Russia–United Kingdom relations

| |

United Kingdom |

Russia |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| British Embassy, Moscow | Embassy of Russia, London |

| Envoy | |

| AmbassadorNigel Casey | AmbassadorAndrey Kelin |

Russia–United Kingdom relations,alsoAnglo-Russian relations,[1]are the bilateral relations betweenRussiaand theUnited Kingdom.Formal ties between the nations started in 1553. Russia and Britain became allies againstNapoleonin the early-19th century. They were enemies in theCrimean Warof the 1850s, and rivals in theGreat Gamefor control of central Asia in the latter half of the 19th century. They allied again in World WarsIandII,although theRussian Revolutionof 1917 strained relations. The two countries again became enemies during theCold War(1947–1989). Russia's business tycoons developed strong ties with London financial institutions in the 1990s after thedissolution of the USSRin 1991. Due to the2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine,relations became very tense after the United Kingdom imposed sanctions against Russia. It was subsequently added to Russia'slist of "unfriendly countries".

The two countries share a history of intense espionage activity against each other, with the Soviet Union succeeding inpenetration of top echelonsof the British intelligence and security establishment in the 1930s–1950s while concurrently, the British co-opted top Russian intelligence officers throughout the period including the 1990s whereby British spies such asSergei Skripalacting within the Russian intelligence establishment passed on extensive details of their intelligence agents operating throughout Europe.[2]Since the 19th century, England has been a popular destination for Russian politicalexiles,refugees,and wealthy fugitives from theRussian-speakingworld.

In the early-21st century, especially following thepoisoning of Alexander Litvinenkoin 2006, relations became strained. In the early years ofDavid Cameronas UK Prime Minister, there was a brief uptick in relations, up until 2014.[3]Since 2014, relations have grown increasingly unfriendly due to theRusso-Ukrainian War(2014–present) and thepoisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripalin 2018. In the wake of the poisoning, 28 countries expelled suspected Russian spies acting as diplomats.[4]In June 2021, a confrontation occurred betweenHMSDefenderand theRussian Armed Forcesin the2021 Black Sea incident.

Following the2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine,relations between the twonuclear powerscollapsed entirely; the United Kingdomimposed economic sanctionson Russian outlets, seized the assets ofRussian oligarchs,recalled its citizens and severed all business ties with Russia.[5]Russia retaliated with its own sanctions against the UK and accused it of involvement in attacks againstSevastopol Naval Base,theNord Stream gas pipelineand theCrimean Bridge.[6][7]The UK is one of the largest donors of financial and military aid to Ukraine and was the first country in Europe to donate lethal military aid.[8][9]

Historical background[edit]

Relations 1553–1792[edit]

TheKingdom of EnglandandTsardom of Russiaestablished relations in 1553 when English navigatorRichard Chancellorarrived inArkhangelsk– at which timeMary Iruled England andIvan the Terribleruled Russia. He returned to England and was sent back to Russia in 1555, the same year theMuscovy Companywas established. The Muscovy Company held a monopoly over trade between England and Russia until 1698.Tsar Alexeiwas outraged by theExecution of Charles Iof England in 1649, and expelled all English traders and residents from Russia in retaliation.[10]

In 1697–1698 during theGrand Embassy of Peter Ithe Russian tsar visited England for three months. He improved relations and learned the best new technology especially regarding ships and navigation.[11]

TheKingdom of Great Britain(1707–1800) and later theUnited Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland(1801–1922) had increasingly important ties with theRussian Empire(1721–1917), after Tsar Peter I brought Russia into European affairs and declared himself an emperor. From the 1720s Peter invited British engineers to Saint Petersburg, leading to the establishment of a small but commercially influentialAnglo-Russianexpatriate merchant community from 1730 to 1921. During the series of general European wars of the 18th century, the two empires found themselves as sometime allies and sometime enemies. The two states fought on the same side duringWar of the Austrian Succession(1740–48), but on opposite sides duringSeven Years' War(1756–63), although did not at any time engage in the field.

Ochakov issue[edit]

Prime MinisterWilliam Pitt the Youngerwas alarmed atRussian expansion in Crimeain the 1780s at the expense of hisOttomanally.[12]He tried to get Parliamentary support for reversing it. In peace talks with the Ottomans, Russia refused to return the keyOchakov fortress.Pitt wanted to threaten military retaliation. However, Russia's ambassadorSemyon Vorontsovorganised Pitt's enemies and launched a public opinion campaign. Pitt won the vote so narrowly that he gave up and Vorontsov secured a renewal of the commercial treaty between Britain and Russia.[13][14]

Napoleonic Wars: 1792–1817[edit]

The outbreak of theFrench Revolutionand itsattendant warstemporarily united constitutionalist Britain and autocratic Russia in an ideological alliance againstFrench republicanism.Britain and Russia attempted to halt the French but the failure of theirjoint invasion of the Netherlandsin 1799 precipitated a change in attitudes.

Britain createdMalta Protectoratein 1800, while the EmperorPaul I of RussiawasGrand Master of the Knights Hospitaller.That led to the never-executedIndian March of Paul,which was a secret project of a planned allied Russo-French expedition against theBritish possessionsin India.

In 1805 both countries again attempted to combine operations with British expeditions to North Germany and Southern Italy in concert with Russian expeditionary corps were intended to create diversions in favour of Austria. However, several spectacular French victories in central Europe ended theThird Coalition.

Following the heavy Russian defeat atFriedland,Russia was obliged to enter Napoleon'scontinental system,barring all trade with Britain. Subsequently, both countries entered into a state of limited war, theAnglo-Russian War (1807–12),although neither side actively persecuted operations against each other.

In 1812 Britain and Russia once again became allies againstNapoleonin theNapoleonic Wars.The United Kingdom gave financial and material support to Russia during the French invasion in 1812, following which both countries pledged to keep 150,000 men in the field until Napoleon had been totally defeated. They both played major cooperative roles at theCongress of Viennain 1814–1815 establishing a twenty-year alliance to guarantee European peace.

Eastern Question, Great Game, Russophobia[edit]

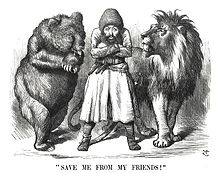

From 1820 to 1907, geopolitical disputes led to a gradual deterioration in Anglo-Russian relations. Popular sentiment in Britain turned increasingly hostile to Russia, with a high degree of anxiety for the safety ofBritish rule in India.The result was a long-standing rivalry inCentral Asia.[15]In addition, there was a growing concern that Russia would destabilise Eastern Europe by its attacks on the falteringOttoman Empire.This fear was known as theEastern Question.[16]Russia was especially interested in getting a warm water port that would enable its navy. Getting access out of the Black Sea into the Mediterranean was a goal, which meant access through the Straits controlled by the Ottomans.[17]

Both intervened in theGreek War of Independence(1821–1829), eventually forcing theLondon peace treatyon the belligerents. The events heightened BritishRussophobia.In 1851 theGreat Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nationsheld in London'sCrystal Palace,including over 100,000 exhibits from forty nations. It was the world's first international exposition. Russia took the opportunity to dispel Russophobia in Britain by refuting stereotypes of Russia as a backward, militaristic repressive tyranny. Its sumptuous exhibits of luxury products and large 'objets d'art' with little in the way of advanced technology, however, did little to change its reputation. Britain considered its navy too weak to worry about, but saw its large army as a major threat.[18]

The Russian pressures on the Ottoman Empire continued, leaving Britain and France to ally with the Ottomans and push back against Russia in theCrimean War(1853–1856). Russophobia was an element in generating popular support in Britain for the far-off conflict.[19]Public opinion in Britain, especially amongWhigs,supported Polish revolutionaries who were resistingRussian rule in Poland,after theNovember Uprisingof 1830. The British government watched nervously asSaint Petersburgsuppressed the subsequentPolish revoltsin the early 1860s, yet refused to intervene.[20][21]

London hosted the first Russian-language censorship-free periodicals —Polyarnaya Zvezda,Golosa iz Rossii, andKolokol( "The Bell" ) — were published byAlexander HerzenandNikolai Ogaryovin 1855–1865, which were of exceptional influence on Russian liberal intellectuals in the first several years of publication.[22]The periodicals were published by theFree Russian Pressset up by Herzen in 1853, on the eve of the Crimean War, financed by the funds Herzen had managed to expatriate from Russia with the help of his bankers, the Paris branch of theRothschild family.[23]

Hostile images and growing tensions[edit]

Russia's defeat in the Crimean War had been widely perceived by Russians as a humiliation and sharpened their desire for revenge. Tensions between the governments of Russia and Britain grew during the mid-century period. Since 1815 there had been an ideological cold war between reactionary Russia and liberal Britain. The Russians helpedAustriabrutally suppress the liberalHungarian revoltduring theRevolutions of 1848-49to the dismay of the British. Russian leaders felt their nation's leniency in the 1820s allowed liberalism to spread in the West.[24]

They deplored the liberalrevolutions of 1830inFrance,Belgium,central Europe; worst of all was the anti-Russian revolt that had to be crushed in Poland. New strategic and economic competition heightened tensions in the late 1850s, as the British moved into Asian markets. Russia's suppression of tribal revolts in the Caucasian region released troops for campaigns to expand Russian influence in central Asia, which the British interpreted as a long-term threat to theBritish Empirein India.[24]There was strong hostility among British government officials to the repeated Russian threats to the Ottoman Empire with the goal of controlling theDardanellesconnecting theBlack Seaand theMediterranean Sea.[25]

Beginning from the early 19th century, depictions of Russia in the British media, largely drawing on the reports of British travel writers and newspaper correspondents, frequently presented a "distorted picture" of the country; scholar Iwona Sawkowicz argues that this was due to the "brief visits" of these writers and correspondents, many of whom did not speakRussianand were "looking mostly for cultural differences." These depictions had the effect of increasing Russophobia in Britain despite growing economic and political ties between the two countries.[26]In 1874, tension lessened asQueen Victoria's second sonPrince AlfredmarriedTsar Alexander II's only daughterGrand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna,followed by a cordial state visit by the tsar. The goodwill lasted no more than three years, when structural forces again pushed the two nations to the verge of war.[27]

Panjdeh incident 1885[edit]

Anglo-Russian rivalries grew steadily over Central Asia during the so-called "Great Game"of the late 19th century.[28]Russia desired warm-water ports on theIndian Oceanwhile Britain wanted to prevent Russian troops from gaining a potential invasion route toIndia.[29]In 1885 Russia annexed part ofAfghanistanin thePanjdeh incident,which caused a war scare. After nearly completing theRussian conquest of Central Asia(Russian Turkestan) the Russians captured an Afghan border fort. Seeing a threat to India, Britain came close to threatening war but both sides backed down and the matter was settled by diplomacy.[30]

The effect was to stop further Russian expansion in Asia, except for thePamir Mountains,and to define the north-western border of Afghanistan. However, Russia's foreign ministerNikolay Girsand her ambassador to LondonBaron de Staalin 1887 set up a buffer zone in Central Asia. Russian diplomacy thereby won grudging British acceptance of its expansionism.[30]Persia was also an arena of tension, but without warfare.[31]

Far East, 1860–1917[edit]

Although Britain had serious disagreements with Russia regarding Russia's threat to the Ottoman Empire, and perhaps even to India, tensions were much lower in theFar East.London tried to maintain friendly relations in the 1860-1917 period and did reach a number of accommodations with Russia innortheastern Asia.Both nations were expanding in that direction. Russia built theTrans-Siberian Railwayin the 1890s, and the British were expanding their large-scale commercial activities inChinausingHong Kong,and thetreaty portsof China. Russia sought a year-round port south of its main base inVladivostok.[32][33]

The key ingredient was that both nations were more fearful of Japanese plans than they were of each other; they both saw the need to collaborate. They cooperated with each other (and France) in forcingJapanto disgorge some of its gains after it won theFirst Sino-Japanese Warof 1894. Russia increasingly became a protector of China against Japanese intentions. TheOpen Doorpolicy promoted by the United States and Britain was designed to allow all nations on an equal footing to trade with China and was accepted by Russia. All the major powers collaborated in theEight-Nation Alliancedefending their diplomats during theBoxer Rebellion.[32][33]

The British signed amilitary alliance with Japanin 1902, as well as anagreement with Russiain 1907 that resolved their major disputes. AfterRussia was defeated by Japanin 1905, those two countries work together on friendly terms to divide upManchuria.Thus by 1910 the situation among the great powers in the Far East was generally peaceful with no troubles in sight. When theFirst World War broke outin 1914, Britain, Russia, Japan and China all declared war on Germany, and cooperated in defeating and dividing up its Imperial holdings.[32][33]

At the same time, Russophilia flourished in Britain, founded on the popularity of Russian novelists such asLeo TolstoyandFyodor Dostoyevsky,and sympathetic views of Russian peasants.[34]

Following theassassination of Tsar Alexander IIin 1881, exiles from the radicalNarodnaya Volyaparty and other opponents of Tsarism found their way to Britain.Sergei StepniakandFelix Volkhovskyset up the Russian Free Press Fund, along with a journal, Free Russia, to generate support for reforms to, and abolition of, Russian autocracy. They were supported by liberal, nonconformist and left-wing Britons in the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom. There was also considerable support for victims of the Russian famine of 1891-2 and the Jewish and Christian victims of Tsarist persecution.[35]

Early 20th century[edit]

There was cooperation in Asia, however, as Britain and Russia joined many others to protect their interests in China during theBoxer Rebellion(1899–1901).[36]

Britain was an ally of Japan after 1902, but remained strictly neutral and did not participate in theRusso-Japanese Warof 1904–5.[37][38][39]However, there was a brief war scare in theDogger Bank incidentin October 1905 when theImperial Russian Navy'sBaltic Fleet,headed to thePacific Oceanto fight theImperial Japanese Navy,mistakenly engaged a number of British fishing vessels in theNorth Seafog. The Russians thought they were Japanese torpedo boats, and sank one, killing three fishermen. The British public was angry but Russia apologised and damages were levied through arbitration.[40]

Diplomacy became delicate in the early 20th century. Russia was troubled by theEntente Cordialebetween Great Britain and France signed in 1904. Russia and France already had a mutual defense agreement that said France was obliged to threaten Britain with an attack if Britain declared war on Russia, while Russia was to concentrate more than 300,000 troops on the Afghan border for an incursion into India in the event that Britain attacked France.[41]

The solution was to bring Russia into the British-French alliance. TheAnglo-Russian Ententeand theAnglo-Russian Convention of 1907made both countries part of theTriple Entente.[41]The Convention was a formal treaty demarcating British and Russian spheres of influence in Central Asia. It enabled Britain to focus on the growing threat from Germany at sea and in central Europe.[42]

The Convention ended the long-standing rivalry in central Asia, and then enabled the two countries to outflank the Germans, who were threatening to connectBerlintoBaghdadwith anew railroadthat would probably align the Turkish Empire with Germany. The Convention ended the long dispute overPersia.Britain promised to stay out of the northern half, while Russia recognised southern Persia as part of the British sphere of influence. Russia also promised to stay out of Tibet and Afghanistan. In exchange London extended loans and some political support.[43][44]The Convention led to the formation of theTriple Entente.[45]

Allies, 1907–1917[edit]

Both countries were then part of the subsequentallianceagainst theCentral PowersinWorld War I.In the summer of 1914,Austria-HungaryattackedSerbia,Russia promised to help Serbia, Germany promised to help Austria, and war broke out between Russia and Germany. France supported Russia. Under Foreign MinisterSir Edward GrayBritain felt its national interest would be badly hurt if Germany conqueredBelgiumand France. It was neutral untilGermany suddenly invaded Belgiumand France. Britain declared war becoming an ally of France and Russia against Germany and Austria.[46]

The alliance lasted when the February 1917 Revolution in Russia overthrewTsar Nicholas IIand theRussian monarchy.However When the Bolsheviks under Lenin took power in November, they made peace with Germany—theTreaty of Brest-Litovskwas in effect a surrender with massive loss of territory. Russia ended all diplomatic and trade relations with Britain, and repudiated all debts to London and Paris. The British supported theanti-Bolshevik forcesduring theRussian Civil War,but they lost, and Britain restored trade relations in 1921.[47]

British–Soviet relations[edit]

| |

Soviet Union |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

Interwar period[edit]

In 1918, with theGerman Armyadvancing toward Moscow inOperation Faustschlag,theRussian Soviet Federative Socialist Republicunder Lenin made many concessions to the German Empire in return for peace. The Allies felt betrayed by theTreaty of Brest Litovsksigned on 3 March 1918.[48]Towards theend of World War I,Britain began to send troops to Russia to participate in theAllied intervention in the Russian Civil Warwhich lasted up to 1925, aiming to topple the newly-formed socialist government the Bolsheviks had created. As late as 1920, Grigory Zinoviev called for a "holy war" againstBritish imperialismat a rally inBaku.[49]

Following the withdrawal of British troops from Russia, negotiations for trade began, and on 16 March 1921, theAnglo-Soviet Trade Agreementwas concluded between the two countries.[50]Lenin'sNew Economic Policydownplayed socialism and emphasised business dealings with capitalist countries, in an effort to restart the sluggishRussian economy.Britain was the first country to accept Lenin's offer of a trade agreement. It ended the British blockade, and Russian ports were opened to British ships. Both sides agreed to refrain from hostile propaganda. It amounted to de facto diplomatic recognition and opened a period of extensive trade.[51]

Britain formally recognised theUnion of Soviet Socialist Republics(USSR or Soviet Union, 1922–1991) on 1 February 1924.[52]However, Anglo-Soviet relations were still marked by distrust and contention, culminating in a diplomatic break in 1927. Diplomatic relations between the two countries were severed at the end of May 1927 after a police raid on theAll Russian Co-operative SocietywhereafterConservativeBritish Prime MinisterStanley Baldwinpresented theHouse of Commonswith deciphered Soviet telegrams that proved Soviet espionage activities.[53][54]The fallout from this incident contributed to theSoviet war scare of 1927,as it led to a domestic Soviet fear of an invasion, although the fear is generally considered by historians to have been created by Stalin to use against his opponents in theLeft Opposition.[55]After the1929 general election,the incomingLabourgovernment ofRamsay MacDonaldsuccessfully established permanent diplomatic relations.[56]

Second World War[edit]

In 1938, Britain and France negotiated theMunich AgreementwithNazi Germany.Stalin opposed the pact and refused to recognise the German annexation of theCzechoslovakSudetenland.

German-Soviet Non-aggression Pact[edit]

The USSR and Germany signed theNon-aggression Pactin late August 1939, which promised the Soviets control of about half of Eastern Europe, and removed the risk to Germany of atwo-front war.Germany invaded Polandon 1 September, and theSoviets followedsixteen days later. Many members of theCommunist Partyin Britain and sympathisers were outraged and quit. Those who remained strove to undermine the British war effort and campaigned for what the Party called a 'people's peace', i.e. a negotiated settlement with Hitler.[57][58]Britain, along with France, declared war on Germany, but not the USSR. The British people were sympathetic to Finland in herWinter Waragainst the USSR. The USSR furthermore supplied oil to the Germans which Hitler'sLuftwaffeneeded in itsBlitzagainst Britain in 1940.

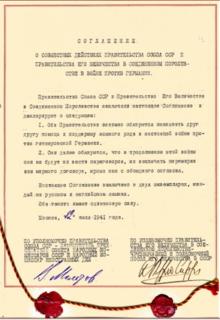

Anglo-Soviet alliance[edit]

In June 1941, Germany launchedOperation Barbarossa,attacking the USSR. Britain and the USSR agreed an alliance the following month with theAnglo-Soviet Agreement.TheAnglo-Soviet invasion of Iranin August overthrewReza Shahand secured the oil fields inIranfrom falling intoAxishands. TheArctic convoystransported supplies between Britain and the USSR during the war. Britain was quick to provide limitedmaterielaid to the Soviet Union – including tanks and aircraft – via these convoys in order to try to keep her new ally in the war against Germany and her allies.[59]

One major conduit for supplies was through Iran. The two nations agreed on a joint occupation of Iran, to neutralise German influence. After the war, there were disputes about the Soviet delayed departure from Iran, and speculation that it planned to set up a puppet state along its border. That problem was resolved completely in 1946.[60]The Soviet Union joined theSecond Inter-Allied Meetingin London in September. The USSR thereafter became one of the "Big Three"Allies of World War IIalong with Britain and, from December, the United States, fighting against theAxis Powers.

A twenty-year mutual assistance agreement, theAnglo-Soviet Treatywas signed in May 1942, reasserting themilitary allianceuntil the end of the war and formalizing apolitical alliancebetween theSoviet Unionand theBritish Empirefor 20 years.

In August 1942,Winston Churchill,accompanied by AmericanW. Averell Harriman,went to Moscow and met Stalin for the first time.The British were nervous that Stalin and Hitler might make separate peace terms; Stalin insisted that would not happen. Churchill explained how Arctic convoys bringing munitions to Russia had been intercepted by the Germans; there was a delay now so that future convoys would be better protected. He apologetically explained there would be no second front this year—no British-American invasion of France—which Stalin had been urgently requesting for months. The will was there, said Churchill, but there was not enough American troops, not enough tanks, not enough shipping, not enough air superiority. Instead the British, and soon the Americans, would step upbombing of German cities and railways.Furthermore, there would be "Operation Torch"in November. It would be a major Anglo-American invasion of North Africa, which would set the stage for aninvasion of Italyand perhaps open theMediterraneanfor munitions shipments to Russia through theBlack Sea.The talks started out on a very sour note but after many hours of informal conversations, the two men understood each other and knew they could cooperate smoothly.[61][62]

Polish boundaries[edit]

Stalin was adamant about British support for new boundaries for Poland, and Britain went along. They agreed that after victory Poland's boundaries would be moved westward, so that the USSR took over lands in the east while Poland gained lands in the west that had been under German control.

They agreed on the "Curzon Line"as the boundary between Poland and the Soviet Union) and theOder-Neisse linewould become the new boundary between Germany and Poland. The proposed changes angered thePolish government in exilein London, which did not want to lose control over its minorities. Churchill was convinced that the only way to alleviate tensions between the two populations was the transfer of people, to match the national borders. As he toldParliamenton 15 December 1944, "Expulsion is the method which... will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble.... A clean sweep will be made."[63]

Postwar plans[edit]

The U.S. and Britain each approached Moscow in its own way; there was little coordination. Churchill wanted specific, pragmatic deals, typified by the percentage arrangement. Roosevelt's highest priority was to have the Soviets eagerly and energetically participate in the newUnited Nations,and he also wanted them to enter thewar against Japan.[64]

In October 1944, Churchill and foreign ministerAnthony Edenmet Stalin and his foreign ministerVyacheslav Molotovin Moscow. They discussed who would control what in the rest of postwar Eastern Europe. The Americans were not present, were not given shares, and were not fully informed. After lengthy bargaining the two sides settled on along-term plan for the division of the region,the plan was to give 90% of the influence inGreeceto Britain and 90% inRomaniato Russia. Russia gained an 80%/20% division inBulgariaandHungary.There was a 50/50 division inYugoslavia.[65][66]

Cold War and beyond[edit]

Followingthe end of the Second World War,relations between the Soviet and theWestern Blocdeteriorated quickly. Former British Prime Minister Churchill claimed that the Soviet occupation ofEastern Europeafter World War II amounted to 'aniron curtainhas descended across the continent.' Relations were generally tense during the ensuingCold War,typified byspyingand other covert activities. The British and AmericanVenona Projectwas established in 1942 forcryptanalysisof messages sent bySoviet intelligence.Soviet spies were later discovered in Britain, such asKim Philbyand theCambridge Fivespy ring, which was operating in England until 1963.

The Soviet spy agency, theKGB,was suspected of the murder ofGeorgi Markovin London in 1978. A High ranking KGB official,Oleg Gordievsky,defected to London in 1985.

British prime ministerMargaret Thatcherpursued a stronganti-communistpolicy in concert withRonald Reaganduring the 1980s, in contrast with thedétentepolicy of the 1970s. During theSoviet–Afghan Warthe British conductedcovert military supportas well as sending arms and supplies to theAfghan Mujahideen.

Relations improved considerably afterMikhail Gorbachevcame to power in the Soviet Union in 1985 and launchedperestroika.They remained relatively warm after thecollapse of the USSRin 1991 – with Russia taking over the international obligations and status from the demised superpower.

In October 1994, Queen Elizabeth IImade a state visitto Russia, the first time a ruling British monarch had set foot on Russian soil.[67]

21st century[edit]

2000s[edit]

Relations between the countries began to grow tense again shortly afterVladimir Putinwas elected asPresident of the Russian Federationin 2000, with the Kremlin pursuing a more assertiveforeign policyand imposing more controls domestically. The major irritant in the early-2000s was the UK's refusal to extraditeRussian citizens,self-exiled businessmanBoris BerezovskyandChechenseparatist leaderAkhmed Zakayev,whom the UK grantedpolitical asylum.[68]

In late 2006, formerFSBofficerAlexander LitvinenkowaspoisonedinLondonby radioactive metalloid,Polonium-210and died three weeks later. The UK requested the extradition ofAndrei Lugovoyfrom Russia to face charges over Litvinenko's death. Russia refused, stating theirconstitutiondoes not allow extradition of their citizens to foreign countries. As a result of this, the United Kingdom expelled four Russian diplomats, shortly followed by Russia expelling four British diplomats.[69]The Litvinenko affair remains a major irritant in British-Russian relations.[70]In the aftermath of the Litvinenko poisoning, the UK's special security service agencies,MI5andMI6severed their relations, and co-operation with Russia's special security agency theFSB.[71]

In July 2007, theCrown Prosecution Serviceannounced thatBoris Berezovskywould not face charges in the UK for talking toThe Guardianabout plotting a "revolution" in his homeland.Kremlinofficials called it a "disturbing moment" in Anglo-Russian relations. Berezovsky remained a wanted man in Russia until his death in March 2013; having been accused ofembezzlementandmoney laundering.[72]

Russia re-commenced long range air patrols of theTupolev Tu-95bomber aircraft in August 2007. These patrols neared British airspace, requiringRAFfighter jets to "scramble"and intercept them.[73][74]

In January 2008, Russia ordered two offices of theBritish Councilsituated in Russia to shut down, accusing them of tax violations. Eventually, work was suspended at the offices, with the council citing "intimidation" by the Russian authorities as the reason.[75][76]However, later in the year a Moscow court threw out most of the tax claims made against the British Council, ruling them invalid.[77]

During the2008 South Ossetia warbetween Russia andGeorgia,then-UK Foreign Secretary,David Miliband,visited the Georgian capital city ofTbilisito meet with the Georgian President and said the UK's government and people "stood in solidarity" with the Georgian people.[78]

Earlier in 2009, then Solicitor-General,Vera Baird,personally decided that the property of theRussian Orthodox Churchin the United Kingdom, which had been the subject of a legal dispute following the decision of the administering Bishop and half its clergy and lay adherents to move to the jurisdiction of theEcumenical Patriarchate,would have to remain with theMoscow Patriarchate.She was forced to reassure concerned Members of Parliament that her decision had been made only on legal grounds, and that diplomatic and foreign policy questions had played no part. Baird's determination of the case was however endorsed by the Attorney-GeneralBaroness Patricia Scotland.It attracted much criticism. However, questions continue to be raised that Baird's decision was designed not to offend the Putin government in Russia.

In November 2009,David Milibandvisited Russia and described the state of relations between the two countries as "respectful disagreement".[79]

Meanwhile, both the UK and Russia declassified a large amount of contemporary material from the highest levels of the political power. In 2004, Alexander Fursenko of theRussian Academy of Sciences(RAS) and Arne Westad of theLondon School of Economicsstarted a project to disclose British–Soviet relations during theCold War.Four years, the project's direction passed to the historian Alexandr Chubarian, also a member of the RAS, who in 2016 completed the documentation covering from 1943 to 1953.[80]

2010s[edit]

In the years after David Cameron became UK Prime Minister, UK-Russia relations initially showed a marked improvement. In 2011, Cameron visited Russia, and in 2012, Putin visited the UK for the first time in seven years, holding talks with Cameron, and also visiting the2012 London Olympicstogether.[81]

In May 2013, Cameron flew to meet Putin at his summer residence inSochi,Bocharov Ruchei, to hold talks on theSyriacrisis. Cameron described the talks as "very substantive, purposeful and useful", and the leaders exchanged presents with each other. Cameron emphasised the 'commonalities between the two countries', and renewed cooperation between the countries' security services for the2014 Sochi Olympics.Camron stated at this time that a more effective relationship between the UK and Russia would "make people in both our countries safer and better off".[82]At that time, it was suggested that Cameron could use his good relations with both US PresidentBarack Obama,and President Putin to act as a 'go-between' in international relations.[83]

In 2014, relations soured drastically following theRusso-Ukrainian War,with the British government, along with the United States and the European Union, imposingpunitive sanctionson Russia. Cameron criticised the2014 Crimean status referendumas a "sham", with voters having "voted under the barrel of a kalashnikov", stating "Russia has sought to annex Crimea.... This is a flagrant breach of international law and something we will not recognise."[84]In March 2014, the UK suspended all military cooperation with Russia and halted all extant licences for direct military export to Russia.[85]In September 2014, there were more rounds of sanctions imposed by the EU, targeted atRussian bankingandoil industries,and at high officials. Russia responded by cutting off food imports from the UK and other countries imposing sanctions.[86]UK Prime Minister David Cameron and U.S. president Barack Obama jointly wrote forThe Timesin early September: "Russia has ripped up the rulebook with its illegal, self-declaredannexation of Crimeaand its troops on Ukrainian soil threatening and undermining a sovereign nation state. "[87][88]

In 2016, 52% of British people decided tovotein favor for the country's exit from theEuropean Union,which was known asBrexit.As shockwave were sent across the country, both Cameron and British officials accused Russia of meddling the vote.[89]Future British Prime Minister,Boris Johnson,was accused of being a Russian stooge and underestimating Russian interference.[90][91]

According to anIntelligence and security committee reportthe British government and intelligence agencies failed to conduct any proper assessment of Kremlin attempts to interfere with the Brexit referendum.[92]

In early 2017, during her meeting with U.S. presidentDonald Trump,the UK prime ministerTheresa Mayappeared to take a line harsher than that of the U.S. on the Russian sanctions.[93]In April 2017, Moscow's ambassador to the UKAlexander Yakovenkostrongly criticised the UK for "raising tensions in Europe" by deploying 800 troops to Estonia. Yakovenko stated that UK-Russia relations were at an "all-time low", adding that there was no longer any "bilateral relationship of substance" between the countries.[94]

In mid-November 2017, in herGuildhallspeech at the Lord Mayor's Banquet, prime minister May called Russia "chief among those today, of course" who sought to undermine the "open economies and free societies" Britain was committed to, according to her.[95][96]She went on to elaborate: "[Russia] is seeking to weaponise information. Deploying its state-run media organisations to plant fake stories and photo-shopped images in an attempt to sow discord in the West and undermine our institutions. So I have a very simple message for Russia. We know what you are doing. And you will not succeed."[95]In response, Russian parliamentarians said Theresa May was "making a fool of herself" with a "counterproductive" speech; Russia's embassy reacted to the speech by posting a photograph of her from the Banquet drinking a glass of wine, with the tweet: "Dear Theresa, we hope, one day you will try Crimean #Massandrared wine ".[97]Theresa May's Banquet speech was compared by some Russian commentators toWinston Churchill'sIron Curtain speechinFultonin March 1946;[98][99]it was hailed byAndrew Rosenthalin a front-page article run byThe New York Timesthat contrasted May's message against some statements about Putin made by Donald Trump, who, according to Rosenthal, "far from denouncing Putin's continuous assaults on human rights and free speech in Russia, [...] praised [Putin] as being a better leader than Barack Obama|Obama."[100]

In December 2017,Boris Johnsonbecame the firstUK foreign secretaryto visit Russia in five years. Johnson said that UK-Russia relations were "not on a good footing" but he "wanted them to improve", after talks in Moscow. Russia's foreign ministerSergei Lavrovaccused the UK of making "insulting" statements ahead of the meeting, adding that it was "was no secret that Britain's relations with Russia were at a 'low point'", but said he "trusted Mr Johnson" and the two countries had agreed on the need to work together on theUN Security Council.[101]

In March 2018, as a result of thepoisoning of Sergei and Yulia SkripalinSalisbury,relations between the countries deteriorated still further, both countries expelling 23 diplomats each and takingother punitive measuresagainst one another. Within days of the incident, the UK government's assessment that it was "highly likely" that the Russian state was responsible for the incident received the backing of the EU, the US, and Britain's other allies.[102][103][104][105]In what the Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson called the "extraordinary international response" on the part of the UK's allies, on 26 and 27 March 2018 there followed a concerted action by the U.S., most of the EU member states,Albania,Australia,Canada,Macedonia,Moldova,andNorway,as well as NATO to expel a total of over 140 Russian accredited diplomats (including those expelled by the UK).[106][107]

Additionally, in July 2018, the COBR committee were assembled following a poisoning of two other British citizens in the town ofAmesbury,not far fromSalisbury,the location of the Skripals' poisoning. It was later confirmed byPorton Downthat the substance was aNovichok agent.Sajid Javid,the United Kingdom's home secretary insisted in the house of commons that he was letting the investigation teams conduct a full investigation into what had happened before jumping to a major conclusion. He then re-iterated the initial question to Russia regarding the Novichok agent, accusing them of using the United Kingdom as a 'dumping ground'.[108]

In his speech at theRUSI Land Warfare Conferencein June 2018, theChief of the General StaffMark Carleton-Smithsaid that British troops should be prepared to "fight and win" against the "imminent" threat of hostileRussia.[109][110]Carleton-Smith said: "The misplaced perception that there is no imminent or existential threat to the UK – and that even if there was it could only arise at long notice – is wrong, along with a flawed belief that conventional hardware and mass are irrelevant in countering Russian subversion...".[110][111]In a November 2018 interview with theDaily Telegraph,Carleton-Smith said that "Russia today indisputably represents a far greater threat to our national security than Islamic extremist threats such asal-QaedaandISIL.... We cannot be complacent about the threat Russia poses or leave it uncontested. "[112]

Conservative Party leader Boris Johnson's victory in the2019 United Kingdom general electionreceived a mixed response from Russia. Press SecretaryDmitry Peskovquestioned "how appropriate... hopes are in the case of the Conservatives" of good relations following the election.[113]However, Putin praised Johnson, stating that "he felt the mood of British society better than his opponents".[114]

2020s[edit]

In March 2020, the British government declared Russia the most "acute" threat to UK security in theIntegrated Review,which defines the government's foreign, defence, security and international development policies.[115]

In June 2021, a confrontation occurred betweenHMSDefender(D36)and theRussian Armed Forcesin the2021 Black Sea incident.[116]

Russian invasion of Ukraine[edit]

In response to theRussian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022the UK government applied economic sanctions on Russian banks and individual citizens and bannedAeroflotaeroplanes from entering British airspace, in retaliation the Russian government banned British aeroplanes from entering Russian airspace.[117]

Britain also supplied the Ukrainians with military equipment; most notably sendingNLAWmissiles to Ukraine, commencing in January 2022 in anticipation of the Russian invasion.[118]As of 16 March 2022, the UK confirmed that it had delivered more than 4,000 NLAWs to Ukraine.[119]In addition the UK commenced supplying Ukraine withStarstreakmissiles (HVM) to help prevent Russian air supremacy. British soldiers were sent via Poland to help train Ukrainian forces.[120][121]These were sent as an interim measure until the arrival of theSky Sabremissile defence system.[122]

On 26 February 2022, Britain and its partners took "decisive action" to block Russia's banks' access to theSWIFTinternational payment system, according to British Prime Minister Boris Johnson.[123]

On 5 March 2022, Britain again issued statements condemning Russia's actions in Ukraine, and also urged its citizens to consider leaving the country. "If your presence in Russia is not essential, we strongly advise that you consider leaving by remaining commercial routes," announced the British government in a statement.[124]On 11 March 2022, the United Kingdom imposed sanctions on 386 members of Russia's lower house of parliament and announced that it would attempt to prohibit the export of luxury products to Russia in order to raise diplomatic pressure on Russian President Vladimir Putin over the invasion of Ukraine.[125]On 12 March 2022, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany cautioned Russia that its demands for economic guarantees with Iran could jeopardize an almost-completed nuclear deal.[126]On 17 March 2022, the United Kingdom said it had "very, very strong evidence" of war crimes in Ukraine, and that Russian President Vladimir Putin was orchestrating them.[127]

On 24 March 2022, theKremlindeclared Prime Minister Boris Johnson as the most active anti-Russian leader. Downing Street rejected these claims and stated that the Prime Minister was "anti-Putin" and had no issue with the Russian people.[129]

On 3 May 2022, Russia aired a segment titledThe Sinkable Island.During the segment, hosted byDmitry Kiselyov,a simulation showing a hypothetical nuclear attack onGreat Britainwas shown.[130]On 8 May 2022, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson's office stated that G7 leaders agreed that the world should increase economic pressure on Russian President Vladimir Putin in whatever manner feasible.[131]

Besides supplying lethal aid to Ukraine, the UK has stated intent to mobilise for the possible event of direct involvement in a broader conflict with Russia as announced byGeneral Sir Patrick Sanderson 28 June 2022 in what was known as Operation Mobilise.[132][133]In July 2022, the UK sanctioned its own citizen, journalistGraham Phillips,who had been reporting from the Russian side, for his work which "supports and promotes actions and policies which destabilise Ukraine and undermine or threaten the territorial integrity, sovereignty, or independence of Ukraine."[134]

On 29 September 2022, a RussianSu-27fighter "released" a missile in the vicinity of a Royal Air ForceBoeing RC-135 Rivet Jointwhich was carrying out a routine patrol over the Black Sea. Both the UK and Russia agreed that it was due to a technical malfunction, rather than a deliberate escalation. Patrols were temporarily suspended by the RAF following the incident but later resumed with fighter escorts.[135]

On 29 October 2022, Russia accused the UK of involvement in the2022 Nord Stream pipeline sabotage,which it claimed were carried out by the Royal Navy, in addition to involvement in the drone strikes on theSevastopol Naval Base.The UK Ministry of Defence released a statement denouncing the claims and stated that Russia was "peddling lies on an epic scale".[7]Earlier in the month, Russia had also accused the UK of involvement in theCrimean Bridge explosion.[6]

The appointment ofRishi Sunakas UK Prime Minister in October 2022 did not change the UK's anti-Russian position, and policies. In May 2023 at the annualG7summit, inTokyo,Sunak stepped up sanctions on Russia, banning the import of Russian diamonds, along with Russian-origin copper, aluminium and nickel, as he redoubled UK support for Ukraine. The UK also sanctioned a further 86 Russian individuals and companies.[136]

Espionage and influence operations[edit]

In June 2010, UK intelligence officials were saying that Russian spying activity in the UK was back at the Cold War level and thatMI5had been for a few years building up its counter-espionage capabilities against Russians; it was also noted that Russia's focus was "largely directed on expatriates."[137]In mid-August 2010, SirStephen Lander,Director-General ofMI5(1996–2002), said this of the level of Russian intelligence's activity in the UK: "If you go back to the early 90s, there was a hiatus. Then the spying machine got going again and theSVR[formerly the KGB], they've gone back to their old practices with a vengeance. I think by the end of the last century they were back to where they had been in the Cold War, in terms of numbers. "[138]

Directing non-domestic policy within overseas intelligence is a key but not a sole purpose of such information, its capability based on the information it can act on needs to be understood on its own. Separating its own capability from that gained from intelligence outsourcing and thus serves its purpose as explained.

In January 2012,Jonathan Powell,prime ministerTony Blair'schief of staffin 2006, admitted Britain was behind a plot to spy on Russia with a device hidden in a fake rock that was discovered in 2006 in a case that was publicised by Russian authorities; he said: "Clearly they had known about it for some time and had been saving it up for a political purpose."[139][140]Back in 2006, the Russian security service, the FSB, linked the rock case to British intelligence agents making covert payments to NGOs in Russia; shortly afterwards, president Vladimir Putin introduced a law thattightened regulation of funding non-governmental organisations in Russia.[141]

Embassies[edit]

TheEmbassy of Russiais located inLondon, United Kingdom.TheEmbassy of the United Kingdomis located inMoscow, Russia.

Outside Moscow, there is one BritishConsulate-GeneralinYekaterinburg.There was aBritish Consulate GeneralinSt. Petersburgbut it was closed in 2018 due to a diplomatic fallout following theSkripals affair.[142]There is a Russian Consulate General in Edinburgh.

See also[edit]

- Russian money in London

- Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

- Foreign policy of the Russian Empireto 1917

- Foreign policy of Vladimir Putin

- History of Russia

- International relations, 1648–1814

- International relations (1814–1919)

- International relations (1919–1939)

- Diplomatic history of World War II

- Cold War

- Embassy of Russia, London

- List of ambassadors of Russia to the United Kingdom

- List of Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Russia

- Timeline of British diplomatic history

- Anti-Russian sentiment

- Anti-British sentiment

- Cold War II

- Russian interference in British politics

- Soviet Union–United Kingdom relations

- Ukraine–United Kingdom relations

Minorities[edit]

(Anglo-Russians,Scottish RussiansandIrish Russians)

References[edit]

- ^Anglo-Russian RelationsHouse of Commons Hansard.

- ^"Sergei Skripal: Who is the former Russian intelligence officer?".BBC news.29 March 2018.Retrieved27 February2022.

- ^"David Cameron says 'real progress' made with Vladimir Putin over Syria".The Telegraph.10 May 2013.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^"Russia says it could have been in interests of Britain to poison Sergei Skripal".The Independent.2 April 2018.Retrieved10 November2018.

The Kremlin has reacted angrily to the expulsion of Russian diplomats by Britain and its allies, starting tit-for-tat expulsions.

- ^"Russian invasion of Ukraine: UK government response".GOV.UK.Government of the United Kingdom.Retrieved6 March2022.

- ^ab"Kerch Bridge, Nord Stream the handiwork of top-tier saboteurs".Asia Times.15 October 2022.Retrieved29 October2022.

- ^ab"Russia accuses 'British experts' of aiding drone attacks on Black Sea fleet".The Daily Telegraph.29 October 2022.Retrieved29 October2022.

- ^"UK to gift multiple-launch rocket systems to Ukraine".GOV.UK.6 June 2022.Retrieved29 October2022.

- ^"Where Military Aid to Ukraine Comes From".Statistica.Retrieved29 October2022.

- ^Sebag Montefiore, Simon(2016).The Romanovs.United Kingdom: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 48–49.

- ^Jacob Abbott(1869).History of Peter the Great, Emperor of Russia.Harper. pp. 141–51.

- ^John Holland Rose,William Pitt and national revival(1911) pp 589-607.

- ^Jeremy Black(1994).British Foreign Policy in an Age of Revolutions, 1783-1793.Cambridge UP. p. 290.ISBN9780521466844.

- ^John Ehrman,The Younger Pitt: The Reluctant Transition(1996) [vol 2] pp xx.

- ^Gerald Morgan,Anglo-Russian Rivalry in Central Asia, 1810-1895(1981).

- ^John Howes Gleason,The Genesis of Russophobia in Great Britain: A Study of the Interaction of Policy and Opinion(1950)online

- ^C.W. Crawley, "Anglo-Russian Relations 1815-40.Cambridge Historical Journal 3.1 (1929) 47-73.in JSTOR

- ^Anthony Swift, "Russia and the Great Exhibition of 1851: Representations, perceptions, and a missed opportunity."Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas(2007): 242-263, in English.

- ^Andrew D. Lambert,The Crimean War: British Grand Strategy Against Russia, 1853-56(2011).

- ^L. R. Lewitter, "The Polish Cause as seen in Great Britain, 1830–1863."Oxford Slavonic Papers(1995): 35-61.

- ^K. W. B. Middleton,Britain and Russia(1947) pp 47–91.Online

- ^David R. Marples.″Lenin's Revolution: Russia 1917–1921.″ Pearson Education, 2000, p.3.

- ^Helen Williams. ″Ringing the Bell: Editor–Reader Dialogue in Alexander Herzen's Kolokol″.Book History4 (2001), p. 116.

- ^ab:Laurence Guymer. "Meeting Hauteur with Tact, Imperturbability, and Resolution: British Diplomacy and Russia, 1856–1865,"Diplomacy & Statecraft29:3 (2018), 390-412, DOI:10.1080/09592296.2018.1491443

- ^Roman Golicz, "The Russians shall not have Constantinople: English Attitudes to Russia, 1870–1878",History Today(November 2003) 53#9 pp 39-45.

- ^Iwona Sakowicz, "Russia and the Russians opinions of the British press during the reign of Alexander II (dailies and weeklies)."Journal of European studies35.3 (2005): 271-282.

- ^SirSidney Lee(1903).Queen Victoria.p. 421.

- ^Rodric Braithwaite,"The Russians in Afghanistan."Asian Affairs42.2 (2011): 213-229.

- ^David Fromkin,"The Great Game in Asia,"Foreign Affairs(1980) 58#4 pp. 936-951in JSTOR

- ^abRaymond Mohl, "Confrontation in Central Asia"History Today19 (1969) 176-183

- ^Firuz Kazemzadeh,Russia and Britain in Persia, 1864-1914: A Study in Imperialism(Yale UP, 1968).

- ^abcIan Nish, "Politics, Trade and Communications in East Asia: Thoughts on Anglo-Russian Relations, 1861–1907."Modern Asian Studies21.4 (1987): 667-678.Online

- ^abcDavid J. Dallin,The Rise of Russia in Asia(1949) pp 59-61, 36-39, 87-122.

- ^Martin Malia, Russia Under Western Eyes (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2000)

- ^Luke Kelly, British Humanitarian Activity and Russia, 1890-1923 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017)

- ^Alena N. Eskridge-Kosmach, "Russia in the Boxer Rebellion."Journal of Slavic Military Studies21.1 (2008): 38-52.

- ^B. J. C. McKercher, "Diplomatic Equipoise: The Lansdowne Foreign Office the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, and the Global Balance of Power."Canadian Journal of History24#3 (1989): 299-340.online

- ^Keith Neilson,Britain and the last tsar: British policy and Russia, 1894-1917(Oxford UP, 1995) p 243.

- ^Keith Neilson, "'A dangerous game of American Poker': The Russo‐Japanese war and British policy."Journal of Strategic Studies12#1 (1989): 63-87.online

- ^Richard Ned Lebow,"Accidents and Crises: The Dogger Bank Affair."Naval War College Review31 (1978): 66-75.

- ^abBeryl J. Williams, "The Strategic Background to the Anglo-Russian Entente of August 1907."Historical Journal9#3 (1966): 360-73.online.

- ^Cadra P. McDaniel, "Crossroads of Conflict: Central Asia and the European Continental Balance of Power."Historian73#1 (2011): 41-64.

- ^Barbara Jelavich,St. Petersburg and Moscow: Tsarist And Soviet Foreign Policy, 1814-1974(1974), pp 247-49, 254-56.

- ^Ewen W. Edwards, "The Far Eastern Agreements of 1907."Journal of Modern History26.4 (1954): 340-355.Online

- ^Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.Anglo-Russian Entente

- ^Neilson,Britain and the last tsar: British policy and Russia, 1894-1917(1995).

- ^Richard H. Ullman,Anglo-Soviet Relations, 1917-1921: Intervention and the War(1961).

- ^Robert Service(2000).Lenin: A Biography.Pan Macmillan. p. 342.ISBN9780330476331.

- ^Steiner, Zara (2005).The lights that failed: European international history, 1919-1933.Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-151881-2.OCLC86068902.

- ^Text inLeague of Nations Treaty Series,vol. 4, pp. 128–136.

- ^Christine A. White,British and American Commercial Relations with Soviet Russia, 1918-1924(U of North Carolina Press, 1992).

- ^"Recognition of Russia".Evening Star.Press Association. 2 February 1924. p. 4.Retrieved28 December2021.

- ^Christopher Andrew,"Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of Mi5" (London, 2009), p. 155.

- ^For an account of the break in 1927, see Roger Schinness, "The Conservative Party and Anglo-Soviet Relations, 1925–27",European History Quarterly7, 4 (1977): 393–407.

- ^Sontag, John P. (1975)."The Soviet War Scare of 1926-27".The Russian Review.34(1): 66–77.doi:10.2307/127760.ISSN0036-0341.JSTOR127760.

- ^Brian Bridges, "Red or Expert? The Anglo–Soviet Exchange of Ambassadors in 1929." Diplomacy & Statecraft 27.3 (2016): 437-452.

- ^Robert Manne,"Some British Light on the Nazi-Soviet Pact."European History Quarterly11.1 (1981): 83-102.

- ^Francis Beckett,Enemy Within: The Rise And Fall of the British Communist Party(John Murray, 1995)

- ^Hill, Alexander (2007). "British Lend Lease Aid and the Soviet War Effort, June 1941-June 1942".The Journal of Military History.71(3): 773–808.doi:10.1353/jmh.2007.0206.JSTOR30052890.S2CID159715267.

- ^S. Monin, "'The Matter of Iran Came Off Well Indeed'"International Affairs: A Russian Journal of World Politics, Diplomacy & International Relations(2011) 57#5 pp 220-231

- ^William Hardy McNeill,America, Britain and Russia: Their Cooperation and Conflict 1941-1946(1953) pp 197-200.

- ^John Lukacs,"The importance of being Winston."The National Interest111 (2011): 35-45online.

- ^Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches, 1897–1963(1974) vol 7 p 7069

- ^Martin Folly, "'A Long, Slow and Painful Road': The Anglo-American Alliance and the Issue of Co-operation with the USSR from Teheran to D-Day."Diplomacy & Statecraft23#3 (2012): 471-492.

- ^Albert Resis,"The Churchill-Stalin Secret" Percentages "Agreement on the Balkans, Moscow, October 1944,"American Historical Review(1978) 83#2 pp. 368–387in JSTOR

- ^Klaus Larres,A companion to Europe since 1945(2009) p. 9

- ^Shapiro, Margaret (18 October 1994)."Elizabeth II Visits Russia on Wave of Royal Gossip".The Washington Post.Archivedfrom the original on 19 September 2022.Retrieved19 September2022.

- ^"Mood for a fight in UK-Russia row".BBC News.14 January 2008.Retrieved15 April2016.

- ^"Russia expels four embassy staff".BBC News.19 July 2007.Retrieved15 April2016.

- ^"Двусторонние отношения".Retrieved25 December2019.

- ^"David Cameron says 'real progress' made with Vladimir Putin over Syria".The Daily Telegraph.10 May 2013.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^Anglo-Russian relations[1]7 April 2008

- ^"BBC Media Player".Retrieved25 December2019.

- ^"Russia's Bear bomber returns".BBC News.10 September 2007.Retrieved15 April2016.

- ^"Russia to limit British Council".BBC News.12 December 2007.Retrieved15 April2016.

- ^"Russia actions 'stain reputation'".BBC News.17 January 2008.Retrieved15 April2016.

- ^"British Council wins Russia fight".BBC News.17 October 2008.Retrieved2 May2010.

- ^"Miliband in Georgia support vow".BBC News.19 August 2008.Retrieved24 August2008.

- ^Kendall, Bridget (3 November 2009)."'Respectful disagreement' in Moscow ".BBC News.Retrieved2 May2010.

- ^Pechatnov, Vladimir; Rajak, Svetozar (1 July 2016)."British-Soviet relations in the Cold War, 1943-1953 documentary evidence project. British-Soviet Relations in the Cold War, 1943-1953 Documentary Evidence Project".Second World War (Academic Project)(in English and Russian). Russian Academy of Sciences, British Academy and LSE IDEAS: Abstract.Archivedfrom the original on 20 July 2021.Retrieved20 July2021.

- ^"Vladimir Putin and David Cameron find common ground but no action on Syria".The Guardian.2 August 2012.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^"Cameron claims talks with Putin on Syria are proving 'purposeful'".The Guardian.10 May 2013.Retrieved11 December2023.

- ^"David Cameron hails talks with Russia over Syria as 'purposeful and useful'".The Daily Telegraph.10 May 2013.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^"Ukraine crisis: David Cameron attacks Crimea vote 'under barrel of a Kalashnikov'".The Independent.21 March 2014.Retrieved11 December2023.

- ^"UK suspends Military and Defense Ties with Russia over Crimea Annexure".Biharprabha News. Indo-Asian News Service.Retrieved19 March2014.

- ^"Ukraine crisis: Russia and sanctions".BBC News.13 September 2014.

- ^Cameron, David; Obama, Barack (4 September 2014)."We will not be cowed by barbaric killers".The Times.

- ^Croft, Adrian; MacLellan, Kylie (4 September 2014)."NATO shakes up Russia strategy over Ukraine crisis".Reuters.

- ^Rosenberg, Steve (26 June 2016)."EU referendum: What does Russia gain from Brexit?".BBC.Retrieved15 December2019.

- ^"Russia report: Government 'underestimated' threat and 'clearly let us down'".ITV News.21 July 2020.Retrieved4 December2020.

- ^"PM accused of cover-up over report on Russian meddling in UK politics".The Guardian.4 November 2019.Retrieved23 June2021.

- ^Russia report reveals UK government failed to investigate Kremlin interference

- ^Smith, David (27 January 2017)."Trump and May appear at odds over Russia sanctions at White House visit".The Guardian.

- ^"Ties between UK and Russia have plummeted to an all-time low".17 April 2017.Retrieved11 December2023.

- ^abPM speech to the Lord Mayor's Banquet 2017gov.uk, 13 November 2017.

- ^Theresa May accuses Vladimir Putin of election meddlingBBC, 14 November 2017.

- ^Russian politicians dismiss PM's 'election meddling' claimsBBC, 14 November 2017.

- ^ереза Мэй пытается спасти Британию, вызывая дух ПутинаRIA Novosti,15 November 2017.

- ^Леонид Ивашов. Фултонская речь Терезы Мэйinterview of GenLeonid Ivashov.

- ^This is How Grown-Ups Deal With PutinThe New York Times,14 November 2017 (print edition on 16 November 2017).

- ^"Johnson urges better Russia relations".BBC News.22 December 2017.Retrieved22 December2017.

- ^EU leaders back Britain in blaming Russia over spy poisoningThe Washington Post, 22 March 2018.

- ^Walker, Peter; Roth, Andrew (15 March 2018)."UK, US, Germany and France unite to condemn spy attack".The Guardian.London.Retrieved15 March2018.

- ^"Salisbury attack: Joint statement from the leaders of France, Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom".Government of the United Kingdom. 15 March 2018.Retrieved23 March2018.

- ^European Council conclusions on the Salisbury attackEuropean Council, 22 March 2018.

- ^Spy poisoning: Nato expels Russian diplomatsBC, 27 March 2018.

- ^Putin's missteps over the Russian spy murderCNN, 27 March 2018.

- ^"Amesbury poisoning: Russia using UK as 'dumping ground'",BBC News, 1 July 2018

- ^"General Mark Carleton-Smith discusses Russia, AI, and developing capability".UK Defence Journal.20 June 2018.

- ^ab"CGS Keynote Address 2018".Royal United Services Institute.

- ^"Russia is preparing for war, British military experts warn".Daily Mirror.20 June 2018.

- ^"Russia poses greater threat to Britain than Isil, says new Army chief".The Daily Telegraph.23 November 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^"World leaders react to Boris Johnson's British election victory".Reuters.13 December 2019.

- ^"Putin praises Boris Johnson's Brexit crusade".Yahoo! News.13 December 2019.

- ^"Global Britain in a competitive age"(PDF).HM Government.Retrieved24 March2022.

- ^Fisher, Lucy; Sheridan, Danielle (24 June 2021)."Dominic Raab warned MoD about Royal Navy's Crimea plans".The Daily Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on 12 January 2022.Retrieved27 June2021.

- ^Therrien, Alex (24 February 2022)."Ukraine conflict: UK sanctions target Russian banks and oligarchs".BBC News.Retrieved25 February2022.

- ^Haynes, Deborah (20 January 2022)."Russia-Ukraine tensions: UK sends 30 elite troops and 2,000 anti-tank weapons to Ukraine amid fears of Russian invasion".London, United Kingdom:Sky News.Archivedfrom the original on 20 January 2022.Retrieved21 January2022.

- ^Wallace, Ben (16 March 2022)."Defence Secretary meets NATO Defence Minister in Brussels".GOV.UK.London, United Kingdom.Ministry of Defence.Archivedfrom the original on 16 March 2022.Retrieved18 March2022.

- ^"UK supplying starstreak anti-aircraft missiles to Ukraine, defence minister Wallace tells BBC".Reuters.16 March 2021.Retrieved16 March2022.

- ^Parker, Charlie."British Starstreak that can tear a MIG apart".The Times.Retrieved22 March2022.

- ^"UK showcases missile systems to send to Poland".BFBS.21 March 2022.Retrieved21 March2022.

- ^"PM Johnson says UK and allies have taken decisive action against Russia over SWIFT".Reuters.27 February 2022.Retrieved27 February2022.

- ^Schomberg, William; Heavens, Louise."Britain urges its nationals to consider leaving Russia".Reuters.Retrieved6 March2022.

- ^James, William (11 March 2022)."UK imposes sanctions on Russian lawmakers who supported Ukraine breakaway regions".Reuters.Retrieved13 March2022.

- ^"France, UK, Germany say Iran deal could collapse on Russian demands".Reuters.12 March 2022.Retrieved13 March2022.

- ^"UK says there is 'very very strong evidence' Russia's Putin behind war crimes in Ukraine".Reuters.17 March 2022.Retrieved20 March2022.

- ^"Russia outlines plan for 'unfriendly' investors to sell up at half-price".Reuters.30 December 2022.

- ^"Kremlin says UK's Johnson is most active anti-Russian leader - RIA".Reuters.24 March 2022.Retrieved24 March2022.

- ^"Russian propaganda TV shows airs simulation of nukes striking Great Britain".Fortune.Retrieved5 May2022.

- ^"G7 agrees to intensify economic pressure on Putin, UK PM says".Reuters.8 May 2022.Retrieved9 May2022.

- ^Romaniello, Federica (28 June 2022)."Operation MOBILISE: Army's new primary focus".Forces.BFBS.Retrieved14 June2024.

- ^"British army to mobilize to 'prevent war' in Europe, army chief says".Anadolu Agency.28 June 2022.Retrieved14 June2024.

- ^"British pro-Kremlin video blogger added to UK government Russia sanctions list".The Guardian.26 July 2022.Retrieved11 December2023.

- ^"Russian jet 'released missile' near RAF aircraft during patrol over Black Sea".Sky News.20 October 2022.Retrieved22 October2022.

- ^"Rishi Sunak announces ban at G7 on Russian diamonds, copper, aluminium and nickel".Sky News.19 May 2023.Retrieved12 December2023.

- ^Russian spies in UK ′at Cold War levels′, says MI5.The Guardian.29 June 2010.

- ^"Russia's intelligence attack: The Anna Chapman danger"BBC News,17 August 2010.

- ^Jonathan Powell comes clean over plot to spy on RussiansThe Independent, 19 January 2012.

- ^Британия признала, что использовала "шпионский камень"BBC, 19 January 2012.

- ^"UK spied on Russians with fake rock".BBC News.19 January 2012.Retrieved3 December2023.

- ^"Russia spy poisoning: 23 UK diplomats expelled from Moscow".BBC News.17 March 2018.Retrieved13 June2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Anderson, M. S.Britain's Discovery of Russia 1553–1815(1958). *Chamberlain, Muriel E.Pax Britannica?: British Foreign Policy 1789–1914(1989)

- Clarke, Bob.Four Minute Warning: Britain's Cold War(2005)

- Crawley, C. W. "Anglo-Russian Relations 1815-40"Cambridge Historical Journal(1929) 3#1 pp. 47–73online

- Cross, A. G. ed.Great Britain and Russia in the Eighteenth Century: Contacts and Comparisons. Proceedings of an international conference held at the University of East Anglia,Norwich, England, 11–15 July 1977 (Newtonville, MA: Oriental Research Partners, 1979).toc

- Cross, A. G. ed.The Russian Theme in English Literature from the Sixteenth Century to 1980: An Introductory Survey and a Bibliography(1985).

- Cross, A. G.By the Banks of the Thames: Russians in 18th century Britain(Oriental Research Partners, 1980)

- Dallin, David J.The Rise of Russia in Asia(1949)online

- Figes, Orlando.The Crimean War: A History(2011)excerpt and text search,scholarly history

- Fuller, William C.Strategy and Power in Russia 1600–1914(1998)

- Gleason, John Howes.The Genesis of Russophobia in Great Britain: A Study of the Interaction of Policy and Opinion(1950)

- Guymer, Laurence. "Meeting Hauteur with Tact, Imperturbability, and Resolution: British Diplomacy and Russia, 1856–1865,"Diplomacy & Statecraft29:3 (2018), 390–412, DOI:10.1080/09592296.2018.1491443

- Horn, David Bayne.Great Britain and Europe in the eighteenth century(1967), covers 1603 to 1702; pp 201–36.

- Ingram, Edward. "Great Britain and Russia," pp 269–305 in William R. Thompson, ed.Great power rivalries(1999)online

- Jelavich, Barbara.St. Petersburg and Moscow: Tsarist and Soviet foreign policy, 1814–1974(1974)online

- Klimova, Svetlana. "'A Gaul Who Has Chosen Impeccable Russian as His Medium': Ivan Bunin and the British Myth of Russia in the Early 20th Century." inA People Passing Rude: British Responses to Russian Culture(2012): 215-230online.

- Macmillan, Margaret.The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914(2013) cover 1890s to 1914; see esp. ch 2, 5, 6, 7.

- Meyendorff, A. F. (November 1946)."Anglo-Russian trade in the 16th century".The Slavonic and East European Review.25(64).

- Middleton, K.W.B.Britain and Russia: An Historical essay(1947) Narrative history 1558 to 1945online

- Morgan, Gerald, and Geoffrey Wheeler.Anglo-Russian Rivalry in Central Asia, 1810–1895(1981)

- Neilson, Keith.Britain and the Last Tsar: British Policy and Russia, 1894–1917(1995)

- Nish, Ian. "Politics, Trade and Communications in East Asia: Thoughts on Anglo-Russian Relations, 1861–1907."Modern Asian Studies21.4 (1987): 667–678.Online

- Pares, Bernard."The Objectives of Russian Study in Britain."The Slavonic Review(1922) 1#1: 59-72online.

- Sergeev, Evgeny.The Great Game, 1856–1907: Russo-British Relations in Central and East Asia(Johns Hopkins UP, 2013).

- Szamuely, Helen. "The Ambassadors"History Today(2013) 63#4 pp 38–44. Examines the Russian diplomats serving in London, 1600 to 1800. Permanent embassies were established in London and Moscow in 1707.

- Thornton, A.P. "Afghanistan in Anglo-Russian Diplomacy, 1869-1873"Cambridge Historical Journal(1954) 11#2 pp. 204–218online.

- Williams, Beryl J. "The Strategic Background to the Anglo-Russian Entente of August 1907."Historical Journal9#3 (1966): 360–373.

UK-USSR[edit]

- Bartlett, C. J.British Foreign Policy in the Twentieth Century(1989)

- Bell, P. M. H.John Bull and the Bear: British Public Opinion, Foreign Policy and the Soviet Union 1941–45(1990).online free to borrow

- Beitzell, Robert.The uneasy alliance; America, Britain, and Russia, 1941-1943(1972)online

- Bevins, Richard, and Gregory Quinn. ‘Blowing Hot and Cold: Anglo-Soviet Relations’, inBritish Foreign Policy, 1955-64: Contracting Options,eds. Wolfram Kaiser and Gilliam Staerck, (St Martin’s Press, 2000) pp 209–39.

- Bridges, Brian. "Red or Expert? The Anglo–Soviet Exchange of Ambassadors in 1929."Diplomacy & Statecraft27.3 (2016): 437–452.doi:10.1080/09592296.2016.1196065

- Carlton, David.Churchill and the Soviet Union(Manchester UP, 2000).

- Deighton, Anne. "Britain and the Cold War, 1945–1955", inThe Cambridge History of the Cold War,eds. Mervyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad, (Cambridge UP, 2010) Vol. 1. pp 112–32.

- Deighton Anne. "The 'Frozen Front': The Labour Government, the Division of Germany and the Origins of the Cold War, 1945–1947,"International Affairs65, 1987: 449–465.in JSTOR

- Deighton, Anne.The Impossible Peace: Britain, the Division of Germany and the Origins of the Cold War(1990)

- Feis, Herbert.Churchill Roosevelt Stalin The War They Waged and the Peace They Sought A Diplomatic History of World War II(1957)online free to borrow

- Gorodetsky, Gabriel, ed.Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–1991: A Retrospective(2014).

- Hennessy, Peter.The Secret State: Whitehall and the Cold War(Penguin, 2002).

- Haslam, Jonathan.Russia's Cold War: From the October Revolution to the Fall of the Wall(Yale UP, 2011)

- Hughes, Geraint.Harold Wilson's Cold War: The Labour Government and East–West Politics, 1964–1970(Boydell Press, 2009).

- Jackson, Ian.The Economic Cold War: America, Britain and East–West Trade, 1948–63(Palgrave, 2001).

- Keeble, Curtis.Britain, the Soviet Union, and Russia(2nd ed. Macmillan, 2000).

- Kulski, Wladyslaw W. (1959).Peaceful Coexistence: An Analysis of Soviet Foreign Policy.Chicago: Henry Regnery Company.

- Lerner, Warren. "The Historical Origins of the Soviet Doctrine of Peaceful Coexistence."Law & Contemporary Problems29 (1964): 865+online.

- Lipson, Leon. "Peaceful coexistence."Law and Contemporary Problems29.4 (1964): 871–881.online

- McNeill, William Hardy.America, Britain, & Russia: Their Co-Operation and Conflict, 1941–1946(1953)

- Marantz, Paul. "Prelude to détente: doctrinal change under Khrushchev."International Studies Quarterly19.4 (1975): 501–528.

- Miner, Steven Merritt.Between Churchill and Stalin: The Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the Origins of the Grand Alliance(1988)online

- Neilson, KeithBritain, Soviet Russia and the Collapse of the Versailles Order, 1919–1939(2006).

- Newman, Kitty.Macmillan, Khrushchev and the Berlin Crisis, 1958–1960(Routledge, 2007).

- Pravda, Alex, and Peter J. S. Duncan, eds.Soviet British Relations since the 1970s(Cambridge UP, 1990).

- Reynolds, David, et al.Allies at War: The Soviet, American, and British Experience, 1939–1945(1994).

- Sainsbury, Keith.Turning Point: Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill & Chiang-Kai-Shek, 1943: The Moscow, Cairo & Tehran Conferences(1985) 373pp.

- Samra, Chattar Singh.India and Anglo-Soviet Relations (1917-1947)(Asia Publishing House, 1959).

- Shaw, Louise Grace.The British Political Elite and the Soviet Union, 1937–1939(2003)online

- Swann, Peter William. "British attitudes towards the Soviet Union, 1951-1956" (PhD. Diss. University of Glasgow, 1994)online

- Ullman, Richard H.Anglo-Soviet Relations, 1917–1921(3 vol 1972), highly detailed.

- Густерин П. В.Советско-британские отношения между мировыми войнами. — Саарбрюккен: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing. 2014.ISBN978-3-659-55735-4.

Primary sources[edit]

- Stalin's Correspondence with Churchill, Attlee, Roosevelt And Truman 1941-45(1958)online

- Dixon, Simon (1998).Britain and Russia in the Age of Peter the Great: Historical Documents(PDF).London: School of Slavonic and East European Studies.ISBN9780903425612.

- Maisky, Ivan.The Maisky Diaries: The Wartime Revelations of Stalin's Ambassador in Londonedited byGabriel Gorodetsky,(Yale UP, 2016); highly revealing commentary 1932-43; abridged from 3 volume Yale edition;online review

- Watt, D.C. (ed.)British Documents on Foreign Affairs, Part II, Series A: The Soviet Union, 1917–1939vol. XV (University Publications of America, 1986).

- Wiener, Joel H. ed.Great Britain: Foreign Policy and the Span of Empire, 1689–1971: A Documentary History(4 vol 1972)