Revolutionary socialism

| Part ofa serieson |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Revolutionary socialismis apolitical philosophy,doctrine, and tradition withinsocialismthat stresses the idea that asocial revolutionis necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revolution is a necessary precondition for transitioning from acapitalistto asocialist mode of production.Revolution is not necessarily defined as a violent insurrection; it is defined as a seizure of political power by mass movements of theworking classso that thestateis directly controlled or abolished by the working class as opposed to thecapitalist classand its interests.[1]

Revolutionary socialists believe such a state of affairs is a precondition for establishing socialism andorthodox Marxistsbelieve it is inevitable but not predetermined. Revolutionary socialism encompasses multiple political and social movements that may define "revolution" differently from one another. These include movements based on orthodox Marxist theory such asDe Leonism,impossibilismandLuxemburgism,as well as movements based onLeninismand the theory ofvanguardist-led revolution such as theStalinism,Maoism,Marxism–LeninismandTrotskyism.Revolutionary socialism also includes otherMarxist,Marxist-inspired and non-Marxist movements such as those found indemocratic socialism,revolutionary syndicalism,anarchismandsocial democracy.[2]

Revolutionary socialism is contrasted withreformist socialism,especially the reformist wing of social democracy and other evolutionary approaches to socialism. Revolutionary socialism is opposed to social movements that seek to gradually ameliorate capitalism's economic and social problems through political reform.[3]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

This sectionpossibly containssynthesis of materialwhich does notverifiably mentionorrelateto the main topic.(September 2023) |

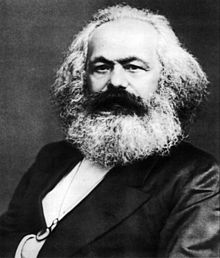

InThe Communist Manifesto,Karl MarxandFriedrich Engelswrote:

The proletariat, the lowest stratum of our present society, cannot stir, cannot raise itself up, without the whole superincumbent strata of official society being sprung into the air. Though not in substance, yet in form, the struggle of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie is at first a national struggle. The proletariat of each country must, of course, first of all settle matters with its own bourgeoisie. In depicting the most general phases of the development of the proletariat, we traced the more or less veiled civil war, raging within existing society, up to the point where that war breaks out into open revolution, and where the violent overthrow of the bourgeoisie lays the foundation for the sway of the proletariat. [...] The Communists fight for the attainment of the immediate aims, for the enforcement of the momentary interests of the working class; [...] The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution.[4]

Twenty-four years afterThe Communist Manifesto,first published in 1848, Marx and Engels admitted that in developed countries, "labour may attain its goal by peaceful means".[5][6]Marxist scholarAdam Schaffargued that Marx, Engels, and Lenin had expressed such views "on many occasions".[7]By contrast, theBlanquistview emphasised the overthrow by force of the ruling elite in government by an active minority of revolutionaries, who then proceeded to implement socialist change, disregarding the state of readiness of society as a whole and the mass of the population in particular for revolutionary change.[citation needed]

In 1875, theSocial Democratic Party of Germany(SPD) published a somewhat reformistGotha Program,which Marx attacked inCritique of the Gotha Program,where he reiterated the need for thedictatorship of the proletariat.The reformist viewpoint was introduced into Marxist thought byEduard Bernstein,one of the leaders of the SPD. From 1896 to 1898, Bernstein published a series of articles entitled "Probleme des Sozialismus" ( "Problems of Socialism" ). These articles led to a debate onrevisionismin the SPD and can be seen as the origins of a reformist trend within Marxism.[citation needed]

In 1900,Rosa LuxemburgwroteSocial Reform or Revolution?,apolemicagainst Bernstein's position. The work of reforms, Luxemburg argued, could only be carried on "in the framework of the social form created by the last revolution". In order to advance society to socialism from the capitalist 'social form', a social revolution will be necessary:

Bernstein, thundering against the conquest of political power as a theory of Blanquist violence, has the misfortune of labeling as a Blanquist error that which has always been the pivot and the motive force of human history. From the first appearance of class societies, having class struggle as the essential content of their history, the conquest of political power has been the aim of all rising classes. Here is the starting point and end of every historic period. [...] In modern times, we see it in the struggle of the bourgeoisie against feudalism.[8][9]

In 1902,Vladimir Leninattacked Bernstein's position in hisWhat Is to Be Done?When Bernstein first put forward his ideas, the majority of the SPD rejected them. The 1899 congress of the SPD reaffirmed theErfurt Program,as did the 1901 congress. The 1903 congress denounced "revisionist efforts".[citation needed]

World War I and Zimmerwald[edit]

On 4 August 1914, the SPD members of the Reichstag voted for the government's war budget, while the French and Belgian socialists publicly supported and joined their governments. TheZimmerwald Conferencein September 1915, attended by Lenin andLeon Trotsky,saw the beginning of the end of the uneasy coexistence of revolutionary socialists and reformist socialists in the parties of theSecond International.The conference adopted a proposal by Trotsky to avoid an immediate split with the Second International. Though initially opposed to it, Lenin voted[10]for Trotsky's resolution to avoid a split among anti-war socialists.

In December 1915 and March 1916, eighteen Social Democratic representatives, theHaase-LedebourGroup, voted against war credits and were expelled from the Social Democratic Party. Liebknecht wroteRevolutionary Socialism in Germanyin 1916, arguing that this group was not a revolutionary socialist group despite their refusal to vote for war credits, further defining in his view what was meant by a revolutionary socialist.[11]

Russian Revolution and aftermath[edit]

| Part ofa serieson |

| Leninism |

|---|

|

Many revolutionary socialists argue that theRussian Revolutionled byVladimir Leninfollows the revolutionary socialist model of a revolutionary movement guided by avanguard party.By contrast, theOctober Revolutionis portrayed as acoup d'étator putsch along the lines ofBlanquism.[citation needed]

Revolutionary socialists, particularly Trotskyists, argue that theBolsheviksonly seized power as the expression of the mass of workers and peasants, whose desires are brought into being by an organised force—the revolutionary party. Marxists such as Trotskyists argue that Lenin did not advocate seizing power until he felt that the majority of the population, represented in thesoviets,demanded revolutionary change and no longer supported the reformist government ofAlexander Kerenskyestablished in the earlier revolution of February 1917. In theLessons of October,Leon Trotskywrote:

Lenin, after the experience of the reconnoiter, withdrew the slogan of the immediate overthrow of the Provisional Government. But he did not withdraw it for any set period of time, for so many weeks or months, but strictly in dependence upon how quickly the revolt of the masses against the conciliationists would grow.[12][non-primary source needed]

For these Marxists, the fact that the Bolsheviks won a majority (in alliance with theLeft Socialist-Revolutionaries) in the second all-Russian congress of Soviets—democratically elected bodies—which convened at the time of the October revolution, shows that they had the popular support of the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, the vast majority of Russian society.[citation needed]

In his pamphletLessons of October,first published in 1924,[13][non-primary source needed]Trotsky argued that military power lay in the hands of the Bolsheviks before the October Revolution was carried out, but this power was not used against the government until the Bolsheviks gained mass support.[citation needed]

The mass of soldiers began to be led by the Bolshevik party after July 1917 and followed only the orders of theMilitary Revolutionary Committeeunder the leadership of Trotsky in October, also termed the Revolutionary Military Committee in Lenin's collected works.[14][non-primary source needed]Trotsky mobilized the Military Revolutionary Committee to seize power on the advent of theSecond All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies,which began on 25 October 1917.[citation needed]

TheCommunist International(also known as the Third International) was founded following theOctober Revolution.This International became widely identified withcommunismbut also defined itself in terms of revolutionary socialism. However, in 1938 Trotskyists formed theFourth Internationalbecause they thought that the Third International turned toMarxism–Leninism—this latter International became identified with revolutionary socialism.Luxemburgismis another revolutionary socialist tradition.[citation needed]

Emerging from the Communist International but critical of the post-1924Soviet Union,the Trotskyist tradition in Western Europe and elsewhere uses the term "revolutionary socialism". In 1932, the first issue of the first Canadian Trotskyist newspaper,The Vanguard,published an editorial entitled "Revolutionary Socialism vs Reformism".[15][non-primary source needed]Today, many Trotskyist groups advocate revolutionary socialism instead of reformism and consider themselves revolutionary socialists. The Committee for a Workers International states, "[w]e campaign for new workers' parties and for them to adopt a socialist programme. At the same time, the CWI builds support for the ideas of revolutionary socialism".[16][non-primary source needed]In "The Case for Revolutionary Socialism", Alex Callinicos from theSocialist Workers Partyin Britain argues in favour of it.[17][non-primary source needed]

Philosophy[edit]

Revolutionary socialist discourse has long debated the question of how the preordained revolution moment would originate, i.e., the extent to which revolt needs to be concertedly organized and by whom.[18]Rosa Luxemburg, in particular, was known for her theory of revolutionary spontaneity.[19][20]Critics argued that Luxemburg overstated the role of spontaneity and neglected the role of party organization.[21]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Thompson, Carl D. (October 1903)."What Revolutionary Socialism Means".The Vanguard.Green Bay: Socialist Party of America.2(2): 13. Retrieved 31 August 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^Kautsky, Karl (1903) [1902].The Social Revolution.Translated by Simons, Algie Martin; Simons, May Wood. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co.Retrieved22 September2020– via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^Cox, Ronald W. (October 2019)."In Defense of Revolutionary Socialism: The Implications of Bhaskar Sunkara's 'The Socialist Manifesto'".Class, Race and Corporate Power.7(2).doi:10.25148/CRCP.7.2.008327.Retrieved22 September2020– via ResearchGate.

- ^Engels, Friedrich; Marx, Karl (1969) [1848].The Communist Manifesto."Chapter I. Bourgeois and Proletarians".Marx/Engels Collected Works.I.Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 98–137. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^Engels, Friedrich; Marx, Karl (187 September 1872)."La Liberté Speech".The Hague Congress of the International. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive. "[W]e do not deny that there are countries like England and America, [...] where labour may attain its goal by peaceful means."

- ^Engels, Friedrich, Marx, Karl (1962).Karl Marx and Frederick Engels on Britain.Moscow: Foreign Languages Press.

- ^Schaff, Adam (April–June 1973). "Marxist Theory on Revolution and Violence".Journal of the History of Ideas.University Press of Pennsylvania.34(2): 263–270.doi:10.2307/2708729.JSTOR2708729."Both Marx and Engels and, later, Lenin on many occasions referred to apeacefulrevolution, that is, one attained by a class struggle, but not by violence. "

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa (1986) [1900].Social Reform or Revolution?"Chapter 8: Conquest of Political Power".London: Militant Publications. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^Luxemburg, Rosa (1970).Rosa Luxemburg Speaks(2nd ed). Pathfinder. pp. 107–108.ISBN978-0873481465.

- ^Fagan, Guy (1980).Biographical Introduction to Christian Rakovsky, Selected Writings on Opposition in the USSR 1923–30(1st ed.). London and New York: Allison & Busby and Schocken Books.ISBN978-0850313796.Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^Liebknecht, Karl (1916)."Revolutionary Socialism in Germany".In Fraina, Louis C., ed. (1919).The Social Revolution in Germany.The Revolutionary Age Publishers. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^Trotsky, Leon (1937) [1924].Lessons of October."Chapter Four: The April Conference".Translated by Wright, John. G. New York: Pioneer Publishers. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^Trotsky, Leon (1937) [1924].Lessons of October.Translated by Wright, John. G. New York: Pioneer Publishers. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^Trotsky, Leon.Lessons of October."Chapter Six: On the Eve of the October Revolution – the Aftermath".Translated by Wright, John. G. New York: Pioneer Publishers. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Marxist Internet Archive. "On October 16th the Military Revolutionary Committee was created, the legal Soviet organ of insurrection."

- ^"Revolutionary Socialism vs Reformism".The Vanguard(1). 1932. Retrieved 22 September 2020 – via the Socialist History Project.

- ^[1].Committee for a Workers International.Archived27 September 2007 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 27 September 2007 – via theSocialist World.

- ^Callinicos, Alex (7 December 2003)."The Case for Revolutionary Socialism".Socialist Workers Party.Archived28 September 2007 at theWayback Machine.Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^Gandio, Jason Del; Thompson, A. K. (2017-08-28).Spontaneous Combustion: The Eros Effect and Global Revolution.SUNY Press.ISBN978-1-4384-6727-6.

- ^Talmon, Jacob L. (1991).Myth of the Nation and Vision of Revolution: Ideological Polarization in the Twentieth Century.Routledge.p. 70.ISBN9781412848992.

- ^Guérin, Daniel (2017).For a Libertarian Communism.PM Press. p. 75.ISBN978-1-62963-236-0.

- ^Nowak, Leszek; Paprzycki, Marcin (1993).Social System, Rationality and Revolution.Rodopi.ISBN978-90-5183-560-1.