Res extensa

| Part ofa serieson |

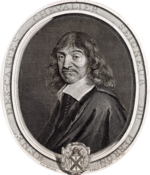

| René Descartes |

|---|

|

Res extensais one of the twosubstancesdescribed byRené Descartesin hisCartesianontology[1](often referred to as "radicaldualism"), alongsideres cogitans.Translated fromLatin,"res extensa"means" extended thing "while the latter is described as" a thinking and unextended thing ".[2]Descartes often translatedres extensaas "corporeal substance" but it is something that only God can create.[3]

Res extensavs.res cogitans[edit]

Res extensaandres cogitansare mutually exclusive and this makes it possible to conceptualize the complete intellectual independence from the body.[2]Res cogitansis also referred to as the soul and is related by thinkers such asAristotlein hisDe Animato the indefinite realm of potentiality.[4]On the other hand,res extensa,are entities described by the principles of logic and are considered in terms of definiteness. Due to the polarity of these two concepts, the natural science focused onres extensa.[4]

In the Cartesian view, the distinction between these two concepts is a methodological necessity driven by a distrust of the senses and theres extensaas it represents the entire material world.[5]The categorical separation of these two, however, caused a problem, which can be demonstrated in this question: How can a wish (a mental event), cause an arm movement (a physical event)?[6]Descartes has not provided any answer to this butGottfried Leibnizproposed that it can be addressed by endowing each geometrical point in theres extensawith mind.[6]Each of these points is withinres extensabut they are also dimensionless, making them unextended.[6]

In Descartes' substance–attribute–mode ontology, extension is the primary attribute of corporeal substance. He describes a piece of wax in the SecondMeditation(seeWax argument). A solid piece of wax has certain sensory qualities. However, when the wax is melted, it loses every single apparent quality it had in its solid form. Still, Descartes recognizes in the melted substance the idea of wax.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Principia Philosophiae,2.001.

- ^abBordo, Susan (2010).Feminist Interpretations of Rene Descartes.University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 59.ISBN978-0271018577.

- ^Schmaltz, Tad (2008).Descartes on Causation.New York: Oxford University Press. pp.46.ISBN9780195327946.

- ^abAerts, Diederik; Chiara, Maria Luisa Dalla; Ronde, Christian de; Krause, Décio (2018).Probing the Meaning of Quantum Mechanics: Information, Contextuality, Relationalism and EntanglementProceedings of the II International Workshop on Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Information. Physical, Philosophical and Logical Approaches.New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing. p. 134.ISBN9789813276888.

- ^Cavell, Richard (2003).McLuhan in Space: A Cultural Geography.Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 83.ISBN0802036104.

- ^abcCallicott, J. Baird (2013).Thinking Like a Planet: The Land Ethic and the Earth Ethic.New York: Oxford University Press. p. 189.ISBN9780199324897.