an estimated total of half a million people would die in the war that followed; the number of casualties is actually disputed, as some have suggested that as many as a million people died. Over the years, historians kept lowering the death figures, and modern research concluded that 500,000 deaths were the correct figure.[63]

Civil War

[edit]

On 17 July 1936, General Franco led theSpanish Army of Africafrom Morocco to attack the mainland, while another force from the north under GeneralEmilio Molamoved south from Navarre. Military units were also mobilised elsewhere to take over government institutions. Before long the professional Army of Africa had much of the south and west under the control of the rebels and by October 1936, Time Magazine declared that "façade of the Spanish Republic was crumbling".[64]Bloody purges followed in each piece of captured "Nationalist" territory in order to consolidate Franco's future regime.[62] Although both sides received foreign military aid, the help thatFascist Italy,Nazi Germany(as part of theItalian military intervention in Spainand theGerman involvement in the Spanish Civil War), and neighbouring Portugal gave the rebels was much greater and more effective than the assistance that the Republicans received from the USSR, Mexico, and volunteers of theInternational Brigades.While theAxis powerswholeheartedly assisted General Franco's military campaign, the governments of France, Britain, and other European powers pursued a policy of non-interventionism, as exemplified by the actions of theNon-Intervention Committee.[65]Imposed in the name ofneutrality,theinternational isolationof the Spanish Republic ended up favouring the interests of the futureAxis Powers.[66]

TheSiege of the Alcázarat Toledo early in the war resulted in the rebels winning after a long siege. The Republicans managed to hold out in Madrid, despite a Nationalist assault in November 1936, and frustrated subsequent offensives against the capital atJaramaand Guadalajara in 1937. Soon, though, the rebels began to erode their territory, starving Madrid and making inroads into the east. The north, including the Basque country, fell in late 1937, and the Aragon front collapsed shortly afterward. Thebombing of Guernicawas probably the most infamous event of the war and inspiredPicasso's painting.It was used as a testing ground for the German Luftwaffe'sCondor Legion.TheBattle of the Ebroin July–November 1938 was the final desperate attempt by the Republicans to turn the tide. When this failed and Barcelona fell to the rebels in early 1939, it was clear the war was over. The remaining Republican fronts collapsed, and Madrid fell in March 1939.

Economy

[edit]The Second Spanish Republic's economy was mostly agrarian, and many historians[attribution needed]call Spain during this time a "backward nation". Major industries of the Second Spanish Republic were located in the Basque region (due to it having Europe's best high-grade non-phosphoric ore) and Catalonia. This greatly contributed to Spain's economic hardships, as their center of industry was located on the opposite side of the country from their resource reserves, resulting in immense transportation costs due to the mountainous Spanish terrain. Compounding economic woes was Spain's low export rate and heavily domestic manufacturing industry. High levels of poverty left many Spaniards open to extremist political parties in search of a solution.[67]

See also

[edit]- Spanish Republican Armed Forces

- Spanish Republican government in exile

- Flag of the Second Spanish Republic

- Coat of Arms of the Second Spanish Republic

- Order of the Spanish Republic

- LAPE(Líneas Aéreas Postales Españolas), the Spanish Republican Airline

- Catholicism in the Second Spanish Republic

- Sanjurjada

- Electoral Carlism (Second Republic)

- Reign of Alfonso XIII of Spain

Notes

[edit]- ^Payne, Stanley G.(1993).Spain's First Democracy: The Second Republic, 1931–1936.University of Wisconsin Press.pp. 62–63.ISBN9780299136741.Retrieved2 October2013– viaGoogle Books.

- ^abcHayes 1951,p. 91.

- ^abPayne & Palacios 2018,pp. 84–85.

- ^abPayne & Palacios 2018,p. 88.

- ^abPayne, Stanley G.(2008).The collapse of the Spanish republic, 1933–1936: Origins of the civil war.Yale University Press.pp. 84–85.

- ^Orella Martínez, José Luis; Mizerska-Wrotkowska, Malgorzata (2015).Poland and Spain in the interwar and postwar period.Madrid: Schedas, S.l.ISBN978-8494418068.

- ^abPayne 1993,p. 219.

- ^The Splintering of Spain, p. 54 CUP, 2005

- ^Presto 1983.

- ^abBeevor, Antony.The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939.Hachette UK, 2012.

- ^Rubio, Javier (1977)."Javier Rubio,Los reconocimientos diplomáticos del Gobierno de la República española en el exilio".Revista de Política Internacional(149).Archivedfrom the original on 13 October 2017.Retrieved23 September2016.

- ^Casanova 2010,p. 10

- ^Casanova 2010,p. 1

- ^Mariano Ospina Peña, La II República Española, caballerosandantes.net/videoteca.php?action=verdet&vid=89

- ^Casanova 2010,p. 18

- ^Casanova 2010,p. vii

- ^ab"abc.es:" La quema de iglesias durante la Segunda República "10 May 2012".Archivedfrom the original on 26 October 2018.Retrieved13 June2014.

- ^Casanova 2010,p. 28

- ^Smith, Angel,Historical Dictionary of SpainArchived24 June 2016 at theWayback Machine,p. 195, Rowman & Littlefield 2008

- ^Stepan, Alfred,Arguing Comparative PoliticsArchived15 September 2015 at theWayback Machine,p. 221, Oxford University Press

- ^Paz, Jose Antonio SoutoPerspectives on religious freedom in SpainArchived16 November 2010 at theWayback MachineBrigham Young University Law Review 1 January 2001

- ^Dilectissima Nobis, 2 (On Oppression Of The Church Of Spain)

- ^Payne, Stanley G. (1973)."A History of Spain and Portugal (Print Edition)".University of Wisconsin Press.2, Ch. 25. Library of Iberian resources online: 632.Archivedfrom the original on 18 February 2019.Retrieved30 May2007.

- ^Payne, Stanley G. (1973)."A History of Spain and Portugal (Print Edition)".University of Wisconsin Press.2, Ch. 26. Library of Iberian resources online: 646–647.Archivedfrom the original on 8 November 2017.Retrieved15 May2007.

- ^Hayes 1951,p. 93.

- ^Hayes 1951,p. 92.

- ^Spain 1833–2002,p. 133, Mary Vincent, Oxford, 2007

- ^abcdThomas 1977.

- ^Cueva 1998,pp. 355–369.

- ^Preston, Paul.The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain.Norton, 2012. p. 269

- ^Casanova 2010,p. 138.

- ^Madariaga – Spain (1964) p. 416 as cited inOrella Martínez, José Luis; Mizerska-Wrotkowska, Malgorzata (2015).Poland and Spain in the interwar and postwar period.Madrid: Schedas, S.l.ISBN978-8494418068.

- ^Payne, Stanley G. (8 April 2016)."24 horas – Stanley G. Payne:" Las elecciones del 36, durante la Republica, fueron un fraude "".rtve.Retrieved6 January2020.

- ^Villa García & Álvarez Tardío 2017.

- ^Redondo, Javier (12 March 2017)."El 'pucherazo' del 36"(in Spanish). El Mundo.

- ^Calleja, Eduardo González, and Francisco Sánchez Pérez. "Revisando el revisionismo. A propósito del libro 1936. Fraude y violencia en las elecciones del Frente Popular."Historia Contemporánea3, no. 58 (2018).

- ^Alvarez Tardio, Manuel. "Mobilization and political violence following the Spanish general elections of 1936".Revista de Estudios Politicos177 (2017): 147–179.

- ^Jensen, Geoffrey. Franco. Potomac Books, Inc., 2005, p. 66

- ^Brenan 1950,p. 300.

- ^abBrenan 1950,p. 301.

- ^Preston 1983.

- ^Beevor 2006,pp. 19–39.

- ^Hayes 1965,p. 100.

- ^Rabaté, Jean-Claude; Rabaté, Colette (2009).Miguel de Unamuno: Biografía(in Spanish). Taurus.

- ^"Uneasy path".Evening Post,Volume CXXI, Issue 85, 9 April 1936.Archived2 November 2011 at theWayback MachineNational Library of New Zealand.Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^G., Payne, Stanley (2012).The Spanish Civil War.New York.ISBN978-1107002265.OCLC782994187.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^Beevor 2006,p. 51.

- ^Thomas 2001,pp. 196–198.

- ^Preston 2006,p. 99.

- ^Payne & Palacios 2018,p. 115.

- ^Esdaile, Charles J. The Spanish Civil War: A Military History. Routledge, 2018.

- ^Beevor 2006.

- ^Seidman, Michael. Transatlantic Antifascisms: From the Spanish Civil War to the End of World War II. Cambridge University Press, 2017, p. 17

- ^Payne 2012.

- ^abHayes 1965,p. 103.

- ^Payne 2012,pp. 67–68.

- ^Payne & Palacios 2018,p. 113.

- ^Payne 2011,pp. 89–90.

- ^Payne 2012,pp. 115–125.

- ^Payne 2011,p. 90.

- ^Jensen, Geoffrey (2005).Franco: soldier, commander, dictator(1st ed.). Potomac Books. p. 68.ISBN978-1574886443.

- ^abImperial War Museum(2002)."The Spanish Civil War exhibition: Mainline text"(PDF).Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 11 December 2013.Retrieved27 April2013.

- ^Thomas Barria-Norton,The Spanish Civil War(2001), pp. xviii & 899–901, inclusive.

- ^Time magazine: October 5th, 1936

- ^"La Pasionaria's Farewell Message to the International Brigade fighters".Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2011.Retrieved30 October2010.

- ^"Ángel Viñas, 'La Soledad de la República'".Archived fromthe originalon 30 June 2015.

- ^"Simpson, James"(PDF).

References

[edit]- Beevor, Antony(2006).The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939.New York: Penguin Books.ISBN978-0143037651.

- Brenan, Gerald (1950).The Spanish Labyrinth: an account of the social and political background of the Spanish Civil War.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN0-521-04314-X.

- Casanova, Julián(2010).The Spanish Republic and Civil War.Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511763137.ISBN978-0-521-49388-8.

- Cueva, Julio de la Cueva (1998). "Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War".Journal of Contemporary History.33(3). Sage Publications, Ltd.: 355–369.

- Hayes, Carlton J.H.(1951).The United States and Spain. An Interpretation.Sheed & Ward.ASINB0014JCVS0.

- Payne, Stanley G.(2011) [first published 1987].The Franco regime, 1936–1975.University of Wisconsin Press. p. 90.ISBN978-0299110741.

- Payne, Stanley G.(2012).The Spanish Civil War.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0-521-17470-1.

- Payne, Stanley G.;Palacios, Jesús(2018) [2014].Franco: A Personal and Political Biography(4th ed.).University of Wisconsin Press.ISBN978-0299302146.

- Preston, Paul(2006).The Spanish Civil War: Reaction, Revolution and Revenge(3rd ed.). London:HarperCollins.ISBN978-0-00-723207-9.

- Thomas, Hugh(1977).The Spanish Civil War.Harper & Row.ISBN978-0060142780.

Further reading

[edit]- Álvarez, José E. (2011). "The Spanish Foreign Legion during the Asturian Uprising of October 1934".War in History.18(2): 200–224.doi:10.1177/0968344510393599.ISSN0968-3445.JSTOR26098598.S2CID159593285.

- Beevor, Antony(2006) [1982].The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939.London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.ISBN0-297-84832-1.

- Buckley, Henry (1940).The Life and Death of the Spanish Republic: a Witness to the Spanish Civil War.[ISBN missing]

- Casanova, Julián (2010).The Spanish Republic and Civil War.Cambridge University Press. p. 113.ISBN978-1139490573.

- Graham, Helen(2003).The Spanish Republic at War, 1936–1939.Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-0521459327.

- Hodges, Gabrielle Ashfod (2002).Franco: a concise biography(1st US ed.). St. Martin's Press.ISBN978-0312282851.

- Jackson, Gabriel(1987).The Spanish Republic and the Civil War,1931–1939.Princeton University Press.ISBN978-0691007571.

- Payne, Stanley G.(1987).The Franco Regime.Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.ISBN978-0299110703.

- Payne, Stanley G.(2006).The collapse of the Spanish republic, 1933–1936: Origins of the civil war.Yale University Press.ISBN978-0300110654.

- Payne, Stanley G.(1999).Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977.University of Wisconsin Press.ISBN978-0299165642.

- Payne, Stanley G.(1999).Spain's First Democracy: The Second Republic, 1931–1936.University of Wisconsin Press.ISBN978-0299136741.

- Payne, Stanley G.(2004).The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism.New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.ISBN0-300-10068-X.OCLC186010979.

- Payne, Stanley G.(2008).Franco and Hitler: Spain, Germany, and World War II.New Haven, CT:Yale University Press.ISBN978-0-300-12282-4.

- Preston, Paul(1994)."General Franco as Military Leader"(PDF).Transactions of the Royal Historical Society.4.Cambridge University Press: 21–41.doi:10.2307/3679213.ISSN1474-0648.JSTOR3679213.S2CID153836234.

- Preston, Paul(1995).Franco.Fontana.ISBN978-0-00-686210-9.

- Preston, Paul(2006).The Spanish Civil War: Reaction, Revolution and Revenge(3rd ed.). London:HarperCollins.ISBN978-0-00-723207-9.

- Preston, Paul(2012).The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain(1st ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.ISBN978-0393345919.

- Ruiz, Julius (2015).The 'Red Terror' and the Spanish Civil War: Revolutionary Violence in Madrid.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.ISBN978-1107682931.

- Raymond Carr, ed.The Republic and the Civil War in Spain(1971)[ISBN missing]

- Raymond Carr,Spain 1808–1975(2nd ed. 1982)[ISBN missing]

External links

[edit]- Constitución de la República Española (1931)

- English Translation of the Constitution of the Spanish Republic (1931)

- Second Spanish Republic National AnthemonYouTube

- (in Spanish)Video La II República Española

- Second Spanish Republic

- States and territories established in 1931

- States and territories disestablished in 1939

- Modern history of Spain

- Former republics

- Political history of Spain

- Republicanism in Spain

- 1931 establishments in Spain

- 1939 disestablishments in Spain

- Former countries of the interwar period

- Democratization