Rune

| Runic ᚱᚢᚾᛁᚲ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | Alphabet

|

Time period | Elder Futharkfrom the 2nd century AD |

| Direction | Left-to-right,boustrophedon |

| Languages | Germanic languages |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Elder Futhark,Younger Futhark,Anglo-Saxon futhorc |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Runr(211),Runic |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Runic |

| U+16A0–U+16FF[2] | |

Aruneis aletterin a set of relatedalphabetsknown asrunic alphabetsnative to theGermanic peoples.Runes were used to writeGermanic languages(with some exceptions) before they adopted theLatin alphabet,and for specialised purposes thereafter. In addition to representing a sound value (aphoneme), runes can be used to represent the concepts after which they are named (ideographs). Scholars refer to instances of the latter asBegriffsrunen('concept runes'). The Scandinavian variants are also known asfuþark,orfuthark;this name is derived from the first six letters of the script, ⟨ᚠ⟩, ⟨ᚢ⟩, ⟨ᚦ⟩, ⟨ᚨ⟩/⟨ᚬ⟩, ⟨ᚱ⟩, and ⟨ᚲ⟩/⟨ᚴ⟩, corresponding to the Latin letters ⟨f⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨þ⟩/⟨th⟩, ⟨a⟩, ⟨r⟩, and ⟨k⟩. TheAnglo-Saxonvariant is known asfuthorc,orfuþorc,due to changes inOld Englishof the sounds represented by the fourth letter, ⟨ᚨ⟩/⟨ᚩ⟩.

Runologyis the academic study of the runic alphabets,runic inscriptions,runestones,and their history. Runology forms a specialised branch ofGermanic philology.

The earliest secure runic inscriptions date from around AD 150, with a potentially earlier inscription dating to AD 50 andTacitus's potential description of rune use from around AD 98. TheSvingerud Runestonedates from between AD 1 and 250. Runes were generally replaced by theLatin alphabetas the cultures that had used runes underwentChristianisation,by approximately AD 700 in central Europe and 1100 innorthern Europe.However, the use of runes persisted for specialized purposes beyond this period. Up until the early 20th century, runes were still used in ruralSwedenfor decorative purposes inDalarnaand onrunic calendars.

The three best-known runic alphabets are theElder Futhark(c.AD 150–800), theAnglo-Saxon Futhorc(400–1100), and theYounger Futhark(800–1100). The Younger Futhark is divided further into the long-branch runes (also calledDanish,although they were also used inNorway,Sweden,andFrisia); short-branch, orRök,runes (also calledSwedish–Norwegian,although they were also used inDenmark); and thestavlösa,or Hälsinge, runes (staveless runes). The Younger Futhark developed further into themedieval runes(1100–1500), and theDalecarlian runes(c.1500–1800).

The exact development of the early runic alphabet remains unclear but the script ultimately stems from thePhoenician alphabet.Early runes may have developed from theRaetic,Venetic,Etruscan,orOld Latinas candidates. At the time, all of these scripts had the same angular letter shapes suited forepigraphy,which would become characteristic of the runes and related scripts in the region.

The process of transmission of the script is unknown. The oldest clear inscriptions are found in Denmark and northern Germany. A "West Germanic hypothesis" suggests transmission viaElbe Germanicgroups, while a "Gothichypothesis "presumes transmission via East Germanicexpansion.Runes continue to be used in a wide variety of ways in modern popular culture.

Name

[edit]Etymology

[edit]

The name stems from aProto-Germanicformreconstructedas*rūnō,which may be translated as 'secret, mystery; secret conversation; rune'. It is the source ofGothicrūna(𐍂𐌿𐌽𐌰,'secret, mystery, counsel'),Old Englishrún('whisper, mystery, secret, rune'),Old Saxonrūna('secret counsel, confidential talk'),Middle Dutchrūne('id'),Old High Germanrūna('secret, mystery'), andOld Norserún('secret, mystery, rune').[5][6]The earliest Germanic epigraphic attestation is thePrimitive Norserūnō(accusative singular), found on theEinang stone(AD 350–400) and theNoleby stone(AD 450).[4]

The term is related toProto-Celtic*rūna('secret, magic'), which is attested inOld Irishrún('mystery, secret'),Middle Welshrin('mystery, charm'),Middle Bretonrin('secret wisdom'), and possibly in the ancientGaulishCobrunus(<*com-rūnos'confident'; cf. Middle Welshcyfrin,Middle Bretonqueffrin,Middle Irishcomrún'shared secret, confidence') andSacruna(<*sacro-runa'sacred secret'), as well as inLeponticRunatis(< *runo-ātis'belonging to the secret'). However, it is difficult to tell whether they arecognates(linguistic siblings from a common origin), or if the Proto-Germanic form reflects an early borrowing from Celtic.[7][8]Various connections have been proposed with other Indo-European terms (for example:Sanskritráutiरौति'roar',Latinrūmor'noise, rumor';Ancient Greekeréōἐρέω'ask' andereunáōἐρευνάω'investigate'),[9]although linguistRanko Matasovićfinds them difficult to justify for semantic or linguistic reasons.[7]Because of this, some scholars have speculated that the Germanic and Celtic words may have been a shared religious term borrowed from an unknown non-Indo-European language.[4][7]

Related terms

[edit]In early Germanic, a rune could also be referred to as*rūna-stabaz,acompoundof*rūnōand*stabaz('staff; letter'). It is attested in Old Norserúna-stafr,Old Englishrún-stæf,and Old High Germanrūn-stab.[10]Other Germanic terms derived from*rūnōinclude*runōn('counsellor'),*rūnjanand*ga-rūnjan('secret, mystery'),*raunō('trial, inquiry, experiment'),*hugi-rūnō('secret of the mind, magical rune'), and*halja-rūnō('witch, sorceress'; literally '[possessor of the]Hel-secret').[11]It is also often part of personal names, including GothicRunilo(𐍂𐌿𐌽𐌹𐌻𐍉),FrankishRúnfrid,Old NorseAlfrún,Dagrún,Guðrún,Sigrún,Ǫlrún,Old EnglishÆlfrún,andLombardicGoderūna.[9]

TheFinnishwordruno,meaning 'poem', is an early borrowing from Proto-Germanic,[12]and the source of the term for rune,riimukirjain,meaning 'scratched letter'.[13]The root may also be found in theBaltic languages,whereLithuanianrunotimeans both 'to cut (with a knife)' and 'to speak'.[14]

The Old English formrúnsurvived into theearly modern periodasroun,which is now obsolete. The modern Englishruneis a later formation that is partly derived fromLate Latinruna,Old Norserún,andDanishrune.[6]

History and use

[edit]

The runes were in use among theGermanic peoplesfrom the 1st or 2nd century AD.[a]This period corresponds to the lateCommon Germanicstage linguistically, with a continuum of dialects not yet clearly separated into the three branches of later centuries:North Germanic,West Germanic,andEast Germanic.

No distinction is made in surviving runic inscriptions between long and short vowels, although such a distinction was certainly present phonologically in the spoken languages of the time. Similarly, there are no signs forlabiovelarsin the Elder Futhark (such signs were introduced in both theAnglo-Saxon futhorcand theGothic alphabetas variants ofp;seepeorð.)

Origins

[edit]The formation of the Elder Futhark was complete by the early 5th century, with theKylver Stonebeing the first evidence of thefutharkordering as well as of theprune.

Specifically, theRhaetic alphabetofBolzanois often advanced as a candidate for the origin of the runes, with only five Elder Futhark runes (ᛖe,ᛇï,ᛃj,ᛜŋ,ᛈp) having no counterpart in the Bolzano alphabet.[16]Scandinavian scholars tend to favor derivation from theLatin alphabetitself over Rhaetic candidates.[17][18][19]A "North Etruscan" thesis is supported by the inscription on theNegau helmetdating to the 2nd century BC.[20]This is in a northern Etruscan alphabet but features a Germanic name,Harigast.Giuliano and Larissa Bonfante suggest that runes derived from some North Italic alphabet, specificallyVenetic:But sinceRomansconqueredVenetoafter 200 BC, and then theLatin alphabetbecame prominent andVeneticculture diminished in importance,Germanicpeople could have adopted the Venetic alphabet within the 3rd century BC or even earlier.[21]

The angular shapes of the runes are shared with most contemporary alphabets of the period that were used for carving in wood or stone. There are nohorizontalstrokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the wood.[22]This characteristic is also shared by other alphabets, such as the early form of theLatin alphabetused for theDuenos inscription,but it is not universal, especially among early runic inscriptions, which frequently have variant rune shapes, including horizontal strokes. Runic manuscripts (that iswrittenrather than carved runes, such asCodex Runicus) also show horizontal strokes.

The "West Germanichypothesis "speculates on an introduction byWest Germanic tribes.This hypothesis is based on claiming that the earliest inscriptions of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, found in bogs and graves aroundJutland(theVimose inscriptions), exhibit word endings that, being interpreted byScandinavianscholars to beProto-Norse,are considered unresolved and long having been the subject of discussion.[b] In the early Runic period, differences between Germanic languages are generally presumed to be small. Another theory presumes aNorthwest Germanicunity preceding the emergence of Proto-Norse proper from roughly the 5th century.[c][d]An alternative suggestion explaining the impossibility of classifying the earliest inscriptions as either North or West Germanic is forwarded by È. A. Makaev, who presumes a "special runickoine",an early" literary Germanic "employed by the entire Late Common Germanic linguistic community after the separation of Gothic (2nd to 5th centuries), while the spoken dialects may already have been more diverse.[28]

The Meldorf fibula and Tacitus'sGermania

[edit]With the potential exception of theMeldorf fibula,a possible runic inscription found inSchleswig-Holsteindating to around 50 AD, the earliest reference to runes (and runic divination) may occur in Roman Senator Tacitus's ethnographicGermania.[29]Dating from around 98 CE, Tacitus describes the Germanic peoples as utilizing a divination practice involving rune-like inscriptions:

For divination and casting lots they have the highest possible regard. Their procedure for casting lots is uniform: They break off the branch of a fruit tree and slice into strips; they mark these by certain signs and throw them, as random chance will have it, on to a white cloth. Then a state priest, if the consultation is a public one, or the father of the family, if it is private, prays to the gods and, gazing to the heavens, picks up three separate strips and reads their meaning from the marks scored on them. If the lots forbid an enterprise, there can be no further consultation about it that day; if they allow it, further confirmation by divination is required.[30]

As Victoria Symons summarizes, "If the inscriptions made on the lots that Tacitus refers to are understood to be letters, rather than other kinds of notations or symbols, then they would necessarily have been runes, since no other writing system was available to Germanic tribes at this time."[29]

Early inscriptions

[edit]

Runic inscriptions from the 400-year period 150–550 AD are described as "Period I". These inscriptions are generally inElder Futhark,but the set of letter shapes andbindrunesemployed is far from standardized. Notably thej,s,andŋrunes undergo considerable modifications, while others, such aspandï,remain unattested altogether prior to the first full futhark row on theKylver Stone(c.400 AD).

Artifacts such as spear heads or shield mounts have been found that bear runic marking that may be dated to 200 AD, as evidenced by artifacts found across northern Europe inSchleswig(North Germany),Funen,Zealand,Jutland(Denmark), andScania(Sweden). Earlier—but less reliable—artifacts have been found inMeldorf,Süderdithmarschen,in northern Germany; these include brooches and combs found in graves, most notably theMeldorf fibula,and are supposed to have the earliest markings resembling runic inscriptions.

Magical or divinatory use

[edit]

The stanza 157 ofHávamálattribute to runes the power to bring that which is dead back to life. In this stanza,Odinrecounts a spell:

Þat kann ek it tolfta, |

I know a twelfth one |

The earliest runic inscriptions found on artifacts give the name of either the craftsman or the proprietor, or sometimes, remain a linguistic mystery. Due to this, it is possible that the early runes were not used so much as a simple writing system, but rather asmagicalsigns to be used for charms. Although some say the runes were used fordivination,there is no direct evidence to suggest they were ever used in this way. The nameruneitself, taken to mean "secret, something hidden", seems to indicate that knowledge of the runes was originally considered esoteric, or restricted to an elite.[citation needed]The 6th-centuryBjörketorp Runestonewarns inProto-Norseusing the wordrunein both senses:

Haidzruno runu, falahak haidera, ginnarunaz. Arageu haeramalausz uti az. Weladaude, sa'z þat barutz. Uþarba spa.

I, master of the runes(?) conceal here runes of power. Incessantly (plagued by) maleficence, (doomed to) insidious death (is) he who breaks this (monument). I prophesy destruction / prophecy of destruction.[33]

The same curse and use of the word, rune, is also found on theStentoften Runestone.There also are some inscriptions suggesting a medieval belief in the magical significance of runes, such as theFranks Casket(AD 700) panel.

Charm words, such asauja,laþu,laukaʀ,and most commonly,alu,[34]appear on a number ofMigration periodElder Futhark inscriptions as well as variants and abbreviations of them. Much speculation and study has been produced on the potential meaning of these inscriptions. Rhyming groups appear on some early bracteates that also may be magical in purpose, such assalusaluandluwatuwa.Further, an inscription on theGummarp Runestone(500–700 AD) gives a cryptic inscription describing the use of three runic letters followed by the Elder Futhark f-rune written three times in succession.[35]

Nevertheless, it has proven difficult to find unambiguous traces of runic "oracles": althoughNorseliterature is full of references to runes, it nowhere contains specific instructions on divination. There are at least three sources on divination with rather vague descriptions that may, or may not, refer to runes:Tacitus's 1st-centuryGermania,Snorri Sturluson's 13th-centuryYnglinga saga,andRimbert's 9th-centuryVita Ansgari.

The first source, Tacitus'sGermania,[36]describes "signs" chosen in groups of three and cut from "a nut-bearing tree", although the runes do not seem to have been in use at the time of Tacitus' writings. A second source is theYnglinga saga,whereGranmar,the king ofSödermanland,goes toUppsalafor theblót.There, the "chips" fell in a way that said that he would not live long (Féll honum þá svo spánn sem hann mundi eigi lengi lifa). These "chips", however, are easily explainable as ablótspánn(sacrificial chip), which was "marked, possibly with sacrificial blood, shaken, and thrown down like dice, and their positive or negative significance then decided."[37][page needed]

The third source is Rimbert'sVita Ansgari,where there are three accounts of what some believe to be the use of runes for divination, but Rimbert calls it "drawing lots". One of these accounts is the description of how a renegade Swedish king,Anund Uppsale,first brings a Danish fleet toBirka,but then changes his mind and asks the Danes to "draw lots". According to the story, this "drawing of lots" was quite informative, telling them that attackingBirkawould bring bad luck and that they should attack a Slavic town instead. The tool in the "drawing of lots", however, is easily explainable as ahlautlein(lot-twig), which according to Foote and Wilson[38]would be used in the same manner as ablótspánn.

The lack of extensive knowledge on historical use of the runes has not stopped modern authors from extrapolating entire systems of divination from what few specifics exist, usually loosely based on the reconstructed names of the runes and additional outside influence.

A recent study of runic magic suggests that runes were used to create magical objects such as amulets,[39][page needed]but not in a way that would indicate that runic writing was any more inherently magical, than were other writing systems such as Latin or Greek.

Medieval use

[edit]

AsProto-Germanicevolved into its later language groups, the words assigned to the runes and the sounds represented by the runes themselves began to diverge somewhat and each culture would create new runes, rename or rearrange its rune names slightly, or stop using obsolete runes completely, to accommodate these changes. Thus, the Anglo-Saxon futhorc has several runes peculiar to itself to representdiphthongsunique to (or at least prevalent in) Old English.

Some later runic finds are on monuments (runestones), which often contain solemn inscriptions about people who died or performed great deeds. For a long time it was presumed that this kind of grand inscription was the primary use of runes, and that their use was associated with a certain societal class of rune carvers.

In the mid-1950s, however, approximately 670 inscriptions, known as theBryggen inscriptions,were found inBergen.[40]These inscriptions were made on wood and bone, often in the shape of sticks of various sizes, and contained information of an everyday nature—ranging from name tags, prayers (often inLatin), personal messages, business letters, and expressions of affection, to bawdy phrases of a profane and sometimes even of a vulgar nature. Following this find, it is nowadays commonly presumed that, at least in late use, Runic was a widespread and common writing system.

In the later Middle Ages, runes also were used in theclog almanacs(sometimes calledRunic staff,Prim,orScandinavian calendar) of Sweden andEstonia.The authenticity of some monuments bearing Runic inscriptions found in Northern America is disputed; most of them have been dated to modern times.

Runes in Eddic poetry

[edit]InNorse mythology,the runic alphabet is attested to a divine origin (Old Norse:reginkunnr). This is attested as early as on theNoleby Runestonefromc. 600 ADthat readsRuno fahi raginakundo toj[e'k]a...,meaning "I prepare the suitable divine rune..."[41]and in an attestation from the 9th century on theSparlösa Runestone,which readsOk rað runaʀ þaʀ rægi[n]kundu,meaning "And interpret the runes of divine origin".[42]In thePoetic EddapoemHávamál,Stanza 80, the runes also are described asreginkunnr:

Þat er þá reynt, |

That is now proved, |

The poemHávamálexplains that the originator of the runes was the major deity,Odin.Stanza 138 describes how Odin received the runes through self-sacrifice:

Veit ek at ek hekk vindga meiði a |

In stanza 139, Odin continues:

Við hleifi mik seldo ne viþ hornigi, |

No bread did they give me nor adrink from a horn, |

In the Poetic Edda poemRígsþulaanother origin is related of how the runic alphabet became known to humans. The poem relates howRíg,identified asHeimdallin the introduction, sired three sons—Thrall(slave),Churl(freeman), andJarl(noble)—by human women. These sons became the ancestors of the three classes of humans indicated by their names. When Jarl reached an age when he began to handle weapons and show other signs of nobility,Rígreturned and, having claimed him as a son, taught him the runes. In 1555, the exiled Swedish archbishopOlaus Magnusrecorded a tradition that a man namedKettil Runskehad stolen three rune staffs from Odin and learned the runes and their magic.

Runic alphabets

[edit]Elder Futhark (2nd to 8th centuries)

[edit]

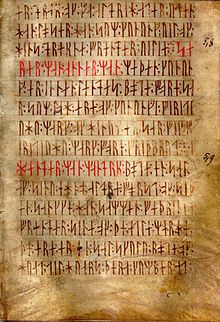

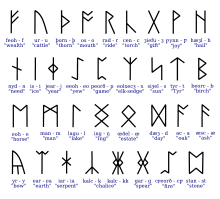

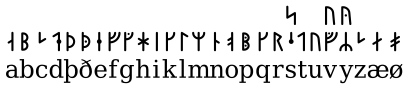

The Elder Futhark, used for writingProto-Norse,consists of 24 runes that often are arranged in three groups of eight; each group is referred to as anætt(Old Norse, meaning 'clan, group'). The earliest known sequential listing of the full set of 24 runes dates to approximately AD 400 and is found on theKylver StoneinGotland,Sweden.

Most probably each rune had a name, chosen to represent the sound of the rune itself. The names are, however, not directly attested for the Elder Futhark themselves.Germanic philologistsreconstructnames inProto-Germanicbased on the names given for the runes in the later alphabets attested in therune poemsand the linked names of the letters of theGothic alphabet.For example, the letter /a/ was named from the runicletter![]() calledAnsuz.An asterisk before the rune names means that they areunattestedreconstructions.The 24 Elder Futhark runes are the following:[45]

calledAnsuz.An asterisk before the rune names means that they areunattestedreconstructions.The 24 Elder Futhark runes are the following:[45]

| Rune | UCS | Trans. | IPA | Proto-Germanicname | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᚠ | f | /ɸ/,/f/ | *fehu | "chattel, wealth" | |

| ᚢ | u | /u(ː)/ | ?*ūruz | "aurochs",Wild ox (or *ûram" water/slag "?) | |

| ᚦ | þ | /θ/,/ð/ | ?*þurisaz | "Thurs" (seeJötunn) or *þunraz ( "the godThunraz") | |

| ᚨ | a | /a(ː)/ | *ansuz | "god" | |

| ᚱ | r | /r/ | *raidō | "ride, journey" | |

| ᚲ | k (c) | /k/ | ?*kaunan | "ulcer"? (or *kenaz "torch"?) | |

| ᚷ | g | /ɡ/ | *gebō | "gift" | |

| ᚹ | w | /w/ | *wunjō | "joy" | |

| ᚺ ᚻ | h | /h/ | *hagalaz | "hail"(the precipitation) | |

| ᚾ | n | /n/ | *naudiz | "need" | |

| ᛁ | i | /i(ː)/ | *īsaz | "ice" | |

| ᛃ | j | /j/ | *jēra- | "year, good year, harvest" | |

| ᛇ | ï (æ) | /æː/[46] | *ī(h)waz | "yew-tree" | |

| ᛈ | p | /p/ | ?*perþ- | meaning unknown; possibly "pear-tree". | |

| ᛉ | z | /z/ | ?*algiz | "elk" (or "protection, defence"[47]) | |

| ᛊ ᛋ | s | /s/ | *sōwilō | "sun" | |

| ᛏ | t | /t/ | *tīwaz | "the godTiwaz" | |

| ᛒ | b | /b/ | *berkanan | "birch" | |

| ᛖ | e | /e(ː)/ | *ehwaz | "horse" | |

| ᛗ | m | /m/ | *mannaz | "man" | |

| ᛚ | l | /l/ | *laguz | "water, lake" (or possibly *laukaz "leek" ) | |

| ᛜ | ŋ | /ŋ/ | *ingwaz | "the godIngwaz" | |

| ᛞ | d | /d/ | *dagaz | "day" | |

| ᛟ | o | /o(ː)/ | *ōþila-/*ōþala- | "heritage, estate, possession" |

Anglo-Saxon runes (5th to 11th centuries)

[edit]

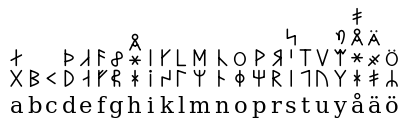

The Anglo-Saxon runes, also known as thefuthorc(sometimes writtenfuþorc), are an extended alphabet, consisting of 29, and later 33, characters. It was probably used from the 5th century onwards. There are competing theories as to the origins of the Anglo-Saxon (also called Anglo-Frisian) Futhorc. One theory proposes that it was developed inFrisiaand later spread toEngland,[citation needed]while another holds that Scandinavians introduced runes to England, where the futhorc was modified and exported to Frisia.[citation needed]Some examples of futhorc inscriptions are found on theThames scramasax,in theVienna Codex,inCotton OthoB.x (Anglo-Saxon rune poem) and on theRuthwell Cross.

The Anglo-Saxon rune poem gives the following characters and names:ᚠfeoh,ᚢur,ᚦþorn,ᚩos,ᚱrad,ᚳcen,ᚷgyfu,ᚹƿynn,ᚻhægl,ᚾnyd,ᛁis,ᛄger,ᛇeoh,ᛈpeorð,ᛉeolh,ᛋsigel,ᛏtir,ᛒbeorc,ᛖeh,ᛗmann,ᛚlagu,ᛝing,ᛟœthel,ᛞdæg,ᚪac,ᚫæsc,ᚣyr,ᛡior,ᛠear.

Extra runes attested to outside of the rune poem includeᛢcweorð,ᛣcalc,ᚸgar, andᛥstan. Some of these additional letters have only been found inmanuscripts.Feoh, þorn, and sigel stood for [f], [θ], and [s] in most environments, but voiced to [v], [ð], and [z] between vowels or voiced consonants. Gyfu and wynn stood for the lettersyoghandwynn,which became [g] and [w] inMiddle English.

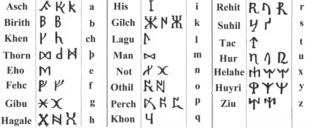

"Marcomannic runes" (8th to 9th centuries)

[edit]

A runic alphabet consisting of a mixture of Elder Futhark with Anglo-Saxon futhorc is recorded in a treatise calledDe Inventione Litterarum,ascribed toHrabanus Maurusand preserved in 8th- and 9th-century manuscripts mainly from the southern part of theCarolingian Empire(Alemannia,Bavaria). The manuscript text attributes the runes to theMarcomanni, quos nos Nordmannos vocamus,and hence traditionally, the alphabet is called "Marcomannic runes", but it has no connection with theMarcomanni,and rather is an attempt of Carolingian scholars to represent all letters of the Latin alphabets with runic equivalents.

Wilhelm Grimmdiscussed these runes in 1821.[48]

Younger Futhark (9th to 11th centuries)

[edit]

The Younger Futhark, also called Scandinavian Futhark, is a reduced form of theElder Futhark,consisting of only 16 characters. The reduction correlates with phonetic changes whenProto-Norseevolved intoOld Norse.They are found in Scandinavia andViking Agesettlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. They are divided into long-branch (Danish) and short-twig (Swedish and Norwegian) runes. The difference between the two versions is a matter of controversy. A general opinion is that the difference between them was functional (viz., the long-branch runes were used for documentation on stone, whereas the short-twig runes were in everyday use for private or official messages on wood).

Medieval runes (12th to 15th centuries)

[edit]

In the Middle Ages, the Younger Futhark in Scandinavia was expanded, so that it once more contained one sign for each phoneme of theOld Norse language.Dotted variants ofvoicelesssigns were introduced to denote the correspondingvoicedconsonants, or vice versa, voiceless variants of voiced consonants, and several new runes also appeared for vowel sounds. Inscriptions in medieval Scandinavian runes show a large number of variant rune forms, and some letters, such ass,c,andzoften were used interchangeably.[49][50]

Medieval runes were in use until the 15th century. Of the total number of Norwegian runic inscriptions preserved today, most are medieval runes. Notably, more than 600 inscriptions using these runes have been discovered inBergensince the 1950s, mostly on wooden sticks (the so-calledBryggen inscriptions). This indicates that runes were in common use side by side with the Latin alphabet for several centuries. Indeed, some of the medieval runic inscriptions are written in Latin.

Dalecarlian runes (16th to 19th centuries)

[edit]

According to Carl-Gustav Werner, "In the isolated province ofDalarnain Sweden a mix of runes and Latin letters developed. "[51]The Dalecarlian runes came into use in the early 16th century and remained in some use up to the 20th century.[52]Some discussion remains on whether their use was an unbroken tradition throughout this period or whether people in the 19th and 20th centuries learned runes from books written on the subject. The character inventory was used mainly for transcribingSwedishin areas whereElfdalianwas predominant.

Differences from Roman script

[edit]While Roman script would ultimately replace runes in most contexts, it differed significantly from runic script. For example, on the differences between the use of Anglo-Saxon runes and the Latin script that would come to replace them, runologist Victoria Symons says:

As well as being distinguished from the roman alphabet in visual appearance and letter order, the fuþorc is further set apart by the fact that, unlike their roman counterparts, runic letters are often associated not only with sound values but also with names. These names are often nouns and, in almost all instances, they begin with the sound value represented by the associated letter.... The fact that each rune represents [both] a sound value and a word gives this writing system a multivalent quality that further distinguishes it from roman script. A roman letter simply represents its sound value. When used, for example, for the purpose of pagination, such letters can assume added significance, but this is localised to the context of an individual manuscript. Runic letters, on the other hand, are inherently multivalent; they can, and often do, represent several different kinds of information simultaneously. This aspect of runic letters is one that is frequently employed and exploited by writers and scribes who include them in their manuscripts.[53]

Use as ideographs (Begriffsrunen)

[edit]In addition to their historic use as letters in the runic alphabets, runes were also used to represent their names (ideographs). Such instances are sometimes referred to by way of the modern German loan wordBegriffsrunen,meaning 'concept-runes' (singularBegriffsrune). The criteria for the use ofBegriffsrunenand the frequency of their use by ancient rune-writers remains controversial.[54]The topic ofBegriffsrunenhas produced much discussion among runologists. RunologistKlaus Düwelhas proposed two criteria for the identification of runes asBegriffsrunen:A graphic argument and a semantic argument.[54]

Examples ofBegriffsrunen(or potentialBegriffsrunen) include the following:

| Inscription | Date | Script | Language | Rune | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lindholm amulet | 2nd to 4th centuries | Elder Futhark | Proto-Norse | Several different runes | In this inscription, several runes repeat in a sentence to form an unknown meaning. Various scholars have proposed that these runes represent repeatedBegriffsrunen. |

| Ring of Pietroassa | 250–400 AD | Elder Futhark | Gothic | Odal (rune) | This object was cut by thieves, damaging one of the runes. The identity of this rune was debated by scholars until a photograph of it was republished that, according to runologist Bernard Mees, clearly indicates it to have beenOdal (rune).[55] |

| Stentoften Runestone | 500–700 AD | Elder Futhark | Proto-Norse | Jēran | This inscription is commonly cited as containing aBegriffsrune.[54] |

In addition to the instances above, several different runes occur as ideographs in Old English and Old Norse manuscripts (featuringAnglo-Saxon runesandYounger Futharkrunes respectively). Runologist Thomas Birkett summarizes these numerous instances as follows:

Themaðrrune is found regularly in Icelandic manuscripts, theférune somewhat less frequently, whilst in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts the runesmon,dæg,wynnandeþelare all used on occasion. These are some of the most functional of the rune names, occurring relatively often in written language, unlike the elusivepeorð,for example, which would be of little or no use as an abbreviation because of its rarity. The practicality of using an abbreviation for a familiar noun such as 'man' is demonstrated clearly in the Old Norse poemHávamál,where themaðrrune is used a total of forty-five times, saving a significant amount of space and effort (Codex Regius:5–14)[56]

Academic study

[edit]The modern study of runes was initiated during the Renaissance, byJohannes Bureus(1568–1652). Bureus viewed runes as holy or magical in akabbalisticsense. The study of runes was continued byOlof Rudbeck Sr(1630–1702) and presented in his collectionAtlantica.Anders Celsius(1701–1744) further extended the science of runes and travelled around the whole of Sweden to examine therunstenar.From the "golden age ofphilology"in the 19th century, runology formed a specialized branch ofGermanic linguistics.

Body of inscriptions

[edit]

The largest group of surviving Runic inscription areViking AgeYounger Futharkrunestones, commonly found in Denmark and Sweden.[58]Another large group are medieval runes, most commonly found on small objects, often wooden sticks. The largest concentration of runic inscriptions are theBryggen inscriptionsfound inBergen,more than 650 in total.Elder Futharkinscriptions number around 350, about 260 of which are from Scandinavia, of which about half are onbracteates.Anglo-Saxon futhorcinscriptions number around 100 items.

Modern use

[edit]Runic alphabets have seen numerous uses since the 18th-centuryViking revival,in ScandinavianRomantic nationalism(Gothicismus) andGermanic occultismin the 19th century, and in the context of theFantasygenre and ofmodern Germanic paganismin the 20th century.[citation needed]

Esotericism

[edit]Germanic mysticism and Nazi Germany

[edit]

The pioneer of theArmanistbranch ofAriosophyand one of the more important figures inesotericism in Germany and Austriain the late 19th and early 20th century was theAustrianoccultist, mysticist, andvölkischauthor,Guido von List.In 1908, he published inDas Geheimnis der Runen( "The Secret of the Runes" ) a set of eighteen so-called, "Armanen runes",based on the Younger Futhark and runes of List's own introduction, which allegedly were revealed to him in a state of temporary blindness after cataract operations on both eyes in 1902. The use of runes inGermanic mysticism,notably List's "Armanen runes" and the derived "Wiligut runes"byKarl Maria Wiligut,played a certain role inNazi symbolism.The fascination with runic symbolism was mostly limited toHeinrich Himmler,and not shared by the other members of the Nazi top echelon. Consequently, runes appear mostly in insignia associated with theSchutzstaffel( "SS" ), the paramilitary organization led by Himmler. Wiligut is credited with designing theSS-Ehrenring,which displays a number of "Wiligut runes".[citation needed]

Modern paganism and esotericism

[edit]Runes are popular inNew Ageesotericism,modern Germanic paganism,and to a lesser extent in other forms ofmodern paganism.Various systems ofRunic divinationhave been published since the 1980s, notably byRalph Blum(1982),Stephen Flowers(1984, onward),Stephan Grundy(1990), and Nigel Pennick (1995).[citation needed]

TheUthark theoryoriginally was proposed as a scholarly hypothesis bySigurd Agrellin 1932. In 2002, Swedish esotericistThomas Karlssonpopularized this "Uthark" runic row, which he refers to as, the "night side of the runes", in the context of modern occultism.[citation needed]

Bluetooth

[edit]

TheBluetoothlogo is the combination of two runes of theYounger Futhark,ᚼhagallandᛒbjarkan,equivalent to the letters H and B, that are the initials ofHarald “Blåtand” Gormsson's name (Bluetoothin English), who was a king of Denmark from theViking Age.[citation needed]

Fantasy Literature

[edit]Runes play an important role in the horror story "Casting the Runes," by the academic Medievalist and ghost story author M. R. James, first published in his 1911 collection "More Ghost Stories of an Antiquary." InJ. R. R. Tolkien's novelThe Hobbit(1937), the Anglo-Saxon runes are used on a map and on the title page to emphasize its connection to theDwarves.They also were used in the initial drafts ofThe Lord of the Rings,but later were replaced by theCirthrune-like alphabet invented by Tolkien, used to write the language of the Dwarves,Khuzdul.Following Tolkien, historical and fictional runes appear commonly in modern popular culture, particularly infantasy literature,like inJ. K. Rowling'sHarry Potter,where Runes is a subject taught at Hogwarts, also in the 7th bookHarry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,Dumbledore gave Hermione a children's book calledThe Tales of Beedle the Bardwhich is written in runes.[citation needed]

Video, board and role-playing games

[edit]Runes feature extensively in many video games that incorporate themes from early Germanic cultures, includingHellblade: Senua's Sacrifice,Jøtun,NorthgardandGod of War.They are used for a range of purposes including as names, symbols, decoration and on runestones that provide information about Nordic mythology and background for the game's narrative.[59][60][61]

The 1992 video gameHeimdallused runes as "magical symbols" associated with unnatural forces.Role-playing games,such as theUltimaseries,use a runic font for in-game signs and printed maps and booklets, andMetagaming'sThe Fantasy Tripused rune-based cipher for clues and jokes throughout its publications.[citation needed]

Unicode

[edit]

Runic alphabets were added to theUnicodeStandard in September, 1999 with the release of version 3.0.

TheUnicode blockfor Runic alphabets is U+16A0–U+16FF. It is intended to encode the letters of theElder Futhark,theAnglo-Frisian runes,and theYounger Futharklong-branch and short-twig (but not the staveless) variants, in cases where cognate letters have the same shape resorting to "unification".

The block as of Unicode 3.0 contained 81 symbols: 75 runic letters (U+16A0–U+16EA), 3 punctuation marks (Runic Single Punctuation U+16EB᛫,Runic Multiple Punctuation U+16EC᛬and Runic Cross Punctuation U+16ED᛭), and three runic symbols that are used in early modernrunic calendarstaves ( "Golden number Runes", RunicArlaugSymbol U+16EEᛮ,RunicTvimadurSymbol U+16EFᛯ,RunicBelgthorSymbol U+16F0ᛰ). As of Unicode 7.0 (2014), eight characters were added, three attributed toJ. R. R. Tolkien's mode of writing Modern English in Anglo-Saxon runes, and five for the "cryptogrammic" vowel symbols used in an inscription on theFranks Casket.

| Runic[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart(PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+16Ax | ᚠ | ᚡ | ᚢ | ᚣ | ᚤ | ᚥ | ᚦ | ᚧ | ᚨ | ᚩ | ᚪ | ᚫ | ᚬ | ᚭ | ᚮ | ᚯ |

| U+16Bx | ᚰ | ᚱ | ᚲ | ᚳ | ᚴ | ᚵ | ᚶ | ᚷ | ᚸ | ᚹ | ᚺ | ᚻ | ᚼ | ᚽ | ᚾ | ᚿ |

| U+16Cx | ᛀ | ᛁ | ᛂ | ᛃ | ᛄ | ᛅ | ᛆ | ᛇ | ᛈ | ᛉ | ᛊ | ᛋ | ᛌ | ᛍ | ᛎ | ᛏ |

| U+16Dx | ᛐ | ᛑ | ᛒ | ᛓ | ᛔ | ᛕ | ᛖ | ᛗ | ᛘ | ᛙ | ᛚ | ᛛ | ᛜ | ᛝ | ᛞ | ᛟ |

| U+16Ex | ᛠ | ᛡ | ᛢ | ᛣ | ᛤ | ᛥ | ᛦ | ᛧ | ᛨ | ᛩ | ᛪ | ᛫ | ᛬ | ᛭ | ᛮ | ᛯ |

| U+16Fx | ᛰ | ᛱ | ᛲ | ᛳ | ᛴ | ᛵ | ᛶ | ᛷ | ᛸ | |||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- Bautil

- Gothic runic inscriptions

- Etruscan alphabet

- List of runestones

- Pentadic numerals– Runic notation for presenting numbers

- Ogham

- Runiform (disambiguation),various scripts having a "rune-like" appearance

- Runic magic

- Sveriges runinskrifter

- Letter symbolism

Footnotes

[edit]- ^The oldest known runic inscription dates to around AD 150 and is found on a comb discovered in the bog ofVimose,Funen,Denmark.[15]The inscription readsharja;a disputed candidate for a 1st-century inscription is on theMeldorf fibulain southernJutland.

- ^Inscriptions such aswagnija,niþijo,andharijaare supposed to represent tribe names, tentatively proposed to beVangiones,theNidensis,and theHariitribes located in theRhineland.[23]Since names ending in-ioreflect Germanic morphology representing the Latin ending-ius,and the suffix-iniuswas reflected by Germanic-inio-,[24][25]the question of the problematic ending-ijoin masculine Proto-Norse would be resolved by assuming Roman (Rhineland) influences, while "the awkward ending -a oflaguþewa[26]may be solved by accepting the fact that the name may indeed be West Germanic ".[23]

- ^Penzl & Hall 1994aassume a period of "Proto-Nordic-Westgermanic" unity down to the 5th century and theGallehus hornsinscription.[27]

- ^The division between Northwest Germanic and Proto-Norse is somewhat arbitrary.[28]

References

[edit]- ^Himelfarb, Elizabeth J."First Alphabet Found in Egypt",Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (January/February 2000): 21.

- ^Runic(PDF)(chart), Unicode,archived(PDF)from the original on 2021-10-07,retrieved2018-03-24.

- ^Spurkland, Terje (2005).Norwegian runes and runic inscriptions.Woodbridge: The Boydell press. pp. 42–43.ISBN1-84383-186-4.

- ^abcKoch 2020,p. 137.

- ^de Vries 1962,pp. 453–454;Orel 2003,p. 310;Koch 2020,p. 137

- ^abOxford English Dictionary Online,s.v. †roun,n. andrune,n.2.

- ^abcMatasović, Ranko(2009).Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic.Brill. p. 316.ISBN9789004173361.

- ^Delamarre, Xavier(2003).Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental.Errance. p. 122.ISBN9782877723695.

- ^abde Vries 1962,pp. 453–454.

- ^Orel 2003,p. 310.

- ^Orel 2003,pp. 155, 190, 310.

- ^Häkkinen, Kaisa. Nykysuomen etymologinen sanakirja

- ^Nykysuomen sanakirja: "riimu"

- ^"Dictionary of the Lithuanian Language".LKZ. Archived fromthe originalon 2017-08-11.Retrieved2010-04-13.

- ^Stoklund 2003,p. 173.

- ^Mees 2000.

- ^Odenstedt 1990.

- ^Williams 1996.

- ^Dictionary of the Middle Ages(under preparation). Oxford University Press. Archived fromthe originalon 2007-06-23.

- ^Markey 2001.

- ^Bonfante, Giuliano; Bonfante, Larissa (2002).The Etruscan Language.Manchester University Press. p. 119.ISBN9780719055409.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-06-22.Retrieved2015-06-22.

- ^Rix, Robert W. (2011). "Runes and Roman: Germanic literacy and the significance of runic writing".Textual Cultures.6:114–144.doi:10.2979/textcult.6.1.114.

- ^abLooijenga 1997.

- ^Weisgerber 1968,pp. 135, 392ff.

- ^Weisgerber 1966–1967,p. 207.

- ^Syrett 1994,pp. 44ff.

- ^Penzl & Hall 1994b,p. 186.

- ^abAntonsen 1965,p. 36.

- ^abSymons 2020: 5.

- ^Mattingly 2009: 39.

- ^ab"Hávamál",Norrøne Tekster og Kvad,Norway, archived fromthe originalon 2007-05-08.

- ^Larrington 1999,p. 37.

- ^"DR 360",Rundata(entry) (2.0 for Windows ed.).

- ^MacLeod & Mees 2006,pp. 100–01.

- ^Page 2005,p. 31.

- ^Tacitus, Cornelius(1942)."Germany and its Tribes, chapter 10".In Alfred John Church; William Jackson Brodribb; Lisa Cerrato (eds.).Complete Works of Tacitus(1999 Perseus ed.). New York: Random House.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-08-03.Retrieved2023-01-18.

- ^Foote & Wilson 1970.

- ^Foote & Wilson 1970,p. 401.

- ^MacLeod & Mees 2006.

- ^William, Gareth (2007).West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300.Brill Publishers.p. 473.ISBN9789047421214.Retrieved2018-05-22.

- ^"Vg 63",Rundata(entry) (2.0 for Windows ed.).

- ^"Vg 119",Rundata(entry) (2.0 for Windows ed.).

- ^Larrington 1999,p. 25.

- ^abLarrington 1999,p. 34.

- ^Page 2005,pp. 8, 15–16.

- ^also rendered/ɛː/,seeProto-Germanic phonology.

- ^Ralph Warren, Victor Elliott, Runes: an introduction, Manchester University Press ND, 1980, 51-53.

- ^Grimm, William(1821), "18",Ueber deutsche Runen[Concerning German runes] (in German), pp. 149–59.

- ^Jacobsen & Moltke 1942,p. vii.

- ^Werner 2004,p. 20.

- ^Werner 2004,p. 7.

- ^Brix, Lise (May 21, 2015)."Isolated people in Sweden only stopped using runes 100 years ago".ScienceNordic.Archivedfrom the original on July 19, 2019.RetrievedJuly 22,2015.

- ^Symons 2016,p. 6-7.

- ^abcSee discussion in for exampleDüwel 2004:123–124 andLooijenga 2003:17.

- ^MacLeod & Mees 2006: 173.

- ^Birkett 2010: 1.

- ^Looijenga 2003: 160.

- ^de Gruyter, Walter (2002).The Nordic Languages, Volume 1.Walter de Gruyter. p. 700.ISBN9783110197051.Retrieved2018-05-22.

- ^Lysiane 2018,pp. 16, 20, 35–36.

- ^Northgard.

- ^Hakala 2020,p. 21.

Sources

[edit]- "Northgard – Balancing Patch 7 – July 2021 – Steam News".store.steampowered.com.20 July 2021.Retrieved14 May2022.

- Antonsen, Elmer H. (1965). "On Defining Stages in Prehistoric Germanic".Language.41(1): 19–36.doi:10.2307/411849.JSTOR411849.

- Birkett, Thomas. 2010. "Thealysendlecanrune: Runic abbreviations in their immediate literary contextArchived2021-08-29 at theWayback Machine".Preprints to The 7th International Symposium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions, Oslo 2010Archived2021-08-29 at theWayback Machine.Last accessed 29 August 2021.University of Oslo.

- de Vries, Jan(1962).Altnordisches Etymologisches Worterbuch(1977 ed.). Brill.ISBN978-90-04-05436-3.

- Düwel, Klaus (2001).Runenkunde(in German). JB Metzler.

- Düwel, Klaus (2004). "Runic". In Read, Malcolm; Murdoch, Brian (eds.).Early Germanic Literature and Culture.Boydell & Brewer. pp. 121–147.ISBN9781571131997.

- Foote, P. G.; Wilson, D. M. (1970).The Viking Achievement.London: Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 401.ISBN978-0-283-97926-2.

- Jacobsen, Lis;Moltke, Erik(1942).Danmarks Runeindskrifter.Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaards.

- Koch, John T.(2020).Celto-Germanic, Later Prehistory and Post-Proto-Indo-European vocabulary in the North and West(PDF).Aberystwyth Canolfan Uwchefrydiau Cymreig a Cheltaidd Prifysgol Cymru, University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies.ISBN9781907029325.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2021-11-25.Retrieved2021-12-07.

- Larrington, Carolyne (1999).The Poetic Edda.Oxford World's Classics.Translated by Larrington.ISBN978-0-19-283946-6.

- Looijenga, Tineke (2003).Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions.Leiden: Brill.ISBN978-90-04-12396-0.

- Looijenga, JH (1997).Runes Around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150–700(Thesis). Groningen University.Archivedfrom the original on 2006-07-28.Retrieved2006-02-06.

- Lysiane, Lasausse (2018)."Norse mythology in video games: part of immanent Nordic regional branding".University of Helsinki.

- MacLeod, Mindy; Mees, Bernard (2006).Runic Amulets and Magic Objects.Woodbridge, UK; Rochester, NY:Boydell Press.ISBN978-1-84383-205-8.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-09-19.Retrieved2020-09-12.

- Markey, TL (2001). "A Tale of the Two Helmets: Negau A and B".Journal of Indo-European Studies.29:69–172.

- Mees, Bernard (2000). "The North Etruscan Thesis of the Origin of the Runes".Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi.115:33–82.

- Odenstedt, Bengt (1990).On the Origin and Early History of the Runic Script.Uppsala, Sweden: Gustav Adolfs akademien.ISBN978-91-85352-20-3.

- Orel, Vladimir E.(2003).A Handbook of Germanic Etymology.Brill.ISBN978-90-04-12875-0.

- Page, Raymond Ian(2005).Runes.The British Museum Press. p. 31.ISBN978-0-7141-8065-6.

- Hakala, Pyry (2020)."Modern Trends in God of War".Tampere University.

- Penzl, Herbert; Hall, Margaret Austin (Mar 1994a). "The Cambridge history of the English language, vol. I: the beginnings to 1066".Language(review).70(1): 185–89.doi:10.2307/416753.eISSN1535-0665.ISSN0097-8507.JSTOR416753.

- Penzl, Herbert; Hall, Margaret Austin (1994b).Englisch: Eine Sprachgeschichte nach Texten von 350 bis 1992: vom Nordisch-Westgermanischen zum Neuenglischen.Germanistische Lehrbuchsammlung: Literatur. Vol. 82. Lang.ISBN978-3-906751-79-5.

- Stoklund, M. (2003). "The first runes – the literary language of the Germani".The Spoils of Victory – the North in the Shadow of the Roman Empire.Nationalmuseet.

- Symons, Victoria (2016).Runes and Roman Letters in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts.De Gruyter.

- Syrett, Martin (1994).The Unaccented Vowels of Proto-Norse.North-Western European Language Evolution. Vol. 11. John Benjamins.ISBN978-87-7838-049-4.

- Weisgerber, Johannes Leo (1966–1967). "Frühgeschichtliche Sprachbewegungen im Kölner Raum (mit 8 Karten)".Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter(in German).

- Weisgerber, Johannes Leo (1968).Die Namen der Ubier(in German). Cologne: Opladen.

- Werner, Carl-Gustav (2004).The Allrunes Font and Package(PDF).The Comprehensive Tex Archive Network.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2017-10-20.Retrieved2006-06-21.

- Williams, Henrik (1996). "The Origin of the Runes".Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik.45:211–18.doi:10.1163/18756719-045-01-90000019.

External links

[edit]- Nytt om Runer(runology journal),NO:UIO

- Bibliography of Runic Scholarship,Galinn grund, archived from the original on 2008-09-05

{{citation}}:CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Gamla Runinskrifter,SE:Christer hamp

- Gosse, Edmund William(1911)..Encyclopædia Britannica.Vol. 23 (11th ed.). pp. 852–853.

- Smith, Nicole; Beale, Gareth; Richards, Julian; Scholma-Mason, Nela (2018),"Maeshowe: The Application of RTI to Norse Runes (Data Paper)",Internet Archaeology(47),doi:10.11141/ia.47.8,S2CID165773006

- Old Norse Onlineby Todd B. Krause and Jonathan Slocum, free online lessons at theLinguistics Research Centerat theUniversity of Texas at Austin,contains alesson on runic inscriptions

- Scratching runes was not much different from spraying tags,Frisia Coast Trail (2023)