Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter | |

|---|---|

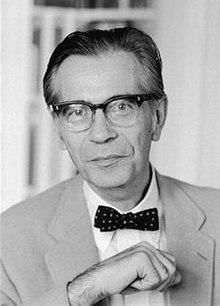

Hofstadter circa 1970 | |

| Born | August 6, 1916 Buffalo, New York,U.S. |

| Died | October 24, 1970(aged 54) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Spouses |

|

| Awards | Pulitzer Prize(1956, 1964) |

| Academic background | |

| Education | |

| Doctoral advisor | Merle Curti |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | History |

| Sub-discipline | American history |

| Institutions | Columbia University |

| Doctoral students | |

| Notable students | |

| Main interests | History ofAmerican political culture |

| Notable works | |

| Influenced | |

Richard Hofstadter(August 6, 1916 – October 24, 1970) was an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century. Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History atColumbia University.Rejecting his earlierhistorical materialistapproach to history, in the 1950s he came closer to the concept of "consensus history",and was epitomized by some of his admirers as the" iconic historian of postwar liberal consensus. "[5]Others see in his work an early critique of theone-dimensional society,as Hofstadter was equally critical of socialist and capitalist models of society, and bemoaned the "consensus" within the society as "bounded by the horizons of property and entrepreneurship",[5]criticizing the "hegemonic liberal capitalist culture running throughout the course of American history".[6]

His most widely read works areSocial Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915(1944);The American Political Tradition(1948);The Age of Reform(1955);Anti-intellectualism in American Life(1963); and the essays collected inThe Paranoid Style in American Politics(1964). He was twice awarded thePulitzer Prize:in 1956 forThe Age of Reform,an analysis of thepopulism movement in the 1890sand theprogressive movement of the early 20th century;and in 1964 for the cultural historyAnti-intellectualism in American Life.[7]He was an elected member of theAmerican Academy of Arts and Sciences[8]and theAmerican Philosophical Society.[9]

Early life and education

[edit]Hofstadter was born inBuffalo, New York,in 1916 to a Jewish father, Emil A. Hofstadter, and aGerman-AmericanLutheran mother, Katherine (née Hill), who died when Richard was ten.[10]He attendedFosdick-Masten Park High Schoolin Buffalo. Hofstadter then studied philosophy and history at theUniversity at Buffalo,from 1933, under thediplomatic historianJulius W. Pratt.Despite opposition from both families, he married Felice Swados (whose brother wasHarvey Swados)[11]in 1936 after he and Felice spent several summers at Hunter Colony, New York, run byMargaret Lefranc,their close friend for years; they had one child, Dan.[12]

Hofstadter was raised as anEpiscopalianbut later identified more with his Jewish roots.Antisemitismmay have cost him fellowships atColumbiaand attractive professorships.[13]TheBuffalo Jewish Hall of Famelists him as one of the "Jewish Buffalonians who have made a lasting contribution to the world."[14]

In 1936, Hofstadter entered the doctoral program in history atColumbia Universitywhere his advisorMerle Curtiwas demonstrating how to synthesize intellectual, social, and political history based upon secondary sources rather than primary-source archival research.[15]In 1938, he became a member of theCommunist Party USA,but soon became disillusioned by theStalinistparty disciplineandshow trials.After withdrawing from the party in August 1939 following theHitler–Stalin Pact,he retained a critical left-wing perspective that was still obvious inAmerican Political Traditionin 1948.[16]

Hofstadter earned his PhD in 1942. In 1944, he published his dissertationSocial Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915.It was a commercially successful (200,000 copies) critique of late-19th-century American capitalism and its ruthless "dog-eat-dog" economic competition andSocial Darwinianself-justification. Conservative critics, such asIrwin G. WylieandRobert C. Bannister,disagreed with his interpretation.[17][18][19]The sharpest criticism of the book focused on Hofstadter's weakness as a researcher: "he did little or no research into manuscripts, newspapers,archival,or unpublished sources, relying instead primarily on secondary sources augmented by his lively style and wide-ranging interdisciplinary readings, thereby producing well-written arguments based on scattered evidence he found by reading other historians. "[20]

From 1942 to 1946, Hofstadter taught history at theUniversity of Maryland,where he became a close friend of the popular sociologistC. Wright Millsand read extensively in the fields of sociology and psychology, absorbing ideas ofMax Weber,Karl Mannheim,Sigmund Freud,and theFrankfurt School.His later books frequently refer to behavioral concepts such as "status anxiety".[21][22]

Assessment as a "consensus historian"

[edit]In 1946, Hofstadter joinedColumbia University's faculty, and in 1959 he succeededAllan Nevinsas the DeWitt Clinton Professor ofAmerican History,where he played a major role in directing Ph.D. dissertations. According to his biographer David Brown, after 1945 Hofstadter philosophically "broke" withCharles A. Beardand moved to the right, becoming leader of the "consensus historians," a term Hofstadter disapproved of, but that was widely applied to his apparent rejection of the Beardian idea that the sole basis for understanding American history is the fundamental conflict between economic classes.[23]

In a widely held revision of this view,Christopher Laschwrote that, unlike the "consensus historians" of the 1950s, Hofstadter saw the consensus of classes on behalf of business interests not as a strength but "as a form of intellectual bankruptcy and as a reflection, moreover, not of a healthy sense of the practical but of the domination of American political thought by popular mythologies."[24]

As early as hisAmerican Political Tradition(1948), while still viewing politics from a critical left-wing perspective, Hofstadter rejected black-and-white polarization between pro-business and anti-business politicians.[25]Making explicit reference toJefferson,Jackson,Lincoln,Cleveland,Bryan,Wilson,andHoover,Hofstadter made a statement on the consensus in the American political tradition that has been seen as "ironic". He said:[26]

The fierceness of the political struggles has often been misleading: for the range of vision embraced by the primary contestants in the major parties has always been bounded by the horizons of property and enterprise. However much at odds on specific issues, the major political traditions have shared a belief in therights of property,the philosophy ofeconomic individualism,the value of competition; they have accepted the economic virtues of capitalist culture as necessary qualities of man.[27]

Hofstadter later complained that this remark in a hastily written preface requested by the editor had been the reason for "lumping him" unfairly into the category of "consensus historians" likeBoorstin,who celebrated this kind of ideological consensus as an achievement, whereas Hofstadter deplored it.[28]Hofstadter expressed his dislike of the termconsensus historianseveral times,[29]and criticized Boorstin for overusing the consensus and ignoring the essential conflicts in history.[30]In an earlier draft of the preface, he wrote:[31]

American politics has always been an arena in which conflicts of interests have been fought out, compromised, adjusted. Once these interests were sectional; now they tend more clearly to follow class lines; but from the beginning American political parties, instead of representing single sections or classes clearly and forcefully, have been intersectional and interclass parties, embracing a jumble of interests which often have reasons for contesting among themselves.

Hofstadter rejected Beard's interpretation of history as a succession of exclusively economically motivated group conflicts and financial interests of politicians. He thought that most of the periods of US history, except theCivil War,could be fully understood only by taking into account an implicit consensus, shared by all groups across the conflict lines. He criticized the generation of Beard andVernon Louis Parringtonbecause they had

put such an excessive emphasis on conflict, that an antidote was needed.... It seems to me to be clear that a political society cannot hang together, at all, unless there is some kind of consensus running through it, and yet that no society has such a total consensus as to be devoid of significant conflict. It is all a matter of proportion and emphasis, which is terribly important in history. Of course, obviously, we have had one total failure of consensus, which led to the Civil War. One could use that as the extreme case in which consensus breaks down.[32]

In 1948 he publishedThe American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It,interpretive studies of 12 major American political leaders from the 18th to the 20th centuries. The book was a critical success and sold nearly a million copies at university campuses, where it was used as a history textbook; critics found it "skeptical, fresh,revisionary,occasionally ironical, without being harsh or merely destructive. "[33]Each chapter title illustrated a paradox:Thomas Jeffersonis "The Aristocrat as Democrat";John C. Calhounis the "Marx of the Master Class"; andFranklin Rooseveltis "The Patrician as Opportunist".[34]In writing the book, Hofstadter was influenced by literary figures as well as historians: two key influences on him were the critic Edmund Wilson and the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald.[35]Hofstadter's style was so powerful and engrossing that professors kept assigning the book long after scholars had revised or rejected its main points.[36]

On April 13, 1970, less than a year before his death, Hofstadter wrote historianBernard Bailyn,expressing concerns about scholarly depictions of recent studies by both of them as "consensus." Bailyn's response has not yet been examined by third-party sources.[37]

Later works

[edit]As a historian, Hofstadter's groundbreaking work came in using social psychology concepts to explain political history.[a]He exploredsubconsciousmotives such associal statusanxiety,anti-intellectualism,irrational fear, andparanoiaas they propel political discourse and action in politics. HistorianLloyd Gardnerwrote that "in later essays Hofstadter specifically ruled out the possibility of a Leninist interpretation of American imperialism."[39]

Rural ethos

[edit]The Age of Reform(1955) analyzes theyeomanideal in America's sentimental attachment toagrarianismand the farm's moral superiority to the city. Hofstadter—himself very much a big-city person—noted theagrarianethos was "a kind of homage that Americans have paid to the fancied innocence of their origins; however, to call it a myth does not imply falsity, because it effectively embodies the rural values of the American people, profoundly influencing their perception of the correct values, hence their political behavior." In this matter, the stress is on the importance of Jefferson's writings, and of his followers, in the development of agrarianism in the US, as establishing the agrarian myth, and its importance, in American life and politics—despite the rural and urban industrialization that rendered the myth moot.[40][page needed]

Anti-intellectualism in American Life(1963) andThe Paranoid Style in American Politics(1965) describe Americanprovincialism,warning againstanti-intellectualfear of thecosmopolitancity, presented as wicked by thexenophobicandanti-SemiticPopulistsof the 1890s. They trace the direct political and ideological lineage between the Populists andanti-communistSenatorJoseph McCarthyandMcCarthyism,the political paranoia manifest in his time. Hofstadter's dissertation directorMerle Curtiwrote that Hofstadter's "position is as biased, by his urban background... as the work of older historians was biased by their rural background and traditional agrarian sympathies.”[41]

Irrational fear

[edit]The Idea of a Party System(1969) describes the origins of theFirst Party Systemas reflecting fears that the (other) political party threatened to destroy the republic.The Progressive Historians: Turner, Beard, Parrington(1968) systematically analyzes and criticizes the intellectual foundations and historical validity of Beard'shistoriographyand revealed Hofstadter's increasing inclination towardneoconservatism.Privately, Hofstadter said thatFrederick Jackson Turnerwas no longer a useful guide to history, because he was too obsessed with the frontier and his ideas too often had "a pound of falsehood for every few ounces of truth."[b]

Howe and Finn argue that, rhetorically, Hofstadter's cultural interpretation repeatedly drew upon concepts from literary criticism ( "irony," "paradox," "anomaly" ), anthropology ( "myth," "tradition," "legend," "folklore"), and social psychology (" projection, "" unconsciously, "" identity, "" anxiety, "" paranoid "). He artfully employed their explicit scholarly meanings and their informal prejudicial connotations. His goal, they argue, was" destroying certain cherished American traditions and myths derived from his conviction that they provided no trustworthy guide for action in the present. "[43]Thus Hofstadter argued, "The application of depth psychology to politics, chancy though it is, has at least made us acutely aware that politics can be a projective arena for feelings and impulses that are only marginally related to the manifest issues."[44]C. Vann Woodwardwrote that Hofstadter seemed "to have a solid understanding, if not a private affection" for "the odd, the warped, the 'zanies' and the crazies of American life—left, right and middle."[45]

Political views

[edit]Influenced by his wife, Hofstadter was a member of theYoung Communist Leaguein college, and in April 1938 he joined theCommunist Party USA;he quit in 1939.[46]Hofstadter had been reluctant to join, knowing the orthodoxy it imposed on intellectuals, telling them what to believe and what to write. He was disillusioned by the spectacle of theMoscow Show Trials,but wrote: "I join without enthusiasm but with a sense of obligation.... [M]y fundamental reason for joining is that I don't like capitalism and want to get rid of it."[47]He remainedanti-capitalist,writing, "I hate capitalism and everything that goes with it," but was similarly disillusioned withStalinism,finding the Soviet Union "essentially undemocratic" and the Communist Party rigid and doctrinaire. In the 1940s, Hofstadter abandoned political causes, feeling that intellectuals were no more likely to "find a comfortable home" under socialism than they were under capitalism.[47][48]

BiographerSusan Bakerwrites that Hofstadter "was profoundly influenced by the political Left of the 1930s.... The philosophical impact of Marxism was so intense and direct during Hofstadter's formative years that it formed a major part of his identity crisis.... The impact of these years created his orientation to the American past, accompanied as it was by marriage, establishment of life-style, and choice of profession."[49]Geary concludes that, "To Hofstadter, radicalism always offered more of a critical intellectual stance than a commitment to political activism. Although Hofstadter quickly became disillusioned with the Communist Party, he retained an independent left-wing standpoint well into the 1940s. His first book,Social Darwinism in American Thought(1944), andThe American Political Tradition(1948) had a radical point of view. "[50]

In the 1940s, Hofstadter cited Beard as "the exciting influence on me".[51]Hofstadter specifically responded to Beard's social-conflict model of U.S. history, which emphasized the struggle among competing economic groups (primarily farmers, Southern slavers, Northern industrialists, and workers) and discounted abstract political rhetoric that rarely translated into action. Beard encouraged historians to search for economic belligerents' hidden self-interest and financial goals. By the 1950s and 1960s, Hofstadter had a strong reputation in liberal circles.Lawrence Creminwrote that "Hofstadter's central purpose in writing history... was to reformulate American liberalism so that it might stand more honestly and effectively against attacks from both left and right in a world which had accepted the essential insights ofDarwin,Marx,andFreud."[52]Alfred Kazinidentified his use of parody: "He was a derisive critic and parodist of every American Utopia and its wild prophets, a natural oppositionist to fashion and its satirist, a creature suspended between gloom and fun, between disdain for the expected and mad parody."[53]

In 2008, conservative commentatorGeorge Willcalled Hofstadter "the iconic public intellectual of liberal condescension" who "dismissed conservatives as victims of character flaws and psychological disorders—a 'paranoid style' of politics rooted in 'status anxiety.' etc. Conservatism rose on a tide of votes cast by people irritated by the liberalism of condescension."[54]

Later life

[edit]Angered by the radical politics of the 1960s, and especially by thestudent occupation and temporary closure of Columbia University in 1968,Hofstadter began to criticize student activist methods. His friendDavid Herbert Donaldsaid, "as a liberal who criticized the liberal tradition from within, he was appalled by the growing radical, even revolutionary, sentiment that he sensed among his colleagues and his students. He could never share their simplistic, moralistic approach."[55]Brick says he regarded them as "simple-minded, moralistic, ruthless, and destructive."[56]Moreover, he was "extremely critical of student tactics, believing that they were based on irrational romantic ideas, rather than sensible plans for achievable change, that they undermined the unique status of the university, as an institutional bastion of free thought, and that they were bound to provoke a political reaction from the right."[57]Coates argues that his career saw a steady move from left to right, and that his 1968 Columbiacommencement address"represented the completion of his conversion to conservatism".[58]

Despite strongly disagreeing with their political methods, he invited his radical students to discuss goals and strategy with him. He even employed one,Mike Wallace,to collaborate with him onAmerican Violence: A Documentary History(1970); Hofstadter studentEric Fonersaid the book "utterly contradicted the consensus vision of a nation placidly evolving without serious disagreements."[59]

Hofstadter planned to write a three-volume history of American society. At his death, he had only completed the first volume,America at 1750: A Social Portrait(1971).

Death and legacy

[edit]Hofstadter died ofleukemiaon October 24, 1970, atMount Sinai HospitalinManhattan,at age 54.[60]He showed more interest in his research than in his teaching. In undergraduate classes, he read aloud the draft of his next book.[61]As a senior professor at a leadinggraduate university,Hofstadter directed more than 100 finisheddoctoral dissertationsbut gave his graduate students only cursory attention; he believed this academic latitude enabled them to find their own models of history. Among them wereHerbert Gutman,Eric Foner,Lawrence W. Levine,Linda Kerber,andPaula S. Fass.Some, such asEric McKitrickandStanley Elkins,were more conservative than he; Hofstadter had few disciples and founded no school of history writing.[62][63]

Following Hofstadter's death, Columbia dedicated a locked bookcase of his works inButler Libraryto him. When the library's physical conditions deteriorated, his widow Beatrice—who later married the journalistTheodore White—asked that it be removed.

Published works

[edit]- "The Tariff Issue on the Eve of the Civil War,"The American Historical ReviewVol. 44, No. 1 (Oct. 1938), pp. 50–55full text in JSTOR

- "William Graham Sumner, Social Darwinist,"The New England QuarterlyVol. 14, No. 3 (Sep. 1941), pp. 457–77online at JSTOR

- "Parrington and the Jeffersonian Tradition,"Journal of the History of IdeasVol. 2, No. 4 (Oct. 1941), pp. 391–400JSTOR

- "William Leggett, Spokesman of Jacksonian Democracy,"Political Science QuarterlyVol. 58, No. 4 (Dec. 1943), pp. 581–94JSTOR

- Hofstadter, Richard (April 1944), "UB Phillips and The Plantation Legend",The Journal of Negro History,29(2): 109–24,doi:10.2307/2715306,JSTOR2715306,S2CID150112096.

- Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915,Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992 [1944],ISBN978-0-8070-5503-8;[64]online

- The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It(New York: A. A. Knopf, 1948).online

- "Beard and the Constitution: The History of an Idea,"American Quarterly(1950) 2#3 pp. 195–213JSTOR

- The Age of Reform:from Bryan to FDR(New York: Knopf, 1955).

- The Development of Academic Freedom in the United States(New York: Columbia University Press, 1955) with Walter P. MetzgerOCLC175391online

- Hofstadter's contribution was published separately asAcademic Freedom in the Age of the College,Columbia University Press, [1955] 1961.

- The United States: the History of a Republic(Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1957), college textbook; several editions; coauthored with Daniel Aaron and William Miller

- Anti-intellectualism in American Life(New York: Knopf, 1963).online

- The Progressive Movement, 1900–1915(Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963). edited excerpts.OCLC265628

- Hofstadter, Richard (October 8, 1964)."A Long View: Goldwater in History".New York Review of Books.3(4).

- The Paranoid Style in American Politics, and Other Essays(New York: Knopf, 1965).ISBN978-0-226-34817-9online

- includes "The Paranoid Style in American Politics",Harper's Magazine(1964)

- The Progressive Historians: Turner, Beard, Parrington(New York: Knopf, 1968)online.

- The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780–1840(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969).online

- American Violence: A Documentary History,co-edited withMike Wallace(1970)ISBN978-0-394-41486-7

- "America As A Gun Culture "American Heritage,21 (October 1970), 4–10, 82–85.

- America at 1750: A Social Portrait(1971)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^He was influenced by his friend sociologistC. Wright Mills.[38]

- ^The private letter was written toMerle Curti,probably in 1948.[42]

References

[edit]- ^"Lawrence W. Levine (1933-2006) | Perspectives on History | AHA".

- ^"Richard D. Heffner '46, '47 GSAS, Host of Public Television's Open Mind | Columbia College Today".

- ^Katznelson, Ira (May 11, 2021)."Measuring Liberalism, Confronting Evil: A Retrospective".Annual Review of Political Science.24(1): 1–19.doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-042219-030219.ISSN1094-2939.

- ^Italie, Hillel (April 6, 2013)."Robert Remini Dies, Leaves Legacy as Andrew Jackson Scholar".The Christian Science Monitor.Boston, Massachusetts: Christian Science Publishing Society. Associated Press.RetrievedNovember 19,2019.

- ^abGeary (2007), p. 429

- ^Geary, Dan (April 14, 2009).Radical Ambition: C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought.University of California Press. pp.126.ISBN9780520943445.

C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought, which sharply criticized.

- ^Benét (1996),Reader's Encyclopedia(4th ed.), p. 478.

- ^"Richard Hofstadter".American Academy of Arts & Sciences.RetrievedDecember 21,2022.

- ^"APS Member History".search.amphilsoc.org.RetrievedDecember 21,2022.

- ^Ohles, Frederik; Ohles, Shirley G.; Ohles, Shirley M.; Ramsay, John G. (1997),Books,Bloomsbury Academic,ISBN9780313291333

- ^Brown 2006,p. 9.

- ^Brown 2006,pp. 18–19.

- ^Brown 2006,pp. 12, 21, 38, 53.

- ^SeeBuffalo Jewish Hall of Fame

- ^Brown 2006,pp. 22, 29.

- ^Reviewed Work: Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography by David S. Brown. Review by: Daniel Geary, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Sept. 2007), pp. 425–431 (7 pages) Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

- ^Brown 2006,pp. 30–37.

- ^Wylie, Irwin G (1959), "Social Darwinism and the Businessmen",Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society,103:629–35.

- ^Bannister, Robert C (1989),Social Darwinism: Science and Myth in Anglo–American Social Thought.

- ^Brown 2006,pp. 38, 113.

- ^Baker 1985,p. 184.

- ^Brown 2006,pp. 90–94.

- ^Brown (2006), p. 75

- ^Lasch, Christopher (March 8, 1973)."On Richard Hofstadter".The New York Review of Books.ISSN0028-7504.RetrievedDecember 29,2018.

- ^Neil Jumonville,Henry Steele Commager: Midcentury Liberalism and the History of the Present(1999) pp. 232–39

- ^Kraus, Michael; Joyce, Davis D. (January 1, 1990).The Writing of American History.University of Oklahoma Press. p. 318.ISBN9780806122342.

- ^Richard Hofstadter (1948).The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made it.Knopf. pp. xxxvi–xxxvii.ISBN9780307809667.

- ^Palmer, William (January 13, 2015).Engagement with the Past: The Lives and Works of the World War II Generation of Historians.University Press of Kentucky. p. 186.ISBN9780813159270.

- ^Rushdy, Ashraf H. A. (November 4, 1999).Neo-slave Narratives: Studies in the Social Logic of a Literary Form.Oxford University Press. p. 129.ISBN9780198029007.

- ^Kraus, Michael; Joyce, Davis D. (January 1, 1990).The Writing of American History.University of Oklahoma Press.ISBN9780806122342.

- ^Archived6 August 2020 at theWayback Machine[dead link]

- ^In Pole (2000), pp. 73–74

- ^Pole (2000), p. 71

- ^Kuklick, Bruce (2006), "Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography (review)",Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society,42(4): 574–77,doi:10.1353/csp.2007.0005,S2CID162307620.

- ^Witham, Nick (2023).Popularizing the Past: Historians, Publishers, and Readers in Postwar America.University of Chicago Press. pp. 42–3.ISBN9780226826998.

- ^Pole (2000), pp. 71–72.

- ^Kammen, Michael G. (1987).Selvages & Biases: The Fabric of History in American Culture.Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 129.ISBN9780801494048.

- ^Brown (2006), p. 93

- ^Lloyd C. Gardner, "Consensus history and foreign policy." in Alexander DeConde, ed.Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy(1978) 1:159.

- ^Hofstadter, Richard (1955),The Age of Reform

- ^In Brown (2006), p. 112

- ^Brown (2003), p. 531.

- ^Howe; Finn,Richard Hofstadter: The Ironies of an American Historian,pp. 3–5, 6.

- ^Hofstadter, Richard; Wilentz, Sean (2008).The Paranoid Style in American Politics.Random House Digital. p. xxxiii.ISBN9780307388445.

- ^Quoted in John Wakeman, World Authors 1950–1970: A Companion Volume to Twentieth Century Authors.New York: H.W. Wilson Company, 1975.ISBN0824204190.(pp. 658–60).

- ^Baker 1985,pp. 89–90.

- ^abFoner, Eric(2003).Who Owns History?: Rethinking the Past in a Changing World.Macmillan. p. 38.ISBN9781429923927.

- ^Geary (2007), p. 429.

- ^Baker, Susan Stout (1982),Out of the Engagement: Richard Hofstadter, the Genesis of a Historian(PhD dissertation), Case Western Reserve U, p. xiv,OCLC10169852.

- ^Geary (2007), p. 418.

- ^Foner, 1992

- ^Lawrence Arthur Cremin(1972).Richard Hofstadter (1916–1970): a biographical memoir.National Academy of Education.p. x.

- ^Alfred Kazin (2013).New York Jew.Knopf Doubleday. p. 25.ISBN9780804151269.

- ^Candidate on a High Horse,George Will,The Washington Post,April 15, 2008.

- ^In Brown (2006), p. 180

- ^Howard Brick, "The End of Ideology Thesis." inThe Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies(2013) p 103

- ^Geary (2007), p. 430.

- ^Ryan Coates, "The Conservatism of Richard Hofstadter,"History in the Making(2013) 2#1 pp 45–51 quote at p 50onlineArchivedJune 8, 2015, at theWayback Machine

- ^Foner, Eric,Introduction,p. xxv,inHofstadter 1992

- ^Alden Whitman(October 25, 1970)."Richard Hofstadter, Pulitzer Historian, 54, Dies. Author of 13 Books Received Prizes for '55 and '64".The New York Times.RetrievedDecember 15,2014.

Richard Hofstadter, one of the leading historians of American affairs, died yesterday of leukemia at Mount Sinai Hospital at the age of 54. He was DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University and twice a Pulitzer Prize-winner. He lived at 1125 Park Avenue.

- ^Brown (2006), p. 66

- ^Brown (2006), pp. 66–71.

- ^Kazin (1999), p. 343

- ^Bowers, David F.(1945)."Social Darwnism in American Thought, 1860-1915(Book Review) ".Pacific Historical Review.14(1): 103.doi:10.2307/3634537.JSTOR3634537.

Further reading

[edit]- Baker, Susan Stout (1985),Radical Beginnings: Richard Hofstadter and the 1930s.

- Brick, Howard. "The End of Ideology Thesis." inThe Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies(2013) pp: 90+

- Brinkley, Alan (September 1985). "Richard Hofstadter'sThe Age of Reform:A Reconsideration ".Reviews in American History.13(3): 462–80.doi:10.2307/2702106.JSTOR2702106.

- Brown, David S(2006),Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography(biography), U. of Chicago,ISBN9780226076379

- Brown, David S.(August 2003). "Redefining American History: Ethnicity, Progressive Historiography and the Making of Richard Hofstadter".The History Teacher.36(4): 527–48.doi:10.2307/1555578.JSTOR1555578.

- Claussen, Dane S (2004),Anti-Intellectualism in American Media,New York: Peter Lang.

- Collins, Robert M. (June 1989). "The Originality Trap: Richard Hofstadter on Populism".The Journal of American History.76(1): 150–67.doi:10.2307/1908347.JSTOR1908347.

- Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1974), "Richard Hofstadter: A Progress",The Hofstadter Aegis,Knopf, pp. 300–67.

- Foner, Eric,"The Education of Richard Hofstadter",The Nation,254(May 17, 1992): 597+.

- Geary, Daniel (2007). "Richard Hofstadter Reconsidered".Reviews in American History.35(3): 425–31.doi:10.1353/rah.2007.0052.S2CID145240475.

- Greenberg, David (Fall 2007). "Richard Hofstadter Reconsidered".Raritan Review.27(2): 144–67..

- Guelzo, Allen C (January–February 2007), "History with a Smirk: Richard Hofstadter and scholarly fashion",Books and Culture,Christianity Today.

- Harp, Gillis. "Hofstadter's 'The Age of Reform' and the Crucible of the Fifties,"Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era6#2 (2007): 139–48in JSTOR

- Howe, Daniel Walker; Finn, Peter Elliott (February 1974). "Richard Hofstadter: The Ironies of an American Historian".Pacific Historical Review.43(1): 1–23.doi:10.2307/3637588.JSTOR3637588.

- Johnston, Robert D."The Age of Reform": A Defense of Richard Hofstadter Fifty Years On, "Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era6#2 (2007), pp. 127–137in JSTOR

- Kazin, Michael (1999). "Hofstadter Lives: Political Culture and Temperament in the Work of an American Historian".Reviews in American History.27(2): 334–48.doi:10.1353/rah.1999.0039.S2CID144903023.

- Leonard, Thomas C (2009)."Origins of the Myth of Social Darwinism: The Ambiguous Legacy of Richard Hofstadter'sSocial Darwinism in American Thought"(PDF).Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization.71:37–51.doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2007.11.004.S2CID7001453.

- Marx, Leo. 1964. The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McKenzie-McHarg, Andrew. "From Status Politics to the Paranoid Style: Richard Hofstadter and the Pitfalls of Psychologizing History."Journal of the History of Ideas83.3 (2022): 451–475.

- Pole, Jack (2000). "Richard Hofstadter". In Rutland, Robert Allen (ed.).Clio's Favorites: Leading Historians of the United States, 1945–2000.University of Missouri Press. pp.68–83.ISBN9780826213167.

- Scheiber, Harry N (September 1974). "A Keen Sense of History and the Need to Act: Reflections on Richard Hofstadter and the American Political Tradition".Reviews in American History.2(3): 445–52.doi:10.2307/2701207.JSTOR2701207.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. (1969)."Richard Hofstadter".In Cunliffe, Marcus; Winks, Robin (eds.).Pastmasters: Some Essays on American Historians.pp.278–315.

- Serby, Benjamin.Richard Hofstadter at 100,an online exhibition featuring archival materials from Hofstadter's collected papers at Columbia University.

- Singal, Daniel Joseph (October 1984). "Beyond Consensus: Richard Hofstadter and American Historiography".The American Historical Review.89(4): 976–1004.doi:10.2307/1866401.JSTOR1866401.

- Ward, John William1955. Andrew Jackson, Symbol for an Age. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ward, John William1969 Red, White, and Blue: Men, Books, and Ideas in American Culture. New York: Oxford University Press

- Wiener, Jon(October 5, 2006),"America, Through A Glass Darkly",The Nation.

- Witham, Nick (2023).Popularizing the Past: Historians, Publishers, and Readers in Postwar America.University of Chicago Press.

External links

[edit] Quotations related toRichard Hofstadterat Wikiquote

Quotations related toRichard Hofstadterat Wikiquote

- 1916 births

- 1970 deaths

- Historians of the United States

- Historiographers

- Jewish American historians

- Populism scholars

- American anti-fascists

- American anti-capitalists

- New York (state) socialists

- American people of German descent

- American people of German-Jewish descent

- Left-wing politics in the United States

- Pulitzer Prize for History winners

- Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction winners

- Columbia University faculty

- Columbia Graduate School of Arts and Sciences alumni

- University of Maryland, College Park faculty

- Writers from Buffalo, New York

- University at Buffalo alumni

- 20th-century American historians

- Academics of the University of Cambridge

- Deaths from leukemia in New York (state)

- 20th-century American male writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- Historians from New York (state)

- 20th-century American Jews

- Members of the American Philosophical Society